They Called It “Suicide Point” — Until This Marine Shot Down 12 Japanese Bombers in One Day

At 09:00 on July 4th, 1943, the sun rose gray and low over Renova Island, barely cutting through the mist that clung to the shore. Private First Class Evan Evans crouched behind sandbags near the northern tip of the island, the area Marines had grimly nicknamed “Suicide Point.” His uniform was plastered with mud, soaked in sweat from the previous days’ relentless work. At twenty-two, Evan was young, but the Pacific had aged him beyond his years. He had been on Renova for three weeks, and in that time, he had yet to see his first downed plane. Now, sixteen Japanese Betty bombers appeared through the ragged clouds, glinting silver in the weak sunlight, their engines buzzing over Blanch Channel. He knew the stories: two days earlier, fifty-nine Americans had died on that same beach, victims of a similar strike, a bombardment that had come without warning and left only smoke, fire, and ash in its wake.

On July 2nd, the Japanese had sent eighteen bombers escorted by 440 fighters, targeting fuel dumps, ammunition depots, and the field hospital where wounded Marines waited for evacuation. The radar sets on Renova had already been knocked out by previous attacks, leaving the garrison blind. Evans had watched helplessly as bombs tore the beach apart. Explosions hurled debris hundreds of feet into the air, and flames devoured wooden structures and supply crates alike. Marines ran blindly through the inferno, trying to reach the wounded, but most didn’t make it. Seventy-seven men were injured that day, four of them from Evans’ own 90mm gun crew. Two of the six long-range 155mm artillery pieces belonging to the 9th Defense Battalion had been destroyed. Trucks melted under the fire, their engines and fuel tanks igniting in a chain reaction that seemed unstoppable.

For six hours, ammunition cooked off in random explosions, and the beach became a vision of apocalyptic chaos. Suicide Point was aptly named, for every supply ship had to pass it, and every Marine stationed on Renova could witness the carnage unfold. Evans and his gun crew had fired thirty-two rounds that day, none of them hitting their targets. The Betty bombers came too fast, and the men were working blind without radar. Gun directors attempted to calculate intercepts using binoculars and stopwatches, but human reaction and mechanical estimation could not match the speed of a plane moving at 270 miles per hour. By the time a shell reached altitude, the bomber was gone, leaving only smoke trails and destruction in its wake.

That night, Lieutenant Colonel William Shier gathered the 90mm crews. He was a man of few words, but the message was clear: the radar sets were destroyed, replacements would not arrive for days, and the Japanese would return. And when they did, it was uncertain how many Marines would survive to bury the dead. Evans cleaned his gun until the early hours of the morning, the massive M1 90mm anti-aircraft weapon looming over him like a mechanical giant. The gun itself weighed nine tons, could fire twenty-four-pound shells to thirty-three thousand feet, and had a maximum rate of twenty-eight rounds per minute. But all of that meant nothing without the guidance of radar.

Two days of relentless preparation had taught Evans and his fellow Marines the limits of their equipment and the lethality of the Japanese formations. The Mitsubishi G4M Betty bomber, with its eighty-two-foot wingspan, could cross two miles in twenty-seven seconds at top speed. Human eyes and stopwatches simply could not track it accurately. Evans’ battalion had landed on Renova on June 30th, tasked with defending the beachhead while Army artillery targeted Japanese positions across the channel on New Georgia. The plan had been straightforward in theory: three batteries of 90mm guns, four guns per battery, creating a protective umbrella of flak over the island. In practice, they had become target practice, a lesson in the cruelty of war.

The morning of July 3rd brought rain, a solid downpour that transformed Renova into a swamp. Marines stood guard duty in water up to their knees, supplies rotting on the beach. Yet the rain carried one small blessing: Japanese aircraft rarely flew in heavy weather. During those hours, the 9th Defense Battalion scrambled to repair what they could. Salvage teams scavenged parts from damaged guns and vehicles, mechanics worked tirelessly, and by dawn on July 4th, the radar operators reported that the SCR-268 sets were operational. Not perfect, but functioning. Gun directors checked their systems, fire control was green, and communications linked all twelve gun positions. Evans loaded shells into the ready racks, the familiar rhythm of preparation offering a sliver of reassurance amid the uncertainty.

By 08:45, radar detected a large formation approaching from Rabaul: sixteen bombers with one hundred and eighty fighter escorts, bearing down at 120 miles out. Shier gave the order to stand by, and every gun crew assumed their positions. This time, Evans’ battalion had radar, a tool that would allow them to see the Japanese coming, but it was not a guarantee of survival. For Evans, twenty-two years old and three weeks on a hellish island, this would be the moment that measured courage against chaos.

The Japanese formation split, a classic maneuver: one group veered toward New Georgia, while the other continued straight for Renova. The remaining bombers descended to twelve thousand feet, now well within the range of the 90mm guns but still high enough to evade lighter anti-aircraft fire. Renova’s combat air patrol had been drawn north to intercept a separate raid, leaving Evans and his battery isolated. His gun director, the Sperry M4 mechanical computer, was designed for optical tracking, not radar. The connection between radar feed and mechanical computation was awkward and imprecise, making the task of hitting a moving target a matter of skill, timing, and sheer nerve.

At 09:15, the air raid siren blared across the island, signaling the impending attack. Marines ran for foxholes, medics grabbed their kits, and the crowded beach emptied in seconds. All except the gun crews, who stayed at their posts, their focus unbroken. Evans checked his ammunition: high explosive shells with variable-time fuses. Each fuse could be adjusted in half-second increments, crucial for calculating detonation against a bomber moving at hundreds of miles per hour. A single second off meant a miss of hundreds of feet.

As the Japanese closed to thirty miles out, the first American shells began to burst at altitude. Black puffs of smoke appeared ahead of the formation. Near misses barely nudged the bombers off course. At fifteen miles, after firing eighty-eight rounds, Evans saw the moment of truth approaching. The lead Betty began its descent, dropping to eight thousand feet for its attack run. Wind and island position had to be accounted for. In three minutes, the bombers would be directly overhead, and in four, bombs would rain down on the beaches below. The gun barrel was heating rapidly; overuse threatened to warp the rifling and ruin accuracy. There was no time to stop. The Japanese weren’t waiting.

Every movement had to be automatic, every calculation precise, and every second counted. Evans and his crew moved through the familiar drill: load, ram, set fuse, fire. Each repetition carried the weight of life and death, the hope of survival, and the chance to turn the tide at a place already etched in Marine memory as Suicide Point. The approaching bombers, unaware of the danger they were flying into, would soon learn that the lessons of July 2nd had been absorbed, adapted, and amplified. Evans had become the pivot around which the next chapter of Renova’s defense would hinge.

At that moment, the Pacific hung heavy over the island, the roar of engines filling the sky, and the horizon seemed poised between disaster and possibility. One Marine, his fingers blistered and eyes strained, was about to prove that even a single 90mm gun, in the hands of a determined soldier, could rewrite the calculus of war. All that remained was whether he could survive the next six minutes. And whether the island would see the outcome.

Continue below

At 09:00 on July 4th, 1943, Private First Class Evan Evans crouched behind sandbags on Renova Island, watching 16 Japanese Betty bombers appear through broken clouds over Blanch Channel. 22 years old, 3 weeks on this muddy hell, zero aircraft shot down. The bombers were heading straight for what the Marines called suicide point.

2 days earlier, 59 Americans had died on this same beach. The Japanese had sent 18 bombers and 440 fighters on July 2nd. Renova’s radar sets had been knocked offline by a previous raid. No early warning, no time to prepare. The bombers came in low over the water at 1400 hours. They hit fuel dumps first, then ammunition, then the field hospital where wounded men were waiting for evacuation. Evans had watched it happen from his gun position.

Fire turned the beach into an inferno. Explosions threw debris 300 feet into the air. Marines ran through flames trying to reach the wounded. Most didn’t make it. 77 more were injured. Four of them were from the 9inth Defense Battalion’s 90mm gun crews. The battalion lost two of its six 155mm long tom artillery pieces. Trucks melted.

Ammunition cooked off for 6 hours. The Japanese had named their target well. Suicide Point sat on the northern tip of Renova. Every supply ship had to pass it. Every Marine on the island could see it burn. Evans and his gun crew had fired 32 rounds that day, hit nothing. The bombers came in too fast. The radar operators were working blind.

Gun directors were calculating intercepts with binoculars and stopwatches. By the time shells reached altitude, the Betty’s were gone. That night, Lieutenant Colonel William Shier gathered the 90mm crews. He didn’t waste words. The radar sets were destroyed. parts wouldn’t arrive for days. The Japanese would be back.

They always came back. And next time, there might not be enough Marines left to bury the dead. Evans cleaned his gun until 0300. The 90 mm M1 anti-aircraft gun weighed 9 tons. It could fire a 24-lb shell to 33,000 ft. Maximum rate of fire was 28 rounds per minute. But none of that mattered without radar.

The Japanese Mitsubishi G4M Betty bomber had a top speed of 270 mph. At that speed, a bomber crossed 2 m in 27 seconds. Human eyes and mechanical calculators couldn’t track fast enough. The 9inth Defense Battalion had landed on Renova on June 30th. Their mission was simple. Protect the beach head while Army artillery shelled Japanese positions on New Georgia across the channel.

The battalion had brought three batteries of 90 mm guns, four guns per battery, 12 guns total. They were supposed to create an umbrella of flack that no Japanese plane could penetrate. Instead, they’d become target practice. If you want to see how Evans and his crew turned Suicide Point into a graveyard for Japanese bombers, please hit that like button. It helps us share more stories about the Marines who fought in the Pacific.

Subscribe if you haven’t already. Back to Evans. The morning of July 3rd brought rain. Solid rain that turned Renova into a swamp. Marines stood guard duty in water up to their knees. Supplies rotted on the beach, but the rain brought one gift. The Japanese didn’t fly in heavy weather. The 9inth Defense Battalion used the time to repair what they could.

Salvage teams pulled parts from damaged equipment. Mechanics worked through the night. By dawn on July 4th, something had changed. The radar operators reported their SCR268 sets were operational. Not perfect, but operational. Gun directors checked their equipment. Fire control systems were green. Communications were established between all 12 gun positions. Evans loaded shells into the ready rack.

His crew moved through their drills. Loader, rammer, fuse setter, gunner. They’d done it 10,000 times in training, but training didn’t prepare you for Betty’s dropping bombs on your friends. At 0845, radar detected a large formation inbound from Rabauul. Distance 120 mi, bearing 320°, altitude 14,000 ft.

The formation was flying straight down the slot, headed for Renova. Sh gave the order. Every gun crew stood ready. This time they had radar. This time they would see the Japanese coming. And this time, Evan Evans was about to prove that one marine with a 90mm gun could change the mathematics of air defense forever. The question was whether he’d live long enough to see it. The radar operators called out updates every 30 seconds.

The Japanese formation had split. One group turned toward New Georgia. The other kept coming straight at Renova. 16 bombers, 180 fighters as escort. They were descending now. 12,000 ft. The combat air patrol had been pulled north to intercept a different raid. Renova’s guns were alone.

Evans watched his gun director. The director was a Sperry M4 mechanical computer. It received radar data and calculated where the shells needed to explode to intercept a moving target. The director sent electrical signals to the gun mount. The mount adjusted automatically in theory. In practice, the M4 was designed for optical tracking. It was never meant to work with radar. The connection was awkward, imprecise.

The best gun crews could get their shells within 200 meters of the target. A 90 mm shell had a burst radius of about 50 m. That meant you needed multiple guns firing to have any chance of a hit. But Evans didn’t have multiple guns. He had one. Battery C, gun three. The formation reached 70 mi out.

The radar plot showed them in a tight V formation. textbook Japanese bomber tactics. The Betty’s would come in at medium altitude, drop their bombs, turn hard, and run for home while the Zeros dealt with any fighters that tried to pursue. Renova had no fighters. At 09:15, the air raid siren began its whale.

Every marine on the island knew what that sound meant. Men ran for foxholes. Medics grabbed their kits. The CB stopped unloading supply ships and took cover. The beach that had been crowded with activity 30 seconds earlier was suddenly empty. Except for the gun crews, they stayed at their positions. Evans checked his ammunition, high explosive shells with variable time fuses.

The fuse setter could adjust detonation time in half-second increments. At 10,000 ft, a shell traveled for about 18 seconds before exploding. If the timing was wrong by even 1 second, the shell would burst too high or too low, miss by half a mile. 50 mi out now. The Japanese were at 10,000 ft and holding steady.

That altitude put them above most of the light anti-aircraft fire, but well within range of the 90 mm guns. The bomber crews knew Renova had big guns. They’d seen the flack 2 days ago. They weren’t worried. American anti-aircraft fire was notoriously inaccurate. The Japanese had been flying through it for 18 months. Most crews considered it more of an inconvenience than a threat. They were about to learn otherwise.

At 30 m, Shier gave the order to commence firing. All 12 guns opened up simultaneously. The sound was overwhelming. Each gun fired a shell every 3 seconds. 24-lb projectiles screamed into the sky at 2,800 ft pers. The noise made speech impossible. The concussion from the muzzle blast knocked dust off sandbags. Evans settled into the rhythm.

His crew had practiced until every movement was automatic. The loader grabbed a shell from the ready rack. The rammer shoved it into the brereech. The fuse setter dialed in the time. The brereech closed. The gun fired. The empty shell casing ejected. The whole sequence took 3 seconds. Load, ram, set, fire.

Load, ram, set, fire. The radar operators were tracking the Japanese formation with precision. Now, the repaired SCR268 was feeding data to the gun directors faster than the mechanical computers could process it. The M4 calculators were clicking and worring. Elevation and azimuth changed constantly as the bombers approached.

20 mi out, the first American shells began bursting at altitude. Black puffs of smoke appeared in the sky ahead of the formation. Too far left, the Japanese adjusted course slightly. Kept coming. Evans watched through the gunsite as his shells exploded 500 m from the lead bomber. Close, but not close enough. The Betty bomber had a wingspan of 82 ft. A near miss meant nothing.

Only direct hits or very close bursts could bring down a bomber that size. 15 miles. The Marines had fired 88 rounds. And then something changed. Something that would turn Evan Evans from an unknown private into the deadliest anti-aircraft gunner in the Pacific.

But first, he had to survive the next 6 minutes because the Japanese bombers were about to start their attack run. And Evans was directly in their path. At 12 mi, the lead Betty bomber began its descent. The Japanese formation dropped to 8,000 ft. Attack altitude.

The bombaders would be looking through their sights now, calculating wind speed, adjusting for the island’s position. Renova was a stationary target, hard to miss. The radar operators updated their tracking. The Japanese were coming in from the northwest at 260 mph. In 3 minutes, they’d be directly overhead. In 4 minutes, they’d be dropping bombs. Evans kept firing. His gun was heating up now. The barrel temperature was rising with each shot.

Too hot and the rifling would warp. The gun would become inaccurate. But there was no time to let it cool. The Japanese weren’t waiting.

Load. Ram. Set. Fire. At 10 mi, something happened that changed everything. Battery C’s gun director locked onto the lead bomber. The radar return was strong, clean. The M4 computer began calculating intercept solutions with unusual precision.

The gun elevated 2°, adjusted azimuth 3° left. Evans fired. The shell left the barrel at half a mile per second. Climbed through 8,000 ft of tropical air. The variable time fuse counted down. 18 seconds after leaving the gun, the shell exploded. 200 m ahead of the lead Betty. The bomber flew straight into the blast. Shrapnel tore through the right engine. howling. The engine caught fire immediately. Black smoke poured from the NL.

The pilot tried to maintain formation. The Japanese didn’t break formation easily. Training and discipline kept them flying straight, but the fire spread. Within 30 seconds, flames were visible along the entire right wing. The bomber dropped out of formation, started losing altitude. The pilot had two choices.

try to reach Renova and drop his bombs or turn back toward Japanese- held territory and hope to crash land somewhere survivable. He chose to turn back. The Betty rolled right and began a shallow descent toward the channel. It never made it. At 6,000 ft, the right wing separated from the fuselage.

The bomber tumbled out of the sky and hit the water 4 mi northwest of Renova. One down, 15 to go. The remaining bombers tightened their formation. They were at 7 mi now, close enough that Evans could see them without binoculars. The Betty’s looked like dark crosses against the morning sky. Their bomb bay doors were opening. Battery C fired again and again. The other 90mm guns across Renova joined in.

The sky filled with black bursts. The Japanese formation disappeared into a cloud of flack. When the smoke cleared, two more betties were trailing smoke. One had lost its tail section. It went into an immediate spin. The other tried to maintain altitude, but was losing power from both engines. Neither made it past 5 mi from the island. Three down.

The Japanese bombarders released early. They were supposed to fly directly over Renova before dropping. Instead, they dumped their loads at 6 mi out and turned hard to the west. Bombs fell into empty ocean. Massive geysers of water erupted half a mile from shore. Not a single bomb hit the island.

Evans didn’t stop firing. His crew didn’t pause. The Japanese were running now, but they were still in range. The Betties were fast, but they’d spent fuel getting to Renova. They were heavy with armor and defensive guns, and they were trying to climb to escape the flack. Climbing made them slower. Predictable.

Battery C’s gun director tracked a bomber in the middle of the formation. Evans adjusted his aim. Fired. The shell burst 50 meters below the bomber’s belly. Close enough. The concussion wave hit the aircraft like a hammer. The Betty’s nose pitched down. The pilot fought for control. He didn’t get it.

The bomber entered a dive it couldn’t recover from. Four down. The remaining 12 Betty’s were splitting up now. Formation discipline had broken. Each pilot was flying for his own survival. Some headed west toward New Georgia. Others turned northwest back toward Rabool. The zero escort had disappeared entirely. The fighters had seen enough. But the Marines hadn’t.

And in the next 60 seconds, Evan Evans and Battery C were about to add eight more bombers to their tally. Eight more kills that would make July 4th, 1943 the single deadliest day in the history of Japanese naval aviation over the Solomons if the gun barrel held out. The gun barrel was glowing now.

Evans could see heat waves rising from the metal. The crew had fired 42 rounds in 7 minutes. The 90mm M1 was designed for sustained fire, but not like this. Not at this rate. The barrel temperature was approaching critical levels. Evans didn’t care. Neither did his crew. They kept loading.

A Betty bomber broke west trying to escape over New Georgia. It was climbing hard. 9,000 ft. The pilot thought altitude would save him. It didn’t. Battery sees radar locked on. The gun director calculated the intercept. Evans fired twice in quick succession. The first shell missed high. The second shell exploded 30 meters behind the bomber’s tail. Shrapnel severed the elevator controls. The Betty’s nose dropped.

The pilot tried to compensate with engine power. The bomber went into a flat spin and crashed into the jungle 3 mi inland on New Georgia. Five down. Two more Betties were heading northwest together. They were flying low now. 5,000 ft. Trying to stay under the radar. It didn’t work. Renova’s SCR268 could track targets down to 3,000 ft.

The gun directors had clear returns on both aircraft. Battery C took the lead bomber. Battery E took the trailer. Both guns fired within seconds of each other. Both scored hits. The lead Betty took a direct hit to the port engine. The engine exploded. The wing folded. The bomber rolled inverted and went straight down into Blanch’s channel.

The second Betty lost its tail section. It flew for another 8 seconds before entering an uncontrollable dive. Seven down. The sky over Renova was filled with smoke now. Burning aircraft debris was falling into the ocean. Oil slicks spread across the water. The remaining nine Japanese bombers were scattered across a 10-mi radius.

No formation, no coordination, just individual pilots trying to survive. Three Betty’s turned due west heading for the open ocean. They were abandoning the mission, running for home. But home was 400 m away, and they had to cross 200 m of ocean that was now filling with American shells. Battery C tracked the nearest bomber. Range 8 mi, altitude 7,000 ft. Speed 280 mph.

The bomber was running at full power, probably burning fuel at twice the normal rate. The crew would be lucky to make it halfway to Rabul before they ran dry. They didn’t get the chance. Evans fired three rounds. The third one exploded directly underneath the bombers’s fuselage. The blast tore through the bomb bay. The Betty hadn’t dropped all its ordinance.

500 lb bombs detonated inside the aircraft. The explosion was massive. Pieces of the bomber scattered across half a mile of ocean. Eight down. The other batteries across Renova were getting hits now, too. Battery E claimed two more bombers in quick succession. Battery A got another. The sky was becoming a shooting gallery.

The Japanese had sent 16 bombers to destroy Renova. Instead, Renova was destroying them. Evan swung his gun to track another Betty. This one was heading due north. Maximum range, 10 mi out. The bomber was at 11,000 ft and climbing. The pilot had figured out that altitude was his only chance.

Get high enough and the American shells couldn’t reach him, but 11,000 ft was well within the 90 mm range. The M1 could fire effectively to 33,000 ft. This bomber was barely a third of that. Evans elevated the gun to maximum. Fired. The shell climbed for 22 seconds, exploded 200 m ahead of the bomber. The pilot saw the burst and turned hard right directly into the next shell.

The blast hit the cockpit. The Betty’s nose shattered. The aircraft tumbled out of control and fell into the ocean 9 mi north of Renova. Nine down. By 09:30, the sky was clearing. The Japanese attack was over, broken, destroyed. Of the 16 Betty bombers that had approached Renova, only four were still flying.

They were heading northwest at maximum speed, climbing, running. The Zero Escort had already abandoned them and fled back toward Rabal, but Battery C wasn’t finished. Evans tracked one of the retreating bombers. Range 12 mi. Maximum effective range for accurate fire. The bomber was at 14,000 ft on the edge of the flack zone. Evans fired anyway.

The shell arked through the sky, exploded 300 meters from the bomber, too far for a kill, but close enough to send a message. Renova wasn’t suicide point anymore. It was a killing ground, and the Japanese had just learned that the hard way. The question was whether they’d be back tomorrow, and whether Evans and his gun would be ready.

The ceasefire order came at 09:32, 27 minutes after the first radar contact. The guns fell silent. The sudden quiet was almost painful after the continuous roar of the 90 millimeter cannons. Evan stepped back from his gun. His hands were shaking, not from fear, from exhaustion. His ears were ringing so badly he could barely hear. The gun crew collapsed against the sandbags.

They’d been firing non-stop for 27 minutes. Load, ram, set, fire. over and over until their bodies moved on pure muscle memory. The gunner’s log showed 53 rounds fired from battery C’s gun 3 alone. Across Renova, the 12 90mm guns had expended a total of 88 rounds. 88 shells to engage 16 bombers. The results were unprecedented. Shy walked the gun line at 010. He was counting.

Every gun crew was claiming kills. Some crews claimed two. Battery C claimed four confirmed. Battery E claimed three. Battery A claimed two. The math was adding up to something extraordinary. By 0:30, the radar operators confirmed what the gun crews already knew. Four Japanese bombers had escaped. Four out of 16. That meant 12 had gone down. 12 bombers destroyed in 27 minutes.

The 9inth Defense Battalion had just set a record. No American anti-aircraft unit in the Pacific had ever achieved that kill ratio. Not at Guad Canal, not at Midway, not anywhere. 12 bombers with 88 rounds meant a hit rate of nearly 14%. Most anti-aircraft units were happy with 2%. But the numbers didn’t tell the whole story. The gun crews had done more than shoot down airplanes.

They’d broken a Japanese attack completely. 16 bombers had approached Renova carrying 8,000 lb of bombs each. That was 128,000 lb of high explosives meant for the beach, for the supply dumps, for the Marines. Not one bomb hit the island. The Japanese had dumped their loads early and run. The four bombers that escaped were damaged.

Radar tracked them limping northwest at reduced speed and altitude. Two of them probably wouldn’t make it back to Rabau. They’d run out of fuel somewhere over the Solomon Sea and ditch in the ocean. By 1100 hours, work parties were recovering debris from the water. Pieces of Japanese aircraft were washing up on the beach.

Engine cowlings, wing sections, a tail assembly with the red circle still visible. The wreckage spread across 5 miles of ocean. The seabbes returned to unloading supply ships. The beach came back to life. Marines who’d been hiding in foxholes emerged and went back to work. Life on Renova continued. But something had changed.

The island that had been called Suicide Point 2 days ago had just proven it could defend itself. Evans cleaned his gun at 1300 hours. The barrel was too hot to touch even 3 hours after the last shot. The rifling was still intact. No warping, no damage. The M1 had held up under punishment that should have destroyed it. The other gun crews were doing the same, cleaning, inspecting, reloading. The Japanese would be back.

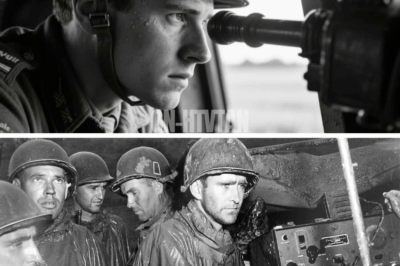

They always came back. But next time, they’d remember July 4th. They’d remember that Renova wasn’t an easy target anymore. At 1500 hours, a photographer from the Marine Corps combat camera unit arrived at Battery C. He wanted pictures. The gun crew that had scored the most kills. Evans and his crew stood beside their 90mm gun.

Boon on the left, Evans in the middle, Gamberowski on the right. Three Marines who just made history. The photographer took six pictures. Only one survived the war. It ended up in the National Archives as photo 127GW. The caption read, “This is one of the anti-aircraft guns which wiped out a Japanese bomber fleet of 12 planes in a single day at Renova Island.

” But that photograph was taken in the afternoon. In the morning, while the battle was still being analyzed, while gun crews were still counting their kills, something else was happening 400 m northwest. At Rabau, Japanese commanders were receiving reports from the four bombers that had escaped. The reports were alarming.

The Americans had radar directed anti-aircraft fire, accurate radar, the kind that could track bombers through clouds and guide shells to within meters of the target. And that meant every Japanese air base in the Solomons had just become vulnerable. Because if Renova could do this, other American positions could too.

The mathematics of air combat in the Pacific had just changed. The Japanese would need to adjust their tactics or stop flying daylight raids altogether. But that decision would take days to make. And in those days, Evan Evans and the 9inth Defense Battalion would face something even more dangerous than bombers. They would face their own command.

The first message from Admiral Hallyy’s headquarters arrived at 1600 hours on July 4th. It was short, three words, confirm kill count. Sher confirmed. 12 Japanese Betty bombers destroyed. Four damaged and fleeing. 88 rounds expended. Zero American casualties during the engagement. Zero bombs hit the island. The second message arrived 30 minutes later.

This one was longer. Hollyy wanted a full afteraction report. He wanted to know how a Marine defense battalion had achieved a 90% destruction rate against a Japanese bomber formation. He wanted technical details, radar settings, fire control procedures, everything. Because if Renova could do this, every American position in the Pacific needed to know how.

Shent the evening of July 4th writing reports. The radar operators wrote reports. The gun directors wrote reports. Every gun crew documented their procedures. How they’d integrated the SCR268 radar with the Sperry M4 gun director. How they’d adjusted for the lag in the mechanical computer. How they’d calculated lead time for fastoving targets.

The reports went up the chain of command from Renova to 14th Corps headquarters, from 14th Corps to South Pacific Area Command, from South Pacific to Pacific Fleet. By July 6th, officers at Pearl Harbor were reading about Evan Evans and Battery C. But while the reports were being written, the Japanese were making decisions of their own. On July 5th, Rabal sent six bombers to attack Renova.

Only six. They came in at night, high altitude, dropped their bombs from 20,000 ft, missed the island completely. The 90mm guns fired 37 rounds and claimed two hits. The remaining bombers turned back before reaching the target. On July 6th, the Japanese tried again. Four bombers. Same result. High altitude, night attack. No hits on the island. One bomber shot down.

The pattern was clear. The Japanese had learned. Daylight raids on Renova were suicide. The radar directed anti-aircraft fire was too accurate, too deadly. If they wanted to attack American positions in the New Georgia Group, they’d have to find another way. By July 10th, Japanese air raids on Renova had stopped almost entirely.

One attack on July 20th, six planes. Another on August 1st, six planes. Both high alitude raids that accomplished nothing. The Japanese had effectively conceded the airspace over Renova to American anti-aircraft guns. The 9inth Defense Battalion success had strategic consequences. With Renova secure, the 155mm long tom artillery batteries could fire without interruption. They pounded Japanese positions on New Georgia across Blanch channel 24 hours a day.

The big guns made the American advance on Munda airfield possible. Munda fell on August 5th. The airfield that had been the primary Japanese air base in the central Solomons was now in American hands. Marine and Army engineers had it operational within 72 hours. American fighters were flying missions from Munda by August 14th.

The campaign that had started with the Renova landings on June 30th was over in 5 weeks. The 9th Defense Battalion moved to New Georgia in October to defend the newly captured airfield. They set up their guns around Munda and waited for Japanese counterattacks. The attacks never came. The Japanese had abandoned the central Solomons. They were falling back to Buganville. The momentum had shifted.

The Americans were advancing. The Japanese were retreating. Evans and his crew spent 6 months on New Georgia. They fired their 90mm gun at occasional reconnaissance aircraft. They shot down three more planes, but nothing compared to July 4th. That day remained unique. The day when everything worked, when the radar locked on.

When the shells found their targets. When 12 Japanese bombers fell from the sky in 27 minutes. The official Marine Corps history would later call it one of the most successful anti-aircraft engagements of the Pacific War. The guns had performed beyond expectations. The crews had executed flawlessly. The Japanese had been stopped cold. But there was a cost.

A cost that didn’t show up in the kill reports or the afteraction summaries. A cost that Evan Evans and every other gun crew member would carry for the rest of their lives. Because shooting down 12 bombers meant killing more than 100 Japanese air crew. And some of those men had survived the crashes. Some had parachuted into the ocean.

Some had struggled in the water while American ships steamed past without stopping. War had rules, but sometimes the rules didn’t matter. Sometimes survival meant watching men drown. And sometimes heroes had to live with what they’ done to stay alive. The 9inth Defense Battalion remained on New Georgia until March 1944.

They defended Munda airfield against attacks that never materialized. The Japanese had moved their bombers north to Rabbal. They were conserving aircraft for the defense of the Marianas. The Central Solomons had become a backwater. Evans was promoted to corporal in October 1943. Boon made corporal in December. Gamberowski stayed private first class until January 1944.

The promotions came with citations, official recognition for their actions on July 4th, but no medals. Defense battalion personnel rarely received medals for anti-aircraft work. Shooting down planes was considered routine duty. In April 1944, the battalion shipped to the Russell Islands for rest and retraining.

6 months of combat had worn down men and equipment. The 90mm guns needed barrel replacements. Fire control systems needed recalibration. The Marines needed time away from the gun positions. They got 6 weeks. Then new orders arrived. The battalion was going to Guam. The landing on Guam began July 21st, 1944. The 9inth Defense Battalion came ashore at Agot on the first day.

They set up their anti-aircraft guns around the beach head. Their mission was air defense and perimeter security. The Japanese had fortified Guam heavily. The island had been in Japanese hands since December 1941. 22,000 Japanese troops were dug into the jungle and limestone caves. The battle for Guam lasted 3 weeks.

The 9inth Defense Battalion fired their guns at Japanese aircraft and ground targets. They shot down four more planes. They used their 90mm guns in direct fire mode against Japanese positions on the northern cliffs. High explosive shells proved effective against fortified bunkers. But the real enemy on Guam wasn’t the Japanese. It was deni fever.

The disease swept through the battalion in August. Hundreds of Marines fell ill. High fever, joint pain, exhaustion. Denge wasn’t fatal, but it was incapacitating. Men who could fight through enemy fire couldn’t function with deni. Evans caught it in mid August. He spent two weeks in a field hospital, lost 20 lb.

When he returned to duty, the battle for Guam was over. The Japanese had retreated to the northern cliffs. Thousands committed suicide by jumping rather than surrendering. The 9inth Defense Battalion stayed on Guam for the rest of the war. They defended Appa Harbor and the newly built airfield. American B29 Superfortresses were flying bombing missions against Japan from Guam by October 1944.

The Ninth’s job was to protect them. The Japanese launched occasional air raids, small formations, four or five planes, night attacks mostly. The 9inth Defense Battalion shot down six more aircraft between September 1944 and March 1945. Their total for the war reached 46 confirmed kills.

46 Japanese aircraft destroyed by one Marine Defense Battalion. July 4th, 1943 remained their best day. 12 kills in one engagement. No American anti-aircraft unit in the Pacific ever matched that record. Evans was on Guam when the war ended in August 1945. He was a sergeant by then, 24 years old, three years in the Marines, two Pacific campaigns, 46 enemy aircraft shot down by his battalion, 12 of them on one morning when everything worked perfectly. The 9inth Defense Battalion returned to the United States in February 1946.

They sailed into San Diego Harbor on the 23rd. The battalion was deactivated on March 1st at Camp Lune, North Carolina. The Marines went home back to Indiana, back to Michigan, back to lives interrupted by war. Evans returned to Richmond, Indiana. He’d left as a 21-year-old private.

He came back as a decorated sergeant, but Richmond was the same. The war had changed Evans more than Evans had changed Richmond. He reinlisted in 1948, served through the Korean War, made staff sergeant, left the Marine Corps in 1953, 11 years of service, two wars. He worked as a machinist after that. Married, had children, lived a quiet life. But he never forgot July 4th, 1943.

The day the planes fell. The day Suicide Point became a graveyard. The day 88 shells killed 12 bombers and changed the mathematics of air defense in the Pacific. He never talked about it much. Most veterans didn’t. The ones who’d been there knew what happened. The ones who hadn’t been there wouldn’t understand.

So Evans kept it quiet, worked his job, raised his family, lived his life until 1993, 50 years after Renova, when a Marine Corps researcher found the photograph in the National Archives and tracked down the men in the picture. Evans was 72 years old. He thought everyone had forgotten. He was wrong. In 1993, Alan Walker was an archivist at the National Archives in College Park, Maryland. He received a letter from a veteran named Evan Evans.

The letter was simple. Evans was looking for a photograph of a 90mm anti-aircraft gun. Any photo would do. He wanted to show his grandchildren what the gun looked like. Walker spent half a day searching. He found plenty of photos of the M1 gun. But something about the letter stayed with him.

He read it again. Evans mentioned Renova, mentioned July 4th, 1943. mentioned setting a record for shooting down Japanese bombers. Walker went back to the archives. This time he searched under Renova series 127GW. Combat photographs from the New Georgia campaign. He found it on the fourth page. Three Marines standing beside a 90mm gun. The caption identified them.

Private First Class Evan Evans, 22, Richmond, Indiana. Private Roy E. Boone, Indianapolis, Indiana. Private First Class John S. Gimberski, 20 Sagen, Michigan. This is one of the anti-aircraft guns which wiped out a Japanese bomber fleet of 12 planes in a single day at Renova Island. Walker sent the photograph to Evans.

The response came 2 weeks later. Evans had never known the photo existed. He’d never expected anyone remembered. Seeing himself at 22 years old, standing beside the gun that had made history, brought back 50 years of memories he tried to forget. He wrote Walker a letter thanking him. Said it meant more than Walker could know. Said he’d carried Renova with him every day for five decades.

Said maybe now he could let some of it go. Evans died in 2004 at age 83. Boone had died in 1998. Gamberowski passed in 2006. The gun crew that had made history on July 4th, 1943 was gone. But the story survived. The photograph survived. The official record survived. The 9inth Defense Battalion’s achievement at Renova became part of Marine Corps history.

Part of the larger story of how American forces learned to defeat Japanese air power in the Pacific. The lessons from Renova spread throughout the theater. Radar directed anti-aircraft fire became standard procedure. Gun crews trained on the integration techniques the 9inth defense battalion had pioneered.

The kill ratios improved across the board. Japanese bombers faced increasingly deadly defensive fire at every American position. By 1944, Japanese daylight bombing raids had become rare. By 1945, they’d stopped almost entirely. The Japanese couldn’t replace their losses fast enough, couldn’t train new crews fast enough.

The mathematics that Evan Evans and Battery C had demonstrated on July 4th, 1943 had scaled across the entire Pacific. 12 bombers shot down in 27 minutes, 88 shells fired, 90% destruction rate. Those numbers prove that American technology and American marines could defeat Japanese air attacks.

That suicide point could become a killing ground for the enemy instead of Americans. The beach at Renova is quiet now. The guns are gone. The bunkers have collapsed. The jungle has reclaimed most of the positions where the 9inth Defense Battalion fought. But on July 4th every year, a few people remember. Remember the day the planes fell. Remember Evan Evans and Roy Boon and John Gamberowski.

Remember that three young Marines changed the course of air defense in the Pacific. If this story moved you the way it moved us, do me a favor, hit that like button. Every single like tells YouTube to show this story to more people. Hit subscribe and turn on notifications. We’re rescuing forgotten stories from dusty archives every single day.

Stories about gunners and radar operators and Marines who held the line with precision and courage. Real people, real heroism. Drop a comment right now and tell us where you’re watching from. Are you watching from the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, Australia? Our community stretches across the entire world. You’re not just a viewer. You’re part of keeping these memories alive.

Tell us your location. Tell us if someone in your family served. Just let us know you’re here. Thank you for watching and thank you for making sure Evan Evans and his crew don’t disappear into silence. These Marines deserve to be remembered, and you’re helping make that

News

How One Woman’s Torn Typewriter Ribbon Saved 3,000 Lives and Sank 4 Japanese Carriers in 5 Hours

How One Woman’s Torn Typewriter Ribbon Saved 3,000 Lives and Sank 4 Japanese Carriers in 5 Hours At 4:17…

Elderly Couple VANISHED on Road Trip — 35 Years Later a Metal Detector Reveals the Horrifying Truth

Elderly Couple VANISHED on Road Trip — 35 Years Later a Metal Detector Reveals the Horrifying Truth On a…

Navy SEAL Asked The Old Man’s Call Sign at a Bar — “THE REAPER” Turned the Whole Bar Dead Silent

Navy SEAL Asked The Old Man’s Call Sign at a Bar — “THE REAPER” Turned the Whole Bar Dead Silent…

How One Girl’s “CRAZY” Trick Broke ENIGMA and Sank 5 Warships in 1 Night – Took Down 2,303 Italians

How One Girl’s “CRAZY” Trick Broke ENIGMA and Sank 5 Warships in 1 Night – Took Down 2,303 Italians …

The “Texas Farmer” Who Destroyed 258 German Tanks in 81 Days — All With the Same 4-Man Crew

The “Texas Farmer” Who Destroyed 258 German Tanks in 81 Days — All With the Same 4-Man Crew The…

German Pilots Couldn’t Believe B-17s With 16 Guns — Until These “Flying Fortresses” Fell Behind

German Pilots Couldn’t Believe B-17s With 16 Guns — Until These “Flying Fortresses” Fell Behind At 11:47 a.m. on…

End of content

No more pages to load