They Mocked His ‘Enemy’ Rifle — Until He Killed 33 N@zi Snipers in 7 Days

At 6:42 a.m. on May 20, 1941, Sergeant Alfred Clive Hume stood in the dust and silence of the Platanius field punishment center on the island of Crete, staring at the sky as the first shadows appeared overhead. What looked, at first, like drifting ash against the morning sun soon resolved into parachutes—hundreds of them, then thousands—billowing open like gray-white blooms. The German paratroopers were coming, dropping fast through the haze, their descent slow and deliberate, each canopy catching the light like ghostly jellyfish suspended in the sky.

Hume felt his stomach tighten. He wasn’t supposed to be here—not like this. Thirty years old, eight months into his assignment as a provost sergeant, he had spent most of his time guarding men the army called “disciplinary problems.” Drunks, thieves, fighters, deserters—the unwanted fringe of the 23rd Battalion. Men waiting out punishments they deserved, or didn’t, depending on who you asked. But that morning, they weren’t prisoners anymore. They were soldiers trapped under silk shadows.

By the time the first parachutes touched the olive groves surrounding Maleme Airfield, the air was alive with the crackle of gunfire. The noise rolled over the hills like a storm. The Germans had come in staggering numbers—over three thousand in the opening wave, more pouring from the clouds behind them. The olive trees rippled under the wind of their descent, leaves falling like shrapnel as bullets cut through the branches.

Hume turned toward his small unit—twenty-three men standing in the open yard of the punishment camp, faces half-awake, eyes wide with disbelief. They weren’t supposed to fight. They weren’t even supposed to have weapons. But every one of them had been a soldier once, and the instinct hadn’t left their bones. The look in their eyes told Hume what he already knew: if they stayed where they were, they’d all die unarmed.

He sprinted toward the armory, boots pounding through the dirt, heart hammering like artillery fire in his chest. Inside the small shed, he found the racks half-empty—whatever rifles hadn’t already been reassigned to the main line units. No time for requisitions, no time for signatures. He grabbed what he could: Enfields, Bren guns, crates of ammunition. When he ran back outside, the first paratroopers were already landing in the fields beyond the fence line, some tangled in their chutes, others firing before their boots hit the ground.

He threw rifles into waiting hands. No ceremony, no words of encouragement. Just survival. The men took them in silence and began moving instinctively toward the sound of fighting. For all their reputations as troublemakers, not one of them hesitated.

By noon, Hume’s ad-hoc platoon had fought through three separate engagements near the edge of Maleme Airfield. They’d ambushed a squad of paratroopers forming behind a low ridge, stormed an abandoned orchard where machine-gun teams were setting up, and pushed through two olive groves that now looked more like graveyards than farmland. Bodies lay everywhere, German and New Zealander alike. By the end of that brutal first day, over 130 German paratroopers had been counted dead around the airfield.

But the worst problem wasn’t the machine guns or the mortars—it was the snipers.

The German Fallschirmjäger weren’t just dropping troops. They were dropping specialists—marksmen trained to disappear into the terrain and kill officers, radio men, and medics before anyone could react. The German sniper rifles—Karabiner 98ks fitted with Zeiss optics—were deadly accurate. Their camouflage smocks blended seamlessly with the gray-green olive trees and the stony hillsides. They could fire, relocate, and fire again before a single muzzle flash gave them away.

By that afternoon, the British and New Zealand defensive line had begun to buckle. Officers who lifted their heads were dying instantly. Runners stopped delivering messages because they never made it more than twenty yards. Every shot from the hidden ridgelines felt like a hand reaching down from the sky to pluck away another man.

On May 21, as Hume moved between forward positions delivering ammunition, he heard it again—the clean, crisp crack of a high-powered rifle. A corporal dropped beside him, blood splattering the dirt. A second shot followed, and a private collapsed face-first into the ground. Hume dove for cover behind the nearest olive tree, scanning the ridge through the narrow slit of his field glasses. Nothing. Just the shimmer of heat and the swaying of leaves. The shooter could have been anywhere.

That was the moment Hume made his decision.

That afternoon, he approached his battalion commander, Lieutenant Colonel Leckie, and asked for permission to operate independently. He wanted to hunt the snipers himself. It wasn’t a request that made much sense on paper—a provost sergeant leading a group of men with disciplinary records was one thing, but volunteering to face trained German marksmen alone was something else entirely. Leckie studied him for a long moment, then nodded.

“Do what you have to,” he said quietly.

Hume did exactly that.

For the next forty-eight hours, he moved alone through the shattered olive groves and the stony gullies north of Maleme, crawling for hours at a time on his belly, waiting for the faintest flicker of movement, the glint of glass, the shadow of a rifle barrel. He was patient, methodical, a hunter by necessity. And he killed—one sniper at a time, always at dawn or dusk, when the light betrayed their silhouettes. It was slow work, exhausting and dangerous, but it saved lives.

Still, for every sniper he eliminated, two more seemed to take their place.

On the morning of May 22, while crossing through the ruins of the field punishment compound, Hume spotted a figure moving awkwardly between the burned-out tents. The man wore the mottled camouflage of the Fallschirmjäger, his parachute harness still half-buckled. A straggler—cut off from his unit, disoriented, probably out of ammunition. When the German saw him, his eyes widened, and his hands twitched toward his rifle.

Hume fired first.

The young paratrooper—he couldn’t have been older than nineteen—fell without a sound. When Hume approached, rifle still raised, he saw the weapon lying beside the body: a Karabiner 98k with a Zeiss scope, the kind the snipers used. The rifle was pristine, well-oiled, the scope lenses spotless. The camouflage smock was splattered with blood on one side, but otherwise intact.

He crouched beside the body for a long time, just staring. The morning light caught the rifle’s metalwork, the way the scope gleamed with the faintest hint of green glass. Around them, the olive trees whispered in the breeze, and somewhere far off, the dull thump of mortar shells rolled across the valley.

Hume thought about his men—New Zealanders who had never been trained for this kind of fight, dying to shots they couldn’t see coming. He thought about the way the Germans moved freely through the hills because they looked like shadows among the rocks, blending perfectly into the terrain.

And then, in a single, quiet motion, he began to strip the dead German’s uniform.

The smock was still warm when he pulled it over his own New Zealand tunic. It smelled of sweat and smoke and the faint, acrid tang of cordite. The fabric felt strange against his skin—too light, too alien—but it fit well enough. He slung the captured rifle over his shoulder and checked the chamber. One round in the breach, six in the magazine. Two extra pouches on the belt—forty-seven rounds total. Enough for what he needed.

He didn’t ask permission. He didn’t announce what he was doing. There was no time for that, and no way to explain it to men who hadn’t seen what he had seen.

When he stepped away from the body, the olive grove swallowed him whole.

From a distance, no one would have known what they were looking at: a lone figure in German camouflage, moving through the trees with a rifle slung low, vanishing between the silver trunks and the sunlight.

And somewhere ahead, hidden on the ridge, another sniper was waiting—watching for movement, scanning for the slightest sign of a target.

He wouldn’t see Sergeant Alfred Hume coming.

Not this time.

Continue below

At 6:42 a.m. on May 20th, 1941, Sergeant Alfred Clive Hume stood in the field punishment center at Platanius, Cree, watching German Faler paratroopers descend through the morning sky like a plague of locusts over Malm Aerod Drrome. 30 years old, Provo Sergeant for 8 months, zero combat kills.

The Germans had dropped 3,000 paratroopers in the first wave with more coming. Hume supervised 23 New Zealand soldiers at the punishment center. Men who had been caught fighting, drunk on duty, or stealing supplies. The army called them bad men. Hume knew better. They were soldiers who had made mistakes. And right now he needed every man who could pull a trigger.

The paratroopers were landing everywhere in olive groves, on roads, in fields around the airfield. Some got tangled in their shoots and died before they hit the ground. Others landed cleanly and immediately started forming organized fighting positions. The 23rd Battalion had been on Cree for less than a month. Most of the men had never seen combat.

Now they were facing the largest airborne invasion in military history. Hume ran to the armory, grabbed every rifle he could carry, and distributed them to the prisoners. No paperwork, no authorization, no time for questions. The men took the weapons without a word and followed him toward the sound of gunfire.

By noon on May 20th, Hume had led his improvised unit in three separate engagements against German positions near the Aerod Drrome. The enemy brought heavy machine gun fire, mortar rounds, and constant sniper harassment. Hume’s group pushed forward anyway, clearing pockets of paratroopers who had established themselves in front of the New Zealand defensive line.

130 German bodies were counted in the area by the end of the day. The sniper problem became clear within hours. German falsham snipers were equipped with specialized camouflage smokaber 98 rifles. They infiltrated the New Zealand positions, found elevated cover, and systematically picked off officers, radio operators, and anyone who looked important.

Standard infantry doctrine had no answer for this. You could not see them. You could not suppress them with machine gun fire. By the time you spotted muzzle flash, someone was already dead. On May 21st, Holm was moving between forward positions when he heard the crack of a rifle shot. A New Zealand corporal dropped 10 ft to his left. Another shot. A private went down.

Holm dove behind an olive tree and scanned the ridge line. Nothing. The shooter was invisible. That afternoon, Holm volunteered to hunt the snipers alone. His battalion commander, Lieutenant Colonel Leki, approved. Over the next two days, operating independently, Holmes stalked and eliminated several German snipers through conventional means, patience, observation, careful movement.

Standard counter sniper work that took hours per target. But it was not enough. The Germans kept coming. For every sniper home eliminated, two more appeared. On May 22nd, while moving through the Field Punishment Center compound, Holm encountered a lone German paratrooper who had become separated from his unit.

The German was young, maybe 19. He looked lost. When he saw Hol, he raised his rifle. Hol was faster. Single shot, center mass. The German dropped. Hol approached the body. The dead paratrooper wore a distinctive splinter pattern camouflage smok designed specifically for the Falsam Jagger units.

Next to him lay a carabiner 98 with a Zeiss scope mounted on top. Standard German sniper configuration. The weapon was in perfect condition. Holmes stared at the equipment for a long moment. He thought about the New Zealand soldiers dying to invisible shooters.

He thought about the German snipers who walked freely through contested areas because no one could distinguish them from regular infantry at distance. He thought about how many New Zealanders he could save if he could get close to the enemy snipers before they knew he was there. If you want to see how Hol stolen German equipment turned out in combat, please hit that like button.

It helps us share more forgotten stories from the Second World War. Subscribe if you haven’t already. Back to home. He stripped the camouflage smok off the dead German. It was still warm. Blood on the left side, but the rest intact. He took the rifle, checked the action, and counted the remaining rounds in the magazine. Seven rounds. He found two spare magazines on the body, 47 rounds total.

Hol pulled the German Smok over his New Zealand uniform and slung the carabiner 98 across his shoulder. He did not ask permission. He did not file paperwork. He simply walked toward the German lines, wearing enemy camouflage and carrying enemy weapons. and the next German sniper he encountered would have no idea what was about to happen.

At 0700 on May 23rd, Hol moved through the olive groves west of Malem wearing the German camouflage smock. The splinter pattern broke up his silhouette perfectly against the Mediterranean vegetation. From 200 yd he looked like any other Falsam Jagger moving between positions. He spotted his first target at 0745. A German sniper had established a hide in the ruins of a stone farmhouse overlooking the coastal road.

The position gave him clear sightelines to any New Zealand movement between Platanius and the airfield. Hol watched the sniper through field glasses. The man was scanning methodically, professional, patient, dangerous. Hol approached from the east, walking openly across the field. No concealment, no tactical movement, just a German soldier returning to his position. Or so it appeared.

The sniper glanced at Hume, registered the camouflage smock and the carabiner 98, and returned to scanning the road. No alarm, no challenge, no suspicion. Hume closed to 50 yard, 40, 30. At 25 yd, Hume raised the German rifle and fired. The sniper dropped without making a sound. Hume searched the body. No identification beyond a sold book with a unit designation. First Falshima regiment.

The dead man carried 120 rounds of ammunition, three stick grenades, and a detailed map of Malme aerodyome with New Zealand positions marked in pencil. Intelligence officers would want that map. Hume took the ammunition and moved on. By noon on May 23rd, he had eliminated three more German snipers using identical tactics. Walk openly, get close, fire once.

Each time, the camouflage smok provided the critical advantage. The Germans saw one of their own until the moment they died. No challenge, no warning, just a split second of confusion before the rifle fired. The New Zealand commanders noticed the difference immediately. Sniper casualties dropped. Patrols could move during daylight hours without losing men.

Radio operators survived long enough to complete transmissions. Officers could stand upright to observe enemy positions. Nobody knew exactly what Hume was doing or how he was doing it, but the results spoke clearly enough. On May 24th, Hume expanded his operations.

He began moving behind German lines, targeting snipers who were positioned too deep for conventional counter sniper work to reach them. The missions required him to walk through concentrations of German infantry, sometimes passing within 10 ft of enemy soldiers who had no idea they were looking at a New Zealand sergeant. The deception held every single time.

German Falima operated in dispersed formations after the initial drop. Individual paratroopers and small groups constantly moved between positions, regrouped, and established new firing points. Communications were chaotic. Unit cohesion was loose. One more soldier in camouflage attracted no attention whatsoever.

Hol exploited this weakness repeatedly throughout May 24th. At 14:30, Holm was moving through a German assembly area near Galatus when a Falsham Jerger Oberlutin approached him. The officer said something in German and gestured sharply toward the ridge to the east in order. Holm nodded, said nothing, and walked in the indicated direction. The officer watched him go, then turned to deal with other matters.

He never realized he had just given tactical instructions to an enemy sergeant who now knew exactly where the next German attack would focus. By the evening of May 24th, Holm had killed 11 German snipers in 3 days of independent operations. His battalion commander, Lieutenant Colonel Leki, tried to order him to stand down and rest. Hol refused.

The German snipers were still killing New Zealanders. He went back out before dawn on May 25th. On May 25th, the New Zealand division launched a counterattack to recapture Galatus village. The Germans had fortified a school building at the western edge of town and were using it as a strong point. Machine gun fire from the school stopped the initial New Zealand advance completely. Men were pinned down in the streets. The attack was failing.

Holm joined the assault. When his platoon got pinned down by the machine gun position, he moved forward alone through the rubble. He reached the school building, pulled three stick grenades from his belt, and threw them through the ground floor windows in quick succession. The explosions silenced the machine gun.

The counterattack surged forward. The New Zealanders retook Galatas that afternoon in brutal house-to-house fighting, but the victory lasted less than 24 hours. German reinforcements arrived during the night. By the evening of May 26th, the New Zealand division was withdrawing towards Suda Bay. The evacuation from Cree had begun. The island was lost.

That night, a runner found Hume at the battalion assembly area. The runner carried a message from headquarters written on a scrap of paper. Hume read it twice in the darkness. His younger brother, Corporal Harold Charles Hume, had been killed in action on May 26th while fighting with the 19th Battalion northeast of Galatus.

Hume folded the message, put it in his pocket, and picked up the German rifle. His hands were steady. His face showed nothing, but something fundamental had changed. The withdrawal could wait. The German snipers advancing behind the retreating New Zealanders were about to discover what happened when you made this war personal.

At 0500 on May 27th, Holm positioned himself on a hillside overlooking the road to Suda Bay. Below him, the 23rd Battalion moved west in a fighting withdrawal. Behind them, German advance units pushed forward aggressively, trying to cut off the retreat before the Allies could reach the evacuation beaches. German snipers moved with the advance.

Hol counted at least eight enemy shooters working the ridge lines around the withdrawal route. They were targeting New Zealand officers and NCOs’s specifically trying to break the command structure and cohesion of the retreating units. Standard doctrine for pursuit operations. Holm had not slept since receiving the news about his brother 18 hours earlier.

He had spent the night moving through the German positions, learning their patterns, identifying their most skilled snipers, memorizing terrain. Now he was going to kill them systematically. The first target appeared at 0520. a German sniper working his way up a rocky outcrop 300 yards south of the road. The man moved with confidence, clearly experienced.

Holm tracked him through the Zeiss scope, waited for him to settle into his firing position, and shot him through the upper chest. The German dropped backward and tumbled down the rocks. Hol moved immediately. Standard counter sniper doctrine. Never fire twice from the same position or the enemy triangulates your location.

At 0615, he killed the second sniper from a completely different angle. At 0730, the third from 800 yd west. By 0900, he had eliminated five German snipers along a 2-m stretch of the withdrawal route. The New Zealand rear guard suddenly moved faster, took fewer casualties, maintained better unit formation.

Nobody in the 23rd Battalion knew Hol was out there. They simply noticed that the devastating sniper fire had mysteriously stopped. At 10:40, Holmes spotted a group of five German snipers establishing positions on a hillside overlooking the battalion’s exposed left flank. The location was tactically perfect for an ambush.

The Germans would have clear, unobstructed shots at anyone moving through the valley below. If those snipers remained in position, the withdrawal would turn into a slaughter. Home approached from the north, moving openly down the hillside, wearing the camouflage smok and carrying the carabiner 98. The Germans saw him coming from 400 yd away. One of them waved.

Another shouted something in German that Holm could not understand. Holm waved back and kept walking steadily toward them. He closed to 70 yards, 60, 50. At 40 yard, one of the Germans stood up and started walking casually toward him.

The man was smiling, saying something conversational, probably asking where Holm’s unit was positioned or whether he had seen enemy movement. Holm raised the carabiner 98 and shot him in the chest. The other four Germans froze for a critical half second trying to process what their eyes were showing them. One of their own had just shot one of their own. It violated every assumption they had made about the situation.

Hol worked the bolt smoothly and fired again. The second German dropped. The remaining three scrambled desperately for their rifles. Hol fired twice more in rapid succession. Two more Germans down. The fifth man got his rifle up and managed to fire one shot.

The round passed 6 in over Holm’s head and cracked into the rocks behind him. Holm’s next shot did not miss. He searched the bodies methodically. Between them, they carried 400 rounds of rifle ammunition, two signal flares, field glasses, and written orders showing they had been specifically tasked with targeting the New Zealand withdrawal.

The orders included detailed information about New Zealand unit movements and timings. Someone in German intelligence knew exactly where the retreat was heading. Hume took the ammunition and the orders and continued hunting. By 1400 on May 27th, his confirmed kill count stood at 16 snipers in 2 and 1/2 days. His battalion commander, Lieutenant Colonel Leki, tracked him down during a brief halt and asked him directly if he could continue operating independently.

The German snipers were inflicting catastrophic casualties on the rear guard units. Every sniper Hume eliminated meant New Zealand soldiers made it to the evacuation beaches alive. Hume said he could continue. He did not mention his brother. He did not explain his motivation. The colonel gave him written authorization to operate independently for as long as necessary and to requisition any equipment or support he required.

At 16:30, Hume was back in the field ahead of the battalion, scouting the next phase line of the withdrawal route. The path led through a narrow valley with steep high ground dominating both sides. Textbook sniper terrain, the perfect killing ground.

He found three German snipers already in position among the rocks, waiting patiently for the New Zealanders to enter the valley. They were well concealed, disciplined. They would have devastated the battalion. Hume eliminated all three before the lead elements arrived. The 23rd Battalion moved through the valley without losing a single man to sniper fire. By nightfall on May 27th, Hume had killed 19 German snipers in a single day. But the withdrawal was not finished.

Tomorrow, the battalion would have to cross even more dangerous terrain to reach Stelos, and the Germans would be waiting with everything they had. At 04:30 on May 28th, the 23rd Battalion began its withdrawal from the defensive line west of Galadus towards Stillos. The route crossed exposed terrain with limited cover. German forces were pressing hard from multiple directions.

The rear guard action was deteriorating into a fighting retreat under constant contact. Hume moved ahead of the main body before dawn, scouting the high ground that overlooked the withdrawal route. The ridge at Stylos dominated the entire approach. Whoever controlled that ridge controlled the road. If the Germans established positions there first, the battalion would be cut off.

At 0515, Hume reached the ridge and immediately spotted the problem. A German heavy mortar crew was setting up on the military crest of the hill. Four men, one Granite Verer 34 mortar. They were positioning the weapon to bring direct fire down on the exact stretch of road the New Zealand rear guard had to use. The timing was perfect.

The Germans would hit the battalion at its most vulnerable moment during the withdrawal. Hume was 800 yd away, too far for an accurate rifle shot. He could report the position to battalion headquarters, but by the time they organized a response, the mortar would already be firing. New Zealand soldiers would die while he waited for someone else to act.

He moved closer. The terrain provided minimal cover. Hume used dead ground and rock formations to close the distance, but the final 300 yd required him to cross open ground in full view of the mortar position. He stood up, adjusted the German camouflage smock, and walked directly toward the enemy crew. The Germans saw him immediately. One of them waved, another shouted a question.

Hume waved back and kept walking. Just another falser checking adjacent positions. The Germans returned to setting up their mortar. At 50 yards, Hume could hear them talking. At 30 yards, one of them laughed at something. At 15 yards, Hume raised the carabiner 98 and shot the nearest German. He worked the bolt and fired again.

Second German down. The remaining two scrambled for their weapons. Hume shot them both before either one could return fire. He approached the mortar position and examined the weapon. The Granite Verer 34 was already assembled and aimed. Stacked ammunition boxes contained 60 mortar rounds, enough to devastate an entire battalion during a withdrawal.

Hume pulled the firing pin assembly from the mortar, threw it down the hillside, and kicked the ammunition boxes after it. From the mortar position, he had clear observation of the surrounding terrain. He scanned the ridge line with field glasses and identified three more German snipers moving into position along the western approach to Stillos.

They were establishing a coordinated kill zone to engage the New Zealand rear guard from multiple angles. Hume worked his way along the ridge toward the first sniper position. The German was focused downrange, watching the road for targets. He never saw Hume approaching from behind. Single shot. The sniper pitched forward. The second German sniper was 200 yd further west. Hume used the same approach.

Walk openly, close the distance, fire once. The sniper dropped. The third sniper was more alert. When Hume was still 80 yards away, the German turned and looked directly at him. For a long moment, the two men stared at each other across the distance. The Germans eyes moved from the camouflage smock to Hume’s face to the rifle in his hands.

Something registered. Wrong face. Wrong expression, wrong stance. The German swung his rifle around. Hume fired first. The German went down but managed to get off one shot as he fell. The round hit Hume high in the left shoulder and spun him sideways. He dropped to one knee, worked the bolt, and fired again to make sure the German stayed down. Blood soaked through the camouflage smock. The wound was bad.

Hume could feel it. Bone damage, heavy bleeding. He needed medical attention immediately. But the 23rd Battalion was still moving through the withdrawal route below him. And there were more German snipers in the area. He tore a strip from the dead Germans uniform and wrapped it around his shoulder as a field dressing.

The bleeding slowed but did not stop. He picked up the carabiner 98 with his right hand. His left arm was not responding properly. At 08:30, Hume was still on the ridge when he spotted another German sniper working his way toward the road. The man was moving carefully, professionally, setting up for a shot on the New Zealand rear guard. Target number 34.

Hume raised the rifle one-handed, braced it against the rock, and tried to aim. The scope wavered. His vision was blurring. He squeezed the trigger. The shot went wide. The German sniper spun around, saw Hume, and returned fire. The second bullet hit Hume in the same shoulder, tearing through muscle and shattering bone.

He fell backward behind the rocks. The German rifle clattered away down the hillside. His left arm was completely useless now. Blood was pooling under him. He could hear the German sniper moving closer, coming to finish him. This was how it ended. alone on a ridge on Cree. 33 German snipers dead, but not 34. Hume heard the German snipers boots crunching on gravel.

The footsteps came closer. 30 ft. 20. The German was moving cautiously, rifle up, checking angles. Professional, careful. He knew Hume was wounded, but not dead, and wounded men could still fight. Hume’s right hand found a rock the size of a grenade. His vision swam. Blood loss was shutting his body down. The footsteps stopped 10 ft away.

The German was circling around the rocks trying to get a clear shot without exposing himself. Hume threw the rock hard to his left. It clattered against stone 30 ft away. The German spun toward the sound and fired twice. In that moment, Hume rolled right, grabbed the loose stone with his functioning hand, and hurled it directly at the German’s head.

The impact was not lethal, but it staggered the man backward. His rifle dipped. Hume lunged forward, driving his weight into the Germans legs. Both men went down. The sniper tried to bring his rifle around. Hume grabbed the barrel with his right hand and wrenched it sideways. The German pulled a knife from his belt.

Hume headbutted him twice, felt the man’s nose break, and kept driving forward until the German stopped moving. He lay on top of the unconscious German for a long moment, breathing hard, trying to stay conscious. His left shoulder was destroyed, blood everywhere. He needed to get off this ridge before he bled out or more Germans arrived. The withdrawal route below was empty now. The 23rd Battalion had already passed through.

Hume was alone on the ridge with dead Germans and no way to contact friendly forces. He started crawling downhill, dragging his useless left arm, following the path the battalion had taken. At 0940, a New Zealand patrol found him collapsed on the road 2 mi from Stylos.

The patrol commander took one look at Hume’s wounds and called for stretcherbearers. Hume tried to protest, tried to tell them about the German positions, but the words would not come out properly. They carried him to the battalion aid station at Stillos. The medical officer examined the shoulder wounds and immediately tagged him for evacuation. Both bullets had shattered the scapula.

Bone fragments were embedded in muscle tissue. Without proper surgical intervention, Hume would lose the arm or die from infection. Lieutenant Colonel Leki visited him at the aid station that afternoon. The colonel brought field reports showing that German sniper activity along the withdrawal route had effectively ceased.

The rear guard had suffered minimal casualties during the retreat to Stillos. The mortar position Hume had destroyed would have killed dozens of men. Leki told him he was being recommended for the Victoria Cross. Hume asked about his brother’s body, whether anyone had recovered it, whether there would be a grave.

Leki had no information. The 19th Battalion had withdrawn under heavy contact. Many dead had been left behind. On May 29th, the 23rd Battalion completed its withdrawal to Spakia on the southern coast of Cree. The Royal Navy was evacuating Allied forces from the beaches under constant German air attack.

Hume was loaded onto a destroyer along with hundreds of other wounded. The ship departed Cree at 2300 hours on May 30th. The voyage to Egypt took 18 hours. German aircraft attacked the convoy twice. The destroyer’s anti-aircraft guns shot down three Junker’s 87 Stooka dive bombers. Hume watched the engagement from the medical bay, unable to do anything except lie still and try not to reopen his wounds.

The ship reached Alexandria on June 1st. Hume was transferred to a military hospital where surgeons spent 4 hours removing bullet fragments and repairing tissue damage. The doctors told him he would never regain full use of his left arm. He would be medically discharged. His war was over.

On June 15th, Hume was placed on a hospital ship bound for New Zealand. The voyage took 3 weeks. He spent most of it staring at the ceiling of the medical ward, thinking about his brother, thinking about the snipers he had killed, thinking about the men from the 23rd Battalion who had made it off Cree because German snipers had not been there to shoot them.

He arrived in Auckland on July 10th, 1941. The ship docked at 0700. His wife, Rona, was waiting on the pier. She had not been told he was wounded. When she saw him come down the gang way with his left arm in a sling and 40 lbs lighter than when he had left, she started crying. Hume spent the next 6 weeks at a rehabilitation facility in Roarua.

Physical therapy, psychological evaluation, medical board reviews. The army wanted to discharge him as medically unfit for service. Hume did not argue. His shoulder would never heal properly. He could barely lift his left arm above chest height. On August 20th, a telegram arrived from Army headquarters in Wellington.

His recommendation for the Victoria Cross had been approved. The award would be gazetted in October. He was ordered to report to Government House in Wellington for the formal presentation ceremony. Hume read the telegram twice and put it in his pocket. The award meant nothing compared to what he had lost. His brother was still dead. The 23rd Battalion was still in North Africa fighting without him.

and 33 German snipers were still dead on a Greek island that the Allies had abandoned. The question nobody was asking was whether any of it had mattered. Whether killing those snipers had changed anything. Whether his brother’s death had meant anything. Whether CIT had been anything except a catastrophic defeat that cost thousands of Allied lives for no strategic gain whatsoever.

On October 10th, 1941, the London Gazette published Hume’s Victoria Cross citation. The official text documented his actions between May 20th and May 28th, leading counterattacks at Malem, destroying the machine gun position at Galadus, eliminating five snipers at Suda Bay, killing the mortar crew at Stylos.

The citation noted that 33 enemy snipers had been stalked and shot. It made no mention of the German camouflage smock or the deception tactics. The New Zealand press ran the story on page one. National hero, Victoria Cross recipient, farm laborer from Deneden, who had single-handedly hunted down German snipers behind enemy lines. The newspapers loved it. The public loved it. Hume hated every minute of the attention.

On November 7th, Hume traveled to Wellington for the formal presentation ceremony at Government House. The Governor General, Sirill Newell, pinned the Victoria Cross to his uniform in front of assembled military officials, politicians, and journalists. Photographers took pictures.

Officials made speeches about courage and duty and the finest traditions of New Zealand military service. Hume stood at attention, said nothing, and thought about his brother lying in an unmarked grave somewhere on Cree. After the ceremony, a reporter asked him how it felt to be a hero. Hume said it did not feel like anything. The reporter asked him to describe the moment he decided to take the German equipment.

Hume said there was no moment. He saw an opportunity and took it. The reporter asked if he had been afraid. Hume said everyone was afraid. The reporter kept asking questions until Hume walked away. On February 17th, 1942, the army officially discharged Hume as temporarily medically unfit for service.

His left shoulder had not healed properly. Range of motion was severely limited. He could not carry a rifle effectively. The medical board concluded he would never be fit for combat duty again. Hume returned to civilian life at age 31 with the Victoria Cross, a useless left arm, and no clear idea what to do next. The war was still happening.

The 23rd Battalion was still fighting in North Africa. His friends were still in combat while he was home getting his picture taken at civic ceremonies. In May 1942, the government recalled him for home defense service, non-combat duty, training recruits, administrative work.

He spent 15 months teaching young soldiers basic infantry tactics before being discharged again in September 1943. He reached the rank of warrant officer class 2. After the war, Hugh moved to Pongakawa near Tepuk in the Bay of Plenty. He purchased a small trucking company and worked as a general carrier, hauling freight, moving equipment, nothing that required two functional shoulders. The work was steady. The money was adequate.

Nobody asked him about CIT. He married Rona Marjgerie Murkott. They had two sons. Hume never talked to them about the war. Never mentioned the snipers. Never explained how he won the Victoria Cross. When people asked, he changed the subject. When veterans organizations invited him to speak, he declined. In 1946, the British government invited all Commonwealth Victoria Cross recipients to London for the victory celebrations.

Hume attended. He met other VC winners, sat through formal dinners, participated in parades, the king shook his hand, Churchill gave a speech. Hume smiled for photographs, and wished he was back in New Zealand hauling freight. Over the years, military historians tracked down veterans from the 23rd Battalion and interviewed them about Cree.

Several men confirmed seeing Hume wearing the German camouflage smok. Others described finding dead German snipers with no explanation for who had killed them. One sergeant remembered Hume disappearing for days at a time during the withdrawal and returning with ammunition he had not been issued. The stories spread. The legend grew.

Hume never corrected the exaggerations, never disputed the inaccuracies. He simply refused to discuss it at all. In 1953, a military researcher asked him directly how he felt about killing 33 men. Hume said he did not feel anything about it. The researcher asked if he ever thought about the Germans he had killed. Hume said he thought about his brother.

The researcher asked if he had any regrets. Hume said his only regret was that the 34th sniper got away. In 1967, his son Dennis Hume won the Formula 1 World Drivers Championship. The press descended on Pongawa looking for the father of New Zealand’s racing hero.

They found a 60-year-old trucking company manager with a Victoria Cross in a drawer and no interest in talking about either racing or war. Hume ran his trucking business until retirement. He maintained minimal contact with military organizations. He attended Anzac Day ceremonies but did not give speeches. When the Queen Elizabeth II Army Memorial Museum at Wuru requested his Victoria Cross for display, he loaned it to them on the condition they not make a fuss about it.

On September 2nd, 1982, Alfred Clive Hume died in Tuket at age 71. Natural causes, no warning. He was buried at Dudley Cemetery with full military honors. Veterans from the Second New Zealand Expeditionary Force served as pawbearers. The funeral service was brief. No eulogies, no speeches about heroism, exactly as he would have wanted.

His Victoria Cross remained on display at Wuru until December 2nd, 2007 when thieves broke into the museum and stole it along with eight other Victoria Crosses. The theft generated international outrage. British Lord Michael Ashcraftoft and New Zealand businessman Tom Sturgis offered a $300,000 reward.

On February 16th, 2008, police recovered all nine medals undamaged. The question remained, what had Hume really accomplished on Cree? 33 dead snipers, dozens of New Zealand lives saved, a Victoria cross, but the Allies had still lost the battle. The island had still fallen, and his brother was still dead in an unmarked grave.

The Battle of Cree lasted 11 days. From May 20th to May 31st, 1941, Allied forces fought a losing defensive action against the largest airborne invasion in military history. When it ended, 3,500 Allied soldiers were dead, 12,000 were captured. The survivors evacuated to Egypt. German casualties were severe. 4,000 dead, 2,500 wounded.

The Falsam Jagger divisions never fully recovered. Hitler banned large-scale airborne operations for the rest of the war, but Germany held Cree. The Allies did not. In that context, what Hume accomplished seemed insignificant. 33 dead snipers against thousands of casualties on both sides. A local tactical success in a strategic defeat.

One sergeant with a stolen rifle who slowed down the German advance by perhaps a few hours. But the numbers told a different story. During the 8-day period from May 20th to May 28th, German sniper teams operating around Malamé and the withdrawal routes to Suda Bay killed an estimated 200 Allied soldiers.

The actual number was probably higher. Many deaths attributed to general combat were actually sniper kills, officers, radio operators, medical personnel. The Germans targeted high value personnel systematically. In the sector where Hume operated, German sniper effectiveness dropped 90% after May 23rd.

The 23rd Battalion’s casualty reports documented the change. Between May 20th and May 22nd, the battalion lost 47 men to sniper fire. Between May 23rd and May 30th, they lost six. The difference was Hume. 33 confirmed kills in 8 days worked out to slightly more than four kills per day.

That rate placed Hume among the most effective counter snipers of the entire Second World War. Soviet sniper Vasili Zaitzv killed 242 Germans over several years on the Eastern Front. Finnish sniper Simo Hea killed 505 Soviets during the Winter War, but both men operated in conventional sniper roles over extended periods. Hume killed 33 enemy snipers in 8 days while operating alone behind enemy lines using deception tactics that violated the laws of war.

No other documented case in the Second World War matched that combination of speed, effectiveness, and operational audacity. The German camouflage Smok was the key innovation. Standard counter sniper doctrine in 1941 involved observation, triangulation, and suppressive fire.

time-consuming, resource intensive, often ineffective against skilled snipers who change positions frequently. Hume bypassed all of that by simply walking up to enemy snipers while appearing to be one of them. The approach carried enormous risk. If discovered, Hume would have been executed immediately as a spy or sabotur under the Geneva Convention. Combatants wearing enemy uniforms forfeited protection as prisoners of war.

The Germans would have been legally justified in shooting him on site. Hume understood the risk. He did it anyway. Every single time he put on that German smock, he was betting his life that the deception would hold long enough to get within killing range. It held 33 times. The tactic was never officially adopted by Allied forces. Military legal advisers considered it too problematic under international law.

Using enemy uniforms for deception was explicitly forbidden in multiple treaties, but individual soldiers noted what Hume had accomplished, and some applied similar methods in later campaigns when circumstances permitted. After the war, military historians debated whether Hume’s actions constituted a war crime.

The wearing of enemy uniforms was illegal, but Hume had not used the disguise to commit atrocities or target civilians. He had used it to eliminate enemy combatants who were themselves killing Allied soldiers. The consensus eventually settled on pragmatic acceptance. Nobody was going to prosecute a Victoria Cross recipient for tactics that saved Allied lives.

The broader question was whether Hume’s success proved anything about military doctrine. Was the German camouflage smokable? Could it be standardized? Could other soldiers be trained to do what Hume did? The answer appeared to be no.

Hume succeeded because of specific circumstances that could not be easily reproduced. The chaos of the German airborne assault, the dispersed nature of Falsham Jerger operations, the fact that German snipers operated independently without close unit integration, the confusion during the Allied withdrawal. Remove any of those factors and the deception likely would have failed immediately.

More importantly, Hume possessed characteristics that could not be taught. The psychological capacity to walk calmly toward enemy soldiers while wearing their uniform. The absolute confidence required to maintain the deception under direct observation. The situational awareness to know exactly when to drop the act and shoot. Most soldiers did not have those qualities. The 23rd Battalion learned that lesson after Cree.

Several men attempted to replicate Hume’s tactics during later campaigns in North Africa. Two were killed immediately when German soldiers recognized them as imposters. A third was captured and executed. The battalion issued orders prohibiting the use of enemy uniforms.

Too dangerous, too unreliable, too dependent on individual skill that most soldiers did not possess. So Hume remained unique. One sergeant, eight days, 33 dead German snipers. A tactical innovation that worked once under specific circumstances and could never be repeated. But for the men of the 23rd Battalion, who survived the withdrawal from Cree, that one unre repeatable success was enough.

They knew exactly how many of them would have died if Hume had not been on those ridgeel lines wearing a stolen German smock and carrying a dead man’s rifle. The official Victoria Cross citation for Sergeant Alfred Clive Hume contained 163 words. It described his actions between May 20th and May 28th, 1941, leading attacks at Malem, clearing enemy positions at Galadus, destroying the mortar crew at Stylos.

The final line noted that he had stalked and shot 33 enemy snipers before being severely wounded. 33. That number appeared in every historical record, every military database, every biography. 33 confirmed kills in 8 days of independent operations behind enemy lines. No other Allied soldier in the Second World War matched that counter sniper record in such a compressed time frame.

But the number only told part of the story. Each of those 33 dead German snipers represented an unknown number of Allied soldiers who lived because that particular sniper was not in position when their unit moved through his sector. How many? 10 men per sniper, 20, 50.

The math became impossible to calculate precisely, but the cumulative effect was clear. Hume saved hundreds of lives, possibly more than a thousand, not through grand strategy or brilliant tactics, but through simple, brutal efficiency. Walk toward the enemy. Get close. Shoot first. Repeat until wounded or dead. The German commanders on Cree never understood what happened to their snipers.

Afteraction reports noted unexplained losses among Falam Jagger sniper teams during the final week of the campaign. Several reports mentioned finding dead snipers with no evidence of how they had been killed. No artillery strikes, no air attacks, just single rifle shots from close range. One German intelligence assessment speculated that Allied forces had deployed specialized counter sniper units equipped with silenced weapons.

Another report suggested partisan activity by civilians. Nobody guessed the truth. One New Zealand sergeant in a stolen uniform. The deception remained classified for years after the war. British and New Zealand military authorities did not want to publicize tactics that violated international law, even if those tactics had been effective.

Hume’s Victoria Cross citation mentioned his sniper kills, but omitted any reference to the German camouflage smock or the deception methods he employed. The full story only emerged gradually as veterans gave interviews and military historians accessed declassified records. By then, Hume was decades removed from the war and had no interest in discussing details.

When pressed, he gave the same answer every time. He saw German equipment that could help him kill German snipers. He took it. He used it. That was all. But the simplicity of that answer obscured the deeper question. What kind of man could do what Hume did? What psychological makeup allowed someone to walk calmly toward enemy soldiers while wearing their uniform, knowing that discovery meant immediate execution? Most soldiers could not have maintained that deception for 5 minutes.

Hume maintained it for 8 days. The answer seemed to be grief and rage channeled into absolute focus. His brother died on May 26th. Hume killed 19 snipers in the following two days. The timing was not coincidental. Something fundamental changed after he received that message about Harold. The tactical calculations remained the same, but the emotional context shifted. This was no longer just about saving Allied lives.

This was about making the Germans pay. That motivation probably kept him alive. Soldiers fighting for abstract principles sometimes hesitated at critical moments. Soldiers fighting for personal reasons rarely did. When Hume walked toward those five German snipers on the hillside and opened fire at 40 yards, he was not thinking about military doctrine or tactical advantage.

He was thinking about his brother lying dead somewhere on the same island. And then he went back out and killed more Germans. If this story moved you the way it moved us, do me a favor. Hit that like button. Every single like tells YouTube to show this story to more people. Hit subscribe and turn on notifications.

We’re rescuing forgotten stories from dusty archives every single day. Stories about sergeants who saved lives with stolen rifles and deception. Real people, real heroism. Drop a comment right now and tell us where you’re watching from. Are you watching from the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, Australia? Our community stretches across the entire world. You’re not just a viewer. You’re part of keeping these memories alive.

Tell us your location. Tell us if someone in your family served. Just let us know you’re here. Thank you for watching. And thank you for making sure Clive Hume doesn’t disappear into silence. These men deserve to be remembered, and you’re helping make that

News

CH2 Why Patton Wanted to Attack the Soviets in 1945 – The Warning Eisenhower Refused to Hear

Why Patton Wanted to Attack the Soviets in 1945 – The Warning Eisenhower Refused to Hear On the gray,…

CH2 How Did Hitler Fund a Huge Military When Germany Was Broke?

How Did Hitler Fund a Huge Military When Germany Was Broke? Germany, 1923. The winter air was sharp and cold,…

CH2 How One Woman Used a 0.16-Second Echo to Collapse a 4,200-Man Japanese Tunnel Fortress

How One Woman Used a 0.16-Second Echo to Collapse a 4,200-Man Japanese Tunnel Fortress At 6:42 a.m. on June 26,…

He Mocked Me for Approaching the VIP Lift—Then It Revealed My Classified Identity…

He Mocked Me for Approaching the VIP Lift—Then It Revealed My Classified Identity… The air in the lower levels of the…

He Mocked Me on Our Date for Being a Civilian—Then Found Out I Outranked Him

He Mocked Me on Our Date for Being a Civilian—Then Found Out I Outranked Him The pressure on my…

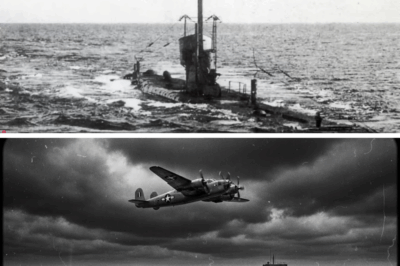

CH2 German Submariners Encountered Sonobuoys — Then Realized Americans Could Hear U-Boats 20 Miles Away

German Submariners Encountered Sonobuoys — Then Realized Americans Could Hear U-Boats 20 Miles Away June 23rd, 1944. The North…

End of content

No more pages to load