The “Soup Can Trap” That Destroyed a Japanese Battalion in 5 Days

Most people have no idea that one of the most effective weapons the Marines used in the Pacific was a soup can. Yes, a dented empty soup can. And the moment you understand why, you’ll see how one impossible idea shattered a Japanese battalion, rewrote sniper doctrine, and changed the battlefield in ways historians still overlook.

Because what happened on Buganville wasn’t luck, and it wasn’t marksmanship. It was a psychological trap so simple, so absurd that the Japanese had no defense for it. And 112 soldiers died trying to figure it out. If you stay until the end, you’ll understand the real secret. Not how the trick worked, but why it worked and why this forgotten 5-day operation became one of the most devastating and least understood turning points of the Pacific campaign.

A battlefield weapon made from garbage. a result no one believed was possible and a truth almost no one was ever told. Most snipers are created through training. Thomas Michael Callahan wasn’t. He arrived at sniper school already carrying something the Marine Corps couldn’t teach and something the Japanese would never anticipate.

Callahan grew up in the Bitterroot Mountains of Montana where a missed shot wasn’t just a mistake, it was a lesson. If you misread the wind by an inch at 600 yd, you didn’t wound an elk. You simply watched it disappear, knowing you wouldn’t get a second chance.

That environment shaped him long before the Marine Corps ever issued him a rifle. He didn’t learn patience in a classroom. He didn’t learn discipline from an instructor. He learned because the mountains punished anyone who tried to rush. That mattered more than anyone realized. Because the truth, the one most people miss, is that Callahan’s later soup can trick, wasn’t born from improvisation.

It was born from pattern recognition. From watching how living things behave when they sense something unusual, from knowing exactly when curiosity overrides caution. People thought he invented a clever gimmick in the jungle of Buganville. He didn’t. He simply applied lessons he’d been absorbing since childhood.

Lessons that had nothing to do with war, but everything to do with survival. When Callahan enlisted after Pearl Harbor, he blended in with thousands of other volunteers. Nothing about him looked extraordinary, but the first time he stepped onto a rifle range. The instructors noticed something unsettling. He didn’t shoot like the others.

Most Marines fired as soon as sights touched center mass. Callahan waited. He watched the grass bend one way, the heat mirage drift another. The target sway half an inch in the wind. He fired only when all three lined up. To the instructors, it looked slow. To Callahan, it was the only moment that made sense.

He posted one of the highest scores of the training cycle, not because he was a gifted marksman, but because he refused to take shots that weren’t on his terms. That mindset would become the backbone of everything he did on Buganville. 3 days later, he was transferred to Scout Sniper School. Here’s where the first major misunderstanding about Callahan begins.

People assume sniper school made him deadly. It didn’t. What school did was give language and structure to instincts he already had. Gunnery Sergeant William Henderson, the man responsible for teaching sniper psychology, spotted it immediately.

While other students treated the rifle as their primary weapon, Callahan treated it as the last step in a longer process. Henderson’s first lecture began with a line that stayed with Callahan forever. The shot is the end of the operation, not the beginning. One. Then Henderson explained the part that separates ordinary snipers from predators. A sniper who seeks targets is predictable.

A sniper who creates targets is a threat. And a sniper who shapes the enemy’s decisions before they even know he’s there becomes something else entirely. Most students struggled with that concept. Callahan didn’t struggle. He leaned into it because that was exactly how he hunted elk. You didn’t chase the animal.

You forced it to make the one move it couldn’t afford to make. During stalking exercises, the difference became obvious. Other students tried to get close. Callahan tried to get forgotten. In the final test, instructors with binoculars scanned the field for hours. They spotted movement from nearly everyone, but Callahan, nothing. No shift of grass, no flash of metal, no silhouette, out of place.

Nine hours later, he simply stood up calm and rested and said, “I’ve been ready for about 15 minutes. We Henderson pulled him aside after graduation. You’re thinking like a hunter,” he told him. “Good, but stop assuming the enemy is an animal. Animals run from danger. Soldiers investigated.

Learn that difference and you’ll outthink anyone you face.” Reese’s that single correction animals flee. Soldiers investigate would become the hinge upon which the entire Buganville operation turned. And this is the part almost no historical account ever emphasizes. Callahan’s true weapon wasn’t accuracy. It was his understanding of curiosity. He didn’t beat the Japanese because he was the better shot.

He beat them because he knew when men couldn’t resist looking at something, even when they shouldn’t. That insight wasn’t dramatic. It wasn’t glamorous, but it was the seed of the idea that would later destroy a Japanese battalion’s ability to trust its own senses.

A childhood spent reading wind, a sniper school lesson, about human behavior. A mind that understood the fatal difference between instinct and discipline. All of it was about to collide on an island the Japanese believed was secure. And within days, that belief and their entire intelligence network would crumble under the weight of a trick so absurd that no one ever imagined it could work.

Callahan arrived on Buganville, expecting a brutal fight. He didn’t expect the moment that would define everything. For a week, he operated like any other marine, holding lines, running patrols, trying to make sense of a jungle where every shadow looked like a firing slit. Japanese snipers were everywhere and nowhere at once. They rarely fired twice from the same spot. They knew the terrain.

They owned the treetops. But the shot that changed Callahan’s life wasn’t one he fired. It was the one that killed the man beside him. November 8th, 1,943. He and his spotter, Corporal James Rivera, were observing a suspicious patch of brush. Nothing special, nothing obviously hostile. They’d lifted their binoculars a thousand times before. Rivera raised his for 3 seconds.

That was long enough. A single round, clean, precise, silent, until it wasn’t cut the air from a concealed firing point nearly 600 yd away. Rivera dropped instantly. No struggle, no final words, just the thud of a body collapsing into the mud. Kalahan didn’t move, not because he was brave, because he understood immediately what had happened.

A sniper that disciplined doesn’t fire twice. A sniper that skilled doesn’t expose himself with follow-ups. Rivera wasn’t killed by a lucky shot. He was killed by someone Callahan recognized in an instant. A predator who understood patterns as well as he did.

So Callahan lay there 30 minutes, unmoving, barely breathing, letting the jungle settle around him, not scanning wildly, not panicking, not calling in artillery. He did something far more dangerous, he thought. He replayed Rivera’s movement, the angle of the binoculars, the arc of the bullet, the way the Japanese sniper had positioned himself to see without being seen. Piece by piece, the geometry formed in his mind.

He knew exactly what kind of man he was dealing with. Disciplined, patient, methodical, someone who would not fall for standard counter sniper tactics. Callahan retrieved Rivera’s body himself, carried him back through the mud, and went straight to his commanding officer. He didn’t ask for reinforcements. He didn’t ask for revenge fire missions.

He asked for something officers didn’t usually hear from enlisted men. Permission to think outside doctrine. Callahan wasn’t angry when he made the request. He was focused. Sir, we can’t outshoot him, he said quietly. We have to outthink him. And that means doing something he’s not trained to recognize. Everyone, Captain Morrison stared at him.

What exactly does that mean? Well, Callahan didn’t give details yet because the idea wasn’t finished. He only knew one thing for certain. If he used the same tactics the Japanese expected, he would die. Rivera had been killed by someone who anticipated reactions, not someone who made mistakes. To beat that kind of opponent, Callahan needed something neither side had ever put into doctrine, something that didn’t look like a tactic at all.

That night, sitting alone in a shallow foxhole, he struggled to find it. He wasn’t searching for a weapon. He was searching for a blind spot, a flaw in Japanese training, a human instinct strong enough to override discipline. He thought about predators and prey. He thought about Henderson’s warning. Animals run. Soldiers investigate.

One thus he thought about all the times he’d watched elk freeze at an unfamiliar sound and the times he’d seen hunters make the fatal mistake of standing to look. Why do people investigate things they shouldn’t? Why do soldiers expose themselves to unknown stimuli? Callahan’s answer came from a direction he didn’t expect.

While eating his evening ration, a can of chicken noodle soup, he set the empty tin beside him. As the sun dropped behind the ridge, the last rays of light struck the can’s rim and threw a sharp beam across the jungle floor. Callahan froze. A flash, a pinpoint of reflected sunlight, a signal that wasn’t a signal, something so small, so ordinary that no doctrine on earth had prepared anyone to interpret it. He rotated the can slightly. The beam swept left. Another rotation.

The beam swept right. Not a weapon, not a tool, not even equipment, just trash, but trash that could do something no rifle could. It could trigger human curiosity without revealing anything about the shooter. In that moment, the idea solidified. Not the trick yet, but the principle. The Japanese sniper who killed Rivera was disciplined.

But even the most disciplined soldier must investigate the unknown. Curiosity isn’t a weakness. It’s a necessity. Callahan didn’t need better accuracy. He needed to manufacture the exact moment when a sniper forgets fear and leans out to look. That night, the soup can sat beside him on the dirt. And Callahan understood for the first time the paradox that would define the next 5 days. If he couldn’t make the enemy fear him, he would make them curious.

Curious enough to die. The next morning, Callahan didn’t report to a firing line. He reported to a pile of garbage. While the rest of the battalion prepared for another day of jungle chess with an invisible enemy, Callahan quietly collected what everyone else ignored. Empty ration cans, bits of wire, broken stakes, the kind of junk men kick aside without thinking. To most Marines, it looked ridiculous.

To Callahan, it looked like leverage. He picked five soup cans that still had enough reflective surface to catch sunlight. Not because they were special, but because they were consistent, predictable, controllable. He understood something crucial. If you want to manipulate a human response, the trigger must behave the same way every time.

He wasn’t building weapons. He was building stimuli. Before dawn on November 9th, he moved 300 yd behind friendly lines to a clearing that overlooked Japanese troop planes. Not close, not dangerous, just close enough to watch their patterns. He planted the cans on thin sticks at slight upward angles, not random, but calculated.

He didn’t need the cans to signal. He needed them to almost signal because the goal wasn’t communication. The goal was ambiguity. He rigged simple string controls to adjust the angles by a few degrees. Not enough to look like a trick, but enough to change the beam. The idea was brutally simple. A single flash looks like chance.

A second flash looks like coincidence. A third flash from a different spot looks like intent. And soldiers cannot ignore intent. Not when their job is observation. At 6:15, the sun cracked through the canopy. The first can flared a thin, sharp reflection for barely 3 seconds. Then silence. 30 seconds later, a different can flashed briefly. Then another.

No pattern, no rhythm, just enough consistency to suggest that someone was signaling. Callahan stayed prone 300 yd south, far from the cans. He wasn’t watching the flashes. He was watching the Japanese. 20 minutes passed. Nothing that was expected. Curiosity takes time to overcome discipline. Then it happened.

A figure eased out from the treeine. Not bold, not careless. The posture said everything. He wasn’t surfacing to attack. he was surfacing to understand. He lifted binoculars. That was all Callahan needed. One controlled exhale, one steady squeeze. The soldier collapsed backward, disappearing into brush.

The soup cans flashed again into empty jungle, indifferent to the death they had caused. The Japanese response was immediate and predictable. Mortars hammered the area where the cans had been planted. Shell after shell, precise, disciplined, furious. But Callahan had already shifted position. He wasn’t interested in the mortars. He was interested in what they meant. Mortar fire is not random anger. It means the enemy believed the flashes were a real threat.

In one test shot, Callahan had accomplished three things. He confirmed Japanese doctrine. They investigate anomalies, then suppress aggressively. He learned their reaction time. It took roughly 20 minutes for curiosity to outweigh caution. He proved the central paradox of his idea. Something as stupid as a soup can shape enemy decision cycles.

That evening, he refined the system. He punched small holes in some cans, creating diffused glints. He smeared mud on others to reduce brightness. He experimented with angles that would flash only at certain minutes in the morning. He wasn’t improvising anymore. He was engineering a psychological instrument.

When he brought his findings to battalion that night, he expected skepticism. Instead, Lutin and Colonel O’Brien asked just one question. How many men do you think this could take out if the enemy doesn’t adapt? Sigh of demand. Callahan didn’t exaggerate. 20 to 30 in a week, he said. Maybe more if they react the way trained observers always react. We get our crew. O’Brien didn’t blink.

Then you have five days. A security team, full freedom of maneuver. Your objective is simple. Break their ability to see the battlefield. Well, that order mattered more than anyone understood. It wasn’t kill snipers. And I it wasn’t thin their numbers. I said it was something far more dangerous. Destroy their perception. Because when an army can’t trust what it sees, it can’t act.

And when it can’t act, it loses not by force, but by paralysis. Those five soup cans, things Marines usually kicked aside without thinking, had just become the core of an operation that would wipe out over a 100 enemy soldiers in less than a week and collapse a Japanese intelligence network that had taken months to build. The trick wasn’t magic. It wasn’t luck. It wasn’t even about marksmanship.

It was the weaponization of a human reflex. when something unusual happens. We look and for the next 5 days that reflex would be fatal. The operation began the next morning, November 10th. And from the very first hour, one thing became clear. The Japanese weren’t being hunted by a sniper. They were being manipulated by a system.

Callahan didn’t shoot because he had a target. He shot because he created one. Callahan chose a sector where Japanese movement was predictable, not because they were careless. But because every army, no matter how disciplined, repeats patterns under stress, he planted six soup cans in a wide arc, each angled to catch sunlight at slightly different moments.

When the sun rose, the cans didn’t blink randomly. They blinked with just enough structure to look intentional. One long flash, a shorter one, then silence. To an untrained eye, it meant nothing. To a trained observer, it looked like visual communication. That was the point.

Two Japanese soldiers eventually emerged from a concealed bunker, pointing toward the flashing cans. One lifted binoculars. They were focused entirely on the signal source. Oh. In with those. Callahan wasn’t anywhere near it. He was 90° to the flank where no one expected a threat. Two shots, two bodies down. By sunset, Callahan had nine confirmed kills, all created. Not discovered. The cans didn’t reveal the enemy.

They shaped enemy behavior until revealing themselves became inevitable. Japanese doctrine had a blind spot. It relied on observation. Callahan turned observation into a liability. If day one proved the method worked, day two proved something else. Callahan wasn’t fighting infantry anymore. He was going after the man who killed Rivera.

A tree 700 yd out had become infamous. Marines reported being shot from that direction, but could never locate the sniper. No muzzle flashes, no sound cues, no repeated mistakes. A professional, Callahan knew the man wouldn’t chase random flashes. His discipline was too high. So Callahan didn’t target the sniper. He targeted the sniper’s priorities. He built a fake forward command post.

Marines moving maps, radios, equipment in deliberate visible motions. Beside them, soup cans flashed in patterns that mimicked tactical signaling. To the Japanese sniper, this was gold. A vulnerable command node telegraphing information. He had to investigate. Callahan positioned himself nowhere near the fake post. Instead, he aimed at the sniper suspected tree from a northern angle.

For 90 minutes, nothing moved. Then, a tiny shift in foliage. Not wind, not chance. A micro movement made by a man preparing to kill. Callahan calculated Yiddi yards 8 mph’s crosswind, 30 in of elevation, 2 ft of wind hold. At 11:27, the Japanese sniper eased a rifle barrel into the gap. Callahan fired once.

2 seconds later, the body fell through the branches, the end of a hunter who had never expected to be hunted by light. It wasn’t a duel of marksmanship. It was a duel of decision cycles, and Callahan had forced the sniper into a predictable one. By November 11th afternoon, an odd pattern formed. Japanese soldiers no longer responded immediately to flashes. Fear had begun to counteract curiosity.

On the surface, that looked like progress for them. In reality, it opened the door to something far worse. Because fear changes behavior, and changed behavior is predictable. Now Callahan didn’t have to guess how they’d react. He knew they would hesitate. They would pull centuries back. They would cluster undercover. They would centralize information to officers.

So Callahan escalated. He introduced multiple nodes, more cans placed farther apart. Not blinking randomly, but blinking in sequences that resembled patrol coordination, artillery observation, defensive repositioning signals. The Japanese didn’t know if the flashes were real communications or traps, and uncertainty is deadlier than fear. 16 more soldiers died on day three.

Not because they were reckless, but because commanders needed information, and information required exposure. The paradox deepened. The more disciplined the Japanese became, the easier they were to manipulate. November 13th turned into Callahan’s highest scoring day. 27 confirmed kills. It wasn’t raw efficiency. It was collapse. Callahan’s deception system reached critical mass.

So many cans, so many angles, so many signal events that the Japanese couldn’t distinguish real threats from illusions. When defensive officers saw multiple flash sequences at once, they assumed an assault was brewing. They repositioned men across exposed terrain. They checked flanks. They attempted to coordinate counter measures. Every movement they made was visible.

Every officer who stepped out to verify troop placement became a silhouette in Callahan’s scope. Captured diaries later revealed the psychological effect. Light appears from nowhere. Men go to investigate and never return. In few mark in this game, officers forbid investigation, but orders require observation. End. I no longer trust my eyes. Here’s locks.

Once an army loses trust in its own senses, it loses the battlefield. Callahan didn’t destroy their manpower on day four. He destroyed their confidence. On November 15th, heavy clouds rolled in. No sunlight meant no reflections. The soup can system should have died. Instead, Callahan revealed the most underestimated part of his mind. He hadn’t built a weapon around light. He’d built a weapon around compulsion.

If light could trigger curiosity, so could sound. He hung empty ammunition cans from branches, filled them with pebbles, and rigged strings to shake them from distances. Soft rattles, short taps, a clatter that suggested movement or equipment. By noon, the Japanese were back in the same trap.

Patrols creeping out, observers exposing themselves, officers trying to restore order, and Callahan waiting at angles no one thought to check. Nine more kills. The final shot came at 1545. A Japanese officer consulting a map during a moment of confusion. One bullet, one collapse, one more fracture in the chain of command. When Callahan withdrew at 16, his five days were up.

112 confirmed kills, nearly 100 independently verified, a battalion’s intelligence network shattered, and an entire sector paralyzed by stimuli made from garbage. Callahan hadn’t just used trash. He had used something far more dangerous. The enemy’s training, the enemy’s habits, the enemy’s instincts.

And for 5 days, he turned all three against them. When the shooting stopped, the Japanese 6th division wasn’t defeated in the traditional sense. They hadn’t been overrun, outgunned, or outmaneuvered. They had been blinded. And in warfare, losing your eyes is worse than losing your soldiers. For weeks before Callahan arrived, the Japanese had fought with confidence.

Their snipers dominated treetops. Their observers fed accurate reports. Their officers trusted what they saw. It wasn’t arrogance. It was structure. Doctrine. Routine. Callahan shattered that routine in 5 days. The Japanese didn’t understand the mechanism, but they felt the consequences immediately. Patrols disappeared, investigating harmless flashes.

Officers died, stepping out to verify fake signals. Observation posts went silent. Communication chains fragmented under fear and confusion. None of this required destroying their firepower. Callahan destroyed their decision-making system. This is the part most histories never emphasize. Armies do not fall apart when they lose men. They fall apart when they lose certainty. And certainty was the first casualty of Callahan’s operation.

After the war, analysts reviewing Japanese field logs noticed the same pattern repeating. Light phenomena observed. Reconnaissance ordered. Reconnaissance team eliminated. Followup restricted. Information gap widens. Officers forced to act without reliable data. By the end of day four, Japanese commanders had almost no trustworthy eyes on the front line.

Their reports became vague, fragmented, and sometimes contradictory. What Callahan achieved wasn’t tactical dominance. It wasformational starvation. A modern intelligence officer would call this a sensor kill chain. End quote. Callahan discovered it intuitively decades before the term existed.

Every time a Japanese observer tried to answer a question, Callahan made sure the answer cost them a life. Eventually, no one dared ask questions at all. And an army that stops asking questions stops functioning. Captured diaries from that week reveal something extraordinary. Not fear, not panic, but something much worse. Doubt. Soldiers doubted their eyes. Officers doubted their judgment.

Units doubted their own doctrine. One entry read, “The Americans use light to lure us. We cannot know which signals are traps. I am afraid not of death, but of misjudgment. We have not. That sentence says everything. War rarely destroys people with firepower. War destroys people with choices they no longer trust.

Callahan’s trick didn’t just kill soldiers. It created a battlefield where curiosity was punished, discipline was punished, initiative was punished, and hesitation was punished. There was no right answer, only uncertainty. This is why the Japanese response became increasingly irrational.

Pulling sentries back, then pushing them forward, forbidding investigation, then demanding it, reducing exposure, then exposing officers instead. The commander’s diary reflected this frustration. Enemy employs methods we cannot categorize. We cannot understand the purpose of the light. Our men fear illusions. We operate blind. F. And first when a battalion starts describing its enemy as the invisible one or the demon, it means their doctrine has collapsed. They are no longer fighting a person. They are fighting a phenomenon.

And no army in history has ever been trained for that. The Japanese weren’t incompetent. Their doctrine simply didn’t account for the possibility that an American sniper would weaponize deception, misdirection, false signatures, and psychological triggers. Japanese counter sniper methods relied on spotting muzzle flashes, tracking movement, reading trails, or detecting camouflaged positions.

Callahan gave them no movement, not trails, no patterns, no logic. He created stimuli that were impossible to categorize. Not a threat, not harmless, not a signal, not random, not attack, not retreat. In doctrinal terms, he created a non-classifiable stimulus, a type of battlefield information soldiers are mentally unprepared to process.

When humans can’t classify information, they default to instinct. And instinct is precisely what Callahan manipulated. For 5 days, the Japanese didn’t lose a tactical fight. They lost the philosophical foundation of their battlefield understanding. Their rule book stopped working. The world stopped making sense.

And no one fights well in a world they no longer understand. By the end of the operation, the Japanese still didn’t know what had happened. They knew men had died. They knew positions had been compromised. They knew their decision loop had been hijacked. But they didn’t know the truth. They hadn’t been defeated by a rifle. They had been defeated by a rule they didn’t know they were following.

Investigate anything unusual is Callahan didn’t break that rule. He exploited it over and over with total precision. And that’s the real lesson buried beneath the kill count. He didn’t overpower the Japanese. He made their own discipline fatal.

When Callahan walked off the line on November 15th, he didn’t look like a man who had just executed one of the most effective sniper operations of the Pacific War. He looked exhausted, hands shaking, voice flat, eyes unfocused. 5 days of perfect patience, 5 days of decisions that allowed no mistakes. 5 days of watching men walk into traps he had designed, knowing exactly how each one would end.

That kind of mental pressure doesn’t disappear when you step off the line. It lingers. Medical officers recorded what they politely called combat exhaustion, right? Not the shaking, shouting kind, the quiet kind, the kind where the silence feels heavier than the gunfire. Callahan wasn’t proud. He wasn’t triumphant. He was simply aware of what most outsiders never understand.

Every good idea in war has a human cost, even for the man who creates it. While recovering in the rear, Callahan spent two weeks doing something he’d never done before. He slowed down for the first time in days. He wasn’t calculating angles. He wasn’t predicting reactions. He wasn’t engineering exposure cycles. But his mind didn’t stop working. It replayed everything.

The flashes, the shots, the decisions, trying to make sense of what he’d done. He didn’t question the mission. He questioned the feeling that came after the realization that he’d weaponized curiosity. a basic human instinct and watched it kill over a hundred men who never understood what they were walking into.

In one quiet interview decades later, he summarized it simply. I wasn’t proud of killing them. I was proud we survived. Sometimes that’s the only victory you get. So Callahan never confused necessity with glory. That’s what made him dangerous on the battlefield and effective in the classroom. By January 1944, the Marine Corps made a decision that changed the rest of his life. Callahan would not return to frontline sniper duty.

He had proven everything a sniper could prove and more. Now the core wanted something different from him, his thinking. He was reassigned to Camp Pendleton as an instructor. Not because they wanted to honor him, but because they needed the next generation of snipers to understand what he had discovered. That a rifle is only one part of the job.

That psychology is the real battlefield. That a good shot is useful, but a good mind is transformative. Callahan accepted the transfer without protest. He knew something the core had begun to understand. He wasn’t a better killer than other snipers. He was a better problem solver.

When Callahan walked into a sniper classroom for the first time, he did something almost no instructor did in 1 944. He erased the firing diagram on the board. Then he wrote a sentence, his own version of Henderson’s doctrine. The enemy doesn’t fear your rifle. He fears not knowing what you are. Oh, students expected lectures on wind calls, shooting positions, camouflage.

He taught those, but he didn’t start with them. He started with questions. What does the enemy need to see? What can he not afford to ignore? What behavior can you trigger without revealing yourself? What decision do you want him to make? Most recruits had never heard sniper work framed like that. To them, the job was marksmanship.

To Callahan, marksmanship was a consequence, not a purpose. He explained that the Bugganville operation wasn’t about cans or sunlight or clever tricks. It was about redefining the enemy’s perception. If the enemy interprets the battlefield incorrectly, he defeats himself. Callahan wanted students to understand the truth that shaped his 5 days on Buganville. A sniper doesn’t win by being unseen.

He wins by making the enemy see the wrong thing. Over the next two years, Callahan trained more than 400 snipers. His influence spread quietly through the force. Teams began experimenting with dummy signals. Deception positions became standard. Intelligence units, integrated false signature training, counter sniper doctrine shifted from find the shooter to control the shooter’s decisions.

Bes said, Callahan didn’t preach heroics. He didn’t talk about kill counts. He talked about thinking. And that’s where his real legacy began. Not in Bugganville’s jungle, but in classroom chalk dust and quiet field exercises. Students remembered him for one phrase he repeated constantly. Creativity keeps you alive. Convention gets you killed. 80. He meant it literally.

He had lived it. And his students would carry it into battles he would never see. Callahan survived the war physically unscathed, yet forever shaped by what he’d done. In Montana, he returned to teaching high school science, coaching, problem solving workshops.

Students never suspected that their calm, patient teacher once designed the most effective sniper deception operation of the Pacific War. He didn’t talk about kills. He talked about ideas. He never glorified the soup can trick. He explained the principle behind it. You don’t beat a strong enemy by being stronger. You beat him by making him think incorrectly.

Even in civilian life, he taught the same lesson the battlefield taught him. The mind is always the decisive terrain. History tends to reward spectacle. Big offensives, tanks, bombardments, flag raising moments. Quiet ideas rarely make it into the headlines. That’s why most people today don’t know the truth about Buganville.

that one Marine sergeant crippled an entire Japanese battalion’s intelligence network with garbage psychology and unconventional thinking. But within military doctrine, the story never disappeared. It evolved. Callahan’s report was copied, reprinted, dissected, and ultimately absorbed into what the modern military now calls deception operations and false signature warfare.

the idea that controlling the enemy’s perception is more decisive than controlling territory. If the enemy sees incorrectly, the enemy fights incorrectly. Every modern doctrine that manipulates radar signatures, spoofed communications, distraction techniques, or information warfare owes something to the same principle Callahan discovered with a soup can.

Force the enemy to respond to something that isn’t real. Then exploit the response. simple, obvious, deadly, and in 1943, revolutionary. The most compelling evidence of Callahan’s legacy didn’t come from Americans. It came from the Japanese themselves. Captured manuals from 1,944 added new doctrines. Do not investigate light anomalies.

If avoid exposure during verification of signals, Barah says assume unknown stimuli or enemy deception. It was right. These pages didn’t exist before Bugganville. They existed because of Buganville. You know, an idea has changed warfare when the enemy rewrites its training to defend against it. Callahan didn’t just disrupt a battalion.

He forced a foreign army to reshape its doctrine. For decades, the story, when it was told at all, focused on numbers. 112 kills, 5 days, soup cans, improvisation. It made Callahan sound like a gifted marksman with a clever gimmick. But that version misses the point. The real significance wasn’t the kill count.

It was the conceptual shift from shooting enemies to shaping enemy choices, from stealth to misdirection, from reacting to danger to manufacturing it. Callahan didn’t outshoot the Japanese. He outthought them. That’s why the kill count was so high. Not because he fired quickly, but because he controlled when others exposed themselves. And that principle remains the backbone of modern warfare. From cyber deception to electronic spoofing to psychological operations.

The technology changed. The idea didn’t. Before he died, Callahan summarized his entire wartime experience in one line. I didn’t beat them at their game. I changed the game. Ass. That sentence is easy to admire. It’s harder to understand. Changing the game isn’t flashy. It’s not loud. It’s not celebrated. It’s quiet, lonely, mentally exhausting work.

The kind of work that rarely earns medals, but often changes outcomes. Callahan wasn’t a symbol of American firepower. He was a symbol of something deeper in the American military tradition. Decentralized initiative, trust in junior leaders, permission to think, the belief that solutions can come from anywhere, even from a can of soup. That spirit, not the cans, not the kills, is why the operation mattered.

If you’ve watched this story to the end, you now know something most people never learn. The Pacific War wasn’t shaped only by machines and manpower. It was shaped by moments when individuals refused to accept the limits of the battlefield. Callahan’s trick changed nothing in the grand map of the war, but it changed everything in one critical sector at one critical moment, and its doctrinal impact rippled far beyond Bugganville.

That’s the real secret hidden behind the simple, almost laughable image of a marine holding a soup can. Wars aren’t won by the strongest forces. They’re won by the forces that think differently first. And on Bugganville, for five extraordinary days, one young sergeant proved exactly that. Not with firepower, not with technology, but with imagination. The only weapon that has no countermeasure.

Today, if you walk through the National Museum of the Marine Corps in Virginia, you’ll see Callahan’s Springfield rifle resting quietly behind glass. Beside it sit three dented, rust eaten soup cans. No plaque can fully explain how those worthless objects once crippled a Japanese battalion’s battlefield vision. Visitors often pass without slowing down.

It doesn’t occur to them that a few scraps of metal once did something artillery and air support could not. But those cans aren’t displayed because they’re relics of a strange episode. They’re displayed because they represent a truth about war that people often forget. Battles are shaped by thinking far more than by weapons.

Sniper students still study Callahan today, not to copy the reflection trick, but to understand how he viewed the battlefield. He saw it not as terrain and targets, but as a network of human minds trying desperately to interpret what they saw. If you can influence how an enemy interprets the world, you gain an advantage no rifle can match.

What most people don’t know, and what even fewer appreciate is that Callahan never considered himself a genius. In every interview, every document he wrote, every moment he reflected on Bugganville, he said the same thing. I just looked at the problem differently. To him, those five days weren’t a miracle. They were logic. They were the result of refusing to accept that the only way to beat a master sniper was to shoot better than he could.

Instead, Callahan rewrote the rules. And that simplicity is precisely why the story matters. If victory required superhuman skill or superior equipment, it would be rare and unreproducible. But if victory comes from perspective, if it comes from asking questions no one else thinks to ask, then any soldier in any era can learn from it. That is Callahan’s true legacy.

Not the number 112, not the five brutal days, not the intelligence report that struggled to categorize what he had done. His legacy is the reminder that every system has a blind spot. And sometimes to find that blind spot, you don’t need a high-powered optic. You just need an empty soup can.

After the war, Callahan’s life folded back into the quiet rhythm of smalltown Montana. He taught high school, coached, mentored, and lived without ever hinting to his students that he once made a Japanese unit believe they were being hunted by demon light. When he passed away in 2003, the words marine sniper appeared only once in his obituary. But those who knew the history understood.

The quiet teacher had once dismantled an enemy’s confidence so thoroughly that they rewrote their doctrine because of him. And that is where the story truly ends, not in gunfire or medals, but in a simple truth. Callahan lived every day afterward. War changes, but thinking differently never goes out of date.

Technology evolves, weapons evolve, tactics evolve, but the fundamental principle he uncovered remains untouched. The side that wins is the side that forces the other to think wrong. Callahan’s innovation didn’t come from brilliance and marksmanship. It came from imagination applied to a deadly problem. He proved that ingenuity has no rank, no budget, no regulation.

It appears wherever a human being refuses to accept that the world must be understood the way everyone else understands it. And that is why 80 years later, those rusted soup cans remain behind glass. Not to memorialize death, but to honor creativity. Creativity that saved marines, crippled an enemy, and reshaped doctrine. Because in every conflict, there is one kind of power no enemy can predict.

The imagination of a person determined to survive.

News

CH2 90 Minutes That Ended the Luftwaffe – German Ace vs 800 P-51 Mustangs Over Berlin – March 1944

90 Minutes That Ended the Luftwaffe – German Ace vs 800 P-51 Mustangs Over Berlin – March 1944 March…

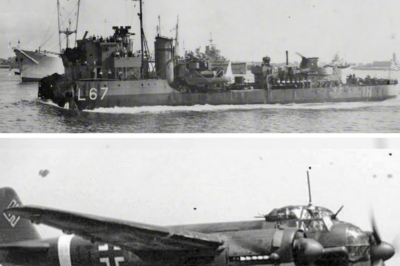

CH2 German Command Laughed at this Greek Destroyer — Then Their Convoys Got Annihilated

German Command Laughed at this Greek Destroyer — Then Their Convoys Got Annihilated You do not send obsolete…

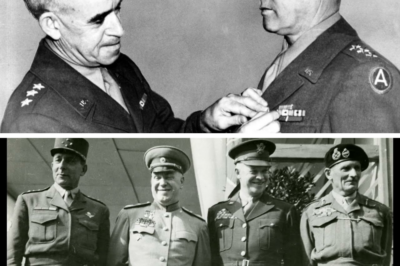

CH2 Why Bradley Refused To Enter Patton’s Field Tent — The Respect Insult

Why Bradley Refused To Enter Patton’s Field Tent — The Respect Insult The autumn rain hammered against the canvas…

CH2 Germans Couldn’t Stop This Tiny Destroyer — Until He Smashed Into a Cruiser 10 Times His Size

Germans Couldn’t Stop This Tiny Destroyer — Until He Smashed Into a Cruiser 10 Times His Size At…

CH2 When a Canadian Crew Heard Crying in the Snow – And Saved 18 German Children From Freezing to Death

When a Canadian Crew Heard Crying in the Snow – And Saved 18 German Children From Freezing to Death …

CH2 They Mocked His “Pistol Only Crawl” — Until He Took Out a Machine Gun Crew on D-Day

They Mocked His “Pistol Only Crawl” — Until This Brooklyn Soldier Took Out a Machine Gun Crew on D-Day And…

End of content

No more pages to load