The Secret Weapon the U.S. Navy Hid on PT Boats — And Japan Never Saw It Coming

October 15th, 1943. The waters off Vella Lavella, Solomon Islands, were black as oil and still as glass. Only the low rumble of twin Packard engines broke the silence, vibrating through the wooden hull of PT-219 as Lieutenant Commander Marcus “Mad Dog” Sullivan gripped the wheel, his gloved hands slick with sweat despite the night air. The sky was clouded, moonlight fractured by drifting smoke from distant naval gunfire. Searchlights from Japanese destroyers swept across the water in wide, white arcs, slicing through the darkness like blades. Each beam sent a shimmer across the rippled surface, chasing ghosts — American patrol boats that had haunted Imperial convoys for weeks, striking fast and vanishing before the enemy could react.

But tonight was different.

Somewhere out there, among those tiny silhouettes darting through the Pacific shadows, was something the Japanese Navy had never seen — and would never understand until it was too late.

PT-219 looked like every other patrol torpedo boat: 80 feet long, narrow hull, twin torpedo racks gleaming faintly under starlight, its crew crouched low behind the gunwales, watching, waiting. Yet beneath its forward deck, hidden under a reinforced false cover, lay a weapon that could change the balance of naval warfare in the Pacific. Sullivan’s crew called it the “surprise package.” The men aboard the Japanese destroyers who would soon meet it called it something else — their final mistake.

The weapon had no official name, no record in the Navy’s public documentation, and no mention in the maintenance logs that followed each boat from New Orleans to the South Pacific. It was, officially, a non-existent project. Unofficially, it was the deadliest upgrade the Navy had ever approved for a vessel that small: a concealed 40mm Bofors anti-aircraft cannon — the same gun used on cruisers and destroyers — mounted secretly beneath the deck of twelve modified PT boats operating out of Tulagi.

When raised, it could unleash over 120 explosive rounds per minute, accurate to more than two miles, capable of tearing through the thin plating of a destroyer’s bridge or shredding an entire deck gun crew in seconds. It was the great equalizer, and it turned fragile wooden torpedo boats into something the Japanese weren’t prepared to fight — predators disguised as prey.

Lieutenant Commander Sullivan had spent weeks preparing for this night. The Japanese convoys had become bolder, running supplies through the Solomons under the cover of darkness, shielded by destroyers whose captains considered the PT boats little more than an annoyance — mosquitoes to be swatted aside with a burst of 5-inch shells. What those captains didn’t know was that the mosquitoes had learned to bite back.

As PT-219 idled among the mangroves, Sullivan raised his binoculars. Three enemy destroyers approached from the northwest, cutting a steady path through the darkness. Their wakes shimmered faintly in the phosphorescent water, silver trails that gave away their approach. He could see their superstructures outlined against the faint glow of the horizon — tall, sleek, confident shapes that moved with predatory grace. The Japanese had hunted his boats for weeks. Now the hunter was about to become the hunted.

Below deck, the engine room was a furnace of noise and motion. Machinist’s Mate First Class Roberto Vasquez crouched between the roaring Packards, his face streaked with oil and sweat, watching the gauges tremble. He had been working nonstop for six hours, fine-tuning the engines for the night’s run, knowing one misfire could mean the difference between a clean escape and a fiery death. Near his feet, hidden beneath a false bulkhead, lay the steel-encased ammunition boxes for the gun above — each round weighing nearly two pounds, each capable of punching through armor that no PT boat was ever meant to challenge.

The idea of mounting a destroyer’s gun on a plywood patrol boat had been born six months earlier, in a drafty corner of the Higgins Industries shipyard in New Orleans. The man behind it was Commander Harrison Webb, a quiet, analytical officer from Annapolis who had spent more time reading casualty reports than sleeping. Webb’s face carried the weariness of someone who had watched too many young crews burn to death in the fragile boats they’d been given. He’d seen the pattern: Japanese destroyers sweeping through the dark, PT boats darting in, firing torpedoes that too often missed, then dying under a hail of gunfire.

The PT boats were fast — but not faster than a shell. They were agile — but not agile enough to outrun radar. And they were brave — always brave — but bravery was no match for steel and 5-inch guns.

Webb had walked into Andrew Jackson Higgins’s office one humid April afternoon carrying a folder filled with after-action reports from the Solomons. He tossed it onto Higgins’s cluttered desk, where it landed among blueprints and coffee rings. The reports were grim: more than a dozen boats lost in six weeks, hundreds of men dead, entire squadrons reduced to splinters and oil slicks. Higgins, the short, explosive boat builder whose landing craft had already changed the course of the war, read them in silence.

“So what do you want from me?” Higgins had asked finally, his gravelly voice half amusement, half challenge.

“I want to put a forty-millimeter gun on one of your boats,” Webb replied.

Higgins had laughed, a short, barking sound that filled the room. “You put that gun on a PT boat, Commander, and the first time it fires, it’ll blow a hole through the deck big enough to fit a jeep.”

“Then make the deck stronger,” Webb said.

That single line started a project so secret it never appeared in Navy shipbuilding records. Higgins cleared out one corner of his factory, posted armed guards, and brought in a handful of trusted engineers. Among them was Lieutenant Patricia Reynolds, one of the Navy’s first female ordnance specialists, a young engineer with a reputation for seeing patterns others missed. She had been analyzing Japanese naval reports for months, studying how enemy captains described PT boats in their logs. The Japanese called them “mosquito craft”— annoying, fast, but ultimately harmless. That assumption, Reynolds realized, was the Navy’s greatest weapon.

If the PT boats could remain visually identical but carry the firepower of a small destroyer, they could exploit that overconfidence. Japanese captains would close in for the kill, unaware that the Americans were waiting for the perfect range — the range where surprise became slaughter.

The challenges were immense. The Bofors 40mm gun weighed nearly three tons, far more than a PT boat was designed to carry. Its recoil could tear a hull apart if mounted directly. The ammunition was bulky, the loading mechanisms delicate, and the boats themselves already cramped with torpedoes, engines, and fuel. But Higgins’s engineers found solutions. They built a new internal frame using reinforced steel beams that distributed the recoil through the entire hull. They designed a retractable hydraulic lift that could raise the gun into firing position in sixty seconds and conceal it completely beneath a watertight deck plate when not in use. Ammunition was hidden inside false fuel compartments, accessible through secret hatches only the gunners knew about.

Testing took place under tight security in the murky waters of Lake Pontchartrain. Officially, the boats were part of a “torpedo propulsion trial.” The gun crews were volunteers who signed non-disclosure oaths and worked under codenames. Night after night, they tested the weapon in silence, firing special low-flash rounds to hide their position. The gun’s thunder echoed across the lake, but even nearby Navy pilots believed they were hearing torpedo detonations.

The results stunned everyone involved. The modified boats could engage moving targets at four thousand yards with pinpoint accuracy. The recoil, once feared to be catastrophic, proved manageable thanks to the reinforced structure. The new power configuration even improved top speed slightly, giving the boats a performance edge over their standard counterparts.

When the first twelve boats were completed, they were quietly shipped to the Pacific, reclassified under false serial numbers. Only Admiral Chester Nimitz and a handful of senior staff knew the truth. Officially, they were standard Mark VIII PT boats. Unofficially, they were something else entirely — experimental hunter-killers that could turn a Japanese destroyer’s advantage into its downfall.

By the time Sullivan received his orders to report to Tulagi, he had already earned his nickname. “Mad Dog” wasn’t a compliment at first — it was a warning. He’d attacked enemy convoys in the dead of night, weaving between destroyers, firing torpedoes at suicidal ranges, laughing over the roar of gunfire. He’d seen his men die, seen boats burn to ash, but he’d never lost the taste for the fight.

When he arrived at the docks and saw PT-219 for the first time, he thought it looked ordinary. Too ordinary. Then the chief engineer showed him the hidden lift under the forward deck, and Sullivan’s smile returned — the same wild grin that had earned him his callsign.

Now, in the black waters off Vella Lavella, Sullivan lowered his binoculars and watched the destroyers creep closer. The moon broke through the clouds, lighting the sea in pale silver. Somewhere beneath his feet, concealed beneath the deck plates, the hydraulic system waited, ready to lift the weapon no Japanese sailor even knew existed.

He leaned toward his radio operator, voice low, steady, almost calm. “Engines at half. Keep her bow toward the lead ship.”

A bead of sweat slid down his temple as he gripped the wheel tighter. The enemy lights swung closer. The night air thickened with tension. Every man aboard PT-219 knew what was hidden beneath their feet — and what would happen when it finally rose from the deck.

Sullivan’s eyes stayed fixed on the horizon, the destroyers closing, unaware. The trap was set. The sea was holding its breath. And the secret weapon, still locked beneath steel and secrecy, waited for his command.

Continue below

October 15th, 1943. The waters of Vela Lavella, Solomon Islands. Lieutenant Commander Marcus Mad Dog Sullivan gripped the wheel of PT219 as Japanese search lights swept across the Black Pacific waters. Their beams hunting for the American patrol boats that had been terrorizing enemy convoys for weeks. What Admiral Tanaka Kasuk and his destroyer captains didn’t know was that the seemingly defenseless torpedo boats they’d been chasing carried a secret weapon that would revolutionize naval warfare in the Pacific.

The 40mm bow force anti-aircraft gun normally mounted on cruisers and destroyers had been secretly installed on 12 experimental PT boats operating out of Tagi.

These boats looked identical to standard PT boats from any distance, but they packed the firepower to engage destroyers in direct combat. The Japanese Navy had no idea they were hunting predators disguised as prey. As PT2 Wein’s engines rumbled at idle speed, Sullivan watched through his binoculars as three Japanese destroyers approached in formation.

The enemy ships moved with the confidence of hunters pursuing wounded game, never suspecting that the Americans had turned the tables. In the engine room below, machinists made first class Roberto Vasquez had spent the last 6 hours fine-tuning the boat’s twin Packard engines while keeping one eye on the carefully concealed bow for mount that would soon announce America’s latest tactical surprise to the Imperial Japanese Navy.

The story of how American PT boats gained their secret teeth began 6 months earlier in the human workshops of the Higgins Industry shipyard in New Orleans, Louisiana. Andrew Jackson Higgins, the canankerous boat builder whose landing craft would carry Allied forces to victory across the Pacific, had received an unusual visit from a small group of Navy officers led by Commander Harrison Webb, a soft-spoken Anapopoulos graduate with calloused hands and the intense eyes of someone who had seen too many good men die in inadequate equipment. Webb carried with him a folder of afteraction reports that painted a

disturbing picture of PTBO operations in the Solomon Islands. The boats were fast, maneuverable, and deadly against enemy transports. But when caught by Japanese destroyers or cruisers, they became helpless targets. Their machine guns and 20mm cannons could damage super structures and kill personnel, but couldn’t penetrate the armor of warships designed to withstand naval gunfire.

Too many brave crews had died trying to escape superior firepower with nothing but speed and prayer. The solution came from an unexpected source. Lieutenant Patricia Reynolds, one of the Navy’s first female ordinance engineers, had been studying captured Japanese damage reports from destroyer attacks on PT boats.

Working late nights in a converted warehouse office in San Diego, surrounded by technical manuals and empty coffee cups, she noticed something the combat reports had missed. Japanese destroyer captains consistently described PTBot attacks as mosquito stings that forced them to break off convoy escorts but never cause serious damage.

Reynolds realized that Japanese tactical doctrine assumed PT boats were purely torpedo platforms with minimal defensive armament. Destroyer captains would close to medium range, confident their armor could deflect anything the Americans could throw at them. This tactical blind spot created an opportunity. If PT boats could mount heavier guns while maintaining their appearance as lightly armed torpedo boats, they could achieve complete tactical surprise at close range.

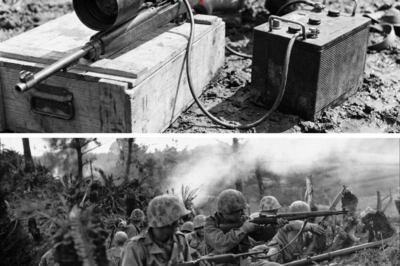

The technical challenges seemed insurmountable. The Swedish’s designed 40 mm per bow force gun weighed nearly 3 tons and generated tremendous recoil forces that could tear apart a PT boat’s lightweight hull. The gun’s ammunition requirements meant reducing torpedo loads, compromising the boat’s primary mission.

Most critically, the installation had to be completely concealed from aerial reconnaissance while remaining operationally ready for immediate action. Higgins detected the problem with characteristic determination. His engineers, working in a heavily guarded section of the New Orleans facility, developed a revolutionary concealment system.

The bow force gun was mounted on a hydraulic platform that could be raised and lowered within 60 seconds. When retracted, a speciallyesed deck plate covered the opening, making the installation invisible from any angle. The ammunition storage was integrated into the boat’s fuel compartments, hidden behind false bulkheads that would pass even close inspection.

The recoil problem required completely rebuilding the PTBO’s internal structure. Higgins’s team installed a network of steel reinforcement beams that distributed the gun’s firing stresses throughout the hull. The modification added only 800 elabo to the boat’s displacement while providing the structural integrity needed for sustained gunfire.

To maintain the boat’s speed advantage, they upgraded the engines and redesigned the propeller configuration, actually improving performance over standard PT boats. Testing began in the brackish waters of Lake Poncha Train under conditions of absolute secrecy.

Navy pilots flying overhead were told they were observing experimental torpedo systems. The boats conducted nightfiring exercises using specially modified ammunition that produced minimal muzzle flash. Even the gun crews were recruited from volunteers who signed additional security oaths and underwent extensive background investigations.

Commander Webb personally oversaw the trials, often spending 18 hours aboard the test boats as they refined firing procedures and tactics. The results exceeded every expectation. The concealed bow force could engage targets at ranges up to 4,000 yd with devastating accuracy. More importantly, the psychological impact on enemy crews was overwhelming.

Japanese destroyer captains approaching what appeared to be a helpless PT boat suddenly found themselves under accurate heavy gunfire from an opponent they had assumed was defenseless. The first production boats emerged from Higgins Industries in late July 1943, designated as PT215 through PT226. Officially, they were listed as standard Mark 8 PT boats with minor equipment modifications.

Their actual specifications remained classified at the highest levels known only to Admiral Chester Nymphs and a handful of Pacific Fleet Staff officers. Even the boat’s commanding officers received their briefings only after arriving at their forward operating base. Tulagi Harbor became the secret headquarters for what would be designated task unit 73, though no such unit appeared on any official Navy organization charts.

The 12 experimental PT boats operated under the cover designation Special Operations Development Group, supposedly testing new torpedo systems and recognition equipment. Their actual mission was to engage Japanese surface forces using tactics that exploited the enemy’s assumptions about PTBO capabilities.

Lieutenant Commander Sullivan had commanded PT boats since the early days of the Guadal Canal campaign, earning his nickname Mad Dog for his aggressive attacks on enemy convoys despite overwhelming odds.

It mean when he received orders to report to Tulagi for special assignment, he expected another suicide mission against heavily defended harbors. Instead, he found himself looking at what appeared to be a standard PT boat with one crucial difference that would change everything he understood about naval combat.

Chief Petty Officer William Tank Morrison, a grizzled veteran of pre-war Pacific patrols, conducted Sullivan’s orientation aboard PT219. Morrison had been handpicked for the program based on his experience with naval gunnery and his reputation for maintaining absolute discretion about classified operations.

As he demonstrated the Bowfor’s installation rising smoothly from its concealed position, Sullivan realized he was looking at a weapon system that could fundamentally alter the balance of power in night surface actions. The gun itself was a masterpiece of Swedish engineering. Adapted by American manufacturers for naval use, its twin barrels could fire 120 rounds per minute of 40 mters high explosive shells capable of penetrating destroyer armor at combat ranges.

The shells contained enough explosive power to disable critical systems, start fires, and kill personnel in exposed positions. More importantly, the gun’s rapid fire capability meant a single PT boat could deliver the equivalent firepower of a destroyer secondary battery in a sustained engagement. Training the gun crews required developing entirely new tactical doctrines.

Traditional PTBO operations emphasized hit and run attacks using speed and darkness for protection. The Bowfor’s boats could conduct sustained engagements, but success depended on achieving complete surprise in the opening moments of combat. Once the enemy realized they were facing heavy guns, Japanese destroyers would respond with their main batteries, creating a firepower contest, the PT boats couldn’t win.

Sullivan’s crew spent weeks practicing the precise choreography required for effective bow force operations. The boat had to approach targets while maintaining the appearance of a standard PT boat, often allowing enemy ships to close to ranges that would be suicidal for conventional tactics.

At the critical moment, the gun would rise, acquire targets, and deliver devastating fire before the enemy could respond effectively. The timing had to be perfect, or the boat would be destroyed by return fire from multiple Japanese ships. The psychological preparation was equally challenging. PTB boat crews were accustomed to being outgunned by virtually every enemy ship they encountered.

Learning to engage destroyers in direct combat required overcoming months of tactical conditioning that emphasized evasion over confrontation. Sullivan’s gunners had to develop the confidence to stand exposed on deck, serving a weapon that made them obvious targets while destroyer shells exploded around their position. The boat’s first operational deployment came during the Japanese evacuation of Colombara in late August 1943.

Admiral Tanaka’s destroyer force had been conducting nightly runs to evacuate troops from the island, using their superior firepower to drive off American PTBOT attacks. Intelligence reports indicated the Japanese had developed effective counter measures against torpedo attacks using search lights and concentrated gunfire to suppress PT boat operations.

Sullivan’s division of four bow force boats received orders to intercept the evacuation convoy on the night of August 27th. The operation would test whether the secret weapons could achieve tactical surprise against experienced Japanese destroyer crews operating in familiar waters. If the mission succeeded, it would validate the entire program.

If it failed, the lost boats would be listed as conventional PT boat casualties and the program would be quietly terminated. The weather conditions were ideal for PTBOT operations. Heavy cloud cover eliminated moonlight while providing adequate visibility for surface navigation.

A light wind from the southeast created sufficient sea state to mask the boat’s wakes while avoiding the rough conditions that would complicate gunnery. Most importantly, the weather prevented effective aerial recognition, ensuring the Japanese convoy would rely entirely on surface lookouts for threat detection. PT219 led the formation as they departed to Laji just after sunset, running northwest toward the intercept position calculated by intelligence analysts.

The other boats followed at $500 intervals, maintaining radio silence while navigating by compass and dead reckoning. Their Bowers guns remained concealed beneath specially designed deck plates that had been painted and weathered to match the boat’s overall appearance.

As they approached the intercept area, Sullivan could see the distant glow of fires on Kol Bangara, where Japanese engineers were destroying supplies they couldn’t evacuate. The evacuation convoy would be heavily loaded with troops and equipment, making the destroyers less maneuverable, but more determined to avoid engagement.

Japanese doctrine emphasized preserving the evacuation capability over engaging enemy forces, giving the PTBOS a tactical advantage if they could avoid premature detection. The radar operator aboard the lead destroyer Hamacaz detected the approaching PT boats at 0 to 37 hours range approximately 8,000 WB weight.

Captain Motoy Katsumi commanding the escort force immediately ordered his ships to increase speed and prepare for torpedo attack. His tactical manual specified that PT boats would launch torpedoes at maximum range, approximately 3,000 weaved, then retire at high speed while laying smoke screens.

The standard Japanese response was to illuminate the attacking boats with search lights while delivering suppressive fire with secondary armament. What Captain Moy didn’t know was that Sullivan’s boats carried no torpedoes. Their weapons load consisted entirely of 40 mm ammunition and enough fuel for extended high-speed operations. The boat’s apparent approach toward torpedo launch range was actually a carefully planned deception designed to draw the Japanese destroyers into gun range while maintaining the element of surprise.

At 3,000, exactly when Japanese doctrine predicted torpedo launch, the PT boats made an unexpected maneuver. Instead of turning away to retire, they continued closing the range while reducing speed to improve gunnery stability. Captain Moy, watching from Hamacaza’s bridge, initially interpreted this as a navigation error or mechanical failure.

PT boats never willingly closed to gun range against destroyers. The American boats appeared to be delivering themselves for destruction. Sullivan watched the Japanese search lights sweep toward his formation as PT219 reached the predetermined engagement range of 1500 Waldo Rulfrey.

At this distance, the bow force guns could achieve devastating accuracy against destroyer super structures, while the PT boats remain small enough targets to complicate Japanese fire control. The moment had arrived to reveal America’s secret weapon, to an enemy who had no idea what was about to hit them. The hydraulic wine of the Bowfor’s mount rising from its concealed position was barely audible over the engine’s rumble, but to Sullivan, it sounded like thunder rolling across the Pacific.

In 30 seconds, the Imperial Japanese Navy would discover that the helpless torpedo boats they had been hunting carried the firepower to sink destroyers. The tactical surprise would be complete, devastating, and absolutely crucial to changing the balance of power in the Solomon Islands campaign. Chief Morrison’s voice crackled through the intercom as the gun reached firing position.

Both ready, target designated, range 1500 YD. The moment of truth had arrived. Everything depended on the next 60 seconds of combat. The Japanese destroyers were closing rapidly. Confident they were engaging conventional PT boats with machine guns and 20mm cannons. They were about to learn that American naval innovation had turned their tactical assumptions into a death trap.

The secret that Admiral Tanaka’s destroyer crews were about to discover would revolutionize PTB operations throughout the Pacific. But first, those 12 experimental boats had to survive their baptism of fire against an enemy force that outweighed them 10 to1.

The mathematics of naval combat were about to be rewritten by Swedish guns on American boats operated by crews who understood that surprise was their only advantage against superior firepower. In the engine room of PT219, machinist mate Vasquez felt the boat’s vibration change as the engines were throttled back for firing. Above him, the bow force gun was tracking toward targets that had no idea they were about to face weapons they believed impossible.

The Japanese Navy’s confidence in their tactical superiority over PT boats was about to be shattered by 40 miller of Swedish steel, delivering American determination at 200 feet per second. The story of how that confidence was destroyed and how 12 boats changed the course of the Pacific War was about to be written in tracer fire and exploding shells across the dark waters off Lavella.

The Imperial Japanese Navy had hunted PT boats for months, never realizing they were about to become the prey. The first shell from PT219’s Bowfor’s gun struck the destroyer Hamakaz’s forward superructure at Uru39 hours, sending a brilliant orange flash across the dark waters. Captain Moto Katsumi felt his ship shutter as the high explosive round detonated against the bridgewing, killing three lookouts instantly and showering the command deck with razor sharp metal fragments.

For a moment that seemed frozen in time, the Japanese captain stared in absolute disbelief at the source of the incoming fire. The small American boat that should have been armed with nothing more dangerous than machine guns was pouring 40 mm meter shells into his destroyer with the precision of a heavy cruiser.

The tactical manual Captain Mie had studied at the Naval War College contained no procedures for this scenario. PT boats were classified as torpedo craft with minimal defensive armament incapable of engaging destroyers in direct combat. Yet the evidence was exploding around him as shell after shell crashed into Hamaka’s super rupture.

Each impact sending cascades of sparks and debris across his deck. The impossible was happening and Japanese doctrine had no answer for weapons that weren’t supposed to exist. Chief Morrison’s gun crew aboard PT219 worked with mechanical precision despite the chaos erupting around them. The bow for guns twin barrels hammered out rounds at a sustained rate of fire that surprised even Sullivan who had witnessed every test firing during the weapons trials.

The Swedish’s automatic loading system functioned flawlessly under combat conditions, feeding 40 militus shells into the firing chambers faster than the gun crew could track new targets. Each round carried enough explosive power to penetrate destroyer plating and cause massive internal damage to critical systems.

The second destroyer in the Japanese formation, Yuki Kaz, attempted to bring her main battery to bear on the attacking PT boats, but her fire control radar had been calibrated for engaging large surface targets at extended ranges. The small, fast-moving American boats presented tracking problems that Japanese gunners had never encountered in their training exercises.

Commander Sato Hiroshi, Yuki Kaza’s captain, watched in growing frustration as his 5-in guns fired salvo after salvo at targets that seemed to dance between the shell splashes like deadly phantoms. What the Japanese destroyer captains couldn’t understand was that Sullivan’s boats were executing tactics specifically developed to exploit the limitations of destroyer fire control systems.

The PT boats operated at ranges where they were too close for effective radar tracking, but far enough away to avoid being overwhelmed by small caliber defensive weapons. This tactical sweet spot had been identified during extensive testing off Louisiana, where Navy gunnery experts had calculated the optimal engagement envelope for PT boats armed with medium caliber weapons.

The third destroyer, Shiranoui, managed to illuminate PT221 with her search light just as Lieutenant Davidson’s bow force gun came to bear on the Japanese ship’s bridge structure. The brilliant white beam that was supposed to blind the American gunners instead provided perfect target illumination for the Swedish weapon system.

Davidson’s crew had trained for exactly this scenario, using the enemy zone search lights to enhance their gunnery accuracy. The result was devastating. Six consecutive hits along Shiranui super rupture destroyed her primary fire control system and killed most of her bridge crew.

Commander Webb monitoring the engagement from his command post at Tagi received radio reports that seemed to defy everything he knew about naval combat. Four lightly armed patrol boats were engaging three Japanese destroyers in direct gunfire and winning.

The experimental bow force installation was performing beyond every optimistic projection, delivering firepower that was fundamentally changing the tactical balance in PTBO operations. More importantly, the Japanese appeared to be completely unprepared for this type of engagement. The psychological impact on Japanese crews was as devastating as the physical damage from the 40mm shells.

Seaman Firstclass Tanaka Yoshio serving as a lookout aboard Hamac would later describe the engagement in his diary as fighting ghosts that struck with the power of demons. The sudden appearance of heavy gunfire from boats that should have been helpless created a sense of unreality that paralyzed Japanese response procedures.

Officers and enlisted men alike struggled to comprehend an enemy that violated every assumption of American naval capabilities. Captain Moy attempted to coordinate his destroyer’s response using voice radio, but the tactical situation was deteriorating too rapidly for conventional command and control procedures. His ships were taking heavy damage from weapons they hadn’t expected to face.

Operated by crews who seemed to understand Japanese weaknesses better than the Japanese understood themselves, the American boats moved with a precision that suggested months of preparation for this specific engagement. PT223’s commander, Lieutenant Robert Chen, had positioned his boat to exploit the gap between Yuki Ka and Shiranoui when both destroyers turned to engage other targets.

Chen’s bow force crew had been waiting for exactly this opportunity, having studied Japanese destroyer tactics during their training period. When Yuki Cass’s stern became exposed during her turn, Chen’s gunners delivered 18 rounds into the destroyer’s engineering spaces, causing massive steam leaks that reduced her speed and maneuverability.

The damage reports flooding into the Japanese formation painted a picture of tactical disaster. Hamakaz had lost her forward fire control system and suffered significant casualties among her bridge personnel. Shiranoui was listing to starboard with major flooding in her forward compartments. Yuki Caz was operating on reduced power with her engineering plant damaged.

None of the Japanese ships had scored significant hits on the elusive American boats that continued to pour accurate fire into their formations. What Captain Motto couldn’t know was that the American boats were executing a carefully rehearsed battle plan that had been developed through months of analysis of Japanese destroyer tactics.

Navy intelligence officers had studied captured Japanese tactical manuals and identified specific weaknesses in their night combat procedures. The Bowfor’s boats had been positioned and maneuvered to exploit these weaknesses while maximizing the effectiveness of their concealed armament.

The turning point came when Hamacaz’s damage control teams managed to restore partial power to her main battery. Captain Motto ordered his remaining functional guns to target PT219. Recognizing that the lead American boat appeared to be coordinating the attack, three 5-in shells bracketed Sullivan’s position, sending towering columns of water crashing down on PT21’s deck.

For a moment, it appeared the Japanese destroyers might regain the initiative through concentrated firepower. Sullivan’s response demonstrated the tactical flexibility that made the bow force boats so effective. Instead of withdrawing from the engagement as conventional PTBBO doctrine would require, he ordered his boat to close the range even further.

While his gunners continued to hammer the Japanese destroyers, the Swedish weapon system proved capable of sustained fire even while the boat maneuvered at high speed through heavy shell splashes. This combination of mobility and firepower created tactical options that had never existed in previous PTB boat operations. The Japanese formation began to break apart as individual ships maneuvered independently to avoid the devastating 40 mm fire.

Shiranoui with her bridge crew dead and her steering damaged began a wide turn to starboard that exposed her entire port side to PT Duni’s bow force gun. Lieutenant Rodriguez’s crew delivered 23 hits along the destroyer’s waterline, causing catastrophic flooding that would eventually sink the ship. The sight of a Japanese destroyer going down under fire from PT boats created shock waves throughout the Imperial Navy that would influence tactical planning for the remainder of the war.

Commander Sato aboard Yukis made the decision that would save his ship, but confirm the tactical revolution the Americans had achieved. Recognizing that his destroyers couldn’t effectively engage targets that combined PTBO mobility with heavy gunfire power, he ordered withdrawal to the northwest at maximum speed.

The Japanese evacuation convoy was abandoned to its fate as the escort force fled from an enemy they couldn’t understand or counter. The engagement lasted 47 minutes from first contact to Japanese withdrawal. During that time, 12 PT boats armed with concealed bow force guns had defeated a Japanese destroyer force that outweighed them by more than 10 to one. The tactical implications were staggering.

American patrol boats could now engage Japanese surface forces on nearly equal terms. transforming the strategic balance in the Solomon Islands campaign. PT2119’s damage assessment revealed just how close the engagement had come to disaster. Japanese shells had passed within yards of the boat’s ammunition storage, and several compartments showed flooding from near misses, but the boat remained operational, her bowor’s gun undamaged, and her crew ready for additional engagements. The experimental weapon

system had passed its combat test with results that exceeded every projection. The Japanese never understood what had happened during the Veila engagement. Post battle reports filed by the surviving destroyer captains described PT boats armed with heavy caliber weapons of unknown type, but failed to identify the Bowfor’s guns or understand their tactical significance.

Japanese intelligence analysts working with incomplete and contradictory information concluded that the Americans had somehow mounted destroyer guns on enlarged PT boat halls. This fundamental misunderstanding of American capabilities would plague Japanese tactical planning. For months, destroyer captains became increasingly reluctant to engage PT boats, never knowing whether they would face conventional torpedo attacks or devastating gunfire from concealed heavy weapons.

The psychological impact was as important as the tactical advantage, creating uncertainty that paralyzed Japanese surface operations in contested waters. Admiral Tanaka, reviewing the reports from his destroyer commanders, recognized that something fundamental had changed in PTBO capabilities, but lacked the intelligence to understand exactly what the Americans had achieved.

His tactical staff developed new procedures for engaging PT boats that assumed heavy gun arament, but these procedures were based on speculation rather than accurate intelligence about American weapon systems. The success of the Bowforce boats created new operational possibilities that naval planners had never considered. PT boats could now serve as heavy scouts engaging enemy surface forces to determine their composition and intentions.

They could provide fire support for amphibious operations using their mobility to position heavy guns where they were most needed. Most importantly, they could contest Japanese control of strategic waterways that had previously been dominated by superior enemy firepower. Sullivan’s report to Commander Webb contained a single paragraph that summarized the tactical revolution they had achieved.

The enemy responds to PTBO attacks based on assumptions about our armament that are no longer accurate. This provides opportunities for engagement under conditions where we possess decisive advantages. Recommend immediate expansion of the program. The understated language concealed the reality that 12 boats had fundamentally altered the balance of naval power in the Pacific.

The Japanese evacuation of Kolangara proceeded without escort protection, allowing American forces to interdict supply runs and troop movements that had previously been protected by destroyer screens. The tactical success of the bow force boats created strategic opportunities that would influence the entire Solomon Islands campaign.

Enemy commanders could no longer assume their destroyers provided adequate protection against American patrol boats. Within weeks of the Veila Lavella engagement, Japanese destroyer captains throughout the Solomon Islands were reporting encounters with heavily armed PT boats that could engage them on equal terms.

The psychological impact spread far beyond the actual number of Bowfors boats in operation, creating an atmosphere of uncertainty that affected Japanese surface operations throughout the region. Admiral Tanaka, reviewing the reports from his destroyer commanders, recognized that something fundamental had changed in PTBO capabilities, but lacked the intelligence to understand exactly what the Americans had achieved.

His tactical staff developed new procedures for engaging PT boats that assumed heavy gun arament, but these procedures were based on speculation rather than accurate intelligence about American weapon systems. The success of the bow force boats created new operational possibilities that naval planners had never considered.

PT boats could now service heavy scouts, engaging enemy surface forces to determine their composition and intentions. They could provide fire support for amphibious operations using their mobility to position heavy guns where they were most needed. Most importantly, they could contest Japanese control of strategic waterways that had previously been dominated by superior enemy firepower.

Sullivan’s report to Commander Webb contained a single paragraph that summarized the tactical revolution they had achieved. The enemy responds to PTBBO attacks based on assumptions about our armament that are no longer accurate. This provides opportunities for engagement under conditions where we possess decisive advantages. Recommend immediate expansion of the program.

The understated language concealed the reality that 12 boats had fundamentally altered the balance of naval power in the Pacific. The Japanese evacuation of Kolangara proceeded without escort protection, allowing American forces to interdict supply runs and troop movements that had previously been protected by destroyer screens.

The tactical success of the Bowfor’s boats created strategic opportunities that would influence the entire Solomon Islands campaign. Enemy commanders could no longer assume their destroyers provided adequate protection against American patrol boats.

Within weeks of the Veila engagement, Japanese destroyer captains throughout the Solomon Islands were reporting encounters with heavily armed PT boats that could engage them on equal terms. The psychological impact spread far beyond the actual number of bow force boats in operation, creating an atmosphere of uncertainty that affected Japanese surface operations throughout the region.

Admiral Tanaka, reviewing the reports from his destroyer commanders, recognized that something fundamental had changed in PTBO capabilities, but lacked the intelligence to understand exactly what the Americans had achieved. His tactical staff developed new procedures for engaging PT boats that assumed heavy gun armament, but these procedures were based on speculation rather than accurate intelligence about American weapon systems.

The success of the Bowfor’s boats created new operational possibilities that naval planners had never considered. PT boats could now serve as heavy scouts engaging enemy surface forces to determine their composition and intentions. They could provide fire support for amphibious operations using their mobility to position heavy guns where they were most needed.

Most importantly, they could contest Japanese control of strategic waterways that had previously been dominated by superior enemy firepower. Sullivan’s report to Commander Webb contained a single paragraph that summarized the tactical revolution they had achieved.

The enemy responds to PT boat attacks based on assumptions about our armament that are no longer accurate. This provides opportunities for engagement under conditions where we possess decisive advantages. recommend immediate expansion of the program. The understated language concealed the reality that 12 boats had fundamentally altered the balance of naval power in the Pacific.

The Japanese evacuation of Kolangara proceeded without escort protection, allowing American forces to interdict supply runs and troop movements that had previously been protected by destroyer screens. the tactical success of the bow force.

News

CH2 They Said the Shot Was ‘Impossible’ — Until He Hit a German Tank 2.6 Miles Away

They Said the Shot Was ‘Impossible’ — Until He Hit a German Tank 2.6 Miles Away At 10:42 a.m….

CH2 Japanese Soldiers Were Terrified When U.S. Marines Used Quad-50s to Destroy Their Banzai Charges

Japanese Soldiers Were Terrified When U.S. Marines Used Quad-50s to Destroy Their Banzai Charges The morning of February 8th,…

CH2 What Japanese Admirals Said When American Carriers Crushed Them at Midway

What Japanese Admirals Said When American Carriers Crushed Them at Midway At 10:25 a.m. on June 4th, 1942, Admiral…

CH2 How a U.S. Sniper’s ‘Car Battery Trick’ Killed 150 Japanese in 7 Days and Saved His Brothers in Arms

How a U.S. Sniper’s ‘Car Battery Trick’ Killed 150 Japanese in 7 Days and Saved His Brothers in Arms …

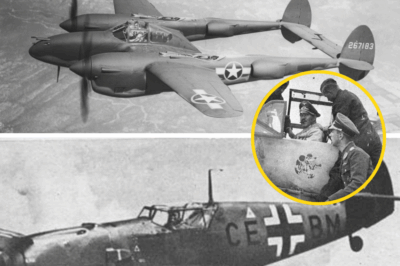

CH2 German Pilots Were Shocked When P-38 Lightning’s Twin Engines Outran Their Bf 109s

German Pilots Were Shocked When P-38 Lightning’s Twin Engines Outran Their Bf 109s The sky over Tunisia was pale…

CH2 When The Germans Saw The American Jeep Roaming On D-Day – Their Reaction Showed How Doomed Germany Was…

When The Germans Saw The American Jeep Roaming On D-Day – Their Reaction Showed How Doomed Germany Was… June 7th,…

End of content

No more pages to load