Why American Submarines Strangled Japan, While Japanese Subs Could Not Do Anything – The Man Who Opened The Door

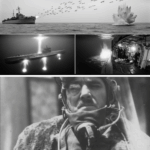

At 07:30 hours on July 24, 1943, Lieutenant Commander Lawrence Daspit stood rigid in the conning tower of USS Tinosa, the salty morning breeze biting at his face as the periscope lens framed the hulking silhouette of a Japanese tanker, the Tonan Maru number three. She was a 19,000-ton behemoth, dead in the water two thousand yards away, her hull streaked with rust and sun-drenched in the early light. No escort vessels patrolled nearby. The sea was calm, almost mockingly so, as if it conspired with the immobile tanker to frustrate every calculated movement Daspit might make. This was the scenario every submarine commander dreamed of: a perfect, unhurried kill. He could almost smell the oil and salt on the deck of the tanker, could read the painted letters of its name through the scope. There was no time pressure, no danger looming. The target was a sitting duck, yet fate—or more accurately, faulty engineering—was about to mock him in ways he could never have imagined.

Daspit had already fired two torpedoes in an earlier salvo, strikes intended to cripple the Tonan Maru. The first salvo had delivered direct hits, but now, in the light of day and the calm of the sea, he prepared for what should have been the final act. Tinosa maneuvered into textbook attack position, perpendicular to the tanker’s beam at 875 yards—a distance so close that every port hole and every rust streak was visible through the periscope. Daspit’s crew worked with the precision of a well-oiled machine, nerves taut yet disciplined, as he gave the order: fire.

The first torpedo slid from the tube with a hiss and a bubble trail, arcing gracefully through the water toward the tanker’s hull. Thirty seconds later, it struck with a metallic clang that reverberated through Tinosa’s steel skin. The crew’s ears rang with the sound of metal on metal. But there was no explosion. Daspit’s jaw tightened. He fired again. Another clang. Another dud. A third, a fourth, a fifth—each torpedo leaving its mark on the tanker’s hull but failing to detonate. The metallic clangs echoed in the cramped spaces of the submarine, each one a reminder that the weapon designed to end the fight had betrayed them utterly. Eleven more torpedoes followed, each a perfect shot, each a hollow, disheartening impact. The tanker floated, taunting, untouched by the firepower meant to obliterate her.

In the torpedo room, disbelief settled over the men like a fog. The fire control team exchanged grim looks, knowing instinctively that something was catastrophically wrong. Daspit, though outwardly calm, felt a cold dread seep into his bones. They had started this engagement with sixteen torpedoes. The first salvo had crippled the target, but now, eleven successive torpedoes had failed, one after another. And with just one torpedo left, the grim calculus of survival and accountability began to press against him. He ordered the crew to surface and head back to Pearl Harbor. The last torpedo, the evidence of the Mark 14’s fatal flaws, would be preserved, brought home to reveal a systemic failure that had already cost American lives and missions.

What Daspit could not know at that moment was that this disaster would finally force the Navy’s hand. For twenty-one months, American submarine crews had been waging war with weapons that often didn’t work, their reports dismissed, their concerns minimized. The Mark 14 torpedo, the pride of the Bureau of Ordnance, was fundamentally defective. The magnetic exploder often failed, the contact detonator misfired, and the depth-keeping mechanism caused torpedoes to run far deeper than set, passing harmlessly beneath their targets. These weren’t minor inconveniences—they were life-and-death failures that transformed each patrol into a gamble against equipment as much as against the enemy. Every dud torpedo was a chance for Japanese ships to survive, to deliver troops, fuel, and supplies to the front, while American submariners faced mounting frustration and mortal risk.

Long before Daspit’s failed attack, other commanders had sensed the catastrophic pattern. Lieutenant Commander Tyrell Jacobs of USS Sargo had discovered it on December 24, 1941, scarcely three weeks after Pearl Harbor. He fired eight torpedoes at Japanese merchant vessels, watched as each struck the hull, heard the metallic clangs reverberate through his sonar system—and watched as the ships sailed away undamaged. Jacobs filed a meticulous report, detailing the failures and urging corrective action. The Bureau of Ordnance’s response was predictable: the problem was not the torpedoes. It was human error. The reports from competent, trained submarine skippers were dismissed, often with the same bureaucratic stubbornness that had plagued the Navy’s ordnance division for decades.

Lieutenant Commander Richard Voge of USS Sailfish, Lieutenant Commander Lewis Parks of USS Pompo, and Lieutenant Commander James Co of USS Skipjack—all faced similar frustrations. Voge watched fourteen torpedoes run beneath targets; Parks fired six torpedoes in perfect formation only to see each pass harmlessly under a freighter; Co attacked an aircraft carrier on Christmas Day 1941, all torpedoes failing to explode. Reports of torpedoes running too deep, of duds on contact, of premature explosions were consistent across the Pacific, across different commanders and crews, and yet the Bureau clung to its original tests and assumptions, ignoring empirical evidence from the field.

By early 1942, the gravity of the situation was unmistakable. American submariners were effectively disarmed in terms of their primary offensive weapon. The Japanese, by contrast, were unhindered. Their merchant convoys traversed the Pacific with near impunity, and their own submarines—though fewer in number—did not suffer the same catastrophic equipment failures. American subs were hamstrung not by lack of courage or skill, but by flawed engineering, mismanagement, and institutional obstinacy.

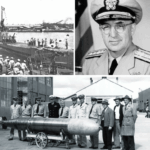

The breakthrough, ironically, came from a man who understood the value of experience, the importance of listening, and the necessity of trusting skilled personnel in the field. Rear Admiral Charles Lockwood, commanding the submarine forces in the Southwest Pacific from Fremantle, Australia, arrived in May 1942 to find a demoralized and frustrated cadre of commanders. At 52, Lockwood was a career submariner, hardened by decades at sea, familiar with the nuances of boat handling, torpedo mechanics, and crew dynamics. He was known affectionately as “Uncle Charlie” by his men, a testament to his willingness to hear grievances and champion their concerns when warranted.

Unlike many flag officers, Lockwood did not dismiss reports of torpedo failures as incompetence or bad luck. He investigated personally, tested torpedoes under operational conditions, and reviewed combat reports with an analytical eye. He recognized the pattern that others had ignored: the Mark 14 was failing consistently in multiple theaters, under varied conditions, and against different types of targets. By acting decisively, Lockwood would become the central figure in correcting a systemic flaw that had crippled the U.S. submarine campaign in its earliest years. His willingness to challenge the Bureau’s entrenched assumptions set the stage for American submarines to finally operate with lethal effectiveness.

Until that point, however, the consequences of inaction were stark. Each failed torpedo represented not just a missed opportunity but a mortal threat to the crews aboard. American submariners faced not only the enemy but their own defective equipment. The frustration and danger compounded, leading to tense patrols, sleepless nights, and an increasing sense that victory in the Pacific relied as much on overcoming internal failures as it did on defeating the Japanese navy. Meanwhile, Japanese shipping continued largely unmolested, supplying their war machine and prolonging the conflict.

The situation aboard USS Tinosa that July morning was emblematic of the larger struggle. Daspit’s precision had been flawless. His positioning had been textbook. Every shot had been correct. Yet he had witnessed firsthand the deadly consequences of bureaucratic and technical failures, a lesson that had been repeated thousands of times across the Pacific. One final torpedo, carefully preserved, would carry the proof back to Pearl Harbor, the tangible evidence that would eventually force acknowledgment, testing, and correction. It was a stark, visceral demonstration of the gap between intent and capability, a gap that had already cost lives, delayed strategic victories, and emboldened an enemy.

American submarines, once freed from the constraints of malfunctioning ordnance, would go on to strangle Japan’s economy, cutting off supplies, sinking merchant shipping, and turning the tide of the Pacific War. Japanese submarines, despite technological sophistication and reliable torpedoes, would fail to exploit strategic opportunities, hampered by doctrinal misjudgments and ineffective operational choices. The contrast between the two forces illustrates a fundamental truth about war: victory depends not merely on hardware or courage but on the alignment of strategy, trust, and the willingness to confront inconvenient truths.

Aboard Tinosa, as the sea reflected the harsh glare of the morning sun, the last torpedo rested silently in its tube. The metallic clangs of the previous eleven failures still echoed in the minds of the crew. Daspit’s eyes scanned the calm horizon, contemplating both the injustice of their situation and the potential of change. The Pacific remained wide, dangerous, and full of opportunity, but only if the Navy could reconcile with the failings that had haunted its submarine fleet since the war’s earliest days.

The proof rested in that last torpedo, the testimony of steel and explosive, waiting to reveal the truth to a world that had refused to listen. The lessons learned from Tinosa’s engagement—and countless others like it—would reshape naval warfare in the Pacific. Yet in that moment, with the Tonan Maru listing gently in the sunlight, the war’s outcome remained uncertain, the danger imminent, and the triumph of American submarines still a work in progress.

Continue below

At 07:30 hours on July 24, 1943, Lieutenant Commander Lawrence Daspit stood in the conning tower of USS Tinosa, watching through his periscope as a 19,000 ton Japanese tanker, Tonan Maru number three, sat dead in the water 2,000 yd away. He had already put two Mark1 14 torpedoes into her from his first salvo. The tanker was crippled, listing to starboard, dead in the water.

No escort vessels were in sight. The sea was calm. The morning sun glinted off the tanker’s rust streaked hull. Daspit had plenty of time. This was the perfect kill. The kind submarine commanders dreamed about. A sitting duck target. No time pressure, no threats, just a disabled ship waiting to be sunk.

He maneuvered Tinosa into the textbook firing position, perpendicular to the targets beam at 875 yds. Range so close he could see the ship’s name painted on the bow through the periscope. He could count the port holes. This was point blank range for a submarine attack. He ordered his crew to fire.

The first torpedo left the tube. 30 seconds later, it struck the tanker with an audible clang that echoed through Tinosa’s hull. The crew heard it clearly. Metal hitting metal. No explosion. Daspit fired another. Another another solid hit. Another metallic clang. No explosion. He fired a third torpedo. Same result.

A fourth. A fifth. A sixth. A seventh. An eighth. A 9th. A 10th. An 11th. Every torpedo ran true. Every torpedo hit exactly where Daspit aimed. The crew could hear each impact through the hull. Clang, clang, clang. Like hammers striking an anvil. Not one exploded.

The crew in the torpedo room knew something was wrong. The fire control team knew something was wrong. Daspit knew something was wrong, but they kept firing. Maybe the next one would work. It didn’t. Daspit had started this engagement with 16 torpedoes. His first salvo of four torpedoes produced two hits that crippled the tanker.

Then he fired 11 more, one at a time, from a perfect firing position. 11 direct hits, 11 metallic clangs echoing through the hull. 11 duds, every torpedo struck exactly where he aimed. Not one exploded. The tanker sat there, damaged, but afloat, mocking them. Daspit had exactly one torpedo left. He kept that last fish. He ordered Tenniser to surface and head for Pearl Harbor. He was bringing evidence back with him.

Evidence that American submarines were being sent to war with weapons that didn’t work. What Daspit didn’t know was that his failed attack would finally force the US Navy to admit what submarine crews had been screaming about for 21 months. The Mark1 14 torpedo was fundamentally broken.

And that broken weapon was killing American submariners while letting Japanese shipping sail unmolested across the Pacific. This wasn’t just a technical problem. It was a catastrophe that had already cost hundreds of American lives and thousands of Japanese ships that should have been on the ocean floor. But by the end of 1943, American submariners would fix every major defect in their torpedoes, often over the stubborn opposition of the very people who designed them.

And once they had working weapons, American submarines would strangle Japan’s economy so completely that Japanese military leaders would later testify the submarine campaign was the single greatest cause of their defeat. Meanwhile, Japanese submarines, despite being some of the most technically advanced in the world, would accomplish almost nothing. They had excellent submarines. They had working torpedoes.

But they made strategic choices so fundamentally wrong that their submarine force became irrelevant to the war’s outcome. The first American submarine skipper to notice something was catastrophically wrong with the Mark1 14 was Lieutenant Commander Tyrell Jacobs commanding USS Sargo. On December 24, 1941, 17 days after Pearl Harbor, Sargo fired eight torpedoes at Japanese merchant ships. Jacobs heard the torpedoes strike the hulls.

He heard the metallic clangs through Sargo’s sonar. No explosions. The ships sailed away undamaged. Jacobs filed a detailed report. He stated flatly that his torpedoes had hit the target but failed to detonate. The Bureau of Ordinance reviewed his report and concluded the problem was crew error. The torpedoes were fine. Jacobs must have made mistakes in the attack setup. This became the Bureau’s standard response for the next 18 months.

Submarine commanders reported torpedo failures. Bureau of Ordinance blamed the submarine commanders. Lieutenant Commander Richard Voge, commanding USS Sailfish, fired 14 torpedoes at Japanese merchant ships in January 1942. He watched through his periscope as torpedo after torpedo ran under the targets stern or keel without exploding.

He also reported his torpedoes were running too deep, at least 10 ft deeper than their set depth. Bureau of Ordinance responded that the torpedoes were running at correct depth. The problem must be improper attack geometry or poor fire control. Other submarine commanders reported similar problems.

Lieutenant Commander Lewis Parks, commanding USS Pompo, attacked a Japanese freighter in January 1942. He fired six torpedoes from perfect firing position. All six ran under the target. The freighter sailed away undamaged. Parks reported his torpedoes were running too deep. Bureau of Ordinance blamed his depth setting procedures.

Lieutenant Commander James Co, commanding USS Skipjack, attacked a Japanese aircraft carrier on Christmas Day 1941, less than 3 weeks after Pearl Harbor. He fired four torpedoes from close range. All four either missed or failed to explode. Co later wrote in his patrol report that Japanese anti-ubmarine measures were so ineffective that a submarine could practically pursue Japanese ships up the bay, yet his torpedoes wouldn’t sink them.

By March 1942, submarine skippers throughout the Pacific were filing similar reports. Torpedoes running too deep. Torpedoes hitting targets without exploding. Torpedoes exploding prematurely before reaching targets. The patterns were consistent across different submarines, different crews, different commanders. But Bureau of Ordinance maintained there was nothing wrong with the Mark1 14. The Bureau had designed the weapon. The Bureau had tested it. The Bureau said it worked. The man who would finally break this bureaucratic stonewalling was Rear Admiral Charles Lockwood. In May 1942, Lockwood took command of submarines in the Southwest Pacific based in Fremantle, Australia. He was 52 years old, a career submarine officer who’d been commanding submarines since World War I. His crews called him Uncle Charlie. He listened to his people.

And when his submarine commanders told him their torpedoes weren’t working, Lockwood believed them. Lockwood was different from many flag officers. He’d spent his entire career in submarines. He knew the boats. He knew the weapons. He knew what worked and what didn’t. More importantly, he trusted his submarine skippers.

When they reported torpedo failures, Lockwood didn’t assume they were making excuses for poor performance. He assumed they were telling the truth and he was determined to prove it. In June 1942, Lockwood did something that violated every protocol in the Navy’s chain of command.

Without permission from Bureau of Ordinance, without official authorization, he took a submarine off combat operations and used it to run his own torpedo tests. He didn’t ask for permission because he knew he’d be refused. He just did it. He fired torpedoes set to run at specific depths through submerged fishing nets at Frenchman Bay near Albany, Australia. Then he measured the holes the torpedoes left in the nets. The methodology was simple but conclusive.

If the torpedo was set to run at 10 ft and it left a hole in the net at 21 ft, the torpedo was running 11 ft too deep. The results were undeniable. The Mark1 14 was running an average of 11 ft deeper than its set depth, sometimes 15 ft deeper. Lockwood had the proof. He sent his test results to Bureau of Ordinance with a detailed report.

The Bureau reviewed the data and dismissed it. The tests must have been conducted improperly. The nets must have been set at wrong depths. The submarine must not have been properly trimmed. The torpedo depth setting mechanism must have been improperly calibrated. There was nothing wrong with the Mark1 14 torpedoes design.

The Bureau of Ordinance had designed it. The Bureau had tested it at Newport. The Bureau said it worked. Therefore, it worked. Any evidence to the contrary must be flawed. The problem was the depth control mechanisms pressure sensor.

When engineers increased the warhead weight during three and development, they never recalibrated the sensor. The heavier warhead made the torpedo ride deeper in the water. This wasn’t a minor error. An 11 ft depth error meant torpedoes set to hit a destroyer’s keel would pass completely under the destroyer without making contact. It meant torpedoes aimed at the water line of a merchant ship would run harmlessly underneath. The fix was straightforward once the problem was identified.

Recalibrate the depth setting mechanism to account for the heavier warhead. moved the pressure sensor to the torpedo’s midbody where water pressure readings were more accurate. By late 1942, the depth problem was solved. But submarine commanders kept reporting failures. Now that torpedoes were hitting targets instead of running under them, a different problem became obvious.

Torpedoes were hitting targets and not exploding. The Mark1 14 used a Mark 6 exploder mechanism. This exploder had two triggers. A magnetic influence trigger designed to detect a ship’s magnetic field and detonate the warhead beneath the keel and a contact trigger designed to detonate on direct impact with the hull. The magnetic trigger was supposed to be revolutionary technology.

Detonate beneath the keel, break the ship’s back, sink it with one torpedo instead of three or four, but the magnetic trigger was failing catastrophically. Lieutenant Commander John Scott, commanding USS Tunny, found himself in a perfect attack position on April 9th, 1943. Three Japanese aircraft carriers were in front of him.

Scott was only 880 yards away, close enough to see aircraft on the carrier decks through his periscope. He fired all 10 torpedoes, aiming carefully at all three targets. He heard seven explosions. For a moment, the crew thought they’d scored hits, but when Scott looked through the periscope, all three carriers were maintaining speed and course. None appeared damaged.

The explosions had been premature. Later, intelligence reported that all seven torpedoes had exploded prematurely. The magnetic trigger had detected the carrier’s magnetic fields at a distance and detonated the warheads before the torpedoes reached the hulls. Premature detonations did no damage to the targets.

They just warned the enemy that a submarine was nearby and gave away the submarine’s position. It was worse than missing. A miss was silent. A premature explosion told every destroyer in the area exactly where to hunt. The magnetic triggers problems were three-fold. First, Earth’s magnetic field varies by location. The bureau had tested the exploder in waters near Rhode Island.

Pacific magnetic fields were different, causing the trigger to activate too early or not at all. Second, the magnetic trigger was hyper sensitive. Minor variations in magnetic field strength would cause premature detonation. Third, the exploder mechanism had design flaws. Water leaked into the casing, corroding electrical connections. brush riggings that supplied power to the magnetic sensor were inadequate and failed under combat conditions.

Lockwood wanted to deactivate the magnetic trigger immediately, but he needed authorization from higher command. That authorization came from Admiral Chester Nimmits on June 24, 1943. All submarines under Pacific Fleet Command were ordered to deactivate the magnetic exploder and use only the contact trigger.

This finally solved the premature detonation problem, but it revealed the third major defect. The contact trigger was also broken. That’s when Lawrence Daspit encountered Tonan Maru number three on July 24, 1943. With the magnetic trigger deactivated, his torpedoes should have exploded on contact with the tanker’s hull.

They didn’t. Nine perfect hits, nine duds. Daspit brought Tinosa back to Pearl Harbor with one unexloded torpedo. He handed it over to the base torpedo shop for examination. Rear Admiral Charles Lockwood met Daspit at the submarine pier. Lockwood later wrote, “I expected a torrent of cuss words damning me, the Bureau of Ordinance, the Newport torpedo station, and the base torpedo shop. I couldn’t have blamed him.

19,000 ton tankers don’t grow on trees. I think Dan was so furious as to be practically speechless. Lockwood ordered immediate testing. The base torpedo shop at Pearl Harbor conducted experiments. They fired torpedoes at underwater cliffs off Cahula Island. They dropped dummy warhead torpedoes from cranes onto steel plates at different angles. The tests revealed the problem.

The contact triggers firing pin mechanism was poorly designed. The firing pin was too heavy. When a torpedo hit a target at 90° perpendicular to the hull, the sudden deceleration created forces exceeding 500gs. That deceleration bent the firing pin before it could strike the percussion cap. The pin jammed in its housing. The warhead didn’t detonate. The better the shot, the more likely it was to fail.

A glancing hit at an oblique angle might work because the deceleration forces were lower and spread over a longer impact time, but a perfect perpendicular hit, exactly what commanders were trained to achieve in the attack doctrine, would jam the firing pin and produce a dud. American submarine doctrine emphasized making perfect 90° shots from the beam. That doctrine guaranteed the highest possible dud rate.

The torpedo shop disassembled Daspit’s unexploded torpedo. They found the firing pin mechanism exactly as the tests predicted. The pin was bent. The housing was damaged. The mechanism had failed under impact forces. Admiral Lockwood authorized immediate field modifications. The base torpedo shop at Pearl Harbor designed a lighter, stronger firing pin.

They fabricated the new pins from aluminum salvaged from Japanese aircraft propellers that had been shot down. The irony was noted by everyone involved. By September 1943, all submarines leaving Pearl Harbor carried torpedoes with modified firing pins. By November 1943, all three major defects had been fixed. Depth control corrected. Magnetic trigger deactivated.

Contact trigger redesigned. For the first time since the war started, American submarines had reliable torpedoes. 21 months after Pearl Harbor. 21 months of sending submariners to war with weapons that didn’t work. 21 months of ships that should have been sunk sailing away untouched.

The man who drove these fixes was Lockwood. He fought Bureau of Ordinance every step of the way. He conducted unauthorized tests when the Bureau refused to test. He documented every torpedo failure meticulously. He collected patrol reports from dozens of submarine commanders describing torpedo malfunctions.

He compiled statistics showing that American submarines were firing 10 torpedoes for every confirmed sinking. That ratio should have been 3:1 at most. The torpedoes were the problem, not the submarine commanders. He gave his submarine commanders permission to modify their own torpedoes when official modifications were delayed.

Some submarines were deactivating magnetic exploders on their own initiative, violating regulations because they knew the exploders didn’t work. Lockwood covered for them. He didn’t court marshall anyone for unauthorized torpedo modifications. He protected his people from Bureau of Ordinance Retribution. In early 1943, Lockwood flew to Washington to confront bureau officials directly.

He walked into a conference room full of senior officers, many of whom had designed the Mark1 14 and didn’t want to admit it was flawed. Low presented his evidence, test results, patrol reports, statistics. He showed that the magnetic exploder was unreliable. He showed that submarines were getting hits without sinks. He demanded action.

The bureau officials were defensive. They suggested Lockwood’s submarine commanders weren’t maintaining the torpedoes properly. They suggested the magnetic exploders were being damaged by rough handling. They suggested everything except that their design might be flawed. Lockwood lost his temper.

He told them, “If the Bureau of Ordinance can’t provide us with torpedoes that will hit and explode, or with a gun larger than a peashooter, then for God’s sake, get the Bureau of Ships to design a boat hook with which we can rip the plates off a target’s side.” The conference room went silent.

Nobody talked to Bureau of Ordinance that way. But Lockwood didn’t care about protocol. He cared about his submariners. He was sending men to war with defective weapons. And the bureaucrats who designed those weapons were more concerned about covering their mistakes than fixing them. Lockwood made it clear he wasn’t leaving Washington until something was done.

He had Admiral Nimitz’s support. He had evidence and he wasn’t backing down. Lockwood also did something else that was critical. He relieved submarine commanders who weren’t aggressive enough. In the first year of the war, many American submarine skippers were cautious, following pre-war doctrine that emphasized avoiding risk.

They’d make one attack, fire torpedoes from long range, then withdraw whether they’d scored hits or not. This was textbook procedure from peaceime exercises, but it didn’t sink ships. Lockwood identified the aggressive commanders and promoted them. He gave them the best boats and the best assignments. Men like Dudley Morton, Richard Oka, Samuel Dy, Eugene Flucky.

These were the commanders who would make American submarines legendary. Morton in Wahoo developed the tactic of having his executive officer man the periscope during attacks while Morton coordinated the overall battle. This freed Morton to process information from sonar, radar, lookouts, and the periscope operator simultaneously.

He could make better tactical decisions because he wasn’t fixated on one input source. Other commanders copied the technique. Samuel Dy commanding USS Harder became famous for hunting destroyers instead of merchant ships. Destroyers were dangerous targets, fast and armed with depth charges. Most submarine commanders avoided them. Deed them deliberately. In May 1944, Harder sank three destroyers in 4 days.

In June, Harder sank two more destroyers in two days. Di proved that aggressive submarine tactics could neutralize the hunters who were supposed to be hunting submarines. Harder was eventually lost with all hands in August 1944, but Dei had demonstrated what aggressive leadership could accomplish.

Eugene Flucky, commanding USS Barb, took aggression to new levels. In January 1945, Barb penetrated Namuan Harbor in China, attacked a Japanese convoy at anchor, and withdrew under fire. In July 1945, Barb conducted the only ground combat operation by American submarine personnel in World War II, landing a demolition team on the Japanese coast to blow up a railroad.

Flucky finished the war with the Medal of Honor, four Navy crosses, and a reputation as one of the most audacious submarine commanders in naval history. These aggressive commanders proved that American submarines could dominate the Pacific if they had working weapons, and weren’t handicapped by overcautious doctrine.

Lockwood gave them the weapons, gave them the freedom to fight, and stepped back to let them win the war. Lieutenant Commander Dudley Morton took command of USS Wahoo on December 31, 1942. Before his first patrol as commanding officer, Morton made a speech to the crew. He declared Wahoo expendable. Any crew member who wanted to remain in Brisbane had 30 minutes to request a transfer.

There would be no negative marks against anyone who stayed behind. Not a single crew member accepted the offer. They all wanted to sail with Morton. Morton’s third patrol in January 19 43 became legendary. He took Wahoo into Weiwak Harbor on the north coast of New Guinea. There were no charts of the harbor.

One of the crew had bought a cheap atlas in Australia that showed Wiiwac as a small indentation on the coast. Using that atlas as a guide, Morton navigated Wahoo into enemy waters. He found a Japanese destroyer nested with several submarines. Morton fired three torpedoes at the destroyer from 1200 yd. All three missed or malfunctioned. The destroyer detected Wahoo and turned to attack. Morton could see it coming through the periscope. The destroyer was charging straight at him at high speed.

Any normal submarine commander would have gone deep and run. Morton waited. He let the destroyer close the range. When it was close enough that collision seemed inevitable, Morton fired another torpedo straight down the destroyer’s throat. The torpedo hit the destroyer amid ships and broke it in half.

The destroyer sank in minutes. 2 days later, Wahu encountered a five ship convoy north of New Guinea. Morton attacked in daylight on the surface, running a battle that lasted 14 hours. He sank the transport Buyo Maru carrying over a thousand Japanese troops. He sank the freigher Fuku Maru. He damaged other ships in the convoy.

Then he surfaced and destroyed lifeboats with deck gunfire to prevent survivors from reporting Wahu’s position. It was brutal aggressive warfare. Wahoo returned to Pearl Harbor on February 7, 1943. Morton had expended all 24 torpedoes in a 23-day patrol. Normal patrol length was 60 to 75 days. He’d accomplished more in 3 weeks than most submarines did in 2 months.

The Navy awarded him the Navy Cross. His example changed the submarine forces culture. Other commanders saw that aggressive tactics worked. Admiral Lockwood started promoting aggressive skippers and relieving cautious ones. The silent service stopped being silent. American submarines went on the offensive.

By the time the torpedoes were fixed in late 1943, American submarines had the weapons, the tactics, and the commanders to wage unrestricted submarine warfare. The results were devastating. In 1942, with broken torpedoes and cautious tactics, submarines sank 109 Japanese ships totaling 640,000 tons. It was a modest beginning, hampered by torpedo failures and commanders who were still learning how to fight.

Many submarine skippers were following pre-war doctrine that emphasized caution. They’d approach a target, fire torpedoes from long range, then withdraw immediately to avoid counterattack. This was safe but ineffective. Torpedoes fired from 3,000 yd had time to malfunction during their run. Targets had time to evade.

And if the torpedoes were running deep or failing to explode, long range shots masked the problems. In 1943, things changed. The depth problem was fixed. By summer, the magnetic exploder was deactivated by midyear. Aggressive commanders like Morton were showing what could be done. Submarines sank more than 1.5 million tons that year. That was more than double the previous year’s total. But torpedo problems still plagued the force.

The contact exploder wasn’t fixed until September. Many submarines were still using torpedoes with faulty firing pins. They were getting hits but not sinks. In 1944, everything came together. Torpedoes worked reliably. Commanders were aggressive. Tactics were refined. Submarines sank over 3 million tons that year, double the 1943 total.

American submarines were operating close to the Japanese home islands. They were penetrating the Sea of Japan. They were hunting in wolf packs. They were devastating Japanese shipping. By early 1945, Japan’s merchant marine was effectively destroyed. There weren’t enough targets left to attack.

Submarines were struggling to find ships to sink. American submarines sank 1314 Japanese merchant vessels totaling 5.3 million tons. That was 55% of all Japanese shipping losses during the war. Submarines also sank one battleship, eight aircraft carriers, 15 cruisers, and 42 destroyers. The economic impact was catastrophic for Japan.

The Japanese home islands had almost no natural resources. Japan imported 90% of its oil. It imported all of its rubber. It imported 88% of its iron ore. It imported vast quantities of food, everything needed for war production. Oil from the East Indies, rubber from Malaya, iron ore from China and Manuria, food from Korea and Taiwan had to be shipped by sea. The merchant marine was Japan’s economic lifeline.

American submarines cut that lifeline. By mid 1944, oil tankers were being sunk faster than Japan could replace them. Refineries shut down for lack of crude oil. Without fuel, aircraft sat grounded on airfields. Training flights stopped. Combat sorties decreased. Warships remained in port because there was no bunker fuel.

The super battleship Yamato spent most of 1944 tied to a pier because there wasn’t enough fuel oil to operate it. When Yamato finally sorted on its suicide mission to Okinawa in April 1945, it carried only enough fuel for a one-way trip. There wasn’t enough fuel in Japan for the return voyage. Industrial production collapsed. Factories needed raw materials.

Ships that should have been delivering iron, ore, coal, bork site, and copper were on the bottom of the Pacific. Production of aircraft dropped. Production of ships dropped. Production of ammunition dropped. The Japanese war economy was starving.

Not because of bombing, not because of combat losses, because American submarines had destroyed the merchant marine that kept the economy alive. Japan’s cabinet testified after the war that the loss of shipping was the greatest cause of their defeat, not the atomic bombs, not the island invasions, not the strategic bombing campaign, the destruction of their merchant marine.

and American submarines accomplished that destruction while representing less than 2% of the US Navy. But the cost was high. 52 American submarines were lost during the war. 3,56 submariners died. That was a 22% fatality rate, the highest percentage loss of any branch of the American military. One in five submariners who went to war didn’t come home.

For comparison, the overall US military fatality rate was about 3%. Submariners died at seven times that rate. The losses were distributed throughout the war. Some submarines disappeared without a trace, presumed lost to mines or depth charges with no survivors. Some were sunk in known battles, going down fighting. USS Grunian was possibly sunk by her own defective torpedo that circled back.

USS Tang was definitely sunk by one of her own torpedoes. USS Wahoo was hunted down and destroyed in La Peru’s Strait. Each loss meant between 60 and 80 men dead. The submariners knew the risks. They volunteered for submarine duty, knowing the fatality rates. They went on patrol knowing they might not return.

They kept fighting despite broken torpedoes, despite losses, despite the knowledge that their own weapons might kill them. and they won. They strangled Japan’s economy. They cut the supply lines that kept Japan’s war machine running. They produced results that shortened the war and saved hundreds of thousands of lives, both American and Japanese. The cost was terrible.

But the alternative, continuing the war without an effective submarine campaign, would have been far worse. Meanwhile, the Imperial Japanese Navy operated the most technically advanced submarine force in the world. Japan built submarines larger than anything America produced. The I400 class submarines displaced 6,500 tons submerged, carried three bomber aircraft in a watertight hanger, and had a range of 37,000 mi.

They could sail from Japan to the American West Coast, attack targets, and return without refueling. Japan built submarines capable of 23 knots surface speed, faster than any American boat. Japan built submarines, human torpedo submarines called kiton, supply submarines, reconnaissance submarines.

By 1945, Japan had built all 39 of the world’s diesel electric submarines with more than 10,000 horsepower. Japan had the technology. They had excellent boats. They had skilled crews. They had torpedoes that worked from day one. But they accomplished almost nothing. Japanese submarines sank two American aircraft carriers in 1942. I19 sank USS Wasp on September 15th.

The same salvo of torpedoes also hit the battleship USS North Carolina, tearing a 32- ft hole in her hull. I168 sank USS Yorktown on June 7th after the Battle of Midway. These were significant victories, but they were isolated successes, not part of a sustained campaign. Japanese submarines damaged the battleship North Carolina.

They sank the cruiser USS Indianapolis in 1945. Total Japanese submarine sinkings for the entire war. About 184 merchant ships of approximately 1 million gross registered tons. Compare that to German Ubot which sank 2,840 ships of 14.3 million tons. Or American submarines 1,314 ships of 5.3 million tons. or even British submarines, 493 ships of 1.

52 million tons. Japanese submarines had the capability to match or exceed those totals. They failed because of strategic choices that were fundamentally wrong. Japanese naval doctrine was built around the concept of a single decisive battle like the battle of Tsushima in 1905 where the Japanese fleet destroyed the Russian Baltic fleet in one engagement.

Japanese strategists believed any future war would be decided the same way. Lure the American fleet across the Pacific, a trit with submarines and air attacks during the approach, then destroy it in one massive surface battle with battleships and carriers. Japanese submarines existed to support that doctrine.

Their primary mission was to scout for American naval task forces, shadow them, attack warships, not to attack merchant shipping. This doctrine was tactically reasonable but strategically bankrupt. American naval forces were fast, maneuverable, and heavily defended. Attacking an American carrier task force meant penetrating a screen of destroyers with sonar and depth charges, evading combat air patrols with radar, then trying to hit carriers that could make 30 knots and had multiple escorts.

Even when Japanese submarines succeeded, the cost was high. The submarine had to get close, expose itself, and then escape. Many didn’t. Finding and attacking merchant shipping would have been far more effective. Merchant ships were slow, typically making 10 to 12 knots. They were lightly defended, often sailing without escort early in the war, and they were absolutely critical to Allied logistics.

Every merchant ship carried fuel, food, ammunition, equipment. Sinking merchant ships disrupted operations, delayed invasions, forced the Allies to divert resources to convoy protection. An all-out campaign against American supply lines across the Pacific would have stretched Allied defenses thin. The distances were enormous.

San Francisco to Pearl Harbor was 2,400 m. Pearl Harbor to Australia was 4,700 m. Pearl Harbor to the Philippines was 5,000 mi. Those supply lines were vulnerable. Japanese submarines with their long range and endurance were perfect for interdicting those routes. But Japanese naval leadership never made that shift.

They kept tasking submarines to hunt warships even as the strategic situation deteriorated. Worse, as Japan lost territory and isolated garrisons needed resupply, submarines were diverted to supply missions. By 1943, Japanese submarines were hauling food and ammunition to bypassed islands. Torpedoes were removed from torpedo tubes.

Weapons were offloaded to make room for cargo. External cargo containers were welded onto submarine hulls. Combat submarines became glorified freighters, carrying rice and bullets instead of hunting enemy ships. These supply runs were suicide missions. Submarines would surface near island beaches at night to unload cargo. They’d be vulnerable, wallowing on the surface, defenseless against air attack.

American aircraft and patrol boats hunted them relentlessly. The casualties were appalling. Dozens of submarines were lost hauling supplies that could have been delivered more efficiently by fast destroyers or speciallydesigned cargo vessels. But the army demanded submarine support.

The Navy acquiesced and combat submarines were wasted on missions they were never designed for. Experienced crews and irreplaceable boats were thrown away, delivering a few tons of rice to islands that would be captured anyway. These supply runs were suicide missions. Submarines would surface near island beaches to unload cargo.

They’d be vulnerable, wallowing on the surface, defenseless. American aircraft and patrol boats hunted them relentlessly. The casualties were appalling. Dozens of submarines were lost, hauling supplies that could have been delivered more efficiently by fast destroyers or speciallydesigned cargo submarines. But the army demanded submarine support.

The Navy acquiesced and combat submarines were wasted on missions they were never designed for. Captain Atsushi Oi, a staff officer with Japan’s Grand Escort Command, later wrote about Japanese anti-ubmarine warfare failures. He stated bluntly, “Japan failed in anti-ubmarine warfare largely because her navy disregarded the importance of the problem. The Japanese Navy had no unified command for protecting merchant shipping until November 1943.

By that time, the submarine war was already lost. Even after creating the Grand Escort Command, resources were inadequate. Japan built destroyers designed for fleet battles, fast and heavily armed. They never developed cheap, mass-roduced destroyer escorts suitable for convoy duty. Britain and America built hundreds of destroyer escorts specifically for anti-ubmarine work. Japan never made that investment.

Japanese anti-ubmarine doctrine was also deficient. Depth charges were set to detonate at shallow depths. A US Congressman Andrew May revealed this fact in 1943, and Japanese forces adjusted their settings deeper. But even with correct settings, Japanese depth charges weren’t effective enough.

Japanese destroyers lacked the sonar and radar capabilities of Allied escorts. They couldn’t detect submarines as reliably or prosecute contacts as effectively. Japanese naval aviation also failed to develop effective anti-ubmarine tactics. American patrol aircraft sank dozens of Japanese submarines. Japanese aircraft rarely sank American submarines.

There was a fundamental cultural problem. The Japanese Navy prioritized offense over defense. Battleships and carriers were prestigious. Escort duty was not. Anti-ubmarine warfare was seen as a defensive, unglamorous mission that didn’t advance careers. The best officers and the newest equipment went to the strike forces. Convoy protection got what was left.

This wasn’t unique to Japan. Britain had the same problem in World War I and early in World War II. But Britain learned, adapted, and created an effective convoy system. Japan never made that transition. By mid 1944, Japan’s shipping situation was catastrophic. Oil imports dropped from 1.8 million tons in 1943 to 300,000 tons in 1944.

Rice shipments from Korea and Taiwan fell by 70%. Iron ore shipments from China dropped to a trickle. Factories shut down. Civilians went hungry. The military couldn’t move troops or supplies. American submarines were strangling Japan to death. and Japanese submarines were accomplishing nothing to stop it.

There was one area where Japanese submarines did inflict significant casualties. When USS Indianapolis was torpedoed and sunk by I58 on July 30, 1945, 879 sailors died, most from shark attacks and exposure during the 4 days before rescue. Indianapolis had just delivered components for the atomic bomb to Tinian. The sinking was a tragedy.

But by that point in the war, one cruiser didn’t matter strategically. Japan was already defeated. The war ended two weeks later. Admiral Charles Lockwood retired from the Navy in 1947. He’d served 35 years, most of them in submarines. He wrote several books about submarine warfare, including Sincm All published in 1951. He advocated for his submariners, ensuring their accomplishments were recognized.

He died on June 6th, 1967 at age 77. He was buried at Golden Gate National Cemetery in California alongside admirals Chester Nimttz, Raymond Spruent, and Richmond Kelly Turner. Lawrence Daspit, who brought Tinosa home with one torpedo after the Tonan Maru fiasco, continued commanding submarines. He made four more war patrols, sinking multiple Japanese ships.

He survived the war, continued his naval career, and retired as a rear admiral in 1962. He died in 1998 at age 87. The torpedo he saved from the Tonan Maru attack was instrumental in proving the contact trigger defect. That single torpedo provided the evidence Lockwood needed to force Bureau of Ordinance to fix the problem.

Dudley Morton continued his aggressive tactics. He made four more patrols as Wahoos commander, sinking ships on every patrol. His fourth patrol in March 1943, conducted in the shallow waters of the Yellow Sea, was legendary. In 10 days, Wahoo sank seven ships and damaged an eighth.

Morton’s fifth patrol began in late April 1943 and was equally successful. He fired 10 torpedo attacks in 10 days, sinking multiple vessels despite continued torpedo malfunctions. Morton’s seventh patrol began on September 9th, 1943. Wahoo was ordered to transit into the Sea of Japan through La Peru Strait. The boat was never heard from again. Japanese records later revealed Wahu was attacked by anti-ubmarine aircraft on October 11th, 1943 in La Peru Strait.

All hands were lost. 80 officers and crew. Morton was postuously awarded the Navy Cross. Wahoo received six battle stars and a presidential unit citation. Morton finished the war with 19 ships sunk, approximately 55,000 tons. He was one of the top three submarine commanders of the war. Richard O’Ne executive officer under Morton on Wahoo went on to command USS Tang.

He sank 33 ships for 116,454 tons, the highest total of any American submarine commander. Tang was sunk by one of her own torpedoes that ran in a circle on her final patrol. Okaane survived, spent the rest of the war as a prisoner, and received the Medal of Honor after the war. He died in 1994 at age 83. The lessons from the submarine war are stark.

Technical excellence means nothing without correct strategic employment. Japanese submarines were better than American submarines in many ways. They were larger, faster, longer ranged, carried more torpedoes. They had working torpedoes from day one, but they attacked the wrong targets.

They were used for supply missions instead of combat. They were never employed in a coordinated campaign against merchant shipping. American submarines had broken torpedoes for 21 months. But once the torpedoes worked, American submarines had the correct strategy, aggressive commanders, and relentless focus on strangling Japan’s economy.

The results speak for themselves. American submarines sank 55% of Japanese shipping. Japanese submarines accomplished almost nothing of strategic value. The other lesson is institutional. Bureau of Ordinance refused to believe there was anything wrong with the Mark14 torpedo. They dismissed reports from submarine commanders. They blamed crews for torpedo failures. They resisted testing.

They delayed fixes. It took a commander like Lockwood who was willing to bypass the bureau, conduct unauthorized tests, and fight bureaucracy at every level to get the torpedoes fixed. If Lockwood had been less determined, if he’d accepted bureau assurances that everything was fine, American submariners would have continued fighting with defective weapons for the entire war. The casualty rates would have been even higher.

The strategic impact would have been negligible. Sometimes the greatest victories come from solving problems nobody wants to admit exist. That’s what happened in the Pacific submarine war. American submariners knew their torpedoes were broken. Lockwood believed them and fought to fix the problems. Once they had working weapons, nothing could stop them.

Meanwhile, Japanese submarines had everything they needed except the correct strategy. Technology and hardware don’t win wars. Strategy and determination win wars. If you found this story as compelling as we did, please take a moment to like this video. It helps us share more forgotten stories from the Second World War. Subscribe to stay connected with these untold histories. Each one matters.

Each one deserves to be remembered. We’d love to hear from you. Leave a comment below telling us where you’re watching from. Our community spans continents and connects people who understand that history’s lessons remain relevant today. Thank you for watching and thank you for keeping these stories alive.

News

CH2 German Submariners Were Astonished When Hedgehog Mortars Sank 270 U-Boats in 18 Months – The Key To This Is…

German Submariners Were Astonished When Hedgehog Mortars Sank 270 U-Boats in 18 Months – The Key To This Is… …

I Hid From My Family That I Had Won $120,000,000. But When I Bought A Fancy House, They Came…

I Hid From My Family That I Had Won $120,000,000. But When I Bought A Fancy House, They Came… …

At The Family Dinner, I Overheard The Family’s Plan To Embarrass Me At The New Year’s Party. So I…

At The Family Dinner, I Overheard The Family’s Plan To Embarrass Me At The New Year’s Party. So I… At…

My Parents Tried To Take My $4.7m Inheritance – But The Judge Said: “Wait… You’re…”

My Parents Tried To Take My $4.7m Inheritance – But The Judge Said: “Wait… You’re…” I didn’t expect the…

My Dad Shredded My Harvard Acceptance Letter. “Girls Don’t Need Degrees, They Need Husbands,” He Spat – I Didn’t Cry. I Made A Call

My Dad Shredded My Harvard Acceptance Letter. “Girls Don’t Need Degrees, They Need Husbands,” He Spat – I Didn’t Cry….

At 13, My Dad Beat Me And Threw Me Out Into A Raging Blizzard After Believing My Brother’s Lies. I Crashed At My Friend’s Place Until…

At 13, My Dad Beat Me And Threw Me Out Into A Raging Blizzard After Believing My Brother’s Lies. I…

End of content

No more pages to load