They Mocked His “Pistol Only Crawl” — Until This Brooklyn Soldier Took Out a Machine Gun Crew on D-Day And Shattered Every Army Doctrine They Ever Taught Him!

The Atlantic surf crashed over Private First Class Vincent Gallagher’s legs as he pressed himself into the wet, iron-tasting sand. June 6, 1944. 6:47 a.m. Omaha Beach. The morning was gray, cold, and alive with the roar of artillery and machine gun fire. Men of the 116th Infantry Regiment, 29th Division, screamed, fell, and disappeared into pink-stained water, swallowed by the merciless German MG42s entrenched in the bluffs ahead.

Thirty yards in front of Gallagher, a German machine gun crew methodically cut down every American soldier who dared stand. Forty-two men had already died in just eleven minutes. Officers shouted, tried to coordinate fire and maneuver assaults, but every tactic failed. Suppressing fire didn’t suppress anything. Rushing forward was a death sentence.

Gallagher lay in the sand, face pressed into the grit, staring at the gun and listening to its rhythm. Four seconds, five, six… between bursts, the machine gunner acquired a new target. Too little time to run. Too little time to charge. But maybe enough to crawl three feet, then flatten again.

He thought of Red Hook, Brooklyn. The waterfront, the docks, the alleys, the street fights. He had learned early that standing tall meant getting your teeth kicked in. You survived by staying low, moving fast when no one expected it, closing distance, and striking first. And he had a weapon no one else had thought to bring: his .45 Colt M1911. While his comrades obeyed regulations and relied on rifles in the surf, Gallagher carried a pistol—an idea scoffed at by his officers, dismissed as a street-smart novelty.

Thirty years of dockside discipline and street-fighting instinct merged in that moment with military training. Gallagher’s father had hoisted steel cables on the docks while his mother washed laundry in the flat irons of Red Hook. Vincent had quit school at fifteen to work the piers, learning leverage, precision, and how to stay low under crushing loads. But the streets had taught him survival when the odds were impossible. Now, all that knowledge was about to be tested against the finest German machine gunners in Europe.

He remembered his uncle Sheamus’s voice: “Get within ten feet. Accuracy doesn’t matter. Just point and pull until they stop moving.” That wisdom had seemed quaint back in Brooklyn. On Omaha Beach, it was all that stood between him and death.

Around him, men screamed. Sergeant Hoff, a dairy farmer from Wisconsin, had been hit two minutes after leaving the landing ramp. Lieutenant Brennan floated face down in the surf. Thirty-eight men of C Company, 116th Infantry, lay dead or dying in fifty yards of blood-soaked sand. The MG42 continued its deadly sweep.

Gallagher began his crawl. Not the army’s high crawl or low crawl, drilled for weeks at Slapton Sands, England. This was the crawl of Red Hook alleys, shadows under lamplight, slipping past danger while hearts pounded and knives were close. He advanced, three feet at a time, flattening when the machine gun barked, crawling over comrades who had already fallen. Corporal Jack Mitchell, Private Tommy Walsh—they were all corpses now, markers of failed doctrine. Gallagher ignored them. He had a mission.

Twenty-five yards. Thirty. He could hear German voices. Calm. Precise. Professional. They weren’t panicking. They were executing, calculating, prepared. Forty yards. Fifty. Sixty. Sand, surf, gear, and adrenaline weighed him down, but he pressed on.

Then he saw it: a small blind spot in front of the reinforced concrete emplacement. Dead ground, fifteen feet wide, completely out of the MG42’s firing arc. He angled his crawl into it, now within twenty-five yards of the gun, close enough to smell the German tobacco and hear boots scraping on concrete.

Ten yards. Nine. Eight. He rose into a crouch, gripping the Colt M1911 like his uncle had taught him, tight to his body, point shooting instinctively. Seven yards. Six. Five. Four. The bunker’s interior was clear. Four Germans, unaware of the one American crawling toward them: the gunner, the assistant feeding the belt, an NCO scanning the beach, a boy stacking ammunition.

Continue below

At 6:47 a.m. on June 6th, 1944, Private First Class Vincent Gallagher dragged himself through blood soaked sand on Omaha Beach with nothing but a .45 pistol and a plan every officer called suicide. 30 yards ahead, a German MG42 machine gun nest had killed 42 men in the last 11 minutes.

Every soldier who stood was cut down. Every advance was shredded. In the next 18 minutes, Gallagher would crawl within 8 ft of that position, kill four Vermached soldiers with seven shots, and permanently change US Army close combat doctrine. This is the story of how a Brooklyn doc worker street fighting technique became standard infantry training.

The bodies formed a line in the sand. Each corpse marked where a man had tried to advance, tried to rush the position, tried to do what the training manual said. Fire and maneuver, suppressing fire, coordinated assault, all of it useless against the MG42, tearing through dog green sector at 120 rounds per minute. Gallagher pressed his face into wet sand that tasted like iron and salt.

Surf crashed over his legs. The machine gun barked in short, precise bursts. German discipline. They weren’t panicking, weren’t wasting ammunition, just methodically killing anyone who moved. He counted the rhythm between bursts. 4 seconds, 5 seconds, 6 seconds. while the gunner acquired a new target.

Not enough time to run, not enough time to charge, but maybe enough time to crawl forward 3 ft before flattening again. His platoon sergeant, a dairy farmer from Wisconsin named Sergeant Hoff, had taken half his face off 2 minutes after the ramp dropped. Lieutenant Brennan, their company commander, was floating face down in the surf.

38 men from Ca Company, 116th Infantry Regiment, lay dead or dying in a 50-yard stretch of beach. And that MG42 just kept firing. Gallagher had one advantage nobody else recognized. He’d grown up fighting in ways the army didn’t teach, and he’d brought his 45 pistol ashore when regulations said riflemen didn’t need sidearms in the initial assault.

That single act of disobedience was about to save what remained of his company. Vincent Gallagher was born in Red Hook, Brooklyn in 1921, the third son of a long shoreman who worked the Atlantic Basin docks. His father unloaded cargo 12 hours a day. His mother took in laundry. Vincent quit school at 15 to work alongside his old man, hooking steel cables to cargo nets and learning that one mistake could crush you under three tons of freight. The docks taught practical skills.

How to move heavy weight, how to use leverage, how to stay low when cargo swung overhead. But Red Hook’s streets taught something else, how to fight when you couldn’t run. How to win when you were outmatched. Vincent wasn’t big. 5’9″, 160 lb, soaking wet. The Irish and Italian gangs that ran the waterfront didn’t care about his size.

They cared whether you could handle yourself when someone came at you with a pipe or a knife. Vincent learned to fight from a crouch, to move low, to get close before the other guy expected it. Standing tall in a street fight meant getting your teeth kicked in. The winner stayed low, closed distance fast, and hit first.

He also learned to use a pistol, not from the army, from his uncle Sheamus, who’d carried a 38 revolver during the dock strikes of 1934. Sheamus taught him something the military never emphasized. A pistol wasn’t a long range weapon. It was a close-range certainty. “Get within 10 ft,” Sheamus said. “And accuracy don’t matter. You just point and pull until they stop moving.

” Vincent enlisted 3 weeks after Pearl Harbor. The 116th Infantry Regiment welcomed him in February 1942. He was a decent shot with an M1 Garand, excellent with a bayonet and exceptional at one thing the army didn’t test, moving through dangerous ground without getting killed. By May 1944, the 116th had trained for amphibious assault for 26 months.

They’d rehearsed beach landings at Slapton Sands in England. They’d practiced fire and maneuver tactics. They’d memorized doctrine that assumed suppressing fire would pin enemy positions while infantry advanced in rushes. Nobody mentioned what happened when suppressing fire didn’t work.

When the enemy position was too well protected, when every man who stood up died. The Hunheder 16th Infantry hit Omaha Beach in the first wave at 6:30 a.m. Gallagher’s company, Sea Company, landed at Dog Green Sector directly in front of the fortified Verville draw. German defensive positions had clear fields of fire across 400 yardds of beach. The Vermach had spent two years preparing these defenses.

Concrete bunkers, reinforced pill boxes, interlocking fields of fire. The MG42 machine gun that would define Gallagher’s morning sat in a position engineers had designed specifically to kill men on that exact stretch of sand. The first soldier off Gallagher’s landing craft was Private Firstclass Eddie Sullivan from Boston.

The MG42 caught him in the chest before his boots hit water. He dropped without making a sound. Corporal Anthony Ramirez, a mechanic from El Paso, made it three steps before tracers cut through his midsection. He screamed for 7 seconds before the water took him. Gallagher went over the side into four feet of surf.

Cold Atlantic water hit him like a wall. He kept his rifle above his head and waited forward. Men were dying around him so fast he couldn’t process individual deaths. Just bodies, just blood turning the water pink. He made it to the sand, dropped flat. The machine gun traversed left to right. systematic sweeps that caught anyone who moved.

Sergeant Hoff tried to organize a squad to rush forward. “On me! On me!” the MG42 answered. Hof went down along with five men who’d stood to follow him. Gallagher pressed himself into the sand. He could see the position now. A reinforced concrete imp placement built into the base of the seaw wall 70 yard inland. The gun barrel protruded through a narrow firing slit.

Smoke drifted from the muzzle. German voices shouted commands inside the bunker. Lieutenant Brennan’s voice cut through the chaos. Covering fire. Covering fire on that position. Rifles cracked. Bullets sparked off concrete. The machine gun didn’t even pause. It fired another burst and two men from second platoon collapsed. Then Brennan tried to lead by example.

He rose to one knee, pointing toward the bunker. Follow me. We’re going. The burst caught him across the throat. He fell backward into the surf. That’s when Gallagher looked at his rifle and made a decision. The M1 Grand was an excellent weapon at 300 yd.

Accurate, reliable, powerful, completely useless on this beach. Every man with a rifle was pinned down. The Germans weren’t exposed enough to hit from this range, and anyone who stood to get a better angle died before they could sight in. He thought about the docks, about fighting close, about not giving the other guy space to work. The MG42 fired again.

Three men from third platoon tried to advance in a fire and maneuver drill exactly like training. The ones providing covering fire barely made the Germans flinch. The ones trying to move got shredded. Gallagher unholstered his .45 pistol. It was a Colt M19 WA1. Standard Army issue that most riflemen didn’t carry in assault. He’d brought it anyway because Uncle Sheamus’s voice had been in his head.

Better to have it and not need it. Nobody around him was paying attention. They were all focused on that machine gun, on surviving the next burst, on not being the next one to die. Gallagher started crawling forward. Not the crawl they’d taught in basic training. Not the high crawl or the low crawl from the manual.

This was the crawl he’d learned as a kid. Slipping through red hook alleys, staying below sight lines, moving when nobody was looking. Flat as a shadow, slow, patient. The machine gun fired. He froze. The burst ended. He crawled forward 3 ft. Sand pressed against his face. Water soaked through his uniform. The weight of his gear dragged at him. He ignored it and crawled.

He passed Corporal Jack Mitchell, who’d been killed trying to throw a grenade that detonated 20 yards short. He passed Private Tommy Walsh face down in pink water. He didn’t stop, didn’t look at their faces, just kept crawling 20 yards, then 25. The machine gun kept firing at targets behind him.

The Germans hadn’t noticed one man crawling through their kill zone because one man crawling looked like one more corpse. 30 yards. He could hear German voices clearly now. Calm professional commands. The gunner calling targets. The assistant feeding belts. They were working smoothly, efficiently. No panic whatsoever.

Gallagher’s hands shook, not from fear, from understanding what he had to do next. He was about to disobey every piece of infantry doctrine he’d learned. The manual said, “You didn’t attack machine gun positions alone. You didn’t assault prepared defenses with a pistol. You didn’t crawl to point blank range and hope surprise was enough.” But the manual was written by men who weren’t bleeding to death on Omaha Beach.

He kept crawling 40 yards, 50 yards. He could see bodies stacked in front of the position now. Men who’ tried to rush it. Men who’ died following doctrine. Their blood ran down the sand in dark streams. The smell of cordide and copper was overwhelming. The MG42 barked again. Somewhere behind him, someone screamed. The gun traversed back to the left.

The crew was focused outward, scanning for the next group of soldiers trying to advance. Gallagher reached 60 yards, then 65. His heart hammered against his ribs. Sweat mixed with seaater on his face. He gripped the 45 pistol so hard his knuckles were white. 70 yards. He could see sandbags now.

The edge of the imp placement, a German helmet visible for a split second as someone moved inside. But the bunker’s design had a flaw nobody in the 116th had noticed from 400 yd out. The firing slit gave excellent visibility across the beach, but there was dead ground directly in front of the position. a small area maybe 15 ft wide where the angle of the gun couldn’t depress low enough to fire.

The Vermacht had probably planned to cover that zone with rifle fire from adjacent positions, but those positions were busy engaging other sectors. Gallagher crawled into that dead ground. He was now 25 yards from the machine gun. Close enough to hear boots scraping on concrete. Close enough to smell German tobacco. He pulled himself forward another 5 ft, then another five. The bunker entrance was on the left side, a gap in the sandbags where ammunition runners could enter. Right now, it was unguarded.

Everyone inside was focused on killing Americans in the open. 20 yards, 15 yards. This was insane. He was one private with a pistol. They were four men with a machine gun, rifles, grenades. If he missed, if he hesitated for even a second, they’d kill him before he got off three shots. But men were dying.

Every minute that gun stayed operational, more of sea company died, and nobody else was in position to do what he was about to do. 10 yards. Gallagher rose to a crouch. His legs screamed from the crawl. Sand fell from his uniform. He gripped the 45 in both hands, exactly like Uncle Sheamus taught him. Not extended like a target shooter, held close to the body. Point shooting.

Instinctive. Eight yards. Seven yards. The machine gun fired another burst. The sound was deafening this close. Hot brass ejected from the weapon. Smoke rolled out of the firing slit. Gallagher moved to the entrance. 6 yards. 5 yards. He could see inside now. Four Germans.

The gunner was seated behind the MG-42, his back partially toward the entrance. The assistant gunner was feeding a belt, focused entirely on the weapon. An NCO, probably a feld wibble, stood to the right, scanning the beach through binoculars. A fourth soldier, young, maybe 18, was stacking ammunition boxes against the wall. None of them had noticed Gallagher. Not yet.

He took three more steps four yards from the entrance. Close enough that missing was almost impossible. But close enough that if he failed, they’d kill him and be back on the gun in seconds, killing more Americans. This was it. No cover, no backup, no second chance. Gallagher rushed the entrance. The Feldwebble saw him first.

The German NCO turned, eyes widening, mouth opening to shout. His hand went to the Luger on his hip. Gallagher shot him in the chest. The 45 round hit like a sledgehammer. The felled Webble dropped backward into the bunker wall. The assistant gunner spun around, still holding the ammunition belt. Gallagher fired twice. center mass. Both rounds connected. The German fell across the machine gun.

The young soldier by the ammunition boxes was screaming, fumbling for his rifle. Gallagher put two rounds into him. The kid collapsed onto the boxes. The gunner was still seated, trapped behind the weapon, trying to swing around. He was grabbing for a pistol too slow.

Gallagher fired his last two rounds from 6 ft away. The gunner slumped over the MG42. Seven shots, 11 seconds, four dead Germans. The machine gun silent. Gallagher’s ears rang. Cordite smoke filled the bunker. His hands were shaking so badly he nearly dropped the pistol. He stood there breathing hard, staring at what he’d just done. Then training kicked in.

He pulled the assistant gunner off the MG42, checked the weapon. Still loaded, still operational. He grabbed the bipod and wrenched it sideways, bending the mount so the gun couldn’t traverse smoothly. Then he kicked over the ammunition boxes and grabbed every belt he could carry. Outside the bunker, the beach was still chaos. But without the machine gun, men were starting to move.

Gallagher saw soldiers from Baker Company advancing on his left. Third platoon was getting organized. Medics were working on wounded. He stumbled out of the bunker, still holding his empty 45 and three belts of German ammunition. His legs almost gave out. The adrenaline was crashing, leaving him hollow and shaking.

Sergeant Frank Donnelly from Second Platoon saw him first. Donnelly was a coal miner from Pennsylvania, built like a truck, and he’d watched Gallagher’s entire crawl from behind a beach obstacle. He ran over, grabbed Gallagher by the shoulders. What the hell did you just do? Gallagher couldn’t answer. His voice wouldn’t work. He just held up the empty pistol.

Donnelly looked at the bunker, at the silent gun, at the German ammunition in Gallagher’s other hand. Holy Mary, mother of God, you crawled up there. You crawled right up to it. Captain Reynolds, the acting company commander now that Lieutenant Brennan was dead, appeared from somewhere.

He was bleeding from a scalp wound, but still moving. He looked at Gallagher at the bunker, back at Gallagher. Private, what’s your name? Gallagher. Sir, Vincent Gallagher. Reynolds stared at him. You just assaulted a fortified position alone with a pistol. Yes, sir. That’s not doctrine. That’s not procedure. That’s not anything we teach. No, sir.

Reynolds looked back at the bunker, at the bodies on the beach, at the men from sea company who were still alive because one private had decided training manuals didn’t matter as much as keeping his friends from dying. You’re either the bravest man I’ve ever seen or the craziest. Don’t know, sir. Just couldn’t watch anyone else get killed. Reynolds nodded slowly.

How many Germans in there? Four, sir. All dead. Weapon secure. Disabled the mount, sir. Grabbed their ammunition. Reynolds put a hand on Gallagher’s shoulder. Good work, son. We’ll talk about this later. Right now, get your ass behind cover before someone else shoots you. Gallagher nodded and stumbled toward the seaw wall where the rest of sea company was regrouping.

Men stared at him as he passed. Word was already spreading. Somebody took out the machine gun, that private, the short guy from Brooklyn. He crawled right up to it. Gallagher sat down hard against the seaw wall. His hands were still shaking. The adrenaline was completely gone now, replaced by a bone deep exhaustion that made his whole body feel like lead.

He reloaded his 45 pistol with a fresh magazine, more out of habit than necessity. Private first class Bobby Fletcher, a farm kid from Iowa, sat down next to him. Fletcher had been pinned down 30 yards back during the whole assault. He’d seen everything. “That was the craziest thing I ever saw,” Fletcher said. “You just crawled straight at them.

” seemed like the only option. Nobody crawls at machine guns. You know that, right? Nobody does that. Somebody had to. Fletcher was quiet for a moment. Then how’d you know it would work? Gallagher thought about Red Hook, about Doc fights, about Uncle Sheamus and close quarters gunfights. Didn’t know, but I knew standing up wasn’t working. figured staying low, getting close.

Maybe that was different enough. Different? Yeah. Fletcher laughed, a slightly hysterical sound. That’s one word for it. The beach was still a nightmare. Wounded men everywhere, bodies in the surf, artillery falling further in land, but dog green sector was starting to move again. Without that MG42, the Vermach’s defensive line had a gap. Engineers were clearing obstacles.

More troops were landing. The invasion was grinding forward. Gallagher closed his eyes. He could still see the Feld Wable’s face. The young kid by the ammunition boxes couldn’t have been more than 18. The gunner trying to turn around knowing he was about to die. “You okay?” Fletcher asked. “No, but I’ll deal with it later.” “Fair enough.

” They sat there for several minutes, letting the chaos of D-Day wash over them. Other men from sea company filtered over, some wounded, some just exhausted. They all looked at Gallagher differently now, like he’d done something impossible, like he’d changed something fundamental about what was possible in combat.

Captain Reynolds came back 40 minutes later. By then, Gallagher had caught his breath and stopped shaking. Reynolds crouched next to him. Gallagher, I need to ask you something. And I need you to be completely honest. Yes, sir. That crawl, that approach, that close quarters assault, did we teach you that? Gallagher thought about lying. Thought about saying, “Yes, sir. It was all army training.

” But Reynolds deserved the truth. “No, sir. Learned it before I enlisted. Different kind of fighting. Reynolds nodded. Thought so. Because what you did violates about six different sections of the infantry manual. Assaulting prepared positions requires squad level coordination. You’re supposed to use grenades covering fire. Multiple angles of attack.

You just crawled straight at them with a pistol. Yes, sir. I should write you up for reckless endangerment, for disobeying tactical doctrine, for risking your life and your weapon in an unauthorized assault. Gallagher waited, but you saved about 30 lives in the next 10 minutes alone.

Without that gunfiring, we got organized, moved forward, secured the sector. So instead of writing you up, I’m going to recommend you for a bronze star. Reynolds paused. But more importantly, I’m going to write a report about this technique, about what you did. Because if it worked here, it might work other places. I’m not in trouble, sir.

Son, you just won this sector of Omaha Beach. If I tried to discipline you, the men would lynch me. Reynolds stood up. Get some rest. We move in land in two hours. Gallagher spent those two hours trying not to think about the four men he’d killed, about how close he’d come to dying, about the fact that pure desperation and Brooklyn street fighting had somehow become battlefield innovation.

But word was spreading faster than he realized. Fletcher told his squad. his squad told second platoon. By the time sea company moved inland toward Verville, every soldier in the 116th had heard about the private who crawled to a machine gun nest and killed the crew with a pistol. Most of them thought it was a fluke, a desperate act by a desperate man in desperate circumstances. Nobody thought it was repeatable.

They were wrong. 3 days later, the 116th was fighting through the hedge south of Eini. The French countryside was a nightmare of narrow lanes, high earn banks, and thick vegetation, perfect for defense. The Vermacht was using it brilliantly, setting up machine gun positions in every hedge corner, every sunken road, every farmhouse.

Sea company was pinned down again. A German machine gun, this time an MG34, had them trapped in a field. Three men were already wounded trying to flank it. The position was too well protected for grenades, too concealed for effective rifle fire. Private Fletcher, who’d watched Gallagher on Omaha Beach, was lying in the mud next to Sergeant Donnelly.

The machine gun fired another burst, tearing through the hedge above their heads. Fletcher looked at Donnelly. What Gallagher did on the beach? You think that was just luck? Donnelly, who’d led infantry assaults for 18 months, thought about it. Don’t know why. Because I’m looking at this position and I’m thinking maybe his way makes more sense than ours. Donnelly studied the hedge row.

The machine gun was maybe 40 yards forward behind a thick earthn bank. Every time someone moved, they got shot at, but nobody was watching the approach low along the ditch line. You want to crawl up there? With my pistol? Yeah, that’s insane. So was Omaha Beach. Donnelly was quiet for a long moment. Then he keyed his radio.

Captain Reynolds, this is Donnelly. I’ve got a man who wants to try Gallagher’s technique on that machine gun. Reynolds’s voice crackled back. Explain. Fletcher wants to crawl to it. Low approach. Use his sidearm at close range. Long pause. Is Gallagher with you? No, sir. He’s with third platoon. Fletcher volunteering for this.

Fletcher nodded. Donnelly replied. Yes, sir. Another pause. Then tell him to be careful and tell him if it works. He’s buying Gallagher a beer. Fletcher grinned. He checked his 45, made sure he had a full magazine. Then he started crawling along the ditch line exactly like Gallagher had done on Omaha Beach.

Low, slow, patient, using the terrain. It took him 11 minutes to cover 40 yard. The Germans never saw him. He got within 12 ft of the position, rose up, and killed both machine gunners with four shots. The Vermached squad in the hedge row, surrendered 2 minutes later. When sea company moved forward, Reynolds called both Fletcher and Gallagher to his position.

He looked at them for a long moment. That’s twice now. Two different men. two successful close assaults on machine gun positions using pistols. He pulled out a notebook. I want both of you to write down exactly what you did step by step. How you approached, how you moved, what you were thinking, everything. Gallagher and Fletcher exchanged glances.

They spent that evening writing reports that would eventually reach the 29th Infantry Division headquarters. reports that described a technique nobody had officially taught, but that was proving brutally effective in close quarters combat. By June 15th, every company in the 116th had heard about it. By June 20th, soldiers in the entire 29th division were discussing the Gallagher crawl.

By July, men in other units were trying it, not always with pistols. Some used submachine guns, some used grenades, but the core technique was the same. Stay low. Move slow. Get close before the enemy notices. Strike at point blank range where accuracy doesn’t matter. And surprise is everything. The German forces in Normandy started noticing something was wrong.

Verm mocked afteraction reports from July 1944 mentioned American soldiers infiltrating to extremely close range and assaulting prepared positions from unexpected angles. One report from a company commander in the 382nd Infantry Division noted, “The Americans have abandoned their previous doctrine of fire and maneuver in favor of individual stalking attacks.

Machine gun crews are being killed before they can respond.” By August, as the 29th Division pushed through the St. low breakout. The technique was spreading through word of mouth across the entire invasion force. Soldiers from other divisions who fought alongside the 29th picked it up. Replacements arriving from England heard about it in training.

It wasn’t in any manual. Wasn’t official doctrine. Just battlefield adaptation spreading through an army that was learning to fight differently. September 1944, the 29th division was pushing into the Sief Freed line. Captain Reynolds, now a major, was called to division headquarters. He brought Gallagher with him.

The meeting room had three colonels, two majors, and a brigadier general. They’d read Reynolds’s report. They’d read the afteraction reports from June through September. They’d counted the results. Brigadier General Norman Kota looked at Gallagher. Private, I understand you initiated what we’re now calling close approach assault tactics. Yes, sir.

On Omaha Beach. Were you taught this technique in training? No, sir. learned it before I enlisted. Brooklyn street fighting according to your report. Yes, sir. Cota nodded. Your technique and variations of it have been used successfully in 47 documented instances since D-Day.

Casualties among machine gun assault teams have dropped by approximately 34% when using close approach tactics versus standard fire and maneuver. Conservative estimates credit these tactics with saving between 70 and 90 American lives in the past 3 months. Gallagher didn’t know what to say. He’d just been trying to survive, trying to save his friends.

He hadn’t been thinking about doctrine or innovation or anything beyond the next 10 minutes. Cota continued, “We have a problem, private. What you did violates existing army regulations on infantry assault tactics. It’s not in the field manual. It hasn’t been tested by the infantry school. It hasn’t been approved by higher command.

He paused. But it works. And men who use it live longer than men who don’t. One of the colonels spoke up. We’re considering court marshal charges, reckless endangerment, disobeying tactical doctrine, unauthorized modification of approved assault procedures. Gallagher felt his stomach drop. Bronze Star recommendation or not, the army could still destroy him for doing what he’d done. Then Cota held up a hand.

However, General Bradley has reviewed the reports. He’s authorized a field modification to existing doctrine pending formal review. As of today, close approach assault tactics are officially recognized as an acceptable alternative to standard fire and maneuver when conditions warrant. He looked at Gallagher. No court marshal, no charges. Instead, you’re being transferred to division training section.

You’re going to teach this technique to replacement companies before they hit the line. Sir, I’m not a trainer. I’m a rifleman. You’re a rifleman who invented a tactic that’s saving lives. That makes you a trainer. Cota stood. This war is full of soldiers following doctrine and dying. We need more soldiers thinking like you did on Omaha Beach, seeing what’s not working and trying something different.

Gallagher was transferred to the division training section in October 1944. He spent the next 7 months teaching replacement soldiers how to assault fortified positions using close approach tactics. How to move low, how to use terrain, how to get close enough that a pistol became more effective than a rifle.

Most of the replacements thought he was crazy at first. Then they’d see the casualty statistics. They’d talk to veterans who’d used the technique. They’d realize that sometimes battlefield survival meant ignoring the manual and trusting instinct. The war ended in May 1945. Gallagher was rotated home in June.

He’d never been wounded, never been captured, never received his Bronze Star because paperwork got lost somewhere between France and division headquarters. He didn’t care about the medal. He cared that men he’d trained had survived. He returned to Brooklyn in July 1945. Back to Red Hook, back to the docks. He got his old job back, hooking cargo on the Atlantic Basin Pierce. He married a girl named Mary O’Sullivan in 1946.

They had three kids. He never talked about the war much. The army, however, didn’t forget. In 1947, the infantry school at Fort Benning published a revised field manual that included close approach assault tactics as an approved method for attacking fortified positions in restricted terrain.

The technique was officially designated individual infiltration assault in the manual. No mention of Omaha Beach. No mention of Gallagher. Just dry technical language describing movement patterns, approach angles, and engagement ranges. Veterans knew the truth. The technique spread through postwar armies. The British adopted it for urban combat training. The Canadians integrated it into their infantry doctrine.

By the 1950s, special forces units were teaching advanced versions that incorporated night movement and suppressed weapons. Gallagher worked the docks for 32 years. He retired in 1977 with a pension and a bad back from decades of heavy lifting. He spent his retirement fixing cars in his garage, going to mass every Sunday, and avoiding conversations about D-Day.

When people asked about his service, he’d say he was in the infantry, landed at Normandy, did his job like everyone else. He died in his sleep on November 3rd, 1989 at the age of 68, heart attack, quick and painless. His obituary in the Brooklyn Daily mentioned his long shoreman career, his family, and one paragraph about his World War II service with the 29th Infantry Division. No mention of Omaha Beach.

No mention of the machine gun nest. No mention of the doctrine he’d changed. His funeral was small. Family, dock workers, a few elderly men from the neighborhood. But three veterans showed up who weren’t from Brooklyn. One had flown from Pennsylvania. One drove from Virginia. The third came from North Carolina. They’d all served in the 29th Division.

They’d all been taught Gallagher’s technique. They stood at the graveside and didn’t say much, but they’d come because they knew. After the funeral, one of them, former Sergeant Frank Donnelly, the coal miner from Pennsylvania, talked to Gallagher’s son, Michael, told him what his father had done on June 6th, 1944.

Told him about the crawl, the assault, the four Germans, the silent machine gun. Told him about the 47 successful uses of the technique, the 70 to 90 lives saved, the doctrine change. Michael listened to the whole story. Then he asked, “Why didn’t he ever talk about it?” Donnelly thought for a moment. “Because your father never saw himself as a hero. He saw himself as a dock worker who did what needed doing.

” In his mind, crawling to that machine gun wasn’t brave. It was just the only option that made sense. Standing up got people killed, so he stayed low. That’s how he looked at life. Find what works. Do it. Don’t make a big deal about it. The technique Gallagher improvised on Omaha Beach is still taught today, though modified and refined through 80 years of military evolution.

Modern infantry doctrine calls it stealth approach under suppression or individual direct assault. Special operations forces teach advanced versions for hostage rescue and counterterrorism, but the core principle remains. Sometimes the best way to defeat a fortified position isn’t to stand off and trade fire. Sometimes you get low, get close, and kill the enemy before they realize you’re there.

The US Army Infantry School maintains a file on the development of close approach assault tactics. It includes Captain Reynolds’s original report from June 1944, combat afteraction reports from the Normandy campaign, statistical analysis from Fort Benning researchers, and a brief biographical note on Private Vincent Gallagher. The file notes that Gallagher’s technique reduced casualties among assault teams by an estimated 30 to 40%.

And has been credited with saving hundreds of lives across multiple conflicts. But that’s just statistics and reports. The real legacy is simpler. It’s in every infantry soldier who’s been taught to move low under fire. every special operations trooper who’s learned to close with an enemy position before engaging every tactical manual that acknowledges sometimes you have to break doctrine to save lives.

That’s how military innovation actually happens. Not through committees at the Pentagon, not through years of research and development, through desperate men in desperate situations who decide to try something different because the approved method is getting their friends killed. Through dock workers and coal miners and farm kids who bring their civilian skills to combat and figure out what actually works.

Vincent Gallagher never saw himself as an innovator. He was just a kid from Red Hook who knew how to fight close and decided that knowledge might be useful on a French beach. He didn’t set out to change army doctrine. He just wanted to stop watching men die.

But in the 18 minutes it took him to crawl 70 yards and kill four Germans with seven pistol shots, he proved that sometimes the best tactical innovation comes from ignoring what you’ve been taught and trusting what you’ve learned. That morning on Omaha Beach, while officers were shouting about fire and maneuver and coordinated assaults, Gallagher remembered street fights in Brooklyn.

Remembered Uncle Sheamus saying, “Get close, point, and pull the trigger. Remembered that in his world, the rules were simple. Stay low, move quiet, hit first.” and 42 dead Americans in dog green sector turned into a breakthrough because one private decided doctrine wasn’t as important as survival. If you found this story compelling, please like this video and subscribe to stay connected with these untold histories. Leave a comment telling us where you’re watching from.

News

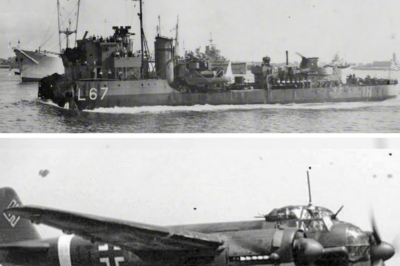

CH2 90 Minutes That Ended the Luftwaffe – German Ace vs 800 P-51 Mustangs Over Berlin – March 1944

90 Minutes That Ended the Luftwaffe – German Ace vs 800 P-51 Mustangs Over Berlin – March 1944 March…

CH2 The “Soup Can Trap” That Destroyed a Japanese Battalion in 5 Days

The “Soup Can Trap” That Destroyed a Japanese Battalion in 5 Days Most people have no idea that one…

CH2 German Command Laughed at this Greek Destroyer — Then Their Convoys Got Annihilated

German Command Laughed at this Greek Destroyer — Then Their Convoys Got Annihilated You do not send obsolete…

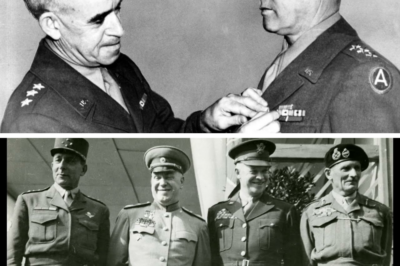

CH2 Why Bradley Refused To Enter Patton’s Field Tent — The Respect Insult

Why Bradley Refused To Enter Patton’s Field Tent — The Respect Insult The autumn rain hammered against the canvas…

CH2 Germans Couldn’t Stop This Tiny Destroyer — Until He Smashed Into a Cruiser 10 Times His Size

Germans Couldn’t Stop This Tiny Destroyer — Until He Smashed Into a Cruiser 10 Times His Size At…

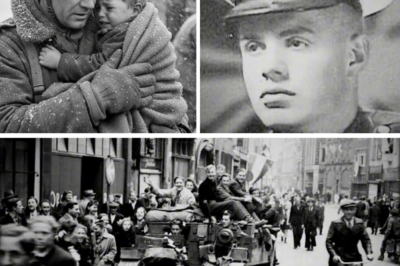

CH2 When a Canadian Crew Heard Crying in the Snow – And Saved 18 German Children From Freezing to Death

When a Canadian Crew Heard Crying in the Snow – And Saved 18 German Children From Freezing to Death …

End of content

No more pages to load