How did my sister’s wedding turn into a crime scene in under 20 minutes?

How did my sister’s wedding turn into a crime scene in under twenty minutes? The question echoed in my head like a pulse that wouldn’t stop beating. Even now, replaying the details feels surreal, like watching a film I never agreed to star in. It began innocently enough—an early autumn afternoon in a restored countryside estate two hours outside Milwaukee, where the air smelled faintly of wildflowers and damp grass. Rows of white chairs lined a cobblestone path that led to a floral archway so elaborate it looked like it belonged in a royal wedding magazine spread. My sister, Felicity, had always been dramatic that way—every moment needed to look perfect, every photo needed to shimmer with curated happiness.

I sat in the second row, surrounded by relatives who smelled like perfume, nerves, and champagne. The glass in my hand sparkled golden under the soft sunlight filtering through the canopy of trees above. I remember thinking how beautiful the day was, how strange it felt to see Felicity walking down the aisle in that lace-covered gown that clung to her figure like fog over water. Everything seemed so still, so poised, until I took that one sip. Just one. That was all it took for the perfect day to fracture.

The taste hit me instantly—wrong, bitter, like sucking on pennies and chalk. It wasn’t the crisp sweetness of champagne I knew. My tongue felt coated in something metallic, thick and unpleasant. I swallowed anyway, too polite, too unsure to make a scene. But within seconds, my throat tightened. My pulse quickened in my ears. I set the glass down carefully, afraid it might slip from my trembling hand. Around me, people smiled, whispered, adjusted their phones to take pictures. The string quartet began Canon in D, and though I knew the melody by heart, it sounded warped and distant, as if the notes were trapped underwater.

A wave of dizziness washed over me so strong I had to grip the edge of the chair to keep from falling. My fingers tingled first, then my legs, and a cold realization began to spread through me: something was seriously wrong. I blinked rapidly, trying to clear the fog creeping into my vision. The bright colors of the flowers began to blur together. My breath came faster. I tried to stand, to signal someone, but my knees buckled as if my body no longer belonged to me. I collapsed halfway into the aisle, my heart slamming against my ribs.

Before I could call for help, a hand clamped onto my arm—sharp, strong, controlling. Diane. My sister’s new mother-in-law. She was sixty, perfectly coiffed, and always carried herself with the kind of authority that dared anyone to question her. Her grip hurt. She yanked me upright with surprising force and hissed under her breath, “You are making a scene. Sit down. Now.”

Her voice was quiet enough not to interrupt the ceremony, but the venom in her tone was unmistakable. Her breath smelled faintly of mint and expensive cabernet. She pushed me back into my chair, her nails digging into my skin. My heart was pounding, the edges of the world spinning into soft shadows. I tried to tell her—something’s wrong, my drink—but my mouth wouldn’t form the words. My tongue felt thick, heavy, useless. The sound that came out of me was a slurred, broken mumble.

She leaned closer, so close I could see the faint shimmer of foundation over her wrinkles. “I know what you’ve done,” she whispered, her voice cold enough to freeze the air between us. “You’ve been trying to steal attention from Felicity all week. You couldn’t stand that it wasn’t about you for once, could you? Just like your mother.”

Her words stung in a way I couldn’t even process. I could barely breathe. My skin was clammy. My vision tunneled so much that the altar became just a blur of white and gold. The officiant’s voice droned faintly in the distance—something about love and forever—while my body screamed in silent panic. I tried to raise my hand, tried to say I needed help, but Diane’s fingers suddenly pressed over my mouth.

Her hand smelled faintly of perfume and soap, but all I could taste was iron as my teeth cut into my lip. She pressed harder, silencing me completely while everyone else watched the bride and groom. I could see Felicity’s back, her veil trembling slightly in the breeze, her posture flawless, serene. She looked over her shoulder once—just once—and caught sight of me slumped in my chair. Instead of concern, her eyes flashed irritation. She thought I was ruining her moment. That look broke something in me even as my mind struggled to stay clear.

The officiant reached the familiar line—“If anyone objects…”—and I wanted to scream, to shout that someone had poisoned me, that something was terribly wrong. But Diane’s hand stayed where it was, pressing down like a weight. The world around me dulled, the laughter, the soft sniffles of relatives, the rustle of dresses—it all faded until it felt like I was slipping underwater. My pulse throbbed painfully in my neck.

When Diane finally pulled away, the ceremony was over. The crowd erupted into applause as Felicity and her husband kissed. My body gave out completely. I fell forward into the back of the guest seated in front of me. They turned around, irritated at first, then startled. “Are you okay?” they asked. I could see their lips move, but it was like I was hearing them from the other end of a tunnel. I couldn’t answer. My body slid from the chair onto the grass, my fingers twitching weakly.

Gasps rippled through the crowd. A few guests stood up, craning their necks to see what had happened. The world tilted sideways. I could hear someone say my name, another voice calling for water, for help, for something. My chest felt tight, as if an invisible hand was squeezing it. Each breath became harder than the last. Terror bloomed inside me—I knew what was happening. This wasn’t alcohol or anxiety. This was poison.

I tried to whisper it. I tried to form the words. But all that came out was a distorted sound. My throat felt raw. Diane pushed through the circle that had formed around me, her face composed, her tone sharp and rehearsed. “She’s fine,” she said loudly, forcing a brittle laugh. “She’s had too much to drink, that’s all. She always does this when she’s upset.”

People hesitated. Some looked skeptical, but no one wanted to challenge the authoritative mother-in-law of the groom. Diane smiled tightly, insisting, “Let’s not make a scene. I’ll take care of her.”

Two groomsmen—broad-shouldered, polite, and clueless—followed her orders. They lifted me under the arms, their laughter uncomfortable as my body sagged between them. I tried to beg them not to, to say I needed a doctor, a hospital, but my mouth wouldn’t obey. My voice came out in garbled nonsense that made one of them chuckle awkwardly.

They carried me past the guests and up the side path toward the mansion that overlooked the garden. The world blurred past in patches of color—green hedges, white roses, the flicker of camera flashes. I wanted to scream that Diane was lying, that she was hiding something, but all I could do was gasp weakly as they hauled me inside.

The interior of the mansion was cool and dim, the air smelling faintly of furniture polish and old books. They brought me down a narrow hallway to a small room at the back—a storage space lined with shelves of dusty linens and unused decorations. The couch they dropped me onto sagged beneath me, its fabric rough and faded. Diane followed behind them, her heels clicking sharply against the wooden floor.

“Just leave her here,” she instructed briskly. “She needs to sleep it off.”

The men hesitated for a second, uncertain. “You sure she’s okay?” one asked.

“She’ll be fine,” Diane said, her voice so certain that it left no room for argument. “Close the door behind you.”

They obeyed. I heard the door shut, then the distinct metallic sound of a lock clicking into place. I was trapped. My heart pounded in terror. The air in the room felt heavy and stale. I tried to lift my head, to crawl, to move—but my limbs wouldn’t respond. The couch’s fabric felt rough against my skin, and every breath hurt more than the last.

My phone was in my purse, still sitting on the chair outside where I’d left it. There was no window, no way out, no light except a faint yellow bulb that flickered occasionally. I could hear the muffled sounds of laughter and music from the reception outside, so painfully distant from where I was lying on that old couch.

Time blurred. I drifted in and out of consciousness, unsure if minutes or hours had passed. My body felt numb, my mind foggy. Somewhere through the haze, I heard voices. They were just beyond the door, low and urgent. Diane’s voice was unmistakable, cold and controlled as ever.

“She’ll be fine,” she was saying. “You know how she is. Always jealous, always looking for attention. I warned Felicity this would happen.”

A man’s voice responded, uneasy. “Still, maybe someone should check on her. She didn’t look right.”

“Let her sleep,” Diane snapped. “We’ll deal with her after the reception.”

Footsteps retreated. Silence followed. I tried to scream, to make noise, to let them know I wasn’t sleeping—I was dying—but the sound stuck in my throat. My eyes rolled back. My vision flickered. I was alone, locked in that suffocating room, the sound of distant laughter floating in through the walls while my world slipped further away.

And that was the moment I realized the nightmare had only just begun.

Continue below

How did my sister’s wedding turn into a crime scene in under 20 minutes? My sister Felicity was halfway down the aisle when I realized the champagne I just sipped tasted wrong, bitter and chalky with this weird metallic aftertaste that made my tongue feel thick. I set the glass down on my lap and tried to focus on the ceremony, but my vision started getting blurry around the edges.

The string quartet playing Canon and D sounded like it was underwater and far away, even though they were only 20 ft from where I sat in the second row. My hands started tingling first, then my feet, and I looked down at the champagne flute, realizing something was seriously wrong with whatever I’d just drunk. I tried to stand up to get help, but my legs wouldn’t cooperate, and I ended up half falling into the aisle.

Felicity’s new mother-in-law, Diane, rushed over and grabbed my arm hard enough to bruise, yanking me back into my seat with surprising strength for someone in her 60s. She hissed in my ear that I was making a scene at my sister’s wedding and needed to sit down and be quiet like a proper bridesmaid. Her breath smelled like expensive wine and mint gum, and her fingers dug into my bicep as she forced me to stay seated while my heart started racing in my chest.

I tried to tell her something was wrong with my drink, but my words came out slurred and wrong, like my mouth wasn’t working right anymore. Diane leaned in closer and whispered that she knew exactly what I’d done, that she’d watched me trying to steal attention from Felicity all week with my complaints and drama. She said I was just like my mother, always causing problems and ruining special moments for everyone else.

My vision tunnled even more, and I could feel my pulse hammering in my neck and temples while sweat started soaking through my bridesmaid dress. The officient was asking if anyone objected to the marriage, and I wanted to scream that someone had poisoned me. But Diane’s hand clamped over my mouth before I could make a sound.

She pressed so hard I tasted blood from where my teeth cut into my lip, and her other hand stayed locked around my arm, keeping me pinned to that chair. I tried to bite her hand or scratch her or do anything to get free, but my body felt like it was moving through syrup, and nothing worked the way it should.

My head lulled to the side, and I saw Felicity looking back at me with this annoyed expression like I was deliberately trying to ruin her perfect day. The ceremony kept going while I felt myself slipping further away from consciousness. I could hear the vows being exchanged, but they sounded muffled and distant, like I was listening from the bottom of a swimming pool.

Diane finally let go of me once the kiss happened, and everyone started clapping, and I immediately slumped forward onto the person in front of me. They turned around, looking irritated until they saw my face, and their expression changed to concern. They asked if I was okay and tried to help me sit up, but I couldn’t hold my own weight anymore and ended up sliding off the chair onto the ground between the rows of white folding chairs.

People started noticing then, and a few guests gathered around asking what was wrong while I lay there, unable to move or speak properly. My chest felt tight and breathing was getting harder with each attempt and I realized with absolute terror that this wasn’t just being drunk or having a panic attack.

Someone had actually poisoned that champagne and I was dying right there on the ground at my sister’s outdoor wedding while everyone stood around confused about what to do. Diane pushed through the small crowd that had formed and announced loudly that I was clearly drunk and had embarrassed myself and the family.

She told everyone to give me space and let me sleep it off in one of the back rooms at the venue. Two groomsmen I didn’t know picked me up under Diane’s direction and started carrying me away from the ceremony area toward the old mansion that served as the venue’s main building. I tried to tell them I needed a hospital, that someone poisoned me, but all that came out was garbled nonsense that made them laugh like I was just really wasted.

They hauled me up the back of the mansion and into a small storage room that smelled like dust and old furniture, then dumped me on a motheaten couch before leaving and closing the door behind them. I heard the lock click and realized Diane had just had me imprisoned in this room while whatever was in that champagne worked its way through my system.

My phone was back at my seat in my purse and there was no way to call for help and the room had no windows, just shelves of old decorations and boxes of linen stacked against the walls. I don’t know how long I lay there drifting in and out of consciousness. But at some point, I heard voices outside the door.

Diane was talking to someone in hushed urgent tones about how I’d always been jealous of Felicity and had probably taken something to get attention. The other voice, a man’s, said they should probably check on me to make sure I was okay, but Diane insisted I just needed to sleep it off and they’d deal with me after the reception.

I tried to scream or make noise to let them know I was actually dying, but my voice wouldn’t work anymore and I could barely keep my eyes open. The footsteps walked away and I was alone again in that dark, musty room with my heart beating irregularly and my breathing getting shallower. I remember thinking about how my mom died when I was 12 from an undiagnosed heart condition and how ironic it would be if I died at age 19 from poisoning at my sister’s wedding.

The edges of my vision went completely black and I felt myself slipping away into unconsciousness, wondering if anyone would even notice I was gone until it was too late to save me. When I woke up, there were paramedics standing over me, shining lights in my eyes and asking me questions I couldn’t answer. One of them was putting an IV in my arm, while another took my blood pressure and looked worried.

I heard one say my heart rate was dangerously low and my blood pressure was crashing, and they needed to get me to the hospital immediately. They loaded me onto a stretcher and carried me down the narrow back stairs. And when we emerged into the main reception area, everything had stopped. The music was off, the guests were all standing in confused clusters, and there were police officers everywhere talking to people and taking statements.

I saw Felicity standing near the head table still in her wedding dress with mascara running down her face and our dad next to her looking older than I’d ever seen him. Diane was in handcuffs being led away by two officers while she screamed about how this was all a misunderstanding and she’d done nothing wrong.

The paramedics rushed me past all of it and loaded me into the ambulance. And the last thing I saw before they closed the doors was my sister’s destroyed reception with overturned chairs and abandoned plates of food and wedding cakes smashed on the ground where someone had knocked over the dessert table. The hospital was a blur of tests and doctors and nurses asking me the same questions over and over.

What did you drink? When did the symptoms start? Did you see who gave you the champagne? I answered as best as I could through the fog in my brain, telling them about the bitter metallic taste and how Diane had forced me to stay quiet and then locked me in that storage room. They took blood samples and hooked me up to monitors that beeped constantly, tracking my heart rate and oxygen levels while pumping fluids and something they called activated charcoal through my IV to absorb whatever toxin was in my system. A doctor with kind eyes and gray hair explained that they’d found high levels of prescription sedatives in my blood mixed with something else they were still trying to identify. She said, “If I’d gone much longer without treatment, I probably would have stopped breathing completely.” The police came to interview me while I was still in the emergency room.

A detective named Foster, who had a gentle voice and took detailed notes while I described everything that happened. He showed me photos on his tablet of the champagne flute I’d been drinking from, now bagged as evidence, and asked if I recognized it or remembered where it came from. I explained that all the champagne flutes looked identical at the wedding, crystal glasses with the couple’s initials etched on the side.

I’d grabbed mine from a tray being passed around by servers before the ceremony started, and I’d only taken maybe three sips before everything went wrong. Detective Foster nodded and wrote something down, then asked about my relationship with Diane, and whether she’d ever threatened me or acted hostile before.

I told him about the comments she’d made all week leading up to the wedding. Little digs about how I was too young to be a bridesmaid, and how I was probably jealous of Felicity’s success. She’d made a big deal about me being in community college while Felicity had her master’s degree and a six-f figureure job, like my life choices were somehow a personal insult to the family.

Detective Foster asked if anyone else had heard these comments, and I gave him names of other family members who’d been present during various conversations. He thanked me and said he’d be in touch once they knew more about what exactly had been in my system, then left me alone with the beeping monitors and the IV drip slowly clearing poison from my blood.

Dad showed up around midnight, still wearing his Father of the Bride tuxedo, but with his bow tie undone and hanging loose around his neck. He looked exhausted and confused and angry all at once, and he pulled a chair up next to my hospital bed without saying anything for a long moment.

Finally, he asked me what happened in this broken voice. I’d never heard him use before. And I told him everything from the beginning. He listened with his head in his hands. And when I finished, he said the police had arrested Diane for assault and attempted poisoning, and that they’d found a bottle of prescription sleeping pills in her purse along with something called GHB.

I asked him why she would do this, and he shook his head, saying he didn’t know, but the police had theories. Apparently, several guests had seen Diane tampering with drinks before the ceremony, and one of the catering staff had reported seeing her pour something from a small vial into one of the champagne flutes. Dad said Diane claimed she’d only meant to make me sleepy so I wouldn’t cause drama during the ceremony, but the combination of drugs she’d used had nearly killed me instead.

He started crying then, really sobbing, and apologized over and over for not protecting me and for not seeing how toxic Diane had become toward me over the past year. Felicity came to visit the next morning, and she looked like she’d aged 5 years overnight. Her hair was still partially styled from the wedding, but her face was bare and puffy from crying, and she wore sweats instead of her honeymoon clothes.

She sat on the edge of my hospital bed and took my hand, and we both just cried together for a while without talking. Eventually, she told me that her new husband, Jeffree, had wanted to cancel the entire reception and come to the hospital with me, but by the time they realized how serious it was, the police had already arrived and started their investigation.

She said watching them take Diane away in handcuffs while I was being loaded into an ambulance was the most surreal experience of her life. Felicity apologized for not believing something was wrong when she saw me slumping over during the ceremony, for assuming I was just being dramatic or seeking attention like Diane had been saying all week.

She admitted that Diane had been planting seeds of doubt about me for months, making little comments about how I was jealous of Felicity’s success and would probably do something to ruin the wedding. Felicity had dismissed it as just future mother-in-law drama. But now she realized Diane had been setting up a narrative to explain away whatever she was planning to do to me.

The toxicology reports came back 3 days later, showing I’d ingested a dangerous combination of Rohypnol, prescription sedatives, and a veterinary tranquilizer that Diane had apparently stolen from her job at an animal clinic. The mixture should have killed me, according to the doctors, and the only reason I survived was because I’d only consumed about a third of the doctorred champagne before my body started reacting.

Detective Foster came back to tell me they’d charged Diane with attempted murder, aggravated assault, false imprisonment, and several other crimes I couldn’t keep track of. He said they’d found evidence on her phone of her researching how to make someone appear drunk or sick, and messages to her sister discussing how to handle the problem of Felicity’s annoying little sister ruining the wedding photos.

Apparently, Diane had convinced herself that I was deliberately trying to sabotage Felicity’s marriage to her son and that removing me from the equation would solve multiple problems. The detective asked if I wanted a restraining order, and I said yes immediately, not wanting to take any chances that she might try something else if she made bail.

The local news picked up the story, and suddenly I couldn’t go anywhere without people recognizing me as the girl who almost died at her sister’s wedding. My phone exploded with messages from people I barely knew. Everyone wanting details or offering sympathy or asking invasive questions about my relationship with Diane.

I ended up turning my phone off completely and staying with dad at his house while I recovered, sleeping in my old childhood bedroom, surrounded by posters and stuffed animals from a simpler time. Felicity and Jeffree postponed their honeymoon and came over everyday to check on me, bringing food and movies, and just sitting quietly when I didn’t feel like talking.

Jeffree apologized constantly for his mother’s actions, saying he’d known she had control issues, but never imagined she was capable of something like this. He told me they’d cut off all contact with her and were cooperating fully with the police investigation, providing phone records and emails that showed the extent of Diane’s obsession with controlling every aspect of the wedding.

Physical therapy started 2 weeks after I got out of the hospital because the drug combination had done some nerve damage that affected my coordination and balance. I had to relearn how to walk without stumbling and how to hold things without dropping them. Like my brain had forgotten how to send the right signals to my muscles.

The therapist, a woman named Kira with impossibly positive energy, kept telling me I was making great progress, even when I felt like I was moving backward. She explained that the toxins had affected my central nervous system, and it would take months of consistent work to fully recover, if full recovery was even possible. Some days I couldn’t hold a pen to write or a fork to eat, and I’d end up crying in frustration while dad tried to help without making me feel more helpless.

The doctor said I was lucky to be alive and that most people who ingested that particular cocktail of drugs didn’t survive, which made me feel simultaneously grateful and angry that my sister’s mother-in-law had turned me into a cautionary tale. Diane’s preliminary hearing happened 6 weeks after the wedding, and I had to testify about what I remembered from that day.

Her lawyer tried to paint me as an attention-seeking drama queen who’d taken drugs myself to ruin Felicity’s wedding, which was such an absurd claim that several people in the courtroom actually laughed. The prosecutor presented the evidence of Diane purchasing the drugs, researching dosages online, and being witnessed by multiple people tampering with my drink.

They played security footage from the venue, showing Diane taking my champagne flute from a server’s tray, stepping behind a column for 30 seconds, then placing it back on the tray in a specific position. The time stamp matched perfectly with when that tray was distributed to the bridal party, and my seat assignment put me in the exact spot where that doctorred drink would have ended up.

Diane sat through all of this with her arms crossed and her face blank, like she was watching a boring movie instead of evidence of her attempting to murder me. The judge ordered her held without bail until trial, citing the severity of the charges and the premeditated nature of the crime. Social media became a nightmare after the hearing because people started taking sides and creating these elaborate theories about what really happened.

Some blamed Felicity for not protecting me better. Others blamed dad for marrying into a family with someone like Diane. And a disturbing number of people claimed I must have done something to provoke her or that I was lying for attention. I made the mistake of reading through comments on one news article and spent the next hour crying over strangers calling me a liar and a gold digger trying to sue Diane’s family.

Dad eventually blocked all the news sites and social media apps on my phone because I couldn’t stop obsessively checking what people were saying about me. Felicity dealt with her own harassment online with people sending her hateful messages about ruining her mother-in-law’s life and destroying her son’s marriage before it even began.

She ended up deleting all her social media accounts and going completely dark online, which was hard for her because she’d built part of her career on professional networking. The trial itself took 3 weeks and was covered by local news stations every single day. I had to sit in that courtroom listening to Diane’s lawyer try to discredit me by bringing up every mistake I’d ever made, every bad grade in high school.

Every time I’d gotten in trouble as a kid, they tried to paint a picture of me as an unstable attentionseker who’d orchestrated this whole thing to get sympathy and money from a lawsuit. But the physical evidence was overwhelming, and the witnesses were consistent. And on the 10th day of testimony, the jury came back with guilty verdicts on all charges.

Diane showed no emotion when the verdicts were read, just stared straight ahead like she was somewhere else entirely. The judge scheduled sentencing for 3 weeks later and warned Diane’s family in the courtroom to maintain distance from me and Felicity or face contempt charges. Walking out of that courthouse knowing Diane had been convicted felt surreal, like I’d been holding my breath for months and could finally exhale, even though nothing about the situation felt like a win.

Sentencing day arrived with unexpected media attention because Diane’s case had become a bigger story than anyone anticipated. The courtroom was packed with reporters and spectators, and I had to squeeze through a crowd just to get inside. The prosecutor asked for the maximum sentence given the premeditated nature of the crime and the permanent damage done to my health.

I read my victim impact statement with shaking hands, describing how I still couldn’t hold things properly and how I had nightmares about being locked in that storage room dying alone. I talked about losing my sense of safety at family gatherings and how I’d probably never trust a drink I didn’t pour myself ever again.

Diane’s lawyer argued for leniency because she had no prior criminal record and was a respected member of the community, which felt like a sick joke given what she’d done. The judge listened to everything and then sentenced Diane to 18 years in prison with possibility of parole after 12, calling it one of the most disturbing cases of premeditated violence she’d seen in her career.

Diane finally showed emotion then, crying and turning to look at Jeffree in the gallery, but he just stared back at her with no expression before getting up and walking out. Recovery wasn’t a straight line after the trial ended. Some days I felt almost normal, and other days I couldn’t get out of bed without everything spinning.

The nerve damage meant I had permanent tremors in my hands and occasional balance issues that came and went without warning. I had to drop out of community college for a semester because I couldn’t physically write notes or type properly, which put me even further behind Felicity in everyone’s eyes. But she never made me feel bad about it.

Never compared her graduate degrees to my unfinished associates. Just supported me through physical therapy and doctor’s appointments and the endless paperwork that came with being a crime victim. Dad sold his house and bought a new one in a different neighborhood, saying he needed a fresh start without memories of Diane in every room.

We packed up my childhood bedroom together, and I threw away most of my old stuff, wanting to leave that version of myself behind and start over as someone who’d survived attempted murder and lived to tell about it. Jeffree and Felicity’s marriage survived despite everything, though they ended up in intensive couples therapy to deal with the trauma.

Jeffree had to process that his mother had tried to kill his wife’s sister, and Felicity had to work through her guilt about not protecting me when she saw something was wrong during the ceremony. They moved across the country for Jeffrey’s job about a year after the trial, putting physical distance between themselves and the constant reminders of what happened.

We video call every week and they visit for holidays and things feel almost normal until someone mentions the wedding and we all go quiet. They never had a real celebration or reception. Never got the happy beginning they had planned. And I carry guilt about that even though everyone tells me it wasn’t my fault.

The wedding photos that were taken before everything went wrong sit in a box in Felicity’s closet. Never framed or displayed. Just preserved evidence of the last moment before our family changed forever. 2 years after the poisoning, I finally finished my associates degree and transferred to a 4-year university 3 hours away from home.

Starting fresh in a new city where nobody knew my story felt liberating, like I could be someone other than the girl who almost died at her sister’s wedding. I made new friends who never asked about my scars or why my hands shook sometimes, who accepted me as I was without needing to know the before version. I changed my major to criminal justice because the experience with the legal system had shown me how much victims needed advocates who understood what they were going through.

My professors never knew why I was so passionate about victim’s rights or why I volunteered so many hours at the campus legal aid clinic. And I preferred keeping that part of my story private. Dating was complicated because eventually I’d have to explain the tremors and the nightmares and why I wouldn’t drink anything I didn’t open myself.

But the right people understood and the wrong people showed themselves out quickly. Diane sent me a letter from prison about 3 years into her sentence, claiming she’d found religion and wanted to apologize for what she’d done. The return address made my hand shake so badly I dropped the envelope and I didn’t open it for 2 weeks. When I finally read it, the apology felt hollow and performative, full of justifications about being stressed and not thinking clearly and how she never meant for things to go that far.

She asked me to write a letter supporting her parole application when the time came, saying she’d learned her lesson and deserved a second chance. I burned the letter in my apartment’s fireplace and never responded, owing her absolutely nothing after she’d nearly taken everything from me.

My therapist said that was a healthy boundary and I shouldn’t feel guilty about refusing to participate in Diane’s redemption narrative when I was still dealing with the consequences of her actions. Life moved forward in small increments and unexpected ways. I graduated with my bachelor’s degree in criminal justice and got accepted into a good law school with a scholarship that covered most of the tuition.

Dad came to my graduation and cried when I walked across the stage, probably remembering that there was a time when he didn’t know if I’d ever walk again. Felicity and Jeffree had twins that year, a boy and a girl they named after our mother and Jeffrey’s father, deliberately excluding any family connection to Diane.

I flew out to meet them when they were 2 weeks old. These tiny, perfect humans who would grow up never knowing their grandmother and never understanding why. Jeffree still went to therapy to process his mother’s betrayal. Struggling with guilt that wasn’t his to carry, but feeling it anyway. He’d cut off all contact with Diane and legally changed his middle name to remove the family connection, trying to separate himself from her legacy.

The physical tremors in my hands improved with continued therapy, but never completely disappeared. A permanent reminder of how close I came to not being here. I learned to write with the tremors and type around them and eventually stopped being embarrassed when people noticed. My law school classmates thought it was from anxiety or too much caffeine, and I let them believe that rather than explaining the real story.

I specialized in victim advocacy and prosecution work, using my experience to fuel my passion for holding perpetrators accountable. Every case I worked on through my clinical internships felt personal in a way my supervisors noticed but didn’t question. Recognizing that the fire driving my work came from somewhere real and painful, I graduated near the top of my class and got recruited by the district attorney’s office in a major city.

Finally feeling like I’d turned my trauma into something meaningful and useful. Diane became eligible for parole after serving 12 years. And the notification letter arrived at my apartment on a random Thursday morning. My hands shook worse than they had in years as I read that she’d be having a parole hearing in 3 months and victims had the right to submit statements or attend in person.

I called Felicity immediately and we cried together over the phone. Both of us dragged back to that day at her wedding when everything went wrong. We agreed to write statements opposing parole but not to attend the hearing in person, not wanting to see Diane face to face after all these years. Writing that statement took me three weeks and multiple drafts, trying to capture how her actions had permanently altered my life’s trajectory and taken away my ability to ever feel completely safe.

The tremors, the nightmares, the hypervigilance around food and drinks, the years of therapy, the relationships that failed because I couldn’t trust people not to hurt me. All of it traced back to 18 minutes at my sister’s wedding when someone decided I was disposable. The parole board denied Diane’s release, citing the severity of her crime and lack of genuine remorse in her statements.

She’d be eligible to apply again in 2 years, starting a cycle that would probably continue for the rest of her sentence. Jeffrey’s relief was palpable when he called to tell us the news. And I could hear the twins making noise in the background, oblivious to the danger their grandmother represented. We all exhaled together, knowing we had at least two more years before having to face this again.

Two more years of safety before the system made us relive our trauma to convince strangers that Diane should stay locked up. It felt like a punishment for surviving. This constant requirement to prove that what happened to us was bad enough to justify continued consequences for the perpetrator. Now, 6 years after that day, I prosecute criminal cases and fight for victims who can’t always fight for themselves.

My hands still shake sometimes, and I still won’t drink anything I didn’t prepare myself. And I still have nightmares about being locked in dark rooms, unable to breathe. But I’m also stronger than I ever thought possible with a career I love and a life I built from the wreckage of what Diane tried to destroy.

Felicity’s twins call me auntie and have no idea why I flinch when they offer me sips of their juice boxes. Why I always have to watch them pour it first. My sister’s wedding album sits in her closet unopened, a memorial to the celebration that never was, and the innocence we lost that day. Some wounds heal and some just become part of who you are.

and I carry both kinds forward into whatever comes next. Sometimes people ask if I’ve forgiven Diane and I tell them honestly that forgiveness isn’t something she’s earned or that I owe her. She made a choice to poison me and another choice to lock me away while I died and she has to live with those choices just like I have to live with their consequences.

The difference is I didn’t choose this path, but I’m making the most of it anyway, turning my pain into purpose and my trauma into triumph. That’s more than Diane ever did with her freedom and more than she deserves from the life she tried to take from me. My sister’s wedding turned into a crime scene in under 20 minutes, but the aftermath has lasted years and taught me more about human nature and survival than any classroom ever could.

I wouldn’t choose this story if I had the option, but I’m not ashamed of it either. Thanks for hanging out till the end. If you want more stories, make sure to subscribe and leave your take below.

News

My Mom Canceled My Wedding Saying “We’re Not Funding This Circus” — So I…

My Mom Canceled My Wedding Saying “We’re Not Funding This Circus” — So I… The chemical smell of the…

My Younger Brother Texted In The Group: “Don’t Come To The Weekend Barbecue. My New Wife Says You’ll Make The Whole Party Stink.” My Parents Spammed Laughing Icons. I Just Replied: “Understood.” The Next Morning, When My Brother And His Wife Walked Into My Office And Saw Me… She Screamed, Because…

My Younger Brother Texted In The Group: “Don’t Come To The Weekend Barbecue. My New Wife Says You’ll Make The…

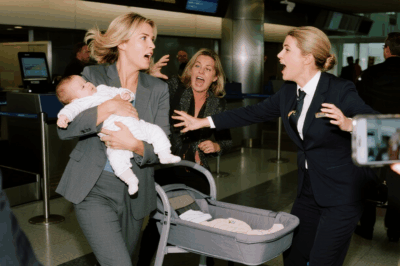

Airport Karen Demands My Baby’s Bassinet — Didn’t Know I’m a Platinum Member

Airport Karen Demands My Baby’s Bassinet — Didn’t Know I’m a Platinum Member You will not believe what happened…

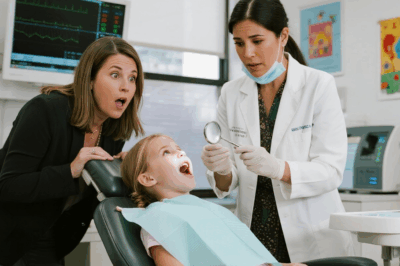

Recently, My Daughter Kept Saying, “My Tooth Hurts,” So I Took Her To The Dentist. While Examining Her, The Dentist Suddenly Fell Silent, His Expression Turning Grim. “Mom, Look At This…” I Glanced Into My Daughter’s Mouth And Gasped. The Dentist Handed Me Something Unbelievable.

Recently, My Daughter Kept Saying, “My Tooth Hurts,” So I Took Her To The Dentist. While Examining Her, The Dentist…

On My 29th Birthday, My Parents Withdrew $2.9 MILLION That I Saved. But Little Did They Know, They Fell Into My Trap…

On My 29th Birthday, My Parents Withdrew $2.9 MILLION That I Saved. But Little Did They Know, They Fell Into…

“Can You Even Afford To Eat Here?” My Sister Mocked, And My Dad Laughed. Then The Waiter Walked Over With A Smile…

“Can You Even Afford To Eat Here?” My Sister Mocked, And My Dad Laughed. Then The Waiter Walked Over With…

End of content

No more pages to load