The P-51’s Secret: How Packard Engineers Americanized Britain’s Merlin Engine

August 2nd, 1941, Detroit, Michigan. Inside the Packard Motor Car Company’s East Grand Boulevard plant, the roar of engines echoed across the cavernous factory floor. Two engines sat on test stands, their polished aluminum and steel gleaming under harsh overhead lights, and then they came alive with a sudden, spine-tingling vibration. They weren’t ordinary engines. They weren’t American engines. They were Merlin engines, designed in Britain, rebuilt, and reimagined by American engineers to American standards. The moment marked a quiet revolution, invisible to the casual observer yet destined to change the course of the war in the skies above Europe. Every bolt, every bearing, every cylinder carried a story of ingenuity, precision, and the kind of problem-solving that defied the limits of conventional engineering. The crowd of engineers, technicians, and military observers knew they were witnessing something extraordinary, though few yet understood how deep the challenge had been, nor how high the stakes were.

The Merlin engine was not just an engine; it was a statement of craftsmanship, painstakingly built by skilled hands in Derby, England. Each Merlin contained nearly 14,000 precision parts, most of them assembled individually and fitted by artisans whose careers were devoted to making everything fit exactly. British tolerances were measured in fractions of thousandths of an inch, often adjusted by hand during assembly. A connecting rod that didn’t fit the crankshaft perfectly would be filed down, a bearing that seemed too tight would be adjusted, and supercharger impellers were balanced by eye, tweaked until spinning perfectly smooth. These engines were not designed for mass production—they were works of art. Rolls-Royce’s genius lay not in the raw numbers or horsepower but in the philosophy of meticulous, human-guided perfection. But this approach, while suitable for a few hundred engines a month, could not meet the urgent needs of a world at war.

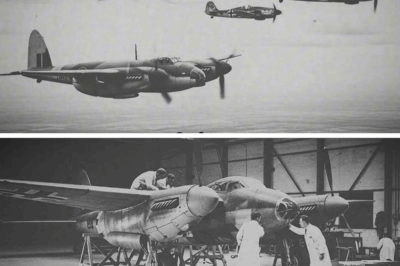

Across the Atlantic, the United States faced a crisis of its own. American aviation had produced the P-51 Mustang, a sleek, fast, and maneuverable fighter with a beauty that could not disguise a fatal flaw. Powered by the Allison V-1710 engine, the Mustang excelled at low altitudes, below 15,000 feet, performing admirably in speed, agility, and firepower. But as it climbed, the engine struggled. Above 20,000 feet, the single-stage supercharger could not compress enough air to maintain power. By 25,000 feet, where Luftwaffe fighters and anti-bomber operations thrived, the Mustang’s output dwindled to a fraction of its capacity. Above 30,000 feet, it was nearly powerless, unable to chase enemy aircraft or protect bombers flying deep into German territory. B-17 crews were vulnerable, exposed to coordinated attacks, their lives dependent on an engine incapable of reaching the altitude required for survival.

The solution, as it often is in war, required looking at what already existed and finding a way to make it American. Across the Atlantic, Rolls-Royce had already solved the high-altitude problem with the Merlin engine, featuring a two-stage, two-speed supercharger that could maintain sea-level pressures all the way to 30,000 feet. The engine was elegant, precise, and terrifyingly complex. But simply copying it was not an option. British Merlins were hand-built and incredibly difficult to replicate in mass quantities. Each engine required artisans, specialized tools, and patience—luxuries that American industry did not have the time to indulge in. The challenge for Packard was monumental: take an engine built for the slow, deliberate hands of craftsmen and reimagine it for an assembly line capable of producing thousands of engines without sacrificing performance, reliability, or the intricate balance that made the Merlin superior.

The first obstacle was measurement. British engineers worked in a system of imperial measurements that, while familiar on paper, was incompatible with American manufacturing standards. Rolls-Royce specified dimensions in thousandths of an inch, using techniques and conventions that had evolved over a century. Even the threads of bolts and screws followed the British Witworth standard, with its distinct 55-degree angle and rounded roots. American machinists were trained for a 60-degree thread with flat roots, standardized and uniform across factories. Every fastener, every nut, every connection had to be manufactured to British specifications while meeting American expectations for mass production interchangeability. This required designing entirely new tooling and retraining machinists to think in a system they had never used before. Every tap, die, and thread gauge had to be perfected, and every part inspected meticulously to ensure it would fit in any engine, anywhere, without adjustment.

Beyond measurements and threads, the philosophy of assembly posed an even greater challenge. British engineers assumed hand fitting. Components were allowed small variances because skilled workers would correct errors in real-time. Packard had to eliminate this margin for error. Every piston, bearing, and connecting rod had to fit precisely without human adjustment. The team, led by Connell Jesse G. Vincent, realized that to succeed, they could not merely copy the blueprints—they had to rethink them entirely for American production methods. Over eleven months, Packard engineers produced 6,000 new technical drawings, translating British hand-crafting techniques into mass-production processes while preserving every ounce of power, every curve of the supercharger, every cooling passage of the Merlin.

Even small details required careful consideration. The crankshaft bearings, for example, were originally made from a copper-lead alloy requiring careful break-in and frequent inspections. Packard substituted a silver-lead alloy with indium plating, creating a bearing that carried higher loads, ran cooler, and required less maintenance, all without altering the Merlin’s performance. British engineers were skeptical, but tests proved the American innovation improved the engine’s reliability and lifespan. Similarly, the supercharger impellers, which had to spin at more than 30,000 RPM, were re-imagined using precision casting and balancing techniques that minimized the need for hand-tuning, speeding production while maintaining perfect performance. The intercooler system, which managed extreme temperatures during air compression, was redesigned to improve flow and simplify manufacturing without sacrificing cooling efficiency.

By August 2nd, 1941, the first Packard-built Merlins were ready for testing. They roared to life on the test stands, the vibrations and sound filling the factory with a sense of achievement and anticipation. Engineers and military observers watched intently, knowing that these engines would power the P-51 Mustangs that might one day escort American bombers over Europe, keeping men alive and giving the United States a fighting chance in the skies. These were not just engines—they were the embodiment of American ingenuity, the perfect synthesis of British design and Detroit manufacturing prowess.

Detroit had performed what had seemed impossible: taking an engine designed for artisan hands and translating it into a mass-production marvel, with tolerances tighter than the original, parts interchangeable without adjustment, and performance equal or superior to the Rolls-Royce originals. The P-51 Mustang, once handicapped at high altitudes, would now fly with power and reliability that could match or exceed any Luftwaffe fighter. For the men flying them, the difference would mean life or death. For the war itself, it meant that American ingenuity had found a way to bend engineering to the nation’s will, creating a weapon that could finally fulfill its potential.

The test stands fell silent as the engines stabilized, the roar subsiding to a steady, confident hum. Every engineer in the room knew the stakes had been met, yet they also understood the work ahead was just beginning. Thousands of aircraft awaited these engines, thousands of pilots would depend on them, and the eyes of the world were watching as Detroit and Derby, England, bridged the gap between craftsmanship and mass production. The transformation was complete, but its full impact would not yet be felt. The Merlin engines sat ready, waiting for the skies to test their power, their precision, and the ingenuity of the engineers who had made the impossible possible.

Continue below

August 2nd, 1941, Detroit, Michigan. Inside Packard Motorcar Company’s East Grand Boulevard plant, two Rolls-Royce Merlin engines roared to life on test stands. But something was different. These weren’t British engines. They were Americanmade copies built from British blueprints that Packard’s engineers had completely rewritten.

The crowd watching that day had no idea they were witnessing an engineering revolution because hidden inside those engines was a secret that would transform World War II. The bearings were different. The tolerances were tighter. Even the thread patterns on every bolt had been painstakingly replicated from Britain’s arcane Witworth system.

Detroit had just turned a handfitted luxury engine into America’s most mass-roduced power plant. And they’d done it by breaking every rule Rolls-Royce held sacred. This is the untold story of how Packard engineers solved an impossible problem. Not by winning battles, but by conquering something far more difficult. converting 14,000 precision parts from imperial measurements to American mass production without losing a single horsepower.

In early 1942, the United States Army Air Forces had a fighter they loved and a fighter they couldn’t use. The P-51 Mustang powered by the Allison V1710 engine was beautiful at low altitude, fast, agile, deadly below 15,000 ft. But above that, it became a struggling, gasping liability. The problem wasn’t the airframe.

North American aviation had designed a masterpiece. The problem was physics. The Allison engine used a single stage supercharger that simply couldn’t compress enough air at high altitude. By 25,000 ft, where German fighters operated with ease, the P-51 was down to barely a,000 horsepower. By 30,000 ft, it was essentially helpless.

The cruel irony, American bomber crews desperately needed escort fighters that could operate at precisely those altitudes. B17 flying fortresses cruised between 25 and 30,000 ft on their bombing runs deep into Germany. Without fighters capable of matching that altitude performance, they were being slaughtered.

In August 1943, during the raid on Schwinford, 60 bombers were destroyed in a single mission. The Luftwaffa knew the Allison Mustang’s weakness. They simply climbed above it and waited. What the Army Air Forces needed wasn’t a new fighter. They needed a new heart for the one they already had. 3,000 m away in Derby, England, Rolls-Royce Limited had the solution.

Their Merlin engine was powering Spitfires and hurricanes to altitudes the Allison could only dream about. The secret was a two-stage, two-speed supercharger system designed by engineer Stanley Hooker that maintained seale pressure all the way up to 30,000 ft. But the Merlin wasn’t just an engine. It was a philosophy.

Every Rolls-Royce Merlin was essentially handbuilt. 14,000 individual parts, each one fitted by skilled craftsmen. When a connecting rod didn’t quite match the crankshaft, a worker filed it until it did. When bearing clearances varied, they were individually adjusted. The British standard Witworth thread system with its 55° angle and unique radius corners meant every fastener was custom manufactured.

Operating tolerances in the supercharger measured 0.001 0001 in. That’s the thickness of a human hair divided by four. Cylinder heads were individually matched to blocks. Supercharger impellers were balanced by hand. This wasn’t mass production. This was art. And Britain couldn’t make them fast enough.

By September 1940, with the Battle of Britain raging overhead, Rolls-Royce’s shadow factories in Crew, Manchester, and Glasgow were running 24 hours a day. They were producing roughly 200 engines per week. They needed 2,000. The British government looked across the Atlantic. Could American industry help? But what they didn’t know was that they were about to ask Detroit to perform an engineering miracle that seemed mathematically impossible.

convert precision craftsmanship into assembly line manufacturing without changing a single dimension, losing a single horsepower or compromising a century of Rolls-Royce engineering tradition. The real challenge wasn’t building engines. It was translating an entirely different industrial philosophy into the language of American mass production.

When Rolls-Royce engineers arrived in Detroit in September 1940, they brought crates containing complete Merlin engines. hundreds of blueprints and unwavering confidence in their methods. The licensing agreement was worth $130 million, astronomical money for 1940. Packard Motorcar Company wasn’t an obvious choice.

They built luxury automobiles, not aircraft engines. But they had something Rolls-Royce didn’t. American manufacturing genius. The moment Packard’s engineering team examined the blueprints, they knew they had a problem. Actually, they had about 14,000 problems. First problem, the measurement systems were incompatible. Britain used imperial measurements, but not the same imperial system America used.

Rolls-Royce specified dimensions in thousands of an inch, but their baseline standards came from the British engineering tradition that predated standardization. Converting these to American specifications wasn’t simple math. It required understanding the intent behind every tolerance. Second problem, the British standard Witworth thread system.

Every bolt, every nut, every threaded connection used a 55° angle thread form with radiused roots and crests. American unified fine threads used a 60° angle with flat roots. They weren’t interchangeable. Packard would need to manufacture every single fastener inhouse using British specifications. Third problem, and this was the big one.

Rolls-Royce’s tolerances were designed for hand fitting. When British workers assembled a Merlin, they expected to adjust parts as they went. Clearances of plus or minus several thousand of an inch were common because craftsmen would make it fit. Detroit didn’t work that way. American automotive production required perfect interchangeability.

Any engine component had to fit any engine. Period. No filing, no adjusting, no skilled craftsman making it work. The British engineers were polite but skeptical. Could American factories really maintain Rolls-Royce standards? Lead engineer at Packard, Connell Jesse G. Vincent, gave them a surprising answer.

Your tolerances are too loose for us. The room went silent. What happened next would become legendary in engineering circles. Packard didn’t just copy the Merlin. They reinvented how it could be manufactured while keeping its DNA intact. Over 11 months, Packard engineers created 6,000 new technical drawings. Not because the British blueprints were wrong, but because they were incompatible with mass production.

Every dimension was repppecified. Every tolerance was tightened. Every manufacturing process was re-imagined for the assembly line. But the real genius was in the details. Take the crankshaft bearings. Rolls-Royce used a copper lead alloy that required careful breakin and frequent inspection. Packard’s metallurgy team, drawing on American aircraft engine research, substituted a silver lead alloy with indium plating.

The silver provided better load carrying capacity. The indium created a microscopically smooth surface that reduced friction and improved break-in characteristics. British engineers initially objected. This wasn’t the Rolls-Royce specification. But when testing showed the Packard bearings actually lasted longer and ran cooler, Rolls-Royce quietly adopted the American innovation for their own engines.

The thread problem seemed insurmountable. Packard couldn’t just switch to American threads. That would make engines incompatible with British aircraft and spare parts. So, they did something extraordinary. They created entirely new tooling to manufacture British standard Witworth threads to American automotive precision standards.

Every tap, every dye, every thread cutting tool was custom manufactured. Packard purchased specialized thread measuring equipment from Britain. They trained American machinists in a thread system most had never seen before. BSW for coarse threads. BSF British Standard Fine for precision connections. BA British Association for small instrument fasteners.

The result, Packard built Merlin used exactly the same thread specifications as Rolls-Royce engines. You could swap parts between Detroitbuilt and Derby built engines without hesitation. But here’s what made it revolutionary. Packard manufactured those British threads to tighter tolerances than Rolls-Royce did.

Every fastener was precisely within specification. No hand fitting required. Perfect interchangeability. Then came the supercharger, the heart of the Merlin’s high alitude performance. The two-stage two-speed system used two impellers on the same shaft driven through gear trains. In low-speed mode, the ratio was 6.391 to1.

In high-speed mode, activated by a hydraulic clutch, it jumped to 8.095 to1. Those impellers had to be manufactured and balanced to tolerances measured in 10,000 of an inch. At operating speed, they spun at over 30,000 RPM. The slightest imbalance would destroy the engine. Rolls-Royce balanced them by hand, skilled workers adding or removing tiny amounts of material until the impeller spun perfectly smooth.

Packard developed precision casting and machining techniques that produced impellers so consistently accurate they required minimal balancing. They created dedicated test equipment that could measure dynamic balance while the impeller was actually spinning. The result was faster production and more consistent quality.

The intercooler system posed another challenge. Compressing air generates tremendous heat, as much as 205° C. To prevent detonation, the Merlin used an intricate cooling system with passages cast into the supercharger housing and an additional core between the supercharger outlet and the intake manifold. 36 gall per minute of ethylene glycol coolant circulated by a centrifugal pump carried away the excess heat.

Packard redesigned the coolant passages for more efficient flow and easier manufacturing without compromising cooling effectiveness. Every single system was analyzed, re-imagined, improved for production while maintaining performance. By August 1941, exactly 11 months after signing the agreement, Packard was ready.

The first V1651, Packard’s designation for the Merlin XX, ran on a test stand at the East Grand Boulevard plant. Winston Churchill reportedly wept when he heard the news. Britain would get the engines they desperately needed. But making one engine work was different from making 55,000 of them.

Packard transformed their factory into a precision engineering marvel. The production line for the V1650 used dedicated machining centers. Each one configured for specific operations. Crankshaft machining stations, block face milling stations, cylinder head stations. American automotive mass production philosophy demanded that every operation be repeatable and measurable.

If a crankshaft main bearing journal needed to be 2.2495 in in diameter, every crankshaft that came off the line measured 2.2495 in, not 2.2492, not 2.2498. Exactly right. every time. This eliminated the skilled hand fitting that Rolls-Royce relied on. A Packard line worker didn’t need years of apprenticeship. They needed good training and excellent machinery.

Production ramped up through 1942. By 1943, Packard was producing engines faster than North American aviation could build airframes to put them in. At peak production, the Detroit plant completed approximately 400 engines per week, double Rolls-Royce’s entire British output. The V1653, based on the advanced Merlin 63 with improved highaltitude performance, became the engine that transformed the P-51B Mustang into the war-winning Escort Fighter.

That two-stage supercharger could maintain over,200 horsepower at 40,000 ft altitude where the Allison wheezed and struggled. The most produced variant, the V1657, powered the iconic P-51D with its bubble canopy. At 1315 horsepower at sea level, it could pull the Mustang to 437 mph and sustain combat operations up to 40,000 ft.

Those engines escorted American bombers from England to Berlin and back. The Germans called it de americanisha Ral Fogle and learn to fear the sound of Merlin engines at altitude. By the time production ended in 1945, Packard had built 55,523 Merlin engines, more than all the Rolls-Royce factories in Britain combined.

The Packard Merlin represents something profound in engineering history. It proved that precision and mass production aren’t opposites. They’re complimentary when you understand the underlying principles. Rolls-Royce built exceptional engines through craftsmanship. Packard built exceptional engines through systems.

Both approaches worked, but only one could scale to the demands of total war. The techniques Packard developed, precision casting, statistical process control, dedicated tooling for consistent quality, became fundamental to modern aerospace manufacturing. When you fly in a Boeing or Airbus today, the jet engines are manufactured using descendants of the same principles Packard pioneered in 1941.

The bearing technology Packard developed for the Merlin influenced post-war automotive engineering. Those silver lead Indian bearings with their superior load carrying capacity and reduced friction became standard in high performance engines. Even the thread compatibility story has modern echoes.

Today’s international standards like isometric threads exist precisely because engineers learned from World War II that incompatible fastener systems create impossible logistics problems. But perhaps the most important legacy is philosophical. Packard proved that you could honor tradition while embracing innovation. They didn’t discard Rolls-Royce’s wisdom.

They translated it into a different industrial language. They kept the British thread specifications not because they had to, but because engineering integrity demanded it. That respect for interoperability, for standardization, for making systems work together shapes how we approach global manufacturing today. Several Packard Merlin still fly.

The Canadian War Plane Heritage Museum’s Lancaster bomber in Hamilton, Ontario, uses four original Packard engines. At Reno Air Races, unlimited class P-51s with modified Packard Merlin produce over 3800 horsepower, nearly three times the original specification. Those engines built more than 80 years ago still run, still perform, still demonstrate what American engineering achieved when necessity demanded the impossible.

The P-51 Mustang earned its reputation as perhaps the finest fighter aircraft of World War II. But its secret, the reason it could dominate the skies over Europe wasn’t just the airframe or the pilots. It was an engine designed in Derby, England, and perfected in Detroit, Michigan. The Packard Merlin story isn’t about one country’s engineering being superior to anothers.

It’s about complimentary strengths. British innovation created the Merlin’s revolutionary design. American manufacturing genius made it available in the quantities war demanded. 14,000 parts, 6,000 new drawings, 11 months of intense engineering work. The result changed the course of history. Next time you see a P-51 Mustang at an air show, listen carefully to that distinctive Merlin howl.

You’re hearing the sound of two engineering philosophies working in perfect harmony. British innovation and American mass production combined to create something neither could have achieved alone. If you found this story fascinating, subscribe to this channel for more deep dives into the engineering solutions that changed warfare.

Next week, we’re exploring another Invisible War winner. The story of how American engineers broke the Japanese purple code by building a mechanical computer from scratch without ever seeing the actual machine they were trying to replicate. Hit that notification bell. These are the stories they don’t teach in history class because they’re not about who won battles.

They’re about how problems got solved.

News

CH2 What Eisenhower Whispered When Patton Forced a Breakthrough No One Expected

What Eisenhower Whispered When Patton Forced a Breakthrough No One Expected December 22nd, 1944. One word kept echoing through…

CH2 Why Churchill Refused To Enter Eisenhower’s Allied HQ – The D-Day Command Insult

Why Churchill Refused To Enter Eisenhower’s Allied HQ – The D-Day Command Insult The rain that morning in late May…

CH2 When German Engineers Tore Apart a Mosquito and Found the Glue Stronger Than Steel

When German Engineers Tore Apart a Mosquito and Found the Glue Stronger Than Steel The smell of wood and resin…

CH2 How An “Untrained Cook” Took Down 4 Japanese Planes In One Afternoon

How An “Untrained Cook” Took Down 4 Japanese Planes In One Afternoon December 7th, 1941. 7:15 a.m. The mess deck…

CH2 How One Gunner’s ‘ILLEGAL’ Sight Turned the B-17 Into a Killer Machine

How One Gunner’s ‘ILLEGAL’ Sight Turned the B-17 Into a Killer Machine October 14th, 1943. The sky above Germany…

CH2 Japan Pilots Couldn’t Believe The Black Sheep Squadron Commanded the Skies

Japan Pilots Couldn’t Believe The Black Sheep Squadron Commanded the Skies The morning air over the Solomon Islands carried…

End of content

No more pages to load