What Japanese Admirals Said When American Carriers Crushed Them at Midway

At 10:25 a.m. on June 4th, 1942, Admiral Chuichi Nagumo stood on the bridge of the Akagi, the morning sun glinting off the steel of his flagship, feeling the steady pulse of confidence that comes when a plan has finally reached its moment. The fleet around him was a marvel of coordination. Decks were packed tight with aircraft, meticulously arranged in wing tow positions, their engines idling like thoroughbred horses waiting for the starting gate. Crews moved across the planks with the precision of a finely tuned clock, each man aware of his place, each task executed in silence, rehearsed over countless drills. Fuel hoses snaked across the deck like veins, bombs and torpedoes rested in neat stacks, their lethal potential momentarily dormant but fully prepared for the strike his scouts had confirmed. On paper, it was a perfect equation. Four Japanese fleet carriers against perhaps three American carriers. The odds were favorable. The momentum seemed undeniable. Victory was within reach—or so it appeared.

Nagumo’s mind ran over the sequence one final time. The scout reports had been clear, the American carriers were within striking range, vulnerable to a well-timed strike. Every calculation, every forecast, had led to this precise moment. He allowed himself a fraction of satisfaction, a small, quiet smile, before a voice cut through the murmur of the bridge, sharp and insistent. Hands shot upward automatically in response to the order. Nagumo lifted his gaze and froze. The sky above the horizon, once empty save for the soft roll of clouds, was breaking apart in chaos. Dozens of dark shapes were plunging downward at impossible angles, their speed making them look like jagged streaks of smoke and shadow. Dive bombers. American dive bombers, fully committed, already past the point of no return.

Nagumo’s heart did not race. It should have, but there was no time for fear. Only calculation, only comprehension. In one instant, he saw the trap in its entirety. Aircraft still on deck, engines running, fuel hoses trailing, bombs and torpedoes exposed. Every plane ready to launch the Japanese counterstrike, every piece of ordnance live and volatile, and suddenly, it was all a death sentence. At 10:26, the first bomb struck near midship, a small, almost polite flash compared to what was about to follow. Then the chain reaction began. Armed and fueled planes detonated in rapid succession. The orderly lines of bombs and torpedoes erupted into a furnace of fire that raced across the flight deck like wildfire consuming a dry forest.

Nagumo was thrown against the rail by the initial shock wave, his body pressed and then released as the first flames licked across the deck. When he righted himself, the Akagi was no longer the living, breathing symbol of Japanese naval supremacy. It was dying, burning with a ferocity that made the hours of preparation seem cruelly ironic. Men shouted, orders flew, and through the acrid smoke, a single voice pierced the chaos: “Get down! The bridge will go!” But Nagumo did not move. He remained rooted, watching the Red Castle burn, the flagship that had led the audacious strike on Pearl Harbor just six months prior, now being devoured by bombs that had taken mere minutes to fall.

Smoke and heat rolled across the bridge, curling fingers of flame into the open air. Rear Admiral Runosuke Kusaka seized Nagumo’s arm with a desperation that betrayed years of discipline. “The flag must be shifted,” he urged. “Akagi is lost!” Soot streaked Kusaka’s face, his uniform torn from the heat and smoke. The deck below them twisted and warped in the rising inferno. Nagumo’s mind raced. What of the other carriers? His question was unspoken, but the answer came in Kusaka’s gaze. Kaga was a column of fire, Soryu a mirror of destruction, hit nearly simultaneously in the same merciless assault. Three of the four fleet carriers reduced to flaming hulks within five minutes of each other.

Nagumo felt a rupture inside himself. The doctrine he had lived by, drilled into him, celebrated as flawless, had failed in an instant. Carrier battles were meant to be simple: locate the enemy, strike first, destroy, and win. That formula had been the backbone of Japanese naval strategy for years. It had succeeded at Pearl Harbor, in the Indian Ocean, across distant theaters where speed, surprise, and superior planning had guaranteed victory. Japan always hit first. Japan always had the advantage. But this morning, on the skies above Midway, that advantage was gone.

The firestorms below the bridge were punctuated by the screams of men trapped on deck, the groans of twisted steel, and the relentless roar of explosions. Each detonation shook the very hull of the Akagi, each flash illuminating the horrified faces of crewmen as they fought against the inevitable. Fuel lines fed the inferno, bombs exploded with a rhythm almost impossible to comprehend, and planes ready for launch were nothing more than pyres of steel and fire. Nagumo’s mind traced every possible maneuver, every conceivable counterattack, but the reality was immediate and immutable. There was no room for calculation now. Only observation, only acknowledgment of the scale of disaster.

Kusaka and the other officers shouted over the din, issuing fragmented orders, trying to salvage what could be salvaged. But the reality was brutal and immediate. The enemy had exploited a single weakness—timing and surprise—and converted it into annihilation. The American dive bombers, appearing as if from nowhere, had committed themselves to the attack with a precision and coordination that defied expectation. Their sudden appearance, their dive angles, the speed of their approach, had rendered the Japanese fleet’s preparation irrelevant. Fuel, bombs, personnel, and deck planes—all potential weapons—had instead become catalysts for their own destruction.

Nagumo remained on the bridge, eyes fixed on the writhing chaos below. Time had slowed in his perception. Each second stretched, elongated by disbelief. The pride of the Combined Fleet, the carriers that had defined Japanese naval power, were burning with a cruel immediacy. The doctrine of striking first, the unassailable planning, the confidence in numerical and technological superiority—all of it had crumbled in a matter of minutes. And yet, the Admiral did not panic. Panic was for men who had no responsibility for millions of lives and the fate of the fleet. He absorbed the scene with cold, incomprehensible clarity, watching as the fire spread, as the planes ignited, as his command—the jewel of Japanese naval strategy—was consumed before his eyes.

Outside, the air was thick with smoke and the acrid scent of molten metal. Decks curled and buckled in the heat, planes fell into the sea with deafening splashes, and yet the assault continued, a perfect storm of timing, precision, and luck that defied all Japanese calculations. Kusaka, still gripping Nagumo’s arm, tried again to force a movement, a decision, a salvaging of what remained. The flag had to be moved, orders had to be sent, lives had to be preserved, but the immediacy of the inferno made every action secondary. The destruction was total, almost incomprehensible in its efficiency.

For a brief moment, Nagumo’s gaze traveled to the horizon, seeking some sign of the enemy, some hope of turning the tide, some escape from the inferno consuming the heart of his fleet. But there was nothing. Only smoke, fire, and the distant silhouettes of American dive bombers retreating with clinical detachment. The doctrine that had ruled Japanese naval warfare for years, that had brought them victories that reshaped the Pacific, had been shattered by a single, perfectly timed attack.

And in that suspended moment, as the heat and smoke enveloped the bridge, as men shouted, as alarms screamed, and the decks of the Akagi burned in uncontrollable fury, Nagumo and his staff understood a new reality. The calculation that had seemed so certain, the plan that had promised victory, the precision that had been the hallmark of Japanese naval prowess—all had failed. Three of four fleet carriers were wrecked within five minutes, the very foundation of the fleet decimated. The doctrine that had guided every maneuver, every strike, every engagement, no longer applied.

The horizon remained deceptively calm beyond the smoke, a pale blue untouched by the inferno. The sounds of destruction roared across the deck, but in the distance, the American carriers waited, their aircraft still ready, their crews still intact, their strategy relentless. The men on the Akagi bridge could only watch and absorb, realizing in the deepest part of themselves that the rules had changed, that the assumptions they had trusted were no longer valid, and that the war they thought they understood had suddenly transformed into something far more dangerous and uncertain.

Continue below

At 10:25 a.m. on June 4th, 1942, Admiral Chuichi Nagumo stood on Akagi’s bridge, thinking victory was minutes away. And then the sky opened. 300 miles northwest of Midway, the decks of his flagship were packed tight. Fighters and bombers sat wing towing, engines idling, crews moving like clockwork.

Fuel lines ran over the planks. Bombs and torpedoes waited in orderly stacks. Everything was staged for the strike his scout had finally reported. Four Japanese fleet carriers against maybe three American ones. On paper, it was a clean equation and it pointed to Japan. A voice snapped on the bridge and hands shot upward.

Nagumo lifted his gaze to the broken cloud layer. Dark shapes were dropping through it, dozens at once, knifing down in steep angles. US dive bombers. They seemed to appear out of nowhere. They were already committed, already too low to turn away. In one cold instant, Nagumo saw the trap.

Aircraft still on deck, hoses still connected, live ordinance still exposed. The worst timing imaginable. At 10:26, the first bomb struck a kaggi near midship. The blast looked almost small. Then the chain reaction started. Fueled armed planes detonated. The neat lines of bombs and torpedoes flashed into a rolling firestorm.

Seconds later, Akagi’s full flight deck was a furnace. The shock wave slammed Nagumo into the rail. When he stood again, his flagship was dying. Get down, someone yelled. The bridge will go. Nagumo didn’t move. He watched the Red Castle burn.

The same carrier that had led Keido Bhai at Pearl Harbor 6 months earlier. The greatest naval air force ever built was being erased by bombs that had taken only a few minutes to fall. Rear Admiral Runosuk Kusaka seized his arm. The flag must be shifted. Akagi is lost. Soot streaked Kusaka’s face. His uniform was torn. Smoke filled the bridge.

Through the windows, they could see deck plates curling from heat. The other carriers? Nagumo asked. Kusaka’s eyes answered before words did. Kaga a flame. Soryu a flame. Hit at nearly the same moment. Three of four fleet carriers wrecked within about five minutes. Something broke inside Nagumo. Carrier battles were supposed to be simple. Locate, strike first, win.

That doctrine had ruled Pearl Harbor, the Indian Ocean everywhere. Japan always hit first. Not today. The Americans had struck first and with perfect timing, catching every deck crowded during rearm and refuel. It felt as though the enemy had known the schedule, as though they had planned the instant.

Kusaka tugged him toward the ladder. Smoke thickened. Ammo cooked off below in sharp pops. Bridge crews were already fleeing down ladders. Nagumo took a last glance at the chart table. The confident arrows toward American carriers that were meant to be destroyed. Then he followed into the haze.

On the flight deck, it was chaos. Planking burned despite firefighting teams. Planes popped and tore apart. Fuel spilling in burning rivers. Men ran with hoses. Ran from explosions or ran because there was no safe place left. Bodies lay where the first blast had caught them. The air rire of aviation gas, cordite, and scorched flesh.

Captain Taro Aoki, Akagi skipper, stood near midship, barking orders, horse from smoke, shouting. Seeing Nagumo, he saluted with a shaking hand. The admiral must abandon ship. We cannot save her. “Your crew?” Nagumo asked. Lower decks were evacuating, Aayoki said. But flames were spreading toward the hangar where fueled armed aircraft sat. No explanation was needed.

If fire reached that space, Akagi would explode inward. Destroyer Noaki edged alongside. The transfer was frantic. Nagumo and staff climbed rope ladders as a kagi rolled harder, taking on water through ruptured plates. From the ladder, he saw Kaga two miles south, burning worse than a kagi, her island swallowed by flame.

Farther out, Soru listened with black smoke pouring skyward. Only hear you 10 miles away, looked untouched. On Noaki’s deck, Nagumo watched his flagship burn while officers stood in stunned silence. These were the planners of Pearl Harbor, the men who had sunk Hermes at Cornwall off Salon and driven the Royal Navy from the Indian Ocean.

They had believed themselves unstoppable. Carrier warfare was their science. Yet, Commander Minoru Jenda Nagumo’s air operations officer was openly crying, repeating. How did they know? How did they know when to hit? He whispered again. No one could answer. A signal officer brought a flimsy Rear Admiral Tammen Yamaguchi on Hiru reported himself undamaged and ready to launch on the American carriers. Nagumo read it.

Doctrine demanded a swift counter blow while the enemy recovered. It was correct. It was what Nagumo would have ordered if his mind weren’t numb. Acknowledge, he said, and tell Yamaguchi he has full authority. It was an unspoken admission. Akagi burning, staff scattered, calms shattered, Nagumo was no longer really commanding.

With an intact carrier and crew, Yamaguchi now led what remained. What was left of it? Afternoon reports came in, each worse. Hiru’s strike found Yorktown and damaged her badly. For a moment, hope flickered. Maybe one American carrier knocked out could still swing the day. Then around 5:00 p p.m. another signal from here. Enemy dive bombers overhead.

Nagumo stood on Noaki’s bridge with binoculars as 10 miles away here vanished under bomb splashes. When the water cleared, she too was on fire. All four carriers, Akagi, Kaga, Soryu, Hiru, were destroyed in a single day. In under seven hours, the strike force that had ruled the Pacific for 6 months had ceased to exist. Kusaka approached softly.

They needed guidance for combined fleet Ashu. Yamamoto had to be told what happened and whether to press on or withdraw. They needed decisions. Nagumo couldn’t think. His mind looped back to the bombs appearing through clouds. If the scout had found Americans an hour earlier, if his own launch had gone 30 minutes sooner if US planes had arrived 30 minutes later, any small shift might have changed everything.

But none had. The Americans hit at the one flawless moment of Japanese vulnerability. Now those carriers were gone. Signal combined fleet. Nagumo said at last, all four carriers struck and burned. Request instructions. 300 m west on the battleship Yamato, Admiral Izuroku Yamamoto received the first shattered messages around 11 a.m. They were confused.

Akagi bombed, Kaga a flame, Soryu burning. Yamamoto read them with a face like a stone. Captain Kameo Kroshima watched closely. Yamamoto was small, quiet, and famed for a poker mask. He had warned Japan could run wild for 6 months to a year, but promised nothing after.

Exactly 6 months after Pearl Harbor, his forecast was coming true. Confirmation? Yamamoto asked. Still waiting, sir. Comms were broken, but multiple reports pointed to heavy damage to at least three carriers. Yamamoto studied the chart. His midway plan was elaborate, perhaps too elaborate, with a carrier force in front. His battleships, including Yamato 300 m behind. The aim was to lure the Americans into a decisive surface fight.

But Yamamoto knew carrier wars were decided in minutes. Battleships could not arrive in time. And if Nagumo’s carriers were lost, another flimsy arrived. Yamamoto’s control slipped. His hand trembled. All four carriers hit. All burning. Kaga and Soryu sinking. Akagi and Hiru are afloat, but fires are raging. He walked to the bridge windows and stared at the empty sea.

Around Yamato steamed the strongest surface fleet Japan had ever gathered. 11 battleships, many cruisers and destroyers, transports carrying 5,000 troops for midway. All of it helpless without air cover. All of it exposed to American carrier planes. The American carriers? Yamamoto asked.

One reported damage by here. Maybe two others still sound. So, America still had carriers while Japan now had none. The math was brutal. Carriers ruled the ocean. Without them, battleships were targets, magnificent, strong, and useless. Chief of Staff Admiral Maté Ugaki stepped in carefully.

They could still seek a night surface action. Japan held overwhelming gunnery power. Yamamoto replied that Americans would not oblige. They could stand off and pound with aircraft. Japan could neither reach them nor defend. How long until we’re within range of Midways land planes? Yamamoto asked. The chart said about 8 hours.

Of course, we’re held and there was no air cover. The implication was clear. push on and the fleet would be hammered by island-based bombers defended only by flack. Maybe battleships survive, but cruisers and destroyers would be slaughtered. And for what? To shell an island. They could no longer invade without air superiority. Signal all forces. Withdraw northwest. Yamamoto ordered. Ugaki stiffened.

Operation over. Yamamoto’s voice stayed flat. Four carriers lost. Americans perhaps won. They could not continue. Ugi noted. Nagumo was still requesting guidance. Yamamoto cut in. Nagumo has no force left. His decks burn. His aircraft lie on the seabed. What do you expect him to do? Ugaki had no answer.

Yamamoto looked out again. The ocean was calm, indifferent. Over the horizon, four famed carriers were dying. Their names had been legend since Pearl Harbor. Now they were gone, destroyed by an enemy meant to be surprised and beaten. “I miscalculated,” Yamamoto murmured. “I said we could run wild for 6 months.

It has been 6 months.” “No one spoke on Yamato’s bridge.” Younger officers stared at instruments, refusing to watch the moment Japan’s offensive ended. Yamamoto straightened. Control returning. Break off. Withdraw. Keep searches up. Avoid enemy carriers and get a final damage report. Could any carrier be saved? Within the hour, the answer arrived. Akagi abandoned.

Fires beyond control. Kaga sinking. Soru is already under here. Youu is still afloat, but burning toward magazines, none salvageable. All would be on the bottom by morning. Yamamoto read methodically, revealing nothing, then dismissed staff, and stood alone at the windows. A junior officer later said he heard the admiral speaking quietly to himself, words indistinct.

Some later claimed he apologized to the emperor. Others believed he was already calculating what the loss meant. Back on Naki, Nagumo watched the sunset on June 4th. Debris and survivors dotted the sea. Destroyers hauled hundreds from the water, burned, wounded, exhausted. Akagi still floated, still a flame. Her deck collapsed, her superructure twisted.

Captain Aoki had begged to die with her. Nagumo ordered him off. Death was already plentiful. Night brought Yamamoto’s order. Scuttle Akagi. Too damaged to save, too risky to leave a drift for US submarines. Four destroyers fired torpedoes. At 500 a.m. on June 5th, Akagi slipped under. Nagumo watched without speaking. His officers stood gray with shock.

Jenda finally tried to comfort him. It wasn’t your fault. Americans broke our codes. They positioned themselves perfectly. Nagumo cut him off. It doesn’t matter. We lost and that is all. Silence returned. Four carriers, hundreds of aircraft, over 2,000 men gone. The force thought invincible had been shattered in one day. On hereu, the last carrier to die.

Rear Admiral Yamaguchi remained on the burning bridge. crew evacuated. Fires raged. Staff begged him to transfer to a destroyer. He refused. He had commanded Hiru through every battle since Pearl Harbor. Even the strike that crippled Yorktown. He would not abandon her. Captain Toéoku said he would stay, too.

They sent staff away, ordered the final evacuation, and stood together as flames closed in. The last men leaving reported seeing the two silhouetted against fire facing toward Tokyo and the emperor. Some said they sang. Others said they stood at attention. At 2 a.m. June 5th, Hiru’s magazines blew. She broke apart and sank in minutes.

Yamaguchi and Kaku went down with her. When the news reached Yamato, Yamamoto received it in silence, then withdrew to his cabin for 12 hours. Worried staff sent the fleet doctor. The doctor found the admiral seated at his desk, staring at a photograph of the four carriers as they had looked at Pearl Harbor, decks crowded, flags flying, seemingly unbeatable. The retreat itself was a disorder.

Yamamoto’s forces scattered on different headings, keeping radio quiet against submarines. Invasion transports turned back. Battleships meant to pulverize midway, steamed away into darkness. Months of planning dissolved in one night. On Noaki, Nagumo wrote his report for Combined Fleet HQ. His hand shook.

How did you explain four carriers lost in one day? How did you describe your flagship burning? How did you report that Kido Bhutai no longer existed? Kusaka found him at dawn June Feb. He urged rest. Nagumo looked up, eyes red. He said he should have known the scout delay. The Americans arriving at the precise vulnerable moment. They knew where Japan was, what it was doing, when to hit.

They could not have known codes were broken. Kusaka said. Nagumo replied he should have assumed the worst, not that Japan would surprise and strike first as always. He looked at the half-written paper and said, “Now four carriers were gone, 2,000 men dead, and it was his fault.” Kusaka could not answer.

It was his fault because he commanded yes. It was also Yamamoto’s for spreading forces too thin and Navy ministries for trusting codes. It was every officer’s fault for believing early victories meant invincibility. Blame could be shared widely. Still, Nagumo was right in one sense. He had led the carriers and he had lost them. Over the next days, the scale sharpened.

Four fleet carriers sunk, 322 aircraft destroyed, 2,200 killed, including some of Japan’s best air crews. The elite of naval aviation, men trained for years over China, Pearl Harbor, the Indian Ocean, wiped out in a day. And for what? Americans lost Yorktown, sunk by a submarine two days later.

One carrier traded for four. America could replace Yorktown with its vast industry. Japan could not replace Akagi, Kaga, Soryu, and Hiryu. Neither ships nor trained pilots. Yamamoto saw this immediately. Within days, he was drafting a defensive posture once unthinkable.

Japan would consolidate holdings, fortify islands, and raise the cost of American advance. The offensive was done. The dream of dominating the Pacific was done. Now it became holding on, making America pay for every atoll, hoping the US would tire and negotiate. Yamamoto knew that hope was fantasy. America would not tire or bargain. It would build more carriers, train more pilots, and move west in overwhelming mass.

Midway had not only halted Japan’s drive, it sealed Japan’s end. On June 10th, Nagumo’s shattered force limped into Hashiima anchorage. The carriers were missing. The destroyers and cruisers that returned were battered, low on fuel. Crews stunned. Nagumo shifted from Noaki to a cruiser and prepared to face the Navy Ministry.

He expected court marshal relief, maybe forced suicide. Instead, the ministry hid the disaster from the public by giving him another post. They could not admit their star admiral had failed or that Keo Bhai was destroyed. So, they promoted him and treated Midway as a smaller setback. Nagumo knew otherwise.

He had watched dive bombers fall through clouds, seen carriers burn, seen 2,000 men die. Propaganda could not rewrite that. Nothing could bring back a kagi kaga sore you hear you. Years later, after defeats piled up and war became a grinding series of island fights and kamicazi raids, Nagumo would command Saipan’s defense.

When that island fell, with no hope or escape, he would finally end his life with a pistol, an act that admitted failure since midway. But on June 10th, 1942, standing on a cruiser deck at Hashiraima, staring at an empty sea where his carriers should have been, he said nothing. The staff waited for directions. He had none. He had led the greatest carrier force in the world and lost it in a day.

What followed would be defeat, retreat, and the slow grinding away of everything Japan had won in six months. He could not say that, so he stayed silent, remembering the moment the bombers appeared and knowing everything had flipped. On Yamato, Yamamoto read casualty lists. Over 2,000 dead, hundreds wounded, four carriers sunk.

He filed reports, wrote an assessment, then sat alone with that Pearl Harbor photograph. Later, someone asked what he felt reading those names, understanding Midway. He only shook his head and said he had warned them they could run wild six months, and it had been six months. Japan had wagered on quick victory, on breaking America’s will before its factories mobilized.

It lost that wager at midway in a single morning when four carriers burned and sank and dragged Japan’s offensive to the Pacific floor. What did the Japanese admiral say as American carriers destroyed their fleet? Mostly nothing. No words could reverse the smoke, the fires, the lost men. They stood on shattered bridges, watched the ocean, and understood the war was already decided, even though it would drag on three more years.

They had lost everything in one day to an enemy they had underestimated and to their own belief in invincibility. So they fought on in silence, retreating step by step until the end came. Near the close of that long road, remember to like the video and subscribe for more stories like this. Nagumo had spent the morning believing the decisive blow was finally in his hands.

The scout report had been late, but now it was here, and the deck teams were hustling to turn that information into a launch. He could hear the engines coughing to life, smell fuel in the air, and see the yellow shirted crews waving planes into position. Every drill he had practiced said this was the moment Japan’s carrier arm lived for.

Yet, the dive bombers were already falling. There was no time to clear the deck, no time to shove fueled aircraft into the hangar, no time to pull hoses or roll ordinance away. The attack arrived when the carrier was most fragile, when everything combustible and explosive sat out in the open. It turned the flight deck into tinder.

The small first detonation fooled no one for long. The follow-on blasts ripped through the parked planes, and each exploding aircraft fed the next. Fire raced across planking. Steel warped. Smoke boiled up the island. Officers shouted orders that vanished beneath the roar. Nagumo’s bridge windows became a frame for a scene he could not fix.

As Kusaka pulled him down, Nagumo felt the sick realization that doctrine had betrayed him. The Japanese Navy had built its early war around striking first, and Midway had been planned as another trap to force that first blow. Instead, the first blow landed on them. Below, damage control parties tried to fight a losing battle.

Hoses spat foam into heat so intense it flashed water into steam. Ammunition lockers popped. Aircraft tires burst. The ship’s list grew as water flooded compartments. Every minute made evacuation harder. When Milwaukee drew close, ropes and ladders swung between ships. Men clambered down as a kagi rolled, sometimes slamming against the destroyer’s hull.

One slip meant a fall into burning fuel on the sea. Officers tried to keep order, but order was evaporating with the smoke. Distant explosions echoed across the water from the destroyer. Nagumo could see Kaga’s flames reaching high behind her island and saw you trailing smoke like a black banner.

Here you still intact looked almost unreal, separated from the inferno. It was the last sharp piece on a board that had just been swept clean. The staff around Nagumo were not only shocked, they were hollowed out. These were veterans who had watched American bases explode at Pearl Harbor and had seen British carriers sink off Salon.

They had looked at carrier warfare as settled math. Now their math had failed in front of their eyes. When Jenda asked how the Americans knew, the question carried terror as much as confusion. He said it over and over as if repeating it could summon an answer.

None came because there was nothing in their experience that explained such perfect timing. Except the possibility that their secrets were no longer secret. Yamaguchi’s counter strike launched from Hiru was the only move left on the board. It was fast, brave, and entirely by the book. Hearing that Yorktown was burning gave Nagumo a momentary lift.

His mind grabbed for any sign that the disaster might be reversible. But the second American wave arrived with the same cruel precision. Hiu’s flight deck, like the others earlier, erupted under bombs. Watching through binoculars, Nagumo could trace the silhouettes of plunging planes, the tall spouts of water, the sudden bloom of smoke.

He knew even before all the reports that there would be no fifth carrier to rally around. On Yamato, Yamamoto’s staff watched their commander absorb the news. They had all understood his midway scheme only worked if carrier air power survived to shield the surface fleet. Without it, the battleships behind the carriers were little more than targets.

Ugi’s suggestion of night battle was logical in a world of gunnery. But this new world belonged to aircraft. Yamamoto said so plainly. The Americans could stay beyond gun range forever, sending out strike after strike while Japan steamed blind beneath them. The decision to retreat was not cowardice. It was arithmetic.

Every mile toward Midway without air cover invited land-based bombers to descend on ships that could not dodge at sea speed. Yamamoto chose to save what he could of the surface fleet because the alternative was senseless loss. After the withdrawal order went out, the once coordinated Japanese armada became a scattering of columns and solitary ships. Radio silence necessary against submarines made that scattering worse.

Each commander had to guess at the others headings in the dark. The invasion convoy meant to deliver troops under carrier shelter turned back like a hand withdrawn from a flame. Nagumo’s night on Noaki was long. Survivors were hauled aboard, some barely able to speak, their skin burned raw, their uniforms stiff with salt and fuel.

The sea around them glowed in places where aviation gasoline still burned on the surface. Akagi, still visible in the distance, looked like a dying city. When the torpedoes finally pushed her under at dawn, it felt like the closing of an era. The red castle that had symbolized Japan’s naval ascent was now a tomb.

Nagumo watched until the last ripple flattened. Yamaguchi’s choice to go down with Hiru was the final echo of that era’s mindset. In the face of inevitable loss, he clung to the ship that had carried him through triumph after triumph. His and Kaku’s refusal to leave was not theatrics.

It was the only answer they knew in a world where honor and command were fused. Yamamoto staring at the Pearl Harbor photo underscored the same rupture. The image represented a navy at its peak. aircraft lined up, flags snapping, men confident that the Pacific was theirs. Now those same decks were underwater and the men in the photo were dead or scattered.

Nagumo’s report to headquarters was written with the weight of that understanding. He had to explain the unexplainable. Four carriers gone, pilots and deck crews, Japan’s irreplaceable professionals burned or drowned. He replayed every delay and decision, each if that might have prevented the catastrophe, and each if that was now meaningless.

The Navy Ministry’s choice to mask the disaster with promotions was another form of silence. Publicly, Midway would be softened, explained away, treated as a bump. Privately, every officer who understood industrial reality knew the truth. Japan could not rebuild a carrier force of that quality, especially not the seasoned aviators who had made the early strike so deadly.

By the time Nagumo later faced Saipan’s collapse, he had already lived through the moment Midway broke his faith. His death there sealed Midway as the turning point of his life, though he did not say so aloud at the time. And Yamamoto, even before the war’s later disasters, grasped what Midway meant. The United States would not be worn down.

It would multiply its strength. Japan’s job had shifted from conquering to merely delaying. The retreat from Midway was the first step on that long, losing road. One more report after another reached the retreating fleet, each confirming what everyone already felt. Akagi’s fires had spread unchecked. Kaga’s crew had abandoned hope of stopping the blaze.

Soryu was already gone beneath the waves. Hiru’s remaining men could only watch flames crawl toward the magazines. There was no hidden reserve, no secret fifth carrier, no late arriving miracle. The heart of Japan’s naval airarm had been cut out in daylight. For Nagumo, the shock was not only tactical, it was personal.

He had built his career around the promise that careful preparation and first strike would decide everything. That morning he had watched his deck crews carry out that preparation with flawless discipline. Then without warning a handful of American squadrons had ended it all inside minutes. The gap between expectation and reality felt like a physical wound.

Yamamoto’s own stillness was similar. He did not rage because there was nothing to rage at. His earlier opposition to war with America was rooted in industrial math, and the events off Midway only confirmed that math. When he told his staff to withdraw, he was already picturing American shipyards filling the Pacific with new carriers, while Japan scrapped for replacements.

He understood that Japan’s margin for error had vanished that morning. That is why the recollections from Midway are filled with quietness. There were a few lines spoken on burning bridges or in dark cabins, but most of the commander’s response was silence. Silence born of comprehension. They knew the offensive phase had ended, even if the fighting had not.

They knew they were now playing for time against a power that could outbuild them. The waves around Midway carried away the carriers, and with them the illusion of inevitability. In the days after, every survivor and every officer sensed the same thing. A door had closed.

The Navy that had surged across the Pacific now had to pull back, patch wounds, and hope for chances that would never truly return. Midway was not just a lost battle. It was the moment confidence bled out, leaving only duty and endurance. From that hour, Japan fought a war it could no longer

News

CH2 Japanese Soldiers Were Terrified When U.S. Marines Used Quad-50s to Destroy Their Banzai Charges

Japanese Soldiers Were Terrified When U.S. Marines Used Quad-50s to Destroy Their Banzai Charges The morning of February 8th,…

CH2 How a U.S. Sniper’s ‘Car Battery Trick’ Killed 150 Japanese in 7 Days and Saved His Brothers in Arms

How a U.S. Sniper’s ‘Car Battery Trick’ Killed 150 Japanese in 7 Days and Saved His Brothers in Arms …

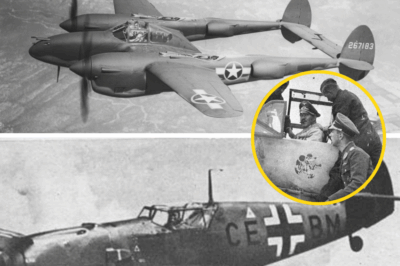

CH2 German Pilots Were Shocked When P-38 Lightning’s Twin Engines Outran Their Bf 109s

German Pilots Were Shocked When P-38 Lightning’s Twin Engines Outran Their Bf 109s The sky over Tunisia was pale…

CH2 When The Germans Saw The American Jeep Roaming On D-Day – Their Reaction Showed How Doomed Germany Was…

When The Germans Saw The American Jeep Roaming On D-Day – Their Reaction Showed How Doomed Germany Was… June 7th,…

CH2 What Eisenhower Told His Staff When Patton Reached Bastogne First Gave Everyone A Chill

What Eisenhower Told His Staff When Patton Reached Bastogne First Gave Everyone A Chill In the bitter heart of…

CH2 The “Ghost” Shell That Passed Through Tiger Armor Like Paper — German Commanders Were Baffled

The “Ghost” Shell That Passed Through Tiger Armor Like Paper — German Commanders Were Baffled The morning fog hung…

End of content

No more pages to load