Why Patton Wanted to Attack the Soviets in 1945 – The Warning Eisenhower Refused to Hear

On the gray, damp afternoon of May 7, 1945, in a commandeered German mansion outside Frankfurt, the sounds of victory filled the air. Outside the gates, American soldiers were celebrating with reckless joy—bottles of captured brandy cracked open, songs echoing down the ruined streets, bursts of rifle fire marking the end of six years of carnage. Germany had surrendered. The war in Europe was over. The nightmare that had consumed the world had finally burned itself out.

Inside the mansion, the mood was nothing like the chaos outside. The noise was distant here, muffled by marble walls and thick velvet curtains. In a quiet room that still smelled faintly of old cigars and ink, two men sat across from each other at a long, ornate table. Both had carried the weight of the free world on their shoulders. Both had seen death in quantities too vast to measure. And yet, at that moment of triumph, one of them could not celebrate.

General George S. Patton sat rigidly in his chair, his gloved hands resting on the table’s polished surface. Across from him, Supreme Commander Dwight D. Eisenhower leaned back slightly, his face calm but tired, the lines of exhaustion etched deep beneath his eyes. Between them, on the table, lay a single folder—unmarked, but heavy with meaning.

Patton’s gaze was fixed on Eisenhower, and when he spoke, his voice was steady, quiet, and grim. “We’re going to have to fight them eventually,” he said. “Let’s do it now, while our army is intact—and we can win.”

For a long moment, Eisenhower said nothing. The words hung in the air like gun smoke. Outside, someone laughed, a shout of victory muffled by stone. Inside, the silence was suffocating.

He knew exactly whom Patton meant.

Patton wasn’t talking about the Germans. The Reich was gone, its cities reduced to ash, its soldiers disarmed and starving in prison camps. He wasn’t talking about Japan either. He meant the Soviet Union—America’s wartime ally, the nation whose red flags now fluttered above the smoldering ruins of Berlin.

Eisenhower exhaled slowly, his fingers brushing the edge of the folder. For three years, he had worked tirelessly to hold the alliance together—balancing Roosevelt’s diplomacy, Churchill’s stubborn pride, and Stalin’s brutal paranoia. Against all odds, it had worked. Together they had crushed Hitler’s empire. But Patton’s words threatened to unravel that fragile peace before it had even begun.

“George,” Eisenhower said at last, “you don’t understand politics.”

Patton didn’t blink. “I understand war,” he said. “And I understand men like Stalin.”

“The war is over,” Eisenhower replied, his tone firm. “We’re going home.”

To anyone else, it might have sounded final. But Patton heard something else beneath the words—hesitation. A quiet acknowledgment that Eisenhower understood the truth but had already decided to ignore it.

Patton’s jaw tightened. He wasn’t speaking out of restlessness or bloodlust. He had no illusions about the cost of war. He had walked through the wreckage of too many cities, buried too many of his men. But he also knew that history had a cruel habit of rewarding hesitation.

The silence between the two generals stretched on, heavy and unyielding. Somewhere outside, a radio was playing—an American broadcast announcing the end of hostilities in Europe. Eisenhower’s staff was already preparing for the next phase: occupation, reconstruction, withdrawal. But Patton’s mind was still on the eastern horizon.

In the weeks leading up to that meeting, his Third Army had driven deeper into Central Europe than any other Allied force. His tanks had crossed Germany into Czechoslovakia, rolling past villages half-destroyed by retreating German troops. They had reached the undefined line where the Western Allies met the Red Army—a line marked not by fences or flags, but by tension and mistrust.

What Patton saw there unsettled him more than any German offensive ever had.

The Soviet soldiers he encountered weren’t acting like temporary allies. They weren’t behaving like guests on foreign soil. They were taking everything they could carry—food, machinery, livestock, factory parts. Entire trainloads of equipment rumbled eastward, bound for Moscow and the industrial heartland of the Soviet Union.

Wherever the Red Army went, the same pattern followed. Towns stripped bare. Machinery dismantled and hauled away. Women assaulted. Men dragged from their homes and lined up against walls. Hume-faced Soviet officers barking orders through interpreters while their men emptied cellars and loaded wagons.

Patton had seen plenty of brutality in war. He had fought across North Africa, Sicily, France, and Germany. He had seen men die by the thousands. But what he saw in Eastern Europe was different. This wasn’t war—it was conquest.

He wrote to his wife, Beatrice, that April, his tone colder than she had ever read from him before. “I have no desire to understand the Russians in a sentimental way,” he said. “Only to calculate how much steel it will take to kill them, if it comes to that.”

The words shocked even her, but Patton’s staff officers had heard the same sentiment spoken more bluntly. He had seen the future, and it wore a Red Star.

Reports from his intelligence units only deepened his concern. Soviet NKVD officers were setting up command posts in Poland and Czechoslovakia. Resistance fighters who had spent years battling Nazi occupation were now being arrested by Soviet agents, accused of “anti-Communist agitation.” Entire factories were being dismantled and shipped east. Engineers, mechanics, and laborers were “invited” to relocate to work in the Soviet Union—most never returned.

The pattern was unmistakable. Wherever Soviet forces arrived, free governments vanished.

And then came the reports that turned Patton’s unease into fury. American prisoners of war—men liberated from German camps by advancing Soviet units—had been detained, stripped of their gear, and sometimes beaten or executed. Their watches, boots, and rations stolen by soldiers who were supposed to be their allies. Some POWs swore that German captivity had been more bearable.

By the time Germany surrendered, Patton’s doubts had crystallized into conviction. The alliance with the Soviet Union was a temporary convenience, not a friendship. Stalin’s armies weren’t pausing—they were advancing, quietly redrawing Europe’s borders with rifles and tanks.

So when Patton sat across from Eisenhower that day, it wasn’t to provoke. It was to warn.

He came armed not with emotion, but with data—intelligence reports, troop assessments, logistical studies. He had done the math. The Soviet Union was vast, yes, but bleeding. Twenty-seven million of its people were dead. Its railways shattered, its factories relocated or destroyed. The Red Army was huge but exhausted, stretched thin across hundreds of miles of occupied territory, feeding itself on what it could plunder.

By contrast, the American forces were at their absolute peak. Fully supplied, well-rested, and bolstered by the greatest industrial engine in the world. The U.S. held air supremacy over all of Europe. Its bombers could strike anywhere from the Baltic to the Black Sea. The Soviets, by comparison, had almost no strategic air power left.

To Patton, the equation was simple. The United States could win. Quickly.

In one of his briefings that spring, he told Under Secretary of War Robert Patterson, “We could beat the Russians in six weeks.”

It wasn’t bravado. It was an assessment—cold, mathematical, terrifyingly confident.

He argued that Soviet morale would collapse if the Americans advanced. The Red Army, he believed, was held together by fear, not loyalty. Its soldiers had fought fiercely to defend their homeland, but now they were far from it—occupying countries that despised them. If pushed hard enough, they would surrender or melt away.

And then came the most controversial part of his plan.

“We can arm the Germans,” Patton said.

There were hundreds of thousands of Wehrmacht soldiers sitting in Allied prison camps. Men who had fought bitterly against the Soviets, who feared and hated them more than anyone else. Patton believed they could be re-equipped, re-officered, and used to hold the front while the Americans advanced.

“I’d rather have a German division on my side than a Russian one,” he wrote later.

To the political leadership in Washington, the idea was unthinkable. The United States had just sacrificed hundreds of thousands of lives to defeat Nazi Germany. To rearm those same soldiers—even under Allied command—felt like a betrayal of every promise made to the world. But Patton didn’t see it through the lens of morality. He saw it through the lens of survival.

He wasn’t talking about vengeance or ideology. He was talking about inevitability.

Patton believed that the war had not ended, only paused. That the enemy’s flag had changed color, but not its ambitions. And as Eisenhower rose from the table that day, offering a polite but final dismissal, Patton sat perfectly still, his gloved hands folded over his cap, staring at the floor.

The victory celebrations thundered outside. But in that quiet, sunlit room, Patton felt none of it.

Because for him, the next war had already begun.

On the afternoon of May 7th, 1945, in a commandeered German mansion outside Frankfurt, two men who had just helped save the world sat facing each other across an ornate table. Outside, American soldiers were cheering, drinking, firing rifles into the air in wild celebration. Germany had finally surrendered. The war in Europe, the nightmare that had consumed the continent, was officially over.

Inside that quiet room, George S. Patton was not celebrating. He studied the face of the man across from him, Supreme Commander Dwight D. Eisenhower, the admired architect of victory in Europe. Patton had not come to bask in triumph. He had come to deliver a warning that he knew Eisenhower did not want to hear.

Words that would strain their friendship, end his own career, and later be described by politicians and newspapers as madness. We are going to have to fight them eventually, Patton said, his voice steady. Let us do it now while our army is intact and we can win. He was not talking about the Germans. Their Reich lay in ruins.

He was talking about the Soviet Union. For a moment, Eisenhower simply looked at him. For 3 years, he had painstakingly held together an alliance with Joseph Stalin’s regime, balancing egos, ideologies, and military needs to defeat Adolf Hitler. In American newspapers, Stalin was Uncle Joe, the gruff but lovable partner in victory.

News reels praised the Red Army as heroic liberators. School children collected scrap metal and cheered for their Soviet allies. And here was Patton, the most aggressive of America’s generals, calmly suggesting that the United States should turn its guns on that ally immediately before the dust of victory had even settled.

George, you do not understand politics. Eisenhower finally replied, “The war is over. We are going home.” In that instant, Patton saw something that chilled him more than any battlefield. Eisenhower understood exactly what he was saying. On some level, Ike knew that Patton’s assessment of the Soviet threat had merit, but he also knew he would not act on it. The political costs were too great.

What followed was one of the most fateful silences in American military history. A window of opportunity, if it existed at all, closed quietly without a shot being fired. Patton had reached his conclusion, not from abstract theory, but from what his third army had seen firsthand as it plunged deeper into central Europe than any other Allied force.

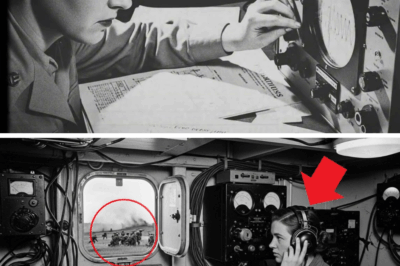

His tanks had rolled across Germany into Czechoslovakia and up against the vague and shifting line separating the Western Allies from Soviet territory. Wherever he went, he encountered something that disturbed him far more than the broken remnants of the Vermacht. He saw the Red Army. Patton’s officers and intelligence teams reported scenes that shocked even men hardened by years of combat.

Soviet troops were not behaving like temporary liberators. They were acting like conquerors who meant to stay. Reports filtered in of systematic looting, towns stripped of machinery and livestock, trains loaded with stolen equipment heading east. There were accounts of mass rapes, brutal reprisals, and summary executions of civilians suspected of anti-communist sympathies.

Entire communities were being uprooted and shipped towards Soviet labor camps. Patton did not romanticize war. He was no stranger to cruelty. But what he was seeing in Eastern Europe convinced him that the Soviet Union was not a partner in a new democratic order. It was a totalitarian empire pushing its frontier west.

In April of 1945, he wrote to his wife Beatatrice with characteristic bluntness. He confessed that he had no desire to understand the Russians in any sentimental way, only to calculate how much steel it would take to kill them if it came to that. They gave him, he wrote, the impression of a force that must be feared in any future rearrangement of world power.

While American diplomats in Washington still hoped that Stalin would respect promises of free elections and national self-determination, Patton was watching those promises dissolve on the ground. He met American prisoners of war who had fallen into Soviet hands near the end of the conflict.

Their stories disturbed him more than German captivity ever had. They spoke of having their watches, boots, and rations stolen. Officers who protested were beaten or shot. They described conditions so bad that some said they preferred their former German capttors to their new Soviet allies. The pattern continued. Soviet units dismantled German factories piece by piece, loading entire industrial plants onto rail cars to be shipped east.

In Poland, Romania, Hungary, and Bulgaria, Sovietbacked communists were moving into ministries, police stations, and courts. Resistance fighters who had risked their lives against Nazi rule were now being arrested, interrogated, and in many cases executed, not by the Gustapo, but by Soviet security forces.

By the time Germany surrendered, Patton’s concerns had hardened into a cold, detailed assessment. What he proposed to Eisenhower and later to senior officials in Washington was not the outburst of a frustrated warrior unwilling to accept peace. It was a strategic plan built on intelligence reports, battlefield experience, and a harsh reading of Soviet capabilities and weaknesses. His logic was brutal and simple.

The Soviet Union had paid a staggering price to defeat Germany. Roughly 27 million of its people were dead. The Red Army, though massive, had been bled white. Its forces in Eastern Europe were extended far from their supply bases, living off captured depots, requisitioned food, and whatever they could strip from conquered lands.

Their logistics lines stretched back thousands of miles to a country devastated by war. American forces, by contrast, stood at the peak of their power. They enjoyed overwhelming air superiority. Their supply lines ran back across France to ports in the Atlantic, supported by an industrial machine untouched by enemy bombs. American divisions were fully equipped, wellfed, and backed by fleets of bombers that could, in Patton’s judgment, wreck Soviet transport and communication hubs at will. To Under Secretary of War Robert Patterson, Patton summarized his

estimate in stark terms in that same month of May 1945. We could beat the Russians in 6 weeks. The Soviet Union, he argued, had no real strategic bombing capability. Its anti-aircraft defenses were limited. American air power alone could shred Soviet logistics. On the ground, Soviet tank production was impressive in quantity, but after years of continuous fighting, their armored units were worn down and mechanically unreliable.

American M4 Sherman tanks might not be as heavily armored as some German or Soviet models, but they were dependable, and there were vast numbers of them ready for combat. Most striking to Patton was the human factor. Soviet soldiers had fought with ferocity to defend their homeland, but now they were being asked to occupy countries that were not theirs, policing populations that did not welcome them.

Many of these troops, he believed, had little enthusiasm for permanent garrisons in foreign lands. If an American offensive drove east, Patton predicted that morale in the Red Army would crack. He was convinced that many Soviet soldiers would surrender, desert, or simply refuse to fight. Then there was the most controversial part of his plan. We can arm the Germans, Patton proposed.

Across Europe, hundreds of thousands of former Vermached soldiers sat in prisoner of war camps, staring at uncertain futures. Many loathed and feared the Russians far more than they hated the Americans or British. In Patton’s view, those men could be re-equipped, reofficered, and turned against the Soviets.

“I would rather have a German division on my side than a Soviet one,” he wrote. To the political leaders in Washington, this suggestion was horrifying. The United States had just sacrificed immense treasure and blood to defeat Nazi Germany. To arm German troops again, even under Allied command, felt like a betrayal of everything the war had been fought for. Yet Patton’s reasoning followed a ruthless logic.

If the Soviets were the next threat, why not use the enemies of that enemy, however recently defeated, to blunt their advance? Within weeks, some of Patton’s remarks were leaked to the press. The picture painted was not one of a coldeyed strategist making a grim calculation, but of a reckless militarist who had gone too far, someone sympathetic to Germans and obsessed with starting another war.

Eisenhower had reasons to reject Patton’s scheme that went beyond fear of headlines. The American public wanted desperately to bring their sons home. Congress was already demanding rapid demobilization and warning against new entanglements in Europe. Logistically, American forces had been positioned to occupy Germany, not to push deeper into Poland and beyond. Supply lines would have to be reorganized at enormous cost.

But beneath these practical obstacles lay a more decisive barrier, politics. Harry Truman had only recently assumed the presidency after Franklin Roosevelt’s death. He was still settling into the role, still surrounded by many of Roosevelt’s advisers, and still committed outwardly to a policy of cooperation with Stalin.

At Yalta, the Allies had agreed on a framework for postwar Europe that formalized spheres of influence and promised free elections in liberated countries. To propose attacking the Soviet Union in that context would have been seen as tearing up solemn commitments. Eisenhower understood this.

If he presented a plan like Patton’s to the president, he would be branded a wararmonger. A man who wanted to ignite a new world war just as the previous one ended. The press would attack him relentlessly. Congress would turn on him. His reputation as the calm, steady architect of victory would be shattered. He also believed genuinely that diplomacy offered a path forward.

Like many leaders of the time, Eisenhower hoped that once the emergency of war passed, the Soviet Union would moderate, that tensions would ease, and that the newly formed United Nations could serve as a forum to manage disputes. He thought in terms of institutions, treaties, and political processes.

Patton thought in terms of opportunity and force. George sees the world as a battlefield. Eisenhower told his chief of staff, “He does not understand that we have to live with these people.” In this disagreement, Patton was not entirely alone. Across the English Channel, Winston Churchill was arriving at similar conclusions.

Churchill had distrusted boleeism from the moment of the Russian Revolution in 1917. He had only joined forces with the Soviets out of necessity to defeat the greater immediate evil of Hitler. Even as the war wound down, he warned that Soviet aims did not stop with driving out the Nazis. By April of 1945, Churchill was sending increasingly urgent messages to Truman and Eisenhower.

He urged them to push Western forces as far east as possible before the Red Army cemented its control. He wanted American and British troops, not Soviet ones, entering cities like Berlin, Prague, and Vienna. On May 12th, 1945, Churchill used a phrase that would soon become famous. An iron curtain, he wrote to Truman, has been drawn down upon their front.

Behind that curtain, he warned, no one truly knew what was happening, but he suspected that freedom was being strangled. That same month, Churchill asked his military planners to draft a bold and unsettling concept, Operation Unthinkable. It was in essence an allied offensive aimed at pushing Soviet forces out of Poland and Eastern Europe using rearmed German units alongside British and American divisions.

The British chiefs of staff studied the idea. Their conclusion was sobering but not dismissive. Under the right conditions and if launched immediately, they believed such an operation was militarily possible. It would be costly and require full commitment, but it might succeed in driving the Red Army back.

Churchill forwarded the plan to Truman. The American president barely hesitated before rejecting it. The thought of attacking the Soviet Union, especially with German soldiers fighting under Allied command, revolted him. The political and moral implications were too enormous to contemplate. When Patton learned that Churchill had entertained essentially the same strategy he himself had advocated, he felt a bitter sense of vindication. At least one man in power understands what we are facing, he told his staff.

Within months, Churchill’s fears began to be confirmed. Soviet control over Eastern Europe hardened. Promised elections were delayed, manipulated, or cancelled altogether. Opposition leaders vanished into prisons or graves. Communist parties backed by Soviet security organs took command of police forces, bureaucracies, and the press.

Back in the United States, the way the media talked about Patton shifted dramatically. During the war, he had been portrayed as a colorful, if controversial, hero, the flamboyant tank commander whose profanity laced speeches inspired troops and terrified Germans. In May and June of 1945, however, the tone changed.

Journalists seized on his harsh comments about the Soviets and his suggestion of rearming German units. Columnist Drew Pearson described Patton’s statements as deeply troubling, suggesting that the general’s judgment might be slipping. At a moment when the country was longing for peace, Pearson insisted Patton seemed intent on courting another catastrophic conflict.

Editorials in respected newspapers argued that his remarks showed a dangerous ignorance of diplomatic reality. Magazines wondered aloud whether this brilliant battlefield commander was simply incapable of adapting to peace time. None of these outlets seriously investigated the reports his intelligence teams were sending back from Eastern Europe. They did not delve into Soviet atrocities or the systematic installation of puppet governments. The narrative hardened.

Patton was a superb warrior, but also an unstable relic of war unsuited to the new era. Pressure on Eisenhower increased. By August of 1945, officials in Washington were making it clear that Patton’s public criticisms were unacceptable. The trigger came from an entirely different policy debate, denazification.

At a press conference, Patton was asked about efforts to purge all former Nazi party members from positions in the German administration. He responded with characteristic bluntness. Many of these people, he argued, had joined the party for practical reasons, not out of ideological fervor. To remove them all from office was, in his words, idiotic.

He compared the situation to an American political contest, saying that belonging to the Nazi party in Germany was often no more serious than being a Democrat or a Republican at home. The remark was explosive. Reported without nuance, it made it sound as if Patton was equating participation in a murderous totalitarian movement with membership in a Democratic party. Headlines accused him of trivializing Nazi crimes.

Politicians denounced him. The controversy gave Eisenhower the excuse he needed. On September 28th, 1945, Eisenhower relieved Patton of command of the Third Army. Officially, the reason was his inappropriate comments about denazification. Unofficially, everyone in Patton’s circle understood that his relentless warnings about the Soviets had played an equally large role.

Stripped of operational command, Patton spent his final months in Europe doing what he could, observing, writing, and warning. His letters from October and November 1945 read like a mixture of military analysis and prophecy. He urged American leaders to maintain a posture of strength, to keep their boots polished and bayonets sharpened, and to show the Red Army an unmistakable image of power.

This, he insisted, was the only language Moscow truly respected. If the United States disarmed and relaxed, he warned, victory over Germany would be hollow. they might have defeated one enemy only to hand the field to another. In early December of that year, Patton met again with Under Secretary Patterson. He laid out his bleak forecast.

The Soviets, he said, would not withdraw from Eastern Europe. They would transform temporary occupation into permanent control. They would spread communism through Western Europe by subversion, intimidation, and when necessary, force. Eventually, the United States would be drawn into military confrontation with them. We are going to fight them eventually, he repeated.

In 5 years or 10 years or 20 years, we will wish we had done it in 1945 when we had the chance. Patterson listened politely. Then he gave the same answer Eisenhower had in a more bureaucratic form. Washington had no appetite for confrontation. The American public wanted peace, not another crusade.

Whatever Patton saw on the ground, his proposed response was politically impossible. 3 days later, on December 9th, 1945, Patton’s staff car was involved in a collision near Mannheim. A truck suddenly turned in front of his vehicle. The general was thrown forward, suffering a severe neck injury that left him paralyzed from the shoulders down.

Other passengers in the car escaped with minor wounds. Patton, the man who had survived countless dangers at the front, was mortally injured in what appeared to be a mundane traffic accident. He lingered in a hospital bed for nearly 2 weeks, unable to move. On December 21st, 1945, George S. Patton died at the age of 60. The timing of the accident and the strange circumstances surrounding it fueled rumor and speculation almost immediately. Some pointed to the driver’s odd explanations.

Others noted the coincidence that the one general most outspoken about the Soviet threat had been silenced days after making a final dire prediction to Washington. But no credible evidence of assassination has ever surfaced. The more sober conclusion is that it was a tragic accident, one that nevertheless removed from the stage the loudest voice demanding a showdown with Moscow when it was weakest.

In the years that followed, events unfolded in a pattern that eerily echoed Patton’s warnings. By 1946, Soviet power in Eastern Europe was entrenched. Poland, East Germany, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Romania, and Bulgaria all fell under communist control. The free elections promised at Yaltta proved to be a mirage. In Poland, resistance leaders who had fought the Nazis for six years were arrested, tried on fabricated charges, and either executed or sent to labor camps deep inside the Soviet Union. In Czechoslovakia, a communist coup in 1948

overthrew the democratic government. That same year, Foreign Minister Yan Maserik died in a mysterious fall from a window. Officially ruled a suicide, but widely suspected to be murder. The pattern repeated from country to country. A Soviet presence was followed by the installation of communist governments, the suppression of opposition parties, the nationalization of property, and the creation of secret police forces loyal to Moscow.

Between 1945 and 1989, communist regimes in Eastern Europe and the wider Soviet block killed roughly 1 million people. Millions more were imprisoned, tortured, or subjected to everyday repression. The iron curtain that Churchill had envisioned became a literal border of barbed wire, concrete walls, and watchtowers.

The Cold War that Patton had wanted to preempt lasted for roughly 45 years. It cost trillions of dollars in arms spending and claimed millions of lives in proxy conflicts from Korea to Vietnam, Afghanistan to Angola. By 1949, the Soviet Union had detonated its own atomic bomb, ending America’s nuclear monopoly and ushering in an age of mutual annihilation.

By 1950, confronted with North Korean aggression backed by Moscow and Beijing, the United States found itself in the very sort of military clash with communist forces that Patton had predicted, except now under far more dangerous conditions. Patton’s argument had never been that war with the Soviets could be avoided altogether.

His claim was that the moment of surrender in 1945 was the least dangerous time to confront them militarily. The Red Army was exhausted. Soviet industry was shattered. American power was at its peak. If the showdown was inevitable, he believed better to face it then than to wait for the Soviets to regroup, rearm, and acquire nuclear weapons.

Whether his military assessment was entirely correct remains a matter of debate among historians and strategists. What is far less debatable is that the broad outline of his warnings was borne out by subsequent events. Soviet occupation of Eastern Europe did become effectively permanent until the late 1980s. Communist expansion did spread globally.

Military confrontation with communist forces did occur repeatedly at high cost. By 1947, even many liberals who had supported Roosevelt’s more hopeful approach to Moscow had to admit that something fundamental had gone wrong. George Kennan’s famous long telegram from Moscow described the Soviet regime as inherently expansionist and ideologically committed to undermining the West.

Language that in a more measured tone closely mirrored Patton’s visceral warnings from 1945. The Truman Doctrine announced that same year committed the United States to a policy of containing Soviet influence wherever it began to spread. Yet containment came with its own tragic tradeoffs. It accepted Soviet control over Eastern Europe as a grim fate accomply drawing the line further west.

It meant fighting limited wars in Asia instead of risking a general conflict in Europe. It meant living for decades under the shadow of nuclear annihilation. Conservative critics would later seize on Patton as a prophetic figure, a man who had seen what others refused to see. General Douglas MacArthur, who would clash with Truman over strategy in the Korean War, wrote that Patton understood the nature of communism and knew that it had to be confronted militarily.

His removal, MacArthur argued, was a tragedy with long-term consequences. Decades later, Ronald Reagan invoked Patton’s warnings as he argued that the United States must adopt a stance of strength and moral clarity toward what he called the evil empire. When the Berlin Wall crumbled in 1989, and when the Soviet Union dissolved in 1991, some conservatives pointed back to Patton’s May 1945 conversation with Eisenhower.

Reagan’s policy of military buildup and confrontation, they argued, validated Patton’s instincts. If the Soviet system could ultimately be broken by pressure, then perhaps in some alternate history where Patton’s advice had been heeded, Eastern Europe might have been freed 45 years earlier. But the question of whether Patton’s proposed offensive would have succeeded is ultimately unanswerable.

The political reality of 1945 made his plan almost unimaginable for democratic leaders. No matter what its military chances, the United States and Britain were weary, their people desperate for peace. They had just emerged from a cataclysm whose horrors were still being uncovered in the death camps.

To ask those societies to launch another war immediately, this time against a recent ally, was asking for something they were almost certainly incapable of providing. Patton’s tragedy then was not simply that he was right. It was that he may have been right at a moment when his country could not act on that truth.

His story poses questions that have not gone away. When should the United States confront an emerging threat militarily rather than relying on diplomacy and hope? How far should generals go in advocating for strategies that are militarily sound but politically impossible? When do political leaders have a duty to ignore public opinion and act preemptively? And when does such action become recklessness? Similar debates echoed after the attacks of September 11th when policymakers argued over whether to use preemptive force against terrorist networks and

their state sponsors. They echo again as America grapples with the rise of China and the expansion of its influence. Do you confront a rival power early while the balance of strength favors you? or do you wait? Hope that engagement and negotiation will moderate their ambitions.

Patton represents one pole of that argument, the warrior who believes threats should be crushed while they are still vulnerable. Eisenhower in 1945 represented the other, the coalition builder who believes in diplomacy, institutions, and the slow grinding of politics. In that sense, Eisenhower’s handling of patent can be read in two very different ways.

On one interpretation, the system worked as designed. A general who refused to accept civilian guidance was relieved. Military power remained subordinate to elected authority. On another interpretation, the system failed. A general who had correctly identified a looming strategic danger was sidelined because his warnings were inconvenient and uncomfortable.

Eisenhower himself would later acknowledge that he and others underestimated the nature of the Soviet threat in those early postwar years, but he never conceded that Patton’s suggestion of immediate military action against Moscow had been either wise or feasible. From his perspective, the politics, the morale of his troops, and the balance of obligations all made such a move irresponsible.

Patton did not care about political feasibility. He cared about defeating what he saw as America’s next enemy before that enemy grew stronger. That was the lens through which he viewed history, war, and his own duty. He died on December 21st, 1945 in a hospital bed in Germany, paralyzed, far from the front lines he loved.

At his request, he was buried not in a grand national cemetery in the United States, but among the soldiers of the Third Army in Luxembourg, the men with whom he had fought and bled. In death, Patton became larger than life, a symbol onto which different groups projected their own beliefs. To many conservatives, he embodied the clarity and courage to name evil and advocate force when necessary.

To many liberals, he symbolized the dark side of militarism, the man who too easily reached for war as a solution. To most of the public, he remained the fiery tank commander who had helped break Hitler’s grip on Europe. The question of whether he was right about the Soviet Union was answered not by arguments but by events, permanent Soviet domination of Eastern Europe for decades, global communist expansion, and a cold war that reshaped world politics until the end of the 20th century.

Whether his chosen remedy would have prevented that history or plunged the world into something worse, we will never know. What we do know is that George S. Patton saw in the spring of 1945 a danger that others preferred not to face. He spoke about it bluntly, refused to be quiet, and paid for that refusal with his career and possibly with his life.

The leaders who dismissed his warnings spent the next 45 years struggling to manage the consequences of the reality he had tried to confront. His voice still echoes, a reminder that there are moments when the person who sees most clearly is also the one most easily labeled dangerous, unhinged or extreme.

Sometimes the prophet is pushed aside, the truth teller is silenced, and the warrior who insists on naming the next enemy is removed by politicians who would rather enjoy victory than face the next storm gathering beyond the horizon. Mason.

News

CH2 They Mocked His ‘Enemy’ Rifle — Until He Killed 33 Nazi Snipers in 7 Days

They Mocked His ‘Enemy’ Rifle — Until He Killed 33 N@zi Snipers in 7 Days At 6:42 a.m. on…

CH2 How Did Hitler Fund a Huge Military When Germany Was Broke?

How Did Hitler Fund a Huge Military When Germany Was Broke? Germany, 1923. The winter air was sharp and cold,…

CH2 How One Woman Used a 0.16-Second Echo to Collapse a 4,200-Man Japanese Tunnel Fortress

How One Woman Used a 0.16-Second Echo to Collapse a 4,200-Man Japanese Tunnel Fortress At 6:42 a.m. on June 26,…

He Mocked Me for Approaching the VIP Lift—Then It Revealed My Classified Identity…

He Mocked Me for Approaching the VIP Lift—Then It Revealed My Classified Identity… The air in the lower levels of the…

He Mocked Me on Our Date for Being a Civilian—Then Found Out I Outranked Him

He Mocked Me on Our Date for Being a Civilian—Then Found Out I Outranked Him The pressure on my…

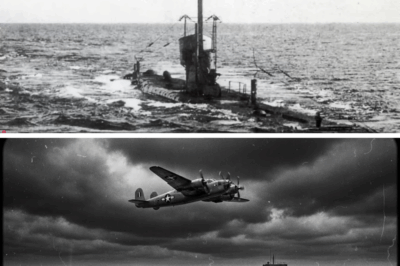

CH2 German Submariners Encountered Sonobuoys — Then Realized Americans Could Hear U-Boats 20 Miles Away

German Submariners Encountered Sonobuoys — Then Realized Americans Could Hear U-Boats 20 Miles Away June 23rd, 1944. The North…

End of content

No more pages to load