In the winter of 1876, deep in the isolated mountains of Montana territory, a German doctor named Theodore Brennan made a discovery that would haunt him for the rest of his life. Inside a remote cabin 23 mi from the nearest settlement, he found medical records that documented five generations of deliberate inbreeding within a single Irish family.

But that wasn’t the most disturbing part. Hidden beneath floorboards wrapped in oiled cloth were the preserved remains of seven infants, all bearing identical deformities that marked them as unworthy of life according to their own parents. The Donnelly family had been practicing selective infanticide for over a century, eliminating any child born with visible genetic defects to maintain their carefully constructed facade of normaly. What Dr.

Brennan discovered next would challenge everything the medical community believed about heredity, family bonds, and the lengths people would go to protect their bloodlines dark secrets. The evidence he uncovered suggested that this wasn’t an isolated case of frontier madness, but part of a deliberate genetic experiment that had been refined and perfected across generations, spanning two continents and nearly a 100red years of carefully concealed family practices.

Stories that reveal the darkest corners of American history. The story doctor Brennan would later document in his private journals began not in Montana’s unforgiving wilderness, but in the rolling green hills of County Cork, Ireland, where the Donnelly bloodline first took its twisted turn toward genetic catastrophe during the harsh winter of 1798……….![]()

![]()

![]()

In the winter of 1876, deep in the isolated mountains of Montana territory, a German doctor named Theodore Brennan made a discovery that would haunt him for the rest of his life. Inside a remote cabin 23 mi from the nearest settlement, he found medical records that documented five generations of deliberate inbreeding within a single Irish family.

But that wasn’t the most disturbing part. Hidden beneath floorboards wrapped in oiled cloth were the preserved remains of seven infants, all bearing identical deformities that marked them as unworthy of life according to their own parents. The Donnelly family had been practicing selective infanticide for over a century, eliminating any child born with visible genetic defects to maintain their carefully constructed facade of normaly. What Dr.

Brennan discovered next would challenge everything the medical community believed about heredity, family bonds, and the lengths people would go to protect their bloodlines dark secrets. The evidence he uncovered suggested that this wasn’t an isolated case of frontier madness, but part of a deliberate genetic experiment that had been refined and perfected across generations, spanning two continents and nearly a 100red years of carefully concealed family practices.

Stories that reveal the darkest corners of American history. The story doctor Brennan would later document in his private journals began not in Montana’s unforgiving wilderness, but in the rolling green hills of County Cork, Ireland, where the Donnelly bloodline first took its twisted turn toward genetic catastrophe during the harsh winter of 1798.

The Montana territory of 1874 represented the very edge of American civilization, a land where federal authority existed more in theory than practice. Helena, the territorial capital, boasted barely 8,000 souls clustered around the mining operations that had sparked the region’s growth. The surrounding mountains held only scattered mining camps, isolated homesteads, and native tribes, still actively resisting the encroachment of white settlers.

It was a landscape carved by violence and shaped by desperation, where families could

disappear for months without anyone asking questions, where the harsh winters claimed lives regularly, and where the territorial government’s reach extended only as far as its scattered deputies could ride through treacherous mountain passes.

The gold rush that had initially drawn settlers to Montana was beginning to wne by 1874, leaving behind abandoned claims and desperate men willing to try anything for survival. Supply lines stretched thin across hundreds of miles of wilderness, making even basic necessities scarce and expensive. Medical care was virtually non-existent outside Helena. And even there it consisted mainly of army surgeons and self-taught frontier doctors whose knowledge was limited to treating gunshot wounds and setting broken bones.

It was precisely this isolation and lack of oversight that made Montana territory attractive to certain types of settlers, those who needed to disappear from civilized society and its inconvenient questions. Into this unforgiving landscape came Patrick Donnelly and his wife Bridg along with their four surviving children. Sheamus age 19, Moira 17, Colleen, 15, and young Declan barely 12.

They arrived in Helena on a freight wagon in September 1874. Their possessions carefully packed in wooden crates that suggested wealth unusual for typical Irish immigrants. Patrick presented himself as a successful potato farmer, fleeing the lingering effects of the Irish famine, but his hands showed none of the calluses typical of agricultural work.

Instead, his fingers bore the ink stains of a man accustomed to recordkeeping, and his speech carried the educated accent of someone who had received formal schooling, rare luxuries for an Irish peasant of that era. Bridg Donnelly struck observers as a woman perpetually on the edge of nervous collapse. Smallboned and prematurely aged, she rarely spoke above a whisper, and kept her children close with an intensity that bordered on obsession.

Local merchants noted that she paid for supplies exclusively in gold coins, counting each one multiple times before reluctantly parting with it. Her eyes held a haunted quality that suggested she had witnessed horrors that went far beyond the typical hardships of frontier life.

What the territorial land office didn’t know was that the Donnies carried elaborately falsified papers from New York claiming residents in Brooklyn for 3 years prior to their westward journey. The documents were expertly forged, complete with fake employment records and fabricated references that would have fooled all but the most thorough investigation. In reality, they had never lived in New York.

They had fled directly from Ireland after a scandal that had shaken their rural community to its core. a scandal that involved the local parish priest discovering what he called an abomination against God and nature within their extended family. Father Michael O Sullivan, a man known for his discretion regarding parishioners private struggles, had become so horrified by what he discovered about the Donnelly family practices that he threatened immediate excommunication and exposure to British authorities. The priest’s usually steady hand had

trembled as he wrote his final warning to Patrick Donnelly. What you have done in the name of bloodline purity is a sin that cries out to heaven for vengeance. Leave this parish immediately or I will ensure that every soul in County Cork knows the true nature of your family’s abominations. Patrick had purchased 160 acres of remote mountain land from the territorial government, paying in gold coins that raised no suspicions in a territory where such currency was common among former miners and prospectors. The land sat in a narrow valley between two

steep ridges accessible only by a treacherous mountain trail that became completely impassible during the worst winter months. The isolation was so complete that smoke from their cabin chimney couldn’t be seen from any neighboring homestead, and the nearest water source, a spring-fed creek, flowed only during the brief summer months before freezing solid for nearly half the year.

The location was perfect for a family that desperately needed to hide from the world. But it also presented challenges that would test even their carefully planned survival strategies. The growing season at that altitude lasted barely 4 months, requiring intensive agricultural knowledge to produce enough food for winter survival.

The extreme cold could kill livestock in a single night if proper precautions weren’t taken. And the psychological pressure of complete isolation for 6 months of every year had driven many frontier families to madness or suicide. Yet the Donnies built their homestead with the efficiency of people who had faced similar challenges before.

Patrick and his sons constructed a sturdy log cabin with thick walls designed to retain heat, small windows that minimized heat loss, and a complex system of interior partitions that could be sealed off during the coldest weather.

The construction showed knowledge of building techniques that went beyond typical frontier skills, suggesting either previous experience with extreme climates or consultation with experts before their arrival in Montana. Bridg and the girls prepared for their first Montana winter with methodical precision that impressed even experienced mountain dwellers. They preserved meat using techniques that maximized storage space and minimized spoilage.

cultivated crops specifically chosen for their ability to grow in short seasons and poor soil and established systems for rationing supplies that showed mathematical precision unusual for supposedly uneducated Irish peasants. But neighbors who occasionally encountered them during supply runs to Helina noted peculiarities that set the Donnies apart from other frontier families.

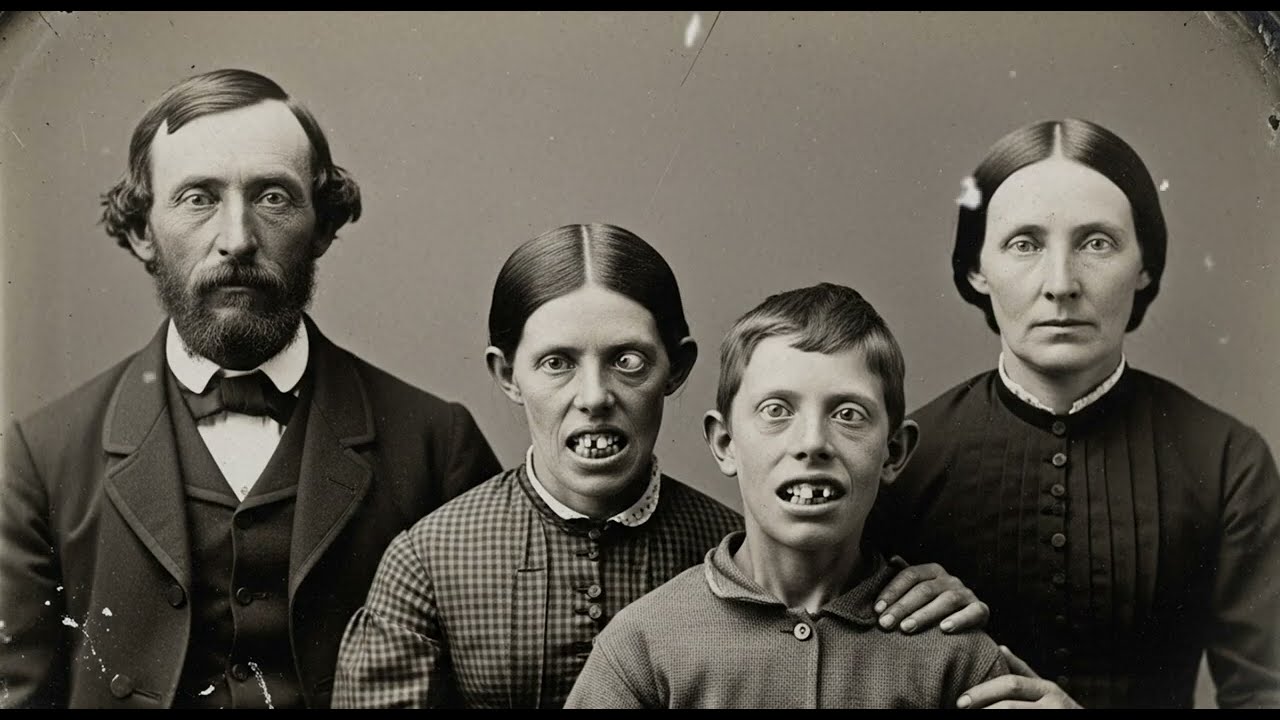

The family members bore striking resemblances to one another that went far beyond normal family traits. Their pale blue eyes, sharp angular features, and unusually long fingers created an almost uncanny uniformity of appearance. The children displayed behavioral patterns that seemed simultaneously advanced and disturbing.

They showed remarkable intelligence and self-discipline for their ages, but also a weariness around strangers and an submissiveness to parental authority that suggested fear rather than respect. Most unsettling were the conversations overheard by Jake Harrison, the territorial male carrier who made monthly runs through the mountain settlements.

The family spoke frequently in Irish Gaelic, but even when using English, their discussions contained references to maintaining the purity of the line, the strength that comes from proper breeding, and the sacrifices necessary for family advancement. These weren’t the typical concerns of frontier families struggling for basic survival. They suggested deeper, more disturbing motivations for their isolated lifestyle.

The first sign that something was deeply wrong with the Donnelly family emerged in March 1875 when the spring Thor finally opened the mountain passes after 6 months of complete isolation. Jake Harrison, making his first mail run since the previous October, arrived at their cabin to deliver government correspondents and immediately sensed that something terrible had happened during the long winter months.

The cabin itself showed signs of recent alterations. New boards covered what appeared to be holes in the walls, fresh chinking filled gaps that suggested violence or struggle, and the area around the building bore evidence of significant digging despite the frozen ground.

Most disturbing was the smell that permeated the entire homestead, a sickly sweet odor that Harrison recognized from his years of frontier experience as the lingering scent of death and decay. Bridg Donnelly met him at the door. Her appearance so dramatically changed that Harrison initially didn’t recognize her. The woman who had arrived in Montana just 6 months earlier as a nervous but relatively healthy frontier wife now looked haggarded and holloweyed, her hands trembling with what appeared to be chronic anxiety.

Her clothing hung loose on a frame that had lost significant weight, and her hair had gone prematurely gray at the temples. When she attempted to speak, her voice cracked as if she hadn’t used it in weeks. The winter was difficult,” she managed to whisper, glancing nervously toward the cabin’s interior. “We lost. We had complications.

” Harrison found the family in the midst of what appeared to be a difficult birth with Bridg in active labor attended only by her teenage daughter, Moira. But what he witnessed during that March afternoon would later become crucial evidence in understanding the family’s dark history. The scene was orchestrated with a clinical precision that suggested extensive previous experience with similar situations. The infant that emerged was clearly malformed.

Its spine curved in an unnatural S shape, its left arm ending in a clubed hand with only three fingers, and its head disproportionately large with a pronounced sloping forehead that indicated severe developmental abnormalities. The child’s breathing was labored, and its cries had a weak muing quality that suggested internal complications beyond the visible deformities.

But what disturbed Harrison most was the family’s reaction to this obviously suffering infant. Rather than the grief, concern, or frantic efforts to help that he expected from parents facing such a tragedy, he observed what he later described as cold, calculated assessment in their eyes. Patrick and Bridg exchanged meaningful glances while speaking to each other in rapid Irish Gaelic that Harrison couldn’t understand.

Their tone suggested not surprise or anguish, but rather discussion of predetermined procedures for handling a familiar situation. “The child won’t survive the weak,” Patrick announced with clinical detachment, though the infant’s breathing appeared relatively strong, and its cries, while weak, suggested basic vitality. “The mountain air is too harsh for one so delicate.

It’s God’s mercy, really, better to take them young than let them suffer.” Harrison offered to ride immediately to Helena for a doctor, emphasizing that even severely deformed infants sometimes survived with proper medical care, but Patrick firmly refused. His pale blue eyes growing hard with an authority that borked no argument.

“We know how to handle our own troubles,” he said, placing a possessive hand on his wife’s shoulder. “It’s the Lord’s will that some children aren’t meant for this world. interfering with divine judgment would be a sin against nature itself. The religious justification struck Harrison as rehearsed as if Patrick had delivered similar explanations many times before.

There was also an underlying threat in his tone that suggested serious consequences for anyone who might interfere with the family’s private handling of the situation. Sheamus and young Declan, who had been working outside during the birth, returned to the cabin with expressions that showed no surprise at finding their mother in labor or their newest sibling obviously deformed, suggesting this wasn’t the first such birth they had witnessed.

When Harrison returned 2 weeks later with routine male delivery, the infant was gone. Bridg met him at the door with red- rimmed but completely dry eyes. The look of someone who had exhausted their capacity for grief rather than someone experiencing fresh loss. Lost the baby 3 days after you left,” she reported in a voice devoid of emotion. “Buried him behind the cabin next to the others.

” “The weak don’t survive out here, and it’s better that way.” Her phrase, “Next to the others,” sent chills through Harrison’s spine. Behind the cabin, he now noticed for the first time stood a row of small wooden crosses marking fresh turned earth. He counted four graves, all too small for adult burials, all marked with crude dates spanning the past 8 months.

The implications were staggering. The Donnies had lost multiple infants during their first year in Montana, losses that had never been reported to territorial authorities as required by law. The graves themselves looked wrong to Harrison’s experienced eye.

The dirt was disturbed in a pattern that suggested hasty, panicked work rather than the careful burial of beloved children. The crosses were uniform in size and construction, as if made in advance rather than crafted individually for each loss, and the spacing between graves suggested systematic planning rather than random tragedy. They were arranged in a neat row that left space for additional burials.

That summer, as Harrison continued his monthly mail runs, he began paying careful attention to the Donnelly family dynamics. What he observed gradually painted a picture of a household operating under rules and pressures that had nothing to do with typical frontier survival. The children moved with the careful precision of people who knew that mistakes carried severe consequences, and their interactions with each other showed patterns of communication that suggested shared knowledge of family secrets too dangerous to discuss openly. Moira and Colleen, despite being only 17 and 15,

carried themselves with the knowledge and weariness of much older women. They handled domestic tasks with efficiency that went beyond normal teenage competence. But their eyes held a haunted quality that suggested they had witnessed things that fundamentally changed their understanding of family relationships.

When they spoke to their parents, their voices carried a difference that seemed rooted in fear rather than respect. Sheamus, the eldest son at 19, had developed a pronounced stutter that seemed to worsen whenever his father was present. He flinched at sudden movements and avoided eye contact with anyone outside the immediate family.

Most disturbing was his reaction to questions about family life. He would begin to respond normally, then catch himself and fall silent as if remembering consequences for revealing family information. Young Declan appeared the most normal of the children, but Harrison caught him once staring at the small cemetery behind the cabin with an expression of terror rather than sadness.

When asked about his deceased siblings, the boy had responded, “Sometimes babies aren’t right, and father says God doesn’t want them to suffer, but sometimes I think I think maybe God didn’t decide.” The child had immediately clapped his hand over his mouth as if realizing he had said something forbidden and refused to speak another word during Harrison’s entire visit.

Most disturbing were the conversations Harrison sometimes overheard when approaching the cabin quietly through the forest. The family spoke frequently about keeping the line pure, maintaining the strength of the blood, and the sacrifices our ancestors made to preserve what matters. They used Irish phrases that Harrison couldn’t translate, but the tone suggested rituals or traditions that went far beyond normal family customs.

There were references to the others back home, what happened to the weak ones, and most chillingly, discussions of which children show the signs and how to handle the imperfect ones. These conversations painted a picture of a family operating according to beliefs and practices that predated their arrival in Montana by many years, possibly generations.

The isolated mountain homestead wasn’t just a refuge from civilization. It was a carefully chosen location where the family could continue traditions that would be impossible to maintain under the scrutiny of normal community life. As 1875 progressed into its harsh winter months, the Donnelly family’s isolation became complete once again.

Snow blocked the mountain passes from November through March, cutting them off entirely from the outside world for the second time since their arrival in Montana territory. But it was during this second period of isolation that the true nature of their genetic legacy began to manifest in ways that would eventually draw the attention of territorial authorities and shock even the frontier’s hardened residents.

Doctor Theodore Brennan, the territorial physician who would later investigate the family, had arrived in Helena in October 1875, carrying with him medical texts and knowledge that represented the cutting edge of hereditary science.

A graduate of the University of Vienna with additional training in Berlin and Edinburgh, Brennan had studied under physicians who were just beginning to understand the mechanisms of genetic inheritance. His medical library contained works by Francis Golton and other pioneers of what would later become known as genetics, giving him knowledge that wouldn’t become common medical understanding for decades to come.

Brennan had come to Montana territory not for adventure or profit, but to escape a professional scandal in Europe. His research into hereditary traits had led him to conclusions about human breeding that his colleagues found disturbing and his vocal support for controlled reproduction to improve the human species had made him persona non grata in respectable medical circles.

The frontier offered him anonymity and the freedom to pursue his scientific interests without institutional oversight. Ironically, the same freedom that had attracted the Donnelly family for their own disturbing purposes. During the winter of 1875, 1876, Brennan received his first hint that something was seriously a miss in the mountain valleys when Jake Harrison arrived at his Helena office in February.

Having risked the dangerous winter trail to seek medical consultation, Harrison described phenomena that defied his eight years of experience in the Montana wilderness. Strange lights seen coming from the Donnelly cabin at odd hours of the night, smoke patterns that suggested fires being burned at unusual times and temperatures, and most disturbing of all, sounds that carried across the frozen landscape during the still winter nights. Doctor,” Harrison said, his weathered face creased with worry and confusion.

“I’ve been carrying mail through these mountains for 8 years. I know the difference between normal frontier hardship and something genuinely wrong. What I’m hearing from that cabin in the dead of winter, it’s not the sound of people dealing with ordinary troubles. There’s crying that goes on for hours, then stops so suddenly it’s like someone threw a switch.

And there’s singing, if you can call it that, that doesn’t sound quite human. The melody is wrong, like it’s meant for voices that don’t work the same way ours do. Harrison also reported visual phenomena that troubled his practical frontier sensibilities. The Donnelly cabin showed lights burning at times when fuel conservation should have been critical for winter survival.

The patterns of illumination suggested activities requiring sustained light during the darkest hours of night. activities that didn’t match normal family routines. Most disturbing were the occasions when Harrison glimpsed figures moving outside the cabin during blizzard conditions that should have made outdoor activity impossible.

Figures that seemed unusually tall or moved with gates that didn’t look entirely human in the shifting snow and shadows. Brennan’s medical instincts were immediately aroused by Harrison’s descriptions, but the winter weather made any journey to the Donnelly homestead absolutely impossible. The mountain passes were blocked by snow depths that made travel suicidal, and even if he could have reached the cabin, winter emergency visits were typically requested only for life-threatening situations that couldn’t wait for spring. The Donnelly family had never

requested medical assistance despite the obvious health problems Harrison had described. Instead of attempting a dangerous winter journey, Brennan began researching Irish immigration records and territorial archives, looking for any available information about the family’s background and previous medical history.

What he discovered raised more questions than answers and painted a picture of systematic deception that suggested the family’s problems went far deeper than simple frontier hardship. The Donnies had claimed to be from County Cork, Ireland, fleeing poverty and crop failures that affected rural Irish communities throughout the 1860s and early 1870s.

Their immigration papers contained detailed stories about lost relatives, destroyed farms, and economic circumstances that forced them to seek opportunities in America. But careful cross-referencing of their claims with official Irish parish records revealed inconsistencies that strongly suggested elaborate falsification.

The listed relatives in Ireland couldn’t be verified through church baptismal and marriage records that normally provided reliable genealogical information. The described farm locations didn’t match existing land ownership records from County Cork. Most troubling, the stated reasons for immigration, crop failures, and poverty didn’t match the significant amount of gold the family had used to purchase their Montana property, pay for transcontinental transportation, and establish their isolated homestead.

More disturbing were reports Brennan found buried in New York immigration files, documents that immigration officials had apparently failed to follow up properly. A family named Donnelly had indeed passed through Ellis Island in 1874, but they had been flagged by medical inspectors for concerning physical characteristics among the children that suggested possible genetic abnormalities.

The medical report described signs of developmental irregularities consistent with hereditary defects and noted that the parents had become increasingly aggressive and evasive when questioned about their family medical history. The immigration medical inspector, Dr.

Samuel Morrison had recommended that the family be detained for extended medical evaluation, but his report had been overruled by administrative officials eager to process the large numbers of immigrants passing through Ellis Island daily. Morrison’s notes suggested that his concerns went beyond simple medical abnormalities.

He had observed behavioral patterns in the family that suggested systematic concealment of information relevant to public health and safety. As Brennan delved deeper into available records, he discovered references to Irish families named Donnelly in other American communities. Families that had arrived at different times, but showed similar patterns of behavior.

A Donnelly family in Pennsylvania had attracted attention from local authorities in 1871 for unusually high infant mortality rates. Another Donnelly family in Ohio had been investigated by county officials in 1873 for possible child neglect, though the investigation had been dropped when the family suddenly relocated without leaving forwarding information.

The pattern suggested that the Montana Donnies weren’t isolated criminals, but part of a larger network of related families who shared similar practices and moved frequently to avoid official scrutiny. The implications were staggering. If these were all branches of the same extended family, their genetic manipulation and systematic infanticide might have been practiced across multiple states and involved dozens of victims over many years. As spring approached and the mountain passes began to clear, Brennan found

himself increasingly obsessed with the mystery of the Donnelly family. His professional training told him that isolated populations often developed genetic problems due to limited breeding pools, a wellocumented phenomenon in remote communities throughout history. But something about this particular family suggested a pattern far more deliberate and systematic than simple geographic isolation could explain.

The combination of Harrison’s disturbing observations, the suspicious immigration records, and the evidence of possible connections to similar families in other states convinced Brennan that the Donnies represented something unprecedented in his medical experience. a family that had deliberately chosen to pursue genetic experimentation on themselves regardless of the consequences for their children or the broader community.

When the spring Thor of 1876 finally opened the mountain trails, Dr. Brennan made the decision to visit the Donnelly homestead personally, ostensibly to provide routine medical services to an isolated frontier family. What he found there would fundamentally change his understanding of human nature, genetic science, and the length to which people would go to preserve family secrets that spanned multiple generations.

The journey to the Donnelly cabin required a full day of difficult travel through terrain that seemed deliberately chosen for its inaccessibility. The trail wound through dense forests, across unstable creek beds and up steep mountain slopes that would have challenged even experienced horsemen.

The isolation was so complete that Brennan encountered no other travelers, no signs of other homesteads, and no evidence that anyone else had used the trail in months. The cabin itself appeared deceptively normal from the outside, well-built, well-maintained, with signs of careful farming and successful animal husbandry that suggested a family adapting well to frontier life.

The immediate surroundings showed evidence of hard work and intelligent land use, carefully tended vegetable gardens, efficient livestock shelters, and water management systems that demonstrated sophisticated agricultural knowledge. But Brennan’s medically trained eye immediately noticed troubling details that most visitors would have overlooked.

The family cemetery behind the cabin contained far too many graves for a family that claimed to have lost only occasional infants to the harsh frontier conditions. Brennan counted 11 wooden crosses, all marking plots that were clearly too small for adult burials, all carved with dates that showed deaths occurring at suspiciously regular intervals rather than the random clustering typical of epidemic disease or severe weather casualties.

The graves themselves were arranged in neat rows that suggested systematic planning rather than desperate responses to unexpected tragedies. More disturbing was the evidence of recent expansion in the cemetery area. Fresh tool marks in the surrounding trees and recently moved earth suggested that additional grave sites were being prepared in advance. Preparations that implied the family expected future deaths rather than hoping to avoid them.

The crosses marking existing graves showed similar construction and weathering patterns as if they had been made in batches rather than individually crafted for each deceased child. Patrick Donnelly met him at the cabin door with a mixture of frontier hospitality and barely concealed weariness that immediately set Brennan’s professional instincts on edge.

The family patriarch had aged dramatically since Harrison’s descriptions from the previous year. His hair had gone completely white despite his apparent age of 45, and deep lines creased his face in patterns that suggested chronic stress rather than normal aging. His hands trembled slightly when he thought no one was watching, and his eyes held a haunted quality that Brennan recognized from patients suffering from severe psychological trauma.

“We don’t need a doctor here,” Patrick said with forced firmness. But his voice carried less conviction than his words suggested. We’ve always handled our own troubles, just as our families did in the old country. Bringing outsiders into family matters only complicate situations that are better resolved through traditional methods. Bridg appeared behind her husband, and Brennan was shocked by the extent of her physical deterioration since Harrison’s previous descriptions. The woman who had given birth just over a year earlier now looked gaunt and holloweyed. Her frame

so thin that her clothing hung like drapes over protruding bones. Her hands showed a constant tremor that could have indicated neurological problems, chronic malnutrition or psychological stress severe enough to cause physical symptoms.

When she attempted to speak, Patrick silenced her with a sharp look that suggested years of practiced dominance and consequences for disobedience that went beyond normal marital authority. But it was the children who provided the most disturbing evidence of the family’s dark secrets and abnormal lifestyle. Moira, now 18, was clearly pregnant again. her condition advanced enough to suggest conception during the isolated winter months when no outsiders could have been present.

The implications of this timing, combined with the family’s isolation and unusual genetic patterns, raised questions that Brennan found professionally and personally disturbing. Colleen, now 16, showed signs of premature physical development that seemed accelerated beyond her chronological age. Her adult features appeared fully formed in ways that suggested hormonal abnormalities, possibly related to genetic factors or environmental influences. More troubling was her behavior around her parents.

She displayed a combination of maturity and submissiveness that suggested experiences inappropriate for someone her age. Most disturbing was young Declan, now 13, who had developed pronounced physical abnormalities since Harrison’s previous visits. The boy’s facial features showed clear asymmetry, with one side of his face appearing normally developed, while the other showed signs of arrested growth or mal foration.

He walked with a pronounced limp that suggested spinal curvature, and his hands showed the elongated fingers and unusual joint flexibility that Brennan recognized as possible indicators of genetic connective tissue disorders. During his brief initial visit, Brennan observed family dynamics that defied normal social conventions and suggested psychological pressures that went far beyond typical frontier hardships.

The older children deferred to their parents with a combination of fear and resignation that indicated consequences for disobedience far more severe than normal parental discipline. Their movements were careful and calculated, as if they had learned through experience that spontaneous behavior could trigger unpredictable and dangerous responses. Sheamus, the eldest son at 20, avoided eye contact with both his parents and the visiting doctor.

His pronounced stutter had worsened to the point where he could barely communicate, and he seemed to be fighting some internal struggle that left him visibly agitated throughout Brennan’s visit. When asked direct questions about family life or his own health, Sheamus would begin to respond normally, then catch himself mid-sentence and fall silent, as if remembering severe consequences for revealing family information to outsiders.

The family’s living arrangements also struck Brennan as abnormal for typical frontier households. The cabin’s interior was divided into more separate spaces than necessary for privacy alone, with heavy curtains and locked doors that seemed designed to conceal activities rather than simply organize family life.

Sounds from other parts of the cabin suggested ongoing activities that the family didn’t want their visitor to observe. and there were smells, medicinal, organic, and vaguely disturbing, that implied practices beyond normal frontier medicine or food preservation. As Brennan prepared to leave after his initial assessment, Patrick pulled him aside with an urgency that bordered on desperation.

His manner suggested a man wrestling with competing desires to maintain family secrets and seek help for problems that had grown beyond his ability to manage alone. Doctor,” Patrick whispered, glancing nervously toward the cabin to ensure they weren’t overheard by family members. “If I were to tell you that sometimes, sometimes God tests families in ways that require terrible choices, would you understand what I mean? Would you be able to help without asking questions that might bring trouble to people who are already suffering?” Before Brennan could formulate a response, Patrick continued with

increasing agitation. Our bloodline carries great strength, but it also carries complications. We’ve learned to manage these complications through methods that our fathers and grandfathers developed over many generations. These methods have worked for us in the old country, but here in Montana, people ask different kinds of questions.

They expect things that we cannot provide without revealing practices that that wouldn’t be understood by those who don’t share our particular burdens. The implications of Patrick’s carefully worded confession sent chills through Brennan’s professional composure.

He was beginning to understand that the Donnelly family’s isolation wasn’t just about avoiding social scrutiny for unusual behavior. It was about hiding systematic practices that would horrify even the frontiers rough and tumble society. practices that had been refined and perfected over multiple generations before being transplanted to the American wilderness. Two months after his initial visit, Dr.

Brennan received an urgent message from Jay Harrison that would force him to confront the full horror of the Donnelly family’s genetic legacy. The message delivered by a local trapper who had risked the treacherous mountain trail contained only a few hastily scrolled words. Donnelly woman in bad labor.

family asking for doctor. Something wrong beyond normal birthing troubles. Come quick if you can. For the first time since their arrival in Montana territory, the Donnelly family was requesting outside medical assistance, a dramatic departure from their previous insistence on handling all family matters privately.

The fact that they had overcome their obsessive secrecy to ask for help suggested complications so severe that even their extensive experience with difficult births couldn’t provide adequate solutions. Brennan arrived at the mountain cabin on a sweltering July afternoon to find a scene that would haunt his nightmares for decades to come.

The oppressive heat had turned the isolated valley into a furnace, and the air hung thick with humidity that made breathing difficult even for healthy individuals. Inside the cabin, the atmosphere was even more stifling, heavy with the smells of sweat, blood, and something else. A sickly sweet odor that Brennan couldn’t immediately identify, but that triggered his instincts as deeply wrong.

Moira Donnelly lay in the cabin’s back room. her labor complicated by factors that became immediately apparent to Brennan’s trained eye. The young woman was giving birth to twins, but these weren’t ordinary multiple births. The infants were conjoined at the torso and appeared to share major internal organs, a condition that Brennan knew was almost always fatal in an era before advanced surgical intervention.

But what shocked him most wasn’t the medical complexity of the situation, but rather the family’s reaction to this obviously catastrophic development. Rather than the panic, grief, and desperate hope for divine intervention that he expected from parents facing such a tragedy, the Donnies displayed a cold, methodical response that suggested they had dealt with similar situations many times before.

Patrick and Bridg work together with the efficiency of people following a well-established protocol. Their movements coordinated and purposeful rather than frantic. Sheamus and Colleen prepared materials and instruments that clearly weren’t intended for celebrating a birth, but rather for managing a situation that required immediate and decisive action. The twins themselves presented a medical challenge that would have strained the resources of even the best equipped hospitals of the era.

They shared not only external tissue connections, but appeared to have integrated cardiovascular and nervous systems that made separation impossible with 1876 medical technology. One infant was clearly stronger than the other, but both showed signs of vitality that suggested they might survive for days or even weeks if provided with appropriate supportive care.

“Doctor,” Patrick said with clinical detachment that chilled Brennan’s blood. “We need you to tell us honestly whether they can be separated, whether there’s any medical procedure that might allow one of them to survive as a normal child.” As Brennan began his examination of the conjoined twins, he noticed something that made his blood run cold.

Hidden beneath the birthing bed were leatherbound journals filled with detailed drawings and notes documenting similar births over what appeared to be many decades. Page after page showed careful anatomical sketches of infants with various deformities, cleft pallets, missing limbs, spinal mal forations, extra digits, and conditions that Brennan had never seen illustrated with such clinical precision.

Each drawing was annotated with notes in Irish Gaelic and English dated entries that spanned several decades and multiple geographic locations. Some entries included detailed descriptions of remedial measures taken to address these genetic complications using terminology that suggested medical knowledge far beyond what typical frontier families would possess.

The dates and locations of the documented births created a pattern that traced the family’s movements across Ireland and America over more than 50 years. Most disturbing were the detailed anatomical studies that accompanied each birth record. The illustrations showed not just the external deformities, but also speculative internal anatomy, potential survival prospects, and what the notes euphemistically called quality of life assessments.

The clinical language couldn’t disguise the fact that these records documented systematic evaluation of newborn infants for traits that the family considered acceptable or unacceptable for survival. Bridg noticed his discovery and spoke for the first time since his arrival. Her voice carrying the weight of generations of terrible knowledge. The bloodline must be kept pure.

Doctor, weakness cannot be allowed to spread and contaminate future generations. Our families learned this truth through hard experience over many generations back in the old country. What looks like cruelty to outsiders is actually mercy. Both for the children who would suffer and for the family line that must be preserved.

Her words were delivered with the conviction of someone reciting fundamental religious doctrine. But the doctrine she described involved principles of human breeding that violated every standard of medical ethics and human decency that Brennan had learned during his professional training. The Donnelly family wasn’t just practicing infanticide. They were conducting systematic genetic experimentation on their own children using principles of selective breeding that treated human beings as livestock to be improved through careful culling of undesirable traits. The leather

journals contained additional evidence that revealed the true scope of the family’s genetic manipulation. Hidden within the medical records were genealological charts that traced the Donnelly bloodline through multiple generations, showing patterns of intermarriage between closely related family members that explained the high frequency of genetic abnormalities among their children.

The charts revealed that Patrick and Bridg weren’t just husband and wife. They were also first cousins, continuing a pattern of deliberate inbreeding that extended back through five generations of carefully planned marriages designed to concentrate what the family believed were superior genetic traits. The genealological documentation showed that the practice had begun in Ireland during the early 1800s when Patrick’s great-grandfather had become convinced that the Irish people could be improved through selective breeding similar to the

agricultural techniques used to develop superior livestock. The family had justified their systematic inbreeding through a twisted interpretation of biblical genealogies and pseudocientific theories about racial superiority that had gained popularity among certain educated classes in Europe during that era.

As Brennan continued examining the twins and studying the family’s medical records, he realized he was witnessing the culmination of a genetic experiment that had been conducted across multiple generations with complete disregard for the suffering it caused. The conjoined infants struggling for breath in their makeshift cradle represented not a random tragedy, but the inevitable result of decades of systematic genetic manipulation that had finally produced abnormalities too severe to be hidden or rationalized away. Just when we thought we’d seen it all, the horror in the Montana mountains

intensifies. If this story is giving you chills, share this video with a friend who loves dark mysteries. Hit that like button to support our content, and don’t forget to subscribe to never miss stories like this. Let’s discover together what happens next in this disturbing tale of genetic manipulation and family secrets that spans generations of deliberate human experimentation.

The immediate crisis of the conjoined twins forced Brennan to make decisions that would haunt his conscience for the rest of his career. The infants were clearly suffering. Their shared cardiovascular system struggling to support two separate bodies, their breathing labored and irregular.

Medical intervention was impossible with the primitive equipment available in the isolated mountain cabin. But allowing them to suffer without attempting some form of relief violated every principle of medical ethics that Brennan had sworn to uphold. As doctor, Brennan studied the hidden journals through the night while the conjoined twins fought for their lives.

The true scope of the Donnelly family’s genetic manipulation became terrifyingly clear. The records documented not just five generations of selective breeding and systematic infanticide, but a comprehensive program of human experimentation that had been practiced with scientific precision for over a century.

The oldest entries written in faded brown ink and archaic Irish script described how the original Donnelly patriarch Fergus Donnelly had begun the practice in County Cork during the 1790s after consulting with what the journal called learned men who understood the science of bloodlines and the improvement of human stock.

These early entries revealed that Fergus had been influenced by agricultural breeding theories that were becoming popular among progressive farmers of the era. Men who had achieved remarkable success in developing superior breeds of cattle, horses, and sheep through careful selection and controlled mating.

Fergus had become convinced that the same principles could be applied to human reproduction to create what he termed a perfected Irish bloodline that would be superior in intelligence, physical strength, and moral character to the degraded peasant stock that he believed had been weakened by centuries of British oppression and poverty. His initial experiments involved arranging marriages between his own children and their first cousins, justified through careful study of biblical genealogies that seemed to support the practice of close intermarriage within family

groups. The early results had seemed to support Fergus’s theories. The first generation of deliberately inbred children showed unusual intelligence, striking physical beauty, and what the family interpreted as evidence of genetic superiority. But the records also revealed that even in the first generation, there had been births of severely deformed infants that were quietly eliminated through what the journal euphemistically called merciful release from earthly suffering.

As the generations progressed, the genetic experimentation became increasingly systematic and scientifically sophisticated. Each subsequent patriarch had refined the breeding program, introducing new selection criteria and developing increasingly elaborate justifications for eliminating children who failed to meet the family’s evolving standards of genetic acceptability.

The journals contained detailed discussions of traits considered desirable. pale blue eyes, angular facial features, unusual height, mathematical aptitude, and traits that warranted immediate elimination, visible physical deformities, mental retardation, and what the family termed behavioral irregularities. But the most disturbing revelation came when Brennan discovered a section of the journal dedicated to what was called the enhancement protocol. The entries described systematic attempts to accelerate the concentration of desired

traits through increasingly close breeding relationships. Patrick’s generation represented the culmination of this process. He and Bridg were not just first cousins, but the products of four previous generations of deliberate inbreeding designed to maximize the expression of what the family considered superior genetic characteristics.

The protocol had achieved its intended results in some respects. The surviving Donnelly family members did indeed show remarkable intelligence, striking physical uniformity, and certain capabilities that set them apart from typical frontier families. But the genetic cost had been catastrophic. The high frequency of severe birth defects, the obvious mental health problems affecting the older children, and the progressive deterioration of the parents all indicated that the family’s genetic experiment had reached a point of crisis that threatened their survival as a

viable breeding population. My great-grandfather believed he was creating a superior race. Patrick confessed as Brennan confronted him with the evidence from the journals. He studied the breeding methods used by the finest horse and cattle breeders in Ireland, men who had created animals of exceptional quality through careful selection and controlled mating.

He believed that the Irish people had been degraded by centuries of poverty and oppression, and that only through deliberate improvement of our bloodlines could we reclaim our rightful position as a superior people. Patrick’s voice carried a mixture of pride and growing doubt as he continued. For four generations, the method seemed to work. Our family produced children of exceptional intelligence and beauty.

Men and women who could have been leaders and innovators if the world had been ready to recognize our superiority. But the cost, the cost has been terrible. So many children born wrong. So many who had to be released from lives that would have brought nothing but suffering to themselves and shame to the family line. The genetic reality that Brennan understood from his advanced medical training painted a far different picture than the family’s eugenic fantasies.

The Donnelly bloodline hadn’t been purified and improved through selective breeding. It had been systematically destroyed through the accumulation of recessive genetic traits that produced increasingly severe abnormalities with each generation.

The children who survived to adulthood carried hidden genetic damage that would inevitably be expressed in their own offspring, creating a downward spiral of genetic deterioration that could only end in the complete extinction of the family line. The conjoined twins struggling for breath in their makeshift cradle represented the ultimate failure of the Donnelly genetic experiment. Five generations of deliberate inbreeding had not created superior human beings.

It had produced increasingly severe deformities that could no longer be hidden, rationalized, or eliminated without arousing the suspicions of a society that was becoming less tolerant of isolated family practices that violated accepted moral and legal standards.

As Brennan watched Patrick and Bridgette prepare to carry out what they clearly saw as another necessary elimination of genetically unacceptable offspring, he realized he was witnessing the culmination of America’s first systematic experiment in human eugenics. An experiment that had been conducted in secret for over a century, leaving a trail of murdered infants and psychologically destroyed family members across two continents.

The immediate confrontation over the fate of the conjoined twins became a battle not just for the lives of two suffering infants, but for the soul of a family that had lost all sense of human decency in pursuit of genetic perfection that existed only in their own twisted imagination. The confrontation between Doctor Brennan and the Donnelly family over the fate of the conjoined twins marked the end of their centurylong genetic experiment and the beginning of a reckoning that would expose one of the darkest chapters in the intersection of family secrets, primitive genetic science, and the American frontiers tolerance for isolated communities

operating beyond the reach of civilized oversight. Brennan’s intervention, backed by his authority as territorial physician, and his explicit threat to involve federal marshals if the family harmed the twins, forced the Donnies to acknowledge that their isolated practices could no longer be sustained in an increasingly connected American society, where unusual infant mortality rates and suspicious family dynamics would inevitably attract official AE.

tension that could no longer be avoided through geographic isolation alone. The twins survived only three days despite Brennan’s best efforts to provide supportive care with the primitive medical equipment available in the remote mountain cabin. Their shared cardiovascular system proved unable to sustain life, and they died quietly during the pre-dawn hours of Brennan’s third day at the homestead.

But their brief existence served as the final undeniable proof of the devastating consequences of the Donnelly family’s genetic manipulation. Consequences that could no longer be hidden from the outside world or rationalized through religious justifications that had become increasingly hollow with each generation of systematic inbreeding.

The twin’s death provided Brennan with the legal authority he needed to conduct a thorough investigation of the family’s practices and medical history. His examination of the 11 small graves behind the cabin, combined with detailed study of the family’s medical journals and genealogical records, revealed evidence of systematic infanticide spanning multiple generations and involving at least 23 documented cases of children who had been eliminated for various genetic defects, ranging from visible physical deformities to behavioral to rates that the family

found unacceptable. Faced with overwhelming evidence and the threat of murder charges that could result in execution under territorial law, Patrick Donnelly finally revealed the full extent of their family history and the systematic genetic experimentation that had consumed five generations of his lineage.

The practice had begun in Ireland during the early 1800s when his great-grandfather Fergus had become obsessed with creating what he called a perfect Irish bloodline through selective breeding techniques adapted from agricultural animal husbandry. The family had justified their actions through a combination of pseudocientific theories about human improvement, twisted religious interpretations that portrayed genetic defects as divine punishment for racial impurity, and social Darwinist philosophies that were gaining popularity among certain educated classes during the mid-9th

century. They had convinced themselves that eliminating defective offspring was not murder, but rather a form of genetic stewardship that would eventually produce human beings superior to the degraded masses of common people.

The psychological toll of maintaining these beliefs and practices across multiple generations had been catastrophic for every member of the family. Patrick himself suffered from chronic anxiety and depression that had worsened dramatically as the genetic consequences of inbreeding became impossible to ignore. Bridg had experienced multiple nervous breakdowns and showed signs of what Brennan recognized as severe post-traumatic stress resulting from years of participating in the systematic murder of her own children. The surviving children presented a tragic spectrum of psychological and physical

damage resulting from both genetic factors and the traumatic environment in which they had been raised. Sheamus, the eldest son, suffered a complete mental breakdown when questioned about his role in the family’s practices, revealing that he had been forced to participate in the elimination of defective siblings from the age of 12.

His profound stutter and inability to maintain eye contact were symptoms of psychological trauma, so severe that Brennan doubted he would ever recover sufficiently to function in normal society. Moira and Colleen, both products of the family’s systematic inbreeding, showed physical and psychological symptoms that would require years of treatment to address.

Both young women had been psychologically conditioned to accept their roles as breeding stock for continuing the family line, and both showed signs of sexual abuse that suggested their father had been preparing them for marriages to their own brothers, the logical continuation of the family’s genetic concentration program.

Young Declan, whose physical deformities made him a living reminder of the family’s genetic failures, presented the most complex challenge for territorial authorities. His spinal curvature and facial asymmetry were progressive conditions that would require ongoing medical treatment, but his psychological state had been so severely damaged by witnessing years of infanticide and abuse that he posed potential dangers to himself and others.

The boy disappeared one night from territorial custody, vanishing into the Montana wilderness without leaving any trace that would allow authorities to determine his fate. The legal proceedings against Patrick and Bridg Donnelly were complicated by the unprecedented nature of their crimes and the territorial justice systems lack of experience with cases involving systematic genetic experimentation and generational patterns of infanticide.

The territorial prosecutor struggled to find appropriate charges for crimes that spanned multiple generations and jurisdictions, while defense attorneys attempted to argue that the defendants were victims of hereditary mental illness rather than calculating criminals who had systematically murdered their own children.

The case attracted attention from medical and legal experts throughout the American territories. But the remote location and primitive communication systems of the era meant that much of the evidence and testimony never reached the broader public.

Patrick and Bridg Donnelly both died in territorial custody before their cases could come to trial. Patrick from what appeared to be a stroke brought on by the psychological stress of having his life’s work exposed as a catastrophic failure and Bridg from complications related to her final pregnancy which ended in yet another severely malformed still birth that seemed to symbolize the ultimate futility of the family’s genetic experimentation.

Dr. Brennan’s detailed documentation of the case became part of early medical literature on the dangers of consanguinius marriage and the genetic consequences of systematic inbreeding. His professional reports published in territorial medical journals and later in national medical publications provided some of the first systematic evidence of the relationship between close family intermarriage and increased rates of genetic abnormalities in offspring. However, he never published the full details of what he had discovered, including the systematic

infanticide and psychological abuse that had characterized the Donnelly family’s practices. Brennan’s private journals, discovered after his death in 1923, revealed his lifelong struggle to understand how human beings could systematically eliminate their own children in pursuit of genetic perfection that existed only in their own twisted imagination.

His notes described recurring nightmares about the conjoined twins and persistent guilt about his inability to save the children who had been murdered before his intervention could protect them. The Donnelly homestead was abandoned after the family’s arrest and the mountain property reverted to territorial ownership when no surviving relatives could be located to claim inheritance rights.

Local residents avoided the area partly due to practical concerns about the harsh winter conditions that had made the location appealing to the family, but also because of growing awareness of the horrors that had taken place there. The isolation that had once protected the family’s secrets now served as a natural barrier that prevented curious visitors from disturbing what had become an unofficial monument to the dangers of genetic experimentation conducted without ethical oversight or scientific understanding. The small cemetery behind the cabin with its 11 documented graves

and evidence of additional unmarked burial sites served as a permanent reminder of the ultimate failure of humanity’s first systematic experiment in genetic eugenics. The neat rows of crosses marking the graves of murdered infants stood as testimony to the moral bankruptcy of theories that valued genetic purity over basic human decency and parental love.

In the decades following the exposure of the Donnelly family’s practices, similar cases began to emerge in other isolated American communities, suggesting that the Montana family had not been unique in their experimentation with human breeding techniques.

The growing body of evidence about the genetic and psychological consequences of systematic inbreeding contributed to changing attitudes about marriage laws, child protection, and the need for government oversight of isolated communities. that might be conducting practices harmful to their members or to society as a whole.

The legacy of the Donnelly family’s genetic experiment extended far beyond their own tragic story. Their case provided early evidence for genetic theories that would later become fundamental to modern understanding of heredity. While their systematic infanticide practices contributed to evolving legal and ethical standards for child protection that would eventually make such family-based eugenics programs impossible to sustain in American society.

This mystery shows us how the pursuit of genetic perfection can lead to unthinkable horrors when combined with isolation, desperation, and a fundamental misunderstanding of human worth and scientific principle. The Donnelly family’s centurylong experiment in selective breeding represents one of the darkest chapters in the intersection of family secrets, primitive genetic science, and the American frontiers tolerance for communities that operated beyond the boundaries of civilized moral standards. Their story serves as a permanent warning about the dangers of treating human beings as experimental

subjects in pursuit of theoretical improvements that exist only in the minds of those who have lost all sense of basic human decency and parental love. What do you think of this story? Do you believe everything was revealed about the Donnelly family’s practices? Or might there be other isolated families who carried similar dark traditions to the American frontier?

News

A husband, after 17 years of marriage with Inna, decided to leave her for a young student, but he didn’t expect his wife to give him a farewell he would never forget.CH2

A husband, after 17 years of marriage with Inna, decided to leave her for a young student, but he didn’t…

My Brother Clapped as Mom Slapped Me In Front Of 55 People. Dad Sat Back, Beamed, and Said, “Serves You Right.” But What They Didn’t Know? That Night, I Made Three Calls… and Watched Their Dreams Shatter.CH2

My Brother Clapped as Mom Slapped Me In Front Of 55 People. Dad Sat Back, Beamed, and Said, “Serves You…

I was folding laundry in the hallway when I froze. From my 5-year-old daughter’s room came the softest whisper, her little voice carrying words that made my stomach drop.CH2

I was folding laundry in the hallway when I froze. From my 5-year-old daughter’s room came the softest whisper, her…

“We couldn’t not come to your anniversary!”” — The cheeky in-laws showed up at the restaurant uninvited.CH2

“We couldn’t not come to your anniversary!”” — The cheeky in-laws showed up at the restaurant uninvited Lera had always…

I Filed for Divorce After Catching My Husband Cheating — But in Court, Our 7-Year-Old Son Stood Up… And What He Said Changed Everything.CH2

I Filed for Divorce After Catching My Husband Cheating — But in Court, Our 7-Year-Old Son Stood Up… And What…

College Friends Vanished on a Mountain Trip — 2 Years Later, Hikers Found This in an Abandoned House…CH2

College Friends Vanished on a Mountain Trip — 2 Years Later, Hikers Found This in an Abandoned House… In…

End of content

No more pages to load