“They’ll Auction My Children Next Week,” Wept the Widow — The Lonely Rancher Took Them In

The knock came sharp, not hesitant, but desperate. The sound of someone who knew they had no other door left to try. Thomas Avery, the rancher folks in town called the loneliest man on the prairie, had just finished banking the fire when it came.

He opened the door with a furrowed brow, expecting maybe a traveler, maybe trouble, but not what stood there in the dimming light. A woman, shoulders sagged beneath a tattered shawl, clutched three children so tightly to her sides it looked as though she feared the wind itself might steal them away. Her face bore the hollowess of hunger, the raw redness of tears shed too long.

And when her lips parted, her voice cracked like brittle timber. “They’ll auction my three children next week,” she whispered, and her knees gave out. The youngest girl let out a frightened cry while the boy beside her tried to steady his mother with a grip far too small for such a burden. Thomas dropped to his hunches before the woman hit the dirt, catching her by the shoulders.

He could feel how light she was, as if the storm of grief had stripped her body of flesh and left only bone, skin, and sorrow. He looked at her face and then to the children, the boy, maybe 12, jaw clenched against fear. The girl, nine at most, clinging to her mother’s shawl. The little one barely five, trembling so hard her teeth chattered.

The woman’s name came out in broken gasps. Mary. Mary Dalton. Thomas had never seen her before, but he knew that name. The Daltons had lived two valleys over before fire and sickness cut through their homestead. Rumors spread, as they always did, but no rumor had spoken of this, of a widow with nothing left but her children being driven to desperation.

Inside, Thomas said, his voice low, steady, but urgent, he helped her up and ushered them past the threshold, his callous hands careful not to frighten the little ones. The door closed against the night, shutting out the cold wind. But inside the cabin, another storm began to gather. Mary collapsed onto the chair nearest the hearth, her children clustering around her like frightened birds.

She clutched them close as though any space between their bodies might open the way for them to be snatched from her arms. Her chest heaved, her lips moved in frantic prayer, though no words came loud enough to catch. Thomas crouched down before her, his steady gaze meeting hers. “What do you mean auction?” Mary’s eyes brimmed again, spilling down cheeks already raw from salt and wind.

The town debt collector, he said, “I owe what I can’t pay. The land is gone. The house burned. They say the only thing of value left are my children.” Her voice broke and the words trembled into the quiet like a curse too wicked to be spoken. He told me they’ll be sold at the block one by one next week. The children froze at her words.

The boy’s fists balled, his jaw trembling despite the way he bit it tight. The girl buried her face in her mother’s sleeve, muffling her sobs. The youngest simply stared, wideeyed and uncomprehending, though her tiny hand clutched her mother’s wrist with bruising desperation. Thomas felt a heaviness pressed down on him. He had lived alone for years, ever since loss had hollowed his own house.

He had thought solitude was the safest way to walk through life. No ties, no weight, no heart left exposed. But now, staring at these children and their broken mother, he realized safety was a poor word for such silence. Mary spoke again, and her words cut him deeper than the cold ever had. Please, if you turn me away, I have nowhere else to go. They’ll take them.

Her plea was not dramatic. It was raw, stripped to the truth. Thomas drew in a slow breath, the air heavy with the smoke of the fire. He looked to the children, then back to Mary, and he knew this was not a decision that left room for hesitation. You won’t face that alone, he said at last.

The room seemed to still at his words, but outside the wind rattled the cabin walls as if warning them of what was to come. Thomas did not know what awaited them at the end of the week. He did not know who would rise against them, or how steep the cost of defiance would be. But he knew one thing as clear as he knew the crackle of fire in the hearth.

Mary Dalton and her children would not be put on an auction block so long as he drew breath. The children looked up at him, eyes wide, uncertain whether to believe. Mary pressed her forehead to her hands, tears slipping freely now. And Thomas, the loneliest man on the prairie, felt the first weight of a burden he had not asked for, but one he would carry come what may.

And in that cabin, with the storm whispering at the eaves, the lines of their fates tangled together, mother, children, and lonely rancher bound by a single promise. The fire burned low, its crackle filling the silence after Mary’s sobs had quieted into broken breaths. Thomas sat across from her at the rough huneed table, his fingers drumming once against the wood before curling into a fist.

He wasn’t a man who spoke much, nor one who wasted words when they came. He preferred the company of work of cattle, of the wind moaning through the pines. Yet now silence felt like a cruelty. Mary sat stiff in the chair, her shawl still clutched tightly around her shoulders as though it were armor. The children pressed close, Samuel, the oldest, his jaw squared against fear.

Ruth, smaller, still hiding her face in the fabric, and little Clara fighting sleep though her head sagged against her mother’s arm. Thomas could see the exhaustion in their frames, the kind that seeped into bones and hollowed the spirit. You’ve walked far, he said at last, his voice gravel.

Mary lifted her eyes to him, shadowed and red from tears. Since the fire. Since since I had no place else to go. She swallowed hard, forcing the next words out like stones. The collector said he’d send word to the sheriff that the sale would happen in cold river. Her lips trembled. I can’t let them. I won’t let them.

Continue in the c0mment

Thomas leaned back, the chair creaking beneath his weight. He had heard enough of Cold River’s dealings to know the truth in her words. Debt collectors there ran their own kind of law, often sharper than any badge. A family’s ruin was profit for men who never lifted a plow or drove a herd. He pictured Samuel forced into labor.

Ruth handed off like property. Clara crying herself horse in a stranger’s arms. His jaw clenched so tight it achd. Cold River won’t have them,” Thomas said finally, his voice like iron dragged over stone. Mary’s breath hitched. She looked at him as if she scarcely dared to believe. “But how? You don’t know them. You don’t know me.

Why would you risk?” she trailed off, staring down at her children as if the thought itself was too large to finish. Thomas stared at the flames a long moment before answering. because I know what it’s like to lose a family, and I’ll be damned before I let that happen to yours while I’m standing here.” Samuel straightened at those words, eyes flickering with something fierce and unspoken.

Ruth’s sobbs quieted into small hiccups, though she didn’t lift her face. Clara, too young to understand, nestled deeper against Mary’s side, her tiny hand slipping into her mother s. For the first time since she had crossed his threshold, Mary let herself breathe. Not easy, not free, but enough to ease her shoulders from their rigid hunch. Tears welled again, but this time they carried a glimmer of something fragile, hope.

By morning, the ranch wore its usual stillness. But within the cabin, something had shifted. Mary rose early, her hair pulled back, her hands moving with quiet purpose as she set about tidying dishes and sweeping ash from the hearth. She moved as one determined to repay hospitality, though Thomas suspected it was more than that.

It was survival, a need to keep her hands busy lest despair take root again. Samuel followed Thomas outside, trailing close as he checked the barn and water troughs. The boy didn’t speak much, but his eyes followed every motion. When Thomas hefted a pitchfork, Samuel mimicked, though the handle was too heavy for him. “Thomas said nothing, only shifted a smaller tool into the boy’s hands.

Samuel’s grip tightened like he had been handed a weapon. “You ever work cattle?” Thomas asked, voice low. P taught me some,” Samuel answered, his voice rough but steady. “Before Before he took sick.” Thomas nodded. Then you know what it means to pull your weight. You keep that, you’ll do fine here.

The boy’s chest swelled faintly with pride, though he hid it quickly. Thomas saw it anyway. Inside, Mary watched from the doorway, her heart pulled taut between gratitude and worry. She wasn’t used to kindness that asked nothing in return. It frightened her almost as much as the cruelty she’d fled. What if he changed his mind? What if he sent them away? She clutched Clara closer, whispering a prayer beneath her breath. Ruth tugged at her skirt.

Mama, is he really going to stop them from taking us? Mary crouched to meet her daughter’s eyes. He says, “So, child, and I believe him, for now that’s enough.” But even as she spoke, her voice carried the tremor of doubt. Belief was one thing. The men of Cold River were another. That evening, as the sun bled red across the horizon, Thomas returned from mending a fence line with Samuel trudging faithfully behind.

They found Mary seated by the fire, her children dozing in her lap. She looked up, exhaustion plain, yet her eyes held something steadier than the night before. Thomas set his hat on the table and leaned against the wall. You can’t stay hidden here forever. Cold River won’t forget a debt. Mary’s face pald, though she nodded. I know.

I’ve thought of nothing else since he told me. Every hour, every breath, I see their hands reaching for my children. She bit her lip hard, forcing back a sob. Tell me what to do. Thomas folded his arms, his gaze steady. First, you rest. Tomorrow we ride to town. I’ll have words with the sheriff. If Cold River thinks they can take children for coin, they’ll answer to more than a mother’s grief.

Mary’s eyes widened. But no buts, Thomas cut in, though his voice was not unkind. I’ll not let them drag you back in chains of fear. We’ll face them headon. The fire popped, sparks leaping up the chimney. Samuel’s head lifted, his young face set with determination beyond his years.

Ruth shifted in her sleep, her hand tightening on her mother’s dress. Clara whimpered, and Mary hushed her gently, though her own heart thundered. She looked at Thomas Avery, this rancher she’d stumbled upon at the edge of despair, and wondered what had compelled him to risk himself for them.

Loneliness perhaps, or a heart still scarred by his own losses. Whatever the reason, she clung to it, for it was all she had left. That night, Mary lay awake on the pallet Thomas had made for her and the children. She stared at the ceiling beams, the shadows cast by the fire light dancing across the wood. Every time she closed her eyes, she saw the block in cold river, saw her children’s hands wrenched from hers.

But when her gaze shifted to where Thomas sat by the dying fire, shoulders broad, head bowed in thought, she found her breath easing. Not because the danger had vanished, but because someone else carried the weight with her now. And in that fragile space between fear and hope, Mary dared to believe deliverance might yet come.

The next morning dawned cold, frost clinging to the earth. Thomas saddled two horses, his motions practiced and sure. Samuel stood beside him, excitement and nerves battling in his eyes. Mary stepped out, shawl wrapped tight, Clara balanced on her hip, and Ruth clutching her hand. “Are you sure?” she asked, voice trembling. “If they see me, if they see us.” Thomas tightened the cinch strap, his jaw set.

“That’s exactly why we go. Fear only grows in the dark. We’ll drag it into the light.” He mounted, then extended a hand to her. She hesitated, then placed her trembling fingers in his grip. His strength hauled her up before him, Clara between them. Ruth perched before Samuel on the second horse.

As they rode toward town, the chill wind biting their cheeks. Mary whispered a prayer into the morning air. Behind her the land stretched wide and merciless, but before her, for the first time in many long nights, lay a chance, a chance to fight, to hold on, to keep her children from the block. But Cold River was waiting, and its shadows ran deeper than she could yet imagine.

The ride into Cold River carried the tension of a hanging rope. Every hoofbeat another tick of dread hammering through Mary’s chest. She kept her shawl pulled tight against the morning chill, though it did little to fight the trembling that came not from the cold, but from what awaited them.

Claraara whimpered against her shoulder, too young to understand the peril, but sensitive enough to feel her mother’s fear. Ruth rode stiffbacked on the second horse, clinging to Samuel, who sat rigid with determination, though Thomas could see the boy’s jaw quivering when he thought no one looked. The town emerged over the ridge like a scar on the land.

Buildings crouched together, weatherworn boards and paint long faded, but still a bustle stirred there. merchants shouting, wagons rattling, horses snorting as their riders dismounted. And above it all the courthouse stood, not grand, but imposing in its own way, its facade promising law, but wreaking of something fowler, profit wrapped in order. Thomas slowed the horses as they entered the main street.

Men loitered on porches, some tipping their hats in half-hearted greeting, others staring too long at the woman clutching three children like they were shields. Whispers carried soft at first, then sharper. Mary’s name hissed through cracked teeth like gossip made flesh. She lowered her gaze, cheeks burning. Thomas’s jaw tightened.

He kept his gaze forward, shoulders square, daring anyone to step in their path. At the sheriff’s office, he rained in and swung down from the saddle. He offered his hand to Mary, helping her dismount. With Clara still in her arms, Ruth slipped to the ground beside her brother. Thomas knocked once hard on the door.

Sheriff Alden appeared, a thick man with a face like sunbleleached leather and eyes sharp as glass. He leaned against the doorframe, gaze moving over the group with cool disinterest until it landed on Mary. His mouth curled, not in surprise, not in pity, but in a knowing smirk. Well, now he drawled. Mary Dalton thought you’d vanished for good. Seems cold river wasn’t rid of you after all.

Mary flinched. Thomas stepped forward, his frame cutting the sheriff’s view of her. She came to speak on business. Alden raised a brow. Business. The only business she’s got is debt, and the collectors got claim enough to prove it. His gaze shifted back to Mary, his smirk widening.

Word is, he means to settle it next week. I don’t recall you being invited to interfere, Avery. Thomas’s voice hardened. Children aren’t property. You stand by while a man tries to sell them, and you’re no better than the ones holding the block. The sheriff straightened, crossing his arms over his chest. Careful how you speak, rancher. You’ve got no say in Dalton debts.

The law is the law. Mary’s voice burst forth, raw and trembling. Please, these are my children. I’ll work. I’ll serve. Just don’t let them. She clutched Clara tighter, her knees nearly buckling. Ruth reached for her mother’s hand, and Samuel stepped in front of them both as if his small body could ward off the world. The sheriff didn’t move. His eyes slid from the children back to Thomas.

I’d suggest you keep your nose in your own affairs. Cold River’s debts don’t need a lonely rancher’s pity meddling with them. Thomas’s fists curled at his sides. The urge to strike rose sharp and hot, but he knew fists would only tighten Alden’s smug grin. He drew in a slow breath, forcing his voice steady. “Then I’ll speak with the collector myself.

” Alden barked a humorless laugh. You’ll find him at the saloon. But I warn you, Avery. You step into this, you’re stepping into a fight you can’t win. Thomas’s eyes didn’t waver. I’ve already stepped in. He turned, guiding Mary and the children back onto the street.

She staggered under the weight of fear, but his steady hand on her elbow held her upright. Samuel’s eyes blazed. Ruth’s tears threatened to spill, and Clara whimpered in her mother’s arms. The saloon loomed at the far end of the street, its doors swinging wide with the laughter of men who had never known hunger, their voices thick with drink and cruelty. The collector, Henry Lark, was there. Thomas knew it before he stepped through the threshold.

Inside, smoke curled through the air, mingling with the sour stench of whiskey. Men crowded around tables, cards flashing, coins clinking, boots stomping as laughter rose and fell. At the far table sat Henry Lark, his coat fine enough to make him stand out against the rough crowd, his hair sllicked back, his mustache curled with deliberate precision. Mary froze at the sight of him, her whole body recoiling as though struck.

Her grip on Clara tightened until the child whimpered again. Lark’s eyes lifted lazily from his cards, landing on Mary with a gleam of triumph. “Well, well,” he drawled, rising with exaggerated grace. “The widow Dalton thought you’d be smart enough to vanish, but here you are parading your brats for all to see. Saves me the trouble of rounding you up.

” Mary’s breath hitched, her knuckles white against her shawl. Thomas stepped between them, his broad frame casting Larkin shadow. You’ll not touch them. Lark’s smile widened. And who might you be? The good Samaritan, the hero rancher. He circled Thomas, eyes flicking to Mary, then the children. Tell me, Mary, did you weep your way into his home the way you’ve wept into mine? Mary flinched, shame flooding her cheeks, though she had no guilt to carry.

Thomas’s hand twitched toward the knife at his belt, but he steadied himself. You’ll call her by her name, Lark. widow Dalton. Nothing else. The collector chuckled low and mocking. Names don’t matter when debts are owed. Next week the block is ready. These children will fetch a fine price. Buyers are already lining up. He leaned in close, his voice a venomous whisper, and no rancher with empty hands is going to stop me. Thomas’s eyes narrowed.

He had nothing to bargain with, no wealth, no allies in this den of wolves. Yet he knew one thing. He would not walk out of cold river without Mary and her children safe at his side. The saloon air thickened, silence pressing as men around the table sense the crack of lightning in the air. One wrong word, one wrong move, and fists, or worse, would fly. Mary’s breath came fast.

Her children pressed to her side. Samuel clenched his fists. Ruth buried her face again. Clara whimpered into her mother’s shawl. And Thomas Avery, lonely rancher turned reluctant protector, squared his shoulders against the storm about to break. The saloon had gone quiet, the air charged with the weight of words that could not be taken back.

Henry Lark stood with his smirk carved deep into his thin face, his fingers playing idly with the gold chain on his vest. Men around the tables leaned back, cards and glasses forgotten, their eyes darting between the collector and the rancher who dared to stand against him. Mary clutched her children close, her shawl trembling as much as her hands.

Samuel stood in front of Ruth, chin high, as though his scrawny frame might shield her. Clara whimpered against Mary’s shoulder, burying her face in the fabric, her small breaths hot with panic. Thomas Avery didn’t move, didn’t flinch. His broad shoulders blocked Mary from view.

His presence alone a wall between her and the man who threatened her children’s future. His voice, when it came, was low, steady, and cutting. Then let’s speak plain, Lark. You say debts are owed. Fine. Show the papers. Show me proof you’ve got claim enough to take children from their mother. A murmur rippled through the room. Some men shifted uneasily, others chuckled darkly, eager to see the confrontation break into blows.

Henry Lark’s smirk only deepened. “You want papers, Rancher? You’ll have them at the auction block. That’s all the proof the law requires.” His voice dropped into something colder, meant for Thomas alone. “And if you think you can outbid buyers from Fort Yuma and the silver camps, you’re more fool than I thought.” Mary’s knees buckled, but Thomas caught her before she sank.

His hands steadied her shoulder, his gaze never leaving Lark. “There won’t be an auction,” Thomas said, each word heavy as iron. Lark’s laughter rang sharp, bouncing off the saloon’s warped boards. “And what do you do, Avery? You going to buy them yourself? With what herd? With what fortune? You’ve nothing but dirt and silence at that ranch of yours.

Men like me?” He tapped the ring on his finger against his glass. The sound like a gavl. Men like me decide what happens in cold river. The words hung there, but beneath the surface something stirred. A few men shifted, eyes narrowing at Lark’s arrogance. They tolerated him long enough, profited from his games, but even the hard-hearted found unease in the notion of selling children like cattle. Thomas saw it.

He read it in their faces. the flicker of shame, of hesitation. He pressed the moment. I’ve buried enough in this land to know what it costs to lose a family. Any man here who calls himself decent knows the truth. Children aren’t a debt to be traded. Their flesh, blood, and breath given by God himself.

You put them on a block, and you spit on every grave dug for honest folk in these parts. Silence fell heavier now, charged with something sharper than fear. Conviction. Mary’s tears flowed unchecked, but her eyes fixed on Thomas, wide and disbelieving. No one had spoken for her like this.

Not since her husband, not since the fire, not since the day she’d been left to scrape and beg at the mercy of wolves. Lark’s face twisted, his smirk cracking into a snear. You think words will save her, Avery? You think a speech in this hole will scare me? No. This town feeds on the weak, and she is the weakest I’ve seen. You stand in my way, you’ll starve alongside her. Thomas took one step closer. The boards creaked beneath his boot.

His eyes locked on larks with a fire that did not waver. Better to starve in the light than feast in the dark. And if you think I’ll bow to you, you don’t know me. The tension broke like glass. Lark swung first, his fist crashing toward Thomas’s jaw. But the rancher had been ready. He caught Lark’s wrist midswing, twisting until the collector’s knees buckled.

Gasps rippled through the saloon as Thomas slammed him against the bar, glasses shattering at the impact. Men surged to their feet, some eager for a fight, others frozen by shock. Mary cried out, clutching her children tighter. Samuel pulled Ruth behind him, his fists clenched. though his knuckles were white. Lark struggled, spitting rage. You’ll regret this, Avery.

You’ll regret the day you crossed me. Thomas’s voice thundered above the den. No more children on your block, Lark. Not hers, not anyone’s. The bartender, a grizzled man who’d seen too many brawls, stepped forward, his shotgun raised. Out both of you, take it to the street if you must, but not here.

Thomas released Lark, who stumbled back, clutching his wrist. His face burned crimson, his pride wounded deeper than his flesh. He straightened, adjusting his coat with trembling hands, and fixed Thomas with a look that promised retribution. “This isn’t over,” Lark spat auction s in 7 days, and I’ll see the widow there, even if I have to drag her myself.

He stormed from the saloon, his men trailing behind, their eyes darting uneasily toward Thomas as they followed. The room exhaled. Men returned to their tables, though whispers swirled like smoke in the air. Thomas turned, his gaze finding Mary. Her face was pale, her lips trembling, but her eyes shone with something fierce.

Fear still, but threaded now with the fragile thread of belief. He extended his hand to her. She took it, her fingers shaking as they curled around his. Samuel and Ruth pressed close, Clara still tucked against her mother’s shoulder. Together, they stepped out into the street, the late son casting long shadows over the dirt. The silence outside was thicker than the saloon smoke.

Mary clutched Thomas’s arm, her voice breaking. He’ll come. He’ll send men. He’ll take them. Thomas steadied her with his gaze. Then we’ll be ready. He won’t take them, Mary. Not while I stand. The promise lingered, but even as the words left his mouth, Thomas felt the weight of what they meant.

Lark was powerful, backed by money and men who thrived on fear. A single rancher could not stand alone against such a force. But he was no longer alone. He looked at Samuel, at the boy, s clenched jaw and determined stare. At Ruth, trembling but resolute. At Clara, whimpering softly, her innocence a reminder of what they fought for.

And at Mary, her eyes brimming with tears, yet shining with a strength she herself didn’t believe she carried. Thomas Avery, once the loneliest man on the prairie, now bore the weight of four souls, and he knew he would carry it to the end, no matter what storm it brought. The next days were not quiet. Word spread like wildfire through cold river. Some whispered that Avery had lost his senses, standing against a collector who owned half the valley.

Others whispered something else. That perhaps the rancher was right. That perhaps it was time someone said no. Mary worked beside Thomas at the ranch, her hands blistering as she mendied, scrubbed, and cooked, determined to repay kindness with labor. Samuel followed Thomas like a shadow, learning to mend fences to haul water to feed cattle.

Ruth stayed close to her mother, helping where she could, while Clara’s laughter, faint but real, began to warm the cabin walls. But every sunset carried dread. Seven days would pass too quickly, and with them the shadow of the block loomed nearer. One evening, as the family gathered by the fire, Thomas sat sharpening his knife, the steady scrape filling the room.

Mary’s handstilled on the mending in her lap. Her eyes met his. “You can’t face him alone,” she whispered. Thomas lifted his gaze, the fire light glinting off the blade. “Then I won’t. Not alone.” Mary frowned, uncertain. “What do you mean?” He leaned forward, his voice firm. “There are men in this valley who have lost to Lark. Men he’s bled dry.

Men he’s humiliated. They’ve stayed silent out of fear. But if they knew someone was willing to stand, maybe they’d find their voices again. Mary’s breath caught. And if they do, Thomas’s eyes softened, his voice lowering. Then I’ll still stand, even if I stand alone. The fire crackled, filling the silence between them.

Samuel’s eyes shone with awe. Ruth clutched her mother’s sleeve, and Clara’s tiny fingers played with the edge of Mary’s shaw. Mary swallowed hard, her heart torn between fear and something deeper, something like faith. Outside, the night spread cold and vast. The stars blinked sharp above the land, silent witnesses to promises made in fire light.

And in the hush, the widow and the rancher sat across from one another, bound not by blood, but by a cause that reached beyond them both. Seven days. Seven days to gather strength to turn whispers into courage to stand against the storm bearing down on them. And somewhere in the dark Henry Lark sharpened his own plans, his pride wounded, and his hunger for vengeance wetted sharper than any blade.

The wind shifted that night, carrying with it the low hum of change, as if the valley itself braced for what was to come. Thomas rose before dawn, his boots thutting across the cabin floor while the family still slept in the warmth of borrowed quilts. He moved with quiet purpose, lighting the lantern, pouring coffee, then pulling on his coat as though the day demanded every ounce of him. Outside, Frost still clung to the earth.

He saddled his horse, the leather creaking beneath his weight, and rode toward the nearest homestead. His thoughts were sharp and heavy, like the axe he carried to split wood. Henry Lark thrived on silence, and fear had been his greatest ally. If Thomas was to break him, he couldn’t do it with fists alone.

He needed men, neighbors, farmers, ranchers who had bent their necks under Lark’s yoke, men who had lost as Mary had lost. The first man he called on was Ezra Pike, a stooped rancher whose hands were gnarled from decades of toil. Ezra had buried a wife and son after sickness, and rumors said Lark had taken his herd soon after, claiming unpaid interest on a loan that Ezra swore he never took. The old man answered the door with suspicion etched in his face.

But when Thomas laid out the truth, that lark meant to sell Mary Dalton’s children at the block, Ezra’s eyes burned with something raw. “Children,” Ezra rasped, that devil’s gone lower than even I thought. He leaned heavily on his cane, nodding once. “You’ve got my word, Avery. I’ll stand.” By midday, Thomas had gathered three more. Calibb Jensen, who’d lost his land to forged papers.

Markhamm, who had seen his brother driven off by Lark’s thugs, and Isaac, a quiet farmer with scars across his back from a lesson Lark’s men had once delivered. Each man carried the weight of defeat. But when Thomas spoke, when he reminded them of graves dug, homes lost, and families torn apart, their silence cracked into resolve.

When he returned to his cabin, Mary was at the table, her hands still raw from work, sewing torn hems with trembling fingers. She looked up at him, her eyes searching his face. Clara played at her feet. Ruth peeled potatoes at her side, and Samuel waited by the door, his jaw tight. Well, Mary asked. Thomas hung his hat, then met her gaze squarely. We’re not alone anymore. Others will stand with us.

Her lips parted, a soundless prayer spilling through. She pressed her hands to her mouth, eyes wet. Ruth smiled faintly, though her hands kept moving. Samuel straightened, his young chest swelling with a pride he tried to mask. Clara clapped her hands, though she understood none of it. For a moment, hope sat with them at the table.

It wasn’t loud, wasn’t triumphant, but it glowed faintly like the hearth fire against the gathering storm. The following day, Thomas rode into Cold River again, this time with Mary and Samuel trailing on foot. Ruth stayed behind with Clara, too young to face the rough edges of town.

As they entered, heads turned once more, whispers buzzing through the streets like gnats. Some voices mocked, others held unease. Mary held Samuel’s hand, her fingers cold and clammy, but her spine straightened as Thomas walked before them. He didn’t take them to the sheriff.

Instead, he led them to the church, its steeple leaning slightly under the weight of years. Inside, Reverend Cole stood polishing the pews, a thin man with tired eyes, but a voice that still carried on Sundays. Reverend Thomas greeted his voice steady. We need your help. Cole looked up, brows furring at the sight of Mary and Samuel. This about the talk in town about Lark in the auction.

Mary’s voice broke through before Thomas could speak. It’s true, she whispered. He means to sell them, my children like cattle. Please, Reverend, you’ve preached of justice, of mercy. Will you stand with us? The reverend set down his cloth, his hands trembling slightly. He looked at Mary at the boy clinging to her side, then at Thomas.

For a long moment, he said nothing, the silence weighing heavy. Then he drew a deep breath. “I’ve buried too many in this valley because men with power thought themselves above God’s law,” he said finally. “I’ll not see children added to that count. I’ll stand.” Mary wept, clutching Samuel close, her body shaking with relief.

Thomas nodded once, a rare glint of something like gratitude in his eyes. The days bled into one another, each dawn bringing another neighbor, another voice added to their cause. By the fifth day, Thomas had gathered a small band, ranchers, farmers, even a blacksmith and two widows, each scarred in some way by Lark’s greed. They weren’t soldiers.

They weren’t outlaws, but they carried hammers, axes, shotguns rusted with age, and most of all, a fire long starved but not extinguished. Mary worked among them, her strength surprising even herself. She cooked meals, patched clothing, tended to children who clung to her skirts, and when asked, she spoke, her voice trembling but clear.

She told them what it was to beg for mercy at Lark’s hand, what it was to hear the words auction and children in the same breath. Each story hardened resolve. Each tear shed added to the river swelling against Lark’s dam of fear. Yet, as their numbers grew, so did the shadows. Lark’s men roamed the valley, knocking on doors, spreading threats. One morning, Samuel spotted a figure on the ridge watching the cabin before vanishing into the trees.

Another evening, a stone shattered the cabin’s window with a note tied to it. One week, the block is waiting. Mary clutched the note, her hands trembling so badly she nearly tore it in half. Thomas took it from her gently, folded it, and placed it in the fire. He didn’t speak, but the look in his eyes was enough. He would not yield. On the eve of the seventh day, the cabin swelled with voices.

Men sat shouldertosh shoulder, women clustered near the fire, children drowsing in corners. The air carried the weight of decision, of fear tangled with faith. Reverend Cole stood by the hearth, his voice ringing steady despite his frail frame. “Evil thrives when good men stay silent,” he said. “But we are no longer silent.

Tomorrow Henry Lark will expect obedience. Instead, he will find resistance.” Mary sat with Clara asleep in her lap. Ruth pressed against her side, Samuel standing tall beside Thomas. Her heart pounded so hard she feared it might break her chest. Yet as she looked around, she saw not fear alone, but strength reflected in every weary face.

Thomas rose, his voice cutting through the murmurss. Tomorrow we stand, not as scattered neighbors, but as one. Lark will come with his men. He’ll bring threats, maybe worse, but he won’t take these children. Not these, not any. The room hummed with agreement, fists clenched, heads nodded, voices rose in murmured prayer.

Mary’s eyes burned as she looked at Thomas. She saw not just the rancher who had opened his door, but the man who had opened a path where none seemed possible. For the first time in months, perhaps years, she believed deliverance was not just a word spoken on Sundays, but a promise carved into flesh and bone.

Outside the wind howled through the pines, carrying with it the scent of snow and the shadow of what awaited. The night stretched long, but sleep did not come easy. In every corner of the cabin, hearts beat with dread and hope interwoven. And in the dark Henry Lark gathered his men, his fury sharpened into cruelty. He polished his boots, straightened his coat, and prepared to claim what he believed was already his.

Morning would decide whether justice or greed would own cold river. Dawn came gray and brittle, the kind of morning where the sky seemed to hold its breath. Frost bit into the earth, the air sharp enough to sting the lungs. In the valley below, smoke from distant chimneys rose thin and hesitant as if the whole land knew what was set to unfold.

Thomas stood on the porch, rifle slung across his shoulder, his breath fogging in the chill. He scanned the horizon with the patience of a man who had spent years alone, his gaze steady, unyielding. Behind him, the cabin stirred with life. Mary coaxing Ruth and Clara into warm coats, Samuel pacing near the hearth like a colt, eager for a fight.

The boy’s fists clenched and unclenched, his eyes too old for his 12 years. Inside, the room was crowded. Ezra Pike leaned heavily on his cane, his eyes fierce despite the stoop in his back. Calb Jensen sat sharpening a hatchet, the scrape of steel grading in the tents quiet.

Reverend Cole stood near the door, his thin hands wrapped around a Bible, his lips moving in prayer that trembled but did not falter. The others, Maram, Isaac the blacksmith, and the two widows, busied themselves with last preparations, every motion stiff with dread. Mary moved among them like a thread holding the fabric together. She brewed coffee, pressed food into rough hands, whispered words of thanks that wo fragile courage into weary hearts.

Yet her own heart thundered so loud she feared they might hear it. She kept her children close. Every touch of Ruth’s small fingers, every sound of Claraara’s breath against her shoulder, a reminder of what was at stake. Samuel stood apart, his chin high, though his body quivered with anticipation. He wanted to prove himself, to shield his mother and sisters.

Mary’s gaze caught him, her breath catching with the sharp ache of seeing her boy standing on the edge of manhood far too soon. She crossed to him, cupping his cheek with trembling fingers. “Stay close to me,” she whispered. Samuel swallowed hard, his voice tight. I won’t let him take them, mama. Tears burned Mary’s eyes, but she forced a nod. We stand together.

That’s how we win. By midm morning, the sound came. Hoof beatats, dozens of them, steady and slow, echoing through the valley like a drum beat of doom. Heads lifted inside the cabin, conversation cut to silence. Mary froze where she stood, Clara’s whimper muffled against her neck.

Ruth clung to her skirt, her wide eyes brimming with fear. Samuel darted to the window, his breath fogging the glass as he peered out. They’re here, he whispered. Thomas’s jaw tightened. He stepped onto the porch, boots crunching against the frost. The others followed, spreading across the yard in a line that was uneven but resolute. Mary came too, though every instinct begged her to hide.

She would not, not now, not when the moment demanded her presence. Over the ridge, Henry Lark appeared to stride a black stallion, his coat dark as ink against the pale morning. Behind him rode a dozen men, each armed, their faces hard and cruel. They moved with the arrogance of wolves, certain the flock would scatter. Lark’s smirk returned the moment he saw the cabin.

The people gathered there, and above all Mary, with her children pressed against her skirts. Well, he drawled, raining in his horse before them. Look at this. His eyes swept the line of neighbors, lingering mockingly on Ezra’s cane, the widow’s trembling hands, the rusted tools clutched in fists. He tipped his hat. A congregation of fools. No one spoke. The silence was thicker than the frost, broken only by the snort of horses. Lark’s smirk deepened.

“You think you can stop me with this?” he gestured lazily at the ragtag group. “I have papers. I have the law. and in seven days time these children are mine to sell, unless of course you hand them over now and spare yourselves the trouble.” Mary’s breath hitched. She felt Ruth pressed tighter against her, Clara’s small hands clinging to her shawl. Samuel stood rigid at her side, his fists shaking.

She wanted to collapse, to weep, to beg, but Thomas stepped forward first. “You’ll not take them, Lark,” he said, voice steady as stone. Lark’s gaze fixed on him, sharp as a blade. Ah, the lonely rancher, he sneered. Always thought you too quiet to stir trouble. But here you are, puffing your chest like a rooster.

Tell me, Avery, how many graves are you willing to dig today? Because I’ll put you and every one of these sorry souls in the dirt before I walk away empty-handed.” Thomas lifted his rifle, not in threat, but in declaration. Then you’d better dig deep because none of us are moving. A murmur rippled through the line. Ezra tightening his grip on his cane. Calb hefting his hatchet. Reverend Cole’s voice rising in prayer.

Fear quivered in their bones, but resolve steadied their stance. Mary stepped forward, her children clinging desperately to her. Her voice trembled, but it carried clear across the yard. You’ll not sell my children, Henry Lark. Not while I have breath. Not while these people stand with me. Lark’s smirk cracked, his eyes narrowing.

You think these peasants can save you? That this this rancher will fight your battles. His voice rose sharp with fury. You’re nothing, Mary Dalton. Nothing but debt and dust. And when I’m done, your brats will cry for you from cages you’ll never see. Ruth sobbed. Clara whimpered. And Samuel lunged forward, his voice breaking in a shout. Leave her alone. Mary caught him, pulling him back, her heart tearing in two.

But Thomas stepped forward again, his voice cutting through the chaos. You’ve had your say, Lark. Now hear mine. You’ve stolen land herds pride, but you’ll not steal children. Not here. Not ever again. The line of towns folk shifted forward, their ragged weapons gleaming in the pale light. Ezra raised his cane like a staff. Calb’s hatchet glinted. Reverend Cole lifted his Bible high.

It wasn’t much, not against guns and steel, but it was enough. It was defiance. Lark’s face darkened, his smirk gone, replaced with something uglier. He raised his hand, signaling his men. Teach them what happens to those who forget their place. The air snapped taught. Horses pawed at the earth. Guns shifted in saddles, and the valley held its breath. Mary clutched her children.

Thomas’s rifle gleamed, and the neighbors braced themselves. Then the first shot rang out. It was Thomas’s. It was Larks. It came from the ridge above, a crack that split the morning wide. One of Lark’s men tumbled from his horse, his weapon clattering into the dirt. The rest of the riders jerked in shock, their heads snapping toward the sound.

From the trees, figures emerged. more men, roughclad ranchers, farmers, faces grim but eyes bright with resolve. They carried rifles, shotguns, pitchforks, whatever their hands could hold. Word had spread farther than Thomas knew, and now the valley itself seemed to rise against Lark. Lark’s stallion reared, his fury spilling into a roar.

You think you can stop me with this rabble? Thomas’s voice answered, thunder in the quiet. No lark, not rabble. Neighbors, families, decent men and women who have had enough. The ground shook with hoof beatats, the air thick with shouts. The fragile line of defense had become a wall, ragged but unbroken, stretching from the cabin to the ridge.

Mary’s tears spilled unchecked as she clutched her children. For the first time, she felt not just fear, but the stirring of deliverance. Lark’s eyes burned with hatred. His smirk long gone, he raised his gun, his men shifting nervously behind him. The valley braced, and as the wind howled low through the pines, the battle for cold river began.

The first moments after the shot echoed from the ridge, felt like the pause between lightning and thunder. A stillness that trembled, heavy with dread. Men on horseback jerked their reigns, faces pale as one of their own lay sprawled in the dirt, dust rising around his body. Henry Lark’s stallion danced beneath him, nostrils flaring, hooves tearing furrows into the frost hardened earth.

“Hold!” Lark barked, though his voice cracked under the weight of surprise. His men hesitated, caught between fear of him and the sight of rifles glinting from the ridgeline. Every eye darted upward where farmers, ranchers, and blacksmiths, men who had known hunger and humiliation at Lark’s hand, stood shouldertosh shoulder. “Thomas Avery didn’t waste the moment. He stepped forward, rifle steady, his stance unflinching.

It’s over, Lark,” he called, his voice rolling like thunder across the yard. “Your fears run its course. These people aren’t yours to bleed anymore.” Mary’s breath came ragged as she clutched Clara to her chest. Ruth pressed tight against her side. Samuel standing just before them, jaw clenched. Her heart pounded so violently she thought it might burst.

But her eyes never left the man who had promised to sell her children. She felt the trembling of her daughters, the raw heat of Samuel’s fury, and she knew in her marrow that if Thomas faltered now, everything would be lost. Lark’s sneer twisted his face, his eyes flashing with the rage of a man unaccustomed to defiance. He spat into the dirt.

You think a few pitchforks and prayer books can stand against me? I’ve bought sheriffs, judges, men twice your number. When the papers come, they’ll see those brats sold whether you stand or fall. The reverend’s voice rose behind Thomas, thin but unwavering. There is a higher law, Henry Lark, and today it will be obeyed. His hand clutched the worn leather Bible, his lips trembling in fervent prayer.

The crowd shifted. Ezra Pike, stooped, though he was, leaned on his cane as though it were a sword. Calb Jensen hefted his hatchet with both hands, his face grim. Isaac leveled an old shotgun, its barrel rusted, but steady.

The line of neighbors stretched wider as more figures emerged from the trees, their resolve as solid as the frost underfoot. Lark barked a laugh, though it carried more desperation than amusement. You fools, every one of you. You think you’ve won because you’ve gathered a mob. I’ll break you. I’ll grind you into dust and I’ll start with her. His gun arm swung suddenly, leveling at Mary.

Mary’s scream tore through the yard, instinctively pulling her children close. Samuel stepped in front of her, arms wide, though his body was trembling. Thomas moved faster. His rifle cracked, the bullet splintering the dirt just inches from Lark’s horse. The stallion reared, shrieking, nearly unseating its rider. Thomas’s voice roared above the chaos.

You’ll not touch them. Silence held in his wake, stunned and trembling. Then Reverend Cole’s voice broke it, soft but carrying like a benediction. He’s finished. He just doesn’t know it yet. Mary collapsed to her knees, her children clinging to her, sobs racking her frame. Relief and terror mingled, the enormity of what had been averted crashing down on her.

Samuel knelt beside her, his small hand on her back, his own tears falling though he tried to be strong. Ruth buried her face against her mother, and Clara whimpered, not understanding, but sensing the storm had passed. Thomas lowered his rifle, his shoulders sagging for the first time.

He turned to Mary, his gaze steady, his voice softer than she had ever heard. “It’s done. He won’t take them.” Mary lifted her tear streaked face, her lips trembling. “You don’t know what you’ve done for us.” Thomas shook his head slowly. No, Mary, we all did it. This valley stood, and it’ll keep standing. Around them, neighbors murmured in agreement. Ezra tapped his cane into the dirt with a nod. Calb sheathed his hatchet. Isaac lowered his shotgun.

On the ridge, rifles dipped, men exhaling in relief. The valley had found its voice again, and in that voice, Mary heard something she had thought lost forever. Safety. But even as she clutched her children tighter, a sliver of unease gnawed at her. Henry Lark had written off, but his words lingered like poison. This isn’t the end.

Mary knew men like him didn’t surrender. Not truly. He would return, perhaps not tomorrow, perhaps not next week, but someday when the valley’s guard lowered, when her children laughed too freely, and when he did, they would need more than courage. They would need each other. The sun crested the ridge, then spilling light over the frosted land, gilding the weary faces of those who had stood against the darkness. For now the day was theirs.

The sun rose higher, gilding the frost into glimmers of silver, as if the land itself wanted to mark what had happened. The crowd that had gathered at Thomas’s cabin stood in silence for a long time after Henry Lark and his remaining riders vanished into the trees. It wasn’t victory they felt. It was something heavier.

A mixture of relief, disbelief, and the weight of having stood against a tyrant and survived. Mary sank into the earth with her children clinging to her like vines to a tree. Her body shook as sobs racked her chest, not the helpless sobs of despair, but the trembling release of a woman who had held terror too long in her bones. Samuel tried to be brave, pressing his hand against her back, though tears streaked his face.

Ruth buried her little face in her mother’s shawl and whispered, “We’re safe, mama. We’re safe.” And Clara, still too small to understand, clapped her hands once and then fell into a fitful sleep against Mary’s shoulder. Thomas knelt in the dirt a few feet away, his rifle resting across his knees. He didn’t smile, didn’t let out a cheer.

His eyes remained fixed on the ridge where Lark had disappeared. Men like Lark didn’t vanish quietly. They regrouped, schemed, circled like wolves until they found weakness again. But in that moment, as he looked at Mary and her children, and then at the neighbors who had gathered, Thomas knew the valley had shifted. Fear no longer ruled outright.

Courage had drawn its first breath. Ezra Pike hobbled forward, his cane sinking deep into the frozen soil. His old voice cracked, but it carried with a strength that surprised even him. I thought I’d die bode to that man, but today he lifted his cane slightly, tapping it against the earth. Today we showed him he can bleed. Murmurss of agreement rippled through the gathered crowd.

Calb Jensen spat into the dirt, his eyes a light with something harder than anger. Resolve. Let him come back. We’ll be ready. Reverend Cole raised his hand, his voice trembling but steady. This day belongs to the Lord. We did not fight with hatred but with justice. Remember that when Lark returns, because he will. But so long as we stand together, he will never win.

Mary lifted her head, her tear streaked face glowing faintly in the pale light. She turned to Thomas, her lips parting as if to speak, but no words came at first. Finally, she whispered, her voice raw. Why? Why did you do this for us? Thomas met her eyes, his own shadowed but steady. He hesitated, the truth catching in his throat.

Because I lost once, a wife, a child. I thought I’d never bear that weight again. But when I opened that door and saw you standing there begging for your children, I knew I couldn’t turn away. Mary’s breath caught, her heart twisting. She pressed Clara closer, her other hand reaching for Ruth and Samuel. You gave us back more than life. You gave us a chance.

Thomas’s gaze softened, though sorrow lingered in the corners of his eyes. Then don’t waste it. You hold tight to those children. You let them laugh again. You let them live. The crowd began to disperse slowly, men and women murmuring, promising one another they would not let the valley return to silence. Some offered to patrol the ridges, others to watch Mary’s cabin by night.

Ezra clasped Thomas’s hand, his gnarled grip trembling. Calb tipped his hat to Mary, his eyes holding a rare gentleness. Reverend Cole lingered, whispering a final prayer over the children before mounting his horse. By noon, only a few remained, and soon it was just Thomas, Mary, and her children standing in the yard, the quiet pressing heavy after so much clamor.

The cabin door swung gently in the breeze, and the hearth smoke trailed into the gray sky. Mary’s knees weakened, and she sank onto the porch steps, her children clustering around her. Samuel leaned against her shoulder. Ruth pressed against her side, and Claraara curled into her lap, her thumb in her mouth. Mary stroked their hair, kissed their foreheads, whispered prayers into their ears.

Thomas stood a few paces away, his hands shoved deep into his coat pockets. He looked like he meant to speak, then thought better of it. He turned slightly, as if preparing to mount his horse and ride off into the hills. Mary’s voice stopped him. Don’t. He turned back. Her eyes met his, filled with exhaustion and fear, but also something new, something steadier. “Don’t walk away now,” she whispered.

“You’ve carried us this far. Don’t leave us to stumble again.” The plea pierced deeper than any weapon. Thomas looked at her at the children nestled against her at the cabin that already bore signs of their presence, quilts over chairs, a doll left forgotten near the door. his chest tightened, old wounds pulling taut, but he did not turn away.

He walked to the steps, lowering himself beside her. For a long moment, they sat in silence, the only sound the soft breath of children who had nearly been stolen. Mary leaned her head against his shoulder, tentative at first, then with the full weight of her weariness. Thomas didn’t flinch.

He let her rest there, his arm lifting slightly until it rested around her shoulders. The quiet stretched, but it wasn’t the heavy silence of loneliness. It was something different, fragile, tentative, but alive. That night, the cabin glowed with the light of the fire.

Samuel sat sharpening a stick into something like a spear, determination still carved into his face. Ruth hummed softly as she rocked Clara to sleep, her small voice weaving lullabibis remembered from gentler times. Mary moved quietly about the room, her hands steady as she laid out food, mendied a torn sleeve, tended to the hearth. Thomas sat at the table, his eyes following her, his heart heavy with thoughts he couldn’t quite speak.

Mary caught his gaze once, her cheeks flushing, but she didn’t look away. Tomorrow, she asked softly. Thomas nodded. Tomorrow he may come again, or he may wait, but he won’t forget. Mary’s hands trembled, but she forced a nod. Then tomorrow we stand again. Thomas’s lips tightened, not in a smile, but in something close together.

Morning broke pale and uncertain. Frost glistened on the fields, but birds sang faintly in the pines. Mary stepped outside with Ruth and Samuel, watching Clara toddle after them in the yard. Laughter, weak, hesitant, but real, spilled into the cold air as Samuel chased Ruth, and Clara stumbled clumsily, falling into her mother’s arms.

For the first time in months, Mary let herself smile. Tears glistened, but they weren’t just of sorrow. She looked toward the barn, where Thomas was mending a rail with steady hands, and she realized something undeniable. She and her children were no longer drifting souls waiting to be claimed.

They were tethered now, held fast by a man who had chosen to fight for them when no one else would. Thomas straightened, wiping sweat from his brow. His eyes met Mary’s across the yard, and for a fleeting moment the quiet loneliness that had haunted them both flickered into something else, something neither dared to name, but both felt all the same.

The wind shifted then, carrying the scent of pine and earth, carrying also the unspoken truth. Henry Lark was not gone. He would return someday with new schemes new cruelty. But when he did, he would find not silence, not despair, but a family broken once, bound now, and a valley that had found its voice again. Mary pulled her children close, whispering words of comfort they scarcely needed anymore. Samuel grinned faintly. Ruth’s eyes sparkled.

Clara giggled into her mother’s neck. And Thomas Avery, once the loneliest rancher on the prairie, looked upon them and felt, for the first time in many long years that he was not alone. The auction would never come. The block would remain empty, and the widow’s children, once marked to be sold, had been claimed instead by something more enduring than coin or law.

A promise spoken not with riches but with sacrifice.

News

I went into labor earlier than expected, and my husband, who was away on a business trip, couldn’t make it back in time.CH2

I went into labor earlier than expected, and my husband, who was away on a business trip, couldn’t make it…

An 8-Year-Old Girl Found Her Double at School—What the DNA Test Revealed Made Her Mother Tremble…CH2

An 8-Year-Old Girl Found Her Double at School—What the DNA Test Revealed Made Her Mother Tremble… The first time Emily…

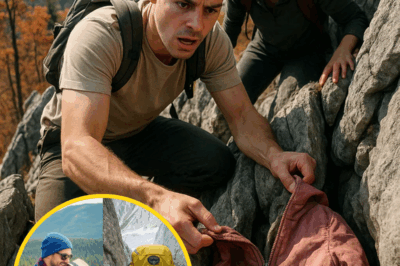

Five Years After Father and Daughter Went Missing in the Smokies, Hikers Discover What Was Concealed in a Rocky Crevice…CH2

Five Years After Father and Daughter Went Missing in the Smokies, Hikers Discover What Was Concealed in a Rocky Crevice…….

We don’t serve the poor here!” the waitress shouted. The waiter who insulted Big Shaq had no idea who he really was…CH2

We don’t serve the poor here!” the waitress shouted. The waiter who insulted Big Shaq had no idea who he…

They locked me the pregnant wife inside a freezer at −20°C, just to protect his mistress. But my husband never imagined that in doing so, he was digging his own grave…CH2

They locked me the pregnant wife inside a freezer at −20°C, just to protect his mistress. But my husband never…

Little Girl Sob And Begging “DON’T HURT US”. Suddenly Her Millionaire Father Visit Home And Shout…CH2

Little Girl Sob And Begging “DON’T HURT US”. Suddenly Her Millionaire Father Visit Home And Shout… Eight months earlier, his…

End of content

No more pages to load