They Mocked His “Kitchen” Apron — Until He Killed 100 Japanese in One Day

At 14:00 hours on January 16th, 1942, Sergeant Joseé Kaluga scrubbed rice pots beside his field kitchen near Kulis Baton Province when the battery B 75mm gun position 1,000 yds north fell silent during a Japanese artillery bombardment. Kugus was 34 years old with 12 years in the Philippine Scouts, but he was a mess sergeant, not a gunner. The scouts had lost 11 artillery crews in the previous nine days.

Every gun position that went silent stayed silent. The Battle of Batan had begun 10 days earlier when American and Filipino forces completed their withdrawal to the Baton Peninsula. 80,000 troops and 26,000 civilians were now trapped on a jungle peninsula 60 mi long and 20 m wide. The Japanese 14th Army controlled everything north of Batan.

General Masaharu Homa had ordered his forces to take baton in 50 days. His artillery and aircraft had been pounding American positions since January 7th. Kugas had joined the Philippine Scouts in 1930 at age 23. He completed basic training at Fort Sil, Oklahoma, then artillery school.

The scouts assigned him to the 24th field artillery regiment at Fort Stenberg in the Philippines. He married, started a family. By 1941, he had transferred to the 88th Field Artillery Regiment as a mess sergeant. His job was feeding soldiers, not fighting them. The Philippine Scouts were the elite Filipino units of the United States Army. They had been fighting since 1901.

Professional soldiers, American officers, Filipino enlisted men. But baton was destroying them. By mid January, scout artillery batteries were operating at half strength. The Japanese had air superiority. Every gun position was mapped. Crews died faster than replacements arrived. The scouts kept firing anyway. On the morning of January 16th, Kugas had served lunch to the battery B gun crews.

Rice, canned salmon, whatever supplies remained. The scouts were already on half rations. No resupply was coming. Everyone knew it. After lunch, Kugas and his mess crew cleaned equipment near their kitchen position. The 88th field artillery guns were imp placed in the woods 1,000 yards north.

The crews had been firing all morning at a Japanese infantry column advancing toward the American defensive line. Then the Japanese artillery found them. Kugas heard the enemy shells hitting the gun position. Explosions. Then silence. No return fire. He waited. Still nothing. The Japanese column would reach the American infantry in minutes without artillery support. Kugas knew what a silenced gun meant.

Dead crew, destroyed equipment, or both. The Japanese were pushing hard. They needed to break through before American reinforcements arrived. Every gun that stopped firing made their job easier. Did Kugas’ decision save the line? Please give this video a like. It helps share these stories and subscribe. Back to Baton. Kugas grabbed 16 volunteers from his mess crew and nearby positions.

They would cross 1,000 yards of open ground to reach the gun. Rice patties, no cover. Japanese aircraft were strafing the area. Their artillery was still firing. Every man knew the odds. Most crews caught in the open died before reaching safety, but the gun had to get back in action. The Japanese column was still advancing. American infantry was waiting for artillery support that had stopped coming.

The volunteers started running. Japanese fighters spotted them immediately. Machine gun fire tore across the rice patties. Artillery shells began falling. Men went down. Some stopped, turned back. Kugas kept running. A few stayed with him. The distance closed. 900 yd, 800, 700. The Japanese artillery intensified.

They knew Americans were moving toward the gun position. More volunteers fell. Kugas ran harder. He reached the gun position alone. The other volunteers were gone, dead, wounded, or driven back. The 75 mm gun sat in a bomb crater next to its imp placement. The crew was scattered, some dead, some wounded. One gunner was still alive, and Kugas, a cook, was now the only man standing who could fire the weapon.

The Japanese column was 300 yd away and closing fast. Kugas dropped into the crater. The 75mm gun had been blown sideways by the bomb blast. The breach mechanism was intact. The barrel looked straight. The recoil system showed no visible damage, but the gun sat at the wrong angle. Useless. He needed to upright it and get it back into the imp placement. One man could not move a 1500 lb artillery piece.

He needed help. The wounded gunner was conscious, a private from the regular crew, hit in the shoulder, but mobile. Kugas found two more gunners from adjacent positions. They had seen him running across the patties. Followed him in. Four men total. Enough to move the gun if they worked fast. The Japanese artillery was still falling. Shells hit 50 yards away, 40 yard.

The enemy had observers watching this position. They knew Americans were here. Kugas had trained on these guns at Fort Sil in 1930, 12 years ago, but artillery crews drilled the same procedures until they became automatic. He knew every step. The men grabbed the gun trails, lifted. The gun moved 6 in.

They set it down, adjusted their grip, lifted again another 6 in. Japanese machine gun fire raked the position from the north. The column was closer now, 250 yd, still advancing. They got the gun upright. Kugas directed them to roll it back onto the firing platform. The private with the shoulder wound operated the trail spade while the other two gunners manhandled the carriage.

Continue below

At 14:00 hours on January 16th, 1942, Sergeant Joseé Kaluga scrubbed rice pots beside his field kitchen near Kulis Baton Province when the battery B 75mm gun position 1,000 yds north fell silent during a Japanese artillery bombardment. Kugus was 34 years old with 12 years in the Philippine Scouts, but he was a mess sergeant, not a gunner. The scouts had lost 11 artillery crews in the previous nine days.

Every gun position that went silent stayed silent. The Battle of Batan had begun 10 days earlier when American and Filipino forces completed their withdrawal to the Baton Peninsula. 80,000 troops and 26,000 civilians were now trapped on a jungle peninsula 60 mi long and 20 m wide. The Japanese 14th Army controlled everything north of Batan.

General Masaharu Homa had ordered his forces to take baton in 50 days. His artillery and aircraft had been pounding American positions since January 7th. Kugas had joined the Philippine Scouts in 1930 at age 23. He completed basic training at Fort Sil, Oklahoma, then artillery school.

The scouts assigned him to the 24th field artillery regiment at Fort Stenberg in the Philippines. He married, started a family. By 1941, he had transferred to the 88th Field Artillery Regiment as a mess sergeant. His job was feeding soldiers, not fighting them. The Philippine Scouts were the elite Filipino units of the United States Army. They had been fighting since 1901.

Professional soldiers, American officers, Filipino enlisted men. But baton was destroying them. By mid January, scout artillery batteries were operating at half strength. The Japanese had air superiority. Every gun position was mapped. Crews died faster than replacements arrived. The scouts kept firing anyway. On the morning of January 16th, Kugas had served lunch to the battery B gun crews.

Rice, canned salmon, whatever supplies remained. The scouts were already on half rations. No resupply was coming. Everyone knew it. After lunch, Kugas and his mess crew cleaned equipment near their kitchen position. The 88th field artillery guns were imp placed in the woods 1,000 yards north.

The crews had been firing all morning at a Japanese infantry column advancing toward the American defensive line. Then the Japanese artillery found them. Kugas heard the enemy shells hitting the gun position. Explosions. Then silence. No return fire. He waited. Still nothing. The Japanese column would reach the American infantry in minutes without artillery support. Kugas knew what a silenced gun meant.

Dead crew, destroyed equipment, or both. The Japanese were pushing hard. They needed to break through before American reinforcements arrived. Every gun that stopped firing made their job easier. Did Kugas’ decision save the line? Please give this video a like. It helps share these stories and subscribe. Back to Baton. Kugas grabbed 16 volunteers from his mess crew and nearby positions.

They would cross 1,000 yards of open ground to reach the gun. Rice patties, no cover. Japanese aircraft were strafing the area. Their artillery was still firing. Every man knew the odds. Most crews caught in the open died before reaching safety, but the gun had to get back in action. The Japanese column was still advancing. American infantry was waiting for artillery support that had stopped coming.

The volunteers started running. Japanese fighters spotted them immediately. Machine gun fire tore across the rice patties. Artillery shells began falling. Men went down. Some stopped, turned back. Kugas kept running. A few stayed with him. The distance closed. 900 yd, 800, 700. The Japanese artillery intensified.

They knew Americans were moving toward the gun position. More volunteers fell. Kugas ran harder. He reached the gun position alone. The other volunteers were gone, dead, wounded, or driven back. The 75 mm gun sat in a bomb crater next to its imp placement. The crew was scattered, some dead, some wounded. One gunner was still alive, and Kugas, a cook, was now the only man standing who could fire the weapon.

The Japanese column was 300 yd away and closing fast. Kugas dropped into the crater. The 75mm gun had been blown sideways by the bomb blast. The breach mechanism was intact. The barrel looked straight. The recoil system showed no visible damage, but the gun sat at the wrong angle. Useless. He needed to upright it and get it back into the imp placement. One man could not move a 1500 lb artillery piece.

He needed help. The wounded gunner was conscious, a private from the regular crew, hit in the shoulder, but mobile. Kugas found two more gunners from adjacent positions. They had seen him running across the patties. Followed him in. Four men total. Enough to move the gun if they worked fast. The Japanese artillery was still falling. Shells hit 50 yards away, 40 yard.

The enemy had observers watching this position. They knew Americans were here. Kugas had trained on these guns at Fort Sil in 1930, 12 years ago, but artillery crews drilled the same procedures until they became automatic. He knew every step. The men grabbed the gun trails, lifted. The gun moved 6 in.

They set it down, adjusted their grip, lifted again another 6 in. Japanese machine gun fire raked the position from the north. The column was closer now, 250 yd, still advancing. They got the gun upright. Kugas directed them to roll it back onto the firing platform. The private with the shoulder wound operated the trail spade while the other two gunners manhandled the carriage.

Kugas checked the elevation wheel, the traversing mechanism, both functional. He opened the breach. Clear. The ammunition stores had not been hit. Armor-piercing rounds, high explosive, everything they needed was still there. Kugas loaded an armor-piercing round. The Japanese column was crossing a wooden foot bridge over a creek 200 yd north.

Infantry, trucks, horsedrawn artillery quesons. They were bunched up at the bridge. Perfect target. He aimed. The wounded private steadied the trail. Kugas fired. The round hit the bridge dead center. Wood exploded. The lead truck tilted sideways into the creek. Japanese soldiers scattered. He loaded again. High explosive this time. Aimed at the vehicle stacked up behind the destroyed bridge. Fired.

The shell detonated among three trucks. Ammunition aboard one vehicle cooked off. Secondary explosions ripped through the column. The Japanese advance stopped. Troops dove for cover. Their officers were shouting orders Kugas could not hear, but he could see the result. The column was trapped. Bridge gone. Vehicles burning. No way forward.

Kugas kept firing. The other gunners loaded rounds and adjusted the trail as he called corrections. High explosive into the infantry concentrations, armor-piercing into the remaining vehicles. The Japanese tried to ford the creek. He dropped shells into the water. Men went down in the explosions. The column started pulling back away from the bridge, away from the creek, away from the American line they had been pushing toward. The Japanese artillery shifted fire.

Shells began landing directly on Kugus’ position. The enemy observers had pinpointed his gun. Every Japanese battery in range was now targeting the single 75mm piece that had stopped their advance. The bombardment intensified. Shells hit 30 yards out, 20 yards, 15. Kugas and his improvised crew kept firing, but the odds had just changed. The Japanese were not going to let this gun keep shooting.

They were going to destroy it. Kugas had fired 18 rounds in 12 minutes. He had stopped the Japanese column, killed dozens of soldiers, destroyed multiple vehicles, but now every enemy gun within 3 mi was aimed at his position. The next salvo was already in the air. He had seconds to decide.

Stay and die or move the gun and survive to fight again. The American infantry line was still waiting for artillery support. The Japanese would attack again as soon as this gun went silent. Kugas made the decision in 3 seconds. He would not abandon the gun, but he would not stay in the crater either. The woods were 30 yards west, dense jungle.

The Japanese observers could not see through that canopy. He could fire from the crater, then move the gun into the trees before the counter fire arrived. Shoot and hide again and again. The Japanese would waste shells on empty positions while he kept hitting their column. He and the three gunners manhandled the gun out of the crater, rolled it across open ground to the treeine.

Japanese shells landed where they had been standing 10 seconds earlier. Dirt and shrapnel flew. The men dove into the jungle, waited. The bombardment continued for 2 minutes, 40 rounds at least, all hitting the abandoned crater. When the firing stopped, Kubas moved the gun back to the crater’s edge. Loaded, aimed at the Japanese column, regrouping north of the destroyed bridge. He fired three rounds, high explosive.

The shells landed among the troops trying to reorganize. Then he and the crew hauled the gun back into the woods. 20 seconds later, Japanese artillery saturated the crater again. The enemy was firing blind now. They knew the general area, but could not pinpoint the gun. Kugas had turned their own artillery doctrine against them.

Observers called corrections. Batteries fired. But by the time the shells landed, the American gun was gone. For the next 6 hours, Kugas repeated the pattern. Move gun to firing position. Fire three to five rounds. Move gun back into jungle. Wait for Japanese counter battery fire. Move gun to new position. Fire again.

The Japanese artillery crews grew frustrated. They fired hundreds of rounds trying to silence one American gun. They hit nothing but empty ground in trees. Meanwhile, Kugas kept destroying their vehicles and killing their troops. By 1600 hours, Kugas had fired 47 rounds. The Japanese column had completely halted its advance. Dead and wounded littered the area north of the creek.

Burning vehicles blocked the road. The enemy infantry had dug in. They were not moving forward anymore. The American defensive line held. Other 88th Field Artillery batteries had withdrawn to new positions during the fighting, but this one gun operated by a mess sergeant and three volunteers had given them time to displace without Japanese pressure. The ammunition supply was running low.

Kugas counted the remaining rounds. 13 armor-piercing, eight high explosive, 21 total, enough for maybe four more fire missions. The sun was setting. The Japanese artillery had slowed. Their observers could not see in the fading light. This would be his last chance to inflict damage before darkness stopped the fighting. He positioned the gun at the crater edge one more time.

Kugas aimed at the Japanese positions north of the creek. They had established a command post near a large tree. He could see officers moving around it. Radio antennas, map tables. He loaded armor-piercing, fired. The round went high, exploded in the tree canopy. He adjusted elevation, fired again, direct hit. The command post disappeared in the explosion. Japanese soldiers scattered.

Their communications were disrupted. Their coordination broken. He fired the remaining 19 rounds over 30 minutes. methodical, precise, each shell placed exactly where it would cause maximum disruption. When the last round was gone, Kuga surveyed the battlefield. The Japanese advance had been stopped. The American line held. The 88th Field artillery had successfully withdrawn.

His mission was complete, but he still had two problems. The gun needed to be evacuated before the Japanese attacked at dawn, and his field kitchen was still sitting 1,000 yd south with all his equipment. Kugas found two trucks from a retreating supply column.

The drivers had been ordered to abandon anything that could not move fast. He explained the situation, showed them the gun, told them about the kitchen. The drivers agreed to help. They would take the gun first, then the kitchen. Both had to be evacuated before sunrise or the Japanese would capture them. Kugas and the three gunners loaded the 75mm onto the first truck.

But moving the gun had created a new problem. The Japanese now knew it was being evacuated. Their artillery opened fire again. And this time the trucks were visible targets. The first truck carrying the 75mm gun pulled away from the treeine at 18:30 hours. Japanese artillery shells began landing immediately.

The enemy had maintained observation on the area despite the darkness. They knew something was moving. The driver accelerated. Kugas and the three gunners rode on the truck bed, steadying the gun as the vehicle bounced over the rough road. Shells hit 50 yards behind them, then 40 yard. The Japanese were walking their fire along the road. The truck reached the 88th Field Artillery’s new position 3 mi south at 1900 hours. The gun was intact.

The crew was alive. Kugas reported to the battery commander, explained what had happened. The commander listened, said nothing. Sent Kugas back north for the kitchen equipment. The second truck was waiting where they had left it. The Japanese were still shelling the area, but less intensely now. Darkness had reduced their accuracy.

Kugas and two volunteers loaded the field kitchen onto the truck. pots, pans, rice bags, canned goods, everything that could be salvaged. The mess sergeant’s job did not stop because he had spent the afternoon firing artillery. Men still needed to eat. The truck made the return trip without incident. The Japanese had shifted their artillery to other targets.

By 2100 hours, Kugas was back with battery B. He set up the kitchen, cooked beans and rice, served the meal to the gun crews who had been fighting all day. Then he cleaned the equipment and prepared for the next morning. The battery commander filed the report that night, sent it up the chain of command.

By January 18th, the report had reached General Douglas MacArthur’s headquarters on Corrior Island. MacArthur read it personally. A mess sergeant had run 1,000 yards under fire without orders, operated a gun alone for 6 hours, stopped a Japanese advance, evacuated the weapon, and returned to cooking duties. MacArthur had seen many acts of courage in 40 years of military service. This one stood out.

He recommended Kugas for the Medal of Honor. The paperwork moved fast by military standards. The War Department approved the recommendation on February 24th, 1942. General Order number 10 announced the award. Sergeant Joseé Kugus would receive the Medal of Honor for his actions on January 16th.

He was the first Filipino American to earn the medal in World War II. But there was a problem. Kugus could not receive the medal yet. The fighting on Baton was getting worse, much worse. By late January, the American and Filipino forces were running out of everything. Food, medicine, ammunition. The halfrations became quarter rations, then 1/8 rations.

Disease spread through the units. Malaria, dysentery, dingay fever. Men could barely walk, but they kept fighting. The Japanese had been reinforced. Fresh divisions, new artillery, more aircraft. General Homa was under pressure from Tokyo. Baton should have fallen by midFebruary. It was now late February, and the Americans still held the peninsula. Kugas continued serving as mess sergeant for battery B.

He cooked whatever food remained, rice, occasionally fish, sometimes just broth made from grass and bark. The gun crews needed calories to operate the weapons, but the food supply was nearly gone. The scouts were eating their horses, their pack mules, anything to stay alive. The Japanese knew the Americans were starving. They just had to wait. Time was on their side.

In early March, President Franklin Roosevelt ordered MacArthur to evacuate to Australia. The general did not want to leave, but orders were orders. He departed Corodor on March 11th. Left General Jonathan Waywright in command of all forces in the Philippines. Waywright knew the truth. No reinforcements were coming. No resupply, no rescue.

The Philippines had been written off. They would fight until they could not fight anymore. then they would surrender. It was only a question of when. By early April, the Japanese launched their final offensive. Fresh troops, heavy artillery, constant air attacks. The American and Filipino lines began collapsing. Units retreated, reformed, retreated again.

The scouts fought harder than anyone, but they were starving, sick, exhausted. On April 8th, Major General Edward King, commander of forces on Baton, made the decision. He would surrender. Approximately 76,000 American and Filipino troops would become prisoners of war.

It was the largest surrender in American military history, and Joseé Kuga’s, Medal of Honor recipient, was about to become a prisoner of the Japanese Army. The surrender came at noon on April 9th, 1942. General King sent officers under a white flag to meet Japanese commanders. The terms were simple. Unconditional surrender. All troops would lay down their weapons immediately.

All equipment would be turned over intact. The Japanese would provide food and medical care for prisoners. That last promise was a lie. What followed was one of the worst atrocities in modern warfare. Kugus was with Battery B when the order came. The scouts were told to destroy their guns before surrendering.

The men used sledgehammers on the breach mechanisms, poured sand into the barrels, made the weapons useless. Then they waited for the Japanese to arrive. Kugus had one problem the other soldiers did not have. He was a Medal of Honor recipient. The Japanese high command knew about the medal. They monitored American communications.

If they discovered Kugas had earned the award, they would execute him immediately or subject him to special torture. He needed to hide any evidence. The general order announcing his Medal of Honor was a piece of paper in his field pack. Kugus found a shovel, dug a hole, buried the order deep in the ground near a tree he hoped to remember.

Then he told every scout in Battery B to forget about the metal, never mention it. If the Japanese asked questions, he was just a cook, nothing more. The men agreed. They understood what would happen if the secret came out. The march began on April 10th. The Japanese called it a transfer to prisoner of war camps.

The Americans and Filipinos would walk from Baton to Camp Oddonnell near Capus, Tarlac Province, 65 mi. The Japanese said it would take 4 days. They provided no food, no water, no medical supplies. Men who could not walk would be left behind. That was the official policy. The reality was worse. Men who fell were beaten, shot, beheaded.

The Japanese soldiers treated prisoners like animals, sometimes worse than animals. Kuba started walking with 76,000 other prisoners. Filipinos and Americans mixed together. The first day was bearable. Men were weak from months of starvation, but most could still move. The second day was harder. The tropical heat was brutal. No shade, no water. Men began collapsing.

The Japanese guards bayonetted anyone who stopped. left the bodies on the road. Other prisoners had to step over the corpses and keep walking. Anyone who tried to help the fallen was beaten or killed. On the third day, Kugas contracted malaria, fever, chills, delirium. Many men with malaria died during the march. The disease combined with dehydration and starvation was lethal.

But Kugas realized the fever gave him an advantage. The Japanese guards avoided sick prisoners. They did not want to catch diseases. If Kugas looked sick enough, they might leave him alone. He exaggerated the symptoms, shook harder than necessary, wrapped himself in burlap sacks he found along the road, trembled visibly whenever guards inspected the column. The strategy worked.

Guards saw him shaking, assumed he was dying, moved on to harass other prisoners. Kugas kept walking. The malaria was real. The performance made it look worse. He stayed in the middle of the column. Never at the front where strong prisoners were. Never at the back where weak prisoners were executed. Middle was safest, anonymous, invisible.

Just another sick Filipino soldier in a river of 76,000 dying men. By the fourth day, the death toll was catastrophic. Bodies lined the road every few hundred yards. The tropical sun accelerated decomposition. The smell was overwhelming. Men who had survived four months of combat on Baton were dying on a road march.

No enemy fire, no heroic last stands, just heat, disease, and Japanese brutality. Kuga saw friends from battery B collapse. He could not help them. Helping meant dying. He kept walking. The prisoners reached San Fernando Pampanga on the fifth day. The Japanese loaded them into metal freight cars. 100 men per car designed for 30. No ventilation, no water.

The heat inside the cars was 120° or higher. Men died standing up, their bodies held upright by the press of other prisoners. The train ride to Kapas took 4 hours. When the doors opened, dozens of corpses fell out of each car. The survivors stumbled onto the platform. Then they walked the final 8 miles to Camp O’Donnell.

Kugas was still alive, but the real test was just beginning. Camp O’Donnell was a death camp in everything but name. The Japanese had built it to hold 10,000 prisoners. By midappril 1942, it held 50,000. No sanitation, one water spigot for the entire camp. Prisoners stood in line for 12 hours to fill a canteen. Dysentery killed hundreds every day.

The bodies were stacked outside the barracks until burial details could drag them to mass graves. Men who had survived the death march died within weeks at O’Donnell. Kugas arrived at the camp on April 14th. The guards searched prisoners at the gate. Took anything valuable. Watches, rings, money. They beat prisoners randomly. No reason, just because they could.

Kuga still had his malaria. The real symptoms mixed with his exaggerated performance kept the guards away. They shoved him toward the barracks, told him to find a space. He walked into a building designed for 200 men. 800 prisoners were crammed inside. No beds, no blankets, just wooden floors and the smell of death. The Japanese provided almost no food.

Rice once a day, maybe a handful per prisoner, sometimes nothing. Men were dying at a rate of 30 to 50 per day. The guards did not care. They considered prisoners subhuman, unworthy of decent treatment. The Geneva Convention meant nothing here. Camp O’Donnell operated by one rule. The strong might survive.

The weak would definitely die. Kugus was determined to be in the first category. He noticed patterns. Guards beat prisoners who made eye contact. Prisoners who walked too slowly. Prisoners who walk too fast. The safe zone was middle speed, eyes down, no distinctive behavior, invisible. He applied the same strategy from the death march.

Blend in, look sick, but not dying. Avoid attention. When burial details were called, he volunteered. The work was horrific, but it kept him moving. Movement meant circulation. Circulation fought disease better than lying still in the barracks. The months crawled by. May, June, July, August. The death rate at Camp O’Donnell was so high the Japanese transferred some prisoners to other camps. Kugas stayed.

His malaria came and went. Each time the fever spiked, he exaggerated it. Guards continued avoiding him. By September, he had survived 5 months. Many of the men who arrived with him were dead. The survivors were skeletal, malnourished, diseased, but alive.

The Americans and Filipinos had formed networks, shared food, shared information, shared hope that liberation might come. In January 1943, a Filipino official from Pampanga province petitioned for Kugaz’s release. The Japanese sometimes released Filipino prisoners for agricultural work. They needed laborers for farms and mills. The official claimed Kugaz was needed for rice production. The petition was approved.

On January 15th, 1943, exactly 1 year and 1 day after his Medal of Honor action, Kugas walked out of Camp O’Donnell. He had survived 9 months in hell, lost 40 lbs, suffered repeated beatings, watched thousands die, but he was alive and free. Sort of. The Japanese assigned him to a rice mill in Pampanga. The work was hard. 12-hour days, minimal food, but it was better than the camp.

No random beatings, no mass death. Kugas operated milling equipment, processed rice for Japanese supply convoys. The overseers watched constantly. Any sign of sabotage meant execution, but they could not watch everything, and they definitely could not watch thoughts. Kugas began planning his next move. Filipino guerilla units were operating throughout Luzon. Resistance fighters who had escaped the surrender.

Former soldiers who melted into the jungle. Civilians who refused Japanese occupation. They raided supply convoys. Ambushed patrols. Gathered intelligence for MacArthur’s headquarters in Australia. The gorillas needed men with military experience. Kugas had 12 years in the Philippine scouts, artillery training, combat experience. He was exactly what they needed.

But first, he had to make contact without the Japanese discovering his plan. A resistance member approached him in March 1943. Quiet conversation near the mill. The gorillas knew about Kugas, knew about his Medal of Honor, wanted him to join, but leaving immediately would be suspicious.

The Japanese would hunt down escapees, execute anyone who helped them. Kugas needed to be patient. Gather information first, spy on Japanese operations at the mill, pass intelligence to the resistance, prove his value, then escape when the time was right. He agreed. By April, Sergeant Joseé Kugas, Medal of Honor recipient and prisoner of war survivor, had become a spy for the Philippine resistance.

The Japanese had no idea the cook they had captured was about to become one of their most dangerous enemies. Kuga spent 6 months as a spy at the rice mill. He memorized Japanese patrol schedules, counted supply trucks that arrived each week, noted which roads were guarded and which were not.

The information passed to resistance contacts who visited the mill disguised as farmers selling vegetables. The gorillas used the intelligence to plan ambushes. They knew when convoys would be lightly guarded, when patrols would be away from their bases, when the Japanese were vulnerable.

Kugas never saw the results of his information, but Japanese casualties in Pampanga province increased through the summer of 1943. By October, the resistance decided Kugas was more valuable in the jungle than at the mill. They had enough spies. They needed experienced soldiers. A guerilla unit called Squadron 227 Old Bronco was operating in Noeva Province under Major Robert Lapam and Captain Harry McKenzie. Both were American officers who had escaped the baton surrender.

They commanded roughly 300 Filipino fighters, former soldiers, farmers, students, anyone willing to fight the Japanese occupation. The squadron needed an artillery specialist. Kugas fit perfectly. The escape was planned for October 23rd. Kugas would leave the mill during his lunch break, walk into the jungle, and never return. The resistance had prepared a route through areas without Japanese patrols.

Local farmers would provide shelter and food along the way. By October 25th, he had reached the old Bronco headquarters deep in the mountains of NEWEA. Major Lapam interviewed him personally, verified his identity, confirmed his Medal of Honor citation, then promoted him to second lieutenant, and gave him command of a weapons platoon.

Kugus was back in the war. But this war was different from Baton. No front lines, no artillery support, no supply chain. Guerilla warfare meant hit-and-run attacks, ambushes, sabotage. The Japanese controlled the cities and major roads. The guerillas controlled everything else. They moved at night, struck fast, disappeared before Japanese reinforcements arrived.

The tactics were effective, but dangerous. Captured gerillas were tortured and executed. Civilians suspected of helping guerillas were massacred. The stakes were higher than conventional combat. The weapons platoon under Kugas specialized in raids on Japanese supply depots. They would scout a target for weeks, learn the guard patterns, identify weak points, then attack at the most vulnerable moment, steal weapons, ammunition, and food, destroy what they could not carry, vanish into the jungle before the garrison could respond. By early 1944, Kugas had led 17 successful

raids. Zero casualties among his men. The Japanese put a price on his head. They did not know he was the Medal of Honor recipient from Baton. They just knew a guerilla officer was causing serious problems in Noea. In June 1944, Allied forces invaded Normandy and Europe. The war was turning against Japan on all fronts.

MacArthur was pushing north through New Guinea toward the Philippines. The gorillas intensified operations to prepare for his return. Squadron 227 Old Bronco received orders to attack the Japanese garrison at Kurangalan. The target was a fortified position with 200 enemy troops, machine gun nests, mortar pits, barbed wire. Taking it would require coordination between multiple guerilla units. Kugas would lead the assault element.

The attack came on August 7th, 1944. Three guerilla companies, 450 men total, surrounded the garrison at 0300 hours. Kugus’ weapons platoon hit the main gate with concentrated rifle fire and grenades. The Japanese responded with machine guns and mortars. The firefight lasted 4 hours. Guerillas used captured Japanese weapons. Ammunition was limited. Every shot had to count.

By 0700 hours, the garrison commander surrendered. The guerillas had taken Korangalan with 23 casualties. The Japanese lost 117 killed and 83 captured. The victory was significant but temporary. Japanese reinforcements would retake Karangalan within days. The guerillas could not hold fixed positions.

They looted the garrison, took all weapons and supplies, released Filipino prisoners the Japanese had been holding, then burned the buildings, and withdrew into the mountains. The pattern repeated throughout Luzon. Attack, win, withdraw. The gorillas were preparing the islands for MacArthur’s return. And in January 1945, he finally came back. American forces landed on Luzon on January 9th, 1945.

The liberation had begun. Squadron 227 Old Bronco intensified attacks to support the American advance. Kugas led raids on Japanese communication lines, destroyed bridges, ambushed retreating enemy units. The fighting was fierce, but the outcome was inevitable. The Japanese were being pushed back. By April, most of Luzon was under American control.

The Philippine scouts who had survived the war stepped forward, rejoined the United States Army. Kugas was among them. And finally, after 3 years, he would receive the medal he had earned on January 16th, 1942. The Medal of Honor ceremony took place on April 30th, 1945 at Camp Olivas in Pampanga Province.

Major General Richard Marshall, chief of staff to General MacArthur, conducted the presentation. Kuga stood in formation with other Philippine scouts who had survived the war. He wore a new uniform, the first clean uniform he had worn in 3 years. The citation was read aloud. The action nearer Kulis Baton Province on January 16th, 1942, running 1,000 yards under fire without orders.

Organizing volunteers, operating the gun for 6 hours, stopping the Japanese advance, General Marshall placed the Medal of Honor around Kugas’s neck. The ribbon felt strange after everything he had been through. The baton death march, nine months at Camp O’Donnell, spying at the rice mill, two years fighting with the gorillas.

The medal represented one day, one action. But that action had saved the defensive line, given other units time to withdraw, held the Japanese advance for six critical hours. The medal was earned, no question. But Kugus knew the truth. Thousands of Filipino and American soldiers had fought just as bravely. Most were dead. Many had no medals, no recognition, just unmarked graves scattered across Baton and Luzon. After the ceremony, the army offered Kuga’s United States citizenship. He accepted immediately.

Then they offered him a commission as a second lieutenant in the regular United States Army. He accepted that, too. His service with the Philippine Scouts was over. The scouts would be disbanded after the war ended, but Kugas would continue serving. He was assigned to the 44th Infantry Regiment for occupation duty in Okinawa.

The war in the Pacific officially ended on September 2nd, 1945 when Japan signed the surrender documents aboard USS Missouri. Kugas remained in the army after the war. He served in Okinawa, then the Ryuku Islands, Fort Sil, Oklahoma, back to the Philippines for the 10th anniversary of the Battle of Baton in 1952.

Fort Lewis, Washington in 1953 with the Second Infantry Division. He slowly brought his family from the Philippines to the United States. His wife, four children, all became American citizens. Kugas earned his high school equivalency diploma at age 47. retired from the army in 1957 with the rank of captain after 27 years of service. Civilian life was an adjustment.

Kugas enrolled at the University of Puet Sound in Tacoma, Washington. Studied business administration, graduated in 1962 at age 55. His son later said earning that degree was his father’s most cherished achievement. After graduation, Kugas worked for Boeing Company until 1972. Then he farmed a small plot of land outside Tacoma, grew vegetables, raised chickens, lived quietly.

The Medal of Honor recipient, who had killed dozens of Japanese soldiers, and survived the worst atrocities of the Pacific War, spent his final decades in peace. Kugas organized the Baton Corodor Survivors Association, worked for 15 years helping other veterans connect, share stories, process trauma. Many survivors never talked about what they experienced. The death march was too painful. Camp O’Donnell too horrific.

But the association gave them a place to speak if they wanted or just be around others who understood. Kugas attended reunions, gave occasional interviews, but he never sought attention. His son remembered him saying the Medal of Honor belonged to all the men who died in the Philippines. He was just the one wearing it. Joseé Kabalfine Kugas died on January 18th, 1998 in Tacoma, Washington.

He was 90 years old, survived by his wife and four children, buried at Mountain View Memorial Park. His Medal of Honor is displayed at the Fort Sill Museum in Oklahoma. A relief sculpture commemorating his action stands on Mount Samat in the Philippines at the National Memorial to the Battle of Batan. The sculpture shows kugas running across open ground toward the gun position.

The moment a cook became a one-man army. The Japanese mocked soldiers wearing kitchen aprons thought cooks were not real fighters. On January 16th, 1942, Sergeant Jose Kugas proved them catastrophically wrong. One man, one gun, 1,000 yards under fire. He stopped an entire enemy column, saved the defensive line, earned the Medal of Honor, survived the death march, fought as a guerilla, lived to see liberation, then spent 50 years as an American citizen and veteran advocate. His story deserves to be remembered. If this story

moved you the way it moved us, do me a favor, hit that like button. Every single like tells YouTube to show this story to more people. Hit subscribe and turn on notifications. We are rescuing forgotten stories from dusty archives every single day. Stories about cooks who became one-man armies.

Stories about Filipino scouts who held the line when everything collapsed. Stories about men who survived death marches and came back to fight as guerillas. Real people, real heroism. Drop a comment right now and tell us where you are watching from. Are you watching from the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, Australia? Our community stretches across the entire world. You are not just a viewer.

You are part of keeping these memories alive. Tell us your location. Tell us if someone in your family served in World War II. Tell us if you have ever heard of Joseé Kugas before today. Just let us know you are here. Thank you for watching. And thank you for making sure Joseé Kugas and the Philippine scouts do not disappear into silence.

These men deserve to be remembered and you are helping make that happen.

News

CH2 THE FARMER’S TRAP THAT SHOCKED THE THIRD REICH: How One ‘Stupid Idea’ Annihilated Two Panzers in Eleven Seconds and Changed Anti-Tank Warfare

THE FARMER’S TRAP THAT SHOCKED THE THIRD REICH: How One ‘Stupid Idea’ Annihilated Two Panzers in Eleven Seconds and Changed…

CH2 THE SIX AGAINST EIGHT HUNDRED: The Guadalcanal Miracle That Even Japan Called ‘Witchcraft’ — How a Handful of Black Marines Turned a Jungle Death Trap into the Most Mysterious Stand of the Pacific War

THE SIX AGAINST EIGHT HUNDRED: The Guadalcanal Miracle That Even Japan Called ‘Witchcraft’ — How a Handful of Black Marines…

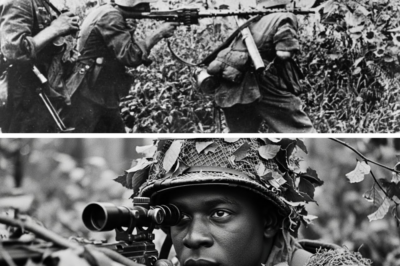

CH2 THE INVISIBLE GHOST OF NORMANDY: How One Black Sharpshooter’s Ancient Camouflage Turned Him Into the Wehrmacht’s Worst Nightmare – Germans Never Imagined One Black Sniper’s Camouflage Method Would K.i.l.l 500 of Their Soldiers

THE INVISIBLE GHOST OF NORMANDY: How One Black Sharpshooter’s Ancient Camouflage Turned Him Into the Wehrmacht’s Worst Nightmare – Germans…

CH2 THE PLANE THEY CALLED USELESS — The ‘Flying Coffin’ That HUMILIATED Japan’s Zero and TURNED the Pacific War UPSIDE DOWN

The Forgotten Fighter That Outclassed the Zero — The Slow Plane That Won the Pacific” January 1942. The Pacific…

CH2 ‘JUST A PIECE OF WIRE’ — The ILLEGAL Field Hack That Turned America’s P-38 LIGHTNING Into the Zero’s WORST NIGHTMARE and Changed the Pacific War Forever

‘JUST A PIECE OF WIRE’ — The ILLEGAL Field Hack That Turned America’s P-38 LIGHTNING Into the Zero’s WORST NIGHTMARE…

CH2 THE ENEMY WHO LANDED BY MISTAKE: How a Wounded Japanese Zero Pilot Had To Land Onto a U.S. Aircraft Carrier

THE ENEMY WHO LANDED BY MISTAKE: How a Wounded Japanese Zero Pilot Had To Land Onto a U.S. Aircraft Carrier…

End of content

No more pages to load