Why German Infantry Feared the 101st Airborne More Than Any Other Division

June 6th, 1944. 02:15 hours. Sainte-Mère-Église, Normandy. The night was alive with sound—wind roaring through the hedgerows, the metallic clatter of weapons, the distant rumble of anti-aircraft guns. Lieutenant Hermann Friedrich von der Heyde pressed himself against the cold stone wall of a farmhouse, staring upward in disbelief. The black sky was filled with pale silk ghosts—parachutes drifting through the mist, hundreds upon hundreds of them, blotting out the stars. For a moment, the veteran officer thought he was dreaming. The sky itself seemed to be falling.

The first American paratroopers were already on the ground, scattered across his regiment’s defensive perimeter. Von der Heyde’s Sixth Parachute Regiment, veterans of Crete and the Eastern Front, was one of the most experienced units in the German army. Yet tonight, the battlefield felt unfamiliar. These Americans—whoever they were—did not behave like any enemy he had faced before. They did not regroup, they did not hesitate, and they did not wait for orders. They landed amidst chaos and immediately turned it into an attack.

Through the broken shutters of his command post, von der Heyde could see them moving through the fields—small groups, individual soldiers, some still half-tangled in their parachutes, all of them armed and advancing with frightening purpose. He heard scattered bursts of gunfire, grenades detonating at close range, shouts in English cutting through the night. It was disorienting. The Germans had expected confusion. They had expected lost, disorganized paratroopers stumbling through the dark. What they got instead was something entirely different—organized aggression erupting in every direction.

He turned toward his radio operator, shouting above the din. “Feindliche Fallschirmjäger überall! Everywhere!” The radio crackled in response, filled with fragmented reports—enemy movement near the crossroads, gunfire near the church, explosions by the orchard. Von der Heyde tried to make sense of it, but the pattern was impossible to track. The Americans weren’t fighting in conventional lines. They were attacking like hunters, striking quickly, vanishing into the night, then appearing again from another angle.

Out in the field, illuminated by the orange flash of a burning farmhouse, von der Heyde saw a sight that would haunt him for the rest of his life. A single American paratrooper was hanging from a tree, his parachute tangled in the branches, swaying gently above the ground. German soldiers surrounded him, raising their rifles. But before they could shoot, the man began firing—still strapped in his harness, firing downward with his M1 carbine. The Germans dove for cover. When his ammunition ran out, the American cut himself loose, dropped fifteen feet, and charged toward them, pistol in hand, screaming something that sounded like a battle cry. Six German soldiers fired at once. The American collapsed before he reached them.

Von der Heyde stood frozen. He had seen men fight bravely. He had seen soldiers die without fear. But this was something different—this was madness fueled by purpose. He was a veteran of Crete, had fought the British commandos, had faced the Red Army’s guards divisions in the East. Yet none of them had fought like this. These weren’t regular infantry. They were something else entirely—something he couldn’t yet name.

When dawn came, he found the body of the man who had charged his machine-gun nest. The American’s uniform was torn and bloodied, but on his shoulder, the insignia was still visible: a fierce bald eagle, wings spread wide, clutching arrows and a shield. The patch of the 101st Airborne Division—the Screaming Eagles. It was a symbol von der Heyde would never forget, and over the next eleven months, that patch would strike fear into German soldiers across Europe.

The 101st Airborne was unlike any other division in the U.S. Army. Born from an idea rather than tradition, it was activated on August 15th, 1942, at Camp Claiborne, Louisiana, under the command of Major General William C. Lee. It had no history to inherit, no regional identity to draw from, no legacy of past battles. Instead, it had something rarer: purpose. It was made up entirely of volunteers—men from across the country who had chosen one of the most dangerous roles in the military.

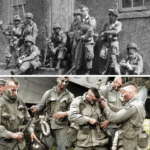

These were not conscripts or ordinary recruits. The men of the 101st were self-selected, drawn by the promise of challenge and the thrill of risk. They knew the statistics. They knew that airborne units suffered higher casualties than conventional infantry. They knew that parachute training broke bodies and spirits alike. Nearly forty percent of those who entered jump school washed out. Yet still they came—farm boys, factory workers, college athletes—all wanting to prove they could be part of something greater than themselves.

Training at Camp Claiborne and later at Fort Benning pushed them to physical and mental limits few soldiers had ever endured. They marched twenty miles in full gear under the Louisiana sun. They ran obstacle courses until they collapsed from exhaustion. They drilled with weapons, radios, and maps until their muscles remembered what fatigue would make them forget. Every man had to complete five qualifying jumps before earning his wings. Every man had to prove that he could not only fight, but think, lead, and survive on his own.

General Lee understood that airborne warfare demanded a new kind of soldier. Paratroopers would drop miles behind enemy lines, often scattered, disorganized, and surrounded. There would be no clear front, no reinforcements, no immediate command structure. Every man would need to be his own officer. And so, the training reflected that philosophy.

They were taught to make decisions instantly, to seize initiative, to act without waiting for orders. They were trained not to survive chaos—but to create it. Their instructors drilled them relentlessly on self-reliance. Every private learned how to read maps, use a compass, operate radios, and call for artillery strikes. Every sergeant learned how to command a platoon. Every officer learned that leadership was not authority—it was example.

Private First Class Don Malarkey of Easy Company, 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment, would later recall, “They didn’t teach us to land and wait for orders. They taught us to land and attack. Every man knew what the objective was. If you couldn’t find your squad, you found someone else’s. If you were alone, you kept moving toward the sound of the fight.”

This mindset—this culture of relentless initiative—was what set the 101st apart. It wasn’t just the training, the equipment, or even the discipline. It was the belief that the mission came before everything. When they hit the ground, they didn’t wait for clarity—they created it.

By the time of the Normandy invasion, the 101st Airborne Division had grown to 13,000 men, organized into three regiments—the 501st, 502nd, and 506th—supported by artillery, engineers, and glider infantry. Two years of preparation had forged them into one of the most cohesive, well-trained units in the U.S. military. Their morale was high, their confidence absolute, and their identity unmistakable. They wore the screaming eagle on their shoulders like a badge of destiny.

But what the Germans feared most wasn’t their numbers or their firepower. It was their unpredictability. Airborne troops didn’t fight by the rules. They didn’t wait for daylight or coordination. They came from the sky, struck hard, and disappeared. To the Wehrmacht, they seemed less like soldiers and more like phantoms—small, scattered bands appearing from nowhere, cutting communication lines, destroying convoys, attacking command posts, then vanishing back into the hedgerows before reinforcements could respond.

When the 101st dropped over Normandy, German intelligence underestimated them, assuming paratroopers would be confused and easy to neutralize. Instead, they faced hundreds of small, independent firefights that spread like wildfire across the countryside. Every barn, hedgerow, and field became a skirmish. Every crossroads a trap. The German army, trained to fight in structured formations, found itself disoriented by an enemy that refused to play by the rules.

By the time dawn broke over Sainte-Mère-Église, von der Heyde’s Sixth Regiment was no longer functioning as a cohesive unit. Communication lines were shattered. Outposts were overrun. Supply trucks burned on the roads. Everywhere he turned, there were reports of “small American groups” engaging in ambushes and counterattacks. The confusion was complete, the psychological toll immense.

For the German infantry, the patch of the screaming eagle came to mean one thing: chaos. The men who wore it didn’t retreat. They didn’t surrender. They landed in the middle of enemy territory and fought as if surrounded was the only way they knew how to fight.

And so, as dawn lit the shattered town of Sainte-Mère-Église, von der Heyde and the men of the Sixth Regiment began to understand what countless others across Europe would learn in the months to come. The screaming eagles were not just another division—they were a new kind of soldier. Their courage was reckless. Their tactics defied logic. And their presence meant one thing: trouble was coming.

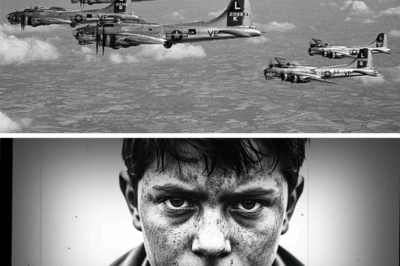

By June of 1944, the 101st Airborne Division had earned its place among legends. Thirteen thousand men trained to drop into the unknown, to fight surrounded, to improvise and survive where no support could reach them. As their planes flew through the night toward Normandy, no one could have known that in the hours to come, those men would change the course of the war—and that German infantry across Europe would come to fear the eagle patch more than any other insignia they would ever see.

D-Day. Chaos and violence were about to begin.

Continue below

June 6th, 1944. 02 to 15 hours. Sainte-Mère-Église, Normandy, France. Hermann Friedrich von der Heyde pressed himself against the stone wall of a Norman farmhouse, trying to comprehend what was happening. All around him, the night sky was filled with parachutes. Hundreds of them. Thousands.

American paratroopers were landing directly into his sixth parachute regiment’s positions, appearing from the darkness like vengeful ghosts. For 20 minutes, Vanderha’s men had been fighting scattered groups of Americans who seemed to materialize from nowhere. But these were not disoriented soldiers lost in the darkness. These Americans were attacking.

Immediately upon landing, often before even removing their parachute harnesses, they were engaging German positions with a level of aggression that defied tactical logic. Through his command post window, Fonder Heighta watched a scene that would haunt him for the rest of his life. A young American paratrooper, suspended in a tree and still trapped in his harness, was calmly firing his rifle at German soldiers attempting to reach him.

When he ran out of ammunition, he cut himself free, dropped 15 ft to the ground, drew his pistol, and charged toward a German machine gun position alone against six men. Vanderhaida’s radio man shot the American before he reached the position. But what Vandonderhaida couldn’t shake was the absolute fearlessness.

The German officer, a veteran of Cree and the Eastern Front, had faced Soviet guards divisions and British commandos. But he had never encountered soldiers who landed in the middle of enemy territory and immediately attacked without waiting for orders, without organizing, without even knowing where they were. What Vonderita didn’t know was that the screaming eagle’s patch on that dead American’s shoulder identified him as a member of the 101st Airborne Division. Over the next 11 months, German infantry across Europe would learn to recognize

that patch, and they would learn to fear it more than any other American Division insignia they encountered. The birth of the Screaming Eagles. The 101st Airborne Division was activated on August 15th, 1942 at Camp Claybourne, Louisiana. Unlike conventional infantry divisions that drew from regional populations or existing units, the 101st recruited volunteers from across the United States Army who wanted to be paratroopers.

The self- selection process meant that the division began with soldiers who actively sought the most dangerous assignment in the army. Men who volunteered for parachute training knew the statistics. Training was brutal with a 40% attrition rate. Combat casualty rates for airborne units exceeded conventional infantry by significant margins. Yet thousands volunteered.

Major General William C. Lee, the division’s first commander, established standards that exceeded regular army requirements. Every paratrooper had to complete five qualifying jumps. Physical fitness requirements were extreme. Forced marches of 20 miles in full equipment were routine. The training was designed to eliminate anyone who lacked absolute commitment.

But physical capability alone did not make the 101st exceptional. What separated them from other divisions was tactical philosophy. Airborne doctrine emphasized initiative, aggressive action, and independent operations. Paratroopers expected to land scattered across enemy territory, separated from their units, often surrounded.

They trained to fight immediately, to organize themselves, to accomplish missions without waiting for orders from higher command. Private First Class Don Malarkey, who would serve with Easy Company 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment throughout the war, later described the training philosophy. They didn’t teach us to land and wait for orders. They taught us to land and attack.

Every one of us knew how to read a map, use a compass, call artillery, operate a radio. Every private was trained to do a sergeant’s job. Every sergeant could command a platoon. We didn’t need officers to tell us what to do. We already knew. This emphasis on individual capability and initiative would prove decisive in combat.

When German forces scattered American paratroopers across Normandy, expecting confusion and disorder, they instead faced thousands of highly trained soldiers who immediately began attacking anything German they could find. By June 1944, the 101st Airborne Division numbered approximately 13,000 men organized into three parachute infantry regiments, the 501st, 505th, and 506th, plus artillery, engineers, and support units. They had trained for two years.

They were ready, and they were about to demonstrate why German infantry would learn to dread the sight of the screaming eagle. D-Day. Chaos and Violence. June 6th, 1944. The 101st Airborne Division’s mission for D-Day was ambitious to the point of seeming impossible. drop behind Utah Beach.

Secure causeway exits to allow the Fourth Infantry Division to move inland, destroy bridges to prevent German reinforcement, and establish defensive positions, all while scattered across enemy-held territory in darkness. The drop was a disaster by conventional military standards. High winds, anti-aircraft fire, and pilot errors scattered paratroopers across 50 square miles of Norman countryside. Entire sticks landed miles from their designated drop zones.

Some paratroopers drowned in flooded fields. Others landed directly on top of German positions. Unit cohesion, the foundation of conventional military operations, simply did not exist. But the 101st had trained for exactly this chaos. And what happened next would become legendary in military history.

Scattered paratroopers immediately began moving toward objectives when they couldn’t find their assigned units they joined whoever they encountered. Officers led men they had never met. Sergeants commanded soldiers from different companies and everyone attacked. Lieutenant Colonel Robert Wolverton, commanding Third Battalion, 506th Parachute Infantry, landed three miles from his drop zone with only a handful of his men.

Rather than waiting to assemble his battalion, he organized the 20 paratroopers he could find, attacked the nearest German position, and accomplished his mission of destroying a key bridge. He was killed leading that attack, but his objective was achieved by a scratch force less than 5% the size of his original battalion.

This pattern repeated across the battlefield. Small groups of paratroopers, often fewer than 20 men, attacked German positions that conventional doctrine would require company or battalion strength to assault. They used speed, surprise, and overwhelming aggression to compensate for lack of numbers.

Oberist Gunther Keel, commanding the 9/119 Grenadier Regiment defending the causeways behind Utah Beach, sent a report to 84th Corps headquarters that morning that revealed German confusion. We are under attack by American airborne forces at multiple locations. Enemy strength unknown. Attacks are uncoordinated but aggressive. Small groups of enemy infantry appear everywhere, attacking without apparent regard for their own safety.

We cannot determine their objectives or main effort. Request immediate reinforcement. What Ke didn’t understand was that there was no main effort. There were thousands of individual efforts. Each paratrooper attacking whatever target presented itself. The chaos that disrupted German defensive coordination was the result, not a failure, of airborne operations.

By the end of D-Day, the 101st Airborne Division had accomplished most of its primary objectives despite losing over 1,000 men killed, wounded, or missing. More significantly, they had seized German attention and prevented reinforcement of the beaches at the critical moment.

The fourth infantry division came ashore at Utah Beach and suffered fewer than 200 casualties, the lightest of any D-Day beach, largely because 101st paratroopers had paralyzed German response. Carantan, the test of courage, June 8th through 13th, 1944. The town of Karantan sat at a critical junction between Utah and Omaha beaches. If German forces held Carant Tan, they could prevent the two American beach heads from linking up.

The mission to capture Carant Tan went to the 101st Airborne Division, still scattered and under strength from the D-Day drop. The 502nd Parachute Infantry Regiment commanded by Colonel Robert Sink, received the mission to seize the town. They would have to advance along elevated causeways through flooded fields exposed to German fire from both flanks. It was a tactical nightmare.

Exactly the kind of situation that conventional military wisdom said to avoid. The paratroopers attacked. On June 10th, First Battalion advanced along the causeways under intense German fire. Men were shot off the narrow elevated roads and fell into the flooded fields where the weight of their equipment drowned them.

German machine guns and mortars turned the causeways into killing grounds. Lieutenant Richard Winters commanding Easy Company 506th Regiment later described watching the 502s attack. They walked into hell. The Germans had perfect fields of fire. Every meter of that causeway was covered. We watched men fall and more men took their place and they kept going. I have never seen such courage.

The assault stalled just short of Carantan. But on June 12th, the attack resumed with support from the 501st regiment. This time, paratroopers infiltrated through the flooded fields rather than advancing along the causeways. They waited through chestde water, maintaining noise discipline that allowed them to approach German positions undetected.

The fighting in Carantan itself was house-to-house, brutal and close range. Paratroopers cleared buildings with grenades and bayonets. German Falerm Jerger elite paratroopers themselves defended with determination. For two days, the battle raged through narrow streets and shattered buildings. On June 13th, Kerranton fell, but immediately German forces counterattacked with elements of the 17th SS Poner Grenadier Division.

German armor and mechanized infantry struck the exhausted paratroopers holding the town. Without tanks or significant anti-tank weapons, the 101st faced SS troops and armor with rifles, bazookas, and courage. The defensive line bent. It nearly broke, but it held. Paratroopers fought from buildings, from ditches, from hedge rows.

When German armor approached, they attacked with bazookas at ranges so close that German tank commanders could see the Americans faces. When ammunition ran low, they used captured German weapons, and they held. Combat Command A of the Second Armored Division arrived in time to stabilize the line and drive back the German counterattack. But the critical hours when the 101st held alone against SS armor and infantry demonstrated something that German commanders would remember. American paratroopers did not break.

When surrounded, they fought harder. When outnumbered, they attacked. When conventional wisdom said to retreat, they held. ESS Standard Furer Verer Oendorf commanding the 17th SS division wrote in his afteraction report. American airborne troops demonstrate exceptional determination. They held Carantan against our armored assault for 3 hours before being reinforced.

Casualties inflicted on our forces exceeded expectations. These are not ordinary American infantry, but elite troops comparable to our own falser. Recommend avoiding direct engagement when possible. That last line from an SS commander recommending his forces avoid direct engagement with Americans represented a shift in German tactical thinking. The Vermach had entered Normandy confident in its superiority.

30 days later, German officers were recommending that their elite SS units avoid fighting the screaming eagles. The Normandy campaign from D-Day through early July, the 101st Airborne Division fought continuously in Normandy. They held defensive positions against German counterattacks. They conducted offensive operations through the Bokehage hedge.

They existed in a state of constant combat that would have broken many conventional divisions. The casualty rate was staggering. By early July, the division had suffered over 4,000 casualties, nearly onethird of its strength. Some companies were down to 50% of authorized strength. Some platoon were commanded by sergeants because all the officers were dead or wounded. Yet, the division maintained combat effectiveness.

German forces facing the 101st consistently reported that American paratroopers fought differently from conventional infantry. A captured operations order from the 352nd Infantry Division warned subordinate units. American airborne forces in this sector maintain aggressive posture despite heavy casualties.

They conduct frequent patrols and raids. They respond to contact with immediate counterattack. Defensive positions should be heavily fortified and constantly manned. These troops do not respect tactical disadvantage. That last observation that paratroopers did not respect tactical disadvantage.

Captured something essential about the 101st’s combat effectiveness. They attacked when outnumbered. They held when surrounded. They accomplished missions that conventional units would consider impossible. Not because they were superhuman, but because they were exceptionally trained and absolutely refused to accept defeat. In late June, the 502nd regiment conducted a night attack against German positions in the village of Dove.

The attack was launched with minimal preparation, limited intelligence, and no artillery support. By conventional standards, it should have failed. Instead, paratroopers infiltrated German defenses in darkness, struck multiple positions simultaneously, and seized the village before German forces could organize effective resistance.

Overlit Hans Schmidt, whose company defended Dove, survived and was captured. His interrogation transcript revealed German frustration. We held strong positions. We had machine guns, mortars, clear fields of fire. The Americans attacked at night without artillery preparation, without armor. They should have been slaughtered. Instead, they infiltrated our positions and destroyed us.

We could not track them. We could not predict them. These airborne soldiers fight without rules. By July 29th, when the 101st was withdrawn from Normandy for rest and refitting, they had been in continuous combat for 53 days. No other division in the European theater had sustained combat operations for that long without relief. Their casualties exceeded 33%.

But they had never failed to accomplish a mission. They had never broken. and they had created a reputation among German forces that would influence German tactical planning for the remainder of the war. If you’re fascinated by these detailed accounts of World War II’s most elite units and want to explore more stories about the battles that shaped history, make sure to subscribe to the channel and hit the notification bell so you never miss an episode.

Operation Market Garden, September 17th through 25th, 1944. Operation Market Garden. Field Marshall Montgomery’s ambitious plan to end the war by Christmas required airborne forces to seize bridges across the Netherlands, creating a corridor for British armor to drive into Germany. The 101st Airborne Division received the mission to capture bridges and hold the 15-mi corridor between Antoven and Veil.

Unlike D-Day, this would be a daylight drop with better unit cohesion, but the mission required holding an extended position against German counterattacks for days while waiting for British armor to advance. The drop on September 17th went well. The division captured most of its objectives within hours.

The bridge at sun was blown by German engineers just as paratroopers reached it, but engineers quickly constructed a replacement. By nightfall on September 17th, the 101st held the corridor and waited for British XXX Corps to advance from the south. What followed was a week of desperate fighting as German forces attempted to cut the corridor and isolate the airborne divisions.

The 101st found itself defending a 15-mi stretch of road against attacks from all directions. The 501st regiment held Veagel against repeated attacks by German armor and infantry. The 506th held best and sent Uden Road. The 502nd held the southern end of the corridor. The fighting was continuous and brutal.

German forces recognizing the strategic importance of the corridor through everything available against the paratroopers, armor, artillery, infantry, everything. The 101st, designed for rapid assault operations, found itself fighting a conventional defensive battle against superior numbers and firepower. On September 22nd, German forces cut the corridor near Veghell.

For 36 hours, the 101st was surrounded and cut off from supply. British armor fought to reopen the road while paratroopers held against continuous German attacks. Ammunition ran low. Medical supplies were exhausted, casualties mounted, yet the paratroopers held. General Major Walter Pop, commanding the 59th Infantry Division that attacked Vegel, described the fighting in his post-war interrogation.

We attacked the American positions with three regiments supported by armor and artillery. We achieved local penetrations, but could not break their line. The Americans counterattacked immediately anytime we gained ground. They fought from buildings, from ditches, from anywhere they could find cover.

Even when we destroyed their positions, they continued fighting from the rubble. These airborne troops were the most tenacious enemy I encountered in the war. The corridor was reopened on September 24th. Operation Market Garden ultimately failed to achieve its strategic objectives with British paratroopers at Arnum being destroyed.

But the 101st accomplished every mission assigned. They held the corridor. They defeated every German attempt to cut the road, and they demonstrated again that American paratroopers could not be broken by conventional military force. The division suffered over 2,000 casualties in 8 days of fighting. But German forces attacking the corridor suffered over 5,000 casualties without achieving their objective.

The 101st had proven they could fight defensive battles as effectively as offensive operations. The Arden and Bastoni. December 16th, 1944. The 101st Airborne Division was resting in camps near Rems, France, recovering from Market Garden. They were under strength with many replacements who had never jumped into combat. They expected weeks of rest before returning to combat.

Then came the German Ardenis offensive. Hitler’s last gamble. 190,000 German soldiers supported by hundreds of tanks struck through the Arden’s forest with the objective of splitting the Allied armies and recapturing Antworp. American forces were caught completely by surprise and began retreating in disorder. On December 18th, the 101st received emergency orders.

Load on trucks immediately. Move to Bastonia, Belgium. Hold the town against German advance. No time for preparation. No time for intelligence gathering. Just move and hold. The division arrived in Bastonia on December 19th, just ahead of advancing German forces. Brigadier General Anthony McAuliffe, acting division commander, while General Maxwell Taylor was in the United States, assessed the situation. German forces were approaching from three directions.

The American units that had been holding the area were retreating in disorder. The 101st would be surrounded within hours. McAuliff’s orders were simple. Dig in, hold, do not retreat under any circumstances. The town of Bastonia sat at a critical road junction. If German forces captured it, their advance could continue.

If the paratroopers held it, the German offensive would stall. Everything depended on the screaming eagles. By December 21st, the 101st was completely surrounded. German forces, primarily from the fifth panzer army and seventh army, outnumbered the defenders by more than 3 to one. They had armor, artillery, and supplies.

The paratroopers had whatever they carried in, minimal artillery support, and dwindling ammunition. The Germans expected the Americans to surrender. On December 22nd, German officers approached under a flag of truce with a surrender demand. The message warned that without surrender, total annihilation was certain. General McAuliff’s response became legendary. Nuts. The German officers confused by the slang asked for clarification.

Colonel Joseph Harper delivering the response explained, “It means go to hell and tell your commander if he wants Bastonia, come and take it.” What followed was one of the most celebrated defensive battles in American military history. For 6 days, the 101st Airborne Division held Bastonia against overwhelming odds.

They were outnumbered, surrounded, low on ammunition, low on medical supplies, low on food. German artillery pounded them continuously. German armor probed their positions constantly. The weather was freezing with heavy fog and snow that prevented air supply or support. The paratroopers held. They fought from foxholes in frozen ground.

They repelled attacks by German armor with bazookas and determination. They stretched ammunition by enforcing fire discipline that would have been unthinkable in conventional units. They treated wounded in aid stations that ran out of medical supplies and operated by candle light.

The defense of Bastonia was organized around the division’s three regiments establishing defensive perimeters. The 50ohirst held the north and east. The 506th held the west. The 502nd held the south. Each regiment faced continuous pressure from German forces attempting to break through. On December the 23rd, weather cleared enough for C-47 transport aircraft to drop supplies.

The paratroopers watched supply parachutes descending and cheered, knowing they could continue fighting. But they had never doubted they would hold. Even when surrounded, even when outnumbered, even when running low on everything, the screaming eagles never considered surrender. The psychological impact on German forces was profound.

Troops that had been told they were crushing American resistance found themselves stopped cold by a single division. The Panzer Lair Division, one of Germany’s elite armored formations, attacked Bastonia multiple times and was repeatedly thrown back with heavy losses. General Litman Fritz Berline, commanding Panzer Lair, told interrogators after the war. Bastonia was supposed to fall in one day. It was just a town defended by scattered American remnants.

Instead, we found an entire airborne division dug in and determined to hold. We attacked for 6 days. We never broke their line. The Americans fought from every building, every foxhole, every position. They had limited ammunition, but used it with terrible effectiveness. They had few anti-tank weapons, but destroyed our tanks at suicidal ranges. These airborne troops were the finest defensive fighters I ever faced.

On December 26th, elements of Patton’s Third Army broke through German lines and relieved Bastonia. The siege was over. The 101st had held. And in holding, they had ruined Hitler’s last offensive. German forces, unable to capture Bastonia, could not maintain their advance.

The Arden’s offensive, which had aimed to split the Allied armies and change the war’s outcome, had been stopped by paratroopers in frozen foxholes who simply refused to surrender. The Battle of Bastonia became synonymous with American determination and courage. But for German infantry who had attacked the town, it became something else. Proof that the 101st Airborne Division could not be broken.

Proof that even when surrounded and outnumbered, the Screaming Eagles were more dangerous than conventional divisions with superior numbers and firepower. Why Germans feared the 101st. By early 1945, German tactical directives specifically mentioned the 101st Airborne Division as a priority threat requiring special attention. But why did German infantry fear this particular division more than others? First, aggressive mentality.

The 101st attacked as default behavior. When contacted by German forces, conventional American divisions would establish defensive positions and return fire. The 101st counteratt attacked immediately, turning defensive situations into offensive actions that disrupted German operations. Second, independent capability.

Every paratrooper was trained to function independently. When German forces succeeded in fragmenting American units, conventional divisions lost effectiveness. The 101st maintained combat power even when scattered with small groups continuing to fight effectively. Third, battlefield adaptability. Paratroopers trained for chaotic airborne operations adapted to conventional warfare better than conventional infantry adapted to airborne chaos.

The 101st fought effectively in every type of combat from raids to defensive battles to urban warfare. Fourth, refusal to surrender. German forces had learned that many American units would surrender when surrounded or out of ammunition. The 101st never surrendered. At Bastonia, surrounded and outnumbered, they fought harder.

This created psychological uncertainty for German commanders who could not predict when Americans would break. Fifth demonstrated success. The division had never failed to accomplish a mission. D-Day objectives secured. Carantan captured. Market garden corridor held. Bastonia defended. This record created an aura that preceded them into combat and influenced German tactical planning. Sixth casualty infliction.

The 101st killed German soldiers at rates exceeding conventional American divisions. At Bastonia alone, the surrounded paratroopers inflicted over 5,000 casualties on attacking German forces while suffering approximately 2,000 themselves, a favorable ratio despite being surrounded and outnumbered. A captured German intelligence assessment from March 1945 found in 15th Army files analyzed American divisions and their combat effectiveness.

The section on the 101st concluded the American 101st Airborne Division represents the highest quality American combat formation unit demonstrates exceptional cohesion, aggressive tactics and determination. All personnel are volunteers who have completed rigorous training.

Combat record shows consistent achievement of objectives against superior enemy forces. The division has never been defeated in defensive operations and maintains offensive capability even when significantly weakened by casualties. When the 101st is identified in a sector, expect aggressive American operations and prepare for defense against elite assault troops. Recommend avoiding engagement when possible and employing overwhelming force when engagement is necessary.

That assessment written by German professional intelligence officers represented ultimate recognition of the division’s effectiveness. German forces were being told to avoid fighting the 101st Airborne when possible and to use overwhelming force when fighting them was necessary. This was the same advice given for facing SS divisions or Soviet guards units. Recognition that the Screaming Eagles belonged in the top tier of combat formations.

This deep exploration of the 101st Airborne’s combat record shows why they became legendary. For more detailed analysis of World War II’s most elite units and the battles they fought, subscribe to the channel and turn on notifications for new content every week. The final campaigns. After Bastonia, the 101st Airborne Division continued fighting through the final months of the war.

They participated in the reduction of the Kulmar pocket, drove into Germany itself, and ultimately captured Hitler’s eagle’s nest at Burkisen. Throughout these operations, German forces continued to recognize the division’s distinctive capabilities. Even in the war’s final weeks, when German military effectiveness was collapsing, units facing the 101st fought with greater determination than those facing conventional divisions.

The statistics from these final months were revealing. German casualty rates when fighting the 101st exceeded casualties from engagements with conventional American divisions by approximately 30%. German units facing the screaming eagles surrendered less frequently than when facing other divisions, suggesting that German commanders believed fighting was preferable to the alternative of being overrun by paratroopers.

The human cost and legacy. The 101st Airborne Division’s effectiveness came a terrible human cost. Of approximately 15,000 men who served with the division during the war, over 8,000 became casualties. The casualty rate exceeded 50%, far higher than conventional infantry divisions. This rate reflected the division’s employment.

They jumped into Normandy against the strongest German defenses. They held Bastonia when surrounded. They fought continuously without the rest periods given to conventional divisions. They were assigned the hardest missions because commanders knew they would accomplish them. But those who served with the screaming eagles, particularly those who survived multiple campaigns, spoke with pride about their service.

They had proven that American soldiers, properly trained and properly led, could defeat the Vermach’s best troops under the worst conditions. Private First Class Don Malarkey, who served with easy company from D-Day through the war’s end, reflected decades later on what made the division exceptional.

We weren’t better soldiers because of equipment or numbers. We were better because every man in the division believed we were better. That confidence came from training that made us capable of doing things other soldiers couldn’t do. When we landed in Normandy, scattered across enemy territory, we didn’t panic, we attacked.

When we were surrounded at Bastonia, we didn’t surrender. We held. That’s what made us the Screaming Eagles. Postwar assessments by both American and German military professionals consistently rated the 101st among the most effective divisions in the European theater. The division received four campaign streamers and two presidential unit citations recognizing its exceptional performance.

But perhaps the most telling assessment came from German officers surveyed after the war about which American units they considered most dangerous. The 101st Airborne Division ranked at the top ahead of larger armored divisions and other airborne divisions. General Litman Fritz Berline whose panzer lair division fought the 101st at multiple points provided this assessment during his interrogation.

Of all American divisions I faced, the 101st Airborne was the most formidable. They combined excellent training with aggressive leadership and soldiers who simply would not quit. At best, we had them surrounded, outnumbered 3 to one with superior armor and artillery. We should have destroyed them in two days. Instead, they stopped our entire offensive.

That tells you everything about the quality of that division. Conclusion. The story of why German infantry feared the 101st Airborne Division more than any other is a story of demonstrated superiority earned through training, courage, and unrelenting determination. German soldiers did not fear the screaming eagles because of propaganda or mythology.

They feared them because in every encounter from Normandy to Boston to Germany itself, the 101st demonstrated capabilities that German forces could not match. They landed in Normandy scattered and surrounded and they attacked. They defended Carranton against SS armor with rifles and bazookas and they held.

They were surrounded at Baston, outnumbered and low on everything, and they fought harder. Every engagement reinforced the lesson that the 101st could not be defeated by conventional means. From the perspective of a German infantry soldier, the sight of the screaming eagle patch meant facing an enemy that would not retreat, that would not surrender, that would not break.

It meant fighting soldiers who were better trained, more aggressive, and more determined than conventional American infantry. It meant accepting that the coming battle would be harder, bloodier, and more costly than fighting other divisions. German commanders learned through painful experience to respect the 101st Airborne.

They distributed tactical guidance warning subordinates about the division’s capabilities. They reinforced positions when the division was identified in their sector. They requested additional support before engaging, and when possible, they avoided fighting the screaming eagles all together. This fear was not cowardice, but professional respect for an enemy that had proven itself superior in every measurable way.

The Vermacht, which had conquered most of Europe, which prided itself on tactical excellence and warrior culture, recognized in the 101st Airborne, an opponent that matched or exceeded their own elite formations. The paratroopers who jumped into Normandy, who held Bastonia, who fought through France, Holland, and Germany, created a legacy that endures. Modern military forces study their operations.

Tactics they pioneered remain relevant. Standards they established continue to challenge new generations of soldiers. But the most enduring legacy is the respect they earned from the enemy they defeated. German infantry learned through battle after battle that the screaming eagles represented the finest American combat soldiers of World War II. They were volunteers who sought the hardest missions.

They were paratroopers who trained to standards exceeding conventional forces. They were warriors who proved that American soldiers, properly prepared and properly led, were second to none. When German infantry saw the screaming eagle patch, they knew they faced an enemy that would fight harder, endure more, and accomplish missions that seemed impossible.

They knew that conventional tactics would not work, that numerical superiority might not be enough, that victory would require everything they could give and possibly more than they had. The 101st Airborne Division earned German fear through demonstrated capability in combat. From their first jump into Normandy through the final days in Germany, they proved themselves in battle against Germany’s finest troops.

They were outnumbered at Bastonia and won. They were scattered at Normandy and won. They faced SS Armor at Carranton and won. They never surrendered, never broke, never failed. That record written in German fear and American courage remains the ultimate testament to the screaming eagles.

They were not the largest division. They were not the most heavily equipped, but they were by the admission of the enemy. They defeated the most feared American division in the European theater. The German infantry who faced them and survived carried that knowledge forever. The paratroopers who wore the screaming eagle and survived earned a place among history’s finest combat soldiers.

Together they wrote a chapter of military history that proves a fundamental truth. In warfare, victory belongs not to the largest or most numerous force, but to the best trained, best led, and most determined. The 101st Airborne Division embodied that truth, proving it in frozen foxholes at Bastonia, in hedge of Normandy, in streets of Karentan.

They proved it against Vermach infantry, SS armor, falser paratroopers. They proved it when surrounded, when outnumbered, when conventional wisdom said defeat was certain. The screaming eagles taught the German Vermach a lesson. That lesson cost Germany dearly. American soldiers, when trained to elite standards and led by capable officers, were equal to or better than any soldiers in the world.

That lesson learned in blood across Europe remains the 101st Airborne Division’s greatest legacy and the source of the fear they inspired in every German soldier who saw their patch and knew that the hardest fight of their life was about to again.

News

CH2 Wehrmacht Major Fled the Eastern Front — 79 Years Later, His Buried Field Chest Was Found in Poland

Wehrmacht Major Fled the Eastern Front — 79 Years Later, His Buried Field Chest Was Found in Poland It…

CH2 How One Woman Exposed the Hidden Gun That Shot Down 28 Planes in 72 Hours at Iwo Jima

How One Woman Exposed the Hidden Gun That Shot Down 28 Planes in 72 Hours at Iwo Jima February…

CH2 The 96 Hour Nightmare That Destroyed Germany’s Elite Panzer Division

The 96 Hour Nightmare That Destroyed Germany’s Elite Panzer Division July 25th, 1944. 0850 hours. General Leutnant Fritz Berlin…

CH2 One Of Many Unsung Heroes – The 13-Year-Old Boy Who Guided Allied Bombers to Target Using Only a Flashlight on a Rooftop

One Of Many Unsung Heroes – The 13-Year-Old Boy Who Guided Allied Bombers to Target Using Only a Flashlight on…

CH2 June 4, 1942 At 10:30 AM: The Five Minutes That Destroyed Japan’s Chance Of Winning WW2

June 4, 1942 At 10:30 AM: The Five Minutes That Destroyed Japan’s Chance Of Winning WW2 June 4th, 1942,…

CH2 The Moment That Almost Changed History: Why Patton Wanted to Attack the Soviets in 1945 Revealed – The Warning Eisenhower Refused to Hear

The Moment That Almost Changed History: Why Patton Wanted to Attack the Soviets in 1945 Revealed – The Warning Eisenhower…

End of content

No more pages to load