They Mocked This “Suicidal” Fighter — Until One Pilot Stopped 30 German Attackers Alone

February 14th, 1943. The Cassarine Pass, Tunisia. Dawn breaks cold over the desert. The air tastes like iron and sand. An American M4 Sherman sits hauled down behind a rgeline. Its 75mm gun, traversing left, then right, searching for movement. Inside, five men breathe in short bursts.

The driver’s hands grip the levers. The gunner’s eye presses against the sight. They have been in combat for three days. Then they see it. A Panzer 4 emerges from the Wadi below. Its long barrels sweeping the horizon. Behind it, two more. The German tanks move with practiced confidence. Turrets rotating in coordinated arcs.

They have done this before in Poland, in France, in Russia. They know what American armor looks like. They have heard the reports. thin armor, undertrained crews, machines built by a nation that does not understand war. The Sherman commander whispers into the intercom. Gunner, target tank. The German crews do not rush. They have time.

They have always had time. They are wrong. The Sherman fires first. The desert erupts in flame and thunder. The lead panzer four shutters. smoke pouring from its engine deck. The other two German tanks halt, turrets snapping toward the ridge. For a moment, confusion, then anger. This is not how it was supposed to go.

To understand how the Sherman became the tank that broke the Wehrmacht, you must first understand what came before it. In 1940, the United States Army had fewer than 400 tanks. Most were obsolete. The M2 light tank carried machine guns and hope. The M2 medium tank existed only in prototype form, a relic before it ever saw combat.

While German panzers carved through France and British Matildas struggled in North Africa, America possessed no modern armored force, no doctrine, no experience, no time. The fall of France changed everything. In June 1940, as the swastika rose over Paris, American military planners watched their assumptions collapse. Tank warfare was no longer theoretical.

It was the future. And America was years behind. The first response was desperation. Engineers at the Rock Island Arsenal worked 18-hour shifts. The M3 Grant, called the Lee by Americans, emerged in early 1941. It was a compromise wrapped in riveted steel.

The main gun, a 75mimeter cannon, sat in a sponsson on the right side of the hull. This meant the entire tank had to turn to aim. The design was outdated before the first one rolled off the assembly line, but it was what America had. The M3 went to the British first, shipped across the Atlantic under lend lease. British crews took them into the western desert in 1942 at Gazala.

At first Alamine, the Grants fought Raml’s Africa core. They were tall, awkward. The rivets inside became shrapnel when struck. Crews called them flaming coffins. But the 75mm gun could hurt German armor, and that was something. Still, everyone knew the M3 was a stop gap. Even as production ramped up, American engineers were already designing its replacement.

The requirements were clear. A medium tank with a 75 mm gun in a fully rotating turret, reliable mechanics, and the ability to be mass-produced faster than any tank in history. Speed mattered more than perfection. Industrial capacity mattered more than individual superiority.

In September 1941, the first prototype of the medium tank M4 was completed. It had a cast hull, a right radial aircraft engine, and a low profile compared to the M3. The 75mm gun sat in a proper turret. The suspension used a vertical Volute spring system, simple, reliable, easy to repair.

The armor was 51 mm at the front, sloped at 56° on the hall, not thick by German standards, but angled enough to matter. By February 1942, the M4 was in full production. Factories in Detroit, in Grand Blanc, in Fiser body plants across the Midwest began turning out Shermans at a staggering pace. welded hauls, cast hauls, different engines, Ford GIAV8s, Chrysler multibank engines, GM diesels.

The design was modular, adaptable, built for a nation that could outproduce the world. The name Sherman came from the British who named American tanks after Civil War generals. It stuck. By mid 1942, the first Shermans were crossing the Atlantic, bound for North Africa, where British and American forces prepared for Operation Torch.

The tank was untested, the crews were green, and across the Mediterranean, German tankers sharpened their skills against Soviet T34s, preparing for the amateurs about to enter the war. The Germans had earned their confidence. Since 1939, the Panzer divisions had rewritten the rules of warfare. In Poland, they shattered defenses in 18 days.

In France, they bypassed the Majino line and reached the English Channel in 10. In Russia, they encircled entire Soviet armies, capturing hundreds of thousands in single operations. By 1942, German tankers were veterans of a hundred battles. They knew their machines.

They trusted their tactics, and they had faced the best the Soviets and British could field. When intelligence reports described the new American tank, the M4 Sherman, the response was dismissive, adequate at best. The armor was thin. The gun was only 75 little shorter barrel than the German versions. The silhouette was tall, an easy target compared to the Panzer 4 with its long 75 mm KWK40 or the Tiger Rand with its 88 mm gun and 100 mil of frontal armor. The Sherman seemed like a child’s toy sent to a professional’s war.

German tank commanders shared their assessments over schnaps and cigarettes. The Americans were wealthy but soft. Their equipment built for quantity over quality. The Sherman would burn like the M3 before it. It would break down in the desert. Its crews would panic under fire. This was the consensus. This was the comfortable arrogance of men who had conquered a continent and believed themselves invincible.

But arrogance is a luxury built on dwindling resources. And by 1943, the Wehrmacht was beginning to feel the strain. On the Eastern Front, the tide had turned. Stalinrad had fallen. In February 1943, the same month American Shermans entered combat in Tunisia. The Sixth Army was annihilated. 300,000 men lost. The Soviets were counterattacking with a ferocity that shocked German commanders. T-34s came in waves.

They were crude but effective. And there were always more.

Continue below

February 14th, 1943. The Cassarine Pass, Tunisia. Dawn breaks cold over the desert. The air tastes like iron and sand. An American M4 Sherman sits hauled down behind a rgeline. Its 75mm gun, traversing left, then right, searching for movement. Inside, five men breathe in short bursts.

The driver’s hands grip the levers. The gunner’s eye presses against the sight. They have been in combat for three days. Then they see it. A Panzer 4 emerges from the Wadi below. Its long barrels sweeping the horizon. Behind it, two more. The German tanks move with practiced confidence. Turrets rotating in coordinated arcs.

They have done this before in Poland, in France, in Russia. They know what American armor looks like. They have heard the reports. thin armor, undertrained crews, machines built by a nation that does not understand war. The Sherman commander whispers into the intercom. Gunner, target tank. The German crews do not rush. They have time.

They have always had time. They are wrong. The Sherman fires first. The desert erupts in flame and thunder. The lead panzer four shutters. smoke pouring from its engine deck. The other two German tanks halt, turrets snapping toward the ridge. For a moment, confusion, then anger. This is not how it was supposed to go.

To understand how the Sherman became the tank that broke the Wehrmacht, you must first understand what came before it. In 1940, the United States Army had fewer than 400 tanks. Most were obsolete. The M2 light tank carried machine guns and hope. The M2 medium tank existed only in prototype form, a relic before it ever saw combat.

While German panzers carved through France and British Matildas struggled in North Africa, America possessed no modern armored force, no doctrine, no experience, no time. The fall of France changed everything. In June 1940, as the swastika rose over Paris, American military planners watched their assumptions collapse. Tank warfare was no longer theoretical.

It was the future. And America was years behind. The first response was desperation. Engineers at the Rock Island Arsenal worked 18-hour shifts. The M3 Grant, called the Lee by Americans, emerged in early 1941. It was a compromise wrapped in riveted steel.

The main gun, a 75mimeter cannon, sat in a sponsson on the right side of the hull. This meant the entire tank had to turn to aim. The design was outdated before the first one rolled off the assembly line, but it was what America had. The M3 went to the British first, shipped across the Atlantic under lend lease. British crews took them into the western desert in 1942 at Gazala.

At first Alamine, the Grants fought Raml’s Africa core. They were tall, awkward. The rivets inside became shrapnel when struck. Crews called them flaming coffins. But the 75mm gun could hurt German armor, and that was something. Still, everyone knew the M3 was a stop gap. Even as production ramped up, American engineers were already designing its replacement.

The requirements were clear. A medium tank with a 75 mm gun in a fully rotating turret, reliable mechanics, and the ability to be mass-produced faster than any tank in history. Speed mattered more than perfection. Industrial capacity mattered more than individual superiority.

In September 1941, the first prototype of the medium tank M4 was completed. It had a cast hull, a right radial aircraft engine, and a low profile compared to the M3. The 75mm gun sat in a proper turret. The suspension used a vertical Volute spring system, simple, reliable, easy to repair.

The armor was 51 mm at the front, sloped at 56° on the hall, not thick by German standards, but angled enough to matter. By February 1942, the M4 was in full production. Factories in Detroit, in Grand Blanc, in Fiser body plants across the Midwest began turning out Shermans at a staggering pace. welded hauls, cast hauls, different engines, Ford GIAV8s, Chrysler multibank engines, GM diesels.

The design was modular, adaptable, built for a nation that could outproduce the world. The name Sherman came from the British who named American tanks after Civil War generals. It stuck. By mid 1942, the first Shermans were crossing the Atlantic, bound for North Africa, where British and American forces prepared for Operation Torch.

The tank was untested, the crews were green, and across the Mediterranean, German tankers sharpened their skills against Soviet T34s, preparing for the amateurs about to enter the war. The Germans had earned their confidence. Since 1939, the Panzer divisions had rewritten the rules of warfare. In Poland, they shattered defenses in 18 days.

In France, they bypassed the Majino line and reached the English Channel in 10. In Russia, they encircled entire Soviet armies, capturing hundreds of thousands in single operations. By 1942, German tankers were veterans of a hundred battles. They knew their machines.

They trusted their tactics, and they had faced the best the Soviets and British could field. When intelligence reports described the new American tank, the M4 Sherman, the response was dismissive, adequate at best. The armor was thin. The gun was only 75 little shorter barrel than the German versions. The silhouette was tall, an easy target compared to the Panzer 4 with its long 75 mm KWK40 or the Tiger Rand with its 88 mm gun and 100 mil of frontal armor. The Sherman seemed like a child’s toy sent to a professional’s war.

German tank commanders shared their assessments over schnaps and cigarettes. The Americans were wealthy but soft. Their equipment built for quantity over quality. The Sherman would burn like the M3 before it. It would break down in the desert. Its crews would panic under fire. This was the consensus. This was the comfortable arrogance of men who had conquered a continent and believed themselves invincible.

But arrogance is a luxury built on dwindling resources. And by 1943, the Wehrmacht was beginning to feel the strain. On the Eastern Front, the tide had turned. Stalenrad had fallen. In February 1943, the same month American Shermans entered combat in Tunisia. The Sixth Army was annihilated. 300,000 men lost. The Soviets were counterattacking with a ferocity that shocked German commanders. T-34s came in waves.

They were crude but effective. And there were always more. Panzer divisions that had seemed unstoppable in 1941 were now bleeding out in the mud and snow of Russia. Their losses irreplaceable. In the West, Germany faced a different challenge. British and American bombers struck industrial centers with increasing regularity.

Factories that produced tank components, synthetic fuel plants, rail yards, all were under assault. The logistical network that fed the Panzer divisions was fraying. Spare parts became precious. Fuel shipments uncertain. Every tank lost in combat was harder to replace. Yet the German tank crews themselves remained formidable. Their training was rigorous, their doctrine refined through years of combat.

They understood combined arms warfare using infantry, artillery, and air support in coordination with armor. They knew how to use terrain, how to ambush, how to withdraw and regroup. A veteran Panzer commander with a well-maintained Panzer 4 could still dominate a battlefield, destroying multiple enemy tanks before being forced to retreat.

This was the expertise the Americans would face. But expertise, no matter how refined, cannot hold a line when outnumbered 10 to one. The strategic situation in early 1943 was precarious for Germany. North Africa was the last axis foothold on the southern front. Ruml’s Africa corps, reinforced by Italian units, held a defensive line in Tunisia.

Supply lines stretched across the Mediterranean, vulnerable to Allied air and naval power. Every ship sunk meant fewer tanks, less ammunition, no replacement parts. The German forces in Tunisia were being slowly strangled. Into this theater came the Americans, untested and underestimated. The first major engagement was at Casarine Pass in midFebruary.

German forces led by Raml himself launched an offensive to disrupt the American buildup. The US2 core equipped with a mix of M3 Lees and M4 Shermans was caught offguard. Coordination broke down. Units retreated in confusion. The Germans advanced 20 m in two days. It looked like validation. The Americans were as weak as expected. Their tanks burned, their infantry scattered.

Raml reported the enemy was poorly trained and tactically naive. The Casarine Pass became a lesson, but not the one the Germans thought. Because while the Americans lost tanks and men, they learned rapidly, ferociously. The two corps was reorganized under new command. Training intensified. Coordination between infantry, armor, and artillery improved.

The Sherman crews who survived Casserine understood now what they faced. They studied German tactics. They practiced maneuvers until the movements became instinct. And behind them across the ocean, factories produced more Shermans. Hundreds more. Thousands more. By March 1943, the Americans counterattacked. At Elguitar, Shermans and tank destroyers held off German armor in a grinding defensive battle.

The 75W gun, dismissed as inadequate, proved capable of penetrating Panzer 4 armor at combat ranges. The Sherman’s mobility allowed rapid repositioning. Its reliability meant it could fight day after day without breaking down. Slowly, the balance shifted. The German mockery began to fade.

Officers who had laughed at intelligence reports now filed new assessments. The Sherman was not superior in armor or firepower, but it was competent. And competence, when multiplied by overwhelming numbers, was lethal. In May 1943, the Axis forces in Tunisia surrendered. Over 250,000 German and Italian troops were captured.

The Africa Corps, Raml’s legendary formation, ceased to exist. Among the wreckage were burned out panzers, their crews dead or captured, destroyed by tanks they had once mocked. The Shermans had proven they could fight. Now they would prove they could conquer. The lessons from North Africa reverberated across the Allied command.

The Sherman was not perfect, but it was good enough. More importantly, it was everywhere. British forces received thousands under lend lease. Soviet forces, despite their preference for homegrown designs, accepted shipments. The free French, the Poles, the Canadians, all fielded Shermans.

It became the common standard, the universal tool of Allied armored warfare. And the production numbers were staggering. In 1942, American factories produced 3,400 Shermans. In 1943, that number rose to 14,000. By 1944, it exceeded 16,000. Germany, by comparison, produced roughly 6,000 panzer fees and one to 300 Tigers in 1943.

The Americans were not building better tanks. They were building an unstoppable tide. The Vermach faced a new reality. Every Sherman destroyed was replaced by three more. Every experienced panzer crew lost could not be replaced at all. The calculus of armored warfare, once in Germany’s favor, was inverting.

And the Germans, for all their skill and courage, could not stop what was coming. Inside a Sherman, the world became small and hot and loud. Five men shared a space barely larger than a closet. The driver sat low in the hull, hands on twin levers, eyes fixed on a narrow periscope.

Beside him, the assistant driver manned the bow machine gun, his view of the battlefield reduced to a slit. Above in the turret, the commander stood in the cupula, half exposed, scanning for threats. The gunner crouched over his sights. The loader hefted 75 mm of shells, each weighing 40 lbs, slamming them into the brereech as fast as his muscles allowed. These men were not professional soldiers.

They were farm boys from Iowa, factory workers from Pennsylvania, clerks from California. They had trained for months, learning to drive the 30-tonon machine over obstacles to fire the gun at moving targets to coordinate their actions until they functioned as one organism. But training is not combat.

And in 1943, American tankers learned the difference quickly. The Germans had years of experience. Their crews communicated in shortorthhand, anticipated each other’s movements, knew instinctively when to advance and when to retreat. They had developed tactics that exploited the Sherman’s weaknesses, targeting the tall hull, aiming for ammunition stowage, using superior optics to engage at longer ranges.

A veteran German gunner could kill a Sherman before the American crew even spotted the threat. But the Americans learned. After every battle, after every loss, the survivors talked. They shared what worked, what didn’t, how to use terrain to mask the Sherman’s height, how to advance in groups, suppressing enemy positions with concentrated fire, how to recognize the flash of a German gun, and return fire within seconds.

The learning curve was steep and written in blood, but it was real. By mid 1943, American tank crews were no longer noviceses. They understood their machine strengths, speed, reliability, gun stabilization that allowed firing on the move. They accepted its weaknesses and adapted tactics accordingly.

They learned to fight smart, using numerical superiority to overwhelm German positions. Three Shermans could encircle a Panzer 4, hitting it from multiple angles, ensuring at least one shot penetrated. It was methodical, brutal, effective, and they kept coming. That was the psychological edge. A German crew might destroy two Shermans, three, even five. But there were always more.

Always another wave cresting the hill, tracks churning, guns blazing. The Americans could afford losses. The Germans could not. And every engagement eroded German confidence a little more. On paper, the Sherman was outmatched. The armor was 51 mil peritter on the front glasses, 76 cilanted on the turret front, adequate against most German guns at range, vulnerable up close.

The 75 and M3 gun could penetrate roughly 90 mm of armor at 500 yd, sufficient against Panzer 3s and early Panzer 4s, but struggling against the later models with upgraded armor and the Tiger’s 100 mm to frontal plate. The German response was to build heavier, more powerful tanks.

The Panzer 4, upgraded with a longbarreled 75mm gun, could penetrate Sherman armor at over 1,000 yards. The Tiger Wears, introduced in late 1942, was a fortress on tracks, 56 tons, 100 millm of frontal armor, and 88 mm gun that could destroy any Allied tank at ranges exceeding 1,500 yardds.

The Panther, arriving in mid 1943, combined sloped armor with a high velocity 75mm gun, making it nearly invincible from the front. But tactical superiority is not the same as battlefield effectiveness. The Sherman had advantages that statistics did not capture. Its 75mm gun was mounted in a gyro stabilizer, allowing reasonably accurate fire while moving.

a capability German tanks lacked. This meant a Sherman could shoot first while advancing, forcing German crews to halt, aim, and fire from a stationary position. In fluid engagements, speed and first shot capability, mattered more than armor thickness. The Sherman’s engine, usually a Continental R975 radial or a Ford GAA V8, was reliable.

It started in cold weather, ran for hundreds of miles without major maintenance, and used widely available fuel. German tanks, by contrast, were mechanical marvels prone to breakdown. The Tiger’s Maybach engine was powerful but temperamental. The Panther’s transmission was notorious for failure, especially in early models. A tank that cannot move is not a weapon.

It is a tomb. The Sherman’s design prioritized ease of repair. Its modular construction meant damaged components could be swapped in the field. The vertical vollet spring suspension was simple and robust, far less prone to failure than the complex torsion bars used in German designs. American maintenance crews could return a damaged Sherman to combat within hours. German crews often waited days for spare parts that never arrived.

And then there was the human factor inside the machine. The Sherman’s interior was relatively spacious with good visibility for the commander and an escape hatch for every crew member. German tanks, especially the Tiger and Panther, were cramped and difficult to evacuate under fire.

American tankers had a better chance of surviving a hit and living to fight another day. Experienced crews were irreplaceable, and the Sherman’s design helped keep them alive. The Sherman was not designed to be the best tank. It was designed to be the tank America could produce in overwhelming numbers without crippling its economy.

This distinction defined the entire Allied approach to armored warfare. In 1942, the United States produced more tanks than Germany, Britain, and the Soviet Union combined. By 1943, American factories were completing a Sherman every hour. 11 plants across the country manufactured components. Fisher body in Grand Blank, Michigan alone produced 11,000 Shermans during the war.

The tanks rolled off assembly lines faster than crews could be trained to man them. This was the application of American industrial philosophy, standardization, mass production, interchangeable parts. Henry Ford’s innovations refined over decades applied to military hardware. A Sherman built in Detroit was identical to one built in California.

A crew trained on one could operate any other without retraining. Spare parts from one batch fit tanks from another. The entire system was designed for volume and efficiency. Germany, by contrast, built tanks like artisans. Each panther, each tiger was a complex piece of engineering assembled by skilled workers using precision tools. Quality was high, but production was slow.

A Tiger took twice as long to build as a Sherman and required specialized parts that could not be easily sourced. When the crop factories were bombed, Tiger production suffered. When rail lines were cut, completed tanks sat idle, unable to reach the front. The strategic implication was profound. America could lose five Shermans for every Panther destroyed and still maintain numerical superiority.

Germany could not trade losses at any ratio. Every tank lost was a permanent reduction in combat power. The Vermach’s Panzer divisions, once the terror of Europe, were being ground down by attrition, not because the Shermans were better, but because there were simply too many to stop.

And the Americans kept refining the design. The M4 A1 with the cast hull, the M4 A2 with the diesel engine for the Soviets, the M4 A3 with the Ford V8, which became the standard US variant. Later, the 76mm gun would be introduced, improving anti-armour capability.

The jumbo Sherman with extra armor for assault roles, flamethrower versions, recovery vehicles. Each iteration addressed battlefield lessons without halting production. This was the genius of the Sherman. It was not a super weapon. It was a system, a continuously improving platform backed by the largest industrial base in human history. The Germans mocked it because they did not understand that wars are not won by the best tank.

They are won by the side that can field enough tanks, keep them running, and replace them when they are destroyed. And in that contest, there was never any doubt who would win. In the officer’s mess of a panzer regiment stationed in Normandy spring 1944, a young lieutenant voiced what many thought but few said aloud, “They just keep coming.

” He was describing his encounter with American armor during training exercises simulating Allied tactics. His commander, a veteran of Russia and North Africa, dismissed the concern. American tanks are targets, not threats. Remember that. But the whispers were spreading.

Letters from the Eastern Front spoke of endless Soviet tank columns, T34s advancing despite horrific losses. Now, in the West, a similar pattern was emerging. The Shermans were not individually superior, but they attacked in groups of 10, 20, sometimes 50 at once. They coordinated with infantry and artillery. They used smoke and suppressing fire. They did not fight like gentlemen. They fought like industrialists waging a war of material.

German tankers prided themselves on offre’s tactic, mission type tactics that emphasized initiative and flexibility. A panzer commander was expected to assess the battlefield and make decisions independently. This worked brilliantly when German forces held numerical and qualitative superiority.

But by 1944, those advantages were evaporating. A single Tiger could dominate a battlefield until it ran out of ammunition or fuel or broke a track and could not be repaired because the supply convoy was destroyed by Allied air power. The German military machine, so efficient in 1940, was crumbling under the weight of a multiffront war. Training time for new tank crews was cut from months to weeks.

Replacement tanks arrived with defects because factories were rushing production and operating under constant air attack. Fuel shortages meant combat vehicles sat idle while infantry marched. The Panzer divisions that invaded France in 1940 with hundreds of tanks now fielded dozens. Their ranks filled with repurposed assault guns and captured vehicles.

And yet individual German tank crews remained extraordinarily dangerous. A skilled commander in a Panther or Tiger could still destroy multiple Shermans in a single engagement. At Valer Bukage in June 1944, a single Tiger commanded by SS Overber Sturmfurer Michael Vitman destroyed an entire British armored column, 14 tanks, 15 personnel carriers, and two anti-tank guns in less than 15 minutes.

Such feats reinforced the belief that German armor was superior, that quality mattered more than quantity. But Vitman’s Tiger was eventually destroyed. And when it was, there was no replacement. The crew among Germany’s most experienced was gone forever. Meanwhile, the British and American tanks they destroyed were replaced within days.

The strategic mathematics was inescapable. Germany was losing a war of attrition it could not afford to fight. German intelligence reports from mid 1944 onward reflected a shift in tone. The Sherman was no longer described as inferior, but as adequate in mass employment. Tactical bulletins advised Panzer crews to avoid prolonged engagements with numerically superior forces, to strike and withdraw, to conserve strength.

These were the tactics of a defensive war, not a conquering army. The mockery had ceased. In its place was a grim acknowledgment. The Americans had more tanks than Germany could ever destroy. The philosophical debate over tank warfare in World War II can be distilled into two opposing doctrines.

The Germans believed in the decisive power of superior technology wielded by elite units. The Americans believed in the overwhelming application of adequate technology across a broad front. German Panzer doctrine emphasized the tank as a breakthrough weapon. Concentrated armor would punch through enemy lines, encircle defenders, and collapse entire fronts. This required tanks that could dominate individual engagements.

Thick armor, powerful guns, superior optics. The Tiger and Panther embodied this philosophy. They were designed to win one-on-one duels, to strike fear, to be worth 10 enemy tanks each. The American approach was fundamentally different. The Sherman was designed to support infantry, exploit breakthroughs, and sustain prolonged operations. It was not meant to hunt enemy tanks.

That was the job of tank destroyers like the M10 and M18. The Sherman’s role was to keep moving, to maintain pressure, to ensure the front never stabilized. Speed and reliability mattered more than individual combat power. This doctrinal difference shaped every aspect of tank employment. German Panzer divisions, when fully equipped, were devastating but brittle.

lose a handful of Tigers and the division’s offensive capability collapsed. American armored divisions, even after heavy losses, could reconstitute and attack again within days because replacement Shermans and crews were constantly arriving. The terrain of the European theater also favored the American approach.

In the Bokeage country of Normandy, with its narrow lanes and dense hedge rows, long range gunnery meant little. Combat occurred at close range, often under 500 yardds, where the Sherman’s stabilized gun and faster rate of fire provided advantages. In the forests of the Arden, mechanical reliability determined survival more than armor thickness.

in the open plains of France post breakout. Speed and fuel efficiency allowed Shermans to pursue retreating German forces while heavier panzers broke down or ran out of fuel. The allies also enjoyed total air superiority by mid 1944. German tank columns moving in daylight were strafed by P47 Thunderbolts and RAF Typhoons armed with rockets.

The skies belonged to the Allies, and that negated much of the advantage German armor might have had on the ground. A Tiger could destroy five Shermans, but if it was caught in the open by air attack, it died like any other vehicle. American armored tactics evolved to exploit these realities. Sherman’s advanced in combined arms teams, tanks, infantry, engineers, artillery, and air support all coordinated.

If a German strong point resisted, the Americans did not charge headlong. They called in artillery. They waited for air strikes. They flanked. They used their numerical superiority to isolate and destroy pockets of resistance methodically. It was not elegant, but it was devastatingly effective. The greatest advantage of the Sherman was not its gun or its armor.

It was the fact that it could be anywhere, anytime, in any number. Consider the logistics. A Sherman weighed 30 tons. Transporting one required specialized rail cars, cargo ships with reinforced decks, and heavy trucks for short distance movement. The United States needed to move thousands of Shermans from factories in Michigan and Pennsylvania to ports on the east coast, then across the Atlantic where German yubot hunted convoys, then to ports in Britain, North Africa, or Italy, and finally to the front lines.

This was accomplished through the most extensive logistics operation in history. The US Navy’s escort carriers and destroyers protected convoys. Liberty ships, mass-roduced cargo vessels, carried tanks across the ocean. In Britain, massive staging areas near Portsmouth and Southampton stored thousands of vehicles awaiting D-Day.

Repair depots were established across the theater, staffed by mechanics trained to work on Shermans specifically, and the Shermans kept arriving. In the month before D-Day, over 5,000 tanks were stockpiled in southern England. After the invasion, they were landed directly onto the beaches via LSTs. Landing ships designed to carry tanks and drive them straight onto shore.

Within weeks, entire armored divisions were operational in France, supplied by a logistics chain that stretched back across the Atlantic without a single break. Contrast this with Germany. By 1944, the Wehrmacht could barely move tanks from factories to the front. Allied bombing had shattered rail networks.

Fuel shortages meant Panthers sat in depots waiting for gasoline that never came. When a Panzer division was destroyed, its replacement took months to organize and was often a shadow of the original, equipped with whatever vehicles were available rather than a standardized force. The Sherman’s mechanical reliability was central to this logistical triumph.

A tank that breaks down constantly is a drain on supply lines. It requires spare parts, specialized tools, and time. The Sherman built with automotive grade components rarely broke. Its tracks lasted thousands of miles. Its engine could run on standard gasoline. Field maintenance was straightforward enough that crew members could perform basic repairs themselves.

This meant that a Sherman division could advance hundreds of miles, fighting continuously without losing cohesion. German Panzer divisions, by contrast, often lost half their strength to mechanical failure before ever engaging the enemy. In the race across France in summer 1944, American armored units covered 400 miles in three weeks, liberating town after town. their Sherman still running, still fighting. The Germans could not match that endurance.

They had better tanks, but they did not have enough, and they could not keep them moving. The logistical superiority of the Allies embodied in the humble Sherman was as decisive as any battle. It was the unglamorous work of supply officers, mechanics, ship crews, and factory workers that made the Sherman unstoppable.

The tank itself was merely the tip of a spear forged from American industrial might. And that spear reached into the heart of occupied Europe without pause or mercy. June 6th, 1944. Omaha Beach, Normandy. The ramps drop on the landing craft. saltwater and diesel smoke. Men and machines surge forward into chaos.

Among them, Shermans, specially modified for the invasion. Some with flotation screens, others with dozer blades or flamethrowers. They grind up the sand, tracks spinning, engines roaring over the sound of machine gun fire and artillery. A Sherman equipped with a duplex drive system. A canvas flotation screen waddles ashore half submerged looking absurd until its tracks find purchase and it surges forward.

Turret traversing 75 mm gun spitting fire at German bunkers. Another Sherman hit by an anti-tank round burns on the beach. Black smoke rising into the gray morning. But more keep coming. always more. By nightfall, despite catastrophic losses, the Allies have secured a foothold. And with them, the Shermans. They do not pause. They do not wait for perfect conditions.

They push inland, tearing through hedge, supporting infantry as they clear villages, engaging German armor wherever it appears. The invasion, the largest amphibious operation in history, succeeds in part because the Sherman can be landed, can be deployed, and can fight immediately without extensive preparation. The hedge of Normandy are a nightmare.

Each field is bordered by ancient earthn walls topped with dense vegetation creating natural fortifications. German infantry wait an ambush with punzer foya handheld anti-tank rockets. A Sherman advancing down a narrow lane is a sitting target. The first weeks in Normandy are brutal. American tankers learn to hate the hedge, to fear the sudden explosion that comes without warning, the flame that fills the crew compartment in seconds.

But the Americans adapt. Engineers weld steel teeth onto the front of Sherman’s rhino tanks that can tear through hedge rows instead of climbing over them. Tactics evolve. Infantry scouts ahead, marking enemy positions. Engineers blow gaps. Shermans surge through in groups, suppressing resistance with machine gun fire before the main gun target specific threats. It is slow, grinding, costly work.

But it is progress, and the German defenders outnumbered and outgunned begin to crack. The Panzer divisions sent to contain the invasion. 21st Panzer, 12th SS Panzer, Panzer Lair, fight with desperate courage. But they cannot be everywhere. A Panther hidden in a hedro can destroy three Shermans. But then it must retreat because there are 10 more Shermans coming and Allied fighter bombers circle overhead waiting for a target.

The Germans fight brilliant defensive actions and are overwhelmed anyway. By the end of June, the Allies have landed over 850,000 men and 150,000 vehicles, including thousands of Shermans. The beach head is secure, expanding, unstoppable. German counterattacks fail. The Panzers attack in company strength when they need division strength.

They destroy Allied tanks by the dozens, but cannot break the line because the line replenishes itself faster than it can be destroyed. In early July, the Americans prepare Operation Cobra, the breakout from Normandy. The plan is simple and brutal. Saturate a narrow front with air power and artillery, then pour armored divisions through the gap before the Germans can react.

It is a gamble that depends on speed, coordination, and having enough tanks to exploit any success. July 25th, 1944, 1100 hours. The bombardment begins. Over 1/500 heavy bombers carpet bomb a 5m stretch of German defensive line near S. Low. The Earth convulses. Entire infantry companies vanish. German survivors stumble from craters, deafened, bleeding, broken.

Then the artillery opens. Thousands of guns firing in sequence. A wall of steel descending on what remains of the German positions. And then the Shermans. They come in columns, company after company, regiment after regiment. The second and third armored divisions, the fourth and sixth armored divisions.

Hundreds upon hundreds of Shermans advancing on a front barely three miles wide. The bombardment has stunned the defenders, shattered their communications, destroyed their anti-tank guns. The Shermans do not pause to engage. They drive through over past the remnants of German resistance. A few Panthers emerge from hidden positions.

Firing desperately, they destroy Shermans 1, two, five. But for every Sherman stopped, three more bypass the threat and infantry with bazookas close in from the flanks. The Panthers fight until they are out of ammunition or their crews are dead. There is no retreat because there is nowhere to retreat to. The American tide is everywhere.

By July 27th, the German line has collapsed. The second armored division is 20 mi behind what was the front line two days ago. German units cut off and surrounded. Surrender in groups. Entire battalions cease to exist. The Wehrmacht in Normandy, which had held the Allies at bay for 7 weeks, disintegrates in 72 hours. The Shermans do not stop.

They race south then east. Engines running day and night. crews rotating sleep shifts while the tanks keep moving. They liberate town after town. Coutses of ranches lemon. The German army which once conquered France in six weeks is now fleeing France, desperately trying to escape encirclement.

And everywhere they turn, there are Shermans waiting an ambush, blocking roads, crushing retreating columns. August 1944. The file’s pocket. The breakout from Normandy has trapped the bulk of the German 7th army and the fifth panzer army in a shrinking pocket near the town of Fales. Canadian forces push from the north.

American forces swing east and north, closing the gap. British and Polish units attack from multiple directions. The Germans, realizing the trap too late, attempt to fight their way out. It is already too late. The roads are clogged with retreating German forces, tanks, trucks, horsedrawn wagons, soldiers on foot. They move at night, trying to avoid Allied aircraft.

But the sky belongs to the Allies, and dawn brings typhoons and thunderbolts that strafe anything that moves. The columns burn. The roads become graveyards. And then the Shermans arrive. The fourth armored division cuts the escape route near Argentan. The second armored division blocks roads to the east. The first Polish armored division seizes high ground overlooking the pocket.

Everywhere Shermans take up firing positions, their guns trained on the chaos below. August 19th, 1944. The pocket closes. German units trapped inside attempt breakouts. Panzer divisions that once numbered hundreds of tanks now field a dozen, maybe two dozen operational vehicles. They attack in desperation. Tigers and Panthers leading infantry assaults against Sherman positions. The fighting is vicious. Close range without quarter.

A Tiger emerges from a tree line. Its 80 lm gun destroying two Shermans before they can traverse their turrets. But five more Shermans flank from the right. Their 75 mm guns hammering the Tiger’s thinner side armor. One shot penetrates. The Tiger shuddters, stops, smoke pouring from the engine deck.

The crew bails out. They do not get far. This scene repeats across the pocket. German armor once feared across Europe dies in groups. Not because the individual tanks are inferior. They are not. But because there are too many Shermans, too many angles of attack, too much coordinated fire.

A Panther can kill three Shermans and still die to the fourth. The mathematics are inescapable. The German soldiers trapped in the pocket call it the corridor of death. Artillery rains down constantly. Fighter bombers circle like vultures, dropping bombs on anything that moves. And everywhere the Shermans advance, grinding forward, crushing resistance yard by yard.

There is no mercy here. No room for surrender. Just the relentless mechanical brutality of industrial warfare. Inside the pocket, German commanders issue feutal orders. Units that no longer exist, are told to counterattack. Artillery batteries that have been destroyed are ordered to provide support.

The command structure, so efficient in victory, collapses in defeat. Radios go silent. Runners do not return. Officers make decisions for their own men, trying to save whoever they can. Some German units manage to escape through a narrow gap near Shamba before it closes completely.

They leave behind everything, tanks, trucks, guns, supplies. They flee on foot, discarding helmets and weapons, caring only about survival. Those who remain fight to the end or surrender when resistance becomes meaningless. By August 24th, the Filet’s pocket ceases to exist. Over 50,000 German soldiers are captured. Another 10,000 are dead.

The wreckage is apocalyptic. Thousands of destroyed vehicles litter the roads, many still burning. Horses killed by the thousands bloat in the summer heat. The smell is unbearable for miles. And among the wreckage, over 500 destroyed German tanks and assault guns. Panthers and tigers that were supposed to stop the Allies now just smoking hulls.

Some destroyed in combat, others abandoned when they ran out of fuel or broke down. All of them silent monuments to the failure of quality over quantity. The Shermans that destroyed them keep moving. Some are damaged, tracks blown off or armor penetrated, but most are intact. Their crews exhausted but alive.

Their tanks still operational. They refuel from jerry cans brought up by supply trucks. They reload ammunition. They repair minor damage in the field. And then they advance again eastward toward the German border. The Vermach’s forces in France are shattered.

The Panzer divisions that held Normandy for seven weeks are destroyed as coherent formations. The survivors retreat in chaos, abandoning equipment, trying to reach the Sief Freed line before the Allies catch them. But the Shermans are faster. They liberate Paris on August 25th. They cross the sand. They drive through Belgium, liberating Brussels. On September 3rd, the German high command watches in horror as their defensive line collapses. Reports flood in.

Another city lost, another division destroyed, another 100 tanks abandoned. The Shermans, once mocked as inferior, are everywhere. They do not stop. They do not slow. They have become the face of Allied armored power, the symbol of Germany’s inevitable defeat. In September 1944, American and British forces reach the German border.

Some units penetrate into Germany itself before supply lines finally stretch too thin and the advance halts. The Sherman crews, veterans now of 500 miles of combat, look toward the east. They have proven something fundamental. Not that the Sherman was the best tank, but that it was enough. And when you have enough, when you can replace every loss and still have reserves, you do not need to be the best. The mockery is over.

The German tankers who survive speak of the Shermans with respect, sometimes with dread. They speak of the noise, dozens of engines, all running, all advancing, the sound growing louder until it drowns out thought. They speak of the inevitability destroying one Sherman only to see two more crest the hill. They speak of the moment they realized the war was lost.

That all their skill and courage meant nothing against an enemy who could absorb any loss and keep attacking. The Sherman had crushed them, not by being better, but by being there in overwhelming numbers, supported by endless resources, crewed by men who learned quickly and fought tenaciously. The Germans had mocked the Sherman because they thought wars were won by superior technology.

They learned too late that wars are won by the side that can sustain the fight longer than the enemy can resist. By the end of 1944, over 40,000 Shermans had been produced. They fought in France, in Italy, in Belgium, in the Philippines. They supported Soviet offensives in the East. They led British advances in Burma.

The Sherman was not confined to one theater or one army. It was the universal tool of Allied victory, present at every decisive battle, reliable in every climate, adaptable to every tactical challenge. The climax of the Sherman story was not a single battle. It was the accumulation of a thousand battles where German armor, outnumbered and exhausted, fought brilliantly and lost anyway.

It was the moment when German commanders stopped planning counter offensives and started planning retreats. It was the slow, grinding realization among Vermach veterans that the American tanks they once laughed at would be the last thing many of them ever saw. The cost was staggering.

Between 1944 and 1945, the US Army lost approximately 8,000 Shermans in combat in the European theater, 8,000 tanks, 32,000 crew positions. Not all crew members died. Many survived hits, bailed out, were wounded or captured, but thousands did not. Burned alive when ammunition ignited, crushed when turrets collapsed, killed instantly by penetrating rounds that turned the interior into a shrapnel storm.

The Sherman earned a grim nickname among its crews, Ronson, after the cigarette lighter company, whose slogan was lights first time every time. The porn’s joke was bitter. A Sherman hit in the wrong place near the ammunition stowage in the sponssons could brew up in seconds, flames engulfing the crew compartment before anyone could escape.

Later models moved ammunition storage to the hull floor and added water jackets, reducing this risk. But the nickname stuck, a reminder of the price paid for numerical superiority. German losses were proportionally worse, but harder to quantify precisely. The Vermach lost approximately 6,000 tanks and assault guns on the Western Front between D-Day and Germany’s surrender.

But unlike the Americans, the Germans could not replace them. Every Panther destroyed was one fewer in the inventory. Every Tiger lost was a permanent reduction in combat power. By early 1945, some Panzer divisions fielded fewer than 20 operational tanks, a fraction of their authorized strength. The human toll on the German side was catastrophic.

Experienced Panzer crews, veterans of years of combat, died in their vehicles when there was no fuel to retreat and no ammunition to continue fighting. Young replacements trained for weeks instead of months were thrown into combat and killed in their first engagement. The institutional knowledge that had made the Panzer forces so effective, the tactics, the coordination, the battlefield awareness evaporated as the veterans died and could not be replaced.

But numbers alone do not tell the full story. The Sherman’s greatest impact was strategic and psychological. It broke the myth of German armored invincibility. It demonstrated that industrial capacity was as decisive as tactical brilliance. It forced the Vermach into a defensive posture from which it never recovered.

After the Filet’s pocket, German armored forces in the west ceased to exist as a coherent offensive threat. The Panzer divisions were rebuilt, refitted with whatever tanks could be scraped together and thrown into defensive battles. At Aken, at Mets, at the Herkin Forest, they fought with desperate courage. They inflicted heavy casualties on Allied forces, but they could not win.

They could only delay. In December 1944, Germany launched its last major offensive in the West, the Battle of the Bulge. Over 200,000 German troops, supported by hundreds of panzers, including the new King Tiger, attacked through the Arden Forest. The offensive achieved complete surprise, smashing through thinly held American lines, capturing thousands of prisoners, advancing 50 miles in a week. And then it stalled. Fuel ran out.

Supply lines were cut by American air power once the weather cleared. Allied reinforcements, including entire armored divisions equipped with Shermans, arrived and contained the breakthrough. By January 1945, the German offensive had collapsed. The panzers that penetrated deepest were abandoned, out of fuel. their crews retreating on foot.

The Bulge was Germany’s last gasp, and the Sherman helped ensure it failed. The Shermans that fought in the Bulge were often upgraded models. The M4 A3E8, known as the Easy8, featured improved suspension, wider tracks, and a 76 millm gun that could penetrate Panther armor at combat ranges.

These newer Shermans were more than adequate to deal with German armor, and there were hundreds of them. The Germans fielded their heaviest tanks, King Tigers with 80 to guns, and armor so thick that most Allied weapons were ineffective frontally. But there were only a few dozen King Tigers, and they broke down constantly, victims of their own excessive weight and complexity.

The aftermath of the Bulge exemplified the Sherman’s role in Allied victory. It was not the tank that won individual duels. It was the tank that kept the front moving, that could be repaired and returned to combat, that arrived in such numbers that losing 50 still left hundreds in reserve. The Germans could not match this.

They had run out of fuel, out of tanks, out of trained crews, out of time. By March 1945, Allied forces crossed the Rine. Shermans rolled into the industrial heartland of Germany. The factories that had once produced Panthers and Tigers, now silent or destroyed by bombing. German resistance crumbled. Entire armies surrendered.

The once mighty Vermach, starved of fuel and ammunition, defended with obsolete equipment and teenage conscripts. The Sherman’s War did not end in Europe. In the Pacific, marine and army units used Shermans in island assaults, their 75mm guns proving devastating against Japanese bunkers.

In the Philippines, Sherman supported infantry in brutal urban combat. They were there at Euima, at Okinawa, grinding forward under fire, supporting Marines who measured progress in yards. The Sherman adapted to every theater, every challenge, every enemy. When the war ended in May 1945, the Sherman’s production total exceeded 49,000 units.

49,000 tanks, more than all German tank production during the entire war, more than the Soviet T34 in the same period. It was the most produced tank of World War II by the Western Allies, and its ubiquity defined Allied armored warfare. But the Sherman story did not end in 1945. It fought in wars for decades afterward.

The Israeli Defense Forces used Shermans in 1948, 1956, 1967, and even 1973, upgraded with modern guns, diesel engines, and improved armor. Arab nations fielded Shermans. South American armies used them. The tank designed for World War II remained in frontline service for 30 years, a testament to its reliability and adaptability. The debates about the Sherman began almost immediately after the war.

Veterans criticized its armor and gun, claiming American tankers were sacrificed because the military refused to field heavier tanks. The M26 Persing, a heavy tank with a 90mm gun and thicker armor, arrived in Europe in February 1945, too late to matter. Some argued it should have been deployed earlier, that American tankers deserved better protection.

But this criticism misses the strategic context. The Persing weighed 46 tons, too heavy for many bridges, and incompatible with existing logistics. It was mechanically complex, prone to breakdown, difficult to transport overseas in large numbers. Had the US focused on producing Persings instead of Shermans, fewer tanks would have reached the front and the war might have lasted longer.

The Sherman was not perfect, but it was what the Allies needed, a tank they could produce, transport, and maintain in overwhelming numbers. German veterans interviewed after the war offered a more nuanced perspective. They acknowledged the Sherman’s weaknesses, thin armor, inadequate gun in later stages, but respected its reliability and the sheer number deployed.

One Panzer officer remarked that the Sherman was a mediocre tank, but there were always 10 of them. Another noted that we could destroy them easily, but they kept coming, and we ran out of ammunition before they ran out of tanks. This was the essence of the Sherman’s impact. It was not designed to be superior in individual combat.

It was designed to ensure that Allied armored forces could attack anywhere at any time with enough tanks to guarantee success through attrition. The Germans bet on quality. The Americans bet on quantity and in total war, quantity won. The psychological impact on German forces cannot be overstated. By late 1944, Wehrmacht soldiers dreaded the sound of approaching Shermans.

Not because a single Sherman was terrifying, but because it was never just one. The sound meant dozens were coming, supported by infantry, artillery, and air power. It meant the front was about to be overrun. It meant retreat or death. The tank that German propagandists once ridiculed in news reels became the symbol of inevitable defeat. For American soldiers, the Sherman was both savior and coffin.

It protected them from small arms and artillery fragments. It provided mobile firepower that could suppress enemy positions. But it also burned when hit, trapping crews inside. The tankers who survived the war carried the memory of friends who did not escape, who died screaming as flames consumed them.

They were proud of what they accomplished, but haunted by the cost. The Sherman also represented a broader truth about American industrial power. The United States entered World War II with virtually no modern armored force. Within three years, it produced more tanks than any nation in history and deployed them on six continents.

The factories that built automobiles retoled to build tanks. The workers who assembled cars learned to assemble weapons of war. And they did it faster, more efficiently than anyone thought possible. This industrial mobilization extended beyond tanks. The same philosophy applied to aircraft. Over 300,000 produced during the war to ships.

Thousands of Liberty ships, carriers, destroyers to ammunition to vehicles to every tool of modern warfare. The Sherman was one part of a system that overwhelmed the Axis through sheer material superiority. Germany and Japan, for all their tactical skill and technological innovation, could not compete with an enemy that could replace losses faster than they could inflict them.

the legacy of the Sherman-shaped post-war tank design. The Soviets, who received thousands of Shermans under Lend Lease, noted its reliability and ease of maintenance, principles they incorporated into later T-series tanks. The British continued using Shermans into the 1950s, upgrading them with better guns and engines.

The Americans learned that speed, reliability, and producability mattered more than maximum armor or firepower. Lessons that influenced the M48 and M60 tanks of the Cold War. But perhaps the most important legacy was doctrinal. The Sherman proved that wars are not won by individual weapons but by systems, logistics, industrial capacity, training, coordination. These determined victory more than any single piece of technology.

The Germans built better tanks. The Americans built a better war machine. And the Sherman, humble and derided as it was, embodied that machine’s power. By 1950, most Shermans in US service were retired or mothballled. They sat in depots, relics of a war won at tremendous cost.

But around the world, they continued fighting, upgraded, and repurposed, a testament to a design that prioritized practicality over perfection. The tank that German crews mocked in 1943 became the tank that defined Allied victory in 1945. and its descendants fought in wars for another generation. The mockery had been silenced not by words, but by the relentless grinding of tracks across Europe, by the thunder of 75 liil guns, by the sheer unstoppable presence of thousands upon thousands of Shermans advancing toward Berlin. The Germans learned what industrial warfare truly

meant. And the lesson was written in steel and fire, taught by a tank they should never have underestimated. Wars are not won by the best weapons. They are won by the side that can sustain the fight long enough to break the enemy’s will and capacity to resist. The M4 Sherman, for all its flaws, embodied this truth.

It was not the most powerful tank of World War II, not the most heavily armored, not the most feared in single combat, but it was the most important. It was the tank that could be everywhere, that could be produced faster than it could be destroyed, that could carry the weight of Allied strategy across two oceans and three continents.

It was the tank that transformed American industrial might into battlefield dominance. The Germans mocked it because they measured success in individual duels, in technical specifications, in the superiority of their engineering. They built magnificent machines, the Tiger, the Panther, technological marvels that dominated battlefields when they worked.

But they could not build enough of them. They could not keep them running. They could not replace the crews who died inside them. The Americans built a tank that was good enough. And then they built 49,000 of them. They shipped them across oceans, landed them on hostile beaches, drove them through hedgeros and forests and deserts and cities.

They lost thousands and replaced them within weeks. They adapted the design continuously, learning from every battle, improving without halting production. They created not just a weapon, but a system, logistics, maintenance, training, doctrine that made the Sherman unstoppable, not because it was superior, but because it was relentless.

The Sherman story is the story of World War II itself. Not a tale of heroes and villains, but of industrial nations locked in total war, where victory went not to the bravest or the most skilled, but to the side that could endure the longest. The Germans fought with courage and tactical brilliance until the very end. But courage cannot stop a tide.

Brilliance cannot overcome mathematics. And the Sherman was the physical manifestation of that mathematical inevitability. In the end, the mockery ceased because the truth became undeniable. The Shermans kept coming across the beaches of Normandy, through the streets of French villages, over the Rine, into the heart of Germany.

They came in hundreds and thousands, crewed by men who learned quickly and fought hard. Supported by a nation that would not stop producing them until the war was won. The Germans mocked American tanks, the M4 Sherman crushed them by the hundreds. And in that crushing, it wrote the final chapter of the Third Reich’s ambitions.

not with a single devastating blow, but with the slow, inexurable grinding of industrial warfare waged by a democracy that refused to lose. The lesson remains, underestimate your enemy at your peril, especially when that enemy commands the largest industrial economy in human history and possesses the will to use it. The Sherman was never supposed to be the best tank. It only needed to be enough.

And in the arithmetic of total war, enough when multiplied by thousands becomes everything.

News

CH2 THE FARMER’S TRAP THAT SHOCKED THE THIRD REICH: How One ‘Stupid Idea’ Annihilated Two Panzers in Eleven Seconds and Changed Anti-Tank Warfare

THE FARMER’S TRAP THAT SHOCKED THE THIRD REICH: How One ‘Stupid Idea’ Annihilated Two Panzers in Eleven Seconds and Changed…

CH2 THE SIX AGAINST EIGHT HUNDRED: The Guadalcanal Miracle That Even Japan Called ‘Witchcraft’ — How a Handful of Black Marines Turned a Jungle Death Trap into the Most Mysterious Stand of the Pacific War

THE SIX AGAINST EIGHT HUNDRED: The Guadalcanal Miracle That Even Japan Called ‘Witchcraft’ — How a Handful of Black Marines…

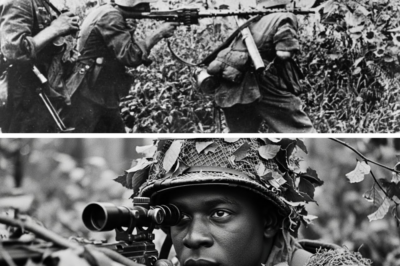

CH2 THE INVISIBLE GHOST OF NORMANDY: How One Black Sharpshooter’s Ancient Camouflage Turned Him Into the Wehrmacht’s Worst Nightmare – Germans Never Imagined One Black Sniper’s Camouflage Method Would K.i.l.l 500 of Their Soldiers

THE INVISIBLE GHOST OF NORMANDY: How One Black Sharpshooter’s Ancient Camouflage Turned Him Into the Wehrmacht’s Worst Nightmare – Germans…

CH2 THE PLANE THEY CALLED USELESS — The ‘Flying Coffin’ That HUMILIATED Japan’s Zero and TURNED the Pacific War UPSIDE DOWN

The Forgotten Fighter That Outclassed the Zero — The Slow Plane That Won the Pacific” January 1942. The Pacific…

CH2 ‘JUST A PIECE OF WIRE’ — The ILLEGAL Field Hack That Turned America’s P-38 LIGHTNING Into the Zero’s WORST NIGHTMARE and Changed the Pacific War Forever

‘JUST A PIECE OF WIRE’ — The ILLEGAL Field Hack That Turned America’s P-38 LIGHTNING Into the Zero’s WORST NIGHTMARE…

CH2 THE ENEMY WHO LANDED BY MISTAKE: How a Wounded Japanese Zero Pilot Had To Land Onto a U.S. Aircraft Carrier

THE ENEMY WHO LANDED BY MISTAKE: How a Wounded Japanese Zero Pilot Had To Land Onto a U.S. Aircraft Carrier…

End of content

No more pages to load