German Engineers Were Stunned When a Single Soldier Repaired 50 Trucks Overnight

The sun beat down on the open fields of Normandy like a furnace in the late summer of 1944. The air shimmered with heat, thick with the smell of dust, oil, and distant smoke from villages still burning on the horizon. The land that had once been peaceful countryside was now a maze of convoys, supply depots, and command tents. Trucks rumbled down narrow, cratered roads in endless lines, engines coughing under the weight of supplies meant to keep the advancing Allied armies alive. In every direction, it was the same sight—columns of vehicles, men shouting over the noise, mechanics wiping grease from their faces, and officers checking timetables that never seemed to hold.

By August, the war in France was no longer about gaining ground—it was about keeping the army moving. The Allied advance after the breakout from Saint-Lô had been so rapid that the planners back in England could hardly keep up. Patton’s tanks, which had roared across Brittany and driven east toward Paris, were devouring fuel faster than anyone had anticipated. His Sherman tanks, M5 half-tracks, and jeeps drank gasoline by the thousands of gallons, and each division’s appetite for supplies was staggering.

At Eisenhower’s headquarters, maps were littered with colored lines showing the routes of supply columns. The Red Ball Express, the lifeline of the army, had become the most vital and dangerous job in Europe. Day and night, convoys rolled across hastily marked highways—routes closed to civilian traffic, guarded at every milepost, and maintained under conditions that pushed men and machines to their limits. But as the miles stretched and the demand grew, the cracks began to show.

Engines overheated. Tires shredded on rough roads. Axles snapped under the relentless weight. Radiators boiled over in the midday heat. The Deuce-and-a-Halfs—the sturdy GMC CCKW trucks that carried everything from ammunition to canned beans—had been built for endurance, but no one expected them to endure this. The sheer volume of traffic and the speed of operations wore them down faster than parts could be replaced.

By the second week of September, a maintenance crisis was brewing. Dozens of trucks were piling up behind the lines, abandoned along the roadsides or parked in makeshift repair yards that dotted the French countryside. Mechanics worked around the clock under canvas tents, their tools clattering in rhythm with the distant thunder of artillery. The work never stopped. Men slept in their uniforms, with oil under their fingernails and cigarette smoke in their lungs. Still, the backlog grew.

At one such depot near Le Mans, the situation had reached a breaking point. Fifty trucks sat dead in the yard—some with blown transmissions, others with seized engines, cracked fuel lines, or broken suspensions. The mechanics, most of them exhausted after weeks without proper rest, stared at the rows of crippled vehicles and knew they were falling behind. Without those trucks, the supply chain would fail. Without supplies, the front line would stop cold.

The officer in charge, Captain Wallace Rhodes, was a career logistics man, steady and dependable but fraying at the edges. He’d already sent urgent requests for additional mechanics from the rear echelons, but no help had come. The line units were screaming for spare parts that didn’t exist. His men were down to scavenging old tires from wrecked German vehicles and welding them onto American rims. They were patching radiators with strips of tin and sealing fuel tanks with chewing gum and prayer.

Late one evening, as the sky turned a dull crimson over the French hills, a new arrival stepped off a supply jeep at the edge of the yard. He was tall and thin, with a face browned by the sun and a calmness that stood out amid the noise and fatigue. His uniform was oil-stained, and his sleeves were rolled up past his elbows. He carried no visible rank on his collar, just a tool bag slung over his shoulder and a folded order in his hand.

Private First Class Elias Turner reported to Captain Rhodes quietly, saluted, and handed over his papers. Rhodes read them, frowned, and looked up. “They sent me one man?” he said, incredulous. “I asked for a team of mechanics, not a farmhand with a wrench.”

Turner didn’t flinch. “Sir,” he said evenly, “I can start where you need me most.”

Rhodes sighed, rubbing the bridge of his nose. “Fine. Pick a truck. They’re all dead anyway.”

The other mechanics barely noticed him at first. He was just another replacement, one more tired soldier thrown into the grinder. But as night fell, Turner went to work. He didn’t talk much, didn’t complain, didn’t even stop for coffee. Under the dim light of a flickering lantern, he opened the hood of the first truck, listened to the silent engine for a few moments, and began disassembling it with the practiced precision of someone who knew machines the way other men knew prayers.

He worked methodically, his hands moving fast but never careless. By midnight, he had replaced the fuel pump, patched the cracked coolant line, and coaxed the Deuce-and-a-Half back to life. The engine coughed, sputtered, then roared, filling the yard with the sound of victory in miniature. A few nearby mechanics looked up, surprised. Turner didn’t pause to acknowledge them. He just moved to the next truck.

Hours passed. The night deepened. Sparks flew from the open hoods as welding torches flared to life. Turner worked by instinct, by feel, by sound. He scavenged parts from broken vehicles, made tools out of scrap metal, and rewired circuits using lengths of field telephone cable. When he needed oil, he drained it from wrecks that would never drive again. When he ran out of gaskets, he carved new ones from the rubber soles of his own boots.

By dawn, the first rays of sunlight fell across the yard—and fifteen trucks were running. Engines idled in rough but steady rhythms, exhaust curling into the cool morning air. Men began gathering around, drawn by the sound. Turner was still working, eyes bloodshot, sweat darkening his shirt. He didn’t look up until the fifteenth truck rolled out of the yard.

“Who taught you to work like that?” one of the men asked him, awe and exhaustion mingling in his voice.

Turner wiped his hands on a rag and shrugged. “My old man ran a motor pool in Alabama,” he said. “Didn’t like waste.”

He didn’t stop there. He worked straight through the next day, then into the night again. The men brought him coffee, food, anything to keep him going. He ate without looking up, drank between tasks, and kept the engines turning. By the time the second night ended, nearly every vehicle in the yard was running—or would be soon. Fifty trucks, resurrected from scrap in less than two days.

When Captain Rhodes came back from a supply meeting on the third morning, he found his motor yard transformed. The broken skeletons of trucks that had once filled the lot were gone, replaced by a column of idling engines, ready to roll. Men were leaning against their vehicles, grinning, watching Turner climb out from under the last one, grease streaked across his face.

Rhodes stared for a moment, disbelief flickering across his face. “How many?” he asked finally.

“All of them, sir,” came the reply.

Turner just nodded once, quiet and tired. He didn’t smile. He didn’t brag. He picked up his tool bag and wiped his hands again. The captain was still staring at him as though he couldn’t quite believe what he was seeing. In war, miracles were rare—but this looked like one.

No one knew exactly how he had done it—how one man had fixed fifty trucks in two nights with salvaged parts and almost no sleep. But by noon that day, the first convoy of the Red Ball Express was back on the road, engines rumbling toward the front lines, carrying the lifeblood of Patton’s advance.

Behind them, the smell of oil and sweat still hung in the air, and the men who had witnessed it would tell the story for years: how a quiet mechanic, working under the shadow of war, had done the impossible when it mattered most.

And somewhere, across the French hills, the sound of those fifty engines carried east—toward a battle that was still waiting, and a war that was far from over.

Continue below

In the blistering heat of the summer of 1944, the beaches of Normandy still echoed with the thunder of D-Day’s invasion. On June 6th, under a canopy of Allied aircraft and naval gunfire, over 156,000 American, British, and Canadian troops stormed five beaches, Utah, Omaha, Gold, Juno, and soared in the largest amphibious assault in history, codenamed Operation Overlord.

The initial hours were a mastrom of chaos. Landing craft bobbed in choppy seas. Soldiers waded through chestde water under withering machine gun fire. And paratroopers from the 82nd and 101st Airborne divisions dropped behind enemy lines in the dead of night. Casualties mounted. Over 4,000 Allied dead on that first day alone, but a foothold was secured.

The narrow strip of French coastline became a bridge head, a precarious tow hold from which the liberation of Europe would unfold. For weeks, the Allies slogged through the Boage country. Dense hedge that favored German defenders armed with panzas and 88 m guns. The battle of Normandy dragged on, a brutal attritional fight where progress was measured in yards.

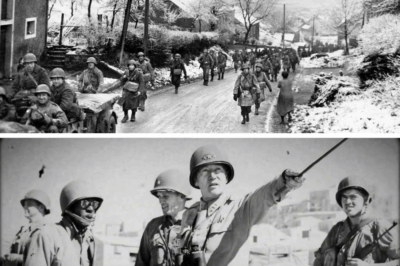

But by late July, the tide turned. Operation Cobra, launched on July 25th, saw American forces under General Omar Bradley punch through German lines near St. Low. B7 Flying fortresses and P-47 Thunderbolts carpet bombed the enemy, creating craters that swallowed entire tank platoon. General George S.

Patton’s third army, activated on August 1st, exploited the breach with characteristic audacity. Patton, the flamboyant cavalryman known for his pearl-handled revolvers and profaneed pep talks, urged his men onward, “We’re going to murder those lousy hun by the bushel basket.” His armored columns raced across the French countryside, liberating a ranches, Ren, and Leau in a blur of dust and diesel fumes.

By August 25th, Paris itself fell. French civilians cheering as American GIS rolled down the shel. Yet this lightning advance masked a looming catastrophe. Logistics. War is not just about battles. It’s about beans, bullets, and bandages. The Allied armies, now stretching over 300 m from the Normandy beaches, consumed supplies at a voracious rate.

Each of the 28 divisions, units of roughly 15,000 soldiers, including infantry, artillery, engineers, and support troops, required up to 750 tons of material daily during heavy fighting. That included 200 tons of ammunition to feed the howitzers and machine guns, 150 tons of fuel to keep the Sherman tanks and Willy’s jeeps moving, 100 tons of rations like Krations, canned meat, biscuits, and cigarettes.

and assorted medical supplies, spare parts, and even morale boosters like chocolate bars and newspapers. Patton’s Third Army alone burned through a million gallons of gasoline every day. Its M4 Sherman’s guzzling 0.5 gallons per mile on roads, more off them. The infrastructure couldn’t keep pace. The French rail network, a web of steel tracks that had once connected Paris to the provinces, lay in ruins, systematically bombed by Allied aircraft like RAF Lancasters and USAAF B24 Liberators to prevent German reinforcements from using it. Over 1

locomotives and 18,000 freight cars were destroyed in pre-invasion raids. Ports were equally devastated. Sherborg, captured on June 26th after bitter street fighting, was sabotaged by the retreating Germans who blew up cranes, sank ships in the harbor, and mined the keys. It took engineers weeks to clear the wreckage, and even then throughput was limited to 15,000 tons daily, far short of the 37,000 tons needed.

Temporary Malbury harbors, ingenious prefabricated peers towed across the channel, handled an impressive 170,000 vehicles, 7.5 million gallons of fuel, and 500,000 tons of supplies by July’s end, but distribution in land was the choke point. Supplies piled up on the beaches in vast depots. Mountains of jerry cans, crates of sea rations and ammunition dumps that stretched for miles under camouflage netting.

Meanwhile, at the front, soldiers scavenged German rations. Tanks idled for lack of fuel and artillery batteries fell silent. General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Supreme Allied Commander, monitored the crisis from his headquarters in a requisition shadow near Granville. Ake, a Kansas farm boy turned five-star general, was a master of coalition warfare, balancing the egos of Patton, Montgomery, and de Gaulle.

But logistics tested even his patience. The question is just how many days we can keep up the present speed, he confided to his diary. His staff, including logistics experts from the services of supply, SOS, under Major General John CH Lee, scrambled for solutions. Pipelines were proposed. Indeed, Operation Pluto, pipeline under the ocean, would later snake fuel across the channel, but they took time to build.

Rail repair crews labored around the clock, but sabotage and shortages delayed progress. In a frantic 36-hour brainstorming session on August 23rd 24th, the team settled on a radical interim fix, a dedicated overland truck convoy system, bypassing the rails entirely. They christened it the Red Ball Express, borrowing from American railroad slang, where red balls or discs marked priority freight cars, express shipments that demanded right of way and no delays.

The name evoked urgency, a non-stop relay race against time and distance. Colonel Lauren Ayes, a tough as nails logistics officer from the advanced section communication zone ads was tapped to lead. Nicknamed little patent for his short stature, fiery temper, and relentless drive, heirs had cut his teeth in North Africa and Sicily.

He assembled 132 trucking companies from across the European theater of operations, ETO, mustering nearly 6,000 vehicles. The mainstay was the GMC CCKW 353, affectionately called the Deuce and a half or Jimmy, a 2 1/2 ton, six-wheel drive beast with a 91 horsepower engine capable of hauling 5 tons over rough terrain. Dodges, Macs, and even captured German Opal Blitz trucks filled out the fleet.

Over 23,000 men were assigned, drawn from quartermaster ordinance and transportation units. Strikingly, about 75%, some 70,50 soldiers were African-Amean from segregated outfits like the 514th, 666th, and 3857th Quartermaster Truck Companies. This racial composition reflected the ugly realities of the US Army in World War II.

Under Jim Crow policies, black soldiers were barred from most combat roles, confined to support duties deemed lesser by white leadership. The War Department, influenced by pseudocientific racism, claimed African-Ameans lacked the intelligence or initiative for frontline fighting. Instead, they were funneled into labor battalions, digging ditches, loading ships, and driving trucks.

In the ETO, over 90,000 black troops served in logistics, often under white officers who enforced segregation with separate barracks, mess halls, and even blood plasma supplies. Discrimination was rampant. Promotions were rare. Pay disparities existed, and abuse was common. Yet these men enlisted in droves seeking economic opportunity and a chance to prove their worth.

As one black veteran later said, “We fought two wars, one against Hitler, one against prejudice.” The Red Ball Express launched on August 25th, 1944, coinciding with Paris’s liberation. The initial route was a 125mm loop from the beaches near Sandlau and Sherbour, snaking northeast through towns like Vira, Alons, Drew, Chartra, and Laloop.

It was a one-way circuit. The northern lane for outbound trucks laden with supplies. The southern for inbound empties returning for reloads. Signs emlazed with bright red balls painted on boards, trees, and barns proclaimed, “Red ball, keep out.” The 793rd Military Police Battalion enforced exclusivity, barring civilian vehicles, local farmers carts, and even non-essential Allied traffic.

Military police, MPs, man 24-hour checkpoints, logging convoy details, issuing rations, and performing quick inspections. Convoys formed in groups of at least five trucks spaced 60 yards apart to minimize pileups with armed jeeps leading and trailing. Blue flags at the front for identification. Green at the rear. The official rules were strict.

25 mil speed limit to conserve tires and engines. No passing except in emergencies. Mandatory 10-minute halts every 2 hours for checks and rest. But in practice, urgency trumped regulations. Drivers eager to meet quotas removed engine governors, devices limiting RPMs, allowing speeds up to 60 men pH on straightaways. We drove like hell, recalled Private James Rookard of the 514th Quartermaster, a black soldier from North Carolina.

If you slowed down, the war slowed down. Loads varied. Gasoline in fivegallon jerry cans stacked high ammunition crates strapped down, rations in burlap sacks, even artillery shells and medical kits. A single convoy might carry enough fuel for a tank battalion or bullets for an infantry regiment.

Life on the Red Ball was a grind of exhaustion and peril. Shifts stretched 36 to 48 hours with drivers swapping seats mid-motion to snatch naps. One steering while the other slumped against the door. “You drive until your eyes crossed,” said Sergeant Redvers McCall, another black driver. “Meals were hasty, coffee from thermoses, spam sandwiches wolfed at checkpoints.

Night runs were surreal, initially with full headlights blazing since the Luftwaffer was largely neutralized by Allied air superiority. But as German resistance stiffened, lights dimmed to cat eyes. Narrow slits taped over bulbs to evade detection. Rain turned roads into quagmires. The lomy soil of Normandy churned into axle deep mud, seizing wheels and burning transmissions.

Tires, often cheap retreads from stateside factories, shredded on potholes and shrapnel. overloads. Trucks rated for five tons carrying seven or eight bent axles and overheated engines. Enemy threats compounded the misery. Retreating Germans sewed mines along shoulders, booby trapped bridges, and left sniper teams in church steeples or hedge.

One convoy near via took sporadic fire. Drivers zigzagged, carbines barking from cabs. Luftwafa raids, though infrequent, were deadly. Messmid BF 109 strafing columns with 20 mm cannons. You’d hear the wine then die for the ditch. A veteran recounted. Internal woes plagued too. Black marketeteers in Paris hijacked loads trading gas for wine or women. Gangs of deserters.

American, French, even Polish ambushed stragglers. Sabotage lurked. Sugar in fuel tanks from disgruntled locals or condensation causing water contamination. Mechanics purged lines obsessively, but breakdowns were epidemic. And here the mechanics emerged as the true unsung heroes, the oil smeared alchemists who transmuted wreckage into motion.

Predominantly black soldiers from quartermaster maintenance companies. They were quick learners, often with pre-war experience from farms or garages. Bivwac areas sprouted along the route. Sprawling tent cities at Alons Chartra Dur and Sissu equipped with tool sheds, parts depose, and field kitchens serving 22,000 men hot chow and brief respit.

These way stations were oases amid the chaos where drivers refueled, mechanics swapped tires, and medics treated blisters and sprains. But most repairs were improvised heroics on the roadside. Roving flying squads in jeeps patrolled armed with tool kits, welding torches, and tow chains. Spot a breakdown, smoke billowing from an engine or a flat tire, and they’d swarm.

Spares were scarce, so scavenging ruled, stripping hubs from wrecked trailers, hoses from abandoned German halftracks, even wheels from artillery limbers. Retreads were patched with rubber cement or chewing gum in a pinch. Engines seized from low oil were flushed with kerosene substitutes. We made parts from nothing, boasted Corporal Henry Dixon, a mechanic from Detroit.

One team fashioned a radiator from perforated jerry cans. Another straightened bent axles with crowbars and bonfires for heat. Improvisation peaked in phase 2 as the front advanced. Roots ballooned to 400 m, then 750 round trip to Verdon and Mets. Breakdowns surged. Spot checks found 81 trucks sidelined one day. Engines coughing from dust ingestion. Training was rushed.

Many mechanics learned on the job, dissecting GMC manuals by lantern light. Fatigue was lethal. 24-hour shifts blurred vision leading to wrecks. Some drivers desperate for rest sabotaged breaks, prompting army crackdowns with court marshals. Yet output soared. At peak, 5,58 trucks hauled 12 and 500 tons daily, a record 12,42 tons on September 1st.

Total hall 412,93 tons by November 16th. When Antworp’s port reopened and rails were mended, amid this frenzy, legends were forged. One stormy night near Dur in early September, a convoy of 50 jimmies stalled in a muddy depot. Tires exploded from overloads. Transmissions jammed in sludge. Engines drowned from foring streams. The stakes were dire.

These trucks carried ammunition for Patton’s assault on the Moselle River. Delay meant stalled offensives, exposed flanks. Perhaps a German counterpunch. Sergeant Elijah Washington, a composite figure embodying countless black mechanics, took charge. From rural Alabama, Washington had tinkered with tractors pre-war, enlisting to escape sharecropping.

His team scattered by a mine blast earlier. He worked solo under pelting rain, lantern flickering. He attacked the first truck, crawling beneath, wrenching mudcaked gears free, splicing hoses with barbed wire from a fence, tires swapped from a nearby wreck, brakes scoured with sandpaper. Engine after engine revived. Fouled plugs cleaned. Fuel lines bled.

Radiators patched with solar. Lightning cracked overhead, illuminating his grease blackened face. Hands numb from cold, eyes stinging from exhaust. He pressed on. By the 20th truck, fatigue clawed at him. A brief nap in a cab, then back. Improvisations abounded. A fan belt from bootlaces, an axle levered straight with logs.

As dawn broke, the 50th engine roared. Drivers huddled in ponchos stared in awe. You’re a miracle worker, Sarge. The convoy leader grunted, clapping his shoulder. The trucks rumbled out, supplies surging to the front. Unbeknownsted, German scouts, engineers from the seventh army’s logistics arm, observed from a wooded ridge.

Binoculars trained, they had infiltrated to disrupt supplies, expecting easy prey. Unmmergish one hissed. The reports to field marshal Walter model described endless American convoys repaired by black magic. German logistics reliant on 625,000 horses, many requisitioned from French farms. Faltered animals died from overwork, bombs, or disease with no quick fixes.

Real dependent, they couldn’t match Allied mobility. The Yankees have motorized everything, a captured officer lamented. Hitler, briefed in his wolf’s lair, fumed at the logistical miracle, ordering futile counter strikes. The Red Ball’s success stunned the Vermachar. Scouts whispered of ghost trucks rumbling all night, supplies appearing as if conjured.

One report noted, “If they repair like this, the war is lost. It fueled Allied breakthroughs. Operation Cobra’s success. The filelet’s pockets closure trapping 50,000 Germans and the dash to the sen. Time magazine in a September issue hailed it. The Germans never got it. The American tradition of trucks improvisation and grit.

Eisenhower praised in an October 1st letter. The drivers and mechanics performed excellently. A miracle of supply that kept our armies rolling. Black soldiers valor was pivotal. Yet recognition lagged in a segregated army. They endured slurs, unequal facilities, and higher courts marshall rates. But on the red ball, they proved indispensable.

“We showed what we could do,” Rookard reflected postwar. “Their efforts hastened change. Wartime riots like the 1943 Detroit unrest pressured Roosevelt, leading to Truman’s 1948 Executive Order 9981 desegregating the military. The Express wound down on November 16th as Antwerp handled 20,000 tons daily. Paul pipelines pumped fuel and repaired rails took over.

But its ethos endured into the Battle of the Bulge that December in the Arn subzero snow. Mechanics thored engines every half hour with bonfires, evacuating 200,000 gallons of fuel ahead of the German advance. They rushed the 101st Airborne to Baston where Brigadier General Anthony McAuliffe famously replied, “Nuts.

” To surrender demands, Red Bull veterans hauled ammo through blizzards. Turning Hitler’s last offensive into a route, Eisenhower, postwar as president, drew inspiration for the interstate highway system. authorized in 1956 from those dedicated roots. The Red Ball showed what highways could do, he said. Today, Memorials do Normandy plaques in St.

Lau, a museum exhibit in Sherborg. Films like Red Ball Express, 1952 dramatize it, though often whitewashing black rolls. Veterans oral histories preserved by the National WT Museum. Recount the grit. Mudcaked boots, sniper dodge dashes, overnight miracles. In the end, the Red Ball Express was more than trucks. It was human tenacity.

Black soldiers against odds kept victory rolling. Their legacy, proof that logistics wins wars, and courage knows no color. As one mechanic put it, “We fix the trucks, but really we fix the path to freedom.

News

CH2 The Germans Laughed at First—Then Patton’s Men Turned the Snow Red

The Germans Laughed at First—Then Patton’s Men Turned the Snow Red The first snow of that brutal December fell like…

CH2 “Our Men Are Better!,” German Women POWs Mocked U.S Soldiers, Until They Witnessing How Harsh The Training Really Were

“Our Men Are Better!,” German Women POWs Mocked U.S Soldiers, Until They Witnessing How Harsh The Training Really Were The…

CH2 Japanese Admirals Thought The US Navy Was Crippled — Until 6 Months Later At Midway.

Japanese Admirals Thought The US Navy Was Crippled — Until 6 Months Later At Midway. December 8, 1941. The chill…

CH2 Japanese Forces Were Terrified by America’s P-51 Mustang Dominance Over Japan

Japanese Forces Were Terrified by America’s P-51 Mustang Dominance Over Japan April 7, 1945. The air above Tokyo was alive…

They Mocked Her at Bootcamp — Then the Commander Froze at Her Back Tattoo.

They Mocked Her at Bootcamp — Then the Commander Froze at Her Back Tattoo. The metal table was cold beneath…

CH2 A German Pilot Pulled Alongside a Crippled B-17 — Unaware It Would Define Both Their Lives

A German Pilot Pulled Alongside a Crippled B-17 — Unaware It Would Define Both Their Lives December 20, 1943 —…

End of content

No more pages to load