The difference between being dismissed and being erased is paper thin. I learned that watching my seven-year-old daughter, Emma, bend in her new yellow dress to pick up candy wrappers while the Henderson twins shrieked with their kazoos and flung water balloons, gift bags abandoned like trophies on the lawn.

My parents’ fortieth anniversary party was supposed to be a celebration of family. Mom had planned it with military precision: white string lights strung across the big maple, rented round tables clothed in cream, a three-tier cake from that bakery downtown that charges per flourish. For two months she’d called me every Wednesday—table runners, hydrangeas, a discussion about whether a grazing board counts as an appetizer or a statement piece.

We arrived early because she’d asked me to help with the dessert table. Emma wore the yellow dress I’d picked out just for today, hair tied back with satin ribbons, fingers curled around a gift she’d wrapped herself: a crystal picture frame she’d saved allowance to buy. “To Grandma and Grandpa, happy anniversary. Love, Emma.” She’d practiced the letters until “Grandma” didn’t tilt too far to the right.

Vanessa—my sister—was already there, snapping orders at the catering staff with the casual authority only people born first seem to inherit. She’s Mom’s favorite: the successful one with the surgeon husband, the private-school kid, the Boston address. I am the one who divorced at twenty-nine, the paralegal instead of the lawyer, the daughter who rents a two-bedroom with mismatched plates and a coffee table that used to be a trunk.

By four o’clock, the backyard was full: neighbors, Dad’s firm, Mom’s book club ladies, golfers who smelled faintly of cologne and sunscreen. Kids ran like they’d been released from fluorescent classrooms into some promised land. Emma stood at the fringes, watching the velocity of other children, testing the edges before stepping in.

After speeches and cake, Mom emerged with a stack of glossy white bags stuffed with tissue and ribbon. “Something special for the children,” she’d said on one of our Wednesday calls. The swarm formed immediately. “Madison, sweetie—here you go. Brandon, yours. Ashley, don’t forget!” The Henderson boys fist-pumped. The Patel twins squealed. Tyler—Vanessa’s—didn’t look up from his iPad as a bag landed in his lap.

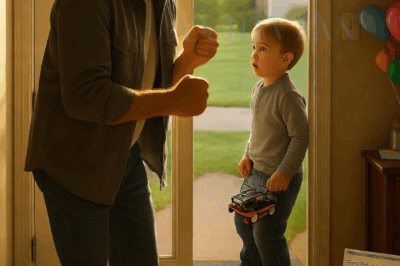

Emma stepped forward with an open palm and a small hopeful smile.

Mom’s hand shot out to Emma’s shoulder. “Wait your turn,” she said, pushing her back without a glance, smiling at Mrs. Henderson.

Emma did what she has been taught to do: she waited. The crowd thinned. Tissue paper fluttered like white birds across grass. The last bag went to the neighbor’s niece, a child I’d never met.

Emma took a breath and tried again, softer this time. “Grandma, can I have one?”

Mom was laughing at something Mrs. Henderson said about cruises. She didn’t turn. Vanessa appeared as if summoned and pressed an empty bag—the kind guests had dropped after tearing into their prizes—into Emma’s hands. “Here,” she said, voice syrupy and sharp. “Pick up the trash.”

Tyler looked up and snorted. “Yeah, clean up.” The twins giggled. A half-circle formed effortlessly, the way kids assemble around cruelty as if it’s a campfire.

Emma looked down at the empty bag, then up at Vanessa, then at me. Confusion washed across her face and tried to fade into composure the way she’s seen me do a thousand times.

Something hot and serrated twisted under my ribs. I walked to Mom, who was now talking about the Mitchells’ cruise cabin upgrade, and said in a voice I didn’t recognize, low and even, “She’s your blood.”

Mom turned, smile intact, eyes cool and flat. “If you don’t like it,” she said, “don’t come next year.” A beat. “And before you leave, clean the whole area.”

The Mitchells shifted, embarrassed for the wrong person. Mom pivoted back to her conversation. A string of lights clicked on overhead; everybody glowed except us.

I stood in that space where a daughter ends and a mother begins. Then I went to Emma. She was on one knee now, careful not to wrinkle the dress, collecting wrappers into the bag like they were something delicate. Her face was arranged, the way children arrange themselves to not make trouble.

“Come on, baby,” I said. “We’re leaving.”

She looked at the gift box in her hands. “But I didn’t give them their present.”

“We’ll mail it.”

“Are you sure?” A tiny crease between her brows.

“I’m sure.”

We walked through the gate. Behind us, the party swelled over our absence without a ripple. No one called our names. I held the gate an extra second so it wouldn’t slam and give anyone the pleasure of thinking we’d made a scene.

In the car, Emma watched her lap. “Did I do something wrong?”

“No, sweetheart. You did nothing wrong.”

“Then why…?”

“Some people are mean,” I said. “Even people who should know better.”

She was quiet for half a block. “I still want them to have the present.”

I looked at her in the rearview mirror—at a child protecting a gift for people who just made her pick up garbage. Grace in a seven-year-old body. “We’ll make sure it finds its way,” I said.

That night she brushed her teeth without me asking and chose the unicorn pajamas. “Mom?”

“Yeah, baby.”

“Next time can we just stay home? Just us?”

My throat tightened in that place grief and relief occupy together. “Yeah,” I said. “We can do that.”

She fell asleep in three minutes, cheeks flushed, the day folded and tucked away for later.

I sat at the kitchen table with chamomile tea gone cold, and I didn’t feel rage. Rage would have been simpler. What I felt was colder and clearer—the point at which an old story ends. For years, I’d let my parents rank their daughters like test scores: Vanessa’s accomplishments were banners; mine were footnotes. Each Christmas, Vanessa got a check and a photo-op; I got dish towels with a pattern Mom called “tasteful.” I tolerated it because swallowing glass is easier when it only cuts you.

They’d crossed into cutting my child.

I called Rachel, my best friend, the one who kept me upright during the divorce and texts me memes during budget season. “How was the party?” she asked, which opened my mouth. I told her everything. I held myself together until I described Emma kneeling in her yellow dress, and then I didn’t.

“I’m coming over,” Rachel said.

“You don’t have to.”

“I’m already in the car.”

She arrived with a bottle of wine and a look that lives somewhere between murder and mercy. We sat at my table while Emma slept and I plotted—badly and then better. Rachel works in real estate law; I work in litigation support. Between us, we know more about municipal code, permits, licensing, and property records than most people ever want to. “You’re not going to slash tires,” she said. “You’re going to speak fluent bureaucracy.”

We talked until midnight. At some point, it stopped being revenge and started being a lesson plan for Emma: what boundaries look like in practice, what consequences look like when they’re not screamed but filed.

The next morning, I woke to sunlight and a small weight climbing into my lap. “You okay?” I asked.

She nodded against me, then tried for words. “I feel like…” She made a face. “Like I’m not good enough.”

“Emma.” I lifted her chin. “You are more than good enough. What happened yesterday wasn’t about you. It was about them forgetting how to be decent.”

She considered this like she considers math. “Are we going to see them again?”

“Not for a while,” I said. “Maybe not.”

She nodded. “Can we get pancakes?”

“Of course we can.” Children’s superpower is how they leap toward joy from the ugliest edges. At IHOP she wore whipped cream on her nose like war paint and laughed until she hiccuped, and I took a photo—happy, sticky, seven.

That afternoon, while she watched cartoons, I opened my laptop. The law is a set of rules; power is knowing which drawer they live in. My parents live in a neighborhood where HOAs have bylaws thick as hymnals and the city posts inspection calendars online. Over the years, Dad had built a shed a shade too large, raised a fence a shade too tall, and poured a driveway a shade too wide. Mom runs a very successful “hobby” making custom invitations—no license displayed; the Etsy page brags about two hundred orders. None of it is a scandal; all of it is… out of bounds.

I didn’t break into anything or invent anything. I read. I measured. I checked public records. I documented. Not because I wanted to burn their house down, but because I wanted Emma to watch me do something clean: to see that consequences aren’t tantrums, they’re processes.

I submitted what needed submitting, where it needed to go. I clicked “anonymous” because I was not going to turn this into a family spectacle, and because the spectacle already happened in a backyard under string lights. Then I closed the laptop and made grilled cheese.

That evening, instead of tinkering with complaint numbers, I pulled a bag of chocolate chips from the pantry. “Cookies?” I called.

Emma appeared like a prairie dog. “Cookies?”

We made the world’s messiest batch. I cracked an egg onto the counter instead of into the bowl. “Maybe the counter needed some protein,” I said.

“Counters can’t be sad,” she said, exasperated and delighted.

“How do you know?”

She threw a dusting of flour at me. I chased her around the island while she shrieked. The cookies burned slightly on the bottom and still tasted like everything right. We watched a penguin documentary. She fell asleep against my arm with chocolate on her cheek. This—this—was the point.

In the morning, I placed Emma’s gift—the crystal picture frame, still wrapped in silver—on my parents’ doorstep. Next to it, I set the empty gift bag Vanessa had shoved at Emma. I’d written three words on a note and tucked it inside: “For everyone who mattered.”

At 7:12 a.m., as I buckled Emma into the car for school, my phone lit with a text from Rachel: Did you hear it? I hadn’t, but I could imagine. The sound of realization can be loud.

The week unspooled. Emma’s teacher called to say she’d been quieter than usual. “She’s processing,” Mrs. Kovalski said. “We’ll loop in the counselor if it doesn’t lift.” That night we made mac and cheese and built a fort with every blanket we own. When we crawled inside, she handed me a crayon drawing: me and her and our apartment with a crooked sun, and the words, “Home is where mom is.” I held it like a relic.

Thursday, a bright orange notice appeared on my parents’ door—the kind neighbors notice with a particular satisfaction specific to covenant-heavy streets. Friday brought a letter from the HOA. The following Monday, Dad texted: Can we talk? I let it sit. Two hours later, Mom called. “This is ridiculous,” she said. “Your father is beside himself. Do you know what it costs to—”

“Mom,” I said. “You pushed your granddaughter aside at your own party.”

“That is not—”

“And told her mother to clean up on the way out.”

Silence, the kind that isn’t empty. “We were overwhelmed,” she said finally, as if that explained physics, hunger, history.

“Emma was seven,” I said, and hung up because some sentences don’t deserve answers.

Vanessa tried next. “Someone made a fake LinkedIn with my picture.”

“I hope they picked a flattering one,” I said.

“Don’t be petty, Emily. You left the party in a huff and—”

“Oh,” I said softly, “you mean when your son laughed while my child picked up wrappers? That party?”

Silence again, then a dig for ground that isn’t there. “You’re overreacting.”

“Maybe,” I said. “But I’m done underreacting.”

Eventually, Dad showed up at my apartment. He looked older, the way men look when the stories they’ve told themselves don’t quite hold. “We know it was you,” he said, standing in my doorway with hands that have signed checks and forms and dotted line after line.

“I don’t confirm or deny anonymous gossip,” I said, stepping aside.

He sat. “It has to stop. We’re drowning—fines, letters, inspections—your mother hasn’t slept—”

“Where were you,” I asked, “when Emma asked for a gift bag?”

He flinched. “Your mother—”

“Don’t,” I said. “Don’t tell me she didn’t mean it. She meant it enough to say it out loud. One mistake is a slip. This is a pattern you call tradition.”

He rubbed his eyes. “Do you want an apology? Fine. I’m sorry. Your mother is sorry. Vanessa is sorry. We’re all sorry. Please, Emily.”

“Say you’re sorry to Emma,” I said. “And then prove it for the rest of her life.”

He swallowed. “Will you… come to dinner?”

“No,” I said. “We’re building something else.”

After he left, I did something that surprised even me: I unclenched. I didn’t need to micromanage the rest. Whatever I’d set in motion would run its civic course—letters, corrections, fees. Not a bonfire. A ledger.

I stopped answering Mom’s calls. When a card addressed to Emma arrived with a fifty-dollar bill inside, I mailed it back with Emma’s picture frame and a copy of her handwritten card. I included a note in my handwriting this time: The only gift that matters is how you treat her.

Weeks passed. Emma got louder in class again, then volunteered to be line leader. She learned to draw horses with improbable eyelashes and told me facts about penguins that were somehow both adorable and bleak. She joined a soccer team where everyone forgot which goal was theirs at least once. After her first successful steal, she ran to the sideline beaming. “Did you see? I helped!”

“You did,” I said. “You really did.”

We built new traditions: Saturday pancakes with mountains of whipped cream, Sunday matinees with contraband gummy bears, Tuesday night library runs where she checks out more books than her backpack should allow. We invited Mrs. Chen from downstairs for tea and heard stories about a city half a world away that tastes like lychee and train metal.

In November, an embossed invitation arrived: Thanksgiving, 847 Maple, “We hope to see you there.” Emma found it in the recycling. “Is that from Grandma?”

“Yes.”

“Do you want to go?” I asked.

She thought in that careful way she has, like she’s rolling a marble along a maze. “Not really,” she said. “Can we do our own? We can invite Mrs. Chen. And maybe Marcus?” (Marcus is a gentle man I dated briefly who never talks down to children and returns library books on time. We are friends now; it’s enough.)

“We can invite whoever we want.”

We made a menu on printer paper. Emma drew a turkey that looks like a hand because all turkeys look like hands when you’re seven. On Thanksgiving, our small apartment filled with the smell of rosemary and butter and the particular kind of laughter that happens when no one is guarding their worth. Mrs. Chen brought a cherry pie. Marcus brought rolls that rose like small suns. Emma made place cards in glitter and got glitter everywhere and didn’t pick it up because no one asked her to.

My phone buzzed during dishes: You didn’t come. I made your favorite pie. I powered it off. The pie my mother made could not fix the mouth that told a child to pick up trash.

Emma leaned against me on the couch, eyes fluttering heavy. “Best Thanksgiving ever,” she murmured.

“Yeah,” I said. “It really was.”

Outside, the city threaded itself with light. Somewhere across town, my parents were probably loading a dishwasher and adding up fines and wondering what on earth had happened to loyalty. Somewhere, Vanessa was composing a caption about gratitude that would rack up hearts from people who don’t know how sharp words can be when they’re whispered behind perfect teeth. Here, in a room with an oil-splattered stove and a lopsided paper turkey on the fridge, my daughter fell asleep sure of one thing: home is where she is wanted.

I started this wanting them to hurt like she hurt. The secret I uncovered in the process was simpler and truer: the best revenge is refusing to audition for a role that always demanded less of me than I am. The best revenge is building a life where my daughter never has to earn the right to be treated well. Let them keep their house with its letters taped to the door. Let them keep their careful invitations and careful excuses. We will keep the laughter that doesn’t require permission.

They handed Emma an empty bag and told her to pick up trash.

I handed her a full life and told her to keep what is hers.

News

The Empty Chair That Speaks Louder Than Words: Erika Kirk’s Emotional Tribute to Charlie

At a recent gathering that was meant to be filled with unity, purpose, and vision for the future, one symbol…

Boys Laughed at New Girl Eating Fries Alone — 30 Seconds Later, They Were Taken Down in Front of the Cafeteria

It was the kind of winter night that tests the marrow of a man. Snow fell in suffocating sheets, a…

Boy Wouldn’t Stop Kicking His Seat—Watch How He Ended That!

James Parker had been looking forward to this flight for weeks. After a brutal schedule of back-to-back meetings in New…

My Dad Said, “We’re Skipping Your Kid’s Birthday—Money’s Tight.” I Believed Him. Then I Saw His…

I still remember the knock. Heavy. Desperate. My father’s fist on my door at nine in the morning, pounding until…

AT MY HUSBAND’S SISTER’S ENGAGEMENT, THE TAG ON MY CHEST READ “HOUSEKEEPER”

The paper tag clung to my chest like a cruel joke. Black letters, bold and simple: HOUSEKEEPER. Around me, laughter…

PART 2: My Parents Kicked Me Out in 11th Grade for Being Pregnant — 22 Years Later They Sued Me…

Ten Years Later The Texas sun was setting, bathing the Austin skyline in hues of gold and crimson. Chelsea Norton…

End of content

No more pages to load