She Was Abandoned After Having 8 Children — Until He Treated Her Like a Queen

I can’t do this anymore, Ruth. I never signed up for this many mouths. That was the last thing James said before he slammed the door of their cabin, his boots kicking up dust as he disappeared down the dry trail without once looking back. He didn’t even take a horse. Just left. Left her with six children, a cow that had stopped giving milk, and a sack of flour that was already more weevil than wheat.

Ruth stood in the doorway, the baby on her hip, and her four-year-old tugging at her skirts. Her oldest, Jeremiah, barely 11, stared after his father with a tight jaw, not crying, just standing there with his fists baldled. The others were quiet, too. It wasn’t the first time James had left. But it was the first time he did it after saying those words.

She never signed up for this either, but here she was. The cabin was too small for quiet. Every board creaked. Every sigh echoed. That night, after putting the kids to bed on their straw mats, she sat by the cold stove and listened to the wind beat against the walls like it was trying to get in and finish what James had started.

Her hands trembled as she picked up her sewing, trying to mend one of Joseph’s shirts for the third time. Her eyes burned, but the tears didn’t fall. They never did anymore. The days that followed blurred into each other like the dust on the horizon that never settled. Ruth woke before the sun, drew water from the well, made cornmeal cakes, and prayed the eggs wouldn’t run out before she could figure out something else.

She walked the mile to town with the baby in a sling, and the rest trailing behind, trying to trade sewn cloths or patched up shirts for sugar or coffee beans. Mostly, she came home with nothing. Some folks looked at her with pity. Some didn’t look at all. And a few said things that weren’t meant to be heard by children, but were six kids and no husband.

That James knew what he was doing running off like that. She always looked a little proud for someone in her position. Ruth didn’t talk back. She just pulled her shawl tighter, kept her head down, and moved along. Not because she was ashamed, but because she didn’t have the time to waste proving herself to people who had already made up their minds.

Continue below

What she did have time for was work. There was always work. Fixing the fence that kept leaning like it wanted to lie down and never get up again. Teaching her kids how to read using old newspapers and her own Bible. Selling pies when she could scrape together apples and lard. Sometimes she’d find someone in town willing to pay her a few cents to clean or cook.

She took every offer, no matter how small. Because small coins kept oil in the lamp and flour in the sack. By spring, her hands had toughened like rawhide. Her back achd before noon, and her dresses hung looser than they had when James left. But the kids were growing, and they were still with her. That counted for something.

It was late May when she first saw him. She was in town with Jeremiah, who was carrying a basket of mended shirts they hoped to sell at the dry goods store. Ruth had her hair pinned up, her apron stained from the morning’s breadmaking, and the baby was sleeping against her chest.

They passed the saloon, and a man stepped out, tall and quiet, with a battered hat and a beard that hadn’t seen scissors in a while. His shirt was clean, though faded, tucked into worn jeans, and a gun hung at his side, not for show. He didn’t lear at her like some men did. He just watched her for a second, then tipped his hat.

She nodded back, barely. Jeremiah glanced at her as they walked on. “You know him?” “No,” she said. “Just being polite. Later she asked Mr. Turner at the store who the man was. He said, “That’s Marshall Walker. Came up from Leach a few months back. Quiet type. Lost his wife in a fire last year. Folks say he keeps to himself.

” She forgot about him until a week later when the cow got sick. She was out in the field with Jeremiah trying to coax the animal to drink water when hooves sounded on the road. Ruth turned, her hand already on Jeremiah’s shoulder to pull him back, but it was Marshall Walker. He reigned in his horse by the fence and looked down at the cow.

She eaten? Ruth shook her head. Not since yesterday. He nodded once, then dismounted without asking. He came over, knelt by the cow, checked her gums, and frowned. Might be bloat. I can bring some oil tomorrow. Help it pass. Ruth hesitated. Why would you help? He stood. Because she needs it, and you look like you got enough to carry.

He left without waiting for thanks. The next day, he returned. True to his word, he brought linseed oil, helped her feed it to the cow, and stayed until the animal was standing again. He didn’t ask for anything in return. That summer he came by twice more. Once to help fix the corner post that had snapped in a storm.

And another time when he brought extra seed potatoes, saying he had more than he needed. He never stayed long, never spoke more than a few sentences. But he always looked her in the eye like she was worth speaking to, like she wasn’t just a worn out woman raising too many kids alone. Ruth wasn’t used to kindness that didn’t have a price. In August, the twins got sick.

Fever, coughing, too weak to stand. Ruth did all she could. Boiled water, mashed onions for puses, prayed harder than she had since she was a girl. Then one evening as she sat on the porch with one of the boys burning up in her lap, a writer came up. It was Walker. Doc Simmons is in town, he said. I told him you needed him.

She didn’t have words, just nodded, her throat tight. The doctor came later that night, brought medicine. The twins pulled through. After that, things changed. She started noticing how Walker always stood with his back to the wind, shielding her from dust when they spoke. How he looked at her kids with a kind of quiet understanding, like he saw them as people, not burdens.

How he spoke to Jeremiah like a man, not just a boy. One afternoon, Ruth baked an extra pie and brought it to the marshall’s office. She left it on the table without saying much. He looked at it then at her and said, “Thank you, ma’am. That means a lot.” That was it. No flowery words. No expectations. Just a simple moment between two people who understood what it meant to go without and to be seen.

By September, Ruth had work at the schoolhouse, helping clean and cook lunches. It didn’t pay much, but it was steady. Jeremiah helped Mr. Turner at the store in the mornings. The girls were learning to sew. The family was still poor, but no longer desperate. And Walker, he kept coming around. Not often.

Just enough that the kids started asking when he’d come back. Ruth didn’t know what to call it. She wasn’t ready to believe in hope again. Not after all that had happened. But sometimes when she caught Walker watching her from across the town square, she let herself think. Maybe, just maybe, not everyone left. One evening, as she swept the porch and the sun dipped low behind the hills, she heard footsteps.

Not heavy like James’ had been. Calmer. She turned and saw Walker at the fence. “Ruth,” he said, nodding. She straightened. Marshall. He held out a jar. Picked peaches. Thought the little ones might like some. She took it carefully. They’ll love it. Thank you. He lingered. Then said, “You ever need anything? You just send word.

Not because I think you can’t handle it. I know you can. Just don’t want you thinking you have to do it all alone.” She stared at him for a long moment. And then for the first time in years, Ruth smiled. Not the kind she wore like armor. A real one. That’s kind of you, Marshall. He tipped his hat and turned to go.

But before he did, he paused. Name’s Thomas, he said. Then he walked away, leaving behind the scent of peaches and something else Ruth hadn’t felt in years. possibility. Fall came quick to Dry River. The wind picked up first, carrying dust and brittle leaves. Then the nights grew colder, creeping into their bones, no matter how close they huddled near the fire.

Ruth patched up every crack in the cabin walls with cloth scraps and clay, though it didn’t do much. Still, it was better than the winters she remembered from the northern towns she’d once passed through. At least here, the cold didn’t come with snow. The schoolhouse job continued through October, though the pay never increased. But Ruth was thankful for the structure.

It gave her something solid to work around, and it meant the younger ones got a warm meal once a day. Most of the kids didn’t know they were poor. They played with stones, sticks, and imagination. Ruth did her best to make sure it stayed that way. Jeremiah kept growing faster than she could keep up with. He was already borrowing one of Thomas’s old jackets, which the marshall had dropped off without comment.

It hung big on the boy, but he wore it proudly. Ruth had noticed how Thomas never made a show of his help. If he gave something, it was left on the fence or handed over with a quiet comment and a respectful nod. No expectation, no judgment. That made it easier for her to accept, even if part of her still wrestled with the pride she’d built up to survive.

One Saturday afternoon, Thomas arrived unannounced. Ruth had just wrangled the kids down for chores, the baby perched in a basket while she kneaded dough at the kitchen table. She heard the horse first, then the knock. When she opened the door, Thomas stood there with a folded paper in hand. There’s a job fair up in Clifton next week.

Couple of folks from the rail line are passing through. They’re looking for cooks and cleaning help for the new line camps. Thought maybe you’d want to know. Ruth looked down at her flowercovered hands. Would it be steady? He nodded. Sounds like it. Not glamorous, but decent pay. You wouldn’t have to leave town, just work a few days a week when the crews rotate in.

Her stomach twisted at the thought of more time away from the kids. But then she thought of the nearly empty flower sack. Thank you for telling me. I can take you up there, he added. If you decide to go. Ruth paused. That’s kind of you. I’ll think on it. She closed the door gently after he left, the paper in her hand, her mind already spinning.

That night, she told Jeremiah about it. He was quiet a moment, then said, “We’ll manage, ma, if it means we can fix the roof and maybe buy real shoes for the girls.” His words settled like a stone in her chest. He wasn’t a boy anymore. He hadn’t been for a while. She didn’t want to need her son to grow up that fast.

But life didn’t wait for her comfort. The next morning, she gave Thomas her answer. He arrived with his wagon and two horses, having somehow learned she didn’t trust herself to ride anymore. She brought the baby and left the rest with Jeremiah. As they rode toward Clifton, Ruth found herself glancing at Thomas more than once.

He didn’t talk much, just pointed out the turnings, the ranches they passed, or offered water when she coughed. When they arrived, the small town bustled with railmen and vendors. Ruth clutched her shawl tighter as she stepped down, nerves bunching up in her stomach. “I’ll wait by the horses,” Thomas said. She nodded and walked toward the building where the job fair was being held.

Inside the air smelled of tobacco and pine cleaner. She filled out her name on a list, answered questions from a tired looking man in suspenders, and waited. When her turn came, she explained her experience, her cooking, and the way she managed six children on pennies. The man scratched something on a form and gave a brief nod. We could use someone like you.

First rotation starts next month, two days a week. Pays decent cash. She nodded. I’ll take it. Walking out into the cool air, her steps were lighter, though her heart raced from the unfamiliar feeling of something going right. Thomas tipped his hat. Good news. She allowed herself the briefest smile. Good enough.

They rode back mostly in silence, but it wasn’t uncomfortable. The land stretched wide around them, and she watched the hills glow in the afternoon light. She found herself thinking that silence with Thomas was different. It didn’t make her feel invisible. That evening, when she stepped off the wagon, Jeremiah ran out to greet her.

“Did it go well?” “We’ll have meat next month,” she said, ruffling his hair. Thomas lifted the baby gently from the wagon seat and handed her to Ruth without a word. She watched the way he did it carefully, respectfully, like the child was precious and not just another burden. Ruth looked at him, trying to find the right words, but all she managed was, “Thank you, Thomas.

” He looked down at the baby, then back at Ruth. Anytime. And then he was gone, dust rising behind his horse as the sun dipped lower behind the mountains. The weeks that followed passed with a steadier rhythm. Ruth began her rotation with the rail camp, and Thomas helped with the wagon whenever she needed it. He never lingered, never asked questions, but he always showed up.

And for the first time in a long while, Ruth didn’t feel like she was fending off the world alone. One evening, as the wind howled outside, and the kids played quietly by the fire, Ruth sat with a cup of tea and stared at the door. She wasn’t waiting, not exactly, but part of her couldn’t stop wondering when she might hear those calm, even footsteps again.

The first snow fell in early December, light and quiet, covering the hills like a second skin. It melted by morning, but it was a sign. Winter was coming for real, and Ruth had been preparing in every way she could. The children had coats now, secondhand and patched, but warm.

The pantry held jars of preserved vegetables and canned peaches, thanks in part to Thomas bringing over fruit during harvest. She had taken the rail camp job for 2 months now, and the pay had helped patch the roof, buy new boots for Jeremiah, and even surprised the twins with molasses candy once. Still, every day felt like she was balancing on a beam stretched over an open canyon.

One unexpected twist could send it all tumbling. The day before Christmas, Ruth stood in front of her stove, making biscuits from what remained of the flower. The fire was strong, and the smell filled the small cabin. The children had made paper garlands to hang above the hearth, and someone had found pine branches to lay across the table.

It wasn’t much, but it felt like something close to joy. That afternoon, a knock sounded on the door. Ruth wiped her hands and opened it to find Thomas holding a wooden crate. His hat was dusted with snow, and his cheeks were red from the cold. “Merry Christmas,” he said, setting the box down just inside the door.

Inside were oranges wrapped in paper. real oranges, a tin of coffee, a sack of flour, and six handmade wooden toys, one for each child. Ruth stared at the box for a moment, then looked up at him. Thomas, this is too much. He shook his head gently. Not enough. I figured maybe they could use something to smile about. behind her.

The children had already crowded near, gasping at the toys. The baby clapped her hands. Ruth stepped outside and closed the door behind her. The cold bit at her hands, but she needed the space. I never asked for charity, she said. Thomas met her eyes. I know this isn’t charity. It’s what people do when they care. She said nothing.

You’ve worked harder than anyone I know. He continued, “You didn’t give up. You didn’t leave. You made a life for them, Ruth. You built something out of nothing. And if I can help keep that going, I will.” His voice was calm without pressure. And there was no flattery in it. Just plain truth.

She looked down at her boots, the snow melting around the toes. “What do you want in return?” she asked, barely above a whisper. He was quiet for a long time. Then he said, “Time, respect, and maybe, if it ever feels right to you, a place at your table. Not tonight, not tomorrow, just someday.” Ruth didn’t answer, but she didn’t walk away either.

That night, the children laughed around the fire, playing with their new toys, cheeks red from excitement. Ruth sat near the window, watching the snow come down soft and steady. She thought about everything Thomas had said, about everything he hadn’t said, about how for once someone saw her not as a burden or a failure, but as a person worthy of help and love without condition.

The weeks that followed passed like snow drifts, slow and quiet, then suddenly changing. Thomas came by once a week, sometimes with feed for the animals, sometimes with a book for the children. He never stayed too long, but his presence became part of their routine. Jeremiah took to him easily, asking questions about horses, about law work, even about cooking.

One early spring morning, Ruth woke to the sound of the front gate creaking. She stepped outside to see Thomas already there hammering a new latch onto the fence post. It kept swinging open, he said simply. She watched him work for a moment, the steady movements of a man who never rushed. Then she said, “Would you like to stay for supper tonight?” He paused, straightened, then nodded once. “I would.

” That night, Ruth set out what she could. Roasted vegetables, cornmeal biscuits, and the last of the preserved peaches. The children behaved like they’d been waiting for this moment. Thomas sat at the table like he’d always belonged there. He listened to each child with genuine interest, even helped the twins untangle their wooden puzzles.

After supper, Ruth walked him out. The stars stretched above the fields and the breeze had lost its bite. “You didn’t have to fix the gate,” she said. “I know,” he replied. “But I wanted to.” They stood in silence for a long moment. “I was angry for a long time,” Ruth admitted. Not just at James, at myself. For letting it happen, for believing him, for not seeing how close I was to breaking.

Thomas looked at her, his expression soft but steady. There’s strength in survival, Ruth. That anger, it kept you going. Nothing wrong with that. But maybe now you don’t have to carry it alone. She nodded slowly. I don’t know how to let it go. One day at a time with someone beside you maybe. She looked up at him. And you think that someone could be you? He smiled just a little.

I hope so, but only if you want that, too. Ruth didn’t answer right away, but she reached out and touched his arm. A brief, gentle gesture, and he didn’t move. Didn’t flinch. just stood there with her in the quiet spring night. By summer, it was no longer strange to see Thomas sitting on the porch steps, whittling a piece of wood while the children played.

It wasn’t unusual for him to carry the baby or help Ruth carry water from the well. Neighbors who once whispered about her now nodded as they passed. No one said much, but something had shifted. On the first Sunday of June, Thomas asked her to walk with him to the small church on the hill. Ruth hesitated at the door, smoothing her dress with trembling hands.

“I haven’t been in years,” she said. “Doesn’t matter,” he replied. “You’re welcome there and here.” They walked together slowly, hand in hand. No one stared when they entered. The children sat quietly in the front pew. Ruth held her head high. After the service, the preacher came up and shook Thomas’s hand. Then he turned to Ruth.

Good to see you here, Mrs. Lyall. She didn’t correct him. Not yet. But a few months later, she would because by then she would have a new name and a new ring and a home where the door never slammed shut in anger. Where no one walked away because life got hard. A home where someone looked at her and saw a woman who had given everything and still had more to give.

She had been abandoned. She had been judged. She had been pushed to the edge, but she hadn’t fallen. And in the end, she hadn’t been alone. She had six children and someone who treated her like a queen.

News

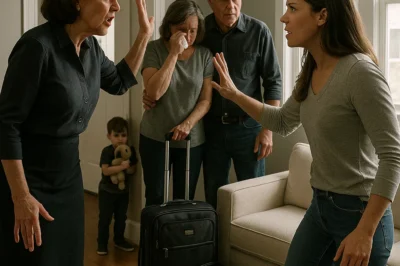

My mother-in-law kicked my parents out of my apartment while I wasn’t home—but in the end, she only made things worse for herself.CH2

My mother-in-law kicked my parents out of my apartment while I wasn’t home—but in the end, she only made things…

At the wedding, something started moving under the bride’s dress! The groom turned pale…CH2

At the wedding, something started moving under the bride’s dress! The groom turned pale… The garden sparkled in the sunshine…

Millionaire kicks a poor beggar in the market not knowing that she is the lost mother he has been searching for years…CH2

Millionaire kicks a poor beggar in the market not knowing that she is the lost mother he has been searching…

The little girl cried and told her mother, “He promised he wouldn’t hurt.” The mother took her to the hospital, then the police dog discovered the shocking truth…CH2

The little girl cried and told her mother, “He promised he wouldn’t hurt.” The mother took her to the hospital,…

“She wasn’t the one keeping the real secret” – Phillies’ Karen scandal takes a darker turn as online investigators claim the truth may hinge not on her outburst, but on the silent man at her side whose identity could blow the case wide open

“She wasn’t the one keeping the real secret” – Phillies’ Karen scandal takes a darker turn as online investigators claim…

“She swore she would never forgive this country” – Phillies’ Karen stuns the world by vowing to leave America for good, but it was 8 POWERFUL words from Karoline Leavitt that shattered the moment and left the entire room in stunned disbelief

“She swore she would never forgive this country” – Phillies’ Karen stuns the world by vowing to leave America for…

End of content

No more pages to load