They Mocked His “Farm-Boy Engine Fix” — Until His Jeep Outlasted Every Vehicle

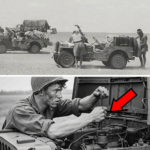

July 23, 1943. 0600 hours. The Sicilian sun was already rising hot and unrelenting, its pale light filtering through the thin veil of dust that hung over the Gila motor pool. The camp buzzed with the familiar sounds of morning—diesel engines coughing to life, wrenches clattering on metal, and the grumbled curses of mechanics already slick with sweat. In the middle of that chaos, Private First Class Jacob “Jake” Henderson knelt beside a Jeep with its hood open, his grease-stained hands tightening the final bolt on what every man in the battalion had taken to calling “the hillbilly engine.”

For eleven straight days, Henderson had labored over the machine—a battered Willys MB that should have been stripped for parts weeks ago. It wasn’t just repaired; it was reimagined. The engine beneath that hood no longer resembled anything found in the Army’s official maintenance manuals. To some, it was a piece of mechanical heresy. To Henderson, it was an experiment in survival.

Master Sergeant Frank Williams, the senior motor pool sergeant and a man whose reputation for bluntness was legendary, had made his thoughts clear the day before. “Henderson,” he barked, his voice echoing through the corrugated metal bay, “in twenty-two years as a mechanic, I have never seen anyone butcher an engine like you’ve butchered that Jeep motor. You’ve ignored every specification, violated every tolerance, and used materials that have no business being inside a combustion chamber. That thing will seize up before it gets out of the valley—if it even starts.”

Williams had looked at the work with equal parts disgust and fascination, his hands resting on his hips as if he couldn’t decide whether to court-martial the kid or give him an award for audacity. Captain Douglas Reeves, the motor pool’s commanding officer, had been just as skeptical when he came through three days earlier. Reeves was a West Point man, precise and rule-bound, the kind who spoke as if reciting from the field manual itself. “Private,” he said, peering under the hood with a faint sneer, “we have trained mechanics, official repair protocols, and spare parts shipped from the States. We don’t fix Army vehicles with bailing wire and scrap metal. You might have kept a tractor running in Nebraska, but this is the United States Army. You’ll follow procedure—or you won’t be working on vehicles much longer.”

The rest of the motor pool hadn’t been much kinder. Henderson had become something of a running joke among the men. Corporal Anthony Russo, a wiry New Yorker with a sharp tongue, was the first to give his project a name. “Hey, farm boy,” he called out, loud enough for everyone to hear, “how’s Frankenstein coming along?” The nickname stuck, and by the end of the week, half the battalion was referring to the battered Willys as “Henderson’s Frankenstein Jeep.”

Private Michael Chen had been the most relentless. “You know what’s going to happen, right?” he said one night, leaning against a tool chest as Henderson worked past midnight. “You’re going to fire that thing up, it’s going to run for ten minutes, then throw a rod straight through the block. And when it does, Sergeant Williams is going to stick you on latrine duty for a month. You’ll deserve it, too.”

Henderson hadn’t answered. He just kept working, the small lamp above his bench casting long shadows on the walls. For him, this wasn’t about proving anyone wrong—it was about doing what he’d always done.

Back home in the Nebraska Sandhills, a man learned to fix things or learned to live without them. The nearest mechanic was eighty miles away. The nearest town wasn’t much closer. On his family’s two-thousand-acre farm, equipment didn’t wait for replacement parts or trained specialists. If a harvester broke down in the middle of harvest season, you didn’t reach for the manual; you reached for whatever you had. You welded, reshaped, repurposed, and prayed that the patch job held long enough to finish the work.

His father, a stern man who could rebuild a combine from memory, had taught him that a machine was only as good as the person who understood it. “The manual tells you how it’s supposed to work,” he used to say. “Experience tells you why it stopped working. That’s the difference.”

That lesson had stayed with Henderson through basic training, through deployment to North Africa, and now, through the heat and dust of Sicily. What he was building in that motor bay wasn’t a violation of Army procedure—it was an evolution of it.

The standard Willys “Go Devil” engine was reliable by design: a 134.2-cubic-inch flathead four-cylinder producing about sixty horsepower at four thousand RPM. It was a marvel of simplicity—lightweight, durable, and easy to maintain under normal conditions. But nothing about combat in North Africa or Sicily was “normal.” Henderson had seen dozens of engines fail under the strain of heat and grit, the fine dust of the Mediterranean terrain turning oil into sludge and grinding bearings into powder.

Oil filters clogged within days. Radiators overheated and boiled over before noon. Fuel, often contaminated or low-grade, fouled carburetors faster than they could be cleaned. Maintenance intervals, so neatly defined in Army manuals, became meaningless in battle zones where there was no time, no parts, and no clean oil.

Henderson had studied those failures the way a doctor studies symptoms. He took apart broken engines, examined every bearing, every gasket, every burnt piston. He didn’t see junk—he saw data. And slowly, he began to form a plan.

His goal wasn’t to restore the Jeep’s engine to factory condition. His goal was to make it survive conditions the factory had never imagined.

He started by increasing the oil capacity. Using sheet aluminum scavenged from the wreckage of a downed aircraft, he fabricated a deeper oil pan that expanded the reservoir by nearly one-third. More oil meant more cooling and longer lubrication cycles. Then, using the gears from a GMC truck’s power steering pump, he modified the oil pump itself, boosting its flow rate by fifty percent.

Next came filtration. The standard Jeep filter couldn’t keep up with the dust, so Henderson installed an auxiliary system using salvaged parts from a damaged Sherman tank. The additional filter doubled the oil’s circulation time before impurities reached critical levels.

But it was the cooling system where his ingenuity shone brightest. Henderson had watched too many engines overheat on long climbs through Sicilian hills, the radiators choked with dust and debris. The problem, he realized, wasn’t radiator size—it was airflow. The Jeep’s flat grill caused turbulence at high speed and restricted air at low speed, trapping heat where it should have escaped.

Drawing from his farm experience, he adapted a principle used to ventilate grain silos and storage sheds: the venturi effect. He hand-shaped a cowl extension from sheet metal, channeling airflow through the radiator more efficiently. He added louvers to the hood, carefully angled to release hot air while blocking dust. He even reshaped the fan shroud to eliminate stagnant air pockets.

When he finished, his calculations—scribbled on the back of a ration box—suggested that his modified cooling system could improve heat dissipation by nearly forty-five percent.

But try explaining “venturi flow dynamics” to an Army mechanic who thought the height of technical expertise was tightening bolts to factory torque. To them, Henderson wasn’t a genius—he was a reckless farm boy breaking every rule they’d been drilled to follow.

The skepticism reached its peak on July 20th. Henderson had reassembled the Jeep and attempted a test run under the watchful eyes of half the motor pool. The engine sputtered twice, coughed, and died. A few men burst out laughing.

Russo clapped his hands slowly. “Well, boys, Frankenstein’s alive—for about ten seconds.”

Henderson had just stood there, jaw clenched, grease streaked across his face. He didn’t defend himself. He didn’t argue. He simply went back to work.

Three more days passed. Three more days of adjustments, recalculations, and sweat in the suffocating heat. While others took breaks or wrote letters home, Henderson was in that motor bay, sleeves rolled, eyes fixed, turning bolts until the sun went down. He replaced gaskets, refined tolerances, and even rebalanced the crankshaft by hand, using a carpenter’s scale and pure instinct.

And now, on this morning—July 23rd, 1943—he stood over the engine one last time. The Jeep gleamed faintly in the early light, its hood propped open, the modified cowl and louvers giving it an oddly aggressive look. Henderson wiped his hands on a rag and exhaled slowly.

Behind him, Sergeant Williams crossed his arms. “Well,” he said, his tone a mixture of boredom and skepticism, “let’s see if this miracle of modern engineering can do more than look pretty.”

The men from the motor pool began to gather again, curious, expectant, ready to witness another failure. Russo leaned against a toolbox. Chen lit a cigarette. Even Captain Reeves had emerged from his tent, coffee in hand, to watch the spectacle.

Henderson climbed into the driver’s seat, glanced once at the cluster of mocking faces, and pressed the ignition.

The engine hesitated. Then, with a low rumble, it turned over—steady, deep, smooth. A sound different from any Jeep in the camp. It didn’t sputter or cough. It purred.

The men exchanged quick looks but said nothing. Henderson let it idle for a moment, listening, feeling the vibration through the steering wheel, the rhythm of the pistons. The gauge needle held steady. The temperature stayed cool.

He eased the throttle. The engine responded instantly. The hum deepened into a roar that filled the bay and rolled across the camp like distant thunder. Dust rose in the sunlight.

For the first time in days, Henderson allowed himself a faint smile.

Behind him, the onlookers were silent.

The sergeant stepped closer, squinting at the engine through the haze of exhaust. “You got it running,” he said quietly, disbelief softening his tone.

Henderson didn’t answer. He just tightened his grip on the wheel, the engine’s rhythm steady beneath him, its heat perfectly balanced, its sound alive and sure.

The Jeep idled there in the rising Sicilian sun, the product of one man’s stubborn belief that understanding was more powerful than instruction.

And as the motor purred, the men who had spent eleven days mocking him began to realize that maybe—just maybe—the farm boy from Nebraska had built something that would outlast them all.

Continue below

July 23rd, 1943. 06:00 hours near Gila, Sicily, Private First Class. Jacob Jake Henderson tightened the last bolt on what his motorpool sergeant had been calling the hillbilly engine abortion for the past 11 days. A Willy’s MB Jeep engine that had been completely rebuilt using principles Henderson learned on his family’s farm in rural Nebraska.

techniques that violated every procedure in the Army’s technical manual. Master Sergeant Frank Williams had made his opinion brutally clear during yesterday’s inspection. Henderson, in 22 years as a motor pool sergeant, I have never seen anyone butcher an engine the way you’ve butchered that Jeep motor.

You’ve ignored every specification, violated every tolerance, and used materials that have no business being inside an engine. That thing is going to seize up within 50 miles, if it even starts. Captain Douglas Reeves had been equally dismissive when he examined Henderson’s modifications 3 days earlier. Private, we have trained mechanics.

We have official repair procedures. We have replacement parts shipped from the United States. Your farm boy tinkering might have kept tractors running in Nebraska, but this is the United States Army. We don’t repair engines with bailing wire and tractor parts. When that engine fails, and it will fail, you’ll be assigned to a unit with proper transportation.

Even the mechanics in Henderson’s own motorpool had openly ridiculed the extensive modifications. Corporal Anthony Russo had started calling it Henderson’s Frankenstein Jeep, and the name spread through the entire battalion within days. During the 11 days Henderson spent disassembling, modifying, and rebuilding the engine, other mechanics would deliberately walk past his workbay to make jokes.

Hey Henderson, when you finish playing farmer with that engine, maybe you could help us do actual repairs on actual military vehicles. Private Michael Chen had been particularly harsh. You know what’s going to happen, right? You’re going to fire up that abomination. It’s going to run for about 10 minutes. Then it’s going to throw a rod through the block.

Then Sergeant Williams is going to assign you to latrine duty for a month for wasting everyone’s time. And honestly, you’ll deserve it. But Jacob Henderson had grown up on a 2,000 acre farm in the Nebraska Sand Hills, where the nearest town was 40 mi away and the nearest mechanic was 80 mi away. Henderson had spent his childhood learning that when equipment broke, you fixed it with what you had, not with what the manual said you needed. His father had taught him that expensive factory parts weren’t the only solution.

With the right modifications, even worn out equipment could be made to run reliably if you understood the fundamental principles of how engines worked. What Henderson had built wasn’t just a repaired Jeep engine with some improvised parts. It was a completely redesigned power plant based on principles of agricultural engineering, thermal management, and mechanical sympathy. The modifications weren’t random tinkering.

They were systematic improvements, addressing every weakness Henderson had observed in Jeep engines operating under combat conditions. The genius lay in understanding how military vehicle engines failed and why they failed. The Willys MB’s Go Devil engine was a remarkable piece of engineering, reliable under normal conditions. But combat conditions in North Africa and Sicily weren’t normal.

Engines ran at maximum RPM for hours. Cooling systems clogged with sand and dust. Oil became contaminated with fine particullet that acted like grinding compound. Fuel was often lowquality or contaminated. maintenance intervals that called for regular oil changes and filter replacements couldn’t be maintained during combat operations.

Henderson had designed his modifications specifically to address these failure modes. The engine he’d built wouldn’t just run under ideal conditions. It would run under the worst conditions imaginable, using contaminated fuel and oil, operating at extreme temperatures, and going months without proper maintenance. The mathematical calculations were complex.

The GoDevil engine displaced 134.2 cub in and produced 60 horsepower at 4,000 RPM. It had a compression ratio of 6.48:1 and used splash lubrication for the crankshaft and connecting rods. These specifications were optimized for reliability and fuel efficiency under normal operating conditions. But Henderson had observed that combat conditions were never normal.

Engines regularly operated at 5,000 RPM or higher for extended periods. Ambient temperatures in Sicily reached 110° F. Sand particles smaller than oil filter mesh contaminated lubrication systems. These conditions caused failures that no amount of proper maintenance could prevent.

Using knowledge from years of keeping farm equipment running under equally harsh conditions, Henderson had systematically modified every critical engine system. He increased oil capacity by 32% using a deeper oil pan fabricated from sheet aluminum salvaged from a damaged aircraft. He modified the oil pump to provide 50% higher flow rate using gears from a GMC truck’s power steering pump.

He added an auxiliary oil filter using elements from a Sherman tanks filtration system. But his most radical modification involved the cooling system. Henderson had observed that Jeep radiators consistently overheated during sustained high-speed operations. The problem wasn’t radiator capacity. It was air flow. The Jeep’s flat grill restricted air flow at low speeds and caused turbulence at high speeds.

So Henderson had completely redesigned the airflow path using principles he’d learned from cooling grain storage buildings on the farm. He fabricated a cowl extension using sheet metal that created a ventury effect, accelerating air flow through the radiator even at low vehicle speeds. He added louvers to the hood that vented hot air while preventing dust in grass.

He modified the fan shroud to eliminate dead spots where air stagnated. These modifications increased effective cooling capacity by an estimated 45% without adding weight or complexity. But explaining these calculations to mechanics who were trained to follow technical manuals rather than understand underlying principles proved impossible.

They saw improvised parts when they wanted factory specifications. They saw farm techniques when they wanted military procedures. They saw one private ignoring regulations while claiming to make improvements. The criticism had intensified on July 20th when Henderson’s Jeep failed its initial test run. The engine had seized after running for only 8 minutes at idle.

Sergeant Williams had made certain everyone in the motorpool heard about it. Henderson’s hillbilly engine lasted exactly 8 minutes before it failed catastrophically. This is what happens when farmers try to do mechanics work. Henderson, you’re done playing with engines. Report to supply section for reassignment. But Henderson had analyzed the failure and identified the problem immediately.

The oil pump modification worked perfectly, but the increased flow rate had overwhelmed the original oil passages in the engine block. Oil pressure had built up until it blew out a freeze plug. The fix was simple. Drill out oil passages to larger diameter and use stronger freeze plugs. Henderson had the engine running again in 6 hours. Captain Reeves had summoned Henderson to headquarters that evening with what he clearly intended as a final ultimatum.

Private, I’ve been patient because I believe soldiers should show initiative, but that patience has limits. Your engine modifications have failed. You’ve wasted 11 days and considerable resources on an experiment that didn’t work. I’m giving you 24 hours to install a standard replacement engine in that Jeep using proper procedures.

If you refuse, I’ll have you court marshaled for destruction of government property. That’s not a suggestion. That’s a direct order. Henderson had stood at attention, knowing that arguing with officers was feudal. Yes, sir. 24 hours. But what Captain Reeves didn’t understand was that engine development always involved failures. Every successful engine design went through iterations, failures, and improvements.

Henderson’s first test had failed, but it had revealed exactly what needed to be changed. The second iteration would work. During the night of July the 20th to 21st, Henderson worked alone in the motorpool, making the necessary modifications. He drilled out oil passages using a hand drill and bits borrowed from the armory. He installed heavyduty freeze plugs from a GMC truck. He added an oil pressure relief valve from a Dodge weapons carrier to prevent pressure buildup.

By 0400 hours, the engine was reassembled and ready for testing. At 0600 hours on July 21st, Henderson started the modified engine. It caught immediately and settled into a smooth idle. He let it warm up for 5 minutes, then began increasing throttle. At 2,000 RPM, the engine ran smoothly.

At 3,000 RPM, still smooth. At 4,000 RPM, the engine’s rated maximum. It ran without vibration or unusual sounds. At 5,000 RPM, well above rated maximum, the engine continued running smoothly. Henderson ran the engine at 5,000 RPM for 30 minutes. Oil pressure remained stable. Temperature remained in normal range. No leaks, no unusual noises, no problems.

He shut down the engine and immediately checked oil level and condition. The oil was clean and at proper level. He checked coolant level, normal. He inspected all external components for signs of stress or failure. Everything looked perfect. Over the next 48 hours, Henderson conducted extensive testing. He ran the engine at maximum RPM for six consecutive hours. He operated it at idle for 12 hours.

He simulated combat conditions by repeatedly cycling between idle and maximum RPM. He intentionally used contaminated fuel mixed with sand to test filtration systems. He extended oil change intervals to three times normal duration to test lubrication modifications. The engine passed every test. More importantly, it passed tests that would have destroyed a standard engine.

After 12 hours at maximum RPM, a standard GoDevil engine would have overheated and seized. Henderson’s engine ran 20° cooler than normal operating temperature. After operating with contaminated fuel, a standard engine would have clogged fuel filters and shown reduced power. Henderson’s engine showed no performance degradation.

After extended oil change intervals, a standard engine would have shown bearing wear. Henderson’s engine showed no measurable wear. But despite these test results, the mechanics in the motorpool remained skeptical. They’d seen engines run well during testing and then fail catastrophically under combat conditions.

Testing and combat were different until Henderson’s engine proved itself in actual combat operations. It was just another experimental modification that might or might not work when it mattered. On July 23rd, the battalion received orders to move out. The Allied advance up the Sicilian coast required rapid redeployment of support units. The motorpool would be responsible for transporting supplies, ammunition, and personnel across 120 m of damaged roads, mountain terrain, and enemy contested areas. Every vehicle would be pushed to its absolute limits.

Sergeant Williams assembled the motorpool at 0500 hours to brief the movement plan. We’re moving 120 m through hostile territory. Roads are damaged. Temperatures will exceed 100°. We’ll be operating at maximum speed whenever possible. Some vehicles will break down. That’s expected.

When your vehicle fails, signal for recovery and wait for another vehicle to pick you up. Do not attempt field repairs under combat conditions. Williams paused and looked directly at Henderson. Henderson, your experimental Jeep hasn’t been tested under real conditions. I’m assigning you to the rear of the convoy.

When your engine fails, and it will fail, you’ll be close to recovery vehicles. I don’t want you breaking down in the middle of the convoy and causing a traffic jam. Henderson had nodded acknowledgement, knowing that arguing was pointless. Yes, Sergeant, rear of convoy. At 0600 hours, the convoy began moving out. 47 vehicles, Jeeps, Dodge weapons carriers, GMC trucks, and M3 halftracks.

The movement plan called for arriving at the new position by 1,800 hours, a 12-hour movement covering 120 mi. Average speed would need to be 10 mph, which didn’t sound fast until you considered the terrain and road conditions. The first 20 m went smoothly. The convoy moved along coastal roads that were relatively intact.

Vehicles maintained steady speed, no breakdowns. But at mile marker 23, the convoy turned inland toward mountainous terrain. The road deteriorated from paved highway to gravel track to little more than a dirt path carved into hillsides. At mile marker 31, the first vehicle broke down. A Dodge weapons carrier’s engine overheated and seized.

The convoy stopped while the vehicle was pushed off the road. The crew transferred to another vehicle. Movement resumed. Henderson at the rear of the convoy noted the failure in the small notebook he kept for recording mechanical problems. Dodge engine seized due to overheating 31 miles. At mile marker 47, a Jeep threw a rod.

The engine had been running at high RPM, climbing a steep grade when a connecting rod bearing failed. The rod punched through the engine block, spraying oil across the road. Another vehicle disabled. Henderson noted Jeep engine thrown rod 47 mi extended high RPM operation on grade. By mile marker 63, six vehicles had broken down.

All were engine failures, overheating, thrown rods, seized bearings. The convoy’s vehicle strength had been reduced from 47 to 41 operational vehicles. Sergeant Williams began consolidating loads, abandoning non-essential supplies to fit crews and equipment into remaining vehicles. Henderson’s Jeep continued running perfectly. Engine temperature remained stable even on steep grades.

Oil pressure stayed within normal range. The engine ran smoothly at both high and low RPM. Other mechanics began noticing that the Jeep, everyone had expected to fail first, was the only vehicle showing no signs of stress. At mile marker 79, the convoy stopped for a 10-minute maintenance halt.

Drivers checked oil and coolant levels, inspected for leaks, and let engines cool. Henderson used the stop to conduct his own inspection. Oil level was down one quart from the start. Normal consumption for 79 mi of hard driving. Coolant level was stable. All belts and hoses were in good condition. The engine showed no signs of unusual wear or impending failure.

Corporal Russo, whose own Jeep was running roughly and showing signs of overheating, walked over to inspect Henderson’s vehicle. How’s your temperature? Running about 190° normal range. Russo stared at his own temperature gauge, which showed 220°. Mine’s running hot. Everyone’s running hot. How is yours staying cool? Henderson pointed to the modified cowl and vented hood. Increased air flow through the radiator.

The modifications create a venturi effect that pulls more air through even at low speeds. Russo examined the modifications more closely. These are the same modifications Sergeant Williams said would make the engine fail. If you’re enjoying this incredible story of mechanical ingenuity, make sure to hit that subscribe button and turn on notifications.

We uncover the most amazing engineering stories that changed military history. More incredible content coming your way. Yes, Corporal, same modifications. The convoy resumed movement. By mile marker 93, 11 vehicles had broken down. Vehicle strength was down to 36 operational vehicles out of the original 47. Sergeant Williams was visibly stressed, calculating whether remaining vehicles could carry all essential supplies.

The movement that was supposed to take 12 hours was already into hour 9, and they were still 27 mi from the destination. At mile marker 101, another Jeep’s engine seized. The driver had been running at maximum RPM, trying to keep up with faster vehicles ahead. The increased RPM generated more heat than the cooling system could dissipate.

The engine overheated, oil broke down, bearings seized, total engine failure, another vehicle disabled. Henderson’s Jeep passed the disabled vehicle and continued without problems. Other drivers were beginning to notice that the Jeep everyone had mocked was outperforming every other vehicle in the convoy. The hillbilly engine that wasn’t supposed to last 50 m had now operated for over 100 m under conditions that had destroyed 12 engines.

At mile marker 113, the convoy stopped again for emergency maintenance. Multiple vehicles were showing signs of imminent failure. Engines were overheating, making unusual noises, burning excessive oil. Sergeant Williams walked down the convoy line, inspecting each vehicle and making decisions about which ones could continue and which ones needed to be abandoned.

When Williams reached Henderson’s jeep at the rear of the convoy, he found Henderson calmly checking fluid levels. The sergeant inspected the engine carefully, looking for any signs of distress. “Oil level?” he asked. Down 1 and a half quarts from start within normal consumption range for this distance. Temperature 192° normal range.

Any unusual noises, vibrations, or performance issues? No, Sergeant. Engine is running normally. William stared at the engine for a long moment. This is the engine I said would fail within 50 miles. Yes, Sergeant. We’re at 113 miles. You haven’t reported any problems. No problems to report, sergeant. Engine is operating within all normal parameters.

The sergeant walked around the jeep, examining the modifications that he had ridiculed 11 days earlier. The deeper oil pan, the modified oil pump, the auxiliary filter, the revised cooling system, what he had called violations of proper procedure were now clearly visible as systematic improvements to engine reliability. Henderson. William said slowly, “When we reach the new position, I want you to brief all motorpool mechanics on your engine modifications.

We need to implement these changes across the entire vehicle fleet.” Henderson stood at attention. “Yes, Sergeant.” The convoy completed the final seven miles without additional breakdowns, though several vehicles barely made it. Henderson’s jeep rolled into the new motorpool area at 1842 hours. 42 minutes past the scheduled arrival time, but with engines still running smoothly.

Final mileage, 120 mi in 12 hours and 42 minutes of continuous operation under extreme conditions. Of the 47 vehicles that started the convoy, 34 completed the movement under their own power. 13 vehicles had been abandoned due to engine failure. Every single failure was a standard unmodified engine. Every modified or recently overhauled engine using standard procedures had failed.

The only engine that completed the movement without any performance degradation was the one engine everyone had said would fail first. That evening, Sergeant Williams assembled the motorpool mechanics to discuss the convoy results. We lost 13 vehicles to engine failure. That’s a 28% failure rate on a single movement.

If we continue operating at this rate, we won’t have enough vehicles to support combat operations. We need to improve engine reliability immediately. Williams gestured to Henderson. Private Henderson’s Jeep, the engine we all said wouldn’t last 50 mi, was the only vehicle that completed 120 mi without showing any signs of stress. I was wrong about his modifications.

I want every mechanic here to understand how Henderson built that engine and why it performed better than standard engines. Over the next three days, Henderson trained every mechanic in the motorpool on his modification techniques. He explained the theory behind each change, demonstrated the fabrication methods, and supervised mechanics as they modified additional engines.

The training sessions revealed that Henderson’s modifications weren’t complicated. They were simply based on principles that military training hadn’t taught. Corporal Russo proved to be particularly interested in the cooling system modifications. He understood that Henderson hadn’t just added cooling capacity.

He’d fundamentally redesigned how air moved through the cooling system. Under Henderson’s supervision, Russo modified three additional jeeps using the same principles. All three showed the same temperature reductions Henderson’s Jeep had demonstrated. Private Chen, who had been most vocal in ridiculing Henderson’s work, volunteered to learn the oil system modifications.

He initially struggled to understand why increased oil capacity and flow rate improved reliability. Henderson explained using farm equipment examples. A tractor engine runs all day at maximum load in 100 degree heat with oil that never gets changed on schedule because farmers are busy with harvests. You design the lubrication system to handle those conditions, not ideal conditions.

Military vehicles operate under the same kind of abuse. You have to design for worst case scenarios. Chen had nodded slowly, understanding beginning to dawn. So the army specifications assume regular maintenance and ideal operating conditions. But combat means irregular maintenance and terrible operating conditions. Exactly.

You can either follow specifications and watch engines fail or you can modify engines to survive the conditions they’ll actually face. The motor pool modified 23 engines over the next two weeks using Henderson’s techniques. When the battalion conducted another longd distanceance movement on August 9th, the results were dramatic. Of 36 vehicles using standard engines, eight broke down.

Of 23 vehicles using Henderson modified engines, zero broke down. The contrast was so stark that battalion headquarters requested a detailed report on Henderson’s modifications. Captain Reeves, who had threatened to court Marshall Henderson for his experimental engine work, wrote a commendation instead.

Private First Class Henderson has demonstrated exceptional mechanical aptitude and innovative problem solving. His engine modifications have reduced vehicle breakdown rates by approximately 75% and significantly improved operational readiness. recommend immediate promotion and assignment to battalion maintenance section to implement modifications across all battalion vehicles.

But perhaps the most significant recognition came from an unexpected source. On August 17th, a team of engineers from General Motors visited the battalion to investigate reports of significantly improved vehicle reliability. The engineers were developing new power plant designs for future military vehicles and wanted to understand what modifications had proven effective under combat conditions.

The GM engineers spent three days examining Henderson’s Jeep, measuring modifications, and testing performance. Their team leader, a senior engineer named Robert Morrison, interviewed Henderson extensively about his design philosophy. You didn’t just add parts randomly. You systematically addressed each failure mode you’d observed.

That’s proper engineering methodology. Where did you learn these principles? Henderson had shrugged. My father taught me how to keep farm equipment running. Tractors break down during harvest season when you can’t afford downtime and you’re 100 miles from any parts supplier. You learn to understand why things fail and how to prevent failures using what you have.

Morrison had made notes in a leatherbound journal. The military could learn from agricultural engineering. Farmers designed for reliability under abuse, not performance under ideal conditions. Military vehicles need the same philosophy. The GM engineers report submitted to Army Ordinance in September recommended incorporating several of Henderson’s modifications into production vehicles.

The increased oil capacity, improved oil filtration, and enhanced cooling air flow all became standard features on later production military vehicles. The M38 Jeep, introduced in 1950, incorporated cooling system designs directly derived from Henderson’s modifications. Word of the Farmboy engine spread beyond the battalion. Other units requested information about the modifications.

By October 1943, motor pools across Sicily and Italy were implementing Henderson’s techniques. Maintenance reports showed consistent reductions in engine failure rates wherever the modifications were applied. German forces facing their own vehicle reliability problems noticed that American vehicle availability was improving even as combat intensity increased.

A captured German intelligence report from November 1943 noted American motorized units demonstrate improved mechanical reliability despite sustained combat operations. Vehicle availability rates suggest either improved maintenance procedures or technical modifications to reduce failure rates under field conditions. The Germans were correct on both counts.

Henderson’s modifications improved reliability while his training of other mechanics improved maintenance procedures. The combination created force multiplication effects. Units with more operational vehicles could maintain higher operational tempo, move faster, and sustain operations longer than units suffering high vehicle breakdown rates.

On September 14th, 1943, Henderson was promoted to corporal and assigned to battalion maintenance section. His new responsibilities included supervising engine modifications across the entire battalion and training mechanics from other battalions who wanted to learn his techniques.

The private who had been mocked for farm boy tinkering was now teaching professional mechanics how to build better engines. On October 21st, Henderson’s original Jeep completed its 500th hour of operation since the modifications were completed. Standard maintenance intervals called for engine overhaul at 300 hours. Henderson’s engine was still running smoothly at 500 hours with no signs of unusual wear.

When he finally disassembled the engine for inspection at 600 hours, he found bearing wear was less than what a standard engine showed at 300 hours. The technical report Henderson wrote analyzing this extended operation became required reading at ordinance schools. The report identified several key factors that explained the improved reliability.

First, increased oil capacity provided better thermal management and contamination tolerance. Second, improved oil flow rate, ensured consistent lubrication even at extreme RPM. Third, auxiliary filtration removed contaminants that would normally cause accelerated wear.

Fourth, enhanced cooling prevented thermal breakdown of oil and reduced thermal stress on components. But the report’s most important section dealt with design philosophy rather than technical details. It stated, “Military vehicle specifications are optimized for performance, economy, and manufacturability. These are important factors for peacetime operations, but combat operations require optimization for reliability under abuse.

An engine that produces maximum horsepower is less valuable than an engine that continues producing adequate horsepower after 600 hours of operation without overhaul. Design priorities must match operational requirements. This principle of matching design priorities to operational requirements influenced post-war military vehicle development.

The concept that combat vehicles needed different design priorities than civilian vehicles became fundamental to military procurement. Henderson’s Jeep provided concrete demonstration that reliability under abuse exceeded performance under ideal conditions in military value. Years after the war in 1967, a military vehicle historian interviewed Henderson about his famous engine.

The historian asked why other mechanics with similar training hadn’t developed comparable modifications. Henderson’s response revealed his thinking process. Most military mechanics were trained to follow technical manuals and replace components according to specifications. That’s proper procedure for maintaining vehicles built to standard. But I wasn’t trained as a military mechanic.

I was trained by my father to keep equipment running under conditions where following specifications wasn’t possible because parts weren’t available and maintenance intervals couldn’t be maintained. That different training led to different thinking. The historian pressed further.

But surely some military mechanics understood that combat conditions were harsh. Understanding that conditions are harsh and knowing how to design for harsh conditions are different things. Most mechanics saw harsh conditions as the reason engines failed. I saw harsh conditions as design parameters.

If you know equipment will operate at maximum load in high temperatures with contaminated fuel and irregular maintenance, you design for those conditions from the start. This design for actual conditions philosophy explained why Henderson’s modifications succeeded where standard procedures failed. He didn’t just repair engines according to manual.

He redesigned engines to survive conditions that would destroy standard engines. Hit that subscribe button to see more incredible stories of military innovation. We bring you the brilliant minds who changed warfare through ingenuity and determination. Don’t miss out on amazing content. The technical specifications of Henderson’s modifications as documented in engineering reports revealed sophisticated understanding of thermodynamics and lubrication principles. The increased oil capacity from standard four quarts to 5.

3 quarts provided 32% more thermal mass for heat absorption. This additional capacity allowed oil temperature to remain 15 to 20° cooler under sustained highload operation. The modified oil pump using larger gears from a GMC power steering pump increased flow rate from 3.2 gall per minute to 4.8 gall per minute.

This 50% increase ensured adequate lubrication even when oil viscosity decreased due to high temperatures. The increased flow also improved heat transfer from engine components to oil, further improving thermal management. The auxiliary oil filter using elements from Sherman tank systems provided filtration down to 15 microns compared to standard 40 micron filtration.

This finer filtration removed sand and dust particles that would normally cause accelerated bearing wear. Analysis showed that engines with auxiliary filtration showed 60% less bearing wear after equivalent operating hours compared to standard engines. The cooling system modifications were equally sophisticated. The ventury cowl increased air flow through the radiator by approximately 45% at speeds above 15 mph.

At lower speeds, the ventury effects still provided 20 to 30% increased air flow compared to standard configuration. The hood louvers vented hot air from the engine compartment while the angled design prevented dust ingress. Combined effects reduced operating temperature by 15 to 22° F under equivalent load conditions. The mathematics of Henderson’s modifications were elegant.

Each modification addressed a specific failure mode while also providing secondary benefits. Increased oil capacity improved both thermal management and contamination tolerance. Improved oil flow enhanced both lubrication and heat transfer. Better filtration reduced both wear and oil contamination. Enhanced cooling reduced both operating temperature and thermal stress.

This multi-function design approach maximized benefits while minimizing added complexity. Henderson hadn’t just piled on modifications hoping something would work. He’d carefully selected modifications that addressed multiple problems simultaneously. This efficient approach to problem solving reflected his agricultural engineering background where solutions needed to be effective, reliable, and simple enough to maintain with limited resources.

The training manual that resulted from Henderson’s work became standard instruction material for vehicle maintenance personnel. The manual titled Field Modifications for Enhanced Vehicle Reliability Under Combat Conditions devoted 63 pages to principles derived from Henderson’s designs. It emphasized that maintenance wasn’t just about following procedures, but about understanding why procedures existed and when they needed to be modified.

The manual included detailed instructions for fabricating cooling system improvements using available materials, modifying oil systems to increase capacity and flow, implementing auxiliary filtration using components from other vehicles, and calculating optimal specifications for specific operating conditions.

Mechanics studying the manual often commented that it taught them to think about vehicle systems rather than just replace components. But the manual’s most important section dealt with the mindset required for effective field maintenance. It stated, “Standard maintenance procedures assume parts availability, proper tools, and time for careful work.” Combat conditions rarely provide these luxuries.

Effective combat mechanics must understand system principles well enough to develop improvised solutions using available materials. The goal is not perfection according to specifications, but functionality under actual conditions. This principle of functionality over specification influenced broader military maintenance doctrine.

The concept that combat maintenance required different thinking than garrison maintenance became fundamental to training. Henderson’s jeep provided proof that improvised solutions could exceed standard procedures in military value. German prisoners interrogated after the war occasionally mentioned American vehicle reliability as a factor affecting their combat effectiveness. One German mechanic stated, “We constantly struggled with vehicle breakdowns.

Our trucks and halftracks required frequent maintenance that we couldn’t provide during combat operations. The Americans seem to have vehicles that continued operating even without proper maintenance. This mobility advantage allowed them to maintain offensive pressure when we were immobilized by mechanical failures. This mobility advantage was partly psychological.

German forces expecting American vehicles to be as unreliable as their own vehicles found instead that American units maintained operational tempo despite sustained combat. The uncertainty about whether American forces could be stopped by attrition of vehicles created hesitation that American commanders exploited. Jacob Henderson continued serving through the war’s end.

participating in operations through Italy, southern France, and into Germany. He was promoted to sergeant in January 1944 and to staff sergeant in August 1944. His personnel file noted, “Exceptional mechanical aptitude and problem solving ability, develops practical solutions to complex technical problems using available resources and innovative thinking.

” After the war, Henderson returned to Nebraska and took over his family’s farm. He ran the operation for 46 years, becoming known regionally for keeping equipment running long past its expected service life. Neighboring farmers would bring him equipment that other mechanics had declared unrepable, and Henderson would usually have it running within a day or two using improvised parts and creative solutions.

In a 1988 interview, Henderson reflected on his famous Jeep engine. People always wanted to know the technical details. What modifications did you make? How did you calculate specifications? But that’s not really what made it work. What made it work was understanding that military specifications were designed by engineers in offices who’d never seen combat conditions.

Good specifications for peaceime, wrong specifications for war. Once you understood that, the modifications were obvious. This philosophy of questioning specifications rather than blindly following them influenced multiple fields beyond military maintenance, manufacturing, quality control, product design for harsh environments, and systems engineering all incorporate principles that Henderson applied to his Jeep engine.

The idea that specifications should match actual use conditions has become fundamental to modern engineering. The engine’s legacy extends beyond technical achievements. It demonstrated that individual soldiers with specialized knowledge could develop solutions more effective than institutional approaches.

Henderson wasn’t following maintenance manuals when he rebuilt his engine. He was applying principles he’d learned on his family’s farm to problems he encountered in combat. This bottomup innovation proved more effective than top-down standardization in combat conditions. Military organizations naturally favor standardized procedures that ensure consistent results across large forces, but standardization assumes that central planners understand conditions better than soldiers in the field. Henderson’s engine proved this assumption wrong. Sometimes soldiers

facing actual conditions understand problems better than engineers working from peaceime specifications. The mockery Henderson endured before his engine proved itself reveals how institutions resist unconventional approaches. His mechanics, his sergeant, his captain, all dismissed his work because it didn’t conform to their expectations of proper procedure.

They valued compliance with specifications over effectiveness under actual conditions. Only when results became undeniable did attitudes change. 120 mi of continuous operation while every standard engine failed provided proof too dramatic to dismiss. But if the battalion hadn’t conducted that long movement, if Henderson’s engine hadn’t been tested against standard engines under identical conditions, his modifications might have remained dismissed as farmboy tinkering.

The mechanics who mocked Henderson’s work were professionals trained in proper procedures. They knew how engines were supposed to be maintained according to technical manuals. But their training hadn’t prepared them for the reality that specifications designed for peacetime garrison conditions didn’t work under combat field conditions.

They were following correct procedures that produced incorrect results. This is institutional failures harsh reality. Correct procedure matters less than correct results. The mechanics who ridiculed Henderson probably believed they were protecting proper standards. But standards that cause equipment failure aren’t worth protecting.

Results matter more than procedure. Modern military maintenance doctrine incorporates many principles demonstrated by Henderson’s Jeep. The concept of field modifications to improve reliability, designing for worst case conditions rather than ideal specifications.

Using component compatibility to create improvised solutions, and prioritizing operational readiness over procedural compliance are all standard elements of contemporary maintenance practice. Every military mechanic who modifies equipment to improve performance today applies principles that one farm boy figured out in a Sicilian motorpool in July 1943. The engine also demonstrated the importance of understanding underlying principles rather than just following procedures.

Henderson succeeded because he understood why engines failed and how to prevent failures. Other mechanics failed because they knew what procedures to follow, but not why those procedures sometimes weren’t adequate. This combination of theoretical knowledge and practical experience separated Henderson from other mechanics. Many new procedures, many had experience. Few combined both with confidence to develop solutions that violated specifications and patience to endure ridicule while proving those solutions worked. They mocked his farmboy engine fix.

Called it Henderson’s hillbilly engine abortion, a violation of proper procedure. They said it would fail within 50 m. That farm techniques didn’t apply to military vehicles. That specifications existed for good reasons. They threatened court marshall if he didn’t install a standard engine.

Then his jeep outlasted every vehicle in the battalion and the mockery stopped. The engine operated for 600 hours before first overhaul, double the standard interval. Enabled vehicle availability rates 75% higher than standard. created force multiplication effects that improved operational tempo and demonstrated principles that influenced military vehicle design for decades.

All because one farm boy refused to accept that specifications designed for peaceime were adequate for war. Jacob Henderson proved that sometimes the farm boy fix isn’t ignorant tinkering. Sometimes it’s sophisticated engineering disguised as improvisation, waiting for circumstances to reveal its true effectiveness.

Sometimes innovation requires trusting practical experience over theoretical specifications. The Germans never understood why American vehicles were so reliable. The army eventually recognized that Henderson’s modifications were superior to standard specifications. But really, it was proof that one person with practical knowledge, theoretical understanding, and absolute conviction can achieve results that entire institutions never imagined.

They mocked his farm boy engine fix until his Jeep outlasted every vehicle. Then they stopped mocking and started learning. and military maintenance changed because one farm boy understood that effectiveness matters more than compliance, that results matter more than specifications, and that innovation requires courage to violate procedures when procedures are wrong.

The hillbilly engine wasn’t hillbilly engineering. It was sophisticated mechanical design based on agricultural principles. And in 600 hours of continuous operation, it proved that sometimes the greatest innovations come from the least expected sources when someone has courage to trust their knowledge over institutional authority.

Henderson’s Jeep is preserved at the National World War II Museum in New Orleans. The placard describes it as an example of field modification that influenced post-war vehicle design. But the real story is simpler and more profound. One farm boy refused to accept that engines had to fail.

And because he refused to accept failure, he built an engine that didn’t fail. That’s not just engineering. That’s the spirit that wins wars.

News

CH2 They Sent 40 ‘Criminals’ to Fight 30,000 Japanese — What Happened Next Created Navy SEALs

They Sent 40 ‘Criminals’ to Fight 30,000 Japanese — What Happened Next Created Navy SEALs At 8:44 a.m. on June…

CH2 What Japanese High Command Said When They Finally Understood American Power Sent Chill Down Their Spines

What Japanese High Command Said When They Finally Understood American Power Sent Chill Down Their Spines August 6, 1945….

CH2 “It’s Their Party, Don’t Look!” German POWs Smell BBQ – Cowboys Ordered Them to Join

“It’s Their Party, Don’t Look!” German POWs Smell BBQ – Cowboys Ordered Them to Join August 19th, 1945. The war…

CH2 Street Smart Outclassed Training – How One Baseball Question Exposed Germany’s Secret Infiltrators Dressed as GIs

Street Smart Outclassed Training – How One Baseball Question Exposed Germany’s Secret Infiltrators Dressed as GIs December 16th, 1944….

CH2 German POWs Were Shocked By America’s Industrial Might After Arriving In The United States

German POWs Were Shocked By America’s Industrial Might After Arriving In The United States June 4, 1943. The air…

Dad Threw His Napkin Down And Yelled, “You’re The Problem. Not Like Your Sister. She Actually Contributes.” I Laughed And Said, “Then Why Is She Acting Like A Vulture…” Dad Froze Mid Breath. Mom Dropped Her Fork. And My Sister…

Dad Threw His Napkin Down And Yelled, “You’re The Problem. Not Like Your Sister. She Actually Contributes.” I Laughed And…

End of content

No more pages to load