They Said the Shot Was ‘Impossible’ — Until He Hit a German Tank 2.6 Miles Away

At 10:42 a.m. on December 1st, 1944, Lieutenant Alfred Rose climbed into the turret of his M36 Jackson tank destroyer and shut the hatch behind him. The metal clanged shut with a hollow finality, muffling the distant thunder of artillery and the sharp wind sweeping over the high ground northeast of Baesweiler, Germany. The air outside was cold and brittle, carrying with it the heavy smell of mud, cordite, and burnt fuel. He wiped his gloves on his jacket, smearing a streak of grease across the olive fabric, and stared down at the unfamiliar maze of levers, dials, and scopes in front of him. This was his first real command in the 814th Tank Destroyer Battalion—a baptism by fire, as everyone in his crew liked to call it. But this morning, Alfred Rose didn’t feel like a commander. He felt like a man sitting inside a machine he didn’t yet understand, facing an enemy that had made a science of killing.

He was twenty-six years old. Three weeks in the unit. Zero confirmed kills.

And somewhere two miles away, forty German Panther tanks were prowling the countryside, waiting to strike.

The M36 Jackson was supposed to be America’s answer to the Panther. The 90mm M3 main gun it carried could, on paper, punch through nearly six inches of armor at 1,500 yards—numbers that had thrilled the ordnance engineers who designed it and reassured the generals who approved its production. But paper meant nothing here in the Rhineland. Out here, equations turned to smoke and shattered steel. The men who’d come before Rose knew it too well. In the last month alone, his battalion had lost eleven tank destroyers—some reduced to smoldering wrecks, others vanishing in the explosions of their own ammunition racks. Seventeen men dead, some burned alive inside their vehicles before rescue crews could reach them. Rose had read the after-action reports late at night by flashlight, the smell of diesel and fear still in his nose. Every report began the same way: the Germans spotted them first, fired first, hit first. Every time.

The old M10 Wolverines, with their 3-inch guns, had been no match for the Panthers. At 800 yards, their shells would shatter or ricochet off the German tanks’ sloped frontal armor. To get close enough for a kill shot meant driving straight into the crosshairs of the 88mm gun—the most feared weapon on the European battlefield. The Wolverines were death traps, and every crewman in the battalion knew it. So when the new M36 Jacksons arrived in September, they were hailed as salvation. More power, better range, thicker armor. Yet for Rose, salvation felt strangely hollow when he sat inside one, his breath fogging the sight lenses as he tried to make sense of the controls.

The truth was brutal and simple: he had no idea what he was doing. He’d fired four training rounds through the gun back in England—on a practice range under perfect conditions, no wind, no return fire, no mud, no death waiting behind every tree line. He didn’t know the quirks of the M76F telescopic sight, didn’t know whether its reticle had been properly calibrated or if some overworked mechanic had made field modifications without recording them. The manual in his lap was smeared with grease, half unreadable, the diagrams confusing even to seasoned gunners. And yet, there he was, crouched in a steel box on the edge of a hill, expected to destroy enemy tanks with mathematical precision.

At 10:56, he adjusted the gun elevation, just to feel the mechanism. The wheels turned stiffly. His gloves slipped once on the cold metal. He took a deep breath and looked through the scope again. The glass was clear, the crosshairs sharp. Distance markers stretched across the reticle—400 yards, 800, 1,200, all the way up to 4,600 yards. The farthest marking seemed almost theoretical, like a joke for the range officers who’d never actually seen combat. Tank engagements rarely happened beyond 1,000 yards. At 2,000, your odds of hitting anything smaller than a barn door dropped to nearly zero. Beyond that, it wasn’t a battle anymore—it was an artillery problem.

But the Germans didn’t care about statistics. They had perfected their method. They knew the American range limits, the slope of their armor, the weak spots of the Jackson’s gun shield. The Panther was designed with cold logic: thick, sloped armor on the front to deflect shots, a long 75mm gun that could reach out farther than most Allied tanks, and an engine powerful enough to reposition quickly after firing. Against that, every American tank felt like an antique, every engagement a coin toss between survival and destruction. Rose’s commander, a grizzled major with a permanent squint, had told him bluntly, “Learn that gun fast, Lieutenant. The only thing between you and a hole in the ground is how quick you can find the range.”

Outside the turret, the wind picked up, carrying with it the distant rumble of engines. The countryside beyond Baesweiler stretched out in rolling fields, broken by tree lines and the occasional farmhouse reduced to rubble. Somewhere out there, German armor was moving. Intelligence reports said the 5th Panzer Army was regrouping for a counterattack, pushing west toward the Siegfried Line. Rose’s battalion had been ordered to cover the northeastern sector of the advance—a task that meant long hours of staring through scopes, waiting for targets that might never appear, and praying that when they did, you saw them first.

The M36 Jackson’s open-topped turret let in the biting cold. The men huddled in heavy coats, their breath visible in the morning air. To Rose’s left, his loader, Corporal Ben Haskell, checked the ammunition rack. Each shell was nearly three feet long and weighed over forty pounds. The armor-piercing rounds gleamed dull gray in the dim light, the markings still fresh from the factory. Behind them, Sergeant Clay, the commander, scanned the horizon with binoculars, his voice low but steady. “Keep your eyes open. They like to move along that road before noon.”

Rose nodded, but his eyes stayed fixed on the scope. He adjusted the elevation again, just enough to feel the tension in the wheel. Every small movement felt magnified at this range. Even the slightest tremor in his hand could throw off a shot by hundreds of yards. He’d read somewhere that at two miles, a one-degree error in elevation meant missing your target by more than a hundred feet. He wasn’t sure if the statistic was accurate, but it sounded close enough to the truth.

At 11:12, something flickered at the edge of his vision. A dark, angular shape moved slowly across the far horizon. He froze, adjusting the focus of the scope until the image sharpened. The shape resolved into a German Panther tank, its turret glinting faintly in the cold sunlight. It was moving along a distant road, parallel to his position, maybe two and a half miles out. Even through the magnified glass, it looked unreal—like a miniature model sliding across the edge of the world. For a moment, Rose thought his eyes were playing tricks on him. No one engaged armor at that distance. It was too far, too uncertain, too absurd. The manuals said the maximum effective range of the 90mm gun was 2,640 yards. Anything beyond that was simply “theoretical engagement range.” The kind of range that existed in charts and training lectures, not in the mud and chaos of war.

But there it was, the enemy—unaware, exposed, and moving in a straight line. The Panther’s gun barrel pointed forward, not toward him. It wasn’t zigzagging, wasn’t taking evasive action. It was just driving, calm and steady, as if the battlefield were a highway and not a graveyard. Rose’s first instinct was to report the sighting. Let someone else, someone more experienced, take the shot. But the thought died as quickly as it came. He was the only one in position. The other Jacksons were spread out miles apart to avoid artillery fire. This was his responsibility, whether he liked it or not.

He adjusted the focus again, tracing the Panther’s movement across the crosshairs. The range estimation wheel on his scope read 4,600 yards at the far end. He swallowed hard. Two-point-six miles. It might as well have been the moon. The ballistic drop at that range would be monstrous. The shell would arc like a thrown stone, the wind twisting its path, gravity dragging it down long before it reached its mark. But something about the stillness of the moment made him hesitate. The Panther wasn’t moving fast. The air was calm. The slope of the land between them was smooth, open terrain—no obstructions, no trees. For once, the battlefield offered him a clean shot.

He glanced at Haskell. “Range, four-six,” he muttered. Haskell looked up, puzzled. “Four thousand six hundred? You’re kidding.” Rose didn’t answer. He turned back to the scope, his heart pounding in his ears. The reticle lines shimmered slightly from the heat rising off the gun barrel. He steadied his breath, his mind running through everything he knew about the gun’s trajectory, the round’s velocity, the wind direction. None of it felt certain. None of it felt possible.

Yet he kept the crosshairs centered on that small, distant shape moving through the fog.

The Panther’s turret turned slightly, glinting again in the winter light.

And for one long, breathless moment, Lieutenant Alfred Rose—three weeks in command, no confirmed kills—stared through the scope of his M36 Jackson, hands trembling over the elevation wheel, knowing that what he was about to attempt would either make history or end in silence.

Continue below

At 10:42 a.m. on December 1st, 1944, Lieutenant Alfred Rose climbed into the turret of an M36 Jackson tank destroyer positioned on high ground northeast of Beak, Germany, familiarizing himself with controls he barely understood, while German armor prowled the countryside 2 mi away.

26 years old, 3 weeks with the 814th Tank Destroyer Battalion, zero confirmed kills. The Germans had deployed elements of the fifth Panzer Army across the Rhineland, including at least 40 Panther tanks whose frontal armor could deflect American rounds from 800 yardds. Rose’s battalion had lost 11 tank destroyers in November. 17 crewmen dead.

The pattern was always the same. German gunners spotted American positions first, fired first. American crews died before they understood what hit them. The M10 Wolverine tank destroyers they’d been using couldn’t penetrate Panther armor beyond 500 yards.

By the time American crews got close enough for a kill shot, German 88mm guns had already turned their vehicles into burning coffins. The Army’s solution arrived in September. The M36 Jackson 90mm main gun based on the Sherman chassis, but mounting the most powerful American tank gun in Europe. It could penetrate 5.6 6 in of armor at 1500 yd. On paper, it was the answer to the Panther problem.

In reality, Rose had fired exactly four training rounds through the gun. He didn’t know the reticle markings, didn’t know the ranging system, didn’t know if the telescopic sights adjustments matched the technical manual or some field modification nobody had documented. His commander had told him to learn the system fast.

The battalion was being repositioned to support operation clipper. The push to clear German forces from the sigf freed line fortifications around gland kurchchin. Intelligence reported German armor counterattacking along the entire sector. Panthers, tiger tanks, self-propelled guns, the kind of targets that required gunners who knew their equipment cold.

Rose studied the M76F telescopic site mounted in front of the gunner’s position. The reticle showed range markings in 100yd increments. The longest marking read 4,600 yd. Maximum effective range, 2.61 mi. He’d never heard of anyone engaging armor at that distance.

Tank battles happened at 500 yd, maybe a thousand if you had good terrain. Anything beyond that was artillery work. If you want to see how Rose’s crash course in the M36’s systems turned out, please hit that like button. It helps us share more forgotten stories from the Second World War. Subscribe if you haven’t already. Back to Rose. The Jackson’s turret was cramped. Loader to his left. Commander above and behind.

Assistant driver and driver down in the hull. Rose traced his hands over the traverse controls, the elevation wheel, the firing mechanism. Everything felt foreign. 3 weeks wasn’t enough time to develop the muscle memory that kept gunners alive. He needed months. He had hours.

The high ground northeast of Beak offered clear sight lines across the German countryside. Open fields, scattered tree lines, a highway running roughly parallel to their position. Good terrain for spotting targets. Also good terrain for being spotted. German forward observers had been calling in artillery all week.

The battalion had learned to stay dispersed, never clustering more than two vehicles together. Rose pressed his face against the rubber eyepiece of the M76F site. The optics were clean. Magnification was decent. He practiced tracking across the horizon, getting used to how the reticle moved as he adjusted elevation.

The range markings were precise, 400, 800, 1,200, all the way out to that final marking at 4,600 yd. At 11:15, movement caught his eye at the absolute edge of the sight picture. Something dark, angular, moving slowly across his field of view at a distance that seemed impossible for direct fire engagement. The target was moving left to right across Rose’s field of view at what he estimated was extreme range.

Through the M76F telescopic site, the shape resolved into the distinctive silhouette of a German Panther tank. Low profile, long gun barrel, the characteristic sloped armor that made frontal penetration nearly impossible. It was traveling along what appeared to be a road or highway moving at perhaps 6 to 8 mph. Rose’s first instinct was to report the sighting and let someone else deal with it. The range had to be over 2 m.

Nobody engaged tanks at 2 mi. The ballistic drop alone would send rounds sailing over the target or burying into the ground hundreds of yards short. The crosswind would push projectiles off course. The margin for error at that distance was measured in fractions of a degree.

But the Panther wasn’t zigzagging, wasn’t taking evasive action. It was moving in a straight line along that distant road, completely unaware that an American tank destroyer was tracking it from high ground 2 and a half miles away. The kind of target that appeared once in a war if you were lucky, the kind Rose had exactly zero experience engaging. He checked the reticle again.

The M76F site had been designed for the 90 mm gun specifically. The range markings weren’t arbitrary. They’ve been calculated based on the gun’s muzzle velocity, the standard armor-piercing rounds ballistic coefficient, and typical engagement conditions. The engineers who designed this site had included that 4,600 yardd marking for a reason. They believed the gun could reach that far.

Whether it could hit anything at that distance was a different question. Rolls began calculating. The Panther was moving perpendicular to his position. That meant he’d need to lead the target. At 2 and 1/2 miles, the round would take several seconds to reach impact. During that time, the Panther would continue moving. He’d need to aim ahead of the tank by dozens of yards, maybe more.

The exact calculation required knowing the precise range, the exact speed of the target, and the flight time of the projectile. He had none of those numbers with certainty. The M36 Jackson carried two types of main gun ammunition. The M82 armor-piercing capped round was designed for penetrating armor.

It had a large explosive filler that detonated after penetration, maximizing internal damage. At 500 yd, it could punch through 5.1 in of armor. At 1,000 yd, 4.8 in. At 4,600 yd, the penetration tables in the technical manual simply stopped listing values. The assumption was that nobody would attempt shots at that range. Rose understood the physics. Every yard of distance meant more velocity loss, more drop, more wind drift.

By the time an M82 round traveled 4,600 yd, it would have lost significant kinetic energy. It might not penetrate the Panther’s frontal armor even if it hit. But the Panther’s side armor was a different story. 40 to 50 mm thick, 1.6 6 to 2 in. Vulnerable to the 90 mm gun, even at extended range, the target continued its steady movement across the distant highway.

Rose made a decision that violated every principle of tank destroyer doctrine he’d been taught. He was going to attempt the shot, not because he thought it would work, but because this was the only way to learn if the M36’s systems could actually perform at their theoretical maximum range. His hand moved to the traverse control.

He began tracking the panther, keeping it centered in the reticle while his mind raced through the variables he’d need to account for. Rolls called out the sighting to his commander without taking his eye from the telescopic sight. Panther extreme range moving lateral. The commander climbed up beside him, looked through his own optics, and went silent for 5 seconds. When he spoke, his response was simple. Rose’s call. Rose’s shot.

The loader already had an M82 armor-piercing round chambered. Standard procedure. Tank destroyers kept AP rounds loaded at all times when in combat zones. Rose focused on the ranging problem. The M76F site showed distance markings, but estimating range to a moving target at 2 1/2 m required more than eyeballing the reticle.

He needed to bracket the target with ranging shots. Ranging fire was standard practice for artillery. Shoot short, shoot long. Walk the rounds onto target until you found the correct elevation and lead. For a tank destroyer engaging armor at 400 yd, ranging fire was suicide.

It gave away your position, gave the enemy time to return fire or maneuver. But at 4,600 yd, the Panther crew wouldn’t hear the shots, wouldn’t see the muzzle flash, wouldn’t know they were being engaged until rounds started impacting near their position. Rose set the elevation for what he estimated was 4,000 yd, short of where he believed the target actually was.

He wanted to see where the round impacted so he could adjust. The traverse controls allowed him to track the Panthers movement. The tank was maintaining steady speed along that distant highway. Rose led the target by approximately 50 yards, his best guess at compensating for the Panther’s forward movement during the projectile’s flight time.

He pressed the firing trigger. The 90mm gun’s recoil rocked the entire turret. The muzzle blast was tremendous, even with the double baffle muzzle break the army had started installing in November. Smoke and dust obscured the sight picture for 2 seconds.

When it cleared, Rose kept his eye pressed to the optic, watching for impact. At 4,000 y, the time of flight was approximately 6 seconds. Rows counted. 1 2 3 4 5 six. Nothing visible. The distance was too great to see the actual impact through the telescopic site. He’d need to fire again and watch for dust clouds or ground disturbance that might indicate where the round landed.

He adjusted elevation upward, added another 100 yards to his estimate. The Panther was still moving along the highway, apparently unaware that someone was shooting at it from a distance that exceeded normal tank engagement ranges by a factor of four. Rose led the target again, this time by 60 yards to account for increased flight time at the longer range.

Second shot, the gun fired, recoil, smoke. Rose kept the sight trained on the area where he expected impact. 6 seconds of flight time, maybe seven at this range. He counted again while keeping the Panther centered in his field of view. The target continued its steady movement. No indication it was taking evasive action.

No indication its crew had spotted the American position on the high ground northeast of Beck. Then Rose saw it. A small dust cloud erupting on the highway surface approximately 20 yard short of the Panther’s position. The round had impacted close, very close, close enough that Rose now had solid data for his final adjustment. He knew the range. He knew the lead. He knew the ballistic drop. He made one final elevation correction.

Added 10 yards to his lead calculation to account for the Panthers continued forward movement. Set the range marking on the reticle to exactly 4,600 yd. the maximum marking on the M76F telescopic site. He waited for the Panther to move into the precise position where his calculations said the round would intercept the target’s path.

The moment arrived. Rose fired the third shot. The 90mm round covered 4,600 yd in approximately 7 seconds. Rose kept the Panther centered in his telescopic sight, watching for impact. The M82 armor-piercing projectile was traveling at roughly 1,500 ft per second when it left the muzzle.

By the time it reached maximum range, velocity had dropped significantly, but physics favorite rose in one critical way. The Panther’s side armor was only 40 to 50 mm thick. Even a depleted 90mm round retained enough kinetic energy to penetrate that. The hit was visible through the M76F sight as a bright flash on the Panther’s left side hole. Rose had led the target perfectly.

The round struck the tank just behind the front road wheel, precisely where the side armor was thinnest and where the ammunition storage bins were located. The impact was followed immediately by a larger secondary explosion. The Panthers owned 79 rounds of 75mm ammunition detonating inside the fighting compartment. The German tank lurched to a stop. Smoke began pouring from the turret hatches. The crew would be dead or dying.

A direct penetration into the ammunition storage area at that location meant catastrophic internal damage. The blast would have killed the loader instantly. The pressure wave would have incapacitated everyone else in the turret.

Even if some crew members survived the initial explosion, they had seconds to evacuate before the fire reached the fuel tanks. Rose didn’t stop shooting. Standard procedure for tank destroyer crews was to continue engaging until the target was confirmed destroyed. A stopped tank wasn’t necessarily a dead tank. German crews were trained to play dead, waiting for American units to move past before restarting their vehicles and attacking from behind.

Rose had heard stories from other battalions about Panthers that had taken multiple hits, appeared knocked out, then returned to action 30 minutes later after crews made field repairs. He reloaded with another M82 armor-piercing round and fired again. Fourth shot, same point of aim. The round impacted the Panther’s hull near the original penetration point. By now, the internal fire was spreading. The fifth shot used high explosive instead of armorpiercing.

H rounds were devastating against stopped vehicles. The explosion ripped away external components and ensured the fire would consume everything inside the tank. Rose fired a sixth round, then a seventh. He kept shooting until flames were visibly erupting from every hatch and vision port on the Panther.

The thick black smoke characteristic of burning diesel fuel rose from the wreck in a column that would be visible for miles. There was no possibility of that crew surviving. No possibility of that tank returning to service. The engagement had lasted approximately 2 minutes from first shot to confirmed kill. Rose had expended seven 90 mm rounds, three for ranging, four to ensure destruction. The range was 4,600 yd, 2.61 mi.

The maximum effective range of the M76F telescopic site mounted in the M36 Jackson. When Rose finally pulled back from the site, his hands were shaking. Not from fear, from the realization of what he just accomplished. He destroyed a Panther tank at a range that exceeded every engagement distance he’d ever heard of in armored warfare. The shot would go into the 814th Tank Destroyer Battalion’s afteraction report.

It would be witnessed and verified by his commander and the other crew members in the Jackson. It would become part of the official record. What Rose didn’t know was that his confirmed kill at 4,600 yardds would remain the second longest tank versus tank engagement in military history for the next 47 years.

Only 500 yd short of a record that wouldn’t be broken until a British Challenger tank made an impossible shot during the Gulf War in 1991. The burning Panther remained visible on the distant highway for the next 30 minutes. Other American units in the sector reported the smoke column.

Forward observers tried to determine if it was a knocked out German vehicle or a destroyed American position. The 814th Tank Destroyer Battalion’s operations officer eventually confirmed the kill through map coordinates and timeline correlation. Rosa’s position on the high ground northeast of Beak aligned perfectly with the sightelines to the burning wreck. By 1300 hours, word of the shot had spread through the battalion.

A lieutenant nobody had heard of three weeks ago had just made the longest confirmed tank destroyer kill in the European theater. Crews from other M36 Jacksons started asking questions. What range marking did he use? How many ranging shots? What was the lead calculation? Rose didn’t have clean answers. He’d fired by instinct and physics, not by some repeatable formula other gunners could memorize.

The M36 Jackson had only been in combat since September, 4 months of service. American tank destroyer battalions had spent most of 1944 fighting with the M10 Wolverine, a vehicle whose 3-in gun couldn’t reliably penetrate German heavy armor beyond 600 yardds.

The M18 Hellcat was faster, but carried the same underpowered gun. When Panthers and Tigers started appearing in large numbers during the Normandy campaign, American crews found themselves outgunned at every engagement range. The 90mm gun changed that calculation. It was adapted from anti-aircraft artillery, a weapon designed to reach bombers at 15,000 ft altitude.

Mounting that gun in a mobile turret on a Sherman-based chassis gave American forces their first vehicle capable of engaging German heavy armor on equal terms. The M36 could penetrate Panther frontal armor at 1,000 yards. It could destroy Tigers at ranges where the Tiger’s 88 mm gun struggled to penetrate the M36’s frontal slope.

But the weapon’s true capability extended far beyond normal engagement distances. The 90mm M3 gun had a muzzle velocity of 2,700 ft pers. The M82 armor-piercing round weighed 24 lb. Basic physics said that combination could reach targets at 4,000 yd or more. The question wasn’t whether the gun could shoot that far. The question was whether anyone could aim accurately enough to hit a moving tank at that distance.

Rose had answered that question. Not through superior training, not through months of practice, through two ranging shots that gave him the data he needed to make the third shot count. The engagement demonstrated something the Army’s ordinance department had suspected, but never confirmed in combat. The M76F telescopic sight’s maximum range marking of 4,600 yd wasn’t theoretical.

It was functional. German forces in the sector continued operating Panthers throughout December. Rose’s battalion encountered them regularly during the push toward the Roar River, but none of those engagements happened at extreme range. German crews had learned from two years of fighting on the Eastern Front. They used terrain. They avoided open ground.

They positioned their tanks in covered positions where American forces would have to close to within 500 yd to get clear shots. The conditions that allowed Rose’s shot were unique. High ground providing elevation advantage, open terrain with clear sight lines, a German crew moving along an exposed highway without taking tactical precautions, and a gunner who was willing to attempt something that doctrine said was impossible.

Those conditions wouldn’t repeat themselves for the rest of the war. By mid December, the German counteroffensive in the Arden pulled most American armored units away from the roar sector. The 814th Tank Destroyer Battalion redeployed to support operations against the Bulge. Rose would fire his M36’s 90mm gun many more times before Germany surrendered in May, but he would never again attempt a shot at 4,600 yd.

The Battle of the Bulge began 16 days after Rose’s record shot. On December 16th, German forces launched their massive counteroffensive through the Arden Forest. Three entire armies, 200,000 troops, 600 tanks, including the newest Panthers and King Tigers. The offensive caught American forces completely offguard.

Within 48 hours, German armored spearheads had penetrated 30 m into Allied lines. The 8/14th tank destroyer battalion received emergency orders on December 18th. Redeploy south immediately. Support the 7th Armored Division at Sankv Ve. The town was a critical road junction. If German forces captured it, they would have direct access to the Muse River crossings.

The entire northern shoulder of the American defensive line would collapse. Rose’s company moved through Belgium in darkness. The roads were chaos. Supply trucks heading west away from the German advance. Infantry units trying to reach defensive positions. Artillery batteries repositioning under fire.

The 814th arrived at Saintv on December 19th and immediately went into action. German Panther battalions were already engaging American positions on the eastern approaches to the town. The fighting around Sanct bore no resemblance to Rose’s long range engagement at Beak. This was close quarters armor combat. Panthers appearing from tree lines at 300 yards.

American tank destroyers firing from behind burning buildings. German infantry with panzer fousts hunting M36s through village streets. The kind of fighting where the side that spotted first won where hesitation measured in seconds meant death. Roses Jackson took up position on the southern edge of San Vith on December 20th.

His field of fire covered a road junction where German armor was expected to attack. The range was 800 yd. Standard engagement distance. No exotic calculations required. Just point the 90mm gun at center mass and shoot when targets appeared. The attack came at dawn on December 21st. Four Panthers supported by two companies of Panzer grenaders.

Rose’s company knocked out two Panthers in the first minute of fighting. German return fire destroyed one M36 and damaged two others. The engagement lasted 14 minutes. When it ended, all four German tanks were burning and the infantry had withdrawn. American casualties were three tank destroyers destroyed, 11 crew members dead or wounded. Rose survived Sank Viff.

His Jackson took two hits from German 75mm guns, both deflected by the frontal armor. The M36’s sloped glasses plate was effectively 140 mm thick when hit at angle. German guns struggled to penetrate it beyond 600 yd, but the open topped turret was vulnerable to artillery air bursts and plunging fire. Several M36s in the battalion were knocked out by indirect fire during the week-long defense of Saintv.

By December 23rd, American forces had to abandon the town. German pressure was overwhelming. The seventh armored division conducted a fighting withdrawal westward. The 8/14th tank destroyer battalion provided rear guard, engaging German pursuit forces at every defensible position. Rose fired his 90mm gun 43 times during the withdrawal.

All at ranges under 1,000 yards, all at targets he could see clearly through his telescopic sight. The contrast with his December 1st engagement was absolute. At Beak, he’d had time to calculate, time to range his shots, time to methodically engage a target that didn’t know it was being hunted. At Sanctit and during the withdrawal, combat happened at reflex speed.

See target, identify target, fire. No ranging shots, no careful calculations, just the desperate mathematics of kill or be killed armor warfare. Rose would never forget the panther burning on that distant highway at 4,600 yd. But the shots that kept him alive through the bulge were the ones he made at point blank range against tanks that were shooting back.

The 814th Tank Destroyer Battalion spent January 1945 reconstituting after the bulge. The battalion had lost 19 M36 Jacksons during the German offensive. 26 crew members killed, 41 wounded. Replacement vehicles arrived from depot stocks in France. Replacement crews came straight from training facilities in the United States.

Most had never fired a 90mm gun in combat. Rose found himself training the new gunners, teaching them the M76F telescopic site, explaining how to estimate range, how to lead moving targets, how to adjust for wind and elevation. The new crews asked about his 4,600yd shot. Rose told them to forget it. That kind of engagement happened once in a war.

What they needed to learn was how to kill panthers at 500 yardds while under fire. That was the skill that kept tank destroyer crews alive. By February, the battalion was back in action. American forces were pushing toward the Ryan River. German resistance was collapsing, but remained fierce at key defensive positions.

Panthers and King Tigers still appeared wherever the Vermacht tried to hold ground. The M36 Jackson remained the most effective American answer to German heavy armor. Its 90mm gun could penetrate any German tank from the front at normal combat ranges. Rose participated in the Ryan crossing operations in March. His Jackson was part of the support element for the 9inth Army’s assault near Vasil.

German forces on the east bank included elements of three Panzer divisions. The fighting was intense but brief. American air superiority and overwhelming artillery support broke German defensive positions within 48 hours. Rose’s company knocked out six Panthers and two King Tigers during the crossing, all at ranges under 800 yardds.

April brought the final push into Germany’s industrial heartland. The 814th Tank Destroyer Battalion advanced through the rurer pocket, engaging scattered German resistance. Most German armor units had been destroyed or had run out of fuel. The panthers and tigers that had dominated European battlefields for 2 years were burning wrecks or abandoned hulls scattered across hundreds of miles of terrain.

Rose saw his last combat action on April 23rd near the Elb River. A single panther appeared from a farm complex at approximately 600 yardds. The German crew was attempting to retreat eastward ahead of American forces. Rose engaged with two rounds. Both hits. the Panther burned. It was his 47th confirmed kill with the M36’s 90mm gun.

46 of those kills happened at ranges under 1,000 yards. Germany surrendered on May 8th. The 814th Tank Destroyer Battalion received orders to prepare for redeployment to the Pacific theater. The plan was to equip the battalion with newer M36 variants and use them against Japanese armor in the expected invasion of the home islands.

The atomic bombs dropped in August made that invasion unnecessary. Rose never fired the 90mm gun in combat again. The afteraction reports from December 1st, 1944 remained in the battalion’s official records. Lieutenant Alfred Rose, M36 Jackson, Panther destroyed at 4,600 yards, witnessed and verified. The shot was documented in multiple Army publications over the following decades.

Military historians analyzing tank warfare cited it as evidence of the M36’s capabilities. Gunnery instructors used it as an example of what was theoretically possible with proper ranging and calculation. But the shot’s real significance wasn’t the distance. It was what the engagement revealed about the evolution of armored warfare.

The M36 Jackson represented the culmination of American tank destroyer development during the Second World War. A vehicle that could engage and destroy the most heavily armored German tanks at ranges that exceeded anything Doctrine had anticipated. Rose’s shot at 4,600 yd proved the weapon could perform at the absolute limits of its design specifications.

And for 47 years, that record stood as the second longest tank kill in military history. The record rose set on December 1st, 1944 remained unbroken through Korea, through Vietnam, through decades of Cold War tank development and doctrine refinement. The United States Army continued improving its armored vehicle capabilities.

Better guns, better fire control systems, better ammunition, but no American tank crew ever documented a confirmed kill at a greater range than Rose’s 4,600 yd. The British Army broke the record on February 26th, 1991. A Challenger 1 main battle tank with the call sign 11B was operating in Iraq during Operation Desert Storm. The crew spotted an Iraqi tank at extreme range during the ground war to liberate Kuwait.

The gunner fired a depleted uranium round using advanced fire control computers and thermal imaging systems that didn’t exist in 1944. The round impacted at 5,100 yd, 3.1 mi. the longest confirmed tank versus tank kill in military history. Rose’s shot fell to second place, but context matters. The Challenger crew in 1991 had laser rangefinders, ballistic computers, stabilized gun platforms, digital fire control systems that automatically calculated lead and elevation.

Rose had mechanical controls, an optical sight, and three years of wartime experience compressed into three weeks. He made his shot with tools from 1944 against a target moving at maximum engagement range in combat conditions. The M36 Jackson remained in American service through the Korean War.

The vehicle performed well against North Korean and Chinese armor. Its 90mm gun could penetrate any tank the communist forces deployed, but engagement ranges in Korea were typically much shorter than in Europe. Mountain terrain and limited sight lines meant most tank battles happened at ranges under 500 yd. No gunner replicated Rose’s extreme range engagement. Rose survived the war.

He left active duty in 1946 and returned to civilian life. The Army tried to recruit him for gunnery instructor positions at Fort Knox, but he declined. He’d spent three years shooting at people. He was done. The records show he never spoke publicly about his December 1st engagement. No interviews, no memoirs, no attempts to capitalize on being part of military history.

The afteraction reports remained in the archives. Historians discovered them decades later while researching tank destroyer operations in Northwest Europe. The engagement at 4,600 yardds appeared in several academic papers on armored warfare. Military analysts used it as a case study in the limits of direct fire engagement.

The shot represented the absolute maximum effective range for Second World War era tank guns operating under ideal conditions. If this story moved you the way it moved us, do me a favor, hit that like button. Every single like tells YouTube to show this story to more people. Hit subscribe and turn on notifications.

We’re rescuing forgotten stories from dusty archives every single day. Stories about tank destroyer gunners who saved lives with calculations and cold precision. Real people, real heroism. Drop a comment right now and tell us where you’re watching from. Are you watching from the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, Australia? Our community stretches across the entire world. You’re not just a viewer. You’re part of keeping these memories alive. Tell us your location.

Tell us if someone in your family served. Just let us know you’re here. Thank you for watching and thank you for making sure Lieutenant Alfred Rose doesn’t disappear into silence. These men deserve to be remembered, and you’re helping make that

News

CH2 The Secret Weapon the U.S. Navy Hid on PT Boats — And Japan Never Saw It Coming

The Secret Weapon the U.S. Navy Hid on PT Boats — And Japan Never Saw It Coming October 15th, 1943….

CH2 Japanese Soldiers Were Terrified When U.S. Marines Used Quad-50s to Destroy Their Banzai Charges

Japanese Soldiers Were Terrified When U.S. Marines Used Quad-50s to Destroy Their Banzai Charges The morning of February 8th,…

CH2 What Japanese Admirals Said When American Carriers Crushed Them at Midway

What Japanese Admirals Said When American Carriers Crushed Them at Midway At 10:25 a.m. on June 4th, 1942, Admiral…

CH2 How a U.S. Sniper’s ‘Car Battery Trick’ Killed 150 Japanese in 7 Days and Saved His Brothers in Arms

How a U.S. Sniper’s ‘Car Battery Trick’ Killed 150 Japanese in 7 Days and Saved His Brothers in Arms …

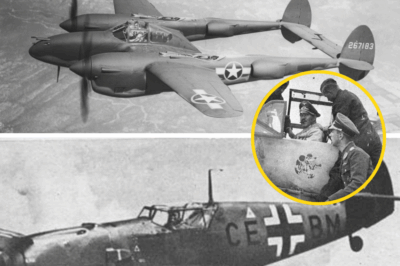

CH2 German Pilots Were Shocked When P-38 Lightning’s Twin Engines Outran Their Bf 109s

German Pilots Were Shocked When P-38 Lightning’s Twin Engines Outran Their Bf 109s The sky over Tunisia was pale…

CH2 When The Germans Saw The American Jeep Roaming On D-Day – Their Reaction Showed How Doomed Germany Was…

When The Germans Saw The American Jeep Roaming On D-Day – Their Reaction Showed How Doomed Germany Was… June 7th,…

End of content

No more pages to load