When Germany’s Greatest Ace Returned to Base—And Found the Luftwaffe ERASED from the Skies in a Single Week

The sky over northern Germany in January 1945 was gray, lifeless, and cold—like a dying machine running on fumes. Major Erich “Bubi” Hartmann, the most lethal fighter pilot the world had ever known, eased his Messerschmitt Bf 109 G-10 through the winter haze and pointed her nose toward home. His fuel gauge trembled near empty. Beneath him, the frozen fields of Mecklenburg stretched endlessly, cut by rivers of ice and war.

He had flown hundreds of missions over these same skies, through years when Germany ruled the air and when they no longer did. But never had the air felt this heavy—so empty of life, so full of ghosts.

As his base at Parchim came into view, Hartmann radioed his approach, but the static swallowed his call. There was no answer. No hum of engines, no chatter from the ground crew. Just silence.

The once-proud Luftwaffe airfield lay spread before him, its snow-covered revetments like open graves. Only a handful of aircraft remained, their dark silhouettes scattered across the frozen runway. He throttled back and brought his Messerschmitt down, its wheels biting into the frost. The landing was smooth, practiced. His hands still obeyed instinct, even when his mind refused to believe what he saw.

As he taxied past the hangars, Hartmann noticed faces—mechanics standing in silence, their breath rising in the cold. No one waved. No one smiled. The war had drained even the gestures of habit from them.

He cut the engine, climbed out, and adjusted his leather gloves. The smell of oil and cordite clung to his uniform. He walked toward the operations hut, expecting the usual sound of telephones, typewriters, voices shouting coordinates. Instead, he opened the door to stillness.

Colonel Kessler, the base commander, stood at the wall, staring at the operations board. The white numbers, once filled with sortie counts and flight schedules, were nearly blank.

“Where is everyone?” Hartmann asked.

Kessler didn’t turn around. His voice was tired, almost detached.

“They’re gone, Erich.”

“Gone?”

Kessler pointed at the board with a pencil that trembled in his hand.

“Five thousand aircraft. In seven days. Destroyed.”

Hartmann blinked, as if he hadn’t heard correctly. “Five thousand?”

“Yes. Not damaged. Not grounded. Destroyed. And with them, five thousand pilots. Some of the best we ever had.”

He stepped closer to the wall. It was covered in pins and markers—bases, unit positions, and fuel routes. Half of them had been crossed out in red.

Kessler sighed. “The Ardennes Offensive is finished. Operation Bodenplatte—our last attempt at air superiority—failed before it began. We threw everything we had into the sky, and the Americans burned it all.”

Hartmann said nothing. He simply stared at the map. He had been in the air almost every day since Christmas, covering the Bulge where German tanks pushed into Belgium under Hitler’s final gamble. He’d seen P-51 Mustangs fill the clouds like silver daggers, faster and deadlier than anything Germany could field. He had watched the sky become a slaughterhouse.

But five thousand?

Continue below

The colonel reached for a folder on the desk, thick with papers and reports marked Geheim—Secret. “Here,” he said, handing it to Hartmann. “These came in from the General Staff this morning. Production figures from the Reich Air Ministry. Even if every factory runs at full capacity—which they won’t—we can’t replace what we’ve lost before spring. And by then…”

He trailed off, his voice cracking.

Hartmann flipped through the pages. The numbers told a story colder than the January wind. Bf 109s—output reduced by 40%. Fw 190s—shortages of aluminum. Jet production suspended. Fuel allocations cut by half.

“What about the new Messerschmitt 262s?” he asked quietly.

Kessler gave a dry laugh. “Grounded. We have engines, but no kerosene. And even if we did, no trained pilots left to fly them.”

Hartmann set the folder down. For years he had believed, despite the defeats, that Germany’s skill and discipline could still outmatch Allied numbers. Now the illusion was gone.

He walked outside into the freezing air. His crew chief, Weber, stood near the wreck of a fuel truck, its tanks empty. The man looked up, face pale beneath the grime.

“They called from Berlin,” Weber said softly. “The refineries are gone. Leuna, Pölitz, Blechhammer—all bombed flat. We’re down to synthetic fuel rations. Enough for one sortie a day, maybe two if we’re lucky.”

Hartmann nodded. He already knew the answer, but he asked anyway. “And replacements?”

Weber’s jaw clenched. “None. They said production’s been cut again. What we have now is all we’ll ever get.”

He gestured to the airfield—empty hangars, snow drifting through open doors, the skeletal remains of planes stripped for parts.

For the first time in his life, Erich Hartmann, the man called The Black Devil by Russian pilots, felt something close to fear. Not for himself. For what the silence meant.

He turned toward the horizon. The sound of Allied bombers echoed faintly from the west, distant thunder over the dying Reich.

He whispered to himself, “We’ve lost the sky.”

The next morning, January 16th, Hartmann woke before dawn. The barracks were quiet except for the wind clawing at the windows. He poured cold coffee into a tin cup and stared at the frost creeping up the glass. Outside, a handful of mechanics struggled to warm engines that hadn’t started in days.

A sergeant entered carrying the morning dispatches. He looked uneasy, as if delivering bad news had become routine.

“New orders, Herr Major,” he said, handing him a thin envelope.

Hartmann opened it and read. It was brief—one paragraph stamped Oberkommando der Luftwaffe.

“Effective immediately, Parchim Air Base is to operate at minimal readiness. Aircraft to be preserved for defensive operations only. Fuel to be conserved. All unnecessary flights suspended.”

He exhaled slowly, folding the paper. It was the official confirmation of what everyone already knew: the Luftwaffe was dying—not from bullets, but from starvation.

He stepped outside, the cold biting through his uniform. Overhead, the morning sky was pale blue, cloudless, beautiful—and completely empty.

He could remember a time when it had been full of sound: engines roaring, propellers slicing the air, squadrons climbing into the dawn. The Luftwaffe had once ruled these skies. Now they belonged to the enemy.

At the far end of the runway, Hartmann’s Bf 109 sat half-buried in frost, her yellow nose glinting weakly in the light. He ran a gloved hand along the fuselage, feeling the rough edges where patches covered bullet holes. The aircraft was tired, like its pilot. But she was all that was left.

“Start her up,” he told Weber quietly. “We’ll fly one last patrol.”

Weber hesitated. “There’s barely enough fuel for twenty minutes.”

“Then twenty minutes will do.”

The mechanic nodded and began cranking the starter. The Daimler-Benz engine coughed, sputtered, then came alive in a growl that echoed across the empty base. Hartmann climbed into the cockpit, the metal freezing against his hands. He could see his breath fogging the canopy.

He eased the throttle forward. The aircraft shuddered, rolled forward, and lifted from the ground.

As the base fell away beneath him, he looked out at the landscape below—fields dusted with snow, villages smoking from distant artillery, rivers frozen solid. Somewhere far beyond the horizon, American bombers were forming up for another day’s raid.

He climbed higher, the sun breaking through the clouds, flooding the cockpit with pale light.

For a moment, he could almost pretend it was 1940 again—when the Luftwaffe still ruled the air, when Germany still believed it could win. But the illusion shattered as he glanced at his radar screen: empty. No contacts. No friends.

He was alone in a sky that once belonged to him.

And deep down, he knew what awaited him when he returned to Parchim—that the world he had fought for, the one built on discipline, precision, and mastery of the air, had already vanished beneath the weight of 5,000 burning wrecks scattered across Europe.

The Luftwaffe wasn’t dying.

It was already dead.

January 17th, 1945.

The cold that morning cut through the air like glass. Frost clung to the inside of the cockpit windows, and the world outside seemed frozen in both time and defeat. Major Erich Hartmann, now twenty-two years old and the most successful fighter pilot in history, sat inside the mess hall of Parchim Air Base, staring into a bowl of soup that had already gone cold. Around him, a handful of surviving pilots sat in silence, not out of respect, but exhaustion.

They weren’t eating. They weren’t talking. They were waiting—for orders that never came, for fuel that never arrived, for hope that had long since frozen somewhere out over the Ardennes.

The door opened suddenly, letting in a gust of bitter wind and a young courier in a Luftwaffe greatcoat. His boots were crusted with snow. He looked barely old enough to shave. “Herr Major Hartmann,” he said, saluting sharply. His voice trembled. “Message from Berlin. High priority.”

Hartmann took the envelope and opened it with the precision of habit. Inside were two orders. The first: Parchim Base to reduce all flight operations by seventy percent effective immediately. The second: Twenty-seven new pilots assigned from the Luftkriegsschule (Air War School) to report within forty-eight hours.

He stared at the paper, then handed it silently to his adjutant, Lieutenant Neumann. The man read it, frowned, and whispered, “They’re sending us cadets. From the school. That means…”

Hartmann finished the sentence for him. “That means there are no more pilots left.”

He pushed his untouched soup aside and stood, moving toward the narrow window that looked out across the airfield. The snow had stopped, and sunlight gleamed off the wings of a few grounded Bf 109s, their engines covered to protect them from the cold. Smoke rose faintly in the distance from a crashed aircraft, still smoldering days after its fall.

For the first time since the war began, Hartmann could feel the end—not as a rumor whispered in briefing rooms or a line on a map, but as a physical presence. It was in the way the men moved, slower now, careful, as if even walking too fast might break something fragile that still held the illusion of purpose together.

Two days later, the trucks arrived.

Hartmann watched from the edge of the runway as a column of Opel Blitz transports rolled through the gate, their sides caked in ice and mud. From the back stepped the replacements—twenty-seven boys in brand-new uniforms, their faces pale and expressionless. They looked at Hartmann as if he were a legend come to life.

The youngest couldn’t have been more than eighteen. A few smiled nervously. Most just stared.

“Welcome to Parchim,” Hartmann said. His voice was calm, even gentle. “This is a front-line base. You’ll be flying combat immediately. Training will be short. The Americans and the Russians don’t wait for us to be ready.”

One of them, a tall, thin boy with clear blue eyes, raised his hand. “Sir, are the stories true? That you’ve shot down over three hundred aircraft?”

Hartmann gave a small, tired smile. “Three hundred and fifty-two.”

The boy’s eyes widened. “How do you survive that long, Herr Major?”

Hartmann looked at him for a long moment before answering. “You stop thinking about surviving.”

He turned away before the boy could respond.

That afternoon, Hartmann took two of the new pilots—Friedrich and Keller—on a training flight. The wind was sharp, and the temperature hovered well below freezing. The snow had turned to crusted ice, and the engines coughed reluctantly to life.

They climbed into the gray sky, their aircraft shimmering in the pale light. Hartmann led the formation, his Bf 109 moving with effortless precision, while the two young men wobbled behind him, struggling to maintain spacing.

He spoke into his radio, his tone patient but firm.

“Stay on my wing. Don’t chase shadows. Keep your speed. If you lose sight of me, climb—not dive. Always climb.”

“Jawohl, Herr Major,” came Friedrich’s nervous voice.

For thirty minutes, Hartmann guided them through maneuvers—loops, rolls, formation turns. Then, over the radio, came the voice of the ground controller, urgent and strained.

“Enemy aircraft approaching from the west. Repeat, enemy aircraft sighted at high altitude. Estimated twenty P-51s.”

Hartmann immediately scanned the horizon. A flash of silver glinted against the blue—Mustangs, slicing through the air like blades.

“Stay behind me!” Hartmann ordered. “Do not engage unless I say so.”

The boys obeyed, at first. But combat is chaos, and fear has its own gravity. When the first tracers streaked past, Keller broke formation, diving instinctively. The move was fatal. Within seconds, a Mustang fell in behind him, its .50-caliber guns chattering. Hartmann saw the fire bloom from Keller’s fuselage before the radio filled with static.

“Friedrich, pull up! Climb, damn it, climb!”

The young pilot yanked his Messerschmitt upward, but too late. The sky above them erupted in a storm of tracers. Hartmann pulled hard into a turn, caught the attacking Mustang in his sights, and squeezed the trigger. His cannon fired once—short, sharp. The American fighter disintegrated, its wings spinning away into vapor.

But Friedrich was gone.

When Hartmann landed, Weber was waiting at the end of the runway. One look at his face told the story.

“Both of them?” Weber asked.

Hartmann nodded silently. He climbed down from the cockpit, took off his gloves, and stared at his hands. They were trembling. Not from cold, but from anger—the kind that comes when you realize the men you’re fighting beside are no longer soldiers, but sacrifices.

He looked up at the pale horizon where the contrails of American planes still hung like scars across the sky.

“How long can this go on?” Weber asked quietly.

Hartmann’s voice was low. “Until there’s no one left to fly.”

That night, in the barracks, he sat at his desk writing in his logbook. His entries had once been neat and methodical—date, time, location, kills. Now, they had become shorter. Simpler. Colder.

January 19th, 1945. Two pilots lost. No contact with command. Fuel rations reduced again. Base strength: twelve aircraft operational.

He closed the book and stared at the candlelight flickering across the page. Outside, the wind moaned through the trees. In the distance, artillery rumbled—faint, constant, like thunder. The front was getting closer.

He leaned back, eyes heavy, and for a brief moment, let his mind wander to a world beyond the war—a world where the skies weren’t filled with smoke, where the sound of engines didn’t mean death. He thought of the boy Friedrich, and how eager he had been, how certain that skill and courage were enough.

Hartmann had believed the same once. But now he knew better.

Wars weren’t lost in the air. They were lost in the factories, in the fuel refineries, in the boardrooms where men made promises that engines could no longer keep.

The next morning, when he woke, frost had crept across the inside of the windows again, tracing veins like cracks in glass. He wiped them clear and looked out at the runway.

It was empty.

No sound of engines warming up. No chatter from the mechanics. No birds, no wind. Just silence and the distant smoke of a country burning itself to ashes.

And for the first time since the war began, Major Erich Hartmann—who had outflown, outshot, and outlived every enemy he had ever faced—felt something colder than fear.

He felt the end.

January 22nd, 1945.

Snow had buried the airfield overnight, softening the jagged edges of the revetments and covering the wrecked planes like white shrouds. The silence that morning was heavier than any bombardment. Even the mechanics worked slowly, their faces pale with exhaustion and cold, their movements mechanical—hands blackened with oil that never seemed to wash off anymore.

Major Erich Hartmann stepped out of the barracks and drew his greatcoat tight. His breath formed a ghost in the freezing air. The base felt like a tomb. Of the thirty-two aircraft once stationed at Parchim, only ten remained. Half of those were grounded for lack of spare parts.

At the edge of the runway stood a row of wooden crosses hammered into the frozen earth—hasty graves for the pilots who hadn’t come back. He recognized every name. He’d trained with them, fought beside them, watched them vanish into the clouds and never return.

Weber, his crew chief, approached, his boots crunching on the snow. “Herr Major,” he said quietly, “the new boys want to fly again. They’ve been asking for permission.”

Hartmann turned to face him, his blue eyes weary but sharp. “How many hours do they have?”

“Maybe sixty,” Weber said. “A few less. They’ve never flown under fire.”

Hartmann nodded slowly. “Then they’ll die in their first sortie. Like the others.”

Weber didn’t answer. They both knew it was true.

For a moment, neither spoke. The sound of the wind filled the silence between them. Then Weber asked, “And you, sir? Will you fly today?”

Hartmann looked out over the empty runway. “Yes,” he said finally. “Someone has to.”

He flew alone that morning. His Bf 109 G-10—the same aircraft that had carried him through hundreds of victories—still bore the black tulip painted across its nose, faded now but unmistakable. To the Allies, it had become a symbol of death. To Hartmann, it was something else: a reminder that he still existed, even when everything else around him was crumbling.

He climbed into the sky, the world falling away beneath him in shades of gray and white. At 12,000 feet, the clouds thinned, revealing the landscape below—a Germany he barely recognized. The forests he’d flown over for years were now scarred with bomb craters. Villages burned silently, their smoke rising like ink into the winter sky.

He spoke softly into the radio. “This is Black 1, on patrol. Altitude twelve thousand. Visibility clear. No contact.”

The reply came after a long pause. “Black 1, this is control. No orders. Maintain patrol until fuel warning. Over.”

He sighed. That was the new routine. Patrol empty skies, burn precious fuel, and return with nothing to report. The Americans didn’t even bother to send fighters this far east anymore. They didn’t have to. The Luftwaffe no longer had the strength to threaten them.

As he banked eastward, the horizon shimmered with a strange metallic glint. Hartmann squinted and adjusted his scope. Far in the distance—tiny silver specks, moving fast. Bombers. Dozens of them. B-17s, high and steady, heading toward Berlin.

And above them—Mustangs.

His heart quickened, not with excitement, but instinct. The rhythm of combat still lived in his veins. He throttled forward, climbing into the sun. The old reflexes took over—the calculations of speed, distance, altitude. He rolled inverted, dropped into a shallow dive, and picked his target.

He’d done this hundreds of times. He could almost feel the moment before the first shot connected.

Then his radio crackled.

“Black 1, break off! You have no support! Repeat, break off!”

Hartmann ignored it. He could already see the Mustang ahead of him, its silver wings catching the sunlight. The American pilot hadn’t seen him yet.

He closed the distance—two hundred meters, one hundred, fifty—then fired a short burst. His cannon tore through the Mustang’s fuselage. The enemy plane rolled, trailing smoke, and plunged downward, vanishing into cloud.

Hartmann didn’t watch it fall. He rolled out and dove for cover, diving so low his wingtips nearly brushed the treetops. Tracers sliced through the air behind him—two more Mustangs on his tail. He pulled hard left, the G-forces pressing him into the seat, the engine howling in protest.

He flipped the aircraft inverted, dropped a hundred meters, and snapped into a tight climbing spiral. The first Mustang overshot, the second broke off. Hartmann leveled out, his breath ragged.

It was over in less than thirty seconds.

He’d won again. But there was no thrill in it—only exhaustion. Every victory now felt like a delay, not a triumph. He was fighting not to win, but simply to keep breathing.

When he returned to base, the runway was nearly empty. Weber met him as he climbed out of the cockpit. “Another one?” he asked.

Hartmann nodded. “A Mustang. East of Magdeburg.”

Weber smiled faintly. “Three hundred fifty-three.”

Hartmann shook his head. “It doesn’t matter anymore.”

That night, the base command called an emergency meeting. The officers gathered in the dimly lit operations room, their faces gaunt in the candlelight. Colonel Kessler stood at the front, a single piece of paper in his hand.

“Gentlemen,” he said quietly, “effective immediately, Parchim Air Base is to be evacuated. Soviet ground forces have crossed the Oder River. Our defensive lines are collapsing. All personnel are to withdraw south toward Bavaria.”

Murmurs rippled through the room. Some refused to believe it. Others simply nodded, numb.

Hartmann asked, “What about the aircraft?”

“Those still operational are to fly out tomorrow. The rest will be destroyed.”

Hartmann looked around the room—at the tired, hollow faces of men who had once been the elite of Europe’s skies. There was no outrage, no argument, just silent acceptance.

When the meeting ended, he walked back out into the cold. Snow was falling again, soft and relentless. He stood by his plane for a long time, listening to the faint creak of the wind over the wings.

Weber approached, carrying a jerry can. “Orders are to burn the ones that can’t fly,” he said. His voice shook slightly.

Hartmann nodded. “I’ll help.”

They worked in silence. Together, they poured fuel over the wrecks—the broken, twisted remnants of aircraft that had once ruled the sky. Hartmann struck a match and tossed it into the puddle beneath a shattered Fw 190. The flames caught instantly, bright and hungry.

He watched as the fire spread from one plane to the next, consuming the ghosts of the Luftwaffe.

When the last aircraft burned, Hartmann turned to Weber. “Get some rest,” he said quietly. “We leave at dawn.”

Inside the barracks, he sat at his desk, staring at the half-empty logbook. He turned to a blank page and began to write, slowly, methodically, as he always had.

January 23rd, 1945. Parchim abandoned. Luftwaffe strength broken. Most pilots lost. The sky no longer belongs to us.

He stopped. His pen hovered over the page. Then he wrote one last line.

The war is not lost in the air. It is lost in the factories, in the hearts of men who no longer believe.

He closed the book and blew out the candle. The darkness settled around him like a heavy cloak.

Outside, the fires from the burning aircraft still glowed faintly against the snow. And above them, the sky—once filled with the roar of engines—was utterly silent.

For the first time in five years, Major Erich Hartmann could no longer hear the war.

But he knew it wasn’t over yet. The Soviets were coming. And the Luftwaffe’s last survivors would face them not in the air—but on the ground, surrounded, desperate, fighting a war that had already ended.

And he would fly again—because that was all he knew how to do.

January 25th, 1945.

The morning sky over Parchim Air Base glowed the color of steel. A gray so dense it swallowed the horizon. Snow drifted across the runway in thin white ribbons, covering the tracks of trucks that had already left in the night. The evacuation was nearly complete. Only ten men remained—mechanics, signal officers, and Major Erich Hartmann, their commander.

They had packed what little fuel was left into four jerry cans, strapped them to the fuselages of two Bf 109s, and loaded spare ammunition into the cockpits. Anything that couldn’t be flown south would be burned. Hartmann stood near the wing of his aircraft, gloves pulled tight, the wind stinging his face.

The airfield smelled of fuel and fire. Behind him, Weber and two mechanics worked silently, lighting torches under the wreckage of grounded fighters. One after another, the planes went up in smoke—orange flames twisting against the white sky.

“Are we the last ones?” Weber asked quietly.

Hartmann nodded. “Everyone else left last night. The Russians are less than sixty kilometers away. By sunset, they’ll be here.”

Weber looked toward the forest, where faint columns of smoke marked the direction of the front. “You think they’ll make it south?”

Hartmann didn’t answer. He adjusted his flight cap, slid the goggles over his forehead, and said only, “Let’s make sure we do.”

They shook hands—one soldier’s farewell to another—and then Hartmann climbed into the cockpit for what he knew might be his final flight.

The Daimler-Benz engine roared to life, echoing through the emptiness. The sound was haunting—once the proud music of the Luftwaffe, now a dirge for the dead. He taxied down the runway, the snow parting beneath his wheels, and lifted off into a sky that felt heavier with every second.

At 2,000 meters, he leveled off. The air was clear but painfully cold, the horizon lined with smoke. Below, the countryside of northern Germany sprawled in shades of gray and ash—burned towns, frozen rivers, and roads filled with refugees trudging through the snow. Families. Children. Soldiers without weapons. All of them heading west, away from the coming storm.

His radio crackled faintly. It was Colonel Kessler, broadcasting from another base farther south.

“Black 1, this is Eagle Nest. Do you read?”

“I read,” Hartmann replied.

“Confirm your departure. Soviet armor has crossed the Elbe. All northern units are ordered to fall back. Destroy remaining facilities. No equipment is to be left for the enemy.”

“Understood,” Hartmann said. “We’re en route. Two aircraft airborne.”

There was a long pause, then Kessler’s voice returned, softer now. “Godspeed, Erich.”

Hartmann said nothing. He simply looked down once more at Parchim—the base that had been his home for nearly two years. The hangars were burning now. Flames licked through the roof of the operations building, curling black smoke into the gray sky.

For a moment, the sight broke something inside him. Not anger. Not fear. Just the final, hollow understanding that the empire of the air was gone.

They flew south over the Elbe River, the water below choked with ice floes and debris. In the distance, Hartmann could see the contrails of Allied bombers heading east, glinting silver in the sunlight. None of them were attacked. There was no one left to attack them.

At midday, they passed over Leipzig, or what was left of it. The city was a blackened ruin. Streets twisted with wreckage, rail yards cratered, smoke rising from fires that had been burning for weeks. Hartmann could see bodies in the open squares—soldiers, civilians, horses—all frozen where they’d fallen.

He thought of Berlin. He thought of the orders that still came from there, insisting on victory, on faith, on miracles. But there were no miracles left.

Fuel gauges trembled. The needle in Hartmann’s cockpit sank toward empty. He tapped it once, knowing it wouldn’t change anything. “Weber, report fuel,” he called over the radio.

“Down to twenty liters, Herr Major.”

“Enough for one landing,” Hartmann said. “If we’re lucky.”

They pressed on, the landscape below shifting from flat plains to rolling hills. The sun dipped lower, staining the clouds blood red. It was beautiful, in a cruel way—the last sunset of a dying war.

They landed near Regensburg, at an improvised strip carved from frozen farmland. The base there was already overcrowded—jet units, remnants of bomber wings, and ground troops all jammed together, clinging to the illusion that southern Germany could still be held.

When Hartmann stepped from the cockpit, an officer approached, clipboard in hand. “Major Hartmann?”

“Yes.”

“You’re to report to Command immediately. Headquarters of Jagdgeschwader 52 has been moved to Neubiberg. They want a full account of your flights north.”

Hartmann followed him through the camp. Everywhere he looked, men were digging, hauling, building—trying to turn mud and snow into defenses. But their faces told the truth. They were beaten.

Inside the command tent, the air stank of smoke and sweat. Maps covered the tables—lines of red and blue ink that no longer meant anything. A major general stood at the far end, staring down at the chaos. He didn’t look up when Hartmann entered.

“You flew from Parchim?” the general asked.

“Yes, sir. Two aircraft. We burned the rest.”

“Good.” The general exhaled slowly, then turned. His eyes were sunken, bloodshot. “You’ve done more than anyone could have asked. The Reich owes you a debt.”

Hartmann almost laughed. A debt? To whom? To the dead boys he’d trained and buried? To the thousands of civilians burned alive in bombed cities? To a nation that had destroyed itself through arrogance and lies?

He saluted anyway. “Thank you, sir.”

The general nodded. “Get some rest. There will be missions tomorrow.”

Hartmann hesitated. “Missions?”

“Yes,” the general said simply. “Until the end.”

That night, Hartmann sat alone beside a small stove in the barracks. The wind outside moaned through the cracks in the walls. He pulled out his logbook and opened it to the last page.

He read over the names of the pilots who had flown with him—some alive, most not. He traced the numbers with his gloved finger. 352 victories. 1,400 sorties. Five years in the sky.

And for what?

He stared into the flames. In his mind, he saw the faces of the young boys who had come through Parchim—Friedrich, Keller, and so many others. Their voices echoed faintly, laughter from another lifetime.

He thought of the Americans, the Russians, the endless blue sky that had once seemed so full of purpose. And he realized something with a clarity sharper than fear: the sky no longer belonged to him. It belonged to whoever had the fuel, the factories, the men to fill it.

He was a hunter without prey, a warrior in a world that had outgrown him.

February 1945.

The Soviet armies crossed into eastern Germany. American bombers reached Munich and beyond. The last Luftwaffe squadrons fought like ghosts—appearing suddenly, striking, then vanishing forever.

Hartmann flew when he could. Each mission shorter than the last, each return to base emptier. By March, even the proud veterans of JG 52 had stopped counting kills. There was nothing left to count.

One morning, he found Weber in the hangar, staring at the horizon. “They say the Americans are a hundred kilometers away,” Weber murmured.

Hartmann nodded. “Good. Maybe they’ll end this faster than we can.”

When the final order came in May—cease all operations, surrender to Allied forces—Hartmann didn’t speak. He simply took one last look at his aircraft, the black tulip on its nose faded almost white. He placed a hand on the fuselage, feeling the cold metal beneath his palm.

Then he turned and walked away.

He would spend the next decade in Soviet prison camps. He would survive, as he always had. But the man who had once ruled the skies never flew again with the same joy.

Because in that winter of 1945, flying had ceased to be freedom. It had become a reminder of everything that could be lost, no matter how skilled, how brave, how devoted one man might be.

Erich Hartmann had learned the hardest truth a soldier can face—

That wars are not won by courage or talent alone.

They are won by the will and power of nations.

And when he left the airfield for the last time, snow falling gently around him, he looked back once at the silent runway and whispered to no one—

“The sky remembers us all. Even when no one else does.”

News

CH2 Japanese Zeros Were Said To Be Unstoppable – Until One American Pilot Accidentally Discovered This

Japanese Zeros Were Said To Be Unstoppable – Until One American Pilot Accidentally Discovered This Lieutenant Richard Bong’s P38….

CH2 THE DOCTOR WHO DEFIED H.I.T.L.E.R: The German Surgeon-Sniper Who TURNED His Rifle on the SS – And Became The Shadow On the Battle of the Bulge

THE DOCTOR WHO DEFIED H.I.T.L.E.R: The German Surgeon-Sniper Who TURNED His Rifle on the SS – And Became The Shadow…

CH2 Why One Squadron Started Painting “Fake Damage” — And Achieved Overwhelming Result In Just in One Month Against 40 Enemy Fighters

Why One Squadron Started Painting “Fake Damage” — And Achieved Overwhelming Result In Just in One Month Against 40 Enemy…

CH2 Japanese Troops Thought They Were A “Light” Force — Until They Wiped Out 779 of Them in One Night

Japanese Troops Thought They Were A “Light” Force — Until They Wiped Out 779 of Them in One Night At…

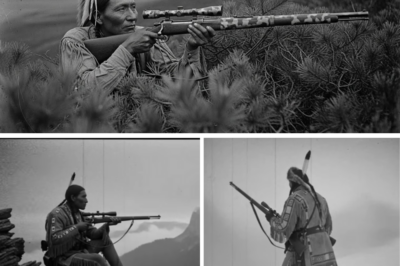

CH2 THE SHADOW WOLF: The Greatest Native Sniper to Ever Live in World War II – Yet His Name Almost Disappeared From History

THE SHADOW WOLF: The Greatest Native Sniper to Ever Live in World War II – Yet His Name Almost Disappeared…

CH2 Inside the Ford’s Willow Run Revelation — How Luftwaffe Officers POWs Stood Frozen as B-24s Rolled Out Every 63 Minutes, And Their Face Went Pale When They…

Inside the Ford’s Willow Run Revelation — How Luftwaffe Officers POWs Stood Frozen as B-24s Rolled Out Every 63 Minutes,…

End of content

No more pages to load