“The Zero Ruled the Skies — Until a U.S. Pilot Cracked Its Secret with Matchsticks”

For the first brutal months of the Pacific War, the Japanese Zero wasn’t just an airplane — it was a nightmare with wings.

American pilots watched their friends vanish in streaks of smoke over endless blue water, cut down by an enemy fighter that seemed to break every rule of physics they’d been taught. The Mitsubishi A6M Zero could out-climb, out-turn, and out-range anything the U.S. Navy had. The F4F Wildcat — the mainstay of American carrier aviation — was slower, clumsier, and outclassed in almost every measurable way.

To many pilots, the math was simple and fatal: if a Zero got on your tail in a turning fight, you died.

But one man refused to accept that equation.

Lieutenant Commander John “Jimmy” Thach wasn’t the flashiest stick in the Navy, nor its most decorated ace. What set him apart wasn’t raw flying talent — it was his mind. Analytical. Relentless. Unwilling to let “impossible” be the final word.

In September 1941, three months before Pearl Harbor, an intelligence report landed on his desk at Naval Air Station San Diego. It was stamped for commanding officers’ eyes only. Inside were the cold, clinical numbers that explained why pilots would soon start dying in droves.

The Zero could climb faster than any American fighter. It boasted a 330 mph speed and a combat range that embarrassed the Wildcat. Its turning radius was so tight it might as well have come out of a science fiction serial, not an engineering lab. Line by line, the report said the same thing: the Zero could do everything the Wildcat could do — only better.

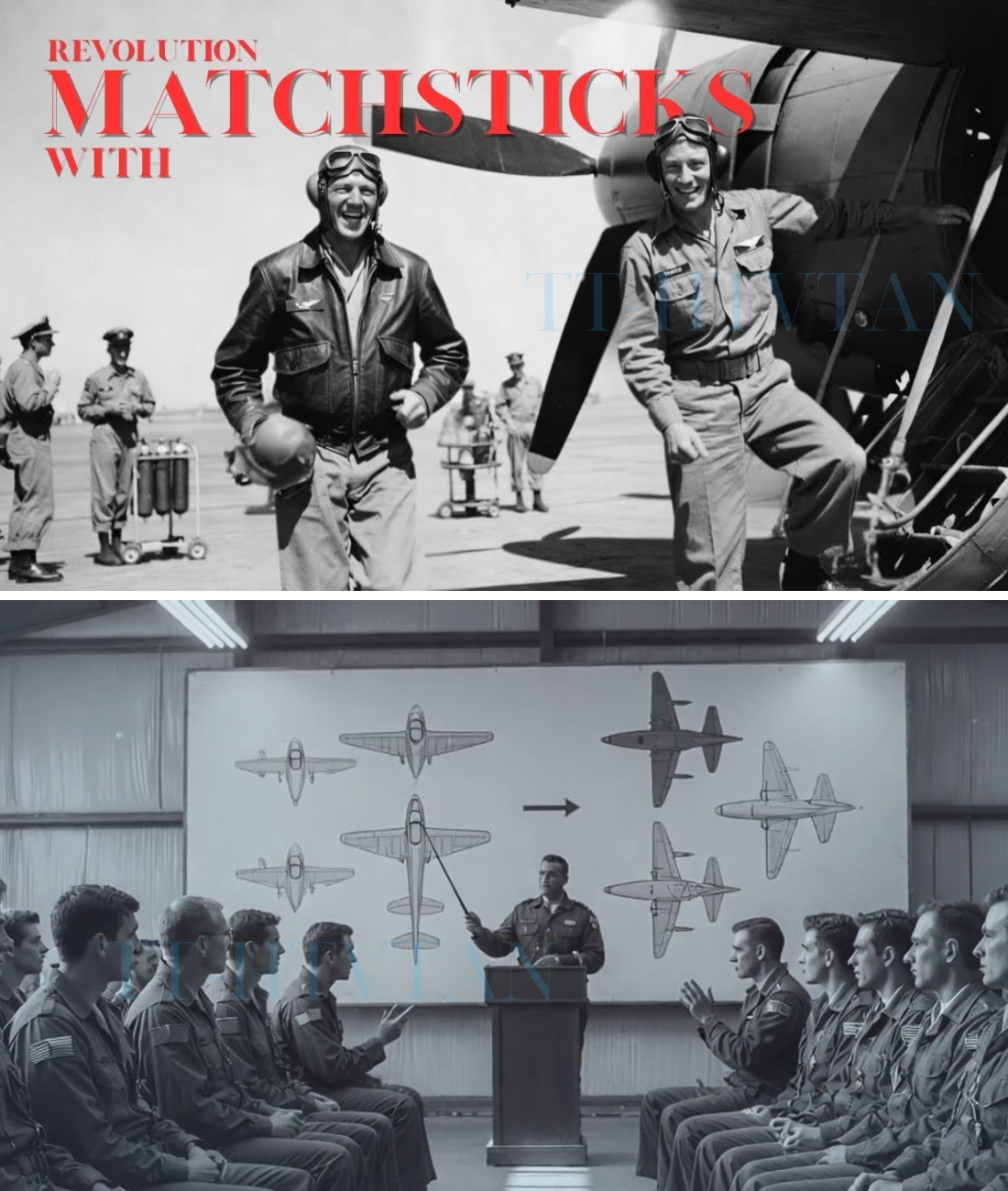

Traditional air combat doctrine was built on one core assumption: that fighters were roughly comparable. Tactics like the defensive circle or one-on-one turning engagements only made sense if both sides were playing with similar tools. Now that assumption was shattered. The Zero wasn’t just better — it rewrote the balance of power in the sky.

Thach understood the implications immediately. If American pilots tried to fight Zeros the “normal” way, they would die. A lot of them.

That night, he carried the report home to his modest house in Coronado, not far from where Navy planes traced white scars across the Pacific sky. He kissed his wife, tucked his daughter into bed, and then did something that would quietly change the course of the war.

He took out a box of wooden matchsticks.

On his kitchen table, each matchstick became an airplane. Two sticks placed side by side became a formation. A third, slid in from behind, became an attacking Zero. Where other men might have gone to sleep and prayed for better planes, Thach went to work.

Hour after hour, night after night, he pushed those matchsticks across the wooden surface, simulating attacks and counterattacks. He tried tight groups and wide spreads, circles and lines, old World War I maneuvers and improvised ideas no manual had ever described. Every solution failed. If the fighters flew too close, a Zero could carve them up one by one. Too far, and they were isolated and doomed.

He wasn’t trying to design a faster engine or a stronger airframe. That was the job of factories and engineers and years of development. Thach was trying to do something more urgent and more fragile: invent a tactic that could turn an inferior machine into a deadly weapon through nothing but teamwork and geometry.

Somewhere in those late hours, after countless failed patterns, the breakthrough came.

Thach placed two matchsticks parallel to each other, separated by the distance he calculated as roughly equal to the Wildcat’s turning radius — about 1,500 feet. Then he brought in a third stick from behind, representing a Zero slipping onto the tail of one of the Wildcats.

This time, instead of the targeted stick breaking away alone, both defenders turned toward each other at the same moment. Their paths crossed like the blades of a pair of scissors. The attacking Zero, glued to one Wildcat’s tail, suddenly found another Wildcat flying straight at it, guns aligned.

In that instant, the problem flipped.

If the Zero continued its attack, it would fly head-on into the sights of the second Wildcat. If it broke off to avoid being shot, it lost its advantage. And if it switched targets and tried to chase the other Wildcat instead, the maneuver simply repeated — the two defenders crossing, weaving, constantly turning the hunter into the hunted.

On the table, the pattern was elegant. If two pilots could fly it with perfect timing, they could turn a Zero’s greatest strength — its phenomenal turning ability — into a liability. The maneuver would later be called the Thach Weave.

But matchsticks can’t shoot back. Real airplanes do.

In early 1942, with the Pacific already burning, Thach took his idea into the sky. Over San Diego, he had his pilots form up according to his new “beam defense” concept and recruited one of the most aggressive and skilled aviators he knew to play the attacker: Ensign Butch O’Hare, who would later become the Navy’s first ace of the Pacific and a Medal of Honor recipient.

At 15,000 feet, O’Hare came barreling in at the formation, trying every trick he knew to crack it. High-side attacks from above. Slashing dives from below. Angled approaches designed to sneak around their defenses.

Every time, the same thing happened.

As soon as he slid onto one Wildcat’s tail, the targeted pilot turned toward his wingman. The wingman turned toward him. The formation crossed — and O’Hare suddenly found himself staring down the nose of another fighter, pointed straight at his cockpit.

After twenty minutes of frustration, the mock battle ended. On the ground, O’Hare wasted no time.

“Skipper, it really worked,” he told Thach. “I couldn’t make a single attack without seeing the nose of your airplane pointed at me. I don’t know how to get through it.”

The theory had survived its first trial by fire. The next test would be real bullets, real deaths — and a real enemy.

That test came on June 4, 1942: the Battle of Midway.

Thach led six Wildcats as escort for twelve slow, vulnerable TBD Devastator torpedo bombers. When they found the Japanese carrier force, the sky exploded into chaos. Zeros swarmed the formation, diving in with ruthless precision. Within minutes, ten of the twelve Devastators were burning wrecks on the ocean’s surface.

Thach’s tiny escort group was now outnumbered roughly four to one.

One Wildcat went down almost immediately. With five fighters left and Zero tracers stitching the air around them, Thach called his wingmen into the weave.

What happened next looked, from a distance, like a dance written by desperation.

When a Zero latched onto Ensign Robert Dibb’s tail, he called out and turned toward Thach. Thach turned toward him. The two Wildcats crossed — and Thach fired a burst straight into the Zero’s belly as it flashed overhead. The Japanese fighter burst into flames and tumbled into the sea.

Another Zero tried a head-on attack. Thach held his nerve, waited until the last possible instant, and then squeezed the trigger. The Zero’s engine cowling disintegrated, and the aircraft spiraled away, trailing fire.

A third Zero tried to exploit the Wildcat’s known weakness in a tight turn, chasing Dibb through a hard bank — only to fly straight into Thach’s guns as the weave brought him into position behind it.

In less than ten minutes of savage combat, Thach shot down three Zeros. Dibb downed one more. Outnumbered, out-climbed, and out-turned, the Wildcats survived. The Zero, for the first time, had been beaten not by a better machine — but by better thinking.

Word of Thach’s tactic spread through the fleet like electricity. Fighter squadrons adopted it. Marine pilots on Guadalcanal used it daily against swarms of Zeros from Rabaul. Japanese ace Saburo Sakai would later write with frustration about these new American “double-team” maneuvers that forced his pilots to break off attacks and dive for safety from aircraft they’d once considered easy prey.

By late 1942, the Thach Weave was standard doctrine.

It didn’t magically turn the Wildcat into a superior airplane. It did something subtler — and more powerful. It rewrote the geometry of the fight. No longer was the typical engagement one Zero against one Wildcat. The weave made it two-against-one, every time, with the Americans fighting as a coordinated unit instead of isolated individuals.

Even after newer, deadlier fighters like the F6F Hellcat and F4U Corsair entered the war, the weave endured. The U.S. Army Air Forces applied its principles to P-38s and P-40s. Later generations of jet pilots flying F-4 Phantoms over Vietnam would still train on tactics descended from Thach’s kitchen-table experiment. The core principle never changed:

Two pilots working together are more lethal — and more survivable — than two pilots fighting alone.

John Thach went on to become a full admiral, shaping not just fighter tactics but anti-submarine warfare and broader naval strategy. A Time magazine cover. A Navy frigate bearing his name. Awards and honors that stretched far beyond the Pacific.

Yet his greatest legacy isn’t a ship or a medal. It’s an idea.

One man, a kitchen table, and a box of matchsticks — refusing to accept that his pilots were doomed. Refusing to surrender to the supposed inevitability of superior enemy technology. Choosing, instead, to think harder.

The Thach Weave is a reminder that in war, as in life, you don’t always get to choose your equipment. What you do control is how you use it. Tactics, training, and creativity can turn inferiority into advantage. Sometimes the difference between survival and disaster is the willingness to stay up a few extra nights, move the “matchsticks” on your own table, and ask:

Is there another way to fight this?

News

He Left Me for His Mistress – Then I Dropped the DNA Test on the Table

“Email,” I whispered. I opened the file alone at my desk.The alleged father is excluded as the biological father…

I Came Home for Thanksgiving and Found My Husband Gone — Left Alone With His Stepfather

He showed me medical reports, insurance letters, even canceled appointments.They had abandoned him long before the cruise; they’d just made…

I Canceled My Mother-in-Law’s Birthday Dinner After They Excluded Me – Revenge Was Sweet

The Exclusion The first dinner was at a little trattoria in Trastevere—a charming place I’d chosen for its warmth…

Dad Said “You’re Too Emotional to Lead!” and Fired Me—Six Months Later He Begged, “Please Help!”

Part 2 — The Collapse You know that strange silence after a storm, when everything feels too still…

“It’s Just a Chair, You Can Stand!” Dad Mocked—I Smiled and Said, “It’s Just an Eviction Notice”

Silence When I got home, I didn’t turn on the lights. The apartment was quiet, still smelling faintly of…

Sis Banned Me From the $30 K Wedding I Paid For — “You’re a Security Risk!”

I hung up and stared at the vineyard through the windshield. The music was swelling. Guests were seated. The fairy…

End of content

No more pages to load