THE U-BOAT NIGHTMARE: How One ‘Rejected’ American Captain’s FAKE Depth Charges Forced Dozens of Nazi Submarines to Surface in Terror – And The Outcome Was Nothing But…

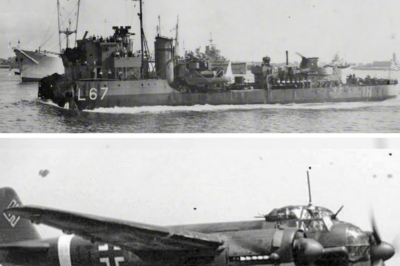

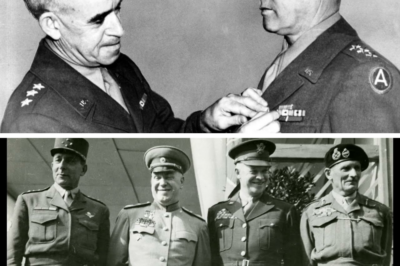

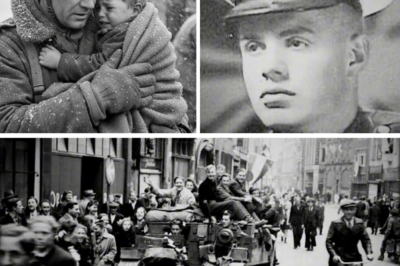

Disclaimer: Images for illustration purpose

When exhausted Royal Navy escorts were losing the Atlantic to Admiral Dönitz’s invisible wolves, one outcast officer dared to defy every order in the book. What followed in the freezing black waters of 1943 would rewrite naval warfare forever.

The North Atlantic, June 1st, 1943.

Night on the ocean was absolute—an endless dark stitched with the cold pulse of radar and the steady heartbeat of engines buried deep in steel hulls. The waves rolled heavy under a sky without stars, breaking against the bows of six British warships moving in deliberate formation. Somewhere below, beneath 500 feet of crushing pressure, a German U-boat was running for its life.

Captain Frederick John Walker, Royal Navy, stood motionless on the bridge of HMS Starling, his duffel coat snapping in the wind, his eyes fixed on the faint glow of the sonar screen below deck. He didn’t need to look at it. He already knew what it would say.

The ping—faint, regular, precise—told him everything: depth 500 feet, course northwest, speed two knots.

U-202.

He had been hunting her for sixteen hours. Most captains would have given up. Depth charges hadn’t finished the job, and his quarry was hiding far below the reach of conventional weapons. But Walker wasn’t most captains.

He had spent twenty years preparing for this moment.

Below, inside the suffocating pressure hull of U-202, Kapitänleutnant Günther Poser gripped the handles of his periscope like a drowning man. Sweat rolled down his temples despite the near-freezing air. The steel walls moaned with the strain of depth. Every creak sounded like death waiting to happen.

“Five hundred feet,” his helmsman whispered. “Holding steady.”

Poser said nothing. Through the periscope lens he had seen six British ships sweeping toward him in a formation no manual described—a line abreast, not defensive, not protecting a convoy. It looked more like fingers closing around a throat.

“This isn’t normal,” he muttered.

And he was right.

What Poser couldn’t know was that the man commanding those ships above had once been ridiculed for studying anti-submarine warfare at all. To most officers, it was the least glamorous posting in the Royal Navy—a backwater for men without ambition. But Walker had never cared for glamour. He cared about mathematics. About geometry. About the invisible physics of sound and pressure.

He had spent the better part of two decades calculating how to destroy submarines like this one, and he had built his entire career—or rather, the ruin of it—on that obsession.

The sea howled against Starling’s hull as the escort group spread out across the swell. Sonar operators bent over their consoles, faces pale in the glow of green screens. The signal came back strong—steady, rhythmic. The submarine was holding depth but not changing course. Walker smiled. He had her exactly where he wanted her.

“Number One,” he said quietly, his voice carrying just enough to reach his first officer, Lieutenant Stanley Beavan. “Signal Wild Goose and Kite. Prepare for Operation Plaster.”

The officer blinked, hesitated. “Sir, that’ll burn through the rest of our pattern stock.”

Walker didn’t even glance at him. “Then we’ll find out how well mathematics works under fire.”

He looked back over the black ocean. Every other man on that bridge could feel it—that calm, dangerous certainty. Walker was about to do something none of them had ever seen before.

He would not bombard the depths blindly, praying for luck like the hundreds of other escort commanders fighting this invisible war. He would make the ocean itself lie. He would make the enemy panic.

And he would do it with fake depth charges.

Continue below

The North Atlantic, June 1st, 1943. Zoro 30 hours. Capitan lit Gunteroser grips the periscope handles inside U202. Sweat beating on his forehead despite the frigid ocean temperature. Through the eyepiece, he counts six British warships arranged in an impossible formation. Line of breast sweeping toward him like the fingers of death.

This isn’t normal convoy defense. This is something new. Diving stations. Take her to 500 ft. His voice cracks with urgency. What Poser doesn’t know is that the commander hunting him has spent 20 years preparing for this exact moment. What he doesn’t know is that conventional depth charge attacks succeed only 5% of the time.

And the British captain above has invented something that will change those odds forever. Between January and June 1943, German yubot operating in the Atlantic sank 554 Allied merchant ships. The Wolfpacks prowled with near impunity, their commanders confident that diving deep would save them. Standard Royal Navy doctrine held that escort vessels should never leave their convoys.

The survival of Britain itself hung by a thread measured in merchant tonnage. And that thread was fraying fast. On the bridge of HMS Starling, Captain Frederick Johnny Walker stands motionless, watching his Azdic operator’s face. The sonar is pinging off U202’s hull 500 ft below. Walker knows exactly what’s about to happen.

He’s visualized this scenario hundreds of times during his wasted years stuck in shore appointments while other officers sailed to glory. While they ignored anti-ubmarine warfare as a career dead end, he studied it obsessively. While they dismissed depth charges as ineffective weapons that required impossible accuracy, he calculated angles, tested theories, filled notebooks with tactical innovations. The Admiral T considered insane.

Captain, his first officer ventures. At this depth, our standard depth charges won’t reach him. Our primers only detonate to 600 ft. Walker smiles. Not the smile of a man about to lose his prey. The smile of a man about to revolutionize naval warfare. Number one, he says quietly. Signal wild goose and kite.

prepare for operation plaster. What follows in the next 16 hours will become the longest single yubot hunt of the Second World War. What Walker doesn’t know, what none of them know is that his son Timothy is at that very moment aboard a British submarine in the Mediterranean. And Timothy Walker will never come home. To understand why Walker’s innovation was revolutionary, you must understand how desperately the Allies were losing the Battle of the Atlantic in 1942 and early 1943. The statistics were apocalyptic.

In November 1942 alone, German Yubot sank 729 160 tons of Allied shipping. 119 vessels sent to the bottom. Admiral Carl Dunitz commanded a Wolfpack fleet that operated with near impunity, surfacing at night to slaughter convoys, diving deep during the day to evade detection. The mathematics were brutal and simple.

Britain was being strangled. Without the convoys bringing food, fuel, and war materials across the Atlantic, the island nation would starve. Without those supplies, there could be no D-Day, no second front, no victory in Europe. The problem wasn’t lack of effort.

By 1943, Britain and Canada maintained 400 escort vessels patrolling the Atlantic convoy routes, destroyers, sloops, corvettes, all equipped with the latest technology. Azdic sonar to detect submerged submarines. Radar to spot surface contacts. Depth charges capable of sinking hubot if they exploded close enough. But if they exploded close enough was the critical failure point.

Analysis of depth charge attacks between 1939 and early 1943 revealed a devastating truth. The average success rate hovered between 3 and 6%. Out of every 100 depth charge attacks, 94 to 97 Ubot escaped. The weapons themselves were powerful enough. 300 lb of aml explosive that created crushing hydraulic shocks underwater. A depth charge exploding within 25 ft of a yubot’s hull would destroy it.

Within 50 ft, it would cause crippling damage. The problem was accuracy and speed. and the fundamental physics of underwater warfare. When an escort detected a submarine on Azdic, the Yubot’s hydrophone operators heard it, too. The distinctive ping of the sonar beam bouncing off their hall.

They heard the escorts propellers increasing revolutions as it charged forward to attack. A Yubot commander had precious seconds to make his move. Crash dive deeper. Go silent. turn hard to evade. The escort raced overhead, rolled depth charges off the stern set to explode at preset depths, and then had to sail clear of its own explosions before circling back. By then, the submarine had moved.

The Azdic contact was lost. The hunt began again from scratch. Yubot commanders learned the dance. When they heard propellers accelerating above them, they dove beyond 600 feet, deeper than standard British depth charge primers could reach. Or they crept along at minimal speed, making themselves nearly invisible to sonar.

Or they released oil and debris, faking their own destruction while slipping away silently. The British tried everything. larger depth charge patterns, more escorts per convoy, better training, new weapons like the Hedgehog, a forwardthrowing mortar that fired contactfuse projectiles ahead of the attacking ship.

The Hedgehog achieved better results than conventional depth charges, but it required perfect aiming and was effective only at close range. The expert consensus was clear. Depth charges were fundamentally limited weapons. To sink a submarine, you needed luck in overwhelming numbers. Most senior Royal Navy officers believed that convoy escorts should stay close to their merchant ships, defending them reactively rather than hunting offensively.

The Admiral T’s standing order stated explicitly, “The object of the escort group while on duty is to ensure the safe and timely arrival of the convoy.” And meanwhile, the casualty figures climbed. In June 1942 alone, 135 Allied merchant ships were sunk. The worst single month of the war. Thousands of sailors died in the freezing Atlantic. Their ships torpedoed beneath them. Every sinking meant fewer supplies reaching Britain.

Every lost tanker meant less fuel for aircraft and tanks. Every sunken freighter meant hungry civilians and postponed military operations. By early 1943, Britain was losing the Battle of the Atlantic. And conventional tactics offered no solution. This is where Captain Frederick John Walker enters the story.

And here’s what makes it remarkable. When Walker took command of the 36th Escort Group in September 1941, he was by every official measure a failed officer. Born June 3rd, 1896, Walker had joined the Royal Navy at age 13. He graduated top of his class at Dartmouth Royal Naval College, won the King’s Medal, served competently in World War I, but then his career stalled.

In the status obsessed peacetime Royal Navy, Walker made a catastrophic error. He became fascinated by anti-ubmarine warfare. This was career suicide. In the 1920s and 1930s, anti-ubmarine warfare was considered a backwater specialty, unglamorous and unfashionable. Ambitious officers sought commands on battleships and cruisers.

Walker instead volunteered for the newly formed anti-ubmarine school at HMS Osprey in Portland. He studied Azdic. He experimented with depth charge patterns. He filled notebooks with tactical theories while his peersworked and climbed the promotion ladder. In 1937, Walker was appointed experimental commander at the anti-ubmarine school, a research and development position that kept him ashore. It was one of the happiest periods of his life.

For the first time, he could live at home with his wife Eileene and their four children. He could focus entirely on solving the problem that obsessed him, how to hunt and kill submarines efficiently. But the Royal Navy doesn’t promote researchers. It promotes officers who command major warships. When the promotion list for captain was published, Walker’s name wasn’t on it.

He’d been passed over, the polite term for a career dead end. At age 43, Commander Walker faced mandatory retirement, and then Germany invaded Poland. When World War II erupted, Walker pleaded for a sea command. The Admiral T assigned him to Dover as a staff officer, more administrative work. He watched the Battle of Britain from Dover Castle, filed paperwork, and became increasingly desperate as yubot casualty reports flooded in.

Here was the crisis he’d prepared for his entire adult life, and he was trapped behind a desk. Walker bombarded his superiors with transfer requests. Everyone came back. Request not approved. Finally, an old friend intervened. Captain George Crey, director of anti-ubmarine warfare at the Admiral T, wrote personally to Admiral Sir Percy Noble, Commanderin-Chief Western Approaches.

Walker is the best anti-ubmarine warfare specialist we have. He’s wasted at Dover. Give him a ship. In September 1941, 45-year-old Commander Walker, passed over for promotion, relegated to administrative duties, considered too specialized and too theoretical by his superiors, received orders to Liverpool. He would command HMS Stor, a small sloop.

He would lead the 36th escort group. Nine ships, mostly corvettes, crewed by weekend sailors and reservists. Nobody expected much. Walker wasn’t a destroyer captain. He’d never commanded a major warship in combat. He was a theorist, an experimentter, a man whose career had demonstrabably stalled. But Walker had something none of his critics possessed.

20 years of obsessive study about how to kill submarines. And he was about to prove that theory properly applied could change the course of a war. Walker’s tiny cabin aboard HMS Stor became his laboratory. By candlelight during the autumn of 1941, he drafted a document that would terrify the German Yubot fleet, 36th escort group operational instructions.

The Admiral T’s standard escort doctrine filled volumes with cautious protocols. Walker’s orders ran to five stark paragraphs. Paragraph one redefined his mission. The object of the group while on escort duty is to ensure the safe and timely arrival of the convoy concerned. It is not possible to protect the convoy completely from enemy attacks.

These must be accepted. The only practicable course is to ensure that any enemy craft which attacks is destroyed. Paragraph 2 was more explicit. A yubot cighted or detected is immediately to be attacked continuously without further orders with guns, depth charges, and/or ram until she has been destroyed. No waiting for instructions, no defensive formations. If you found a yubot, you killed it.

But the innovation that would change everything came next. Walker called it Operation Buttercup, named after his wife’s family nickname. Standard doctrine held that when a yubot torpedoed a merchant ship at night, escorts should stay with the convoy. The submarine had already attacked. It would submerge and escape.

Chasing it meant leaving the other ships vulnerable. Walker’s Operation Buttercup did the opposite. The moment a torpedo struck, escorts would race toward the sinking ship, illuminate the entire area with star shell and rockets, and blanket the kill zone with depth charges. The theory was simple. Ubot attacked at night on the surface, running fast to reach firing positions.

After the attack, the submarine either lurked near the burning wreck, watching for rescue vessels, or fled on the surface at high speed. Standard procedure let them do both safely. Buttercup turned night into day and the ocean into hell. If the Aubot stayed on the surface, guns and search lights would find it.

If it dived to hide, it was trapped in a saturation bombardment of depth charges. Either way, its captain faced a terrible choice. Be hunted on the surface or be crushed below. When Walker submitted Operation Buttercup to headquarters, the response was immediate and scathing. “That is insane,” a staff officer at Darby House told him. “You’ll leave the convoy undefended.

The Yubot will escape and you’ll waste depth charges illuminating empty ocean.” Another senior officer was blunter. Commander Walker, this violates standing admiraly orders. Escorts do not abandon their positions. I cannot approve this. Walker’s response was respectful but immovable. Sir, standing orders are why we’re losing. The Ubot know our doctrine.

They attack when and where we’re predictable. I’m asking for permission to surprise them. The debate went up the chain of command until it landed on the desk of Admiral Sir Percy Noble himself. Noble reader’s proposal. He noted the logic. He recognized the tactical reasoning from a man who’d spent two decades studying anti-ubmarine warfare.

Noble made a decision that would alter history. He approved Operation Buttercup with amendments. And then he did something more. He ordered Darby House to distribute Walker’s tactics fleetwide with the official endorsement that this provided the maximum chance of sinking Hubot at night. The Passover commander had just rewritten Royal Navy doctrine.

The true test came on December 14th, 1941. Convoy HG76 departed Gibralar bound for Britain. 32 merchant ships loaded with food, fuel, and ammunition. Walker’s 36th escort group provided the close escort. Nine ships against the Wolfpacks gathering in the Atlantic.

Intelligence intercepts confirmed that at least 10 Ubot were positioning for attack. What followed became legendary. On December 17th, Walker ordered the escort carrier HMS Audacity to launch Dawn patrols, violating standard doctrine that held carriers were too valuable to risk offensively. A Martlet fighter spotted U131 on the surface 22 mi from the convoy. Walker dispatched four escorts to hunt it down.

U131’s captain dived, then surfaced hours later, believing himself safe. HMS Stanley found him. The martlet strafed the conning tower. Shells from four escorts penetrated the hull. U131 sank. 55 German sailors were pulled from the water. The next day, U434 made the fatal error of shadowing too close in excellent visibility. HMS Stanley spotted the periscope.

Three escorts pounded the submarine with depth charges until it surfaced, crippled. 93 more prisoners. Then came U574. Its commander, seeing the convoys unusual defensive pattern, tried a bold surface run. Walker and Stor detected it, called in HMS Pensamman and Convalulus. The submarine fired two torpedoes at Convalulus. Both missed.

Then U574 turned on HMS Stanley and blew the destroyer apart. Walker watched his ship die, then charged U574 alone. The submarine crash dived. Stork’s Azdic locked on. Walker pursued for hours. At midnight on December 19th, U574’s batteries gave out. It surfaced directly ahead of Stork, boughs high, caught in moonlight. Starshell, commence.

Walker’s voice was ice calm. The night erupted. Six escorts opened fire simultaneously. Walker increased speed to Ram. His first officer shouted, “Captain, she’s badly hit. We can take prisoners.” Walker’s response was instant. I’m not stopping. Ram her.

Stork struck U574 a glancing blow, rolled her over and dropped a shallow depth charge pattern as the Yubot sank. The German captain, Capitan Litinet Gunther Dietrich, survived and was pulled aboard. He looked at Walker in disbelief. You don’t fight like British captains, you fight like a wolf. Walker’s reply entered Royal Navy legend. Hair Capitan, we are the wolves now.

HG76 reached Liverpool on December 23rd, having lost two merchant ships and the escort carrier Audacity to yubot attacks. But Walker’s group had sunk four Yubot and crippled another. For the first time in the war, a convoy battle had cost the Germans more than they’d inflicted. But the reaction at Darby House wasn’t universally positive. A staff officer confronted Walker during his debriefing.

You left the convoy undefended to chase submarines 40 m away. You wasted depth charges on hunts that lasted hours. You risked a collision ramming U574 when she was already sinking. These tactics are reckless. The room erupted. Walker’s officers defended him. The Admiral T statisticians presented data. Four confirmed kills in 10 days. Unheard of success.

Other senior officers argued that Walker had merely been lucky, that his aggressive tactics would lead to disaster when the Hubot adapted. Then Admiral Sir Percy Noble arrived. He listened to both sides. Then he spoke, “Gentlemen, I don’t care about conventional wisdom. I care about dead yubot. Commander Walker has killed more submarines in two weeks than most escort groups kill in a year. His methods work.

We will study them, refine them, and implement them fleetwide. Noble turned to Walker. Commander, you’re promoted to captain, and I’m giving you something even better. Command of a new support group, not tied to convoys. Roving Commission. Your sole mission is to hunt and kill yubot wherever you find them. Walker saluted.

For the first time in years, he allowed himself to smile. But the real breakthrough was still ahead. Because Walker had already designed the tactic that would become his masterpiece. He’d tested it in training exercises. He’d calculated the geometry. He drilled his crews on the precise coordination required.

He called it the creeping attack. and it would change anti-ubmarine warfare forever. If you’re learning how one captain’s obsession revolutionized naval warfare, make sure to hit subscribe and turn on notifications. The battle that proves his genius is coming up next. And it involves tactics so unconventional the Germans thought they were impossible.

In April 1943, Captain Walker took command of HMS Starling and formed the second support group. Six modern sloops purpose-built for submarine hunting. Starling, Wild Goose, Signnit, Ren, Woodpecker, and Kite. These weren’t convoy escorts. They were predators. Walker’s first order to his commanding officers was characteristically direct.

The object of the second support group is to destroy yubot, particularly those which menace our convoys. Our job is to kill. No matter how many convoys we shepherd safely through, we shall have failed unless we slaughter yubot. Now he could finally implement the tactic he’d perfected on paper, the creeping attack.

The problem with conventional depth charge attacks was simple. The attacking ship’s propellers alerted the submarine. The moment a yubot captain heard those propeller revolutions increasing, he knew an attack was imminent. He could dive deeper, turn sharply, release decoys, go silent. By the time the attacking ship reached the target position and dropped charges, the submarine had moved.

Walker’s creeping attack eliminated the warning. Here’s how it worked. Two ships hunted together. The directing ship located the Yubot on Azdic, then reduced speed to barely three knots, so slow that its propellers made almost no noise. It positioned itself 1500 yd from the submarine and held contact, feeding continuous course corrections via signal lamp to the second vessel. The attacking ship crept forward at 5 knots, walking speed in nautical terms.

Its propellers turned so slowly that the submarine’s hydrophone operators heard nothing unusual. No racing engines, no accelerating screws, just the normal background ocean noise. The directing ship guided the attacker precisely over the submarine’s position. Left 5° steady, steady. Now, the attacking ship rolled depth charges in a pattern.

The submarine’s first warning came when the charges exploded around its hull. No time to dive, no time to evade, just crushing hydraulic shock waves and the sound of their own hull buckling. The mathematics were brutal. Standard depth charge attacks had a 5 to 6% success rate.

The creeping attack by eliminating the submarine’s warning and positioning the charges with precision achieved success rates above 30%. A six-fold improvement. But proving it required perfect coordination and patience. Lots of patience. On June 1st, 1943, the second support group detected U202 in the North Atlantic. Capitan litnet Gunterposer was a veteran commander returning from a special mission to the United States.

His ninth war patrol, 27 years old, capable and clever. Poser heard Starling’s Azdic pinging off. His Hall and Dove immediately to 500 ft. Walker ordered a standard attack. 10 depth charges exploded. U202 survived. Poser went deeper. 700 ft. 800. Conventional depth charge primers couldn’t reach that depth. Walker settled in to wait.

He knew U202’s limitations. At 800 ft, Poser was below his submarine safe operating depth. The pressure hull groaned and buckled. He couldn’t stay down indefinitely. His batteries would drain. His air would foul. Eventually, physics would force him to surface. For 12 hours, Walker tracked U202 slowly across the ocean.

His Azdic operator called out bearing changes. Walker plotted the submarine’s course. When darkness fell, he positioned his ships and waited. At 2100 hours, Walker turned to his first officer. He’ll surface at midnight. His air will be critical by then.

Signal Wild Goose and Kite to prepare for operation plaster, but afterwards we’ll try the creeping attack properly. At 002 on June 2nd, U202 surfaced explosively. Boughs high, crew pouring onto the conning tower. Walker six ships opened fire immediately. Star shells illuminated the night. Poser tried to run on the surface. For 30 minutes, HMS Starling chased U202, guns blazing, while the submarine twisted and turned. Walker ordered, “Cease fire.

All ships, prepare for creeping attack. Wild Goose, you have the directing position. Kite, come to attack course.” U202 crash dived. Wild Goose’s Azdic found her immediately, damaged, leaking oil, running deep but slow. Wild goose reduced to three knots and held contact. Kite crept forward at five knots. The range closed. 1,000 yards. 800 500.

Attack now. Wild goose signaled. Kite rolled a full pattern. 86 depth charges in 3 minutes. The ocean convulsed. Starling and Woodpecker added their own patterns. The sustained barrage guided by Wild Goose’s precise Azdic tracking pounded U202 relentlessly. At 0030, U202 surfaced again. Conning tower ablaze. Hull ruptured.

Poser stood at the periscope column, drew his revolver, and ordered, “Abandon ship.” His officers had already jumped overboard. Poser followed them into the freezing Atlantic, fully intending to die rather than be captured. HMS Starling pulled alongside and dragged him from the water anyway. 16 hours from first contact to confirmed kill.

The longest single yubot hunt of the war, and the creeping attack had worked exactly as Walker predicted. German reaction was immediate and terrified. Surviving Yubot commanders reported back to Admiral Dunit’s headquarters. British tactics have changed. We receive no warning before attacks. Depth charges explode precisely on our positions.

Multiple ships coordinate perfectly. Recommend extreme caution in North Atlantic. Dunit ordered an investigation. How are the British achieving this accuracy? New weapons, better Azdic, captured code books. One captured yubot captain told his interrogators, “Your escorts now hunt like submarines, silent, patient, deadly. We thought you couldn’t track us precisely while moving slowly.” We were wrong.

Between June and August 1943, Walker’s second support group sank sixot in a single 3-week patrol. U202, U1 Hoy19, U40049, U504, U461, and U454. Then they sank three more Yubot in a single day during a running battle in the Bay of Bisque. The Germans called Walker Duryaged Group of Terror, the terror hunting group. Walker’s tactics spread throughout the Royal Navy.

Every escort commander studied his methods. The Admiral T published Walker’s fighting instructions as official doctrine. Convoy losses plummeted. Yubot losses skyrocketed. May 1943 became Black May for the German submarine fleet. 41 Yubot sunk in a single month. Dunit was forced to withdraw his Wolfpacks from the North Atlantic.

The creeping attack, dismissed by staff officers as impossible, had turned the tide of the Battle of the Atlantic. Between 1943 and 1944, ships under Walker’s direct command sank 20 yubot, more than any other Allied commander. HMS Starling herself was credited with 14 kills. The success rate for Walker’s creeping attacks average 9.

4% 4% confirmed kills, nearly double the fleet average, and required 40% fewer depth charges per kill. Thousands of merchant sailors reached Britain alive because walkers hunters cleared their routes. Countless tons of food, fuel, and war material arrived safely. The logistics for D-Day depended on Atlantic convoys Walker’s tactics protected.

One Royal Navy analysis concluded, “Captain Walker’s innovations shortened the Battle of the Atlantic by at least six months. His tactics saved an estimated 300 merchant ships and 30,000 lives.” The story gets even more remarkable and tragic. Stay with me for the ending because what happened to this brilliant captain will surprise you.

and make sure you’re subscribed so you never miss stories like this. Captain Frederick Johnny Walker never lived to see the end of the war he helped win. By mid 1944, he’d been at sea almost continuously for 3 years. The second support group operated on brutal schedules. 20-day patrols in the Atlantic, 3 days in port, then back to sea. Walker never rested.

When his ships were in Liverpool, he worked 18-hour days at Darby House headquarters, refining tactics, training new commanders, analyzing combat reports. His officers grew worried. Walker looked exhausted, gray-faced, older than his 48 years. His first officer suggested he take leave. Walker refused. Too many Yubot still out there.

On July 7th, 1944, while conducting routine paperwork at the Royal Navy Hospital in Liverpool, Walker suffered a massive cerebral thrombosis. He died 2 days later. The official cause, exhaustion and overwork. His funeral service at Liverpool Cathedral on July 11th drew over 1,000 mourners. Admiral Sir Max Horton delivered the eulogy. Captain Walker destroyed more enemy submarines than any officer in naval history. But more than that, he taught us how to win.

The service concluded at the Liverpool docks. Walker’s flag draped coffin was placed aboard HMS Hesperis. The escort sailed into Liverpool Bay where surrounded by the surviving ships of his second support group, Captain Frederick John Walker was buried at sea. Among those attending were dozens of merchant Navy sailors who owed their lives to Walker’s tactics.

One elderly seaman was heard saying quietly to the man beside him, “We came home because of him, because of what he figured out.” Walker never sought fame. He refused interviews. He deflected praise to his crews. When reporters asked him about his tactics, he simply said, “I worked out the mathematics. good men executed them properly. He never learned that his innovations would become the foundation of modern anti-ubmarine warfare.

Every NATO Navy today teaches variance of Walker’s coordinated team hunting tactics. Helicopters and submarines now fill the directing and attacking roles using the same principles Walker developed aboard steam powered sloops with Azdic operators manually tracking targets. The creeping attack specifically remains classified doctrine in several naval services.

The concept one platform tracks silently while another attacks with precision underpins everything from modern torpedo runs to anti-air missile coordination. Production statistics tell the story. Between 1943 and 1945, Allied forces sank 571 German hubot. Walker’s tactics directly or indirectly influenced the destruction of more than 300 of those.

His 36th escort group and second support group personally sank 25, an unprecedented record. In 1998, a statue of Captain Walker was unveiled at the Pierhead in Liverpool overlooking the Murzy River. He stands in his duffel coat, binoculars raised, scanning the horizon. The inscription reads simply, “Captain FJ Walker, CBD DSO bao, most successful yubot hunter.

” The three bars after his DSO represented three additional distinguished service orders. The second highest decoration for gallantry in the Royal Navy. Only one man in World War II earned more. But perhaps the greatest tribute came from a German yubot commander asked years after the war what changed the battle of the Atlantic. His answer was direct.

The Allies learned to hunt in packs like us. One British captain taught them how. After him, the Atlantic became our graveyard. That captain was a passed over theorist whom the peacetime Navy considered a failure. A man who spent 20 years preparing for a war he prayed would never come.

A man who lost his own son to the sea while saving thousands of others. The moral of this story isn’t about genius or heroism. Though Walker possessed both. It’s about the power of obsessive expertise. About how one person who truly masters a problem can change the course of history if someone with authority is willing to listen.

In 1941, the Royal Navy was losing the Battle of the Atlantic using tactics written in manuals by committees. Captain Walker rewrote those manuals with mathematics and patience and a ruthless willingness to prove conventional wisdom wrong. The Yubot called him terror. History should remember him as proof that sometimes the misfits, the specialists, the passed over officers nobody wants.

Sometimes they’re exactly what you need to win the war nobody thought you could

News

CH2 90 Minutes That Ended the Luftwaffe – German Ace vs 800 P-51 Mustangs Over Berlin – March 1944

90 Minutes That Ended the Luftwaffe – German Ace vs 800 P-51 Mustangs Over Berlin – March 1944 March…

CH2 The “Soup Can Trap” That Destroyed a Japanese Battalion in 5 Days

The “Soup Can Trap” That Destroyed a Japanese Battalion in 5 Days Most people have no idea that one…

CH2 German Command Laughed at this Greek Destroyer — Then Their Convoys Got Annihilated

German Command Laughed at this Greek Destroyer — Then Their Convoys Got Annihilated You do not send obsolete…

CH2 Why Bradley Refused To Enter Patton’s Field Tent — The Respect Insult

Why Bradley Refused To Enter Patton’s Field Tent — The Respect Insult The autumn rain hammered against the canvas…

CH2 Germans Couldn’t Stop This Tiny Destroyer — Until He Smashed Into a Cruiser 10 Times His Size

Germans Couldn’t Stop This Tiny Destroyer — Until He Smashed Into a Cruiser 10 Times His Size At…

CH2 When a Canadian Crew Heard Crying in the Snow – And Saved 18 German Children From Freezing to Death

When a Canadian Crew Heard Crying in the Snow – And Saved 18 German Children From Freezing to Death …

End of content

No more pages to load