Following my husband’s death, my daughter looked me in the eye and said, “If you don’t start working, you’ll have no place to live.” A few years later, I came back—and made her regret every word….

When my husband died, I thought the grief would be the hardest part. But it wasn’t. It was the moment my daughter looked me in the eye and said, “Either you work, or you’re out on the street.” That was when I truly learned what loneliness meant.

I’m Carol Simmons. Sixty-three years old, born and raised in Ohio. I was a wife for thirty-eight years. A mother to one. And now, I suppose, a widow with nowhere to go.

My husband, Greg, passed suddenly from a heart attack in early March. One minute he was making his terrible scrambled eggs on a Saturday morning, the next, he was gone—just like that. We had savings, but not much. He had been the breadwinner, working as a warehouse manager until retirement, and I was always the homemaker. It worked for us. Until it didn’t.

After the funeral, everything moved quickly. My daughter, Lisa, who had moved to Raleigh years ago, stayed behind for a week to “help sort things out.” What she really did was go through papers, make suggestions about selling the house, and ask me what I planned to do next. Her tone was businesslike, impatient.

“I can’t afford to support you, Mom,” she told me on day six. “I have two kids and a mortgage. You’ll have to get a job or figure something else out.”

I stared at her. “Lisa, I haven’t worked in almost forty years. What kind of job could I possibly do?”

She shrugged. “There’s remote work, call centers, grocery stores. Plenty of older people work. You can too.”

I was stunned. This was my daughter—the baby I raised, the girl I read to every night, who cried when I dropped her off at kindergarten. Where was the warmth? The empathy? ….

Continue below

Following my husband’s death, my daughter looked me in the eye and said, “If you don’t start working, you’ll have no place to live.” I remember the moment like it happened yesterday: her words hanging in the air, sharp and unforgiving, slicing through my grief. A few years later, I came back—and I made her regret every single word.

When Greg died, I thought grief would be the hardest part. I thought losing the man I had spent thirty-eight years with, the man whose laugh filled the kitchen every morning and whose hand I held when the world felt too heavy, would leave a void too deep to bear. But it wasn’t grief that shattered me. It was the moment my daughter, Lisa—the child whose tiny hand I had held through scraped knees, school plays, and first heartbreaks—looked me in the eye and said with cold certainty, “Either you work, or you’re out on the street.” That was the day I truly understood what loneliness meant.

I’m Carol Simmons. I’m sixty-three years old. I was born and raised in Ohio. I was a wife for thirty-eight years and a mother to one daughter, and now, I suppose, a widow with nowhere to go. My identity had always been wrapped up in caring for my family, keeping a home, remembering the little things that made our lives smooth and predictable. Birthdays, anniversaries, grocery lists, holiday dinners—these were my domain, my contribution, my pride. I had not imagined that the world would suddenly ask for something completely different of me: independence, financial responsibility, resilience. At an age when most people think about slowing down, I was being told to start over.

Greg passed suddenly from a heart attack one chilly Saturday morning in early March. He was making his terrible scrambled eggs—the ones that always came out dry and clumpy, but that I ate anyway just to humor him—when he clutched his chest and collapsed. One minute he was standing in our modest kitchen, telling me a joke about the neighbor’s cat, and the next, he was gone. Just like that. I could feel the weight of a lifetime of plans, shared routines, and comfort crash down on me all at once. We had some savings, but it wasn’t much. He had been the breadwinner, working as a warehouse manager until retirement. I had always been the homemaker. It worked for us, until it didn’t.

After the funeral, life accelerated in a blur of paperwork, condolences, and phone calls. Lisa flew in from Raleigh, claiming she wanted to “help me sort things out.” But it didn’t feel like help. It felt like scrutiny. She went through our papers, sifted through Greg’s tools and bills, suggested selling the house, and asked what my next plan was. Her tone was brisk, businesslike, and impatient, like she was handling an estate rather than her mother’s grief.

“I can’t afford to support you, Mom,” she said on the sixth day, leaning against the counter, her arms folded. “I have two kids, a mortgage, and my own life. You’ll have to get a job or figure something else out.”

I froze. “Lisa, I haven’t worked in almost forty years. What kind of job could I possibly do?”

She shrugged. “There’s remote work, call centers, grocery stores. Plenty of older people work. You can too.”

I stared at her, the words refusing to make sense. This was my little girl—the one I had read to every night, the one who cried when I dropped her off at kindergarten, the one whose scraped knees I had kissed better countless times. Where was the warmth? The empathy? The human connection? Instead, there was a practicality so cold it left me hollow.

I didn’t argue. Maybe I should have. Maybe I should have told her that grief is a process that doesn’t follow a timetable and that her words cut deeper than she could imagine. But I was too tired. Too broken. So after she left, I sat in the silence of the empty house, staring at Greg’s chair in the kitchen, the one place where he had always sat, and I cried until I could no longer draw breath.

Grief couldn’t pay the bills. The mortgage was manageable for two retirees. Alone, it became a mountain I couldn’t climb. My Social Security check barely covered utilities and groceries, and I had no other income. No one to lean on. No one to comfort me through the nights.

Three weeks later, I found myself standing in line at the local job center, feeling as though I was wearing someone else’s skin. I was the oldest person there by at least twenty years. Young counselors with cheerful haircuts and earbuds glanced at me as I shuffled to the desk. The career counselor, Troy, looked barely old enough to drive. He tapped on his keyboard as I sat across from him, pretending to exude confidence while my insides quivered.

“Have you worked before?” he asked.

“Not since 1987,” I said.

He paused, glancing at me as if to decide whether to invest effort in helping me. “Okay. Let’s see… Any computer experience?”

“I can use email. I shop online.”

He nodded politely, but I could feel his skepticism. I knew exactly what he was thinking: She’s too old. She won’t make it.

Eventually, he found a lead: a part-time position as a receptionist at a small medical clinic, answering phones and scheduling appointments. The pay was just above minimum wage, but it was something. I applied. Two days later, I had an interview. I wore a blouse and a skirt that hadn’t seen daylight in years, straightened my hair, and practiced my smile in the bathroom mirror. The office manager was kind, but there was a tightness in her expression, a politeness that reeked of caution.

“We’ll let you know,” she said.

They didn’t.

Five more applications, five more rejections, five more emails that read, We regret to inform you… Each one hit like another tiny death. I stopped checking my inbox altogether. My confidence was crumbling, but I refused to give up. I reminded myself that this wasn’t about pride or stubbornness. It was survival.

In early May, desperation forced me to make hard decisions. I began selling anything I could—Greg’s tools, old furniture, my wedding china. Each item I sold felt like a piece of my past being packaged and handed to strangers. The hardest part was listing the house. Every corner held memories: the wallpaper in the kitchen where Greg had hung our wedding picture, the living room rug where Lisa had learned to walk. But I did it anyway. Lisa didn’t comment much when I told her. Maybe she was relieved. Maybe it didn’t matter to her at all.

By June, the house was under contract. I moved into a small studio apartment on the edge of town. It smelled like mildew and cheap air freshener, but it was mine. My sanctuary, however humble, gave me the first taste of autonomy I had felt in years.

In a moment of quiet desperation, I wandered into the public library and asked the librarian if they offered any classes for seniors. She smiled—a warm, understanding smile that I hadn’t seen in months. “Actually, we do. Computer skills, job readiness, even beginner Excel. Want me to sign you up?”

I nodded, my heart pounding. Terrified, but for the first time in months, I felt a flicker of hope.

Learning Excel at 63 should have broken me, but it didn’t. Instead, it opened a door I hadn’t known existed. The library became my sanctuary. Every Wednesday and Friday, I took the bus downtown, my cracked leather notebook in my tote and a dollar coffee in hand. The computer class was small—five students, all over 55. Ms. Henry, our teacher, had silver hair and a no-nonsense voice. She never spoke down to us, and it made all the difference.

We started with basics: saving files, typing, online searches, avoiding scams. Then Google Docs. Then spreadsheets. One day, she showed us how to use Zoom. “You never know,” she said, “some of you might end up working remotely.” I laughed. Me? A trembling widow with a résumé starting in 1973, working remotely? But I practiced every night.

Around the same time, I picked up a part-time job at a dry cleaner three blocks away. The pay was lousy, and the work—standing on my feet for six hours, tagging shirts, running the register—was exhausting. But it was something I could do. And for the first time in months, people smiled back at me. I remembered names. Faces. Little details. And I felt human again.

One Saturday morning, while waiting for the bus, I met Angie. Short, curly hair, faded college hoodie. “I’ve seen you at the library,” she said. “You in the job program too?”

I nodded. She had once been a legal secretary and was now pivoting to virtual assistant work after a layoff. “It’s not glamorous,” she said, “but it’s flexible and all online. You should check it out.”

The idea lodged itself in my mind. That night, I Googled “virtual assistant jobs for seniors” and discovered contract gigs—email sorting, calendar management, customer service. It sounded possible. Achievable. I signed up.

By late summer, I landed a remote role with a small furniture company in Vermont, managing appointment bookings and monitoring their inbox. $17 an hour. I nearly cried at my first paycheck.

I quit the dry cleaner in September. Not because I hated it, but because I didn’t need it anymore. Confidence grew as I added clients—writing invoices for a florist in Portland, creating social media posts with Canva for a small boutique. I worked 25 hours a week at my folding table by the window, a plant I had kept alive since Greg’s death thriving beside my monitor.

In October, Lisa called. Her voice cautious, uncertain. “Hey Mom, just checking in.”

“I heard you sold the house. Are you… okay?”

I told her about the jobs, the classes, the clients. I didn’t brag, but I didn’t downplay it either. Silence followed. Then finally, “I didn’t think you’d actually do it. I’m sorry for what I said.”

I swallowed hard. “It wasn’t easy. But I’m not on the street.”

A pause. “Would you want to visit for Thanksgiving? The kids miss you.”

I told her I’d think about it. I didn’t say yes immediately. I wanted to, but I had learned something invaluable: I made choices now because of strength, not guilt.

By December, my life had shifted completely. Steady income, friends at the library, a laptop I had bought with my own money, a new sense of purpose. I wasn’t the woman I used to be. I was something stronger, tougher, and entirely my own. I had fallen, been pushed, and stood up.

Not because someone saved me. But because I saved myself.

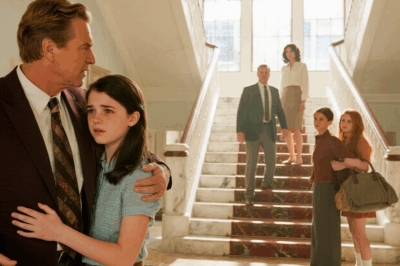

And when Thanksgiving arrived, I did go to Raleigh—not as a dependent or a ghost of my old self, but as a woman who had survived, who had rebuilt. And when Lisa opened the door, a little hesitant, I felt no apology or bitterness. Instead, I felt pride. Pride that I had walked through fire and come out whole. And as we hugged, I realized something profound: the woman my daughter had doubted was stronger than either of us had imagined.

By the end of the holidays, I had made plans to expand my remote work, volunteer at the library, and even explore community college courses in marketing and design. Life was no longer about survival—it was about growth, reinvention, and finally, freedom. I had been a homemaker, a widow, a struggling senior trying to find her place. Now I was Carol Simmons, the woman who refused to be left behind, the woman who could thrive at any age.

News

I Woke Up on Thanksgiving to an Empty House—My Whole Family Left for a Luxury Trip Without Me

I Woke Up on Thanksgiving to an Empty House—My Whole Family Left for a Luxury Trip Without Me I woke…

CEO Fired Every Nanny Until Her Daughter Slept Peacefully Holding the Single Dad Janitor’s Keychain!

Vanessa Caldwell stood frozen in the doorway, her manicured hand clasped over her mouth in disbelief.There, curled up on the…

“‘She’s my daughter,’ my father said—and the world cracked open: the secret child, the silent mother, and the betrayal that shattered everything.”

‘She’s my daughter,’ my father said—and the world cracked open: the secret child, the silent mother, and the betrayal that…

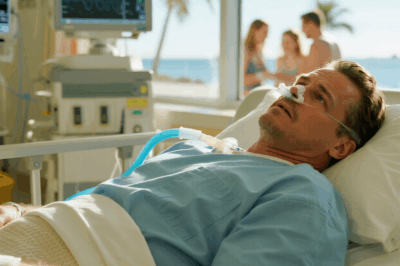

“Left to die while they vacationed: ICU patient secretly plots revenge, exposing family’s betrayal, lies, and hidden greed in shocking twist.”

I was in the ICU when my family boarded a plane for paradise. When they finally walked back into the…

“Daddy, that waitress looks exactly like Mommy!” The millionaire turned in shock his wife had passed away years ago.

James Whitmore was a name everyone in Manhattan’s business circles knew. By the age of 45, he had built a…

Rich Man’s Arrogant Son Kicked the Maid’s Bucket—Then Froze When He Learned Who She Really Was

The lobby of Caldwell Enterprises gleamed like a palace. Italian marble floors, golden chandeliers, and polished brass elevators—all shouting luxury…

End of content

No more pages to load