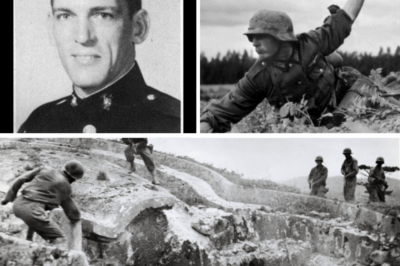

When The Germans Saw The American Jeep Roaming On D-Day – Their Reaction Showed How Doomed Germany Was…

June 7th, 1944, dawned gray and misted over the sands of Normandy, a morning that seemed both ordinary in its cold fog and monumental in its implications. Oberleutnant Klaus Miller of the 709th Infantry Division crouched behind a low rise of hedgerow, binoculars pressed to his eyes, and tried to make sense of the scene before him. The beach below, Utah Beach, had already been churned into chaos by the relentless waves and gunfire of the previous day. Bodies of soldiers lay half-buried in sand, barbed wire twisted into grotesque patterns, and the air still carried the metallic stench of artillery fire. Yet amidst the carnage, a quieter, more insidious shock unfolded—one that would haunt Miller and his men far more than the sound of shells ever could.

From his vantage point, Miller watched as a column of vehicles began to snake inland, moving with a precision that seemed almost unnatural. At first, it was a trickle, then a steady stream, and finally a rolling tide of metal and motion. Each vehicle glinted faintly through the fog, engines humming, tires crunching over sand and soil, every jeep as pristine and purposeful as if it had rolled straight off the assembly line that morning. He counted quickly, almost in disbelief, and by his reckoning, nearly 117 of them had passed before his eyes within just two hours. The scale, the regularity, the sheer order of it—all of it signaled that this was no ordinary assault, no haphazard landing like those the Wehrmacht had grown used to facing on the Western Front. This was something else entirely.

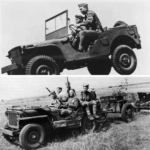

Miller had seen Americans before, yes, in skirmishes along the Western Front. He had endured their grenades, their small-unit tactics, and their stubborn willingness to fight to the last man. But those encounters had been different. Those Americans had moved on foot, exhausted and vulnerable, reliant on their own strength and courage to survive. What he saw now was not men marching into battle—it was the manifestation of an industrial nation’s power, every aspect of the American war machine brought to bear on the soil of France. These jeeps, these ¼-ton 4×4 command reconnaissance vehicles, were not merely transport; they were the embodiment of American logistics, ingenuity, and relentless production.

For Miller and the men of the 709th, the sight was almost terrifying in its implications. Each jeep was identical, sleek and purposeful, a small but perfectly designed machine. Each had markings, paint, and insignia that were meticulously standardized. Some bore the stamp of the Willys-Overland Motor Company in Toledo, Ohio, others came from Ford in Dearborn, Michigan. But to the German eye, what mattered less was the company of origin than the message each vehicle carried: the Americans could produce these in quantities Germany could barely comprehend. They could replace losses as easily as a rifle company could replace spent cartridges. What Germany faced was not just an army, but the industrial heartbeat of a nation, manifested in rolling, humming vehicles that carried men, weapons, and supplies with devastating efficiency.

The first wave of American troops had come ashore hours earlier, battered by surf, artillery, and flak. They had clawed a foothold out of chaos, and many had paid the ultimate price. But following them were not ragged, exhausted soldiers—they were machines, hundreds of them, arriving in unbroken order. LSTs, the Landing Ship Tanks, delivered their cargo with ruthless precision: thirty jeeps per ship, one convoy after another, vehicles flowing across the Channel with relentless regularity. From Miller’s perspective, the logic was undeniable. Each jeep, each truck, each piece of equipment was a testament to the sheer scale and consistency of American production. Where German forces had struggled to maintain a fraction of their vehicles at the front, the Americans had fleets at their disposal. The Cold calculation of American industry now moved on wheels, engines, and steel.

Hauptmann Vera Linderman, commander of the third company of the 919th Grenadier Regiment, had written in his after-action report on June 9th, 1944: “The enemy possesses vehicles in quantities we reserve for ammunition rounds. Every American unit down to the squad level appears to have motorized transport. We destroyed twelve of their reconnaissance cars yesterday. This morning, I count forty in the same sector. They treat complex military vehicles the way we treat rifle cartridges—as items to be used and discarded without thought.” The words were clinical, detached, yet the meaning behind them struck fear into those who read them. American military power, Linderman implied, was not simply in the bravery of its soldiers or the skill of its tacticians—it was in the factories, the endless production, the ability to pour material strength onto the battlefield with impunity.

Miller read the report again, letting the truth of it sink in. He imagined the American factories, running day and night, humming with machinery that could replicate these jeeps by the hundreds, perhaps by the thousands, every week. The scale was incomprehensible. He thought of his own supply lines, already stretched thin, already fraying under the weight of losses and miscommunication. And then he looked at the beach again, at the seemingly endless procession of vehicles, and understood that this landing was not just an operation—it was a declaration. The Americans were not merely invading Normandy; they were demonstrating the full weight of their industrial might, turning every factory, assembly line, and blueprint into a weapon as lethal as any artillery shell.

The significance of the moment was almost surreal. The German army, disciplined and experienced though it was, had long relied on careful calculations, defensive positions, and the assumption that attrition could slow or halt the advance of enemy forces. Here, in the fogged morning light of Utah Beach, those assumptions crumbled. The Americans had brought not just men, not just guns, not just artillery, but a network of production and transport so vast and precise that it rendered German predictions moot. The jeeps moved in perfect rhythm, each carrying men, radios, supplies—small, light, and fast. They were the connective tissue of a larger machine, invisible to the naked eye but devastating in function.

Miller realized, with a sinking feeling, that what he saw in those vehicles was more than hardware…

Continue below

June 7th, 1944, dawned gray and misted over the sands of Normandy, the kind of morning that seemed both ordinary and monumental at once. Oberator Klaus Miller, an officer of the 709th Infantry Division, crouched behind a low rise of hedgerow, binoculars pressed to his eyes, and tried to make sense of what he saw. The beach below, Utah Beach, had already been churned into chaos by the relentless waves and gunfire of the previous day, but now another, quieter kind of shock unfolded. A column of vehicles—dozens, then hundreds—poured inland in a river of metal, engines humming, tires crunching over sand and dirt, each one identical, each one fresh as if polished and painted that very morning. In just two hours, Miller counted 117 of them, and he knew in that instant that this was no ordinary assault.

He had faced Americans before, yes, in small skirmishes along the Western Front, but this—this was a force of a different scale entirely. These were not soldiers marching into death, vulnerable and exhausted, carrying all their burdens on their backs. These were machines, sleek and purposeful, rolling in like a tide. They were jeeps, the Americans called them: truck ¼-ton 4×4 command reconnaissance vehicles, each one a miracle of industrial design and simplicity. But to Miller and the men of the 709th, they represented something far more dangerous than the men who drove them. They were evidence that Germany was not merely fighting an army—they were fighting an entire industrial nation, a country capable of transforming the very act of war into a formula, a machine, a mass-produced certainty that defied all assumptions of battlefield logic.

The first wave had landed hours before, the initial troops battered by surf and artillery. But what had followed were not soldiers exhausted from the sea, but vehicles. LSTs, Landing Ship Tanks, had disgorged their cargo with relentless precision: thirty jeeps per ship, hundreds of ships arriving in endless convoys, rolling across the narrow waters of the English Channel. Each jeep was identical to the next—identical markings, identical engines, identical design. Some bore the label of Willis Overland Motor Company, Toledo, Ohio; others were stamped Ford Motor Company, Dearborn, Michigan. The Germans could see the cold logic of American production in every rivet and panel. This was an army shaped not just by training, not just by doctrine, but by factories. Factories that ran day and night, building machines to move, fight, and survive, in numbers that Germany could barely imagine.

Hauptman Vera Linderman, commander of the third company of the 919th Grenadier Regiment, wrote in his after-action report on June 9th, 1944: “The enemy possesses vehicles in quantities we reserve for ammunition rounds. Every American unit down to the squad level appears to have motorized transport. We destroyed twelve of their reconnaissance cars yesterday. This morning, I count forty in the same sector. They treat complex military vehicles the way we treat rifle cartridges—as items to be used and discarded without thought.”

Miller read the report again, feeling the truth of it sink in. The Americans had produced over 640,000 jeeps between 1941 and 1945. At peak, Willis Overland and Ford were completing a vehicle every ninety seconds on their assembly lines. For a single vehicle type to represent a quarter of all American military transport was a concept that made German planners’ heads spin. By contrast, Germany had struggled to produce barely 50,000 of their own light reconnaissance vehicles throughout the war. The numbers themselves were weaponized against them.

What was more bewildering to the German mind was the standardization. Every part of every jeep was interchangeable. A transmission from a destroyed Ford GPW could be bolted into a Willis MB in minutes. Engines, axles, spark plugs, even fan belts—they were all identical. This meant that the Americans didn’t repair vehicles in the German sense. They replaced parts—or the entire vehicle. Feld Valhanrika of the 716th Static Infantry Division wrote in his diary, observing a forward American unit: “The Americans do not repair their vehicles. They simply replace broken parts with new ones from an endless supply. I watched a damaged vehicle restored to operation in less than an hour. The engine was not repaired but lifted out completely and replaced as casually as changing a tire. Our mechanics would require a week for such an operation.”

The shock went deeper than logistics. German military culture had long emphasized careful maintenance, precise tracking of vehicles, and the preservation of each asset. Losing a vehicle through negligence could mean a court-martial. The German equivalent of a jeep, the Cabalva, required specialized mechanics, factory-level expertise, and weeks to repair if damaged. Yet here was the American method: simple, crude, and devastatingly effective. Each jeep’s life expectancy had been calculated at ninety days. If it was destroyed, it was not mourned, it was replaced. The replacement arrived within hours or days, delivered by the same endless convoys that had brought the first wave to Normandy.

Lieutenant Colonel Otto von Schroeder, chief of staff of the 352nd Infantry Division, captured the feeling in a letter to his wife: “The Americans fight a rich man’s war. They expend vehicles the way we expend ammunition. Yesterday, I saw a jeep strike a mine. The crew emerged unscathed, moved their gear into another vehicle that appeared within minutes, and continued their mission. The destroyed jeep was pushed aside and forgotten. In our army, such a loss would require reports, investigations, and weeks to obtain a replacement.”

By June 10th, twelve thousand vehicles had been landed in Normandy, jeeps comprising the largest single category. They reshaped the battlefield in ways German doctrine had not anticipated. Reconnaissance units moved with astonishing speed, artillery relocated as fast as forward observers could call them in, and supply units maintained continuous contact with the front. The Germans had expected pauses and consolidations, opportunities to counterattack, but those pauses never came.

The terrain of Normandy—the hedgerow country, the sunken roads, the embankments—was supposed to dictate the flow of battle, channeling vehicles into kill zones where machine guns and artillery could mow them down. Instead, the jeeps simply drove over embankments, through fields, and around obstacles. They created their own paths, forming an improvisational network of mobility that German planners could not map or anticipate. Ust Hans von Look, commander of a battle group in the 21st Panzer Division, later wrote: “The jeep gave every American unit the mobility we had only in our elite mechanized forces. One vehicle could carry a machine gun team, a mortar crew, communications equipment, or supplies. They appeared everywhere, in places we thought secure, calling in artillery, reinforcing positions, and striking behind our lines. We could not establish a continuous front because the Americans simply drove around us.”

This mobility was supported by logistics that approached the sublime in efficiency. American supply units had prepared for operations on an industrial scale: ships arriving daily carrying not just fuel and ammunition, but entire vehicles, spare engines, transmissions, and prepackaged component sets. Mobile workshops advanced behind the combat units, capable of any repair or replacement. If ten jeeps were destroyed in one engagement, ten replacements would arrive in forty-eight hours or less. Major Henrik Zimmerman of the 12th SS Panzer Division observed: “The American supply system operates like a factory production line extended to the battlefield. Everything is standardized, packaged, and delivered on schedule. They have removed the friction from warfare that Clausewitz described. While we struggle to maintain existing equipment, they simply order replacements as if from a catalog.”

The psychological impact on German soldiers was immediate and profound. Men who had been taught that Americans were soft, dependent, and materialistic now faced a reality that defied imagination. Endless columns of gleaming, identical vehicles, each fully equipped, rolled past units carefully preserving machinery from campaigns years before. Gret Wulf Gang Brown, a mechanic in the 21st Panzer Division, examined captured jeeps and marveled: “Every component is designed for mass production and easy replacement. The engine is simple but adequate. The transmission is robust rather than refined. Nothing is polished, nothing precisely fitted, yet everything functions reliably. They have sacrificed elegance for quantity, and quantity is winning the war.”

Even social constructs ingrained in N@zi ideology were challenged. African-American soldiers drove, maintained, and supervised motor pools with the same efficiency as their white counterparts. Felval Kurt Vagnner, a German observer, noted: “Negro soldiers operate and repair these vehicles with the same efficiency as white soldiers. Our racial theories suggest this should be impossible. Yet the evidence is undeniable.”

In the first days, American ingenuity and flexibility became apparent. Units welded additional armor, installed wire-cutters to deal with German piano-wire traps, mounted multiple machine guns, and adapted jeeps for specialized roles. Medical units converted them into ambulances with stretcher racks. Engineers attached mine detectors. Every modification was crude by German standards but effective immediately. Where German vehicles demanded special fuel, trained mechanics, and meticulous maintenance, American jeeps needed only gasoline, basic care, and initiative.

By June 15th, German intelligence estimated 4,000 jeeps were in Normandy, hundreds more arriving daily. To officers remembering the German invasion of Poland, which had fewer than 3,000 motor vehicles of all types, the scale seemed impossible. Calculations suggested that even if the Americans lost half their vehicles, they would remain more mobile than a full-strength German division. Colonel Ernst Vagnner reported to Field Marshal Rommel: “We face an enemy who has industrialized warfare to a degree we never imagined possible. They mass-produce military vehicles like civilian automobiles. Every soldier knows how to drive and perform basic maintenance. Their society is mobilized for mechanical warfare in a way ours never achieved.”

The contrast could not have been starker. German vehicles like the Cabalva were carefully constructed, well-engineered, and designed for longevity, but production was slow, numbering only a few dozen per day at peak output. American jeeps were simple, crude, but produced in numbers Germany could not match even with all its factories combined. Where Germany sought perfection, America sought adequate function multiplied by overwhelming quantity. Generalmajor Fritz Bioline summarized the situation succinctly: “We are artisans fighting an assembly line, and the assembly line is winning.”

By mid-June 1944, the American presence in Normandy was no longer a simple question of soldiers on the ground—it had become a logistical and operational phenomenon, one that the German military was ill-equipped to comprehend or counter. Each day brought more vehicles, more supplies, and more evidence that the United States had turned industrial might into a weapon of unprecedented power. For the German soldiers stationed along the hedgerow country, the jeeps had ceased to be mere transport vehicles. They were symbols of an unstoppable force, an unrelenting rhythm of war driven by production lines thousands of miles away.

Major Wilhelm Vontobin, observing the American breakout preparations near Saint-Lô, recorded his disbelief in a report to headquarters: “They have achieved something we thought impossible. The complete motorization of an army. Every soldier can be moved by vehicle. Every gun can be towed at highway speeds. Every supply item can be delivered directly to the consumer. We are fighting a nineteenth-century war against a twentieth-century enemy.” The Americans were redefining what it meant to fight, moving away from static defense and attritional strategies toward rapid, fluid operations made possible by mass-produced, standardized vehicles.

Reconnaissance units were at the forefront of this revolution. Where German doctrine relied on elite mechanized formations and horse-drawn infantry to probe enemy lines, the Americans used jeeps to send squads and platoons far ahead of the main force. A single jeep could carry a machine gun team or a mortar crew, allowing small American units to penetrate German positions quickly, gather intelligence, and report back without waiting for larger formations to mobilize. German commanders found these incursions maddening: the same hedgerows that had once provided cover now became corridors for American vehicles moving with astonishing speed.

The tactical flexibility of the jeep was magnified by its four-wheel drive, low weight, and simple design. Roads, embankments, and fields that had been natural obstacles for German vehicles were no match for these machines. Hedge rows meant to channel attackers into kill zones were simply driven around, over, or through. A pattern emerged: the Germans would fortify a sector, anticipating a frontal assault, only to discover that American jeeps had already bypassed them, calling in artillery or linking up with other units miles beyond their positions. The Normandy countryside, with its sunken roads, thick hedgerows, and hidden gullies, had been carefully studied and prepared for defense—but American ingenuity and mobility rendered these preparations almost irrelevant.

The psychological toll on German troops was immediate and severe. Soldiers who had grown up with a culture of careful maintenance, preservation, and resource scarcity were confronted by Americans who treated vehicles as disposable tools of war. Leutnant Friedrich Hoffman wrote to his family: “The Americans use their vehicles like we use bicycles for everything, without concern for wear. I saw a jeep delivering hot food to a single outpost, a trip that consumed fuel and engine life for the comfort of three men. In our army, those men would have walked and eaten cold rations. This wastefulness should be a weakness—but when you can waste without consequence, it becomes a form of strength.”

Beyond mobility, the supply system that supported these operations seemed almost preternatural. Every American convoy carried not just fuel and ammunition, but spare vehicles, engines, transmissions, and replacement parts in a pre-calculated, statistical array. Mobile workshops advanced alongside combat units, performing repairs that would have taken German mechanics days, sometimes weeks. If a vehicle was damaged beyond immediate repair, it was stripped for usable parts and abandoned. A replacement appeared almost immediately, delivered by the endless convoy system linking the beaches to the advancing front.

Major Henrik Zimmerman of the 12th SS Panzer Division noted in disbelief: “The American supply system operates like a factory production line extended to the battlefield. Everything is standardized, packaged, and delivered on schedule. They have removed the friction from warfare that Clausewitz described. While we struggle to maintain our existing equipment, they simply order replacements as if from a catalog.”

The jeep’s adaptability further amplified its impact. Engineers mounted mine detectors on some, while medical units converted others into ambulances with stretcher racks. Signal units loaded them with radio equipment, enabling rapid communication that allowed artillery and infantry to coordinate in ways German commanders could not disrupt. The vehicles were crude compared to German standards—rough welding, simple armor, functional modifications—but the results were immediate and effective. American ingenuity allowed small units to act independently, creating a network of mobility that German doctrine had not anticipated.

Even the social organization of American motor pools challenged N@zi assumptions. African-American soldiers operated and maintained jeeps with the same skill as their white counterparts. Felval Kurt Vagnner, an observer from the German army, wrote: “Negro soldiers operate and repair these vehicles with the same efficiency as white soldiers. Our racial theories suggest this should be impossible. Yet the evidence is undeniable.” The Germans, indoctrinated for years in the belief that racial hierarchy correlated with military capability, could not reconcile what they were seeing on the battlefield.

Attempts to slow the Americans by targeting vehicles were largely futile. Bridges destroyed to impede supply lines were quickly replaced with portable bridging equipment, often carried by jeeps themselves. Mines in fields were circumvented as vehicles simply drove around, over embankments, or through adjacent farmland. German forces learned that each tactical success was immediately neutralized by the sheer abundance and mobility of American transport. A single jeep destroyed was not a loss—it was a temporary inconvenience. Columns of identical replacements appeared within hours.

The psychological effect extended to German officers as well. Colonel Ernst Vagnner, compiling reports for Field Marshal Rommel, noted the profound implications: “We face an enemy who has industrialized warfare to a degree we never imagined possible. They mass-produce military vehicles like civilian automobiles. Every soldier knows how to drive and perform basic maintenance. Their society is mobilized for mechanical warfare in a way ours never achieved.” The gap between German engineering and American production had become a chasm. Germany had perfected individual vehicles, engineering them for longevity and refinement, but production was slow, and replacements scarce. The Americans, by contrast, produced simpler vehicles in overwhelming numbers, achieving mobility on a scale Germany could not match.

By late June, American motorization had enabled a cascade of operational successes. Forward units advanced rapidly, reconnaissance vehicles bypassed strongpoints, and supply lines followed without interruption. Artillery units relocated at speeds previously thought impossible, while infantry received consistent resupply without the delays that German doctrine had predicted. The battlefield became fluid, almost continuous, with American units appearing in unexpected locations and exploiting gaps before German reserves could respond.

Observers recorded the effects in vivid detail. Major Wilhelm Vontobin, still struggling to reconcile German doctrine with reality, described the scope of American operations: “Every soldier can be moved by vehicle. Every gun can be towed at highway speeds. Every supply item can be delivered directly to the consumer. We are fighting a nineteenth-century war against a twentieth-century enemy.” The American emphasis on redundancy, simplicity, and mass production created a battlefield in which failure was temporary and disruption almost impossible.

As the days progressed into July, the disparity became undeniable. German forces could not compete with the speed, flexibility, and sheer abundance of American motorized units. Hedge rows, previously considered defensive strongpoints, became mere obstacles for vehicles designed to traverse any terrain. Artillery positions were rendered vulnerable as jeeps carrying reconnaissance teams and radio operators located them quickly and coordinated precise counterfire. Supply lines, once considered potential points of vulnerability, were continuously reinforced, ensuring uninterrupted combat operations.

Operation Cobra in late July highlighted the full scale of the disparity. By that time, American forces in Normandy had amassed over 15,000 vehicles, with jeeps comprising the single largest category. Even if the Americans lost half of these vehicles in combat, they would remain more mobile than any German division at full strength. The Germans, still clinging to doctrines based on careful maintenance, limited production, and static defense, found themselves outpaced at every turn.

This motorization revolution extended beyond the immediate battlefield. The Americans demonstrated that victory in modern warfare was as much about industrial capacity as it was about courage or tactical skill. German officers who survived the campaign would later reflect on these lessons, incorporating principles of standardization, mass production, and design simplicity into postwar industry. The Volkswagen Beetle, for example, emerged as a civilian manifestation of lessons painfully learned in Normandy: a vehicle simple, robust, and capable of mass production, inspired by the relentless efficiency of the American jeep.

The Germans had encountered not just a military opponent, but a civilization capable of converting its industrial society into a weapon of war. Every jeep rolling inland from Utah Beach, every engine replaced in the field, every supply convoy moving inexorably forward, was a physical manifestation of American industrial might. Soldiers who had trained for years, who had studied doctrine and history, could only watch as the battlefield itself was reshaped by the rhythm of assembly lines and the abundance of production.

For Klaus Miller and the men of the 709th Infantry Division, the reality became clear with each passing day: the American jeep was more than a vehicle. It was a herald of a new kind of warfare, one in which the factory had become as crucial as the battlefield, where mass production outpaced skill and courage, and where mobility and supply were transformed from logistical concerns into instruments of victory. The Americans were not merely fighting—they were industrializing war in real time, and the Germans, masters of careful engineering and precision, found themselves hopelessly behind.

As the summer of 1944 progressed, German forces in Normandy confronted a reality that was becoming increasingly impossible to ignore. The American jeep, once dismissed as a simple reconnaissance vehicle, had transformed into the central symbol of a new type of warfare—one driven not solely by tactics, bravery, or elite units, but by industrial capacity, standardization, and relentless mobility. For German soldiers, officers, and engineers, the presence of these vehicles revealed a fundamental truth: the battlefield had evolved into an extension of the factory floor.

By late July, during the buildup to Operation Cobra, German intelligence had compiled extensive estimates of American motorized strength. Over 15,000 vehicles had landed in Normandy, with jeeps forming the largest single category. Reports suggested that even if half of these vehicles were destroyed, the Americans would remain more mobile than any German division at full strength. This staggering redundancy left German commanders confounded. Every attempt to exploit tactical vulnerabilities—ambushes, roadblocks, mines—was met with an almost preordained failure, as replacement vehicles arrived within hours, often before the Germans could capitalize on a temporary success.

The psychological consequences on German forces were profound. Soldiers trained in an ethos of careful equipment preservation now faced an enemy whose approach was the polar opposite. Where German vehicles were meticulously maintained, repaired, and logged, American jeeps were replaced at will, their crews unburdened by the need for long-term preservation. Leutnant Friedrich Hoffman’s observation remained emblematic of this mindset: “We preserve every engine, every axle, every part, while they simply discard and replace. In our army, such losses are catastrophic. For them, they are routine.”

The speed and flexibility offered by American motorization changed the very character of engagements. Reconnaissance vehicles bypassed strongpoints, artillery units could reposition in minutes rather than hours, and infantry supply lines kept pace with rapidly advancing troops. Static defenses, the cornerstone of German strategy in the bocage, proved ineffective. Fields, hedgerows, and sunken roads—previously reliable obstacles—were now mere terrain features to be traversed, not impediments. American forces operated with a tempo that German doctrine could not anticipate, let alone counter.

One of the most striking examples of this shift was the role of jeeps in integrating support and combat operations. Field kitchens, medical evacuation, forward artillery observers, and communications units all relied on motorized transport. Vehicles that would have once been reserved for elite mechanized divisions were now ubiquitous, transforming every squad and platoon into a self-sufficient, mobile entity. German observers recorded, often with incredulity, the extent of this adaptation. Major Henrik Zimmerman of the 12th SS Panzer Division wrote: “We are witnessing the removal of friction from warfare itself. Every supply, every repair, every movement appears calculated, standardized, and inevitable. The Americans fight not with men, but with an industrial system extended onto the battlefield.”

Even beyond tactical innovation, the jeep became a cultural shock for German troops. The egalitarian structure of American motor pools—integrating African-American soldiers in driving, maintenance, and supervision roles—clashed with N@zi ideology and deeply unsettled observers indoctrinated in notions of racial hierarchy. Feldwebel Kurt Vagnner remarked: “Our theories suggest such efficiency should be impossible, yet these soldiers operate with equal skill and discipline. We are forced to acknowledge the success of a system we have been taught to despise.” The practical consequences of this integration—rapid maintenance, constant mobility, and operational redundancy—were inescapable, regardless of ideological objections.

The jeep’s adaptability also reflected a broader American philosophy of functional pragmatism over refinement. Units welded additional armor, installed wire cutters, mounted multiple machine guns, and repurposed vehicles for medical, communication, and engineering tasks. German military culture, steeped in engineering excellence and precision, struggled to comprehend this improvisational yet effective approach. While German vehicles required specialized mechanics, exact fuel types, and careful attention to maintenance, American jeeps operated under a doctrine of sufficiency: simple, standardized, and easily replaceable. The contrast underscored a profound disparity in military philosophy.

German officers began documenting these lessons not merely as field reports, but as reflections on the nature of modern warfare itself. Colonel Ernst Vagnner’s reports to Field Marshal Rommel emphasized the structural mismatch: “We perfect individual vehicles while they perfect the system that produces vehicles. We train specialist mechanics while they design vehicles any soldier can maintain. We are artisans fighting an assembly line, and the assembly line is winning.” The language of defeat was not yet admitted, but the analysis was clear: American industrial capacity had become a decisive factor, eclipsing skill, experience, or valor.

Operational outcomes reinforced this insight. During breakout operations, American forces used jeeps to outflank positions, deliver intelligence, and coordinate firepower across vast distances. Road networks were improvised, moving columns avoided expected kill zones, and supply units followed without pause. German counterattacks were neutralized by the speed at which replacements arrived, vehicles were repaired, or units relocated. Even when tactical victories were achieved, they were often rendered meaningless within hours by the Americans’ relentless logistical machine.

By the end of July, it became evident to German commanders that the Normandy campaign was no longer simply a question of fighting skill. It was a confrontation between fundamentally different models of warfare. Germany’s system, built on precision, careful resource management, and long-term maintenance, was ill-equipped to match an opponent whose philosophy was quantity over perfection, speed over longevity, and redundancy over meticulous preservation.

The impact of American motorization extended beyond immediate military consequences. Officers who survived the campaign would later carry these lessons into postwar industrial and engineering development. The Volkswagen Beetle, emerging from the ruins of the Cubalva project, embodied many of the principles observed in Normandy: mass production, standardization, and simplicity. In essence, the Germans had witnessed an industrial revolution applied directly to warfare, and its influence would shape the future of both military and civilian engineering in Germany.

Reflections from former prisoners of war corroborated these conclusions. Felvable Otto Schultz, held in America for three years, later recalled: “We learned that modern war was not about courage or skill, but about industrial capacity. The Americans showed us that victory belonged to whoever could produce the most, ship the fastest, and replace losses immediately. The Jeep was not just a vehicle, but a symbol of a new kind of warfare we were not prepared to fight.” The jeep became a lens through which German soldiers—and, later, historians—could understand the transformation of military conflict in the 20th century.

For soldiers like Oberator Klaus Miller, the lessons were immediate and visceral. Each day brought more evidence of the Americans’ industrial advantage: new jeeps arriving where destroyed ones had been left, artillery relocating faster than expected, supply lines operating with clockwork precision. The battlefield itself seemed to move with the pace of American production, and German defensive doctrines struggled to keep up. In his diary, Miller noted the profound sense of disorientation: “We thought we were soldiers. They showed us we were simply workers in a factory of destruction.”

The physical presence of the jeep, in its endless numbers, became a symbol of what German observers called the “arsenal of democracy.” It was proof that industrial might could be projected across oceans and transformed into tactical advantage. Each vehicle, identical to the last, replaced without hesitation, demonstrated that the Americans were waging war not merely with men and skill, but with the full weight of a nation’s productive capacity. For German soldiers trained in scarcity, careful preservation, and meticulous engineering, this was both incomprehensible and demoralizing.

Even after the conclusion of the Normandy campaign, the lessons endured. German military planners and industrial engineers took note of the advantages conferred by standardization, mass production, and system-wide redundancy. They realized that future conflicts would be determined not solely by tactical genius or battlefield courage, but by the ability to organize, produce, and sustain material on an industrial scale. The jeep, simple in design but revolutionary in impact, had become an object lesson in the mechanization and industrialization of war.

By the time American forces moved beyond Normandy, the symbolic and operational lessons of the jeep were etched into German memory. Hedman Erns Bergman, who had observed operations throughout the campaign and would later become an automotive engineer, summarized the lesson succinctly: “The Americans taught us that in modern war, the factory is more important than the battlefield. Their jeeps arriving in endless numbers, each one identical and replaceable, showed us that warfare had become a branch of industry. We thought we were soldiers. They showed us we were simply workers in a factory of destruction.”

The story of German troops confronting American motorization in Normandy thus represents a turning point in the history of warfare. It was more than a mismatch of numbers or strategy; it was a collision between two fundamentally different approaches to war. Germany’s reliance on engineering precision and careful maintenance met the relentless, standardized, mass-produced mobility of the Americans. In the end, the endless columns of jeeps were more than vehicles—they were symbols of industrial power, a harbinger of modern warfare, and a lesson in how production could become as decisive as any weapon on the battlefield.

The Normandy campaign had shown, in stark relief, that the future of war belonged to those who could combine mobility, logistics, and industrial capacity. For German soldiers, officers, and engineers, the lessons of the jeep would shape both their understanding of defeat and the principles of rebuilding in a postwar world. It was not merely a story of a vehicle or a battle; it was a story of transformation, demonstrating that modern conflict was inseparable from industrial power and the ability to produce, replace, and sustain on a scale previously unimaginable.

News

CH2 What Eisenhower Told His Staff When Patton Reached Bastogne First Gave Everyone A Chill

What Eisenhower Told His Staff When Patton Reached Bastogne First Gave Everyone A Chill In the bitter heart of…

CH2 The “Ghost” Shell That Passed Through Tiger Armor Like Paper — German Commanders Were Baffled

The “Ghost” Shell That Passed Through Tiger Armor Like Paper — German Commanders Were Baffled The morning fog hung…

CH2 When 64 Japanese Planes Attacked One P-40 — This Pilot’s Solution Left Everyone Speechless

When 64 Japanese Planes Attacked One P-40 — This Pilot’s Solution Left Everyone Speechless At 9:27 a.m. on December…

CH2 Why One Private Started Using “Wrong” Grenades — And Cleared 20 Japanese Bunkers in One Day

Why One Private Started Using “Wrong” Grenades — And Cleared 20 Japanese Bunkers in One Day May 18th, 1944,…

CH2 How One Metallurgist’s “FORBIDDEN” Alloy Made Iowa Battleship Armor Stop 2,700-Pound AP Shells

How One Metallurgist’s “FORBIDDEN” Alloy Made Iowa Battleship Armor Stop 2,700-Pound AP Shells November 14th, 1942, Philadelphia Navy Yard,…

My Parents Chose My Sister Over Me, Like Always – Until the Letter I Left Made Her Scream In Anger And Disbelief…

My Parents Chose My Sister Over Me, Like Always – Until the Letter I Left Made Her Scream In Anger…

End of content

No more pages to load