Family of Four Vanished on Road Trip, 2001 — 23 Years Later Hiker Found This…

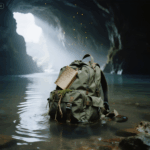

On June 15, 2024, wildlife photographer Eric Chen set out into the deep timber of Idaho’s Caribou-Targhee National Forest, a sprawling, wild landscape of pine ridges and hidden valleys that stretched for miles without roads or cell signal. He was there for elk — to capture the quiet, golden hours of early morning when fog hovered low over the ferns and antlers cut through the mist like silhouettes of another age. He moved slowly, carefully, scanning for movement, the soft crunch of his boots the only sound in the still air.

Then, something caught the light — a glint, sharp and metallic, flashing through the branches ahead. At first, Eric thought it was just litter, maybe a piece of foil or a lost soda can. But when he drew closer, the reflection came again, steady and deliberate, hanging at eye level from a low pine branch.

He stopped. What he saw made him frown.

Keys.

A full key ring, weathered and dull from years of exposure, dangling neatly from a branch — not dropped, not snagged, but deliberately hung there. The ring swayed gently in the wind. Eric hesitated before stepping closer. The metal was tarnished, the leather strap of the keychain cracked and faded. The words Honda Motors were still faintly visible in silver. And attached to the ring, pressed beneath layers of plastic that had yellowed with time, was a photograph.

Four faces smiled up at him. A man and woman, their arms around two little girls who couldn’t have been more than nine and six. It was a classic late-’90s family photo — sunlit, slightly overexposed, the father in a collared shirt, the mother’s hair in soft waves, the girls in matching dresses. Beneath the photo, sealed in the same bag, was a folded note, its paper wrinkled and its ink blurred by moisture but still legible.

Eric’s chest tightened as he carefully pulled it free and read the first line.

If someone finds this, we walked toward the smoke. Thought it was a ranger station or campfire. Got close and realized it was steam from hot springs, not smoke. Not on our map. Van broke down 6 hours behind us. Overheated. Coolant leak. We’re trying to find the highway or a ranger station. It’s been 8 hours walking. Nothing looks right. Hung these keys here in case we pass this tree again. We’ll know we’re going in circles. If you find this, look for green 1998 Dodge Caravan on Forest Service Road 376 near mile marker 12. Family of four. David, Linda, Emma (9), Sophie (6). Please help.

The note was dated August 13, 2001 — 5:30 p.m.

Eric looked down at the date, realizing that whoever had written it had done so twenty-three years earlier. He stared again at the faded photograph, at the smiles of a family who, by now, would have been middle-aged parents and grown daughters — if they had ever made it home. He pulled out his satellite phone, his hands shaking slightly, and called Idaho State Police. Then he waited by the tree for hours, unwilling to leave the keys until rangers arrived.

What Eric had stumbled upon wasn’t just old litter in the woods. It was the first tangible clue in one of Idaho’s most enduring missing-person mysteries — a cold case that had gone unsolved since the summer of 2001.

David and Linda Martinez had been married twelve years when they packed their green Dodge Caravan for what was supposed to be the family vacation of a lifetime. They lived in a modest suburb outside Phoenix, Arizona, a tidy home with a fenced yard and a small above-ground pool that the girls used every summer. David, 38, was a civil engineer — practical, methodical, the kind of man who planned routes down to the mile and double-checked tire pressure before long drives. Linda, 36, was an elementary school teacher known for her patience and her handwritten notes to students. Their daughters, Emma and Sophie, were nine and six — bright, curious girls who shared a bedroom covered in posters of animals and hand-drawn maps of the world.

The plan had been simple. Two weeks on the road, a classic western loop from Phoenix to Yellowstone National Park, with stops in Las Vegas, Salt Lake City, and finally the Wyoming border. Linda had plotted the itinerary herself on an old Rand McNally map, her neat handwriting marking each night’s stop in red ink.

They would leave on August 11, stay overnight in Las Vegas, reach Salt Lake the next day, and then drive into Yellowstone by early afternoon on August 13. They had campground reservations waiting at Madison Campground — site C42, booked months in advance. David had the van serviced the week before: oil change, fluids topped, tires rotated. The mechanic had declared it “ready for anything.”

That morning, Linda’s parents came to see them off. Her mother snapped pictures with a disposable camera — David loading coolers into the back of the van, Linda leaning out the passenger window waving, Emma holding up her stuffed horse, Sophie clutching her purple backpack. The girls were wearing matching shirts that said “Yellowstone Bound.” It was an image of normalcy, of family, of summer — and it would become the last confirmed photo of the four of them alive.

The drive north went perfectly at first. They reached Las Vegas by late afternoon, checked into a Motel 6, and let the girls swim before dinner. Emma wrote postcards to her grandparents. Sophie collected sugar packets from the restaurant, insisting they were “souvenirs.” The next morning, August 12, they continued toward Utah, reaching Tremonton by nightfall.

A clerk at the Quality Inn there remembered them clearly. The girls were “happy and polite,” she said later, still chattering about bears and geysers. David asked her which route was best to reach Yellowstone. She told him to stay on I-15 north to Idaho Falls, then take Highway 20 west — “straight shot, four hours, maybe less.” He thanked her, smiling.

On the morning of August 13, they checked out around 8:15 a.m. The same clerk waved as the family loaded the van. “They were in good spirits,” she recalled. “Like any other family on vacation.”

Traffic records later showed their van traveling north on I-15 through Pocatello, then Blackfoot. Everything seemed ordinary. Then, around 10:30 a.m., they exited the highway near a small sign that read Forest Service Road 376 – Scenic Overlook, 14 Miles.

It was the kind of spur-of-the-moment detour families take on long drives — a quick side trip, maybe for photos or lunch in the woods before continuing on. Linda was known to love scenic views, and the girls probably begged to stop. The weather was perfect, the sky clear and bright. They had time to spare.

The first stretch of road was smooth asphalt, winding gently through the trees. But after three miles, the pavement ended. Gravel took its place. Then dirt. The forest thickened, and the road narrowed into a rugged, rutted track. Still, David pressed on, believing the overlook couldn’t be far.

At around 11:45 a.m., the van began to shudder. The temperature gauge climbed toward red. David pulled over near mile marker 12, lifted the hood, and saw coolant hissing from a cracked hose. The radiator had failed. They were stranded — twelve miles off the main highway, deep in a forest where even radio signals faded.

They had water, snacks, and a small camping stove. But no cell service. No way to call for help. David knew enough about engines to realize they couldn’t risk driving again until the coolant leak was fixed. They waited for another car to pass. None came.

By 1:00 p.m., the August heat was rising, the air shimmering above the asphalt. Linda suggested they start walking. Maybe they could reach the scenic overlook or find a ranger outpost. David hesitated, weighing the risk of leaving the van versus staying put. Finally, they gathered supplies — backpacks with food, water, and the GPS unit — and set off down the road, locking the van behind them.

Sometime later that afternoon, they saw something rising through the trees — what looked like smoke in the distance. Relief must have hit them hard. Smoke meant people, fire, shelter. David probably said, “That’s got to be a ranger station.” They left the road, cutting into the woods toward the source.

But what they found wasn’t a building or a fire. It was steam — plumes rising from hidden geothermal vents, hot springs bubbling between rocks. The forest here was unstable, uneven, the air thick with sulfur. They had wandered far off any marked trail, the GPS useless under the dense canopy.

At some point, realizing how lost they were, David took out a piece of paper — perhaps a page torn from the travel notebook they used to track mileage — and wrote the message that would hang, twenty-three years later, from a pine branch. He listed their names. Their van. The location. And a final plea: Please help.

He hung the keys high, a signal to themselves in case they circled back.

But they never did.

When the Martinez family failed to arrive at Yellowstone that evening, the campground staff assumed they’d been delayed. It wasn’t until the next morning, when Linda’s parents called repeatedly with no answer, that concern set in. By that afternoon, both Arizona and Idaho authorities were alerted.

Two days later, on August 15, a park ranger located the green Dodge Caravan parked on Forest Service Road 376, exactly where David had described in his note. The van was locked. Inside were the family’s clothes, coolers, and a small cooler half-filled with melted ice. The engine compartment showed evidence of overheating — a cracked radiator hose, a streak of dried coolant down the frame.

Search teams spread through the surrounding forest for weeks. Helicopters circled overhead. K-9 units swept the brush. No footprints, no campfire remnants, no clothing — nothing was ever found. By September, the search was scaled back. By winter, it was over.

For more than two decades, the case sat cold, the names David, Linda, Emma, and Sophie Martinez slowly fading from news cycles and memory.

Until June 2024, when Eric Chen spotted something glittering in the Idaho sun — a simple key ring, a faded photograph, and a note dated twenty-three years earlier, still hanging where someone had left it.

And beneath that quiet pine, the forest, as it had for so long, kept the rest of its secrets buried just out of reach.

Continue below

On June 15th, 2024, wildlife photographer Eric Chen was hiking through a remote section of Caribou Tari National Forest in eastern Idaho, 8 miles from the nearest Forest Service road.

He was there to photograph elk, moving slowly through dense timber with his telephoto lens when sunlight reflecting off something metallic caught his eye. He stopped, looked closer. There, hanging from a pine branch at eye level were car keys, not dropped, not lost. Deliberately hung on the branch like someone had placed them there and walked away. Eric approached. The keys were weathered.

The Honda keychain faded from years of sun exposure. But what made him pull out his satellite phone and call authorities was what else hung from that key ring. A laminated family photo. Four faces smiling at the camera. Two parents, two young girls, and attached to the keys sealed in a yellowed plastic bag, a handwritten note. Eric opened the bag carefully. The paper inside was faded.

The blue ink slightly bled from moisture, but the words were still legible. It read, “If someone finds this, we walk toward the smoke. Thought it was a ranger station or campfire. Got close and realized it was steam from hot springs, not smoke. Not on our map. Van broke down 6 hours behind us. Overheated. Coolant leak. We’re trying to find the highway or a ranger station.

It’s been 8 hours walking. Nothing looks right. Hung these keys here in case we pass this tree again. We’ll know we’re going in circles. If you find this, look for green 1998 Dodge Caravan on Forest Service Road 376 near mile marker 12. Family of four. David, Linda, Emma, 9 years old. Sophie, 6 years old. Please help.

The note was dated August 13th, 2001, 5:30 p.m. Eric looked at the date, 23 years ago. He looked at the laminated photo again, the father in a polo shirt, the mother with ’90s style hair, two little girls in matching dresses. Smiling, he called Idaho State Police and stayed at that tree until rangers could reach him. What Eric had found would reopen a cold case that had gone silent in 2001.

A case about a family of four who drove into the Idaho wilderness on a summer vacation and simply vanished. This is their story. David and Linda Martinez had been married for 12 years when they decided to take their daughters on a road trip in the summer of 2001. David was 38, a civil engineer working for a firm in Phoenix, Arizona.

Linda was 36, an elementary school teacher who spent her summers off with their two daughters. Emma was 9 years old, heading into fourth grade, a girl who loved reading and horses, and wanted to be a veterinarian when she grew up. Sophie was six, finishing first grade, obsessed with collecting rocks and announcing that every stone she found was special.

The plan was simple. Two weeks drive from Phoenix to Yellowstone National Park, stopping at national parks and scenic overlooks along the way. They’d done shorter trips before, camping in southern Arizona, weekend drives to the Grand Canyon, but this was their first big family road trip. Linda had planned the route carefully.

Phoenix to Las Vegas for one night, Las Vegas to Salt Lake City, Salt Lake City to Yellowstone with camping reservations already booked at Madison Campground inside the park for August 13th through 15th. After Yellowstone, they’d loop back through Grand Teton, spend a night in Jackson Hole, then head home. David had the van serviced before they left.

Oil change, tire rotation, fluids checked. The 1998 Dodge Caravan wasn’t new, but it was reliable. Green with a dent on the rear bumper from a parking lot accident the year before. License plate Arizona 4. Charlie Mike Tango 739. They left Phoenix on August 11th, 2001. Linda’s parents, Eduardo and Rosa Torres, came over that morning to see them off.

Rosa took photos with her disposable camera. The girls stood in front of the van in their matching purple t-shirts, waving. David loaded the last of the coolers into the back. Linda doublech checked the map one more time. They weren’t a family that used a lot of technology.

David had purchased a Garmin handheld GPS unit the month before. Expensive, but he was an engineer who liked gadgets. Linda preferred paper maps. They had both. David’s cell phone, a Nokia flip phone, was in the center console. Linda didn’t have one. The girls had Gameboys for the drive. That was it. Everything they needed. The drive to Las Vegas was uneventful.

They arrived late afternoon, checked into a Motel 6, swam in the pool. Emma and Sophie were thrilled by the lights on the strip, even though they only drove past on their way to dinner. The next morning, August 12th, they drove north. 8 hours to Tremon, Utah, a small town just off Interstate 15. They checked into a quality in around 700 p.m. The desk clerk who checked them in later told police she remembered them clearly.

The girls were excited, talking about seeing bears at Yellowstone. David asked about the best route north. The clerk suggested staying on I-15 through Idaho Falls, then taking US 20 West into the park. straightforward drive. She said maybe four hours. The Martinez family had dinner at a Denny’s next to the motel.

Sophie collected sugar packets from the table, announcing they were her treasures. Emma read a book about Yellowstone Wildlife while they waited for food. Linda reminded David they needed to check in at Madison Campground by 400 p.m. to hold their reservation. David said they’d leave by 8:00 a.m. Plenty of time.

They went back to the motel, watched TV, slept. August 13th, 2001, the morning that would change everything. They checked out at 8:15 a.m. The same desk clerk saw them loading the van. She waved. They waved back. Got on I-15 northbound. According to toll records and later investigation, they stayed on the interstate until approximately 10:00 a.m. making good time. Idaho Falls was ahead. Yellowstone beyond that.

They would have arrived at the park by 2 p.m. if they’d stayed on that route, but they didn’t. At some point around 10:30 a.m., David saw a sign for Forest Service Road 376. The sign advertised scenic overlook 14 mi. It was the kind of detour families take on road trips, a chance to stretch legs, see something beautiful, take photos.

Linda likely said something like, “We have time.” The girls probably said, “Yes, let’s go.” So, David turned right off the interstate onto FSR 376. It started as a paved two-lane road. Nice. Easy. The forest was beautiful. Tall pines, clear sky, a perfect August day. For the first three miles, the road was smooth. Then the pavement ended.

Gravel began. The road narrowed. David kept driving. The overlook should be ahead. The van handled it fine at first, but the road got rougher. Potholes, ruts from spring runoff. The Garmin GPS showed they were moving away from the highway deeper into the forest, but the scenic overlook sign had said 14 miles. They’d only gone about 10.

David continued. Around 11:45 a.m., the van started making noise, a rattling from the engine. David glanced at the dashboard. The temperature gauge was climbing. He pulled over immediately near mile marker 12, turned off the engine, opened the hood. Coolant was leaking from a cracked hose. The rough road had likely vibrated something loose.

The hose wasn’t completely severed, but enough coolant had leaked that the engine had overheated. They were 12 mi from the interstate on a forest service road that had seen maybe two other vehicles that entire morning. David assessed the situation. They had water bottles, but not engine coolant.

The van wasn’t going anywhere without a repair. His Nokia phone showed no service, no bars. Not surprising. 2001. Cell towers were rare in wilderness areas. Linda checked the paper map. They were somewhere in Caribou Tari National Forest, but the forest service road wasn’t on the map. It was too small, too remote.

David pulled out the Garmin GPS, turned it on, waited for it to acquire satellites. When it did, it showed their position. According to the GPS, they were about 4 miles from Highway 20, the main road to Yellowstone. 4 miles as the crow flies. But between them and that highway was dense forest and steep terrain. Not drivable, maybe walkable. Then David saw something. To the northeast, rising above the tree line in the distance, three columns of what looked like smoke, evenly spaced, rising straight up in the still air. It looked like campfire smoke or smoke signals.

David pointed it out to Linda. She saw it, too. They both thought the same thing. Ranger station or a campground? Someone with a radio? Someone who could call for a tow truck or bring tools. The smo

ke couldn’t be more than a couple miles away, an hour walk, maybe two with the kids. At 12:30 p.m., they made the decision. Lock the van, take the keys, walk to the ranger station or campground, get help, come back with a tow truck. It seemed logical. They weren’t abandoning the van. They were going for help. David packed a backpack with water bottles, granola bars, a first aid kit, and a flashlight.

Linda took a smaller daypack with snacks and Sophie’s asthma inhaler. David grabbed the Garmin GPS. They locked the van, started walking northeast toward the smoke. At first, it felt like an adventure. Emma and Sophie were excited, hiking through the forest, looking for animals.

David led, checking the GPS every 10 minutes to make sure they were heading toward the smoke. Linda brought up the rear, keeping the girls between them. The terrain was harder than it looked. Dense underbrush, fallen logs, small ravines. Progress was slow. After an hour of walking, the smoke didn’t seem any closer. David kept them moving. The GPS said they were heading the right direction. By 300 p.m. they’d been walking for 2 and 1/2 hours.

The smoke was closer, but something seemed wrong. The smell? It didn’t smell like wood smoke. It smelled like sulfur, rotten eggs. David had read about this. Geothermal features, hot springs. The Yellowstone region was volcanic. There were thermal areas throughout eastern Idaho, smaller versions of Yellowstone’s famous geysers.

What they’d seen from the van wasn’t campfire smoke. It was steam rising from hot springs. Not on their map because these were minor thermal features, not major attractions. Just vents in the earth releasing volcanic steam. By 3:30 p.m. they reached the thermal area. Small pools of boiling water, steam vents hissing, mineral deposits staining the rocks orange and white. It was otherworldly and beautiful and completely useless.

There was no ranger station, no campground, no people, just nature. David checked the GPS. They’d walked about 3 mi from the van, but the terrain had forced them to detour around ravines and dense brush. The van was probably four or 5 mi behind them in straight line distance, but six or seven if they retraced their actual path.

Linda said they should go back. David agreed. But here’s where things went wrong. The thermal area was disorienting. Steam obscured landmarks. The sulfur smell was overwhelming. David tried to use the compass feature on the GPS to head southwest back toward the van. But the terrain wouldn’t cooperate. Every direction had obstacles.

Steep drop offs, more thermal pools, dense forest. They had to keep detouring. After an hour of walking, David checked the GPS. They’d barely moved. The constant detouring had them walking in a wide arc instead of a straight line. At 5:00 p.m., they stopped to rest. Emma was tired. Sophie was complaining her feet hurt. Linda checked the water. They’d drunk more than half.

It had been 4 and 1/2 hours since they left the van. David calculated. If they’d been walking all this time and barely made progress, the van was probably 6 to 8 hours away given the terrain. It would be dark in 3 hours. They didn’t have camping gear, just light jackets. August nights in Idaho at 6,000 ft elevation, dropped into the 40s Fahrenheit.

Cold, not deadly, but dangerous without proper gear. David made a decision. He pulled out a small notebook from his backpack, the kind engineers carry for sketching ideas. He tore out a page, found a pen, wrote the note, everything they knew, the van’s location, what had happened, where they were trying to go. He pulled out the car keys, removed his family photo from his wallet.

It was laminated, the kind you get from school photo packages, waterproof. He found a gallon Ziploc bag in Linda’s daypack, meant for trash. He put the note inside, sealed it, attached the bag to the key ring with the photo. Then David looked around, found a prominent pine tree with a low branch at eye level, hung the keys on the branch, stepped back, looked at Linda.

She understood immediately, “If we come back to this tree, we’ll know we’re walking in circles. It was a marker, a test, a survival technique David had read about in hiking guides. If you think you’re lost, leave a marker. If you find your own marker again, you know you’re going in circles. The keys would tell them if they were making progress or just wandering. David told the girls they were leaving the keys as a sign for rescuers, which was partly true.

Emma asked if they were lost. David said no, just turned around. They’d find the van soon. At 5:45 p.m., they started walking again. David picked a direction that seemed most open, avoiding more thermal features. The GPS said southwest. They walked and they never saw that tree again, which means they didn’t circle back, which means they walked in a different direction, away from their own marker, deeper into wilderness. What happened after 5:45 p.m. on August 13th, 2001 is unknown.

The Martinez family was never seen again. No bodies were ever found, but we can reconstruct likely events based on evidence and search records. They continued walking through the evening. As the sun set around 8:30 p.m., visibility dropped. The temperature dropped. They probably tried to find shelter for the night. a depression under a boulder, a cluster of dense trees.

They had light jackets, but not sleeping bags. Sophie had asthma. The cold night air might have triggered an attack. Her inhaler was in Linda’s pack, but inhalers have limited doses. They spent a cold, miserable night in the forest. Possibly no one slept. August 14th, dawn. They would have started walking again. By now, severely dehydrated.

The only water sources were the thermal pools which were undrinkable, scalding hot and full of minerals. They might have found a cold stream, but jardia in untreated water causes illness within days. Disoriented from lack of sleep and water, they continued walking. The terrain in that area is treacherous. Steep ravines hidden by undergrowth, loose rocks, easy to fall.

A broken leg or twisted ankle becomes deadly when you’re already in trouble. Within 48 hours, hypothermia exposure from the second cold night combined with dehydration and exhaustion would have been critical. In wilderness search and rescue, 72 hours is considered the maximum survival time for lost hikers without gear. After that, mortality rates spike.

The Martinez family had water and snacks for maybe 24 hours. After that, nothing. Four people, two of them small children, walking through difficult terrain, getting weaker by the hour. At some point, they couldn’t walk anymore. At some point, they stopped. And over 23 years, in a remote section of forest rarely visited by humans, nature reclaimed them.

Wildlife scattered remains. Weather eroded evidence. The forest kept their secret. August 14th, 2001. While the Martinez family was spending their second day lost in the wilderness, Linda’s sister, Marie, was trying to call them. Linda had promised to call when they arrived at Yellowstone. The camp

ground check-in was 400 p.m. By 6:00 p.m., Marie hadn’t heard from them. She called the Madison campground. They confirmed a Martinez family had a reservation but hadn’t checked in. Marie tried Linda’s parents. They hadn’t heard from them either. Marie tried David’s cell phone straight to voicemail. By 8:00 p.m., Marie called Idaho State Police to report them missing.

Police took it seriously. Family with young children missing in wilderness area. By August 15th, search and rescue operations began. A ranger on routine patrol found the green Dodge Caravan on Forest Service Road 376 at mile marker 12. Doors locked. Luggage inside. Cooler with food. No signs of struggle. The van had clearly overheated.

Coolant leak obvious. But where was the family? Search coordinator established command post at the van. Deployed helicopters with thermal imaging. Search dogs. ground teams, volunteers. The search radius was 5 miles from the van. Standard protocol for lost hikers. Search focused in two primary directions. West toward the interstate 3 mi away.

Logical direction to walk for help and east toward the scenic overlook that had lured them onto this road in the first place. Search dogs were deployed but encountered problems. The thermal area northeast of the van confused them. The sulfur smell interfered with scent tracking. This was documented in search reports. Dogs showed interest heading northeast but lost the scent near the thermal features.

Handlers noted in their reports that volcanic gases were affecting the dog’s ability to track. The search continued anyway. Helicopters flew grid patterns. The dense forest canopy made spotting anything difficult. Thermal imaging from helicopters can detect body heat through light forest cover, but in extremely dense areas with thick canopy, it’s less effective.

Ground teams hiked every trail within 5 mi. Checked ravines, called out names, nothing. August 20th, 6 days missing. Probability of survival dropping. National news picked up the story. Missing family in Idaho wilderness. Photos of David, Linda, Emma, and Sophie appeared on TV. Tips flooded in. Someone thought they saw a green van near Island Park. Search teams investigated.

Wrong van. Someone reported seeing a family matching the description at a rest stop. Wrong family. False leads consumed resources. But the real search area, the correct area, was being covered. Helicopters flew over the tree where the keys hung, possibly passed within a 100 yards.

But hanging keys on a tree branch don’t show up on thermal imaging. Don’t reflect light in a way helicopters can spot through dense canopy. The note that could have redirected the search was there waiting and no one knew. August 28th, 2001, two weeks missing. Idaho State Police held a press conference. The search was being scaled back. Active ground operations would pause.

The case would remain open. But without new leads, without any trace of the family, they had searched everywhere logical. The search had covered over a 100 square miles, focused heavily on the 5m radius from the van. They had not searched 8 mi northeast into rough terrain because there was no reason to believe the family walked that far in that direction. The keys hung on a tree 8.3 mi from the van beyond the search perimeter.

If they’d been 800 yd closer, they might have been found, but they weren’t. In Phoenix, Linda’s parents, Eduardo and Rosa Torres, received the news. Search suspended. Their daughter, son-in-law, and granddaughters were presumed dead, lost somewhere in the Idaho wilderness. Memorial services were planned. At Linda’s elementary school, colleagues created a memory garden.

Emma’s fourth grade class wrote letters to her even though she’d never returned to read them. Sophie’s first grade teacher kept her last art project, a crayon drawing of bears with the words Yellowstone trip in six-year-old handwriting. Linda’s parents couldn’t accept it. Rosa started a website, find the Martinez’s.

com, posted flyers every year at Idaho Trailheads, funded private searches in 2002, 2005, and 2008. Nothing was found. Eduardo died in 2019, heart attack, but family said it was a broken heart. 23 years of not knowing what happened to his daughter and granddaughters. David’s brother Marcus visited the search site every August for 10 years. Stood at the spot where the van had been found.

It had been towed in 2001, sold for salvage. But Marcus knew the exact mile marker. He’d hike into the forest, call their names, leave flowers, then drive back to Phoenix with no answers. Marcus’s own daughter grew up hearing stories about the cousins she’d never met. Emma, who loved horses, Sophie, who collected rocks. They became part of family mythology. The lost ones.

The ones who drove into the forest and never came home. Years passed. 2001 became 2010. 2010 became 2020. The Martinez case remained in the database, unsolved, presumed dead. Occasionally, someone would find the website, Rosa maintained, and send her a message. I’m sorry for your loss. I’ll keep looking.

But no one found anything. The forest kept it secret. The keys hung on that tree through 23 summers, 23 winters. Snow accumulated on them each winter melted each spring. The plastic bag yellowed from UV exposure but held. The laminated photo faded but remained intact. The notes ink bled slightly from moisture but stayed legible. The tree branch held them waiting.

June 15th, 2024. Eric Chen was in that forest to photograph elk. 32 years old, wildlife photographer from Boise, often spent weeks in remote areas waiting for the perfect shot. He had permits to be in that area off trail. He was hiking slowly, scanning for elk when the sun hit the keys just right. Metallic reflection, unusual in a forest.

He walked over, saw the keys, saw the photo, read the note, looked at the date, 23 years. He pulled out his satellite phone, a technology that didn’t exist in 2001, called Forest Service, explained what he found, stayed at the tree until rangers arrived 3 hours later. Idaho State Police assigned Detective Laura Morrison to the case. She’d been in high school in 2001 when the Martinez family vanished.

Now she was the cold case detective pulling the 23-year-old file, reading the search reports, looking at maps. The keys were found 8.3 mi from where the van had been, 8.3 mi northeast beyond the 2001 search radius in terrain so remote it rarely saw hikers. But the note, the note explained everything.

They walked toward the smoke, steam from hot springs, got disoriented in the thermal area, hung the keys as a marker, kept walking, and never circled back. Detective Morrison organized a new search. June 20th through July 10th, 2024. Modern technology, drones with thermal cameras, ground penetrating radar, cadaabver dogs with better training than 2001, LAR mapping to create detailed terrain models.

The search focused on a 2mm radius around the key location, probability maps based on terrain difficulty and human movement patterns. Within a week, they found the thermal area described in the note. Cluster of hot springs and steam vents. Exactly northeast of the van location, exactly where the keys were. The Martinez family had been telling the truth. Every word of that note was accurate. 1.

2 mi from the tree, search teams found a depression under a boulder overhang. Possible shelter site. Fabric scraps consistent with early 2000’s clothing. A partial shoe soul. Small bone fragments in a ravine 8 m from the Keys. scattered over a wide area, consistent with wildlife activity over decades.

Bears, coyotes, scavengers, bodies exposed to elements and animals don’t remain intact. The forest consumes them, returns them to Earth. The bone fragments were collected, sent to forensic labs for DNA analysis, comparison with known samples from the Martinez family, toothbrushes kept by Linda’s parents, hair from Emma and Sophie’s baby books.

As of August 2024, the DNA results are still pending. Forensic analysis takes months, but Detective Morrison believes they found them or what’s left of them. The evidence fits. The location fits. The timeline fits. David Martinez hung those keys on August 13th, 2001 at 5:30 p.m. He was trying to save his family, trying to use logic and engineering thinking to solve a survival problem.

But the forest didn’t care about logic. The forest was vast and indifferent and unforgiving. Four people walked into it unprepared and never walked out. Rosa Torres is 76 years old now. She lives in Phoenix, still maintains the website. When Detective Morrison called her in June to tell her about the keys, Rosa broke down. 23 years. 23 years of not knowing.

The DNA results aren’t confirmed yet. But Rosa knows. She knows her daughter and granddaughters are gone. The keys gave her something she’d been missing, not closure. You can’t have closure when your daughter and grandchildren die lost and afraid in the wilderness. But she has an answer. She knows what happened.

She knows they tried to survive. She knows David hung those keys trying to protect them. She knows they didn’t suffer long. Hypothermia causes confusion and eventual unconsciousness. It’s not peaceful, but it’s not prolonged agony. They were together. That’s what Rosa tells herself. In those final hours, they were together.

The keys are in an evidence locker now, but Eric Chen took photos before rangers arrived. The image shows exactly what he saw. A branch, keys hanging, a family photo, faded but recognizable. David in a polo shirt, Linda with ’90s hair, Emma and Sophie in matching dresses, smiling. It’s a photo from happier times, maybe from 1999 or 2000.

Before they ever planned that Yellowstone trip, before they ever saw the sign for Forest Service Road 376, before everything went wrong, they look happy in that photo. A normal family, they could be anyone. They could be your family. That’s what makes this story haunting. It’s not complicated. It’s not sinister. It’s just a series of small decisions that compounded into tragedy.

Take the scenic detour. Walk toward the smoke, hang the keys, and keep walking. Each decision made sense at the time. Each decision was logical, and each decision led them deeper into a situation they couldn’t escape. The tree where the keys hung is marked now. GPS coordinates logged. A small memorial plaque is planned. Not for tourists.

This area is too remote for casual visitors. But for the search and rescue community, for the people who understand how quickly things can go wrong in the wilderness, how a family vacation can become a disaster in a single afternoon. How 23 years can pass before anyone finds the evidence that explains what happened.

That tree stands as a reminder. The wilderness doesn’t care about your plans. It doesn’t care about your GPS or your cell phone or your good intentions. It’s beautiful and deadly and it keeps secrets. For 23 years, it kept the Martinez family secret. Only the keys knew the truth, and they hung there, waiting until someone finally found

News

Three College Friends Vanished Hiking in 2014 — 9 Years Later, Hikers Found Their Shelter…

Three College Friends Vanished Hiking in 2014 — 9 Years Later, Hikers Found Their Shelter… In June 2014, three…

She Sent a Final Text From Her Tent — Ten Years Later, Her Backpack Was Found in a Cave…

She Sent a Final Text From Her Tent — Ten Years Later, Her Backpack Was Found in a Cave… …

Nurse Vanished on a Hike in 2023 — Weeks Later, Her Apple Watch Was Found…

Nurse Vanished on a Hike in 2023 — Weeks Later, Her Apple Watch Was Found… In late June…

My Family Cashed My Disability Payments For A Decade—Until Grandpa Asked One Real Question…

My Family Cashed My Disability Payments For A Decade—Until Grandpa Asked One Real Question… The sound of silverware clinking…

My Parents Gave My Brother a $950K Home. Then, They Came to Take Over My House. But When I Refused…

My Parents Gave My Brother a $950K Home. Then, They Came to Take Over My House. But When I Refused……

My Sister Hired Private Investigators to Prove I Was Lying—and Accidentally Exposed Her Own Fraud

My Sister Hired Private Investigators to Prove I Was Lying—and Accidentally Exposed Her Own Fraud I step out of…

End of content

No more pages to load