They Mocked His P-51 “Knight’s Charge” Dive — Until He Broke Through 8 FW-190s Alone

The winter sky over Germany in December 1944 was a sharp, merciless blue, the kind that seemed to cut through the soul before it touched the skin. At 28,000 feet, the air was thin, bitter, and metallic. Captain Raymond Lich’s breath came in shallow, measured pulls, each exhale frosting the edges of his leather flight mask. The Mustang beneath him shivered and groaned, a slender silver spear hurtling through a void that would swallow anything not precise, not calculated. Below, the B-17 bombers they were escorting bled smoke from flak holes, their crews hunched behind shattered plexiglass, eyes wide with fear. Every bomber mattered. Every life mattered. And Lich, suspended between clouds and the cold embrace of gravity, had a plan that no one else dared consider.

The eight Focke-Wulf 190s were climbing, precision incarnate, circling like predators waiting for the careless, the tired, the hesitant. Each German pilot had learned the Mustang’s weaknesses—the hesitation at steep angles, the instinctive pull-up at terminal velocity—and they were exploiting it. Lich’s wingmen hovered above, hovering too long in disbelief, watching him roll inverted with a sharp click of the stick, the dive angle screaming impossibility. Over the radio, startled voices called him mad. He didn’t respond. Words would be useless; the geometry alone would speak.

Before the war, Lich had been a high school mathematics teacher in Pennsylvania. Triangles, vectors, the abstract elegance of proofs—that had been his world. He had not dreamed of wings or machine guns. He had dreamed of answers, of clarity. And now, suspended in the lethal ballet of sky and steel, those same principles guided him. Every motion of the Mustang, every calculation of speed and descent, was an equation he had rehearsed in solitude over English countryside flight strips and winter clouds. The dive he had chosen was precise—dangerous, yes, but not accidental. He understood the physics; he had calculated every variable.

The altitude dropped swiftly beneath him. The Mustang’s skin shivered at 400 miles per hour, the sound of rushing air filling the cockpit, a roaring tide pressing against every panel and instrument. Each second was measured, every fraction accounted for, as he carved a path straight into the formation of eight FW190s. The German pilots barely registered the approaching silver blur before they were forced to scatter. One rolled hard left, another banked desperately, but Lich’s dive was a vector too fast, too steep, too precise. He had become a meteor, a projectile of calculated fury.

As the first cannon rounds tore into one FW190, smoke curling in sudden spirals, the others scrambled. Confusion replaced confidence in the enemy formation. Lich’s body endured pressures most pilots were never trained for, muscles screaming, vision narrowing, the stick vibrating against his palms. And yet, the mathematics held. The Mustang stayed structurally sound, the nose aligned, the guns ready. By the time he pulled up, cleared the immediate chaos, and leveled his wings, the Germans were disorganized, fleeing, broken in formation but not yet broken in spirit. The bombers below—hearts in their throats moments before—remained intact.

He climbed again, scanning the sky, calculating the next vector. The Knight’s Charge, though not yet named, had proven its terrifying validity. His wingman caught up, voice trembling through the radio, disbelief hanging in every word. “What just happened?” he asked. Lich only adjusted the throttle and pointed upward, the answer contained in numbers, angles, and the silent poetry of motion. The lesson was cruel, elegant, and immutable: the sky was a battlefield of vectors, not impulses, and courage without calculation was folly.

Lich knew the next step. Doctrine would never permit this maneuver. Officers would call it reckless. Rules would call it madness. But the mathematics, precise, unyielding, was clear: hesitation was death; calculation was survival. And so, over the frostbitten clouds of December Germany, he began refining a tactic that would change the escort of bombers forever, a maneuver born of logic, courage, and a refusal to accept fear as strategy.

Continue below

The first time Lich executed the dive, it was December 5th, 1944. The morning sun glinted off frost-laden clouds as the 357th Fighter Group climbed over Murzberg. The Mustangs above the bomber formation were like guardians suspended in silver, engines humming with measured intensity, wings trembling in anticipation of the unknown. Below, the B-17s flew in battered formations, flak-riddled and weary, each man inside the steel birds hoping the escorts would hold. And above them, eight FW190s began their climb, textbook precision, disciplined, unflinching.

Lich’s Mustang rolled inverted, nose pointed toward the earth in a dive so steep it seemed the aircraft itself defied reason. The other pilots shouted over the radio, their voices sharp with panic, calling him insane, calling him mad, calling him dead before he even fired a round. None of it mattered. The calculus of speed, mass, and angle had been done a hundred times in the quiet of flight strips and over endless English clouds. The Mustang was more than a machine in Lich’s hands—it was a vector of inevitability.

The air grew colder the lower he fell, biting at exposed skin under the leather of his flight suit, frosting his oxygen mask edges, chilling him to the bone. Speed built impossibly fast; 400 miles per hour, then 420, the altimeter unwinding like a clock in reverse. He had memorized every second of the descent, every moment that would determine success or catastrophe. The FW190s were still climbing, their focus on the bombers below, unseeing, unprepared. In that instant, the world narrowed to a single line of calculation: the center of the enemy formation, the moment to fire, the trajectory that would break their cohesion.

Then, the guns spoke. Cannon fire erupted from the Mustang’s wings, tearing into the nearest FW190. Smoke erupted in black spirals, pieces of fuselage scattered, and the German pilot was forced to bail, parachute blossoming against the cold winter sky. The other seven scrambled, rolling and diving, trying to escape the impossible vector barreling toward them. Lich’s dive was relentless. He passed through the formation like a silver knife, the Mustang vibrating under immense stress, the nose lifting only at the precise calculated moment, and then climbing back into altitude. The German formation was shattered, scattered, and the B-17s continued without further attack.

Back at the rendezvous point, Lich’s wingman finally closed in, his voice raw with disbelief. “I—I don’t understand. How did you—?” Lich only glanced over, adjusting throttle and checking instruments. “Geometry,” he said. The word was small, almost a whisper, but it carried the weight of years of study, practice, and silent obsession. It wasn’t luck, it wasn’t recklessness—it was precise calculation, applied with courage.

Word spread quickly through the squadron. Captain Lich was called into the commander’s office, a storm of anger and incredulity greeting him. “This is not protocol! You could have died! Or worse, lost the aircraft!” The commander’s voice rose, but Lich stood calm, unwavering. “Sir,” he said, “I calculated the forces, the angle, the pull-out. I know what the Mustang can take. I know what I can endure. It’s not recklessness. It’s geometry. The enemy cannot react fast enough to intercept if the dive is precise. The effect is total. They scatter. The bombers survive.”

The commander stared, exasperated, his mind refusing to reconcile the math with the madness he had just witnessed. “Can you teach it?” he finally asked, voice low, the anger mixing with a hint of awe. “Yes,” Lich replied. “If they understand the calculation, the timing, and the pull-out, they can survive. They can succeed.”

Two days later, Lich stood in front of thirty skeptical pilots, a chalkboard before him, diagrams drawn in white chalk. He explained vectors, energy states, terminal velocity, G-forces, and control surface loading. Half of the pilots doubted his sanity. The other half were too tired to argue, eyes glazing over with exhaustion. But then, he played the gun camera footage. Thirty men watched, frozen in silence, as a lone Mustang dove into eight enemy fighters and emerged intact.

That silence transformed into fascination. Three pilots volunteered immediately to attempt the maneuver under supervision. Over the next week, Lich led them into the skies over the English Channel, climbing to 25,000 feet, teaching, guiding, correcting. One pulled out too early, skidding across the clouds like a falling leaf. Another nearly blacked out from G-forces, staggering back into formation. But the third, a young lieutenant from Ohio, executed it flawlessly, landing with hands still trembling from the intensity of controlled terror. “It’s like riding lightning,” he said. Lich corrected him. “It’s understanding lightning.”

By December 24th, 1944—Christmas Eve—the Knight’s Charge had become the only weapon standing between battered bomber formations and total annihilation. Six Mustangs rolled inverted in unison, diving straight into sixteen FW190s in a chaotic sky over the Ardennes. Guns spat fire, engines screamed, and within moments, three enemy fighters were destroyed, two collided, and the rest scattered in fear. The bombers survived. Not a single Mustang was lost. The Knight’s Charge was no longer theory. It was doctrine in action.

The effect was more than tactical. Bomber crews began requesting the 357th by name. The once-distant escorts were now living shields, aggressive and unyielding. Loss rates fell dramatically: from four percent per mission in January 1945 to 1.7 percent by March for formations under groups trained in the Knight’s Charge. Allied intelligence intercepted messages from the Luftwaffe, ordering pilots to avoid the diving Mustangs entirely. Fear itself had become part of the weapon. And Lich, teacher-turned-legend, remained quiet, letting mathematics and action speak for him.

As the war approached its final desperate weeks, the skies over Germany were a crucible. The Luftwaffe, fuel-starved and diminished, fought with reckless ferocity. Me262 jets appeared sporadically, lightning-fast, impossible to intercept in force. Lich flew his eighty-third sortie on April 10th, 1945, over a railyard outside Berlin. Smoke and fire trailed from bombed targets, flak erupted in deadly clouds, and scattered FW190s and Bf109s tried to pick off stragglers. But the Knight’s Charge had become instinctive, a shield and sword combined. Four Mustangs dove simultaneously, vertical arcs slicing into the enemy formation, leaving two fighters destroyed, the rest fleeing, and the bombers intact once more.

By the end of the war, Lich’s maneuver, born from curiosity, calculation, and courage, had saved countless lives. The Knight’s Charge, though unauthorized in its inception, was now a permanent part of fighter tactics, taught in schools and analyzed in intelligence reports. It was not luck. It was not bravado. It was mathematics in motion, a proof that understanding and daring could bend even the most rigid rules of engagement.

Winter 1944 had hardened the soldiers on the ground, but the skies above the Ardennes became a crucible all their own. December 26th, the day after Christmas, dawned gray and biting cold. Snow clung to the treetops, and the landscape beneath the clouds was a mix of frozen rivers, bombed-out villages, and tracks carved by tanks and artillery. Intelligence had reported German movements, but the enemy was unpredictable, fluid, like water squeezing through cracks. And somewhere in that frozen maze, bomber formations carried ordnance meant to cripple supply lines, unaware of the chaos looming above.

The 357th scrambled as reports came over the radio: FW190s and Bf109s were spotted climbing from cloud cover, low visibility, their approach masked by winter’s murk. Pilots gripped their sticks, engines humming, instruments flickering in the dim light, hearts hammering with a mix of fear and anticipation. Lich climbed to 28,000 feet, scanning the horizon with a practiced eye, each cloud a potential threat, each glint of metal a promise of destruction or survival.

He knew the Knight’s Charge would be tested today not as an experiment, but as a lifeline. Six Mustangs followed him into the gray expanse, rolling inverted in formation, engines screaming, noses pointing toward the unknown. Below, the bombers trudged through the cold air, engines laboring, crews tense, hands white on controls, hoping that the Mustang shields would hold.

And then the Germans appeared. Sixteen FW190s burst from the clouds in coordinated arcs, guns flashing, engines roaring, aiming to tear apart the bomber formations below. They had no idea what was coming. Lich signaled, the formation inverted, and the Mustangs plummeted into the enemy with terrifying precision. Airspeed skyrocketed. Altitude bled away beneath them. The sky was a storm of engines, smoke, tracer rounds, and the distant echoes of anti-aircraft fire.

The Knight’s Charge struck like a hammer on steel. The first three FW190s were ripped apart before they could react, cannon fire shredding wings, fuselages, and pilots forced to bail out into the cold emptiness. Confusion spread like wildfire among the remaining aircraft. Two collided in panic, spiraling toward frozen fields below. The rest scattered, diving chaotically, unable to anticipate the vector of the Mustang dive. Lich’s flight climbed back to altitude, engines screaming, hearts pounding, and then dove again in perfect unison, repeating the assault.

By the time they returned to the rendezvous, six enemy aircraft were destroyed, two more likely written off, and the bomber formations had suffered minimal losses—a miracle under any measure of winter air warfare. Bomber crews cheered over the radio, voices trembling with relief and disbelief. “They’re angels,” one crewman said. “They’re not pilots—they’re gods in silver Mustangs.” Lich said nothing, checking instruments, adjusting throttle, and repeating the mantra that had carried him through countless dives: geometry, calculation, logic.

The Knight’s Charge spread beyond the 357th. Word of the maneuver reached other groups, some dismissing it as reckless, others trying and failing, losing aircraft and men in a sky that demanded absolute precision. But in the hands of those who understood, who studied Lich’s vectors, timing, and energy states, it became a tool that reshaped the air war. Missions that had once promised disaster now ended with pilots and bombers returning intact, a testament to discipline paired with daring, calculation paired with courage.

February 1945 brought a new set of challenges. The Luftwaffe was collapsing, desperate, yet still capable of localized terror. Fuel shortages and shattered production lines left German pilots using every ounce of experience to make each sortie count. FW190s were joined by remaining Bf109s and occasional Me262 jets, unpredictable and lightning-fast. The skies were a chaotic dance, a collision of human will and machine, of strategy and instinct.

Lich flew his eighty-first mission during this period, a strike near the Ruhr Valley. Visibility was poor, clouds slicing the sunlight into dim, scattered shafts. Below, the target—a rail junction vital for German logistics—was crowded with freight and troop movements. Anti-aircraft fire erupted in thick clouds, black puffs spiking the sky. German fighters appeared in small groups, diving from clouds, attempting slashing attacks on the bombers.

Lich led his flight into the first dive. Each Mustang rolled inverted, engines screaming, diving almost vertically toward their targets. FW190s and Bf109s attempted to maneuver, but the sheer closure rate and unpredictability of the dives threw them into panic. Tracer fire tore through the sky, engines roared under strain, wings flexed to near breaking points, and yet Lich’s calculations held. Aircraft pulled out of dives at the precise moment, climbing back into altitude, maintaining energy, and striking again. By the end of the sortie, four enemy aircraft were destroyed, the bombers had suffered minimal losses, and morale among Allied airmen soared.

The Knight’s Charge was no longer just a tactic—it was a psychological weapon. German pilots learned to fear the sky above as much as the storm below. Reports filtered back: “Avoid formation if the Mustangs are high,” some said. “If you see the dive forming, break away.” The maneuver had reshaped the enemy’s approach, forcing them into defensive, fragmented strategies, reducing their effectiveness, and ensuring bomber survival.

Even as the war neared its conclusion in April 1945, the skies over Germany were still perilous. Fuel, aircraft, and pilot shortages left the Luftwaffe vulnerable, yet their desperation made them deadly. Each sortie could be the last. Each engagement a gamble with death hanging in icy clouds. But the Knight’s Charge had proven itself time and again—a blend of courage, calculation, and unshakable discipline.

For Lich, the war was no longer about personal survival, or even glory. It was about saving men, about proving that logic, when applied with courage, could bend reality. And as he led his flight into yet another dive over Berlin, cutting through enemy formations, scattering German fighters, and ensuring that bombers completed their missions, the principle he had discovered—the unstoppable force of geometry applied in combat—became undeniable.

The sky was no longer just air and clouds. It was angles, vectors, momentum, fear, and will. And Lich, teacher and pilot, mathematician and warrior, was its master.

Spring 1945 brought both the collapse of Nazi Germany and the final, desperate fury of the Luftwaffe. Allied forces pressed from the west, Soviet forces from the east, and the skies over Germany had become a dangerous arena for those still willing to fight. Fuel was scarce, aircraft were patchworked and worn, and pilots—both American and German—had been tested to their limits. Each mission was a gamble with death, yet in this chaos, the Knight’s Charge remained a stabilizing force, a lifeline for bomber crews who had learned to look for silver Mustangs slicing through the clouds like bolts of controlled lightning.

Lich flew what would become his eighty-third and final combat mission on April 10th, 1945. The target: a heavily defended railyard outside Berlin, a hub of remaining supply and retreat. Clouds hung low, obscuring terrain and enemy positions. Anti-aircraft fire erupted in thick, black puffs, each burst a reminder that danger was omnipresent. Bomber formations staggered, engines laboring, crews tense and pale with fatigue.

Then, German fighters appeared. FW190s and Bf109s, disorganized yet aggressive, streaked from the clouds, attempting to attack scattered bombers. Lich and his flight climbed above, rolling inverted in formation before diving at near-vertical angles, the Knight’s Charge executed with deadly precision. The Germans had seen it before, but the speed and geometry of the dive still left them unprepared. Aircraft were torn apart before they could react. Engines smoked, wings broke, and the panic spread across the formation.

By the end of the mission, two enemy fighters were destroyed, the rest scattered into the horizon, and the bombers completed their run with minimal damage. Lich’s flight returned to base, engines smoking, bodies exhausted, yet alive. The Knight’s Charge had once again proven that logic, speed, and precise calculation could turn a desperate gamble into survival.

As the war ended in May 1945, the skies over Germany quieted, but the impact of Lich’s work endured. Bomber losses had dropped, pilot morale soared, and Allied air superiority was cemented not merely through firepower, but through the understanding that mathematics and courage could be as lethal as any weapon. Post-war, the maneuver was studied, filmed, dissected, and eventually codified into doctrine, influencing generations of fighter pilots who would never know the quiet genius of the man who first dared to plummet toward eight enemy aircraft alone and survive.

Raymond Lich returned to Pennsylvania in August 1945, awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross, though he did not attend the ceremony. The war was behind him, but the principles he had proven lived on—in manuals, training films, and the hearts of pilots who understood that mastery of the sky required more than instinct or bravery. It required understanding, logic, and the courage to act against convention.

He returned to teaching mathematics at his old high school, quietly resuming a life of chalkboards and triangles. He never spoke of his combat missions to students, never recounted the dives that had saved dozens of bomber crews. When asked why geometry mattered, he would smile slightly and say, “Because the world is made of angles. And the ones who understand them shape what happens next.”

Raymond Lich died in 1983. His obituary was brief: teacher, veteran, survived by two daughters. There was no mention of the Knight’s Charge, no recounting of the December dive that broke eight enemy fighters and changed doctrine. Yet in the archives of the Air Force Historical Research Agency, his name appeared in seventeen tactical studies. His gun camera footage remained in use, showing students of the sky that courage, logic, and precise calculation could bend the rules of combat.

In the end, Lich’s legacy was not in medals, speeches, or fanfare. It was in the angles, the math, and the quiet truth he proved in the skies above Europe: the most dangerous weapon in the air is not the plane itself, but the mind that commands it. He had taken the sky as it was, seen what others missed, and in doing so, ensured that dozens of men saw home again. The Knight’s Charge lived on, a testament to intellect, daring, and the unyielding precision of one extraordinary pilot.

News

CH2 How a US Soldier’s ‘Coal Miner Trick’ Killed 42 Germans in 48 Hours

How a US Soldier’s ‘Coal Miner Trick’ Singlehandedly Held Off Two German Battalions for 48 Hours, Ki11ing Dozens… January…

CH2 How One Engineer’s “Stupid” Twin-Propeller Design Turned the Spitfire Into a 470 MPH Monster

How One Engineer’s “Stupid” Twin-Propeller Design Turned the Spitfire Into a 470 MPH Monster The autumn rain hammered down…

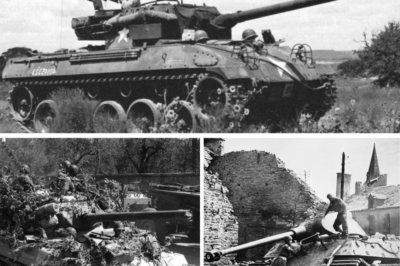

CH2 German Tank Commander Watches in Horror as a SINGLE American M18 Hellcat Shatters Tiger ‘So-Called’ Invincibility from Over 2,000 Yards Away

German Tank Commander Watches in Horror as a SINGLE American M18 Hellcat Shatters Tiger ‘So-Called’ Invincibility from Over 2,000 Yards…

CH2 How a U.S. Soldier’s ‘Metal Trick’ Killed 10.000 Germans in 6 Days and Saved 96.000 Americans

How a U.S. Soldier’s ‘Metal Trick’ Killed 10.000 Germans in 6 Days and Saved 96.000 Americans The Normandy sun…

CH2 The Man Who Defied D.E.A.T.H Itself And The Real Life Captain America – How Audie Murphy Became The Greatest Soldier Of Modern Warfare

The Texan Farm Boy Who Defied D.E.A.T.H Itself And The Real Life Captain America – How Audie Murphy Became The…

CH2 P47 Pilot Battles 20 German Fighters Over 90 Miles, Ditches in Freezing Channel to Save 9 Men from Certain De@th

P47 Pilot Battles 20 German Fighters Over 90 Miles, Ditches in Freezing Channel to Save 9 Men from Certain De@th…

End of content

No more pages to load