The Unbelievable Survival of Lieutenant Robert S. Johnson – How One P-47 Thunderbolt Defied 200 Bullets and Forced a German Ace to Kneel

The summer sun hung low over northern France on June 26th, 1943, as Lieutenant Robert S. Johnson climbed into the cockpit of his Republic P-47 Thunderbolt. The aircraft, nicknamed Halfpint, was sleek, heavy, and bristling with firepower, a jug-shaped behemoth of metal and promise. At twenty-three, Johnson had flown thirteen combat missions, claimed only a single aerial victory, and today, like all missions, felt like stepping into a storm waiting to break.

He checked his instruments one last time, glanced at the squadron lined up on the tarmac at RAF Manston, and heard the engines roar to life. Forty-eight Thunderbolts lifted off into the fading daylight, escorting B-17 Flying Fortresses returning from a raid on Villaubé Airfield near Paris. The mission briefing had promised light opposition. Intelligence had promised safe passage. Neither was true.

At 27,000 feet near Forge Leo, the sky erupted. Sixteen Focke-Wulf FW190s from II./JG26 dove from the clouds, guns blazing, filling the air with the thunder of German cannon fire. Johnson, in tailing position of the 61st Fighter Squadron, immediately felt the shudder of impact. His canopy exploded into fragments, and a spray of hydraulic fluid coated his face. A shell tore through his fuselage, another shredded the tail. Every pilot knows the “coffin corner” by instinct; Johnson was trapped there.

Metal screamed. Sparks flew. Oil coated the windscreen, mingling with sweat and blood. A cannon shell punched the armor behind his head, bending the canopy frame. Fire erupted inside the cockpit. The P-47 went into a flat spin. Johnson fought the controls with every ounce of strength he had, jerking the rudder, pulling the stick, fighting physics as much as the aircraft. The engine coughed but kept running. Somehow, against every rule of the sky, the jug held together.

Alone. That was the first realization that struck him. His wingman, the shield every pilot counted on, was gone. Scattered formations meant survival depended entirely on Johnson’s skill, the resilience of his aircraft, and sheer luck. He pointed the battered P-47 toward the English Channel, praying the Pratt & Whitney R-2800 radial engine would hold.

From the mirror mounted above his instrument panel, he saw a blue-and-yellow FW190 closing. Major Egon Mayer, an ace with 102 confirmed kills, had singled him out. Johnson braced for the inevitable. The German pilot opened fire, machine guns rattling, cannon shells spent. The armor plate behind Johnson’s head rang like a bell with each impact. Yet Halfpint shuddered and stayed aloft.

Johnson fought desperately to evade, yawing the P-47, slowing to stall speed, jerking the throttle. Bullets tore through wings and fuselage. Fuel streamed behind in ribbons, self-sealing tanks just holding together. Mayer, now in close formation, scanned the wrecked American fighter, counted holes, measured damage. The FW190 banked, saluted—a gesture unheard of in the heat of combat. Johnson, oil-covered and bleeding, hardly dared to breathe.

Five miles to the coast, the Channel stretched ahead like a thin thread of hope. He fought the controls as the damaged P-47 listed, shuddered, and groaned with every gust. Landing gear was impossible; hydraulics destroyed. Only one chance remained: a belly landing on the tiny strip at RAF Manston.

Continue below

At 6:47 p.m. on June 26th, 1943, Lieutenant Robert S. Johnson felt his Republic P47 Thunderbolt shudder as 20 millimeter cannon shells tore through the fuselage over northern France, watching his canopy explode into fragments while hydraulic fluid sprayed across his face and 16 Faul FW190 fighters swarmed around him.

23 years old, 13 combat missions, one aerial victory. The German pilots had already shot down four other P-47s from the 56th Fighter Group that afternoon. Three more American pilots were dead in the English Channel. Johnson squadron had launched from RAF Manston at 1700 hours to escort B7 flying fortresses returning from Villaubé airfield near Paris.

48 Thunderbolts crossed the channel in tight formation. The mission briefing promised light opposition. Intelligence was wrong. Near Forge Leo, the FW190s from second group JG26 dropped from the clouds at 27,000 ft. Johnson was flying tailin position in the 61st Fighter Squadron, the worst place to be. German pilots called it the coffin corner.

The first burst hit Johnson’s aircraft before he could transmit a warning. 21 20 mm cannon shells ripped through Halfp Pine’s fuselage. The hydraulic system ruptured. Hot oil covered the windscreen. A machine gun bullet grazed the tip of his nose. Shrapnel from a cannon shell buried itself in his right leg.

Another shell punched through the armor plate behind his head and jammed the canopy frame. Fire erupted in the cockpit. The P47 went into a flat spin. Johnson kicked left rudder and pulled back on the control stick. The aircraft’s nose came up. The spin stopped. Somehow the engine fire went out, but Johnson couldn’t see. Hydraulic fluid had turned his goggles opaque. He ripped them off. Oil covered his face. He tasted metal and fuel.

He reached up and pulled the canopy release. Nothing happened. He braced his boots against the instrument panel and pulled with both hands. The frame was bent. The canopy wouldn’t move. He was trapped inside a crippled fighter 30 mi from the English coast with enemy aircraft circling. The 56th Fighter Group had lost 47 pilots in the first 3 months of operations over Europe.

Most died in their first 10 missions. Johnson had beaten those odds by following one rule. Stay with your wingman. Never fly alone. But his wingman was gone. The formation was scattered. Every P47 was fighting for survival or already spinning toward the Earth. Johnson pointed halfpint toward the channel and pushed the throttle forward.

The Pratt and Whitney R2800 radial engine coughed but kept running. Maximum continuous power, 2,300 horsepower. The big fighter accelerated to 280 mph despite the damage. Republic Aviation had built the P47 around one principle, bring the pilot home. The aircraft weighed 7 tons empty, nearly 8 tons with fuel and ammunition.

Some pilots called it the jug because its profile looked like a milk bottle. Others called it the flying bathtub. But every pilot who flew it trusted one thing. The Thunderbolt could take punishment. Johnson had seen P47s return with cylinders shot away from their radial engines.

He’d seen aircraft land with three-foot holes in their wings, but he’d never seen damage like this. Cannon shells had blown holes through both wings. The tail section looked like someone had attacked it with an axe. Half the instrument panel was destroyed. The oxygen system was dead. Without oxygen at altitude, he had maybe 10 minutes before hypoxia shut down his brain.

If you want to see how Johnson survived what happened next, please hit that like button. It helps us share these forgotten stories with more people. And please subscribe. Back to Johnson. He dropped to 15,000 ft where he could breathe. The channel was 15 mi ahead.

If he could reach the coast, the RAF airc rescue launches might pick him up if his engine kept running. If the Germans didn’t finish him off first. Johnson glanced in his mirror. A blue and yellow folk wolf FW190 was closing from his six o’clock position. Single aircraft alone. The German pilot was an experienced ace. Major Egon Meyer 102 victories.

The man who developed the head-on attack against American bomber formations. He pulled into firing position 50 yards behind the crippled Thunderbolt. Johnson hunched down behind the armor plate and waited for the cannon shells that would end it. Mayor opened fire at 45 yds. 7.92 mm machine gun rounds hammered into the Thunderbolts fuselage. The 20 mm cannons were empty.

Mayor had expended all his cannon ammunition attacking the B7 formation earlier, but two MG17 machine guns still had plenty of bullets, 600 rounds per minute, each gun. Johnson felt the impacts through his seat, metal tearing, rivets popping. The armor plate behind his head rang like a bell with each hit. He kicked the rudder pedals left and right.

The P47 yawed back and forth. Not evasive maneuvers, just desperation, making himself harder to hit. He pulled back on the throttle to slow the aircraft. 190 mph, just above stall speed. The FW190 shot past him. Mayor had misjudged the closing speed. Johnson squeezed his trigger. His six 50 caliber machine guns were still operational.

Tracers arked toward the German fighter. All of them missed. Johnson’s oil-covered windscreen made accurate shooting impossible. He could barely see the gun sight, but he wanted Mayor to know he wasn’t giving up. Mayor banked left and climbed, setting up for another pass. Johnson pushed the throttle forward again. The R2800 responded.

The big radial engine had taken multiple hits but kept running. 18 cylinders arranged in two rows, air cooled. No vulnerable coolant system to rupture. German fighters with liquid cooled engines died from a single hit to their radiators. The P47 just kept flying. Johnson checked his fuel gauge.

The needle showed half full, but he didn’t trust it. Cannon shells had damaged the fuel system. He might have less than 30 minutes of flight time remaining. The English coast was still 12 mi away. He was losing altitude, 14,000 ft. The aircraft was handling like a truck with flat tires. Mayor came in from the right quarter, lower this time, matching Johnson’s speed.

The FW190 was faster than the Thunderbolt in level flight, 390 mph versus 330. But Mayor wasn’t trying to run away. He was executing a textbook fighter attack, closing to point blank range, making every bullet count. The second burst lasted 8 seconds. Machine gun fire rad the P47 from nose to tail. Bullets punched through the engine cowling, shredded the right wing, blew holes in the tail assembly.

One round hit the main spar in the left wing. Another severed a control cable. The aircraft shuddered and rolled slightly to the right. Johnson fought the controls. The P-47 leveled out. He glanced at the wing. Three-foot holes. He could see through the aluminum skin to the internal structure. Fuel was streaming from a ruptured tank, not spraying, just trailing behind like a ribbon.

That meant the self-sealing bladders were doing their job. The rubber layers inside the fuel tanks were closing around the bullet holes slowly. Not fast enough to stop all the leaks, but fast enough to prevent an explosion. Mayor pulled alongside 50 feet away. Close enough for Johnson to see his face. The German was looking at the Thunderbolt, examining the damage.

Johnson saw him shake his head. The P47 should have been falling out of the sky. By every rule of aerial combat, Johnson should be dead. The aircraft had absorbed more punishment than any fighter Mayor had ever seen. The FW190 dropped back. Johnson watched in his mirror. Mayor was lining up for a third pass.

This time from directly behind, 6:00 low, the killing position. Johnson had no moves left. The aircraft was too damaged to maneuver. His visibility was too poor to return effective fire. His hydraulics were gone. His controls were barely responding. He was flying on borrowed time in an airplane that should have been a funeral p. The channel was 10 mi ahead.

Johnson could see the coastline, white cliffs, England, safety, if he could survive the next 30 seconds, if Mayor’s guns jammed. If the P47’s engine kept running, if the fuel lasted. Too many ifs. Mayor opened fire for the third time. The machine guns hammered Johnson’s aircraft for another 6 seconds. The tail section took most of the hits.

Rudder, elevators, vertical stabilizer, all shredded. The P47 wallowed in the air like a wounded bird. Johnson held the stick with both hands, fighting to keep the nose up, fighting to keep flying. Then silence. The firing stopped. Johnson waited for the fourth pass, for the burst that would finally tear the Thunderbolt apart for the end.

But Mayor didn’t attack again. The FW190 pulled alongside once more, even closer this time, 30 ft. Johnson could see Mayor clearly now through the oil smeared canopy. The German ace looked at Johnson, then at the battered Thunderbolt. His wingman had peeled off minutes earlier, low on fuel, heading back to base.

Mayor was alone over the channel, deep in enemy airspace. His fuel gauge was dropping. Every minute he stayed increased his risk of being caught by RAF Spitfires on patrol. But Mayor didn’t leave. He flew formation with Johnson, examining the American fighter, counting the holes, the shredded wings, the destroyed tail section, the smoking engine, the oil streaming from a dozen ruptures.

He’d fired over 300 machine gun rounds into this aircraft at pointblank range after other German pilots had already hit it with 21 cannon shells. The P47 was still flying. Mayor raised his hand, a salute, slow and deliberate, pilot to pilot. Then he rocked his wings twice. The universal signal, acknowledgement, respect.

The FW190 banked hard right and dove away toward France. Mayor was out of ammunition, out of time, and apparently out of interest in killing a man this stubborn. Johnson watched the blue and yellow fighter disappear into the haze over Normandy. His hands were shaking, not from fear, from exhaustion. His face was covered in oil and blood. His right leg throbbed where shrapnel had torn through his flight suit.

He’d been holding the control stick in a death grip for 15 minutes. His fingers were cramping. The English coast was 5 mi ahead. Johnson checked his altimeter, 9,000 ft, still losing altitude. The P47 was descending at 200 ft per minute. He did the math. At this rate, he’d reached the channel at 3,000 ft, maybe lower. The question was whether he’d reached land before he ran out of sky.

The fuel gauge showed one quarter tank, probably less in reality. The gauge had been unreliable since the attack. Johnson calculated his remaining flight time, 20 minutes, maybe 25. Manston was 35 mi inland from the coast. Too far. He needed a closer airfield. any airfield, any flat piece of ground long enough to belly land a 7-tonon fighter.

White cliffs appeared through the oil smeared windscreen. Do the narrowest point of the channel. Johnson had crossed here dozens of times, always in formation, always with his squadron, never alone, never in an aircraft this damaged. He crossed the coastline at 7,000 ft, English soil. He’d made it, but he wasn’t safe yet. The landing gear indicator showed red. Hydraulics dead.

No way to lower the wheels. Johnson tried the emergency hand pump. The handle moved, but nothing happened. The system was too badly damaged. He’d have to belly land. No gear, no flaps. Just slide the Thunderbolt onto the runway on its belly and hope the fuel tanks didn’t explode on impact.

RAF Manson appeared ahead. The forward operating base where his mission had started 90 minutes earlier. The field was small, barely long enough for a normal landing. For a wheels up crash landing with an overweight fighter, it would be marginal. But Johnson had no choice. His fuel was nearly gone. The engine was making new sounds, grinding, knocking metal on metal. The R2800 was dying.

He circled the field once, burning his remaining altitude. Air traffic control fired red flares. Emergency landing. Clear the runway. Ambulance and fire trucks rolled toward the approach end. Ground crews stopped what they were doing and watched. They’d seen damaged aircraft before, but nothing like this.

Johnson lined up on final approach. 2,000 ft. Air speed 140 mph. Too fast. But without flaps, he couldn’t slow down more without stalling. The P47 had a reputation for being difficult to land, even in perfect conditions. With no hydraulics, no landing gear, and half the control surfaces shot away, it would be nearly impossible. 1,000 ft.

He pushed the nose down slightly. The runway filled his windscreen. 500 ft. The engine coughed, sputtered. Johnson held his breath. The R2800 caught again, kept running. 300 ft. He could see individual people on the ground. Fire crews, medics, officers, all staring up at halfpint 100 ft. Johnson pulled back on the stick. The nose came up, flaring for landing. The P47 settled toward the concrete.

He cut the mixture. The engine died. Sudden silence except for the wind howling through the bullet holes. The Thunderbolts belly hit the runway at 120 mph. Sparks erupted as metal scraped concrete. The sound was deafening like a train derailing. The P47 slid down the runway, trailing smoke and flame. Johnson gripped the control stick, trying to keep the wings level.

The aircraft wanted to ground loop to spin sideways and cartwheel. He fought it with rudder and aileron. The nose stayed straight. 200 yd. The P47 was decelerating, friction doing its job. 300 y the speed dropped below 80 mph 400 y 60 mph 500 yd the thunderbolt shuttered to a stop 50 ft from the end of the runway the propeller blades were bent backward the belly was torn open but the fuel tanks hadn’t exploded Johnson was alive tried to open the canopy still jammed pushed harder nothing moved was filling the cockpit not from fire from hot metal and burned rubber. But Johnson could smell aviation

fuel fumes. The belly tanks had ruptured in the landing. Fuel was pooling under the aircraft. One spark and the whole thing would ignite. Fire crews arrived within seconds. A firefighter climbed onto the wing with a crowbar. He jammed it into the canopy frame and levered. The plexiglass cracked. The frame bent. The canopy moved 6 in. enough.

Two more firefighters grabbed Johnson under his arms and pulled him out. They carried him away from the aircraft 50 yards, then 100. Then they laid him on the grass. A medic cut away Johnson’s flight suit. Blood soaked the right leg. Shrapna wound, not arterial, painful, but survivable. Burns on his face and hands.

First degree, maybe second degree in places. The medic cleaned the oil from Johnson’s eyes with sterile water. Johnson blinked. His vision cleared slightly. Everything was blurry, but he could see. An ambulance arrived. Medics loaded Johnson onto a stretcher. He refused, pushed himself up, walked to the ambulance on his own. His right leg barely supported his weight, but he walked.

A pilot from the 61st Fighter Squadron saw him and started to say something. Johnson waved him off. No words. Not yet. He climbed into the ambulance and sat down. Only then did he start shaking. The medical officer at Manston treated Johnson’s wounds, cleaned and bandaged the shrapnel injury, applied burn ointment to his face and hands, gave him morphine for the pain. But Johnson refused to stay in the medical tent. He wanted to see his aircraft. The doctor argued.

Johnson ignored him. He limped back toward the runway. Halfpint was surrounded by mechanics and pilots. 20 men, maybe 30, all staring at the wreckage. The chief mechanic was walking around the aircraft with a clipboard, counting damage, writing notes. He looked up when Johnson approached. His expression was unreadable.

Johnson stood at the wing and started counting bullet holes himself. The right wing, five holes, 10 holes, 20 holes. He lost count at 37 and moved to the fuselage. More holes everywhere. The tail section was shredded. The rudder looked like Swiss cheese. The elevators had holes big enough to put a fist through. He walked to the left wing. More of the same.

Holes, tears, shredded metal. The chief mechanic walked over, handed Johnson the clipboard. The tally was written in neat columns. 21 20 mm cannon shell impacts. Over 200 machine gun bullet holes. The mechanic had stopped counting at 208, and he’d only examined one side of the aircraft. The other side probably had just as many.

Johnson looked at the numbers. 208 confirmed holes, probably over 400 total, 400 hits, and he was alive. The chief mechanic pointed to the armor plate behind the pilot seat. It was cratered and dented from repeated impacts. At least 15 machine gun rounds had hit that plate. Every one of them would have killed Johnson if not for that 1-in steel protection. The engine cowling was destroyed.

Multiple cylinders had been hit, but the R2800 had kept running. The fuel tanks showed evidence of self-sealing. The rubber bladders had closed around dozens of punctures, slowly leaking, but not exploding. The tail section should have separated in flight. It hadn’t. The control cables were severed in multiple places. Somehow, enough redundancy remained for Johnson to maintain control.

Republic Aviation had designed the P47 to survive, but even they hadn’t imagined this level of damage. This was beyond engineering specifications, beyond testing parameters, beyond anything any pilot had experienced and lived to report. Halfpint was a flying wreck that refused to crash. The mechanic made his recommendation. Category E, total loss, scrap.

The airframe was too damaged to repair, but the engine might be salvageable. Some parts could be recovered. The rest would go to the scrap heap. Halfpine had flown its last mission. Johnson touched the fuselage. Cold metal, rough where bullets had torn through. This aircraft had saved his life.

The German pilot had saluted, but it was this machine that deserved the honor. Seven tons of aluminum and steel that refused to die. He turned away. His squadron mates were waiting, questions in their eyes. How did you survive? What happened up there? Who was the German pilot? Johnson didn’t have answers. Not yet. Not while his hands were still shaking. The 56th Fighter Group lost five pilots on June 26th.

Four were shot down over France. Lieutenant Samuel Hamilton bailed out over the English Channel when his landing gear failed. RAF Air Rescue found him 2 hours later north of Yarmouth, hypothermic, but alive. The other four never came home. Lieutenant Gerald Johnson, no relation to Robert, claimed he’d shot down one of the FW190s chasing Robert’s aircraft.

He never mentioned it to Robert, didn’t want to diminish the story. Years later, he wrote about it in his memoir. By then, it didn’t matter. The legend was already established. Robert Johnson versus the German ace. David versus Goliath. The pilot who refused to die. Johnson spent three days in the hospital at Manston. Burns treated, shrapnel removed from his leg, rest and observation for shock.

The flight surgeon recommended 2 weeks of medical leave. Johnson requested 5 days. They compromised on one week. On July 3rd, he reported back to the 61st Fighter Squadron at Hailsworth, ready to fly. His squadron commander took one look at his bandaged face and grounded him for another week.

July 10th, Johnson climbed into a new P47D, serial number 428461. He named it Lucky. Not ironic, not a joke. Lucky was exactly what he’d been on June 26th. Lucky the canopy jammed and prevented him from bailing out over France, where he’d have been captured. Lucky the engine kept running despite multiple hits. Lucky mayor ran out of ammunition.

Lucky, the P-47 was built like a tank. His first mission after the incident was a bomber escort to the Netherlands. Uneventful, no enemy contact. Johnson flew tight formation, watched his 6:00 constantly. Every shadow in the clouds looked like an FW190. Every distant speck might be an enemy fighter. The fear wasn’t gone. It had just changed shape.

He’d looked death in the face for 15 minutes on June 26th. The memory didn’t fade, but the fear made him sharper, more cautious, better. He stopped taking risks, stopped chasing kills. His job was bomber escort, protection, not glory. Colonel Hubert Zki, commander of the 56th Fighter Group, noticed the change.

The old Johnson had been aggressive, sometimes reckless. The new Johnson was patient, tactical. He used the P-47 strengths, high-speed dives, zoom climbs, energy fighting, never turning with German fighters, never getting slow. August 13th, Johnson shot down his second FW190 northwest of Eprris. Clean kill, no damage to his aircraft. He returned to base and reported the victory without celebration.

One more tally mark, nothing special. September brought two more victories. October 8th was different. Johnson and his wingman became separated during a mission to Bremen. Alone again. But this time, Johnson wasn’t helpless. He spotted a Messormid BF-110 attacking a B17. Johnson dove from altitude. 6,000 ft of airspeed advantage. The BF-110 never saw him coming.

Johnson fired a 2-cond burst. The German aircraft exploded. His fourth victory. As he pulled up from the dive, he saw four FW190s below, attacking more bombers. Johnson rolled inverted and dove again, upside down, firing while pushing forward on the stick to track the target. Unorthodox, effective. He shot down one FW190, then a second.

October 10th, another mission to Müster. Heavy fighter opposition. Johnson’s squadron engaged an estimated 40 German aircraft. A massive dog fight. Johnson destroyed one BF-110 and one FW190, but his aircraft took severe damage. Again, not as bad as June, but bad enough. Both he and Major David Schilling became aces that day.

Fifth and sixth kills, five or more aerial victories, the threshold that separated ordinary fighter pilots from legends. Johnson had become an ace while flying primarily as a wingman, protecting other pilots, following orders, not hunting kills. Hugh Zempi promoted him to flight leader on November 26th. Johnson’s first mission in that role lasted 10 minutes. Fuel leak forced him to abort after takeoff. Embarrassing.

But the leak wasn’t his fault. Mechanical failure. He flew as flight leader the next day, led four aircraft on a sweep over Belgium. No enemy contact, but no mistakes either. December 22nd, Johnson shot down two FW190s. December 29th, one more. January 5th, 1944, two victories. January 29th, another. His tally was climbing.

13 confirmed kills by early February. He was becoming one of the top scorers in the Eighth Air Force. But he never forgot June 26th. never forgot how close he’d come to being another name on the casualty list. Every mission started with the same ritual.

Walk around the aircraft, check the armor plate behind the seat, test the canopy, make sure it could open, check the fuel system, check the controls, trust nothing, verify everything. The mechanics thought he was paranoid. Maybe he was, but paranoid pilots came home. Careless pilots died. March brought six more victories. Johnson’s total reached 19, second highest in the 56 fighter group behind only Francis Gabreski who had 22.

The two of them were racing toward Eddie Rickenbacher’s World War I record of 26 aerial victories. No American pilot in Europe had surpassed that number. Not yet. April 1944, Johnson shot down three German fighters in one mission. His total reached 22, four short of Rickenbacher’s record. Gabreski was at 24. Two short. The race was tightening. But Johnson wasn’t competing with Gabreski. He was competing with himself. Every mission was a test.

Could he stay alive one more day? Could he bring his wingmen home? Could he protect the bombers? The kills were secondary. May 8th, a mission to Brunswick. Johnson spotted a formation of FW190s attacking B17s at 18,000 ft. He dove with his flight. Four P47s against 12 German fighters. Bad odds, but the bombers needed help. Johnson picked the nearest FW190 and fired.

Deflection shot, 45° angle, 2C burst. The German aircraft rolled over and fell away, trailing smoke. Victory number 23. Seconds later, another FW190 crossed his nose. Johnson didn’t think. Pure instinct. He pulled lead and fired. 1 second burst. 50 caliber rounds walked across the German fighter’s fuselage. The engine exploded.

The pilot bailed out. 24 victories, two short of the record. Johnson stayed in the fight. His flight scattered. Each P47 engaged individually. No formation, just chaos. Johnson tracked another FW190. This one was experienced. The German pilot saw Johnson coming and broke hard left. Johnson followed. The FW190 was more maneuverable, but Johnson had altitude energy. He didn’t try to turn with the German.

He extended, climbed, reset the engagement, then dove again. The FW190 pilot made a mistake. He pulled up to meet Johnson headon. Mutual pass, both aircraft firing. Johnson held his trigger down. 3 seconds. The Germans canopy shattered. The aircraft snap rolled right and dove. Out of control. Johnson pulled up hard. 6 G’s. His vision tunnled. Gray edges.

He eased back on the stick. Vision cleared. The FW190 was spinning toward the ground. No parachute. 25 victories. One short of Rickenbacher’s record. Johnson checked his fuel. Low. Ammunition almost empty. He called his flight, formed up what was left. Two P-47s. The other two had broken off earlier. Low fuel or damage.

Johnson led the pair back toward England. No celebration, no excitement, just exhaustion. Three kills in 12 minutes. His hands were shaking again, like June 26th, but this time from adrenaline, not fear. He landed at Hailworth at 1400 hours. Debriefing took an hour. Three confirmed victories. Gun camera footage reviewed. Witnesses verified. The intelligence officer made the announcement. Lieutenant Robert S.

Johnson, 25 aerial victories, one short of Eddie Rickenbacher, tied with Francis Gabreski, the highest scoring American pilots in the European theater. Gabreski shot down two German fighters three days later. 26 victories. He tied Rickenbacher’s record. Now Johnson was behind 25 versus 26.

The squadron was buzzing. Who would break the record first, Johnson or Gabeski? The press was interested. War correspondents showed up at Hailworth asking questions, taking photographs, writing articles about the two aces. Johnson ignored the attention. He focused on the missions. May was brutal. The eighth air force was pushing deep into Germany.

Berlin, Munich, targets that brought up everything the Luftwaffa had left. Experienced pilots, new aircraft, improved tactics. The easy victories were over. Every kill was earned. May 15th, Johnson damaged two FW190s. Probably destroyed, but not confirmed. No witnesses. Gun camera footage inconclusive. They counted as probables, not kills. Frustrating, but fair.

The rules were strict. 5-second burst minimum on camera. Target must show visible damage, fire, explosion, pieces falling off, or a witness from another aircraft must verify. May 24th, another mission, another dog fight. Johnson shot down one BF 109. 26 victories, tied with Gabreski, tied with Rickenbacher.

The next kill would break the record. Make history. Johnson didn’t think about it. Thinking got pilots killed. He flew his missions, protected bombers, brought his flight home. That was the job. Hub. Zimi extended Johnson’s combat tour. Standard rotation was 200 combat hours. Johnson had logged 197, but Zim needed his best pilots.

Germany was throwing everything into defending the homeland. Experienced fighter pilots were worth more than fresh replacements. Johnson didn’t argue. Three more hours wouldn’t kill him, probably. May 27th, Johnson led eight P47s on a sweep over France. They encountered a formation of FW190s near Re. 12 German fighters. Johnson’s flight had altitude advantage. They dove.

The Germans scattered. Johnson locked onto one FW190, chased it down through 8,000 ft. The German pilot was good. He jinked, barrel rolled, split s, everything. But Johnson stayed with him, patient, waiting for the mistake. The FW190 pulled too hard in a turn, stalled, nose dropped. Johnson was there. 1 second burst. The German aircraft exploded. 27 victories.

Robert S. Johnson had broken Eddie Rickenbacher’s World War I record, first American pilot in Europe to do it. The news reached Hailworth before Johnson landed. The ground crews were waiting when Johnson taxied to his hardand. They’d heard the radio traffic. 27 victories, a new American record. Mechanics and armorers surrounded Lucky before the propeller stopped spinning.

Someone had painted another kill marking on the fuselage, a small swastika, the 27th in a row along the left side of the cockpit. Johnson climbed out of the cockpit. No celebration, no speeches. He walked to the debriefing room alone, filled out the combat report, gun camera footage, witness statements, time, location, target identification.

The intelligence officer reviewed everything and stamped the form. confirmed official. 27 aerial victories, more than any other American pilot in Europe. Hubzki called Johnson into his office that evening. Promotion to captain effective immediately. Orders to return to the United States. War bond tour. Public appearances. The military needed heroes for morale.

Johnson had become exactly that. the quiet pilot from Oklahoma who’d survived 200 bullet holes, who’d broken Rickenbacher’s record, who’d proven the P47 could fight and win against the best the Luftvafa had. Johnson flew his final combat mission on May 8th, 1944. 91 total missions, more than any other pilot in the 56th Fighter Group at that time.

203 combat hours, 27 confirmed victories, two probable kills, four damaged. He’d flown three different P-47s during his tour. Halfpint, Lucky, and a third aircraft he’d named All Hell after his squadron’s radio call sign. The statistics didn’t capture everything. the near-death experience on June 26th, the burns, the shrapnel wound, the nightmares that followed, the weight of command as flight leader, the responsibility of bringing younger pilots home, the friends who didn’t make it, the empty chairs at briefings, the names that accumulated on the casualty

list. Johnson left England on June 6th, 1944. D-Day, the largest amphibious invasion in history. Thousands of Allied soldiers landing on French beaches while Johnson sailed west across the Atlantic. The timing was coincidental but symbolic. The war in Europe was entering its final phase. The tide had turned.

American fighter pilots like Johnson had helped turn it. He arrived in New York on June 12th. Met his wife Barbara. First time he’d seen her in 18 months. She barely recognized him. He lost 20 lb. His face showed burn scars. His right leg still bothered him where the shrapnel had hit, but he was alive, home, safe.

The War Department sent Johnson on a publicity tour, bond rallies, factory visits, radio interviews. He spoke to workers at Republic Aviation in Farmingdale, New York, the same factory that had built the P47. He thanked them, told them their aircraft had saved his life, saved hundreds of lives.

The P-47 wasn’t the prettiest fighter, wasn’t the fastest, but it was the toughest, and toughness won wars. Johnson visited hospitals, talked to wounded soldiers, pilots who’d been shot down, burned, injured. Some had flown P-47s. They asked about combat, about tactics, about survival. Johnson told them the same thing Hubzimi had taught him. Stay with your wingmen. Use your advantages. Never dogfight.

The P47 was built to dive and zoom, not turn and burn. He spoke at high schools, told students about service, sacrifice. The kids wanted to hear about dog fights, aerial combat, killing Germans. Johnson talked about teamwork instead, about the mechanics who kept the aircraft flying, the armorers who loaded the guns, the radio operators who guided them home, the rescue crews who pulled pilots from the channel. Combat was a team effort.

Heroes didn’t win wars. teams did. Francis Gabreski passed Johnson’s record on July 5th. 28 victories, then 29, then 30. He became the highest scoring American ace in Europe. Johnson sent him a congratulatory telegram. No jealousy, no rivalry, just respect.

Gabreski was shot down on July 20th while strafing a German airfield. Captured, spent the rest of the war in a P camp. He survived, came home, later flew in Korea, retired as a colonel. They remained friends for life. David Schilling eventually reached 22 and a half victories. Gerald Johnson reached 16. The 56th fighter group as a whole was credited with destroying over 674 German aircraft in the air, plus 311 on the ground, nearly 1,000 total. the highest scoring fighter group in the eighth air force, Zimkey’s Wolfpack.

They’d earned the name. Robert Johnson never flew combat again after May 1944. The Army Air Forcees promoted him to major, assigned him to training duties. He taught new pilots, passed on the lessons he learned, survival tactics, energy fighting, situational awareness. Some of those students went to Europe, flew P47s, came home alive.

Johnson considered that his greatest achievement. Not the 27 victories, the pilots he helped survive. The war in Europe ended May 8th, 1945. VE Day, victory in Europe. Johnson was in Oklahoma. Civilian life, but the images stayed with him. June 26th, 1943. The moment Egon Mayor saluted and flew away.

The moment the P47 refused to crash. Johnson returned to active duty in 1946. The Army Air Forces became the United States Air Force in 1947. Johnson stayed through the transition, but he never flew combat again. Staff positions, training commands, administrative roles. He retired from the Air Force Reserve in 1965 as a lieutenant colonel.

24 years of service, only 14 months in combat. But those 14 months defined everything. He received the Distinguished Service Cross, second highest military decoration for valor. Citation read, “Extraordinary heroism in aerial combat, the Silver Star, Distinguished Flying Cross with eight oakleaf clusters, air medal with nine oakleaf clusters, purple heart for the wounds he sustained on June 26th.

The medals filled a shadow box. He kept it in a closet, rarely showed anyone.” Johnson worked in the aerospace industry after retirement, Republic Aviation, the same company that built the P47. He consulted on fighter design, attended air shows, spoke to aviation clubs, but mostly he lived quietly.

Tulsa, Oklahoma, where he’d started, where he’d learned to fly, where he belonged. The story of June 26 followed him everywhere. Reporters asked about it. Historians researched it. Aviation enthusiasts debated it. Some claimed the German pilot was Egon Mayer, the ace with 102 victories who died in 1944. Others argued Mayor wasn’t even in the area that day, that German record showed no claims from JG2, that it was probably another pilot from JG26.

The identity remains debated, but what’s certain is this. A German fighter ace with an FW190 emptied his guns into Johnson’s P47, saluted and left. That part was real, documented, witnessed. Johnson wrote a memoir in 1958, Thunderbolt, co-authored with Martin Kaden. The book became a classic of aviation literature. It described combat in the P47 with brutal honesty.

the fear, the exhaustion, the friends who died, the moral weight of killing, the randomness of survival. Johnson didn’t glorify war. He described it as it was necessary, terrible, something to be endured and ended. The Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum in Washington displayed a P47D Thunderbolt, not Johnson’s aircraft.

Halfpint had been scrapped in 1943, but the museum’s P47 represented all of them. The seven-tonon fighters that brought pilots home. Johnson visited the museum several times stood next to the aircraft touched the metal remembered. The mighty eighth Air Force Museum in Savannah, Georgia opened in 1996.

It honored the bomber crews and fighter pilots who fought over Europe. Johnson attended the dedication, met other veterans, pilots he hadn’t seen in 50 years. They were old men now, gray hair, slow movements, but they remembered the missions, the fear, the friends who never came home. They remembered everything.

Johnson died on December 27th, 1998. Tulsa, Oklahoma, 78 years old. He’d outlived most of his squadron. Outlived Hubzki. Outlived Gabby Gabeski. He was buried at River Hills Community Church Cemetery in Lake Wy, South Carolina. Full military honors. Three F-16 Fighting Falcons flew missing man formation overhead, 21 gun salute, taps, the ceremonies for heroes.

His legacy wasn’t just the 27 victories. It was what he represented. The ordinary American who did extraordinary things when required. The pilot who followed orders, protected bombers, brought his wingman home, who survived when survival seemed impossible, who earned respect from his enemy through sheer refusal to die.

The P-47 Thunderbolt flew in every theater of World War II. Europe, Pacific, Mediterranean, China, Burma, India. It destroyed more ground targets than any other American fighter. Thousands of locomotives, tanks, trucks, bridges. But pilots loved it for one reason. It brought them home. Even when shot full of holes. Even when it should have crashed, the P47 kept flying.

If this story moved you the way it moved us, do me a favor. Hit that like button. Every single like tells YouTube to show this story to more people. Hit subscribe and turn on notifications. We’re rescuing forgotten stories from dusty archives every single day. Stories about pilots like Robert Johnson who refused to quit even when their aircraft had 200 bullet holes. Real people. Real heroism.

Drop a comment right now and tell us where you’re watching from. Are you watching from the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, Australia? Our community stretches across the entire world. You’re not just a viewer, you’re part of keeping these memories alive. Tell us your location. Tell us if someone in your family served.

Just let us know you’re here. Thank you for watching and thank you for making sure Robert S. Johnson doesn’t disappear into silence. These men deserve to be remembered, and you’re helping make that

News

CH2 THE FARMER’S TRAP THAT SHOCKED THE THIRD REICH: How One ‘Stupid Idea’ Annihilated Two Panzers in Eleven Seconds and Changed Anti-Tank Warfare

THE FARMER’S TRAP THAT SHOCKED THE THIRD REICH: How One ‘Stupid Idea’ Annihilated Two Panzers in Eleven Seconds and Changed…

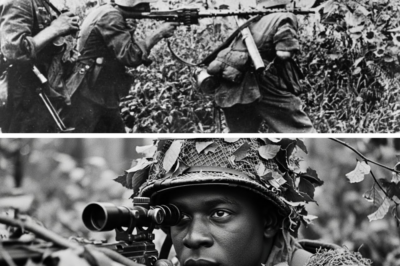

CH2 THE SIX AGAINST EIGHT HUNDRED: The Guadalcanal Miracle That Even Japan Called ‘Witchcraft’ — How a Handful of Black Marines Turned a Jungle Death Trap into the Most Mysterious Stand of the Pacific War

THE SIX AGAINST EIGHT HUNDRED: The Guadalcanal Miracle That Even Japan Called ‘Witchcraft’ — How a Handful of Black Marines…

CH2 THE INVISIBLE GHOST OF NORMANDY: How One Black Sharpshooter’s Ancient Camouflage Turned Him Into the Wehrmacht’s Worst Nightmare – Germans Never Imagined One Black Sniper’s Camouflage Method Would K.i.l.l 500 of Their Soldiers

THE INVISIBLE GHOST OF NORMANDY: How One Black Sharpshooter’s Ancient Camouflage Turned Him Into the Wehrmacht’s Worst Nightmare – Germans…

CH2 THE PLANE THEY CALLED USELESS — The ‘Flying Coffin’ That HUMILIATED Japan’s Zero and TURNED the Pacific War UPSIDE DOWN

The Forgotten Fighter That Outclassed the Zero — The Slow Plane That Won the Pacific” January 1942. The Pacific…

CH2 ‘JUST A PIECE OF WIRE’ — The ILLEGAL Field Hack That Turned America’s P-38 LIGHTNING Into the Zero’s WORST NIGHTMARE and Changed the Pacific War Forever

‘JUST A PIECE OF WIRE’ — The ILLEGAL Field Hack That Turned America’s P-38 LIGHTNING Into the Zero’s WORST NIGHTMARE…

CH2 THE ENEMY WHO LANDED BY MISTAKE: How a Wounded Japanese Zero Pilot Had To Land Onto a U.S. Aircraft Carrier

THE ENEMY WHO LANDED BY MISTAKE: How a Wounded Japanese Zero Pilot Had To Land Onto a U.S. Aircraft Carrier…

End of content

No more pages to load