When German Engineers Tore Apart a Mosquito and Found the Glue Stronger Than Steel

The smell of wood and resin hung thick in the air, a strangely domestic scent invading the austere hangar outside Hamburg, where German engineers had gathered to examine the wreckage of the latest captured Mosquito bomber. The pale wooden panels gleamed under floodlights, looking absurdly like furniture lifted from a workshop rather than parts of an aircraft designed to humiliate the Luftwaffe. For two years, this “wooden wonder” had outrun and outmaneuvered every German interceptor thrown against it, but now, dissected on the concrete floor of a German airfield, it seemed almost laughably fragile. And yet, the engineers knew better. There was a subtle intelligence in every curve, every panel, that mocked their assumptions.

Dr. Carl Hines Hankle, a senior materials analyst at the Luftfahrtministerium, leaned closer to one of the panels, adjusting his spectacles as he tapped it with a knuckle. The sound was dull, resonant—not the metallic ring he expected from a machine of war. “It’s plywood,” he murmured, a tremor of disbelief in his voice. Around him, assistants whispered to each other, half incredulous, half amused. “A wooden bomber,” one muttered. “The English must have run out of aluminum.” But the laughter died quickly as the scope of the Mosquito’s design became clear. This wasn’t just a clever substitution of materials—it was a triumph of engineering, a defiance of every conventional rule of aircraft design the Luftwaffe had relied on for decades.

The smell of phenolic resin clung to the air, sweet and chemical, sharp and persistent. It coated the engineers’ clothes and filled their nostrils with a sense of otherworldly craft. As they began disassembling the plane, they cataloged each component meticulously. No rivets, no welding marks, no conventional fasteners—every seam, every joint was bonded with a substance that resisted the German tools meant to pry them apart. When Hankle attempted to separate two layers with a standard chisel, the blade snapped. “This is not carpenter’s glue,” he muttered. “Whatever they’ve used, it’s stronger than the wood itself.” His assistant offered a suggestion—perhaps a phenolic or bakelite-based resin—but Hankle shook his head. This was something else entirely: elastic, heat-resistant, almost alive in its resilience.

The team examined the fragments under magnification. Fibers from the birch and balsa core had fused seamlessly, forming a lattice that resembled living tissue more than man-made construction. Each curve of the fuselage had been crafted with a sculptor’s precision, reducing drag and channeling airflow while hiding structural strength beneath elegance. The Mosquito was a study in contradiction: fragile yet indestructible, domestic in appearance yet lethal in function, and astonishingly fast. The engineers, initially laughing at the notion of a wooden bomber, found themselves silent, almost reverent, as they measured, photographed, and documented every detail.

By midnight, the hangar floor was littered with sawdust, coffee cups, and sketches of wing profiles and fuselage contours. Hankle rubbed his temples, staring at the data on his clipboard, trying to reconcile the performance claims with the evidence before him. This plane, pieced together from plywood and glue, had achieved speeds that Germany’s finest metal bombers could not match. Somehow, the Mosquito had turned wood into armor and glue into steel. Hankle whispered to himself in disbelief, “How?” Outside, the city of Hamburg slumbered under the hum of distant night bombers, an empire’s dominance quietly eroding, while in the hangar, a quiet revolution in aeronautics had already taken root. The question no longer was whether the Mosquito worked—it was why, and what secret lay in its extraordinary glue.

The story began years earlier, in 1938, when the world was on the cusp of a mechanized war of steel. Jeffrey de Havilland, tall, composed, and stubbornly visionary, had appeared before the British Air Ministry with a set of blueprints that seemed almost sacrilegious. He proposed a bomber that flew faster than any metal aircraft, that carried no defensive guns, that could evade enemy fighters not with firepower but with speed and stealth—and that would be built almost entirely from wood. The room of officials listened politely, waiting for the punchline, and when none came, they rejected it outright. Wood was antiquated; speed alone was insufficient. Armor, guns, and metal were the future, they insisted. Yet de Havilland did not flinch. He saw what bureaucrats could not: the potential of a material overlooked, a philosophy of construction that emphasized simplicity, lightness, and precision.

Britain’s aluminum reserves were already under strain. Spitfires, Hurricanes, and Lancasters consumed every available sheet, and the nation’s aircraft production was stretched thin. De Havilland saw opportunity where others saw limitation. His company had spent years refining wooden aircraft construction for light planes and racing aircraft, cultivating a cadre of skilled woodworkers and cabinet makers who could shape, mold, and bond wood with exacting precision. Factories across Britain—furniture shops, piano workshops, cabinet makers’ studios—were already filled with men whose skills could now be redirected toward a warplane that relied on geometry, not mass, to survive.

De Havilland’s vision was audacious in every detail. He imagined a bomber devoid of turrets, its cockpit streamlined to a bullet-like silhouette, every panel and structural layer bonded rather than bolted, with balsa wood at its core to provide both lightness and resilience. The glue—his carefully guarded secret—was a resin so strong it seemed almost magical, able to hold the wooden components together against stress, heat, and vibration beyond anything the Luftwaffe had encountered. The Mosquito was to be a plane that relied on cunning and innovation rather than brute force, a flying contradiction of fragility and speed.

When these wooden bombers first took flight, the Germans scoffed. Reports filtered back to Berlin of “furniture planes” disrupting air raids, evading the Luftwaffe with ease. Yet when one Mosquito was forced down in a field near Hamburg and dragged to the hangar for examination, the ridicule turned to bewilderment. Panel by panel, joint by joint, the German engineers discovered that the plane’s secrets were encoded not in weapons or engines, but in its construction—its simplicity, its elegance, and above all, the mysterious adhesive that bound it together. The glue, a combination of synthetic resins and layered wood, resisted every chisel, knife, and crowbar applied by the Germans. It bent without breaking, absorbed shocks, and maintained structural integrity even under duress that would shatter steel.

As the night wore on, Hankle and his team began to grasp the magnitude of what they faced. This was not merely a wooden aircraft; it was a paradigm shift. Every assumption they held about materials, aerodynamics, and bomber design was being challenged by a machine that looked as though it had been lifted from a cabinetmaker’s shop rather than a factory floor. Its unarmed, fast, stealthy philosophy made traditional defensive calculations irrelevant. And in the quiet hours, surrounded by sawdust, broken tools, and the faint scent of phenolic resin, the German engineers realized something extraordinary: they were not just examining a plane—they were confronting an entirely new understanding of how an aircraft could be built, how strength could be derived from lightness, and how ingenuity could outpace brute force.

By dawn, Hamburg’s early light filtered weakly into the hangar, and the Mosquito lay in fragments, still resisting every attempt to submit it to conventional scrutiny. Hankle, exhausted, glanced at the notes, the photographs, the meticulous measurements. Somewhere within the wood, the glue, and the design, the Germans knew, lay a secret that defied replication, a principle that had allowed Britain to field a bomber capable of operating in ways their most advanced metal aircraft could not match. It was not simply engineering; it was philosophy, vision, and the foresight to leverage every tool, material, and skill at their disposal. The Mosquito had rewritten the rules of the sky.

And yet, for all their measurement, all their analysis, the greatest mystery remained unsolved. The glue itself—the lifeblood of the Mosquito’s resilience—remained impervious to every test the Luftwaffe could devise. What was it made of? How had the British engineered a substance stronger than steel yet flexible enough to survive the stresses of high-speed flight? Every experiment ended in failure. Every theory collapsed under the evidence of the intact fuselage and wings. Hankle could only stare at the disassembled bomber, its pale curves gleaming in the morning light, and wonder how the British had harnessed wood, glue, and human ingenuity to outpace the Reich’s most advanced aircraft. The Mosquito, in its quiet elegance, had become an unsolved puzzle, a lesson in innovation that would haunt the minds of those who tried to dissect it, a secret the Germans could neither steal nor replicate.

The story, as Hankle would later reflect in private diaries, was not simply about an airplane. It was about the audacity of thought, the courage to defy orthodoxy, and the brilliance of a designer who had looked at the limitations of his era and seen not obstacles, but opportunity. And as the sun rose over Hamburg, the Mosquito lay disassembled yet undefeated, a testament to a war fought not just with bombs and bullets, but with imagination, vision, and the unassuming strength of glue that proved stronger than steel.

Continue below

It smelled like furniture, not war. The German engineers gathered around the wreckage in a dim hanger outside Hamburgg, their white coats already stained with graphite and oil. A mosquito bomber captured almost intact after being forced down in a farmer’s field lay disassembled under flood lights.

Its pale wooden panels looked absurdly domestic, like something stolen from a carpentry shop rather than the sky. They had been told that this was the fastest bomber the British possessed, capable of outrunning Messids and Faka Wolves at full throttle. That claim seemed impossible to the Luftwaffa’s engineers would belong to the past to buy planes and museums, not to the era of jets and high octane fuel.

Dr. Carl Hines Hankle, a senior materials analyst from the Luftfart Ministerium, adjusted his spectacles and tapped one of the panels with a knuckle. The sound was not metallic, but dull and resonant like knocking on a coffin. “It’s plywood,” he murmured, disbelief, creeping into his voice.

Around him, technicians laughed quietly. “A wooden bomber,” one said. “The English must have run out of aluminum. They expected splinters and sawdust not a weapon that had humiliated their air defenses for nearly 2 years. Outside rain hissed against the hangar roof.

Inside the smell of phenolic resin filled the air sharp sweet and chemical, something between varnish and burned sugar. It clung to their clothes and throats as they worked. They began cataloging every component with the precision of surgeons. No rivets, no welds. Each panel had been bonded, not bolted. The seams were seamless, so smooth they reflected light like polished marble.

When Hankle tried to separate two layers with a chisel, the blade snapped. He frowned. This is not carpenters’s glue, he said. Whatever they used, it’s stronger than the wood itself. His assistant suggested it might be some kind of resin, perhaps belite. Hankle shook his head. Bely was brittle. This was elastic, heatresistant, almost alive.

He placed a fragment under a magnifying lens and saw fibers fused together like the grain of living tissue. What unsettled the most was the craftsmanship. Each curve of the fuselage had been molded with a sculptor’s precision. The British had built an airplane the way one builds a violin layer by layer, tone by tone. Every contour served a purpose, reducing drag, channeling air, hiding strength beneath elegance.

As the Germans measured, recorded, and photographed, something strange happened. The laughter faded. The more they touched the mosquito, the less they mocked it. They began to sense intelligence behind every joint, as if the craftsman who built it had anticipated their disbelief. By midnight, the floor was littered with sawdust sketches and coffee cups.

Hankle sat back, rubbing his temples, surrounded by fragments that refused to make sense. The numbers on his clipboard didn’t lie. This toy airplane had achieved speeds that their best metal bombers couldn’t match. Somehow Wood had defeated steel. He looked at the pale curve of a wing route under the light and whispered to himself, “How?” The irony nod at him.

Germany, the land of precision engineering, was being outpaced by a bomber glued together in furniture factories. Outside, the hum of night bombers echoed faintly over the city. the distant sound of an empire eroding. In that hanger, among the scent of glue and wet wood, something shifted. The question was no longer whether the mosquito worked, but why, and what secret hid within the glue that made it unstoppable.

In 1938, when the world was preparing for another mechanized war of steel, one man stood before the British Air Ministry with a proposal that seemed almost insulting. Jeffrey de Havland, tall, composed, and quietly stubborn, unfolded blueprints of a bomber that defied every doctrine of modern aviation.

It had no defensive guns, no armor plating, and most absurd of all, it was to be made almost entirely of wood. The room of officials listened politely, waiting for the joke. When none came, they rejected the idea outright. Metal was the future, they said. Wood belonged to the past. But De Havlin didn’t flinch. He understood something that bureaucrats could not measure in spreadsheets.

Speed was armor and simplicity was survival. At that time, Britain was already stretched thin. Aluminum, the lifeblood of aircraft production, was being consumed faster than it could be refined. Spitfires, hurricanes, and the new Lancasters demanded every sheet of metal the nation could produce.

Dohavlin looked at the arithmetic and saw not disaster but opportunity. His company had spent years perfecting wooden construction for light aircraft and racing planes. Britain’s countryside was filled with small workshops, furniture makers, piano builders, cabinet craftsmen, skilled men who could shape wood but had no place in the metal war.

What if he thought their hands could be turned toward building something faster, lighter, and quieter than anything on Earth? He envisioned a bomber without turrets or gun crews. Its twoman cockpit streamlined to a bullet’s silhouette. Instead of rivets, layers of birch plywood would be bonded with Ecuadorian balsa wood at the core materials chosen not for glamour, but for geometry.

birch for strength, balsa for lightness, the two joined by a glue stronger than any mechanical fastener. The technique known as laminated monoc construction had been used in furniture long before aircraft. But into Havlin’s mind, it became an equation of survival. Every ounce saved in armor could be spent on speed. If it could outrun enemy fighters, it wouldn’t need to fight them at all.

When the war began in 1939, his idea seemed to evaporate under the weight of reality. The Air Ministry ordered bombers with guns turrets and thick armor flying fortresses of metal that could trade blows. But war has a way of humbling certainty. By 1940, after the fall of France and the desperate days of the Blitz, Britain faced shortages so severe that even impossible ideas were reconsidered.

De Havland returned with a prototype design, insisting that his wooden bomber could be built in furniture factories without stealing a single sheet of aluminum from Spitfire Production. Reluctantly, they approved one prototype. In the autumn of 1940, under Grey Hartford skies, the first mosquito took shape. Piano builders from London sanded the wings. Violin makers crafted the curved nose.

The adhesive that bonded every seam came from furniture laboratories. phenyl formaldahhide resin, a synthetic glue that hardened into something close to amber. When applied between layers of wood and pressed under heat, it fused into a single material, neither wood nor plastic, but something in between light, resilient, and remarkably strong.

It was quite literally born from craftsmanship and chemistry. On November the 25th, 1940, the prototype painted training yellow rolled onto the runway at Hatfield. Jeffrey de Havlin Jr., the designer’s son, climbed into the cockpit. The engines roared twin Merlin tubistas, trembling like restrained animals.

As the aircraft lifted, the crowd expected struggle. Instead, it leapt forward as if weightless. Within seconds, it was climbing faster than any bomber they had ever seen. At altitude, its speed exceeded 390 mph, faster than the Spitfire MC 1, faster than any fighter then in service. The Air Ministry observers silent moments before now, whispered in disbelief.

A wooden plane had outflown the best machines of metal and myth. That night, De Havland walked alone through his workshop, past the half-finished frames, glowing under lamps. He placed his hand on one of the laminated panels, and felt the warmth from the curing glue. It was smooth, alive with promise. The world would never see war the same way again.

A bomber built from furniture wood had just proven that imagination could outrun fear. When the mosquito entered combat, it carried no guns, no gunners, and no illusions. Its survival depended entirely on mathematics. The first operational squadrons that received the aircraft in 1941 stared at it with quiet disbelief.

Pilots who had flown lumbering Blenhams and Wellingtons were now expected to fly a bomber that looked more like a racing plane, slim, graceful, and unprotected. The crew consisted of only two men, a pilot and a navigator seated shoulder-to-shoulder in a cockpit barely large enough for both. There was no rear gunner to cover their backs, no armor plate between them and the flack bursts waiting beyond the clouds.

The flight manual was brutally simple. If intercepted, do not fight run. Keep the throttle wide open and trust in the Merlin engines. The Air Ministry, once skeptical, had now become obsessed with the mosquito’s speed. Official tests at Bosam Down had clocked the aircraft at nearly 400 mph, faster than any operational fighter in the Luftwaffa’s inventory.

But numbers on a chart, and survival in enemy airspace were not the same thing. The Mosquito would have to prove that speed alone could replace armor. Its baptism came on September 20th, 1941 when a formation of mosquitoes from number 105 squadron took off from Swant and Mley for their first daylight bombing raid over Oslo. The mission objective was precise.

Hit the Gestapo headquarters and escape before enemy fighters could react. At 50 ft above the sea, the bombers stre toward Norway, their wooden wings slicing through spray and mist. Radar stations detected them too late. When the alarm reached Luftvafa command, the mosquitoes were already on their return course.

German fighters scrambled from Stavanger but never closed the gap. Witnesses on the ground reported a ghostly roar followed by silence as if the bombers had vanished into thin air. Every aircraft returned to base unscathed. The next test was far bolder.

In January 1943, a mosquito reconnaissance flight penetrated deep into Berlin airspace in broad daylight. The city’s sirens wailed for the first time in months, not because of a massive raid, but because of two unarmed bombers flying faster than the defending fighters. The Luftwaffa’s radar operators watched the blips on their screens accelerate beyond pursuit.

When the mosquitoes dropped their 500 lb bombs on the capital, Herman Guring himself was in conference. Furious, he shouted that the attack was a personal insult. He ordered interceptors to chase the intruders at all costs. None succeeded. By early 1943, mosquito crews had begun to understand the machine’s rhythm. At 2500 ft, it danced above flack bursts like a leaf on a storm. The laminated wood absorbed vibrations that would have cracked metal skins.

Even direct hits often failed to ignite fires. The absence of aluminum meant fewer sparks and less fuel vapor ignition. Pilots described it as flying a living thing, flexible, forgiving, responsive. One crew returning from a low-level raid over Cologne recounted how tracer fire chased them through the Rine Valley. The shells seemed to float beside us, then fall away.

It was as if the air itself was protecting us. The mosquito’s reputation spread quickly among both sides. British newspapers called it the wooden wonder. German pilots called it dertoel haltz the devil of wood. Its effect on morale was immediate. Luftvafa squadrons stationed in occupied Europe received new standing orders. If a mosquito is cighted, do not pursue unless conditions are perfect.

The aircraft could not be caught in level flight and in dives. It accelerated beyond structural safety limits for German planes. Each mission added new legends. In February 1943, mosquitoes from number 105 and 139 squadrons executed one of the most daring precision strikes of the war.

The daylight raid on Berlin scheduled to coincide with a speech by Goring himself. As his words echoed through the Reichto, the windows rattled with the shock of explosions. The timing was so perfect that German propaganda sensors couldn’t hide the humiliation. The unthinkable had happened. Wooden bombers had struck the heart of the Third Reich and escaped without loss. The success changed everything.

The Royal Air Force began redesigning operations around the Mosquito’s unique blend of speed and stealth. It became the preferred aircraft for photo reconnaissance, pathfinding, and surgical bombing. Every sorty proved a simple truth. The less you carried, the faster you flew. The faster you flew, the longer you lived.

The men who flew it started to believe in its legend. They called it the plane that forgot how to die. But across the channel inside the cold laboratories and workshops of the Luftwaf, disbelief turned into obsession. The German high command wanted to know how a plywood aircraft could humiliate their finest machines.

To them, it was not just a military failure. It was a scientific insult. Somewhere inside those smooth wooden panels was a secret the Reich had to uncover. In the spring of 1943, a British mosquito on a reconnaissance flight over northern Germany was caught in a storm of flack. The pilot managed to glide for miles before crash landing in a marsh near Hamburg.

Miraculously, the aircraft didn’t burn. When German troops reached the wreckage, they expected twisted metal and melted fragments. Instead, they found something that looked eerily like a broken boat. Smooth wooden panels light enough for a man to lift, still smelling faintly of resin and smoke. To the Luftwaffa’s technical branch, it was the find of the year. The order was immediate recover everything.

Even the smallest fragment was to be sent to a secret analysis hanger outside Reckalin the Luftwafa’s primary testing ground. Under harsh flood lights, the mosquito lay on wooden trestles like a patient on an operating table. Engineers circled it with clipboards and scalpels, their breath fogging in the cold.

They were men accustomed to steel and rivets to welding torches and precision gauges, not to sanding blocks and glue. The first cuts were hesitant, almost surgical. Each layer they peeled back revealed more questions than answers. The outer skin was birch veneer, only a few millime thick, but astonishingly uniform.

Beneath it was a honeycomb of balsa wood, light as air, yet remarkably stiff. Then came another layer of birch, all fused together, as if grown from a single tree. Dr. Carl Hines Hankle led the analysis. He was an expert in materials fatigue who had spent years studying the failures of metal airframes. Now he stood in silence staring at the seamless joints. “They’ve turned carpentry into engineering,” he muttered.

“His team measured densities, tensile, strength, and sheer resistance. Every test defied expectation. The laminated composite could bear almost twice the load of aluminum at half the weight. It resisted moisture, heat, and vibration. When one technician tried to separate two panels with a hydraulic press, the wood cracked, but the adhesive bond did not.

The Germans had used cine glue, a milk derived adhesive in their own wooden trainers and gliders. It was cheap and easy to make, but degraded in humidity and heat. This British glue behaved differently. It seemed impervious to everything. Hankle ordered chemical analysis. The laboratory reported a compound unknown in German aviation, a synthetic resin based on phenol and formaldahhide catalyzed under pressure. When heated, it didn’t soften.

It hardened further, turning into a thermoset polymer that bound wood fibers on a molecular level. It was in essence synthetic armor hidden inside wood. Hankle couldn’t hide his frustration. Germany’s chemical industry, once the envy of the world, had produced wonders like synthetic fuel and rubber. Yet, it had never developed this kind of adhesive. The reason was painfully simple resources.

Phenolic resins required phenol and methanol derived from colar, and both were being consumed by explosives production. Even if the Luftwaffa had known the formula, they couldn’t have made it in quantity. The discovery ignited a mixture of admiration and despair. The mosquito wasn’t just fast, it was practical genius. Every component told a story of adaptation.

The British had taken their shortages and turned them into innovation. The fuselage was shaped in two mirror halves molded over concrete forms in furniture factories. When glued together, they formed an airtight shell that required no internal bracing. The result was smoother, lighter, and stronger than any riveted construction.

One of Hankle’s assistants, a young engineer named Vogle, stared at the cross-section of a wing under magnification. “It looks alive,” he said quietly. “The glue lines formed patterns like the veins of a leaf.” “He was right. The structure flexed under stress instead of fracturing. It absorbed shock, dissipated energy, and returned to shape.

In a world obsessed with rigidity, the mosquito had been built to bend. When Hankle presented his findings to Luftwafa command, the room fell silent. He placed two samples on the table, one of aluminum, one of laminated birch bonded with the British resin. The wooden sample bent and snapped back. The aluminum one stayed deformed.

Gentlemen, he said, we have been building the wrong kind of strength. But pride dies hard. Some officers refused to believe that glue could win a war. Others demanded a German replica, a muka ornat, to prove the concept. Yet deep down, the engineers knew the truth. They could copy the shape, the dimensions, even the engines.

But they could not copy the soul of the mosquito, the glue that turned fragile wood into a weapon. As they packed their samples for Berlin, the smell of the British resin still hung in the hanger, sweet, sharp, unyielding. Hankle lingered a moment longer, running a gloved hand over the splintered wing. They built this in a furniture factory, he whispered.

“And we, with all our steel, cannot catch it.” “The order came from the top. If the British could build a wooden bomber that outpaced every German fighter, then Germany would build one faster, stronger, and deadlier. The project was given a name meant to mock its rival Muka the Nat, a tiny insect meant to sting the British mosquito.

On paper, it looked like a statement of pride, an attempt to prove that German engineering could master anything the Allies invented. In practice, it became a slow motion tragedy of overconfidence. The first prototypes were assigned to a small team at the Lufart Forchungenstalt in Bronvi. They began with captured mosquito drawings and the fragments Hankle’s team had meticulously cataloged. But from the beginning, the numbers betrayed them.

The British had used lightweight balsa imported from Ecuador, a wood Germany could no longer access due to Allied blockades. Their engineers substituted pine and beach, harder, heavier, more available. A single wing section that weighed 280 kg in the Mosquito ballooned to 410 in the Muka mockup. The glue 2 was a compromise. Without access to phenolic resin, the team reverted to cassine adhesive mixed with formulin to slow degradation.

It worked well enough in dry weather, but under heat and moisture, it began to soften a flaw that every engineer recognized, but none dared report. Still, the Reich’s propaganda machine demanded results. Hankle’s reports warning of adhesive instability were quietly rewritten before reaching Berlin. Production orders were issued to furniture factories in Dresden and Castle. Ironically, the very same kind of workshops the British had used successfully.

But German workers faced different conditions. Raw material shortages, constant air raids, and shortages of trained labor. The Mosquito had been born in creativity. The Muka was born in desperation. By late 1943, the first prototype stood complete. A sleek, pale imitation of the British aircraft. Under the flood lights, it looked convincing enough.

Twin engines, smooth fuselage, identical dimensions. But the illusion ended as soon as it left the ground. During its maiden flight, the test pilot Hman Ernst Kesler noted sluggish controls and unexpected vibration at high speed. At 350 mph, the wings began to resonate. The laminated layers groaned audibly. Within minutes, thin cracks spread along the leading edges.

He throttled back and landed hard, the undercarriage collapsing under the strain. When engineers examined the damage, they found the culprit moisture had seeped into the glue lines, weakening the joints. The adhesive had not failed outright, but it had softened just enough to alter the aerodynamic shape. In aviation, just enough was fatal.

The second prototype fared no better. Built with modified adhesives and extra bracing, it flew heavier and slower. On paper, it reached 360 mph faster than a Hankle. He 111, but still 50 mph, slower than the mosquito it was meant to catch. A third prototype broke apart entirely during a lowaltitude dive test.

The investigators tried to blame pilot error, but the truth was obvious. The wood had delaminated mid-flight, tearing the wing from the fuselage. By 1944, the Muka project was effectively dead. What remained were the reports, thick, meticulous documents filled with tables and graphs, but also something rare in German technical writing despair.

One memorandum from a senior engineer admitted that the design cannot achieve par with British construction due to fundamental material limitations. Another written in the margins of a test report read simply, “We are fighting physics with paperwork.

” Inside the Reich Ministry of Aviation, no one wanted to deliver the news to Herman Guring. His fury over the mosquito had already become legend. He had promised Hitler that the Luftwafa would reclaim the skies. Yet wooden bombers still flew unchallenged over Berlin, taunting them with each daylight raid. When he finally learned that the MUA had been cancelled, he smashed a glass ashtray against the wall and shouted, “We are defeated by carpenters.” For the engineers, the humiliation cut deeper than any reprimand.

Germany’s identity rested on precision metallurgy and control qualities the British had somehow turned upside down. The mosquito was not perfect. It was audacious. It broke rules that German engineering held sacred. never trust organic materials, never rely on manual craftsmanship, never tolerate variability. And yet it worked. Its wooden shell flexed where metal would crack absorbed vibrations, where rivets would fail.

Hankle, who had watched the entire fiasco unfold, wrote in his personal journal that autumn, “We are trapped by our own logic. We have machines without imagination, and they have imagination without machines.” He never sent that line to his superiors. It would have sounded like treason. But among his peers, the sentiment spread quietly, an acknowledgment that the British had won not through superior industry, but through the courage to defy their own textbooks.

As winter settled over the ruins of Germany’s cities, the surviving mosquitoes continued to appear above the clouds, sleek and silent. Their polished wood reflected moonlight like ghosts. Down below the men who had tried to imitate them stood in their workshops surrounded by warped wings, cracked fuselages, and the bitter smell of failed glue.

The Muka had proven the one lesson every engineer dreads copying. Genius is easy. Understanding it is impossible. By 1944, the Mosquito was no longer just an aircraft. It was a presence. It moved through the night skies of Europe like a rumor impossible to predict, impossible to stop.

The Luftvafa’s radar operators dreaded the faint blip that appeared and vanished too quickly to track. Interceptor pilots called it duratan Yagger, the shadow hunter. Even ground troops hearing its low wine at dawn learned to look up in fear, knowing that if a mosquito could reach them, no one was safe. The statistics told the story in numbers that defied belief. The average loss rate for heavy bombers like the Lancaster hovered around 5 to 7% per mission. For the Mosquito, it was less than one.

One aircraft lost for every 200 sorties. It meant that a mosquito crew, unlike their comrades in the slower armored bombers, could survive dozens of missions. Pilots began to joke grimly that flying a mosquito was safer than walking across Piccadilly after dark. But behind the humor lay something extraordinary.

An unarmed aircraft had become the most survivable machine in the Royal Air Force. Inside Germany, the disbelief turned into humiliation. Every intelligence report that crossed Herman Guring’s desk was another wound to his pride. He had once promised Hitler that the Luftwaffa would maintain absolute air superiority. Now British bombers made daily visits to Berlin. And the most infuriating of them all, the mosquito seemed to choose its timing for maximum insult.

In January 1943, it had dropped bombs on Berlin just as Guring began a radio address. In January 1944, it repeated the stunt during another high-profile meeting. Both times it escaped untouched. Guring reportedly shouted, “I turn green with envy when I see those wooden aircraft flying over Berlin. The British can afford to lose pilots, but they don’t lose them because they fly so fast that our fighters can’t catch them.” The truth was more painful. The Luftvafa had grown old while the mosquito stayed young. Germany’s best

pilots were dying faster than they could be replaced, and the new generation lacked the training to fight an enemy that refused to play by the rules. Conventional bombers could be intercepted, predicted, herded into kill zones. The mosquito ignored every script. It came in singles and pairs, flying at treetop level, then vanished into clouds. By the time radar picked it up, it was already gone.

At Reckland and Pinamunda, engineers tried to develop faster interceptors, new variants of the Faka Wolf 190, the high altitude Mi410, even the jetpowered Emmy 262. On paper, the jets could outrun the Mosquito. In practice, they could never be in the right place at the right time. Jet engines of the era needed long runways, perfect fuel, and gentle handling.

The mosquito needed only a patch of grass and two Merlin. For German civilians, the mosquito became a psychological weapon more powerful than any bomb. Its raids were precise railway stations, Gustapo offices, communication centers, but they carried symbolic weight far beyond their physical damage.

In Berlin, people whispered that the British had built a plane invisible to radar. In occupied Copenhagen and Oslo, the resistance celebrated each appearance as proof that the Allies could strike anywhere at any time. The mosquitoes roar became the sound of inevitability. The RAF understood this power and used it ruthlessly.

When heavy bombers pounded German cities at night, mosquitoes flew ahead to drop incendiaries and flares marking targets with pinpoint accuracy. When the bombers returned home, mosquitoes returned hours later to strike rescue crews and command posts. They seemed tireless, omnipresent, untouchable. Even when flying alone, a single mosquito could force the Luftwaffa to scramble entire squadrons of interceptors, burning precious fuel and exhausting pilots for nothing. The German high command responded with desperation, disguised as strategy.

New radar networks were built to track fast targets, and propaganda officers claimed that the mosquito was overrated, that its speed came at the cost of payload. But the numbers could not be hidden. In 1944 alone, mosquito bombers dropped over 1900 tons of explosives with fewer than 200 aircraft lost.

The figure was so efficient that one British officer quipped, “It’s not a bomber. It’s a surgical instrument.” By autumn, Guring’s rage had turned to superstition. He ordered his aids never to mention the aircraft by name during briefings, as if silence could erase it. Fighter command logs show a pattern of exhaustion, pilots claiming to chase phantoms that vanished into cloud.

Radar stations reported false echoes moving faster than their calibration limits. Ground crews swore they saw mosquitoes at altitudes no piston engine could reach. The myth had outgrown the machine. Dr. Hankle, the engineer who had once dissected the captured mosquito, watched it all unfold from his laboratory. He had stopped correcting his colleagues when they called the plane a ghost.

In his private notes, he wrote, “It is not the wood that terrifies us. It is the idea that something so light can carry such power.” By the final winter of the war, the mosquito’s very name could silence a room in Germany’s command centers. Reports of sightings came with a sigh rather than an alarm. Everyone knew that by the time the warning arrived, the damage was already done.

The Luftwaffa still flew, but its morale was hollowed out. For them, the mosquito was not an aircraft. It was inevitability, precision, and humiliation shaped into wings. When the war ended in 1945, the mosquito had already become legend. It had flown more than 80,000 combat sorties, photography, bombing, pathfinding, and nightfighting with losses so small that even the statistitians doubted their accuracy.

In the hangers of postwar Europe, its sleek wooden fuselage seemed an artifact from another world, something too elegant to have belonged to the chaos that created it. Germany lay in ruins at cities, scorched by the heavy bombers the mosquito had guided with uncanny precision.

And yet in the minds of the engineers who survived it, was not the Lancaster or the B7 they remembered with awe. It was the wooden ghost that had humiliated their science. At war’s end, Allied inspection teams invited captured German engineers to tour Havlin’s plant at Hatfield. Among them was Dr. Carl Hines Hankle, the same man who had once dissected a downed mosquito and declared its glue a miracle.

Now he stood in the assembly hall watching craftsmen in overalls polish the curved fuselage halves before they were bonded together. The smell of resin filled the air again. Sharp chemical unforgettable. He turned to his British escort, a young engineer barely out of university, and asked how many men had designed this process. The Britain smiled. Not many, but thousands built it.

That sentence stayed with him for years. In post-war report, Hankle wrote that the mosquito’s true secret was not chemistry or aerodynamics, but culture, a willingness to let craftsmen and scientists share the same space. Where Germany’s factories had been ruled by rigid hierarchy and fear of failure, the British had allowed improvisation.

A violin maker could teach an engineer about resonance. a chemist could learn from a furniture worker. Out of that collision of worlds had come something that no pure theory could have predicted. The lessons spread quickly. In the late 1940s, engineers on both sides of the Atlantic began experimenting with new laminated materials, fiberglass, resin composits, and later carbon fiber, all direct descendants of the mosquito’s wooden skin.

What had been born from scarcity became the foundation of abundance. Even the newly formed American aerospace industry studied De Havlin’s methods. Boeing engineers called the Mosquito the ancestor of every composite airframe we build today. In Britain, the aircraft’s legend grew quietly.

The Royal Air Force kept mosquitoes in service well into the 1950s, long after jets had taken over the skies. Pilots loved its agility, its silence, and its soul. One veteran said, “It felt like the airplane wanted to live as much as you did.” Museums displayed it as a masterpiece of wartime design, but those who had built it remembered something humbler.

The smell of sawdust, the rhythm of glue brushes the sound of piano craftsmen hammering spars together while London shook under the blitz. For De Havland himself, the success was vindication. His impossible idea had not only worked but changed the very meaning of engineering. He once told a journalist, “We were never trying to outmuscle the enemy. We were trying to outthink him.

” His words would echo through every generation of designers who followed. And for the Germans who had tried to imitate the mosquito, the aircraft became a mirror reflecting their own limits. The MUKA prototypes were melted down after the war. None survived. But in the archives of what became West Germany’s new aviation industry, Hankle’s notes endured.

The final line of his last wartime journal read, “They proved that imagination, when disciplined by necessity, is stronger than steel.” Time transformed the mosquito from a weapon into a lesson. It taught that progress sometimes comes not from abundance, but from desperation, not from metal and muscle, but from daring to see beauty in the ordinary. Out of plywood and glue had risen a machine that terrified an empire and redefined what was possible.

Today, historians still debate whether the Mosquito was the greatest aircraft of the Second World War. But the numbers speak for themselves. faster than any fighter of its era, lighter than any bomber, and deadlier to the enemy’s pride than to its troops.

When you walk past one in a museum, its surface still gleams like varnished oak. You can almost smell the resin, the ghost of that glue that once defied an empire. The men who built it are gone now, their names scattered across archives and airfields. Yet, their idea remains alive.

Every time a modern airliner takes off with composite wings or a spacecraft launches wrapped in resin and fiber. They proved that technology is not born from comfort but from courage. The courage to build what everyone else calls impossible. So the next time you see a mosquito’s photograph slender, smooth, and silent, remember what it represented. Not just British ingenuity, not just wartime necessity, but the moment when imagination outran fear.

If you believe that true strength lies in daring to dream beyond logic, comment #1 below. And if you think the world still underestimates the power of human creativity, leave a like and subscribe for more untold What we do stories that remind us why even wood and glue can change industry.

News

CH2 How An “Untrained Cook” Took Down 4 Japanese Planes In One Afternoon

How An “Untrained Cook” Took Down 4 Japanese Planes In One Afternoon December 7th, 1941. 7:15 a.m. The mess deck…

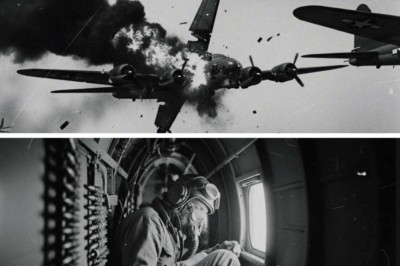

CH2 How One Gunner’s ‘ILLEGAL’ Sight Turned the B-17 Into a Killer Machine

How One Gunner’s ‘ILLEGAL’ Sight Turned the B-17 Into a Killer Machine October 14th, 1943. The sky above Germany…

CH2 Japan Pilots Couldn’t Believe The Black Sheep Squadron Commanded the Skies

Japan Pilots Couldn’t Believe The Black Sheep Squadron Commanded the Skies The morning air over the Solomon Islands carried…

CH2 Japan Never Expected B-25 Eight-Gun Noses To Saw Ships Apart

Japan Never Expected B-25 Eight-Gun Noses To Saw Ships Apart Bismarck Sea, March 3rd, 1943. At precisely 0600 hours,…

CH2 Japanese Admirals Never Knew Iowa’s 16 Inch Guns Could Hit From 23 Miles- Until They Had To Learn The Lesson Paid With 4 Of Their Ships

Japanese Admirals Never Knew Iowa’s 16 Inch Guns Could Hit From 23 Miles- Until They Had To Learn The Lesson…

CH2 What Eisenhower Told Staff When Patton Turned His Army 90 Degrees in 48 Hours Shocked The Entire Meeting

What Eisenhower Told Staff When Patton Turned His Army 90 Degrees in 48 Hours Shocked The Entire Meeting In…

End of content

No more pages to load