What Eisenhower Told Staff When Patton Turned His Army 90 Degrees in 48 Hours Shocked The Entire Meeting

In the bitter cold of December 1944, the war in Western Europe seemed, for a brief and deceptive moment, to have entered a lull. The thunder of artillery that had once shaken the French countryside now echoed less frequently. Supply convoys rumbled eastward through liberated towns, soldiers huddled in tents dreaming of home, and generals spoke in cautious optimism. The Allies had broken through Normandy, swept across France, and liberated Belgium. From Eisenhower’s headquarters, it appeared the war was tilting decisively toward victory. The German army, bloodied and retreating, seemed on its last legs.

Supreme Allied Commander Dwight D. Eisenhower, pragmatic and deliberate, studied the front lines with the calm detachment of a man who had spent years reading maps of war. He knew the enemy could still fight fiercely, but the idea that Hitler’s forces could launch another large-scale counteroffensive was dismissed by most of his staff as impossible. The German army, they believed, was fractured—its divisions understrength, its fuel reserves nearly gone, its morale broken by the relentless Allied push. Winter, they thought, would bring hardship, but not surprise.

Yet, deep within the frozen forests of the Ardennes—a stretch of dense, snow-covered terrain between Belgium and Luxembourg—the enemy had been quietly preparing something no one at Allied command had foreseen. The forests muffled the rumble of engines and the grinding tracks of tanks. The fog concealed movement, hiding divisions that had been secretly rebuilt and rearmed. Hitler’s generals, desperate to reverse the course of the war, had gambled everything on one last, audacious strike.

On the morning of December 16th, 1944, that gamble came to life. Before dawn, the stillness shattered under the roar of artillery. More than 200,000 German troops surged through the fog. Over 1,400 tanks and assault guns rolled forward across a front the Allies had deemed “quiet.” The offensive—Operation Wacht am Rhein, which the world would later know as the Battle of the Bulge—hit the unsuspecting American positions like a hammer. Entire regiments were engulfed before their commanders even understood what was happening.

In hours, the German advance drove a deep wedge through the Allied line. Roads became choked with retreating vehicles. Communication lines snapped. Units were cut off, surrounded, and overwhelmed. Radio operators sent frantic messages that broke up in static. The snow fell harder, burying the chaos under a deceptive calm. What Eisenhower had assumed would be a slow winter of consolidation suddenly became the gravest crisis since D-Day.

The blow fell hardest in the Ardennes—terrain thick with pine forests and narrow, twisting roads that favored the defender. But the Americans had not expected to defend there at all. Intelligence reports had suggested that the Germans no longer had the strength to launch a major operation. Those reports were wrong. Now, Allied headquarters in France was a storm of confusion. Maps were spread across tables, covered with grease pencil lines and red arrows that grew longer by the hour as German units poured west.

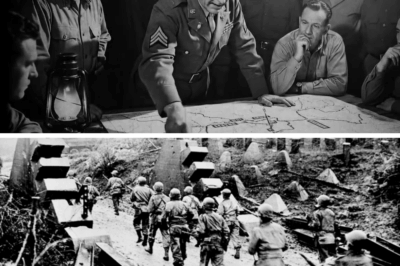

At SHAEF headquarters, Eisenhower’s staff scrambled to make sense of reports that changed by the minute. Some divisions were missing entirely, communications lost. Others had been forced to withdraw under relentless pressure. By December 19th, the situation was desperate enough that Eisenhower ordered an emergency conference in Verdun, France—a place already etched into military history as a symbol of endurance from the Great War.

The meeting room in Verdun was cold, its walls thick with stone, its air heavy with tension. Around the long table sat the commanders who held the fate of the Allied advance in their hands: Omar Bradley, the calm strategist of the Twelfth Army Group; Courtney Hodges, his nerves frayed from the unfolding disaster; and across from them, George S. Patton, commander of the U.S. Third Army.

Patton entered wearing his signature ivory-handled pistols, the metal gleaming under the dim light. His presence carried a force of its own. He was the kind of man whose confidence felt almost physical, a current that filled the room whether people wanted it there or not. He had the sharp eyes of someone who saw opportunity in chaos, and as Eisenhower began the briefing, Patton was already thinking ahead.

Eisenhower laid out the situation with measured clarity. The Germans had achieved what no one thought possible. Their offensive had carved a massive “bulge” into the Allied line. The 101st Airborne Division was trapped in the small Belgian town of Bastogne, surrounded on all sides. Roads critical to the Allied supply network were falling one after another. The weather, thick with low clouds, had grounded Allied aircraft, leaving the skies to the Luftwaffe. And the German advance—fueled by surprise and momentum—was moving faster than anyone had planned for.

Eisenhower’s tone was calm, but the strain showed in his face. He knew this was the kind of moment that defined commanders. “Gentlemen,” he said, pointing to the map, “the enemy has achieved a major penetration. We must act before that bulge cuts our armies in two.”

Around the table, the responses came slow and cautious. Bradley spoke first, his voice even but grave. Redeployment in winter, he warned, would be a nightmare. The roads were iced over. Convoys were already jammed with retreating units. Fuel was scarce. To turn entire divisions around—especially armored columns—and send them north through that terrain could take days, even a week. Hodges agreed. His men were already fighting to hold the line. Reinforcements could take too long.

The room was heavy with realism, every general balancing risk and logistics, every mind trapped between urgency and impossibility. The air felt thick enough to stop sound. Eisenhower listened, nodding, his expression unreadable. Then, when the others had finished, he turned to Patton.

“George,” Eisenhower said, “how soon can you attack?”

Every head turned. The question was both simple and impossible. Patton’s army was currently engaged hundreds of miles to the south, facing east toward Germany. To intervene in the north would mean turning the entire Third Army—a force of hundreds of thousands of men, tanks, trucks, and artillery—ninety degrees across winter terrain clogged with ice, snow, and retreating traffic. It was, by any standard, an extraordinary logistical feat.

But Patton didn’t hesitate. He leaned forward, the faintest trace of a grin on his face.

His reply came quick, almost casual, as if the question were trivial. “Two days,” he said.

The room fell silent. For a moment, no one spoke. Eisenhower stared at him, half-incredulous. “You mean to tell me,” he asked, “you can disengage your divisions, pivot them ninety degrees, and attack into the flank of the enemy in forty-eight hours?”

Patton nodded once. “That’s exactly what I mean.”

It wasn’t bravado. Weeks earlier, while others believed the German front was collapsing, Patton had suspected otherwise. He had seen the faint signs—the unusual radio silence, the subtle movement of German reserves, the quiet in sectors that should have been loud with skirmishes. And because he never trusted anything the enemy did to make sense, he’d prepared three separate contingency plans, each one detailing how his army could pivot north at a moment’s notice.

Now those plans sat ready in his operations tent, neatly typed and rehearsed. All he needed was Eisenhower’s order.

Around the table, his fellow generals exchanged uneasy looks. Some thought he was bluffing, others thought he was mad. The scale of what he was proposing bordered on the impossible. To turn an entire army ninety degrees in winter, over frozen roads and through narrow mountain passes, would require coordination that bordered on orchestral perfection. But Patton’s staff had already begun preparing before he even walked into the room.

Eisenhower studied him for a long moment. The air between them was thick with calculation and something unspoken—a mutual understanding that moments like this decided wars. The other generals waited for Eisenhower to laugh it off, to tell Patton to be realistic. But Eisenhower didn’t. He just looked at him, a faint, knowing smile at the corner of his mouth.

It was then, in that heavy silence, that Eisenhower said something his staff would remember for the rest of their lives.

He didn’t raise his voice. He didn’t move from where he stood. He simply nodded once and said, “Alright, George. Let’s see you do it.”

And with that, the meeting ended.

The generals filed out into the cold Verdun air, the wind cutting across the courtyard, carrying with it the low growl of trucks somewhere in the distance. The war was moving again. In that quiet, snow-dusted moment, as maps were folded and orders prepared, no one in that stone fortress could yet comprehend what would happen next—how one army, under one man, would perform a maneuver so fast, so precise, that even the Germans refused to believe it was real.

For now, all anyone knew was that Patton had made a promise. And in forty-eight hours, the world would find out if he meant it.

Continue below

In the closing winter of 1944, the Western Front appeared, at least on the surface, to have reached a moment of relative stability. Allied forces, having successfully broken out of Normandy and liberated vast regions of France and Belgium, were pressing steadily toward the German border. Supreme Allied Commander Dwight D.

Eisenhower believed that the Wehrmacht had been pushed to the brink, too depleted and disorganized to mount large-scale counteroffensives. The Allied command expected a difficult winter with slow progress and supply challenges, but nothing that suggested a dramatic change in the strategic balance.

The belief that German forces could still orchestrate a major strike seemed improbable. That assumption was shattered on the morning of December 16th, 1944 when Adolf Hitler launched Operation Vak Amrin, known today as the Battle of the Bulge. In a stunning display of secrecy and concentration, the Germans deployed more than 200,000 troops, 1,400 tanks, and thousands of artillery pieces through the densely forested Arden region.

The attack struck a thinly defended segment of the American line. Overwhelming units that were unprepared for such a massive assault. Communication networks collapsed, supply lines were severed, and American commanders struggled to understand the magnitude of what was unfolding. Within hours, the German offensive created chaos along a wide section of the front, and Allied headquarters found itself confronted with one of the most serious crises since the Normandy landings.

As the situation deteriorated, Eisenhower urgently summoned his senior field commanders to an emergency meeting at Verdun on December 19th. The choice of location carried historical weight. Verdun had been a symbol of endurance and crisis during World War I. And now once again, it became the site of a crucial turning point.

Among the assembled generals stood George S. Patton, commander of the US Third Army, a figure whose reputation for aggression, speed, and audacity was unmatched. Patton entered the meeting already calculating opportunities even while others were still struggling to assess the scale of the problem. What made Patton different in this moment was not simply bravado but preparation.

While many Allied commanders had considered the Ardens a quiet sector, Patton had maintained a persistent suspicion that the Germans were not yet finished. He instructed his intelligence staff to monitor unusual German troop movements. And when reports trickled in suggesting increased enemy activity, he took them seriously.

Weeks before the German offensive even began, Patton quietly ordered his operations officers to draft contingency plans for a rapid pivot to the north. As a result, when the German attack broke through American lines and chaos spread, Patton already possessed three detailed operational plans, outlining how his army could quickly abandon its current offensives and wheel northward to counter the threat.

This remarkable situation set the stage for one of the most dramatic command interactions of the entire war. At the Verdun conference, Eisenhower opened the meeting by acknowledging what everyone already feared. The German offensive had created a deep widening penetration that threatened to split the Allied armies. The 101st Airborne Division was isolated in Baston.

Major road junctions were falling. The weather had grounded Allied aircraft, and the enemy seemed to have achieved total strategic surprise. Eisenhower needed solutions, and he needed them quickly. When he turned to his field commanders, most offered cautious, conservative estimates. Redeploying major formations in winter conditions on icy roads with traffic jams stretching for miles would be extremely difficult.

Some estimated that it could take up to a week to reposition sufficient forces to mount a meaningful counterattack. The tone of the room was somber, filled with uncertainty and logistical concerns. Then Eisenhower looked at Patton. George,” he asked, “How soon can you attack?” Patton did not hesitate. He responded immediately, almost casually.

I can attack with three divisions in 48 hours. The room fell silent. Several officers reportedly stared at him, unsure whether he was serious or attempting to break the tension. Bradley’s staff exchanged looks of disbelief, and even seasoned logisticians present in the room struggled to comprehend the magnitude of what Patton was proposing.

Moving an entire army was not simply a matter of marching troops. It required reorganizing traffic control, supply routes, fuel distribution, artillery positioning, and coordination between countless units spread across hundreds of kilome. Attempting such a maneuver in ideal weather would be extraordinary. Doing it in snow, ice, and fog seemed impossible.

But Patton had a hidden advantage. He had already prepared for this exact moment. When Eisenhower asked how soon he could attack, Patton was not improvising. He had anticipated the possibility of a German offensive and had instructed his staff to construct detailed plans for a northward pivot. As he explained to the stunned officers at the meeting, he had multiple routes and timets ready.

All he needed was approval to execute one of them. His confidence was not bravado. It was the product of meticulous planning, relentless training, and an instinct for anticipating enemy actions. Eisenhower took a long moment to study Patton. He understood that if Patton was correct, the Third Army might be the only force capable of reaching Baston in time to prevent catastrophe.

Eisenhower knew the stakes. If Baston fell and the Germans exploited their breakthrough, they could drive all the way to the Muse River and potentially sever the Allied front. The fate of the campaign, perhaps even the war in Western Europe, depended on fast, decisive action. Finally, Eisenhower spoke, delivering the now famous line remembered by several officers in attendance.

Okay, George, you have the green light. If anyone can do it, you can. With those words, the most daring tactical pivot of the European theater began. Patton left the conference without ceremony, immediately contacting his staff to initiate the complex process of turning his entire army 90° and driving it north. After Patton departed, Eisenhower addressed the remaining officers.

His remarks, recorded in various diaries and afteraction reports, reveal a mixture of astonishment and resolve. He told his staff that Patton’s proposal was the most audacious operational maneuver he had heard during the entire war, but also the one most likely to succeed given the circumstances. He emphasized that patent had to be supported with every available resource, fuel, priority road access, traffic control, and communication channels.

Eisenhower reportedly added, “Patton may be the key to saving the whole front,” underscoring the gravity of the situation. What Eisenhower recognized in that moment was the unique value of Patton’s leadership. Patton was not merely aggressive. He possessed an almost unparalleled ability to translate strategic opportunity into operational action.

While others hesitated, Patton acted. While others doubted, Patton prepared. The Third Army’s pivot would soon be hailed as one of the greatest logistical achievements of the war, an embodiment of speed, discipline, and organizational excellence. By the time Eisenhower finished briefing his staff, the wheels of Patton’s army, figuratively and literally, were already turning.

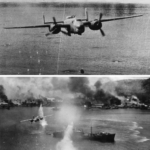

Convoys were rerouted. Supply trains shifted direction. Divisions preparing for offensive operations in one sector were suddenly ordered to march through freezing snow toward a new battlefield. No army in modern history had ever attempted such a dramatic reorientation on such short notice. Yet within hours, Patton’s headquarters was executing the plan with precision.

What Eisenhower told his staff in the aftermath of that meeting was not only an endorsement of Patton’s audacity, but also a recognition of the crucial reality. In the darkest moment of the Allied campaign, one general had both the foresight and the determination to attempt the impossible. As Patton departed the command conference at Verdon, the urgency of the situation pressed upon every aspect of the Allied command structure.

The German advance was not slowing. If anything, it was accelerating. Reports arriving at Eisenhower’s headquarters indicated that multiple American divisions were either retreating in disorder or fighting desperately to hold isolated positions. Baston, one of the most crucial road junctions in the Arden, had been encircled.

The 101st Airborne Division, reinforced by elements of the 10th Armored Division, was holding the town against repeated German assaults. But their situation was increasingly precarious. Ammunition was limited, medical supplies were dwindling, and the freezing weather compounded the misery. If relief did not arrive soon, the defenders might be overwhelmed.

Against this backdrop, Patton’s promise to turn his army 90° in 48 hours may have sounded to some like hubris, but the general was already several steps ahead of his peers. On returning to his headquarters, he immediately convened his staff officers and issued orders with a clarity and forcefulness that left no room for doubt.

The army would pivot north. Every available division would prepare for rapid movement and the entire logistical infrastructure of the Third Army would be reoriented to support the advance. Officers who had attended the Verdun conference later recalled the electric atmosphere inside Patton’s headquarters. They described how a sense of controlled chaos overtook the command post.

Maps being redrawn, trucks being rerouted, telephones ringing continuously, and staff officers working with a single-minded intensity. The transformation that Patton initiated was not simply one of direction, but of spirit. Soldiers accustomed to fighting in one region were suddenly told to march toward an entirely different battlefield.

Tank crews were ordered to refuel and prepare for movement despite the bitter cold and slippery roads. Artillery units had to calculate new firing positions and coordinate with units they had not expected to support. The Third Army became a massive organism in motion, reconfiguring itself in real time.

One of the most remarkable aspects of the maneuver was the logistical coordination required. Patton understood that even the boldest operational concept was worthless without the material capacity to execute it. Fuel, ammunition, spare parts, medical units, and engineering detachments had to be positioned along the new route. The army’s movement was complicated by the fact that roads in northeastern France and Luxembourg were narrow, icy, and congested with retreating units and civilian refugees.

Yet, Patton insisted on maintaining speed above all else. He issued an order that captured his entire operational philosophy. Keep moving. Do not stop for anything unless you are fired upon and even then keep moving. This uncompromising demand for momentum was central to Patton’s style of war. He believed that speed was a weapon, a psychological force that could overwhelm the enemy before they could adjust their defenses.

In the Arden, this speed was not merely desirable, it was essential. The Germans had committed an enormous concentration of armored forces, and their success depended on maintaining the initiative. Patton knew that if he could shift the Third Army rapidly and strike hard, he could disrupt the German timetable, relieve Baston, and prevent the offensive from widening.

The stakes could not have been higher. Meanwhile, at Eisenhower’s headquarters, the mood had shifted from shock to determination. Eisenhower had placed tremendous trust in Patton, and now the entire Allied strategy hinged on whether the Third Army could deliver. Eisenhower’s staff began issuing priority directives to clear routes for Patton’s divisions.

Traffic control units were sent out to redirect convoys. Military police were deployed to manage intersections and supply depots were instructed to prepare for immediate redistribution of material. Eisenhower understood something that many of his critics had missed. He was not simply a coordinator of armies, but a manager of vast systems.

Ensuring that Patton’s maneuver succeeded required the cooperation of thousands of personnel across multiple commands. Even with such support, the difficulties facing Patton’s army were immense. Weather conditions were brutal. The winter of 1944 to 1945 was among the coldest in decades. Temperatures plunged well below freezing, snow fell heavily, and icy winds whipped across the roads.

Soldiers found their weapons stiffening, engines refusing to start, and vehicles sliding off icy surfaces. Many men marched through kneedeep snow with inadequate winter gear. their breath freezing in the air as they pushed themselves forward. Despite these challenges, eyewitness accounts consistently described the morale of the Third Army as unusually high.

Patton’s men believed in their commander. They had seen him accomplish the extraordinary before, and they were confident he could do it again. As the columns of tanks, infantry, and support vehicles moved relentlessly northward, Patton remained in constant communication with his subordinate commanders.

He demanded precise updates, issued direct instructions, and maintained an intense personal oversight of the operation. He visited units in person whenever possible, driving along frozen roads in his command jeep, accompanied by his staff and security detail. Soldiers frequently reported seeing Patton standing upright in his vehicle, binoculars in hand, scanning the horizon with an expression of fierce determination.

His presence energized the troops. One infantryman later recalled, “When Patton came through, it felt like we could take on the whole German army.” While Patton drove his army forward, the situation inside Baston grew increasingly desperate. The Germans continued to assault the perimeter, probing for weaknesses. The defenders, though resolute, could not hold indefinitely.

Brigadier General Anthony McAuliffe, acting commander of the 101st Airborne, famously responded nuts to a German demand for surrender. But the defiant spirit of the defenders could not compensate for dwindling supplies. Ammunition shortages became critical, especially for artillery units that played a crucial role in repelling German attacks.

Medical stations were overwhelmed and the wounded suffered in freezing conditions. Every hour counted. Patton’s gamble was that he could break through to Baston before the Germans overwhelmed the town. This meant pushing his divisions at a relentless pace. On December 21st and 22nd, the first contact between Patton’s forces and the northern roads of Luxembourg occurred, signaling that the Third Army had successfully completed the 90° pivot.

Combat units began engaging German forces almost immediately, catching many of them offguard. The speed of Patton’s movement had exceeded German expectations. Enemy commanders were still adjusting their defenses, unaware that a major American army was heading directly toward them. Patton’s leading divisions, primarily the fourth armored division, experienced fierce fighting, but the momentum was on their side.

Every mile they advanced brought them closer to Baston, and every hour they gained increased the likelihood of breaking the siege. The pressure on German forces intensified as Patton’s attack disrupted their timetable and diverted resources from the push toward the Moose River. Eisenhower, receiving constant updates, recognized that Patton’s gamble was succeeding.

The transformation of a potentially disastrous German breakthrough into an opportunity for a decisive Allied counter-strike was underway. Eisenhower’s earlier confidence in Patton now appeared prophetic. The Supreme Commander knew that the success of the Arden campaign would not be determined solely by the number of divisions committed, but by the ability of one army to accomplish a task that had seemed only days earlier operationally impossible.

By Christmas Eve, Patton’s forces were fighting their way within striking distance of the encircled town. The combination of speed, aggression, and unwavering determination that characterized the Third Army had placed them on the cusp of achieving one of the most celebrated relief operations in military history. The stage was set for the dramatic events of December 26th, when the first elements of Patton’s divisions would reach Baston and shatter the German encirclement.

By the morning of December 25th, 1944, the situation on the ground had evolved into a tense race between exhaustion and determination. Patton’s tanks and infantry were pushing through a labyrinth of icy roads, forested ridges, and entrenched German positions. The enemy, realizing that a major American force had arrived on their southern flank, began to react with increasing desperation.

German commanders diverted units intended for the western drive toward the Muse River and instead redeployed them to block Patton’s advance. They understood that if the third army reached Baston, the encirclement would collapse and the strategic momentum of the entire offensive would be lost. Every hour became a contest of pressure, attrition, and raw will.

Patton, however, refused to slow the pace. He pressed his commanders relentlessly, urging them to maintain constant pressure on the enemy. He emphasized that the rescue of Baston was not a symbolic objective, but a strategic imperative. If Baston held, the German offensive would fracture. If it fell, the Germans might regain the initiative and extend the war far beyond the already costly winter.

Patton’s sense of urgency was reflected in his famous Christmas prayer ordered only days earlier, asking that the weather clear so the Third Army could support the advance with air power. The prayer itself has become legendary, not only for its audacity, but because the weather did in fact clear shortly thereafter, allowing Allied aircraft to return to the skies and provide crucial support.

On December 26th, the decisive moment arrived. After days of fierce combat, the lead elements of the US 4th Armored Division broke through German lines and advanced toward the southern edge of Bastau. At approximately 1650, a small patrol led by Lieutenant Charles Boggas of Company C, 37th Tank Battalion, made contact with the defenders of the 101st Airborne Division.

The linkup was modest in scale, just a handful of tanks and infantrymen meeting at the edge of the town, but its symbolic weight was immense. The siege of Baston had been broken. The defenders, who had endured bombs, artillery bargages, freezing temperatures, and dwindling supplies were now connected once again to the larger Allied force.

When news of the breakthrough reached Patton, he responded not with celebration, but with a calm acknowledgement of duty fulfilled. He reportedly remarked, “A man must do his best.” A characteristic understatement from a commander known for both bold words and bold deeds. Patton understood that although the initial relief had succeeded, the battle was far from over.

The Germans still occupied strong positions around Baston, and the Third Army would need to widen the corridor, secure the supply routes, and push the enemy back to prevent another encirclement. The fighting would continue for weeks, but the psychological turning point had been achieved. The German offensive had been blunted, and the initiative was returning decisively to the Allies.

Back at Eisenhower’s headquarters, the reaction was one of immense relief and validation. Eisenhower had taken a calculated risk by placing his trust in Patton’s ability to maneuver his army with unprecedented speed. Many staff officers had doubted the feasibility of such a maneuver. Some quietly feared that Patton’s confidence might exceed logistical reality.

Yet the results were undeniable. Patton’s third army had turned 90°, marched through brutal winter conditions, engaged German forces on the move, and reached Baston in roughly the time frame he had promised at Verdon. Eisenhower’s earlier remark, “If anyone can do it, Patton can,” now stood as a testament to his understanding of Patton’s unique capabilities.

Eisenhower’s internal assessments of patent during this period, documented in later recollections and staff diaries, reveal a genuine admiration for the general’s operational clarity and willingness to embrace bold solutions. Eisenhower knew that in moments of crisis, conventional thinking was insufficient. What he needed was a commander capable of acting decisively under pressure, one who could mobilize an entire army with speed and coherence.

Patton had proven once again that he possessed that rare combination of intuition, preparation, and audacity. Eisenhower later reflected that Patton’s maneuver was one of the most brilliant operations of the war, a view shared by numerous military historians. Meanwhile, the German high command was experiencing growing disillusionment.

The failure to capture Baston in the arrival of Patton’s forces disrupted their operational timetable. Fuel shortages, logistical difficulties, and constant pressure from both north and south eroded the effectiveness of their units. The powerful armored thrust that had initially overwhelmed American positions were now bogged down by stubborn Allied resistance and counterattacks.

Hitler’s grand plan to split the Allied armies and force a negotiated peace was unraveling. The Allies regained control of key road networks, enabling them to resume coordinated operations across the front. For Patton, the relief of Baston marked not merely a tactical success, but the fulfillment of a commander’s responsibility.

He had long believed that a general must anticipate the enemy’s actions and prepare accordingly. His preemptive planning, executed weeks before the offensive began, had allowed him to respond with unparalleled speed. His leadership, characterized by personal presence, constant oversight, and insistence on aggressive action, galvanized his troops.

The Third Army had transformed what could have been a catastrophic defeat into a strategic opportunity. The psychological impact of Patton’s actions extended beyond the battlefield. Among Allied troops, his rapid pivot became a symbol of American resilience and determination. Soldiers who had felt isolated and overwhelmed by the German offensive suddenly realized that they were part of an army capable of swift and decisive action.

The legend of Patton, already formidable, grew even larger. His ability to impose his will on both his own forces and the enemy became part of the mythology of the European campaign. The implications of the relief of Baston for the broader war were profound. The German offensive soon stalled, exhausted by logistical shortages and unrelenting Allied counterattacks.

By January 1945, the Allies had regained nearly all the territory lost during the initial German advance. The failure of the Arden offensive depleted Germany’s last reserves of men, fuel, and armored vehicles. In a very real sense, Hitler’s final gamble in the West had ended not merely in defeat, but in strategic collapse. The path toward the Rine and ultimately toward the heart of Germany lay open.

Eisenhower later acknowledged that Patton’s actions were instrumental in turning the tide. He noted that the ability of an army to pivot so dramatically and forcefully was unprecedented in modern warfare. Eisenhower also recognized that Patton’s confidence had bolstered Allied morale at a moment when pessimism might have taken root.

The Supreme Commander, known for his calm and measured demeanor, was not prone to exaggeration, making his praise all the more meaningful. To his staff, he remarked, “Patton’s maneuver was a masterpiece. It altered the course of the battle and perhaps the war.” Looking back, historians view the 90deree turn of the Third Army as a case study in operational art.

It demonstrated how preparation, command discipline, logistical efficiency, and audacious leadership can combine to achieve the extraordinary. Patton’s actions were not mere instinct or improvisation. They were the product of a lifetime devoted to the study of war. His deep understanding of mobility, momentum, and the psychological dimensions of combat allowed him to see opportunities where others saw only obstacles.

The moment when Eisenhower asked Patton how soon he could attack, and Patton replied without hesitation, 48 hours, lives on as one of the defining exchanges of World War II. It encapsulates the relationship between two very different but complimentary leaders. Eisenhower, the strategic manager of vast coalitions, and Patton, the relentless warrior whose speed and daring made possible the relief of Baston.

The trust Eisenhower placed in Patton and the results that followed stand as testimony to the power of decisive leadership in times of crisis. The relief of Baston remains one of the most iconic achievements of the Allied campaign in Europe. It symbolizes endurance, sacrifice, and the capacity for bold action under the most severe conditions.

And at the center of that story stands George S. Patton, whose ability to turn an entire army in the midst of winter and deliver it to the gates of a besieged town within 48 hours continues to be studied, admired, and celebrated. It was this extraordinary act of military brilliance that prompted Eisenhower to tell his staff something that history has never forgotten.

If anyone could accomplish the impossible, it was Patton.

News

CH2 Japan Never Expected B-25 Eight-Gun Noses To Saw Ships Apart

Japan Never Expected B-25 Eight-Gun Noses To Saw Ships Apart Bismarck Sea, March 3rd, 1943. At precisely 0600 hours,…

CH2 Japanese Admirals Never Knew Iowa’s 16 Inch Guns Could Hit From 23 Miles- Until They Had To Learn The Lesson Paid With 4 Of Their Ships

Japanese Admirals Never Knew Iowa’s 16 Inch Guns Could Hit From 23 Miles- Until They Had To Learn The Lesson…

CH2 How One Mechanic’s “Illegal” Engine Trick Made Mosquito Bombers Outrun Every German Fighter

How One Mechanic’s “Illegal” Engine Trick Made Mosquito Bombers Outrun Every German Fighter The De Havilland Mosquito shouldn’t have worked….

CH2 When a 72-Hour Retreat Turned Into a 300-Mile Counterattack That Germany Never Believed Possible

When a 72-Hour Retreat Turned Into a 300-Mile Counterattack That Germany Never Believed Possible At dawn on February 20th, 1943,…

CH2 The Army Tried to Kick Him Out 8 Times — Until He Defeated 700 German Troops with Just 35 Men

The Army Tried to Kick Him Out 8 Times — Until He Defeated 700 German Troops with Just 35 Men…

CH2 How One Farmhand’s “STUPID” Rope Trick Destroyed 35 Zeros in Just 3 Weeks

How One Farmhand’s “STUPID” Rope Trick Destroyed 35 Zeros in Just 3 Weeks May 7th, 1943. Dawn light seeped…

End of content

No more pages to load