The Texan Farm Boy Who Defied D.E.A.T.H Itself And The Real Life Captain America – How Audie Murphy Became The Greatest Soldier Of Modern Warfare

The boy who would one day be called the most decorated soldier in American history began life with little more than the Texas dust beneath his feet. The summer heat in Kingston, Hunt County, in 1925 pressed down like an anvil on the fields where young Audie Leon Murphy worked barefoot among the rows of cotton. He was small for his age, wiry and sharp-eyed, with a quiet stubbornness that could unsettle even grown men. The seventh of twelve children, he had learned early that silence and endurance were more useful than complaint.

The Murphy family’s wooden shack sagged on its foundations, the porch boards sun-bleached and splintered. His father, Emmett, was a restless man who drifted in and out of the family’s life like a shadow, chasing rumors of work that rarely existed. His mother, Josie Bell, held the family together through sheer willpower and faith. She was gentle, worn thin from childbirth and hard living, but she had a steel that Audie never forgot. When she smiled at him — weary but warm — he saw in her the quiet courage that would one day carry him through fire and fear.

By the time Audie turned twelve, the Great Depression had reduced the Texas countryside to near starvation. Cotton prices collapsed; families vanished in the night, their debts too heavy to bear. The Murphys picked what they could, sold what they could, and went hungry the rest of the time. Audie dropped out of school after the fifth grade to help support the family. He was just a boy, but in those endless, sun-cracked fields, he became a man without realizing it.

He hunted small game in the woods, teaching himself to shoot with a hand-me-down .22 rifle that was older than he was. The first rabbit he brought home, Josie cried when she saw it. It wasn’t much — a skinny animal, hardly worth the bullet — but it meant one meal they didn’t have before. Every shot after that carried more than the crack of gunpowder; it carried the weight of survival.

When Emmett finally disappeared for good, Josie’s health began to fail. The long years of exhaustion caught up to her, and one winter morning in 1941, she didn’t wake. Audie was sixteen. Her death left the younger children scattered among relatives, but Audie refused to leave Texas. He stayed behind, restless, drifting from one low-paying job to another, always with the same dull ache in his chest. He didn’t belong anywhere now.

Then, in December, the news came over the radio — Pearl Harbor. America was at war.

Something in him stirred at the words. The country that had offered him so little suddenly needed him. For the first time, he saw a way out — not from Texas, but from insignificance.

He tried to enlist the next morning.

The Navy turned him down. The Marines shook their heads. The Army recruiter looked him up and down, saw the narrow shoulders and boyish face, and laughed. “Come back when you grow a few inches, kid.”

But Audie Murphy didn’t give up.

For months he kept returning, sometimes standing outside the recruitment office like a stray dog waiting to be noticed. Finally, in June 1942, when he claimed to be eighteen — though he was barely seventeen — the U.S. Army accepted him. At five foot five and weighing 112 pounds, he looked more like a schoolboy than a soldier. The Army doctor wrote in the margins of his exam: “Undersized but fit for duty.”

Continue below

The boy who would one day be called the most decorated soldier in American history began life with little more than the Texas dust beneath his feet. The summer heat in Kingston, Hunt County, in 1925 pressed down like an anvil on the fields where young Audie Leon Murphy worked barefoot among the rows of cotton. He was small for his age, wiry and sharp-eyed, with a quiet stubbornness that could unsettle even grown men. The seventh of twelve children, he had learned early that silence and endurance were more useful than complaint.

The Murphy family’s wooden shack sagged on its foundations, the porch boards sun-bleached and splintered. His father, Emmett, was a restless man who drifted in and out of the family’s life like a shadow, chasing rumors of work that rarely existed. His mother, Josie Bell, held the family together through sheer willpower and faith. She was gentle, worn thin from childbirth and hard living, but she had a steel that Audie never forgot. When she smiled at him — weary but warm — he saw in her the quiet courage that would one day carry him through fire and fear.

By the time Audie turned twelve, the Great Depression had reduced the Texas countryside to near starvation. Cotton prices collapsed; families vanished in the night, their debts too heavy to bear. The Murphys picked what they could, sold what they could, and went hungry the rest of the time. Audie dropped out of school after the fifth grade to help support the family. He was just a boy, but in those endless, sun-cracked fields, he became a man without realizing it.

He hunted small game in the woods, teaching himself to shoot with a hand-me-down .22 rifle that was older than he was. The first rabbit he brought home, Josie cried when she saw it. It wasn’t much — a skinny animal, hardly worth the bullet — but it meant one meal they didn’t have before. Every shot after that carried more than the crack of gunpowder; it carried the weight of survival.

When Emmett finally disappeared for good, Josie’s health began to fail. The long years of exhaustion caught up to her, and one winter morning in 1941, she didn’t wake. Audie was sixteen. Her death left the younger children scattered among relatives, but Audie refused to leave Texas. He stayed behind, restless, drifting from one low-paying job to another, always with the same dull ache in his chest. He didn’t belong anywhere now.

Then, in December, the news came over the radio — Pearl Harbor. America was at war.

Something in him stirred at the words. The country that had offered him so little suddenly needed him. For the first time, he saw a way out — not from Texas, but from insignificance.

He tried to enlist the next morning.

The Navy turned him down. The Marines shook their heads. The Army recruiter looked him up and down, saw the narrow shoulders and boyish face, and laughed. “Come back when you grow a few inches, kid.”

But Audie Murphy didn’t give up.

For months he kept returning, sometimes standing outside the recruitment office like a stray dog waiting to be noticed. Finally, in June 1942, when he claimed to be eighteen — though he was barely seventeen — the U.S. Army accepted him. At five foot five and weighing 112 pounds, he looked more like a schoolboy than a soldier. The Army doctor wrote in the margins of his exam: “Undersized but fit for duty.”

Basic training at Camp Wolters, Texas, hit him like a hammer. The days began before sunrise and ended long after dark. Mud, sweat, and gun oil became the texture of his world. The bigger recruits mocked him — “Hey, runt!” — but the laughter died when they saw him shoot. Murphy could hit a tin can at 200 yards without missing once. He ran until his legs burned, pushed until his arms shook, and learned to carry his fear like another piece of equipment on his back. By the end of training, even the instructors knew better than to underestimate him.

When he boarded the troop ship to North Africa in early 1943, the sea stretched endless and blue, the air thick with diesel and salt. He stood on deck watching the horizon and felt something shift inside him — not excitement, not exactly fear, but the realization that the rest of his life would be decided out there, across that water.

In February, his unit — Company B, 15th Infantry Regiment, 3rd Infantry Division — landed in French Morocco. The men of the “Rock of the Marne” were hardened veterans of the campaign already, their humor rough and their eyes older than their years. They looked at Murphy and saw a kid. But war has a way of aging boys overnight.

By July, he was in Sicily. The land smelled of olives and gunpowder, the air humming with the whine of Messerschmitts overhead. His first firefight began at dawn near the beaches of Licata. German machine guns opened up from a ridge, tearing through the dry grass like scissors through paper. Murphy dove into the dirt, heart hammering, hands trembling on his rifle. The man beside him — a Texan from Amarillo — was hit before he could drop.

Murphy didn’t freeze. He sighted the ridge, exhaled, and squeezed the trigger. One German fell. Then another. His body moved before his mind could catch up, reloading, aiming, firing, until the machine gun went silent.

When it was over, he sat in the dirt, breathing hard, his face streaked with mud and blood. The sergeant clapped him on the shoulder. “You all right, kid?”

Murphy nodded slowly. “I guess I’m getting used to it.”

By September, he was fighting at Salerno. The mountains above the beach were riddled with German guns. The men of Company B were pinned behind a low stone wall, unable to move without drawing fire.

Murphy watched for ten minutes — maybe less — as bullets chewed through the rocks above their heads. Then, without a word, he rose to his knees, grabbed a grenade, and crawled forward through the grass. The others shouted after him, but he didn’t stop. The world had shrunk to the sound of his own breath and the sharp, metallic clink of the pin coming loose.

He lobbed the grenade into the nest. A flash. A scream. He fired twice, fast. Silence followed.

When he returned, his platoon was staring. One man muttered, “That kid’s crazy.”

“No,” another said, shaking his head. “He’s just not afraid.”

They were wrong. Murphy was afraid — he just never let fear decide his next move.

By the winter of 1944, he was a sergeant, his reputation growing with each battle. In January, at Anzio, the 3rd Infantry Division dug into the muddy plains under the constant howl of German artillery. The ground shook for weeks. Men disappeared overnight, buried in their foxholes by the blasts.

Murphy caught malaria twice but refused evacuation both times. He stayed with his men, gaunt and fevered, his uniform hanging loose on his small frame. When the Germans counterattacked in March, twenty tanks and waves of infantry rolled toward their line. From a shattered farmhouse overlooking the canal, Murphy spotted the advance and called in artillery strikes. He adjusted each round by eye, shouting coordinates into the field phone as shells exploded around him.

The lead tank burned. Crewmen bailed out and ran. Murphy shot them one by one before they could man their guns again. That night, when he realized the enemy might return to repair the tank, he led a patrol through the dark to destroy it completely.

They crawled through mud under moonlight, breath fogging in the cold. He motioned to the men to stay back, crept the last fifty yards alone, and fired rifle grenades until the Panther erupted in flame.

He came back grinning, soot smeared across his face. “Won’t be using that one again,” he said.

The men laughed — the first real laughter they’d had in days.

For his actions at Anzio, Murphy earned the Bronze Star with Valor. But he never mentioned it to anyone. The medal stayed buried in his duffel bag, forgotten. For him, the war wasn’t about decorations. It was about keeping the man next to him alive another day.

By June, the Allies had captured Rome. The world cheered. Murphy barely noticed. He cleaned his rifle, checked his gear, and waited for the next set of orders. He didn’t know that the next operation would push him further than he’d ever imagined — into the burning hills of southern France, where the boy from Texas would finally become a legend.

The Mediterranean in August 1944 shimmered like polished glass, deceptively calm above a sea that hid the iron weight of war. Hundreds of Allied ships drifted in silent formation off the coast of southern France — a vast armada waiting for dawn. From the decks came the low hum of engines, the scrape of boots, and the murmur of prayers.

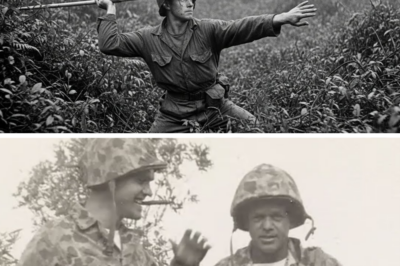

In the belly of one landing craft, Lieutenant Audie Murphy — barely twenty, though his eyes carried the exhaustion of fifty — checked his rifle one last time. The weapon’s metal was warm under his fingers, the same Springfield carbine he’d carried across Africa and Italy. Around him, the men of Company B sat in silence, faces streaked with salt and grime. The air smelled of diesel, cordite, and fear.

He looked from face to face — the replacements, the survivors, the ghosts that never really left. Some chewed gum. Others just stared at the dark outline of the French coast ahead.

Murphy glanced toward his closest friend, Private Lattie Tipton, a big, easygoing man from Tennessee whose laughter had a way of cutting through even the worst nights. Tipton grinned and nudged him.

“Bet France smells better than Sicily,” he said.

Murphy smirked. “Give it five minutes after the shooting starts.”

The ramp clattered down at 0800 hours near Cavalaire-sur-Mer. The men poured out into waist-deep water as the world exploded above them. Naval guns from offshore thundered overhead; smoke and sand filled the air. The first thing Murphy noticed was the vineyards — endless rows of grapevines climbing the hills beyond the beach, beautiful even under shellfire. The second was the sound of German MG-42s opening up from the tree line.

They hit the ground running. Bullets hissed past like hornets. Somewhere behind him, a man fell with a cry. Murphy didn’t turn. His boots found the rocky shore, his rifle came up, and instinct took over. He moved low and fast, firing short, controlled bursts.

By noon, they had pushed inland through a cluster of stone farmhouses. Smoke hung over the fields, the air heavy with the smell of burning oil and crushed grapes. The Germans had fallen back to the high ground — a ridge above the vineyards — and they were waiting.

Company B hit the slope and was pinned immediately. Machine-gun fire raked the hillside, cutting down anyone who tried to move. The men dove behind walls and ditches, shouting over the chaos.

Tipton crouched beside Murphy, his face pale under the grime. “They got us boxed in, Audie.”

“Not for long,” Murphy muttered. He peered through the sight, tracking the flicker of muzzle flashes on the ridge. He could feel the heat of the gunfire on his face.

They traded fire for what felt like hours. The Germans were dug in deep, their guns protected by sandbags and stone. Ammunition ran low. Men screamed for medics who never came. Then, somewhere in the distance, a white scrap of cloth fluttered above the ridge.

Tipton saw it first. “They’re surrendering!” he shouted, rising to his feet.

Murphy’s hand shot out. “Lattie, wait—”

The words died in his throat as the white flag dropped and the ridge erupted in fire.

Tipton jerked once, twice, then fell backward into the dirt. Murphy caught him before his head struck the ground. The big man’s eyes stared up at the sky, unseeing.

For a heartbeat, Murphy couldn’t move. The noise of battle dulled, the world shrinking to the weight of his friend in his arms. The smell of blood and dust filled his nose. Then something inside him — something small and hard and cold — snapped.

He rose.

The world slowed to a crawl. He sprinted back through the lines, grabbed a light machine gun from a wounded gunner, and charged straight toward the ridge alone. The men behind him shouted for him to stop. He didn’t hear them.

Bullets whipped past, kicking up dirt at his heels. He dropped to one knee, fired in long, brutal bursts, then rose again and kept moving. The air shimmered with heat and fury. He could see the faces of the Germans now — boys, really, no older than him — frozen in disbelief as the small American tore through their ranks.

Grenades exploded ahead, showering him with fragments. He didn’t slow down. He reloaded, switched to his carbine, and kept advancing. When he finally reached the crest, smoke stung his eyes. The German machine gun fell silent. Five men stumbled from a dugout, hands raised.

Murphy lowered his weapon. “Get up,” he said quietly. “And start walking.”

Behind him, the hillside was littered with bodies — the price of rage, the cost of grief.

That night, when the shooting stopped, the survivors of Company B sat in stunned silence. The air was heavy with exhaustion and disbelief. One man finally spoke. “Murphy did it. He took the whole damn ridge.”

They wrote it up later — the attack, the bravery, the single-handed assault — and called it gallantry. But for Murphy, it was just vengeance. He never forgave himself for what happened to Tipton.

When they pinned the Distinguished Service Cross to his chest weeks later, he kept his eyes on the ground. “I didn’t earn this,” he said softly. “He did.”

The days that followed bled together in an endless rhythm of marching, fighting, and waiting. The French countryside rolled past — burned-out villages, shattered bridges, fields littered with shell casings. Each battle took something from him: a piece of laughter, a sliver of trust, a fragment of the boy he had been in Texas.

By September, the 15th Infantry was driving north toward the Vosges Mountains. Rain fell almost daily now, turning the roads to rivers of mud. The Germans were retreating but fighting for every inch.

On the 15th of September, while Murphy’s company moved through a ravine near L’Omet, a mortar shell landed without warning. The blast threw him to the ground. When he woke, his head rang, his left ankle throbbed, and two men beside him were dead. He refused evacuation. “It’s just a scratch,” he told the medic, though blood seeped through his boot.

He limped through the next weeks, pushing forward with the division as they crossed the Moselle River into northeastern France. The landscape turned colder, darker. The air smelled of pine and gunpowder.

In late September, near the village of Le Clat, the Germans made a stand in an old stone quarry carved into the hillside. Machine guns bristled from every corner. The narrow valley became a deathtrap for anyone who entered.

When the order came to advance, Murphy was in front as always. He moved through the undergrowth, the weight of his carbine familiar in his hands. Bullets sliced through the trees. Men dropped around him. He kept going.

He crawled to within fifteen yards of a machine gun nest, the barrels flashing in the gloom. Two grenades — pull, throw, count. The explosion tore through the position. He waited for the smoke to clear, then sprinted forward and finished what was left with his rifle.

Later, his commanding officer, Colonel Keith Ware, found him cleaning the captured MG-42. “You realize you just took that nest by yourself?”

Murphy shrugged. “Didn’t see anyone else volunteering.”

Ware laughed quietly. “You’re going to run out of medals before you run out of courage.”

Murphy didn’t laugh. “Sir, I just want to get home.”

But home was a long way off.

Four days later, under a freezing rain, Murphy braved open ground to call artillery strikes on enemy positions. He lay in the mud for an hour, adjusting fire while bullets kicked up dirt around him. When it was over, fifteen Germans were dead, thirty wounded, and his company had taken the ridge.

That week alone, he earned two Silver Stars — an almost impossible feat.

He was promoted to second lieutenant soon after. The paperwork embarrassed him. He could barely read the forms, let alone fill them out. “You’ll learn,” Colonel Poch told him with a grin. “Besides, son, the army needs men like you leading from the front, not pushing pencils.”

Murphy obeyed — not because he wanted the rank, but because he couldn’t imagine standing anywhere else but the front line.

As the autumn turned to winter, snow began to fall over the Vosges. The forests were eerily quiet — the kind of silence that meant danger. Every footstep crunched like a warning.

Murphy’s body was worn to the bone, his uniform threadbare, but his eyes still burned with the same blue fire. He led patrol after patrol through the fog-drenched woods, each one more dangerous than the last.

On October 26, near the hamlet of Les Rouges Eaux, he was hit again — a sniper’s bullet smashing through his hip. He dropped instantly, pain tearing through his side. The radio operator behind him fell dead.

Murphy rolled into a ditch, blood seeping through his trousers. The sniper fired again, clipping the helmet that had rolled off his head. He spotted the glint of a scope in the trees and, gritting his teeth, raised his carbine. One shot. Then another. The rifle bucked in his hands. The sniper tumbled from the branches and hit the ground with a thud.

When the medics reached him, Murphy was pale and shaking, but alive. “Just a scratch,” he muttered through clenched teeth as they lifted him onto the stretcher.

It wasn’t. The wound turned septic. He spent two months in a field hospital near Épinal, fevered and delirious, drifting in and out of consciousness. The doctors nearly amputated. Penicillin — new and rare — saved his life.

When he finally stood again, a deep scar carved across his hip, the war should have been over for him. But Murphy refused to stay behind.

By early January 1945, limping but unbroken, he returned to his men — thinner, quieter, and harder than ever. He didn’t know it yet, but his greatest test was waiting on the frozen fields ahead.

A place called Holtzwihr.

And there, surrounded, wounded, and outnumbered five to one, the small man from Texas would face down an entire German force — and prove that legends are not born in glory, but in fire.

Snow fell in thick, silent sheets over the Alsace plain, softening the landscape but not the war. By the end of January 1945, the villages of northeastern France looked less like towns than broken bones scattered across the land. Holtzwihr was one of them — a small cluster of houses and a church steeple standing crooked under the white weight of winter.

Lieutenant Audie Murphy crouched at the edge of a frozen field, binoculars pressed to his eyes, breath misting in the air. Beyond the bare treeline, he could see movement — shadows against snow, shapes too deliberate to be tricks of light. German armor. At least six heavy tank destroyers, maybe Jagdpanthers. And behind them, the darker wave of infantry advancing through the gray morning.

He lowered the binoculars. The sound reached him next — a low, grinding rumble that trembled through the soles of his boots.

“They’re coming,” he said quietly.

The forty men of Company B, 15th Infantry Regiment, 3rd Division were in no shape to face a full armored assault. Weeks of fighting had reduced their numbers from over a hundred. Many were frostbitten, all were exhausted. Their two M10 Wolverine tank destroyers, parked along the road to Holtzwihr, were the only armor support left — and even those were aging machines, thinly armored and open-topped, hardly a match for German steel.

Murphy knew what was coming. He’d felt it before — that creeping pressure in the air before a storm. He glanced at his watch. Just past two in the afternoon.

The men shifted uneasily in the snow, breath clouding in the frigid air. Sergeant Elmer Brawley, a farmhand from Kentucky with frost in his beard, moved up beside him. “Lieutenant,” he said, voice low. “We can’t hold if those tanks roll through.”

“I know,” Murphy replied, scanning the treeline again. “We’ll fall back to the secondary line in the woods. Get the men ready. When I give the word, you move.”

“What about you?”

“I’ll call in artillery. Somebody’s gotta keep them busy.”

Brawley hesitated. “You’ll get yourself killed, Audie.”

Murphy gave a faint smile, the kind that never reached his eyes. “Not today.”

The first shells screamed overhead. The earth erupted in front of them as German artillery began to pound the position. Trees splintered, snow turned black with soil and smoke. The men ducked, covering their heads as shrapnel whined through the air.

“Move!” Murphy shouted. “Get back to the woods!”

They scrambled for cover as the tanks appeared — six dark beasts emerging from the haze, their long barrels glinting like fangs. Behind them, hundreds of infantrymen in white smocks advanced, rifles raised, moving with mechanical precision across the open field.

The Wolverines opened fire. Their 3-inch guns roared, shells streaking toward the lead tank. The first shot struck and ricocheted harmlessly. The second tank answered with a blast that tore through the American line, flipping snow and earth into the air.

“Goddammit,” someone shouted. “They’re too close!”

Murphy grabbed the field telephone, his voice sharp and steady. “Red Battery, this is Blue Two-One. Target enemy armor, grid seven-one by four-nine. Fire for effect.”

Seconds later, the horizon lit up with explosions as American artillery rained down on the advancing Germans. Smoke billowed, but the tanks kept coming.

Then, with a roar that seemed to tear the world open, the rear Wolverine took a direct hit. Flames shot skyward. The crew scrambled out, two of them already on fire. The air stank of fuel and burning rubber.

“Pull back!” Murphy yelled. “Get to the secondary line!”

The surviving Wolverine, trying to reverse into the trees, slipped sideways into a drainage ditch. Its gun jammed at an awkward upward angle, useless. The crew abandoned it and ran for cover.

For a moment, the field was chaos — smoke, snow, shouts, and the deep, steady thunder of German engines closing in. Murphy watched his men disappearing into the woods and knew someone had to cover their retreat.

He dropped the phone back into the mud and sprinted through the smoke toward the burning Wolverine. The heat hit him like a wall. Flames licked along the hull, ammunition inside popping and crackling like dry wood. He could feel the fire’s breath on his face as he climbed onto the metal beast.

“Murphy, get down!” Brawley shouted from the treeline.

He didn’t listen.

The .50 caliber machine gun mounted on the Wolverine was still intact. Murphy swung it around, the metal burning against his gloves. The Germans were only a hundred yards away now, moving through the smoke in scattered lines. He set his jaw, squeezed the trigger — and the world turned into thunder.

The heavy gun tore through the winter silence, spitting red tracers into the white field. German soldiers dropped by the dozen, their neat formation breaking apart in panic. The recoil pounded through Murphy’s arms, but he didn’t stop. He raked the snowline from left to right, cutting down anyone who moved.

Inside the headset, the artillery observer’s voice crackled: “Blue Two-One, adjust fire. How close are they?”

Murphy pressed the radio to his ear and said the words that would be remembered forever: “Just hold the phone. I’ll let you talk to one of the bastards.”

He ducked as bullets slammed into the hull below him, sparks leaping like fireflies. The air was thick with smoke and the stench of cordite. The Wolverine was burning from the inside now; each second felt borrowed. Yet he kept firing — long, controlled bursts, the rhythm almost hypnotic.

The German tanks hesitated. They could see the flames, assumed the Wolverine was manned and still deadly. They spread out, angling to flank it. But Murphy’s artillery called in again, the rounds whistling overhead and exploding among the advancing troops.

He switched targets, mowing down a fresh wave of infantry that tried to rush his position. Some crawled; some ran. None got close.

At one point, twelve soldiers rose from the ditch just ten yards away. Murphy swung the gun and fired until the belt clicked empty. When the smoke cleared, they were still.

Shrapnel from nearby explosions tore his coat and reopened the wound on his hip. Blood seeped into his trousers, freezing as it met the cold air. He ignored it.

For more than an hour, he held the line alone.

When his last belt of ammunition ran dry, he climbed down — limping, half-deaf, his face streaked with soot and blood. The Wolverine groaned behind him, flames roaring higher. He stumbled toward the treeline where his men waited, still firing short bursts with his carbine as he moved.

He had barely reached them when the tank destroyer exploded. The blast lifted him off his feet, showering the forest with metal and fire. He landed hard, rolled, and pushed himself up, dazed but alive.

“Lieutenant!” Brawley ran toward him. “You’re hit—”

“Shut up,” Murphy snapped. He leaned against a tree, panting, his hands shaking from exhaustion and adrenaline. “Get the men ready. We’re counterattacking.”

Brawley stared at him. “Counterattack? Sir, there’s a whole battalion out there!”

Murphy looked back toward the smoking field. The German advance had stalled. The surviving infantry were retreating toward the village, their tanks reversing under the renewed artillery fire.

“Exactly,” he said. “They’re running. Let’s finish it.”

With the remnants of Company B — barely thirty men — Murphy led the charge back across the frozen ground he’d just defended. The snow was red with blood and black with soot. The men moved like ghosts behind him, shouting as they went. The Germans broke completely, scattering into the woods beyond Holtzwihr.

When it was over, the field fell silent. Smoke drifted through the air. The smell of death hung heavy.

Murphy sank to his knees beside a shattered tree and pressed his hands to the bleeding gash on his leg. He could barely feel his fingers.

Brawley knelt beside him, shaking his head in disbelief. “You crazy son of a gun. You just held off a whole damn army.”

Murphy gave a faint smile. “I didn’t have much choice.”

They found him sitting there when the medics arrived, half-frozen and barely conscious. He refused evacuation until every wounded man from Company B had been carried out first.

Later, in his report, the artillery observer wrote simply: “One man delayed an entire German counterattack. Lieutenant Murphy’s actions saved his company from annihilation.”

But for Murphy, the day wasn’t about heroism. When they told him how many Germans had died — over fifty confirmed, with many more wounded — he looked away. “That’s not something to be proud of,” he said quietly.

He slept little that night. The image of the burning Wolverine haunted him, the faces of the men he’d killed flickering in the dark behind his eyes.

Days later, his commanding officer called him to headquarters. “Audie,” the colonel said, standing beside a desk stacked with reports. “You’ve been recommended for the Medal of Honor.”

Murphy stared at the paper, expression unreadable. “I just did my job, sir.”

The colonel smiled faintly. “You did a hell of a lot more than that.”

Outside, the snow began to fall again — silent, endless, indifferent.

Spring came slowly to the war-torn fields of France. By the time the snow melted and the guns finally fell silent, Audie Murphy had become a name whispered through every division of the U.S. Army. The boy who’d been turned away for being too small was now the most decorated soldier in American history — thirty-three awards for valor, each earned in places where few men had lived to tell about it.

He didn’t think about the medals much. He thought about faces — the ones that didn’t come back from Sicily, Anzio, the Vosges, Holtzwihr. When he tried to sleep, he saw them again. Lattie Tipton’s broad grin turning to shock. The nameless boy he shot at twenty paces. The German tanker burning alive inside his machine. They visited him like ghosts that didn’t know how to rest.

In June 1945, near Salzburg, Austria, he stood ramrod straight as Lieutenant General Alexander Patch pinned the Medal of Honor to his chest. Cameras clicked. A reporter asked him how it felt. Murphy looked down at the ribbon’s blue silk, then at his boots.

“Like it belongs to the guys who didn’t make it,” he said.

When he sailed home that August, the docks in New York were crowded with cheering civilians. Banners fluttered. Bands played. Women threw flowers from balconies. The war hero from Texas stepped down the gangway looking lost in the noise. His body was 20 years old; his eyes were ancient.

The Army wanted him to tour the country, sell war bonds, shake hands. He did it politely, smiling for photographs, signing autographs with a steady hand. But the applause felt hollow. The lights were too bright, the crowds too loud. In hotel rooms, when the doors closed, the quiet pressed in like the dark back in France. Sometimes, without realizing it, he’d dive to the floor at the slam of a door or the crack of fireworks outside.

Back in Texas, he was greeted as a hometown legend. Farmers lined the roads, waving flags as he drove by. The Murphy family — what was left of it — beamed with pride. Yet the farmhouse he once called home seemed smaller now, the rooms emptier. He wandered through them like a stranger walking through someone else’s life.

He had no money, no education, and no clear idea of what came next. He was too young for retirement, too restless for peace. Then came Hollywood.

James Cagney, the movie star known for his gangster swagger, saw something in the soft-spoken Texan. “You’ve got presence, kid,” he said, handing him a cigarette on the Universal Studios lot. “People believe you before you open your mouth. That’s rare.”

Cagney offered him a contract. It wasn’t glamour that tempted Murphy; it was distraction. Acting, he figured, couldn’t be harder than surviving artillery fire.

The early years were rough. He stammered through lines, froze under studio lights, and flinched at sudden noises. Yet on screen, something about his quiet intensity worked. The camera loved him — or maybe pitied him.

By 1949, Murphy had found his rhythm. Westerns suited him best: simple morality, wide open spaces, the echo of gunfire against canyon walls. He rode horses like he’d been born in the saddle and handled a revolver with the same precision he once showed with his M1 carbine. Off set, though, the darkness still followed.

He married actress Wanda Hendrix that same year — a whirlwind romance the tabloids adored. But marriage couldn’t silence the nightmares. At night, he’d wake screaming, drenched in sweat, convinced the house was under attack. Wanda would find him crouched in the corner, eyes wide, hand gripping the pistol he kept under his pillow.

“I can’t reach him when he’s like that,” she told a friend once. “It’s like he’s still over there.”

They divorced in 1951. The newspapers called it a “Hollywood mismatch.” Murphy just called it inevitable.

His second marriage, to Pamela Archer, was steadier. She was a former airline stewardess — calm, kind, unafraid of his silences. Together they had two sons, Terry and James. To them, he wasn’t a hero; he was just Dad, who taught them to fish and told bedtime stories about a farm boy who learned to shoot so he could feed his family.

But even domestic peace couldn’t drown out the echoes.

In 1955, Universal Pictures released To Hell and Back, the film adaptation of Murphy’s autobiography. The studio wanted authenticity, so they cast him as himself. On set, he wore the same uniform, carried the same rifle, relived the same battles — and watched as stuntmen fell in the same ways his friends once had.

It broke something in him.

Between takes, he’d walk off into the California hills, chain-smoking in silence. Crew members whispered that he cried more than once behind the props truck. When the film premiered, audiences cheered and wept. It became the highest-grossing picture in Universal’s history for nearly two decades. Murphy smiled for the cameras, shook hands, and went home alone.

He’d done what was asked of him — turned his pain into entertainment.

The years that followed were a blur of work. Western after Western, war film after war film. His face aged but never softened; his voice carried the same clipped steadiness reporters once called “military calm.”

Yet beneath the surface, the war was eating him alive. He gambled recklessly, losing fortunes in a single night. He suffered mood swings that terrified even his closest friends. Some nights he’d drive for hours through the desert, headlights off, chasing silence that never lasted.

Doctors called it “battle fatigue.” Later generations would call it what it truly was — post-traumatic stress disorder. In the 1950s, there was no name, no cure, only whiskey and sleepless nights.

Still, he tried to make something good out of the wreckage. When the Korean War veterans began coming home, Murphy spoke publicly about their struggles, urging the government to recognize the hidden wounds of combat. “You can’t see the scars on a man’s mind,” he told a reporter once, “but they’re there all the same.”

He donated money quietly to veterans’ hospitals. He visited the wounded without cameras present. He testified before Congress, asking for better mental health support for soldiers. Few in Hollywood noticed; fewer in Washington cared.

By the late 1960s, his career slowed. The Westerns faded from popularity. His body — damaged by malaria, bullet wounds, and exhaustion — began to fail him. The same Army that once called him indispensable now felt like a memory from another life.

In 1971, at forty-five, he was still restless, still chasing something he couldn’t name. On May 28th, he boarded a twin-engine Aero Commander plane in Atlanta with five other men. They were heading to Virginia for a business meeting — routine, forgettable.

Somewhere over the Appalachian Mountains, fog rolled in thick as smoke. The pilot radioed that visibility was dropping. Minutes later, contact was lost.

For two days, search teams combed the hills near Catawba, Virginia. The wreckage was found on a forested ridge — twisted metal and silence. There were no survivors.

News of his death broke on Memorial Day weekend. America paused, stunned. The headlines read “AUDIE MURPHY, WAR HERO, KILLED IN PLANE CRASH.” Across the country, veterans lowered their heads.

At Arlington National Cemetery, he was buried with full military honors. Thousands attended. His wife stood motionless beside the casket, their sons holding her hands. A single bugler played Taps. The notes drifted over the green hills, soft and final.

At Murphy’s request, his headstone bore no gold lettering reserved for Medal of Honor recipients. Just a simple inscription:

AUDIE L. MURPHY

TEXAS

MAJ INFANTRY

WORLD WAR II

JUNE 20, 1924 – MAY 28, 1971

No mention of glory. No list of medals. Just a soldier’s name, rank, and dates — as if to remind the world that beneath the legend was a man who had simply done his duty.

In the years since, his story has become a myth told in classrooms and barracks, a symbol of courage and sacrifice. But the truth is harder, quieter. Audie Murphy was not fearless. He was human — a boy who carried a rifle because he had to, who fought because others depended on him, and who kept fighting long after the shooting stopped.

Courage, he once said, wasn’t the absence of fear. It was standing up and doing what needed to be done in spite of it.

Somewhere in the echo of his words, in the crackle of old film reels and the soft rustle of wind over his grave, that courage still lives — not as a story of medals, but as the memory of a man who gave everything he had to a world that never stopped asking for more.

News

CH2 Poor Cowboy Soldier Saved Two Beautiful German POW Sisters But GENERALS Came With A…

Poor Cowboy Soldier Saved Two Beautiful German POW Sisters But GENERALS Came With A… The morning was cold and…

CH2 They Mocked His ‘Ancient’ Javelin — Until He Pierced 8 Targets from 80 Yards

They Mocked His ‘Ancient’ Javelin — Until He Pierced 8 Targets from 80 Yards At 1:47 p.m. on April 14th,…

CH2 Germans Couldn’t Stop This “Unkillable” Commander — How He Destroyed 18 Tanks and Became Top Ace

Germans Couldn’t Stop This “Unkillable” Commander — How He Destroyed 18 Tanks and Became Top Ace At 7:23 on…

CH2 Canada’s Unusual Use of the 25-Pounder in World War II

Canada’s Unusual Use of the 25-Pounder in World War II The Canadian infantry had stopped moving. Somewhere ahead, German…

CH2 How a 24-Year-Old Montana Rancher Turned Captain’s ‘Trench Trick’ Ki11ed 41 Germans in 47 Minutes with a Single Tank Destroyer and a 50 Cal, and The Follow Is Heartbreaking

How a 24-Year-Old Montana Rancher Turned Captain’s ‘Trench Trick’ Ki11ed 41 Germans in 47 Minutes with a Single Tank Destroyer…

CH2 How a Left-Handed Mechanic’s Backward Loading Technique SHOCKED Third Army and DESTROYED 4 German Panzers in 6 Minutes

How a Left-Handed Mechanic’s Backward Loading Technique SHOCKED Third Army and DESTROYED 4 German Panzers in 6 Minutes The…

End of content

No more pages to load