Wehrmacht Major Fled the Eastern Front — 79 Years Later, His Buried Field Chest Was Found in Poland

It was the kind of forest that swallowed sound. A vast stretch of pine and birch, thick with moss and silence, just a few kilometers off any mapped road near the Białowieża forest. The air was cool and heavy with the scent of iron and rain-soaked earth. If you listened long enough, you could hear water dripping from the branches, but little else. No traffic. No distant hum of tractors. Just stillness.

Two hobbyist metal detectorists from the nearby town of Hajnówka had walked into that silence one gray afternoon, searching for remnants of the past—spent shell casings, rusted helmets, maybe even the occasional lost relic from the war that had once consumed these woods. To them, the forest was less a place of mystery than a familiar friend, one that hid old stories under every root. They moved methodically, their detectors sweeping side to side over the damp soil, the steady rhythm broken only by the soft beeps that occasionally hinted at buried metal.

The first signal was faint, inconsistent—so much so that they almost ignored it. In this region, the ground was littered with debris from decades of conflict. Old shrapnel, broken tools, tractor parts, even Soviet fuel drums—it was impossible to dig without finding traces of someone else’s war. But this sound was different. The frequency was deep, dense, not the erratic chirp of a small object. They exchanged a look. Then, with quiet agreement, they began to dig.

At first, the shovels scraped against roots and stones, the soil dark and thick with moisture. But then came the metallic thud—solid, unyielding. They dug faster, careful but driven by curiosity. An hour later, after clearing away layers of packed clay and tangled undergrowth, they found it: the edge of something square and ironbound.

It was larger than a munitions crate and heavier than any field locker they had unearthed before. The corners were reinforced with riveted steel, and the surface bore the faint, corroded outline of an emblem—an eagle, its wings outstretched, the details almost erased by rust. The men stopped. One muttered a nervous joke about hidden treasure, about N@zi gold. The other didn’t answer. The chest was too old, too heavy, too deliberately buried for coincidence.

It took both of them, straining, to lift it from the earth. The box came free with a reluctant groan, the kind of sound that seemed to echo deeper than the forest itself. Dirt clung to the seams like dried blood. They set it down on a tarp, their breaths visible in the cold air. The metal was cold to the touch, even through gloves. It hadn’t seen daylight in decades.

When the first latch broke free, the hinges screamed like something alive. The chest exhaled the stale, dry air of another century. What lay inside wasn’t gold. It wasn’t weapons. It was something stranger, more intimate—a perfectly preserved military uniform, folded beneath an oiled canvas, its gray-green wool still sharp after seventy-nine years. The silver piping along the shoulder boards gleamed faintly in the dim light. The rank insignia left no doubt: a major of the Wehrmacht.

For a moment, the men simply stared. This wasn’t junk or battlefield debris. This was a time capsule. Someone had buried it deliberately, carefully, almost reverently. Beneath the tunic lay documents—faded but legible—maps annotated in neat red circles, letters written in looping cursive, a leather holster containing a Luger pistol, its magazine still full. Everything was organized, folded, and sealed against time, as if whoever had packed it knew it might be opened again someday.

One of the men picked up the tunic, shaking off loose dirt. The stitching was perfect. On the breast pocket sat a ribbon bar with campaign medals, and below it, the unmistakable iron cross. It was the uniform of an officer who had seen combat, who had lived through years of war. The air around them felt heavier.

They kept going. Beneath the maps, they found something wrapped in oilcloth—a small black leather journal, its pages bound shut with a brass clasp. The cover was cracked, the binding frayed, but still intact. One man whispered, “This belonged to someone important.” He wasn’t wrong. In that moment, the forest seemed to close in, the trees watching in silent witness as they uncovered not treasure, but a life sealed in metal and memory.

They found identification next. A small metal tag, worn but legible. Albert Erich. Major. 9th Army. That was when the reality of it sank in. This wasn’t just a relic—it was a grave without a body. A man’s life, packed into a box and buried deep enough to be forgotten.

The name sent ripples far beyond the forest. When local authorities were alerted, a team from Białystok arrived before sunset. The chest was cordoned off, photographed, and cataloged under strict procedures. Forensic specialists moved carefully, their gloves brushing away layers of soil as if touching something sacred. The field chest was transported intact to a secure facility, while the journal—now considered a potential historical document—was sent to Warsaw under armed escort.

In towns like Hajnówka, rumors spread faster than facts. Some said the box contained stolen treasure, others claimed it held coded war plans, or evidence of espionage. But what everyone agreed on was that it was deliberate. Whoever Major Erich had been, he had not lost this chest by accident. He had buried it himself.

The discovery reached Warsaw within days. The name “Major Albert Erich” surfaced in German archives and Polish military records. Historians began to dig through microfilm and faded documents, searching for the man behind the uniform. It turned out he had existed not as a myth, but as a real and traceable figure—a mid-level Wehrmacht officer who had simply vanished in the summer of 1944. No record of death. No capture. No confirmed defection. Just silence.

Archival research painted a picture both ordinary and extraordinary. Born in 1908 in Lübeck, Erich had joined the German army long before the war, part of the professional officer corps that had served through the interwar years. His early personnel records described him as disciplined, methodical, and ambitious. By 1941, when Operation Barbarossa launched the invasion of the Soviet Union, he was serving on the Eastern Front with the 9th Army under Army Group Center—a position that carried immense responsibility and moral weight.

His orders placed him in Belarus, a region that had become one of the war’s most brutal frontlines. Official documents recorded him as a “field logistics coordinator,” but anyone familiar with the language of military bureaucracy knew what that meant. It wasn’t just about supplies. It was about control, discipline, and compliance. The Eastern Front demanded obedience to a system that blurred the line between warfare and ideology.

From 1942 to 1943, Erich’s name appeared on requisition lists, clearance orders, and transport reports—dry paperwork that hid grim realities. His superiors praised him for efficiency, precision, and unwavering loyalty. He was promoted to major before the end of 1943, cited for “exemplary conduct in maintaining operational discipline.” But between the lines, another story began to surface.

Letters recovered from private correspondence described subtle changes in tone—an officer growing disillusioned, a man beginning to doubt the war he was fighting. One fellow officer wrote to a colleague in Berlin, describing Major Erich as “an ice-faced loyalist cracking from within.” Another report mentioned “growing tension between Erich and party officers over the treatment of civilians.”

By early 1944, he had been reassigned from front-line duty to a logistics command near Baranovichi. Officially, the reason was “strategic reorganization.” Unofficially, it was punishment. He had questioned too much, spoken too openly.

And then, in June 1944, as the Soviet counteroffensive known as Operation Bagration began, the paper trail ended. His last recorded appearance was a supply ledger entry in Brest-Litovsk on June 30. After that, nothing. No report of his death. No transfer. No disciplinary record. His name simply disappeared from the rolls.

For nearly eighty years, that was where the story stopped. Until now.

The chest buried in the Polish forest suggested something more—a man who didn’t die in battle, who didn’t defect, but who instead made a choice. Somewhere in those final days, as the Red Army advanced and the German front collapsed, Major Albert Erich buried his uniform, his maps, his letters, and his journal in a steel chest deep in the woods.

Whatever compelled him to do so—fear, guilt, or the need to leave behind a testimony—remained locked inside that tarnished brass clasp. And after seventy-nine years underground, the forest had given it back.

As local historians and military archivists began to piece together fragments of his life, one question hung heavy over the discovery. Why had he run? Why had he chosen to bury his identity rather than destroy it?

Somewhere in that black leather journal, sealed for nearly eight decades, the answer was waiting. But for now, all anyone could say for certain was that the forest had spoken again—and the story of Major Albert Erich, the officer who vanished from the Eastern Front, was only beginning to rise from the soil of Poland.

Continue below

It was the sort of place you’d expect to find old bottles or rusted farm tools quiet pine covered a few kilometers off any marked trail near the Białowieża forest. Dense undergrowth choked the path and the air smelled faintly of wet moss and iron.

For two hobbyist metal detectorists from Hajnovka, it was just another weekend scan, a chance to escape the noise of the world and chase whispers from the past. The beeping started faint and inconsistent, but it grew louder with each sweep. At first, they assumed it was just scrap, maybe a leftover Soviet casing or a broken tractor part. But when the shovel hit metal and kept hitting it, the tone changed. They uncovered the edge of something square, thick, and stubborn.

It took an hour of digging, clearing away layers of clay packed soil and half-rotted roots before the box finally revealed itself an old military field chest reinforced with riveted iron and sealed tight with two corroded latches. The men exchanged a glance. One muttered a nervous joke about Nazi gold. The other didn’t laugh.

The chest was too well preserved, too heavy, and buried too deep for it to have been casually discarded. They hoisted it out with effort, dirt crumbling off the sides like dried blood, and laid it down on a tarp. A stamped emblem on the top, barely visible through the rust, showed the faint outline of a overmatched eagle.

The latches gave with a groan that echoed like a warning. Inside wasn’t treasure. Not exactly, not in the way they expected. The chest exhaled the stale breath of nearly eight decades. Beneath a layer of oiled canvas lay a neatly folded gray green officer’s tunic. The silver piping of a major still gleaming, untouched by time. The metal detectorists froze. This wasn’t scrap. This was a time capsule.

There were papers faded but legible, a sidearm, old maps inked with strange red circles, and at the bottom, wrapped in oil skin, a journal bound in black leather and sealed shut with a brass clasp. One man whispered, “This belonged to someone important.” He was right. What they’d found wasn’t just relics.

It was a confession buried beneath decades of silence, waiting to speak again. The forest around them held its breath. Nothing moved. Not the wind, not the birds, just the creek of leather and the rustle of old fabric as the contents of the chest were slowly, carefully laid out across the tarp. The vermocked tunic came first stone gray wool, still sharp in its lines, with shoulder boards bearing a golden pip and white underlay, major rank.

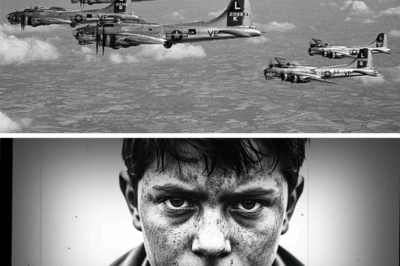

Below the left breast pocket, a ribbon bar with two campaign medals and one unmistakable iron cross. The chest plate was heavy with more than insignia. It carried the weight of memory. Beneath the uniform, a sidearm in its holster, a Luger P8, pristine, its magazine still full. There were folded maps, German military issue, each annotated in a tidy hand, red circles, arrows. Several were stamped her group Amida, the Eastern Front.

Tucked beside them, personal letters written in a looping script, some stained with time, others still crisp, as if never read. A small envelope addressed a minor mutter lay unopened. None of the contents were haphazard. Everything had been placed deliberately, almost reverently, like someone preparing for a burial. Then came the ID tags.

Albert Erish Maj 9 Army. It was suddenly real. This wasn’t just a soldier’s effects. This was a name, a rank, a life. Major Eric Alrich, a man who by every record available had vanished without trace in the summer of 1,944 as the Eastern Front collapsed and the Soviet advance tore across Bellarus and eastern Poland.

No official record of death, no confirmed defection, just silence. The sealed journal remained untouched, its pages still bound by a tarnished clasp. Its leather was dry, cracked in places, but intact. Local authorities were contacted immediately. Within hours, a forensic team arrived from Bawa Stock, and the chest’s contents were carefully cataloged and removed.

The field chest, still intact, was loaded into a secure container. The journal, potentially explosive in its implications, was sent to Warsaw under armed escort. Whispers spread fast in towns like Hajnovka. Some said it was looted treasure. Others claimed the man had been a spy. But no one really knew what they were dealing with yet.

What was clear was this. Whatever had happened in the final days of Major Alrech’s war. It hadn’t been an accident. He buried that chest for a reason. And now, after 79 years underground, his secrets were finally rising to the surface. Before the name Major Eric Alrech was found inside a decaying chest beneath the Polish woods, it lived buried in brittle archives across Europe, scattered through German war logs, Red Army intelligence files, and the fading rosters of a crumbling rush. In the weeks following the discovery, researchers at the Central Archives of Modern Records in Warsaw and

the Bundis Archive in Berlin pieced together fragments of a military career forged in the early firestorms of Operation Barbar Roa. Alrech’s personnel file marked him as an early volunteer, enlisting in 1935, long before the war began. By 1941, he was on the Eastern Front, a hopman with the 9inth Army under Army Group Center, tasked with maintaining order in occupied Bellarus, an assignment that in Nazi terminology meant more than just strategy. It meant executions, logistics, and ideology. Reports from 1,942 to 1,943 list him as a capable officer praised for discipline, precision, and loyalty to national socialist values. His signature appears on requisition orders, town clearances, even directives involving the relocation of partisans euphemisms used by Vermacht and SS alike. He was rewarded with fast promotions, climbing to the rank of major by late 1943.

But something shifted during the brutal winter of that year. Letters from fellow officers mention Alrech growing increasingly isolated, critical of Berlin’s empty rhetoric and troubled by civilian deaths. One referred to him privately as an ice-faced loyalist cracking from within.

In early 1944, records place him at a field HQ near Baranovichi, Bellarus. But by June, as Soviet armor began to push west in the opening salvos of Operation Bagration, he was reassigned to a rear logistics position outside Warsaw officially due to strategic restructuring. Though unofficial notes suggest disciplinary friction, Alrech was no longer the rising star.

He was a decorated officer being moved out of sight. His final official appearance in Vermach records comes from a June 30 supply ledger in breast leavsk. After that, nothing. No court marshal, no death report, no confirmed sighting. The German war machine, which documented everything, simply lost him. It was as if Major Alrech stepped off the map in the middle of a war and never came back.

By the summer of 1,944, the Eastern Front wasn’t retreating. It was imploding. Operation Bagrashan, launched by Soviet forces in late June, was more than a counteroffensive. It was a strategic annihilation. Entire German divisions vanished in the forests of Bellarus, swallowed by a storm of artillery, tanks, and endless waves of red infantry. Supply lines crumbled. Communications fell silent.

The roads choked with vehicles, horses, and the dead. For many Vermached officers, the question was no longer how to hold ground. It was how to survive long enough to flee. Alrech’s unit, a logistical detachment based near Breast Letovsk, was caught in the path of the Soviet first Bellarussian front as it surged across the Bug River. What followed wasn’t battle. It was slaughter.

Eyewitness reports from surviving German troops describe roads lined with destroyed convoys, makeshift graves, and abandoned weapons. Officers once loyal to the Reich were now deserting in pairs, disguising themselves as peasants, torching their uniforms in the dark. It was during this chaos, somewhere between June 30 and July 5, that Major Eric Alrech vanished.

No confirmed sighting, no message to command, just gone. His absence was noted in a July 7 field report. Major Alrech unaccounted for since crossing to fallback position near Wodawa. There were no orders issued in his name after that date. And in a crumbling army obsessed with paperwork, that silence said everything.

What remained of Army Group Center continued its retreat, but the damage was done. More than 200,000 German troops were lost in a matter of weeks. Commanders were executed for cowardice. Others disappeared like Alrech, swallowed by the smoke of their collapsing world. Some ran east, hoping to surrender to Soviet units. Others headed west, praying to reach German lines.

A few tried to disappear entirely. Months later, in the ruins of Warsaw, Soviet intelligence found scraps, abandoned field files, a torn off page from an officer’s diary. One line stood out. Alrech spoke of ending it in the forest, said the Reich was dead, said he would bury it. The Red Army dismissed it as nonsense, the ravings of a broken man.

But 79 years later, in a forest not far from where those last lines were written, a chest was unearthed, and inside it the truth began to whisper. It took forensic archavists nearly 2 days to unseal the journal. The leather had dried into stiffness, and the brass clasp refused to budge until warmed by gentle heat and pried loose with a wooden tool. Inside, the ink had survived surprisingly well.

The entries began in the clipped precision of a disciplined mind. Supply lists, regiment movements, dates, and maps. But as the pages turned, the handwriting loosened, grammar bent. The orderly lines gave way to bursts of emotion, marginal notes, corrections scratched out so hard the page tore. What emerged wasn’t a report. It was a confession.

The earliest entries were cold mechanical. Alrech documented fuel shortages, troop morale, orders from command. But by late June 1944, just days after the Soviet breakout, the tone shifted. Bagration is worse than Stalinrad, he wrote. We are not fighting. We are fleeing. Orders are chaos disguised as command. His anger simmered under the surface.

One line was underlined twice. No air cover, no reinforcements, no answers. By mid July, paranoia crept in. Are they watching me? Has someone read the letters? Another passage. I was followed last night. Or I imagined it. The line is thinning, my mind cracking. He wrote of dreams, blizzards, firestorms, a forest that swallowed whole battalions.

Then guilt references to cleansing operations in Bellarus. Entire villages reduced for security. Orders signed by him that he now called errors in judgment. Crimes if history dares to name them. The final entry was dated the 13th of August, 1944. The words were slower, each line more deliberate, almost ceremonial.

I no longer serve the right. I bury what I was. Let history forget me. He mentioned the chest by name, this box of ghosts, and described its burial under the third pine west of the broken path, precisely where it was found. There were no goodbyes, no full name, just his rank scratched out beneath the last sentence, as if he no longer wanted it. The journal closed like a door swinging shut on a life.

And in that silence, one thing was certain. Major Eric Alrech had not died in battle. He had erased himself or tried to, but the Earth remembered what he wanted buried. After the war, when the shooting stopped, but the questions didn’t, names began to surface. Fragmented, whispered, scratched in margins of Soviet doss and Allied interrogation transcripts.

One of those names was Alrech. Not always first, never confirmed, but there beneath layers of confusion, fear, and silence. A German major with knowledge of army group center withdrawal logistics, last seen in eastern Poland. In some accounts, he was fleeing east. In others, west, always alone, always vanishing.

A 1,947 interrogation in Lublin of a captured Vermached quartermaster mentioned a staff officer who disappeared with maps and cipher books. Another file, this one British, declassified decades later, spoke of a man matching Alrech’s profile, trying to trade sensitive troop movement data to Soviet intermediaries in exchange for safe passage or ideological asylum. No names, no deal confirmed.

But one phrase stuck. Too clean for a deserter, too frightened for a spy. Among Polish partisans, stories circulated about a German officer who’ turned himself in with forged papers and a warning of purges coming to villages thought to be aiding resistance. Some say he was allowed to leave in exchange for information.

Others believe he was executed in the forest and left where no one would find him. Both versions end the same way. A body that was never recovered. A face no one quite remembered. In the East German files that survived the fall of the Berlin Wall, one scrap stood out. a Stazzi memo referencing Operation Heimcare, a 1,952nd surveillance program targeting ex-Nazi officers rumored to be living under false identities.

One target, unnamed, was said to have been a former major of the 9inth Army, likely presumed dead in Poland, last known to possess knowledge of compromised supply routes. The memo ends with a chilling line. If found alive, retrieve or silence. Hope text two. Hope text two. The theories bloomed like rot in damp earth.

That Alrech was a traitor, a double agent, a man who tried to trade one uniform for another and failed. Or worse, he was neither spy nor coward, just a soldier who saw the truth too late and broke beneath its weight. And yet no rumor ever explained the chest or the journal or why, if he’d run to save himself, he buried the only proof he existed.

It wasn’t until the field chest was fully disassembled for conservation that one last compartment revealed itself. A warped wooden panel at the bottom, warped from years of moisture, came loose under pressure. Behind it, tucked in a narrow cavity lined with tar paper, was a final bundle wrapped in oil cloth. The contents made everyone pause.

Inside, a red and white armband bearing the anchor symbol of the Ara Kraoa, the Polish home army. Next to it, identification documents printed in pre-war Polish and stamped with forgeries that almost passed inspection. The name on the papers wasn’t Eric Alrech. It was Yan Kowalsski, a catch-all alias so common it was almost a joke. But the photo, blurred and water stained, was unmistakably him.

The implications were staggering. Alrech, the Vermach major, the man with medals and battlefield honors, had either infiltrated the Polish resistance or joined it. Historians debated the find with cautious intensity. The armband was authentic. The paper used in the forged documents matched 1,942 Polish stock and handwriting analysis suggested the Polish signature halting uneven was Alre’s but the why remained elusive.

Was it a desperate survival ploy, a disguise to avoid Soviet capture? Or something deeper? Eyewitness accounts from aging home army survivors hinted at a German defector who appeared in the forests near Bowawia in the late summer of 1,944. He spoke Polish poorly but offered us maps. One recalled said he had information. Said he was done killing. No names were recorded, no photos taken, just a memory half swallowed by time.

The idea of a vermocked officer seeking refuge among the very people his army had tried to destroy strained belief, but the chest didn’t lie. The armband was folded with care. The false papers weren’t thrown in. They were hidden, protected. Alrech hadn’t abandoned these objects in haste. He’d preserved them.

Like a man preserving the version of himself he hoped would outlast the war. Whatever role he played, informant, sympathizer, infiltrator, one thing had become clear. The story of Eric Alrech didn’t end in uniform. Somewhere along the line, something cracked. And through that crack, the truth had begun to seep out.

Less than half a kilometer from where Alrech’s chest was unearthed, a pair of amateur military historians scouring the same stretch of pine forest made a second discovery. This one colder and far older. At first they thought it was just a depression in the ground. A sunken patch lined with old pine needles and rotting leaves, but the soil gave way easily. Too easily just below the surface bone.

Then another, then the remnants of a boot soul. They stopped digging and called it in. Within 24 hours, forensic teams confirmed the site held four skeletons hastily buried and partially preserved by the acidic forest soil. Militaryissue buttons and fragments of feld grow wool confirmed the remains belonged to German soldiers.

Nearby, a rusted mouser rifle and empty cartridge casings hinted at execution rather than battle. Two skulls bore entry wounds to the back of the head. One still had a crushed helmet on. None of them had identification tags. The proximity to Alrech’s chest raised immediate questions.

Who were these men? What were they doing here? And most urgently had they died at Soviet hands, partisan ambush, or something far more personal. Polish resistance records from the area mentioned several skirmishes in July and August 1,944, including one ambush of a four-man Vermached patrol. But the date didn’t quite align.

Another theory surfaced darker that these men had discovered Alrech’s desertion, that they’d tried to stop him, or worse, were loyalists he’d led into the woods before turning on them. In Alrech’s journal, one entry stood out. Four follow me now. One suspects. I must act before they speak. No names, no locations, just that.

If the bodies were his men killed to protect his defection, then Alrech hadn’t just walked away from the Reich. He had crossed a line he could never return from. if they were partisans in disguise or Soviet scouts caught and executed. The questions shifted again. But the silence of the dead refused to yield answers.

No personal effects, no dog tags. Just four unnamed soldiers left in a shallow grave as the war roared past and one field chest buried just beyond the treeine, watching, waiting. After the journal’s final entry, Eric Alrech vanished utterly, completely. No confirmed sighting, no official report, no letters, just a closing line and a buried chest.

Polish investigators supported by German archavists began digging into war era refugee records, passenger manifests, and dennazification files. What they found was a tangle of speculation, half-truths, and dead ends. It was as if Alrech had stepped into the trees in 1944 and simply dissolved. Attempts to trace surviving relatives offered no clarity.

A niece in Leipzig insisted her uncle had died in a Soviet internment camp sometime before 1950, though she admitted she had never seen a body or received confirmation. Only a letter from someone who claimed to be a friend of Eric’s. Meanwhile, another relative in Dusseldorf told a vastly different story. According to her late mother, Alrech’s sister, he had escaped through Czechoslovakia after the war and eventually boarded a ship from Genoa in 1947 bound for South America. Argentina, she said he started over there.

She used to get postcards, always unsigned. Searches through immigration files turned up possibilities, but no matches. and E Alrech did arrive in Buenosire aboard the SS Giovana Sea in late 1947, but the age didn’t line up and the manifest listed him as a mechanic, not an officer.

In postwar Poland, an unmarked grave near Gdinsk contained the remains of a man buried under the name John Kowalsski, the same alias found in the field chest. The headstone was simple. No dates, no family, no cross. Exumation was considered, but without definitive DNA from surviving relatives, the lead faded. There were other stories, too. A farmer near Augustin claimed he once fed a German who spoke perfect Polish and limped when he walked.

A Soviet vet swore he saw a German officer executed by partisans near Wombja, tied to a tree, and left for the crows. None could be verified. In the end, the trail split in every direction but led nowhere. Alrech became a ghost, a man who had once worn a uniform, then walked into the woods with a box full of secrets and was never seen again.

And maybe that was exactly what he wanted. The field chest never returned to the ground. After conservation and forensic review, it was placed in a glass case at the Podlaski War Memory Center in Bawisto, just a few hours from where it had been found. Visitors stop in front of it every day now, staring at the gray green uniform folded inside, the armband beneath the officer’s cap, and the journal encased in thick plexiglass like a religious artifact.

No audio guide plays, no plaques give conclusive answers, just a single inscription at the base. Found, not forgotten. But the arguments haven’t stopped. To some historians, the chest is a monument to cowardice, a reminder that Alrech, like many others, chose to run when the Reich collapsed rather than face justice or responsibility.

They cite the executions in the woods, the lack of testimony, the officer’s rank. He knew what he was part of. They argue he buried his sins, not his past. Others see something else. They point to the journal, the disillusionment, the forged papers, the fact that Alrech chose to vanish instead of cling to power.

They argue it wasn’t cowardice. It was renunciation. The field chest to them isn’t an escape pod. It’s a confession box. a man trying to bury a version of himself he no longer wanted to live with. Still, others treat the chest as a symbol of the war’s unanswerable questions. What makes a traitor? What makes a survivor? And is redemption possible when it arrives too late? School groups pass through the exhibit, their teachers guiding them past other displays, helmets, rifles, maps, bones, but the chest always draws the longest pause. Something about it feels different. less

like a weapon, more like a whisper. Every few months, letters arrive at the museum. Some from Germany, some from Poland, one from Buenoseries. All asking the same question. What really happened to Major Alrech? The museum never replies with certainty because there is none.

Just the silence of the woods, the creek of leather straps, the weight of a story once buried, now held behind glass, and the uneasy sense that sometimes history doesn’t give you answers. It just hands you a box and leaves you to decide what it means. In the final pages of Alrich’s journal, the tactical diagrams and daily logs gave way to something raw, something human. There were no orders, no ranks, no rhetoric.

Just the voice of a man peeling back the armor he’d worn too long. Entry by entry, the soldier who had once been praised for his unyielding loyalty to the Reich began to unravel his allegiance, not in grand declarations, but in quiet, personal reckoning. “I believed,” he wrote in one entry dated late July 1,944. “God help me.

I believed in order, in duty. I believed the world could be corrected through discipline. But I did not see where that line ended or where it began to rot. He spoke of villages turned to ash, of faces he could no longer remember, but whose screams still lived in his ears. “I followed orders,” he wrote.

Then I watched what following orders turned me into. Several pages later, one paragraph stood alone, written in a steadier hand. If silence is my inheritance, let it be silence earned in contrition, not cowardice. Esau soul. But perhaps the most heartbreaking find was not in the journal itself, but folded behind its back, cover a letter, never mailed, yellowed and delicate, it was addressed to mutter, written in the same looping script, but with none of the precision of his field reports. It began formally, then fell apart halfway through, the ink

darker where the pen pressed harder. I am not the son you raised. I do not expect forgiveness. I only hope you remember the child, not the uniform. I can no longer serve a cause that devours its own soul. I will not wear its symbols again. Tell Anna I’m sorry. Tell her I remember the lake.

The letter had no date, no return address, just his name at the bottom, hastily signed. It was never sent. Maybe he never meant to. Maybe it was just something he needed to write before he buried everything else. And so the chest became more than a military artifact. It was a container of conscience, a sealed reckoning, a war not just between nations, but within a single man.

Years from now, visitors to the Bawa Stock War Museum will still stop before the glass case containing the chest of Major Eric Alrech. They’ll peer at the Luger pistol, the armband, the faded documents. But what lingers isn’t the hardware of war. It’s the haunting absence of clarity. Because what the chest left behind wasn’t just artifacts. It was questions. Difficult ones.

The story of Alrech doesn’t fit neatly into the shelves of history books. He wasn’t a hero. He wasn’t condemned by tribunal. He didn’t die with honor or in disgrace. He simply disappeared. A man who wore the eagle then buried it. A name struck from rosters and swallowed by trees until the forest gave him back. His journal doesn’t scream ideology. It whispers erosion.

One belief cracking under weight, then collapsing under guilt. The field chest, neatly packed, hidden, sealed, wasn’t just an attempt to preserve. It was an attempt to let go. And yet, in trying to bury the truth, Alrech ensured it would one day be unearthed. There is no clear verdict. Was he trying to defect? Did he seek atonement or just escape? Were the bodies in the shallow grave enemies, witnesses, or fellow deserters? Did he live out his days under a false name, haunted and silent? Or did the forest claim him as it did so many? What we’re

left with is a single point in time, one man’s final act, frozen in rust and paper, and from that a prism of possibilities. Cowardice and conscience, shame and survival, guilt and grief. Historians still argue, visitors still speculate, and somewhere between the armband and the journal, between the orders and the apology, the truth flickers like a fading signal in static.

In the end, perhaps Alrech wasn’t trying to be remembered at all. Perhaps he wanted to be forgotten. But history has a way of reaching backward, of digging through earth and silence until even the quietest stories are forced to speak. So the question lingers like smoke. Was Major Eric Alrech a traitor, a survivor, or something in between? And the chest still locked behind glass offers no answer.

Only the weight of a man who tried to bury his past and the war that refused to let him. This story was brutal. But this story on the right hand side is even more insane.

News

CH2 Why German Infantry Feared the 101st Airborne More Than Any Other Division

Why German Infantry Feared the 101st Airborne More Than Any Other Division June 6th, 1944. 02:15 hours. Sainte-Mère-Église, Normandy….

CH2 How One Woman Exposed the Hidden Gun That Shot Down 28 Planes in 72 Hours at Iwo Jima

How One Woman Exposed the Hidden Gun That Shot Down 28 Planes in 72 Hours at Iwo Jima February…

CH2 The 96 Hour Nightmare That Destroyed Germany’s Elite Panzer Division

The 96 Hour Nightmare That Destroyed Germany’s Elite Panzer Division July 25th, 1944. 0850 hours. General Leutnant Fritz Berlin…

CH2 One Of Many Unsung Heroes – The 13-Year-Old Boy Who Guided Allied Bombers to Target Using Only a Flashlight on a Rooftop

One Of Many Unsung Heroes – The 13-Year-Old Boy Who Guided Allied Bombers to Target Using Only a Flashlight on…

CH2 June 4, 1942 At 10:30 AM: The Five Minutes That Destroyed Japan’s Chance Of Winning WW2

June 4, 1942 At 10:30 AM: The Five Minutes That Destroyed Japan’s Chance Of Winning WW2 June 4th, 1942,…

CH2 The Moment That Almost Changed History: Why Patton Wanted to Attack the Soviets in 1945 Revealed – The Warning Eisenhower Refused to Hear

The Moment That Almost Changed History: Why Patton Wanted to Attack the Soviets in 1945 Revealed – The Warning Eisenhower…

End of content

No more pages to load