THE INVISIBLE GHOST OF NORMANDY: How One Black Sharpshooter’s Ancient Camouflage Turned Him Into the Wehrmacht’s Worst Nightmare – Germans Never Imagined One Camouflage Method Would Be Able To K.i.l.l 500 of Their Soldiers

June 4th, 1944. Two days before the D-Day landings. The French countryside near Caen slept under a blanket of fog so thick it blurred the line between field and sky. The hedgerows stood silent like dark walls between meadows, and somewhere beyond them, the Atlantic murmured with the slow thunder of gathering ships.

Inside a low, dimly lit operations hut at a forward base in southern England, twenty soldiers sat shoulder to shoulder. The smell of oil, damp uniforms, and cigarette smoke hung heavy in the air. On the wall, a map of northern France stretched from Cherbourg to Bayeux, peppered with pins and strings marking German strongpoints.

At the front of the room stood Lieutenant Colonel Marcus Whitmore, his uniform immaculate, his voice sharp and deliberate. “Gentlemen,” he began, “you’ve been selected for an operation that will begin forty-eight hours before the main invasion. You’ll be landing ahead of the first wave to neutralize German observers, radio operators, and sniper nests across the Norman countryside. The success of the landings will depend on what you accomplish in those hours.”

Among the men listening sat Private First Class James Monroe Davis, age twenty-three, of the all–African American 366th Infantry Regiment. He kept his eyes fixed on the map, his hands folded quietly on his knees. To anyone else, he looked like another soldier in the crowd—disciplined, quiet, anonymous. But Whitmore’s orders had been explicit: Davis’s background made him essential.

Born in rural Mississippi during the Great Depression, Davis had grown up with nothing but his father’s worn rifle and the woods that surrounded their shack. By the age of eight, he could track, stalk, and take down a deer with uncanny precision. He’d learned not from a manual or a sportsman’s club, but from Old Gray Fox, a Creek Indian who lived alone by the river. The old man had taught him the ancient art of ghost walking—to become part of the forest, to move only when the world moved with you.

Lieutenant Colonel Whitmore paced before the map. “We’re up against elements of the German 352nd Infantry Division. They’re veterans from the Eastern Front—snipers who cut their teeth in Stalingrad and Sevastopol. They’ll be expecting trained sharpshooters. What they won’t expect…” He paused, turning toward Davis. “…are hunters who think like predators and ghosts, not soldiers.”

A few heads turned toward the young private. Davis said nothing.

Major Harold Reynolds, Whitmore’s deputy, stepped forward holding a folder. “We’ve reviewed your records. Some of you were hunters, trackers, or forest rangers before the war. That’s why you’re here.” He stopped in front of Davis. “Private Davis. I understand you were known back home for your ability to take deer without being seen.”

“Yes, sir,” Davis said simply.

“How many deer have you taken in your life?”

Davis thought for a moment. “Three hundred, give or take. Started when I was eight.”

“And how?” Reynolds pressed. “Blinds? Traps? Decoys?”

“No, sir. None of that. I learned to become the woods. I watched how the wind moved grass and leaves. I learned to move when the wind did—and never when it didn’t.”

The room was silent.

Reynolds exchanged a look with Whitmore. “You’ll demonstrate this technique tomorrow, Private. If it’s as effective as you claim, we may adapt it for the mission.”

The next morning, a cold English mist clung to the training field. The officers assembled at a clearing that resembled the Norman farmland they would soon face—rolling pastures bordered by hedgerows and patches of young wheat.

Davis stood beside them with his Springfield rifle slung over his shoulder. “Give me three hours,” he said. “Then try to find me.”

Whitmore checked his watch. “Very well. You have until eleven hundred.”

Three hours later, they returned. The field was silent. Whitmore, Reynolds, and Captain Frederick Parsons, a skeptical career officer from Boston, took turns scanning the open ground with binoculars. Nothing.

Parsons lowered his scope, annoyed. “He’s not out there. Probably found a ditch to hide in.”

“Keep looking,” Whitmore ordered.

Another thirty minutes passed. Then, from barely thirty yards behind them, a calm voice said, “I believe this demonstrates the technique, gentlemen.”

They spun around. Davis stood in the open field. For a long second, none of them spoke.

His uniform was unrecognizable. His entire body was wrapped in a hand-made suit of grass, mud, and twigs. The materials swayed naturally with every faint gust of wind. It wasn’t camouflage in the conventional sense. He didn’t look hidden. He looked expected—like he had always been there.

“My God,” Parsons whispered. “How long have you been standing there?”

“Since before you arrived, sir,” Davis said. “I watched you set up your post.”

Whitmore stepped closer, studying him. “Could you fight in that?”

“Yes, sir. Move, shoot, and reposition when needed. It works best if the materials come from the environment itself.”

Reynolds nodded slowly. “You could teach this to others?”

“The basics, sir. But mastery takes time.”

That night, Davis began instructing nineteen men in his methods. They learned to use the land like a painter used color—to blend with tone, not pattern. Standard-issue camouflage used regular shapes, predictable outlines. Davis’s approach was chaos with intent. Each man built a unique suit from local foliage and mud. When they moved, it was in sync with the wind.

Two nights later, under a moonless sky, they loaded into USS S-29, an old submarine modified for covert insertions. Their mission was simple and suicidal: land near Saint-Laurent-sur-Mer, infiltrate the inland countryside, and eliminate enemy observers before the main invasion force arrived.

The sea was rough, the air electric with anticipation. Davis sat on the bench beside Sergeant William Cooper, a tall, broad-shouldered Montanan who had been a forest ranger before the war.

“Nervous?” Cooper asked quietly.

Davis shook his head. “Focused.”

“I’ll tell you this,” Cooper muttered, checking his rifle. “I don’t care what color the hand is that’s keeping German scopes off my back.”

Davis gave the faintest smile. “Appreciate that.”

At 0200 hours, their small craft detached from the submarine and drifted toward the dark coast. No light, no sound. Only the rhythmic slap of waves against metal. When the keel scraped sand, they moved—rifles high, boots silent. Davis was first ashore.

The night was cold, the air laced with salt and gun oil. He crouched low, scanning the dunes, every nerve alive. Behind him, Cooper and the others spread out, vanishing into the hedgerows.

Their orders were clear: eliminate observation posts, disrupt communications, and survive until the main landings.

Davis moved inland alone. He stopped beneath an apple tree, inhaled deeply, and began gathering materials. Grass, twine, leaves, mud—the same ritual as home. He built his camouflage by touch, shaping himself into the earth. By dawn, he had vanished into it.

From his position on a ridge above Omaha Beach, he could see German sentries moving among sandbagged posts and machine-gun nests. Further inland, a thin column of smoke marked an observation station hidden in a farmhouse. Through his scope, he saw two soldiers—one scanning with Zeiss binoculars, the other adjusting a Feldfunk radio.

He waited. The wind shifted. The grass swayed.

One breath.

Two.

Then the Springfield cracked.

The observer dropped instantly, a hole where his right eye had been. The second man turned, confused, before collapsing beside him.

Davis did not move.

Standard doctrine said to relocate after firing. Davis stayed still, letting the world settle again. For thirty minutes, nothing stirred. Then a German patrol appeared—four men creeping toward the farmhouse. They found the bodies, shouted in alarm, and ran for cover.

Four more shots.

Four bodies.

By midmorning, German radio chatter buzzed with panic. Reports of an unseen marksman near Saint-Laurent began flooding their frequencies. The descriptions varied—some said it was a British commando, others swore it was an American with experimental camouflage. None imagined he was a Black man from Mississippi wearing a suit of local weeds and creek mud.

Davis intercepted a few fragments of their communication, catching words he recognized: Geistschütze—ghost shooter. Unsichtbarer Tod. Invisible death.

He adjusted his position by nightfall, relocating to a hedgerow near a crossroads where intelligence predicted another sniper team might set up. As dusk fell, the fireflies came out, glinting in the mist. He waited among them, breathing with the rhythm of the night.

At 2200 hours, three Germans arrived. Their leader wore an Iron Cross and carried a Gewehr 43 rifle with a scope—an Eastern Front veteran. They positioned themselves in a crossfire formation, watching for movement.

Davis watched them instead.

When the moon disappeared behind a cloud, he moved. Four hours of slow crawling brought him within one hundred yards. The Germans murmured softly, unaware that the ground itself was closing in.

At 0200 hours, three shots whispered through the night.

No one saw where they came from.

By dawn, Davis had accounted for nineteen kills. But his work was only beginning. The largest invasion in history was about to begin, and the Germans were starting to believe they were fighting an army of ghosts.

Continue below

June 4th, 1944. Somewhere in the French countryside near Khn Normandy, the morning fog clung to the rolling fields like a protective blanket, obscuring the view across the farmlands that would soon become a theater of war. In just 2 days, the largest amphibious invasion in military history would commence.

But the Germans manning their fortifications believed their Atlantic wall would repel any Allied assault with devastating efficiency. They had no idea that a single American soldier with an extraordinary talent would soon shatter their confidence and change the course of countless engagements.

This is the remarkable tale of how one man’s innovative approach to an ancient hunting technique would confound German forces and demonstrate that sometimes the most effective weapons on the battlefield are not the ones that come from factories, but from human ingenuity.

Private First Class James Monroe Davis of the All African-American 366th Infantry Regiment sat quietly in a briefing room at a forward operating base in southern England. At 23 years old, Davis had already lived a life more challenging than most of his fellow soldiers could imagine. Growing up in rural Mississippi during the Great Depression, he had learned to hunt from necessity rather than sport. His family’s survival had often depended on his ability to bring home game when times were tough, which they frequently were for a black family in the American South.

Gentlemen, we’ve got something special planned for you. Lieutenant Colonel Marcus Whitmore announced to the assembled group of 20 soldiers. Whitmore, a career military man with piercing blue eyes and a reputation for unconventional tactics, scanned the room.

The invasion is happening, and our regiment has been assigned a unique role that plays to certain specialized skills. Davis straightened in his chair. He had been hand selected for this meeting without explanation, pulled from regular duties and told only that his background might be valuable to an upcoming operation. Intelligence indicates German snipers have established positions throughout the Norman countryside, Whitmore continued, pointing to a large map of Northern France pinned to the wall.

Once our main forces move inland, these snipers will pick off our men, disrupt supply lines, and report positions to artillery. We need counter snipers deployed ahead of the main landing forces. A murmur ran through the room. Davis remained silent, but his mind was already calculating what this might mean.

Major Harold Reynolds stepped forward, a thick folder in his hands. We’ve reviewed your service records and backgrounds extensively. Each of you was selected because before the war, you demonstrated exceptional marksmanship or hunting skills. Reynolds approached Davis, handing him a dossier. Private Davis, I understand you were something of a legend back home for your ability to hunt deer without them ever knowing you were there. Davis nodded cautiously.

Yes, sir. My family needed the meat. Tell me, private, how many deer would you estimate you’ve taken in your lifetime? Reynolds asked. Davis thought for a moment. Probably close to 300, sir. Started when I was 8 years old. Reynolds smiled. And what was your technique? Hunting blinds? tracking? No, sir. Nothing so formal.

My family couldn’t afford fancy equipment. I learned from an old Creek Indian who lived near our farm. He taught me about what he called becoming the forest, making myself part of what the deer expected to see rather than hiding from them. Reynolds glanced at Whitmore with a knowing look before addressing the room.

Gentlemen, you’re being formed into specialized counter sniper units. You’ll deploy 48 hours before the main invasion. inserting by boat under cover of darkness. Your mission will be to neutralize German observation posts and sniper positions before they can report on our troop movements or inflict casualties.

Sergeant William Cooper, a square jawed man from Montana who had been a forest ranger before the war, raised his hand. Sir, with all due respect, most of us haven’t received specialized sniper training. That’s precisely why you’re here, Sergeant, Whitmore replied. The Germans are expecting military-trained snipers who follow standard operating procedures. They’re prepared for that.

What they’re not prepared for are hunters who learned their craft chasing deer through Appalachian forests or tracking elk across Montana ridge lines. Your unorthodox methods may be our greatest advantage. Davis flipped through the dossier.

It contained detailed maps of the Normandy countryside, aerial photographs of German positions, and technical specifications for the Springfield rifle he would be issued. But what caught his eye was a paragraph about camouflage techniques that mentioned the ineffectiveness of standard issue camouflage against German optics. Sir, Davis spoke up, his voice steady but quiet. These camouflage patterns won’t work against good spotters, especially in the open farmland of Normandy.

The room fell silent. It was unusual for a private to challenge operational details so directly, particularly a black private in the segregated military of 1944. To everyone’s surprise, Major Reynolds nodded. Davis is right. Standard camouflage is designed for general concealment, not for fooling trained observers with high-powered optics.

at variable distances. He turned to Davis. I understand you have some thoughts on this matter, private. Davis hesitated only briefly. Yes, sir. Back home, I developed my own method for getting close to deer. The Creek called it ghost walking. It’s not just about covering yourself in foliage or hiding.

It’s about understanding how your target sees the world and becoming something they expect to see. Go on, Whitmore encouraged. Animals don’t look for human shapes. They look for movement and things that don’t belong. Germans are trained to spot military camouflage, regular patterns, and sudden movements. My technique involves creating a suit from natural materials gathered on site, moving only when the wind moves the surrounding vegetation, and understanding how light and shadow work at different times of day. Captain Frederick Parsons, the officer who would be leading the operation, looked

skeptical. And this worked on deer. Sir, I could get within 15 ft of a white-tailed deer in broad daylight. They’d look right at me and go back to grazing. The suit changes with the terrain. In forest, it’s different than in field. On cloudy days, different than sunny. It’s never the same twice. Whitmore and Reynolds exchanged glances.

Private Davis, Witmore said finally. You have 24 hours to demonstrate this technique. If it proves as effective as you claim, we’ll consider implementing it for this operation. The next morning, Davis led a small group, including Whitmore, Reynolds, and Captain Parsons, to a clearing 2 mi from the base.

The area had been selected for its similarity to Norman farmland, open fields bordered by sparse woods and hedge. I’ll need about 3 hours to prepare, Davis explained. Then, I’d like you gentlemen to try to locate me using field glasses. I’ll be somewhere within 500 yd of this position. Reynolds checked his watch. Very well, private. We’ll return at 1100 hours.

When the officers returned, Davis was nowhere to be seen. They set up a small observation post and began systematically scanning the surrounding area with binoculars and a spotting scope. After 45 minutes of fruitless searching, Captain Parsons was becoming visibly frustrated. This is absurd. We’ve covered every inch of that field multiple times.

Keep looking, Whitmore instructed, his own curiosity peaked. Another 15 minutes passed. Reynolds was about to call off the exercise when a voice spoke from me nearly 30 yards away. I believe this demonstrates the technique, gentlemen. The officers spun around to see Davis standing in the open field behind them. He was covered in an extraordinary suit made of grasses, twigs, and mud, with strands of material that moved with even the slightest breeze. The effect was uncanny.

Not a man hidden by camouflage, but a man who had somehow become part of the landscape itself. “Good God,” Parsons whispered. “How long have you been standing there?” “Since before you arrived, sir, I watched you set up your position.” Witmore’s expression shifted from surprise to calculating interest. And you could apply this technique in combat conditions. With a rifle? Yes, sir.

The Creek used it for warfare long before they used it for hunting. The principles are the same. The suit needs to incorporate materials from exactly where you’re operating, and you need to understand how your targets vision works. What about the rest of the men? Reynolds asked. Can you teach them this technique? Davis hesitated.

I can teach the basics, sir, but it takes years to master completely. Still, even the fundamentals would make them much harder to spot than with standard issue camouflage. 2 days later, 20 counter snipers, including Davis, were loaded onto a submarine transport vessel under cover of darkness. Each man carried a Springfield boltaction rifle with a telescopic sight, 7 days of rations, a radio for emergency contact, and a sidearm.

What made Davis’s equipment unique was an additional havac containing various tools for crafting his specialized camouflage, twine, wire, fabric backing, and several small containers of natural pigments. As the vessel cut through the choppy channel waters, Davis sat quietly among his fellow soldiers. Despite having spent the previous day teaching them the fundamentals of his technique, there was still a palpable distance between him and the white soldiers.

The military remained segregated, and Davis was keenly aware of being the only African-Amean in the special unit. Sergeant Cooper settled onto the bench beside him, checking his equipment. Cooper had shown the most interest in Davis’s camouflage technique and had proven surprisingly adept at applying the basic principles.

“Nervous?” Kooper asked. Davis shook his head. “Not about the Germans, just focused on what needs doing.” Cooper nodded, understanding the unspoken reality. For what it’s worth, I don’t care what color the hand is that’s keeping German crosshairs off my back. Appreciate that, Davis replied simply. Captain Parsons made his way through the crowded vessel. We’re approaching the drop point.

Final equipment check, gentlemen. The small craft emerged from the submarine through a specialized chamber, then made its way silently toward the darkened coastline. No lights were visible from shore. a combination of blackout regulations and the late hour. Remember, Parsons whispered as they neared the beach.

You’ll be operating independently within your assigned sectors. Primary targets are German observation posts and sniper positions. Secondary targets are officers and radio operators. Avoid engagement with regular infantry unless absolutely necessary. We need to preserve the element of surprise for the main invasion. The boat nudged against the sandy bottom.

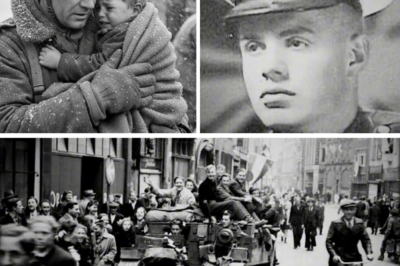

Davis was among the first group to wade ashore, moving silently through the shallow water with his rifle held high. The weight of history wasn’t lost on him. A black American soldier among the first to set foot in occupied France, coming to liberate a foreign land while his own people still struggled for basic rights back home.

Once ashore, the unit quickly dispersed into the darkness. Davis’s assigned sector was a three-mile stretch of farmland south of San Lauron Surmeare, an area that intelligence indicated contained at least two German sniper positions and an artillery observation post. Moving inland, Davis found a secluded cops of trees and began the process of creating his specialized camouflage.

Under the faint moonlight, he gathered grasses, branches, and soil, meticulously attaching them to the fabric backing he had prepared. By the time the eastern sky began to lighten, Davis had transformed himself into something that was neither man nor landscape, but a strange hybrid of both, a ghost capable of moving through the Norman countryside unseen. As dawn broke, Davis surveyed his surroundings.

The French countryside was beautiful despite the circumstances, rolling fields of wheat and barley, punctuated by ancient hedge and the occasional stone farmhouse. In the distance, he could make out a church steeple in a small village, likely occupied by German forces. His first objective was to locate the German positions in his sector without being detected.

Using a technique he’d refined hunting white-tailed deer in Mississippi, Davis began a painstakingly slow advance across the open field, moving only when the wind rustled the surrounding vegetation, freezing completely when it stilled. It took nearly 3 hours to cover 600 yd. Eventually, Davis reached a hedge row that offered both concealment and elevation.

From this vantage point, he could see a partially camouflaged German position approximately 400 yd ahead, a twoman observation post established in the upper floor of an abandoned farmhouse. Through his rifle scope, Davis could make out two soldiers. One was scanning the countryside with binoculars while the other manned a radio set.

They were from the 352nd Infantry Division. According to intelligence briefings, experienced troops transferred from the Eastern Front to bolster the Atlantic Wall defenses. Davis settled into position, becoming as much a part of the hedge as the ancient shrubs themselves. His breathing slowed to an almost imperceptible rhythm as he observed the Germans patterns.

The observer changed position every 20 minutes, moving between different windows to scan different sectors. The radio operator checked in with headquarters hourly on the hour. At 1100 hours precisely, Davis made his move. As the observer turned away from the window to speak to his companion, Davis squeezed the trigger. The crack of the Springfield echoed across the countryside.

By the time the sound reached the farmhouse, the observer had already fallen. Before the radio operator could react, a second shot found its mark. Davis didn’t move. Standard military training would have him relocate immediately after firing, but his hunting experience had taught him differently. Movement was what drew attention.

Instead, he remained perfectly still, becoming once again part of the landscape, watching and waiting. His patience was rewarded 30 minutes later when a German patrol arrived to investigate the silence from the observation post. Four soldiers approached the farmhouse cautiously, weapons ready. Davis observed them through his scope, noting their unit insignia and equipment.

These were regular infantry, not snipers or spotters, easier targets with less trained eyes. As they entered the farmhouse, Davis knew he had perhaps two minutes before they discovered their dead comrades and raised an alarm. He adjusted his position slightly, aligning his sights on the doorway. When the first soldier emerged running, Davis was ready.

Four measured shots later, the patrol lay motionless. By midafternoon, word had spread among German units of an Allied sniper in the area. Davis intercepted fragments of radio communications using the basic German phrases he’d been taught during training.

They were sending out specialized counter sniper teams, experienced marksmen from the Eastern Front who had played deadly games of cat and mouse with Soviet snipers amid the ruins of Stalenrad and Kursk. This was a different kind of hunting. Now the Germans would be looking specifically for him using techniques developed in the brutal urban combat of the Eastern Front. But Davis had an advantage they couldn’t anticipate.

They would be looking for a military-trained sniper using conventional tactics, not a Mississippi hunter employing techniques passed down from indigenous peoples who had hunted these lands centuries before Europeans arrived. As dusk approached, Davis carefully repositioned to a small drainage ditch that offered a view of a crossroads intelligence had identified as a likely location for a German sniper team.

He made subtle adjustments to his camouflage, incorporating more of the evening shadows into his design. His instincts proved correct. Just before sunset, a three-man German team, arrived at the crossroads. They moved with the practiced caution of experienced hunters, checking sightelines and potential hiding spots.

Their leader, a tall officer with a scoped rifle, systematically scanned the surrounding countryside. Through his scope, Davis could see the Iron Cross displayed prominently on the officer’s uniform, a decorated sniper brought in specifically to eliminate the threat.

The Germans established positions around the crossroads, creating overlapping fields of fire that would catch most conventional snipers attempting to target the area. Davis remained motionless as darkness fell. The Germans had set a trap, but it was designed to catch a conventional predator. Davis was something else entirely. Under the cover of darkness, Davis began an excruciatingly slow approach toward the German position, moving only inches at a time.

It took him 4 hours to close within 100 yards of the crossroads. The Germans had established a small observation post in a shallow depression, with two men keeping watch while the third slept. Davis could hear their whispered conversations, catching fragments of German mixed with the universal language of soldiers, complaints about food, officers, and the uncertainty of what the coming days would bring.

These men had no idea that the largest invasion force in history would be arriving on their shores in less than 48 hours. At approximately 0200 hours, Davis made his move. Three shots delivered with mechanical precision at close range eliminated the German counter sniper team before they could respond. For the first time, Davis felt something beyond the clinical detachment of a hunter. These men had been skilled predators like himself, worthy adversaries who simply had the misfortune of facing a technique they couldn’t have prepared for. Davis collected their identification tags and a map found on the officer’s

body which marked various German defensive positions in the sector. This intelligence would prove invaluable for the coming invasion. Over the next day, Davis continued his solitary hunt through the Norman countryside. His technique proved devastatingly effective against German observers who had been trained to look for conventional military threats.

By the eve of D-Day, he had neutralized 14 enemy positions, including three dedicated sniper teams sent specifically to eliminate him. As darkness fell on June 5th, Davis found himself on a rgeline overlooking Omaha Beach. In the distance, he could see the faint silhouettes of the invasion fleet gathering on the horizon.

Tomorrow, thousands of American soldiers would storm ashore into the teeth of German defenses. Many would not survive the day. Davis’s mission had been to improve their chances by eliminating observation posts that would direct artillery fire onto the landing zones. He was contemplating his next move when the radio on his belt crackled with a coded message.

All stalker units report status and position. Stalker 7 reporting. Davis responded quietly using his designated call sign. Position Charlie 4 niner. 14 confirmed neutralizations including three spider teams. request instructions. After a brief pause, Captain Parson’s voice replied, “Impressive work, 7, new mission parameters.

Proceed to Phase Line Baker and join with elements of First Infantry Division after landing. They’re being briefed on your special capabilities. Your mission will be to continue counter sniper operations during the inland advance.” “Uderstood,” Davis acknowledged. “Any word on the other stalker units?” Mixed results, Parsons replied carefully. Four units confirmed multiple neutralizations.

Three units failed to report. Two reported heavy resistance and withdrew to secondary positions. You’ve been our most effective operator by a significant margin. Davis absorbed this information silently. He had outperformed veteran hunters and militarytrained marksmen using a technique developed by necessity in the backwoods of Mississippi.

Seven,” Parsons added after a moment. “General Theodore Roosevelt Jr. specifically requested you for his follow-up operations based on your performance metrics. This could be significant for future considerations.” Davis understood the unspoken implication.

A black soldier distinguishing himself in combat, recognized by a general who happened to be the son of a former president, could have implications for both his personal future and potentially for broader military integration. Understood, sir, Davis responded. We’ll proceed to rendevous point at first light. As dawn broke on June 6th, 1944, the greatest amphibious invasion in military history began.

From his vantage point, Davis watched as landing craft approached the beach, immediately coming under heavy fire from German positions. The water turned crimson as men fell, yet others continued forward, determined to establish a foothold on Hitler’s fortress Europe. Davis knew his role was about to expand dramatically.

The specialized camouflage technique that had served him so well during the pre-invasion phase would now be tested in the fluid, chaotic environment of a major offensive. The Germans would be desperate, and desperate men became both more dangerous and more careless. As he watched the distant battle unfold, Davis thought back to his childhood in Mississippi to the old Creek man who had first taught him these techniques, explaining that becoming invisible wasn’t about hiding.

It was about understanding how to be seen without being noticed. The Germans had demonstrated time and again that they could not see what they did not expect to find. A black American soldier using indigenous hunting techniques to become a ghost on the battlefield. Sergeant William Cooper appeared beside Davis.

His own camouflage considerably improved after learning from Davis’s techniques, though still not as sophisticated. Quite a show, Cooper remarked, nodding toward the beach. Those boys are paying a heavy price, Davis observed soberly. Cooper glanced at Davis with newfound respect. Word is you’ve taken out 14 positions single-handedly. The rest of us combined didn’t manage that many.

Davis shrugged slightly. Just applied what I knew. Different kind of hunting, same principles. Well, whatever you’re doing, it’s working. Command wants it expanded. There’s talk of forming a specialized unit under your guidance, assuming you’re willing to teach others. Davis considered this. In civilian life, such an opportunity would have been unthinkable for a black man from Mississippi.

The irony that it took a world war for his skills to be recognized wasn’t lost on him. I’m willing, he said finally. But it takes a certain mindset. Not everyone can learn to think like prey in order to hunt the predator. Cooper nodded thoughtfully. I’ve been hunting elk in Montana since I was 12. Thought I knew everything about stalking.

After watching you work, I realized I didn’t know a damned thing. He paused. You’ve saved a lot of lives, Davis. Men who will never know your name will go home to their families because of what you’ve done here. Before Davis could respond, the radio crackled with new orders. The beach head had been established, and the First Infantry Division was moving inland.

Davis and Cooper were to proceed to a rendevous point 2 mi from their current position to join a specialized reconnaissance unit. As they prepared to move out, Davis made final adjustments to his unique camouflage. The strange suit of vegetation, mud, and fabric that had confounded German observers would need constant modification as they moved through different terrain.

It was labor inensive and required constant attention, but its effectiveness had been proven beyond any doubt. What neither man knew as they descended from the rgeline was that Davis’s technique would soon become legendary among both Allied and German forces. A ghost story whispered among German units about an invisible sniper who could strike from anywhere without being seen.

Some would attribute it to Allied technology or even supernatural intervention, never imagining that the most effective camouflage technique of the Normandy campaign had its origins in the hunting traditions of indigenous Americans. passed down to a young black man from Mississippi who had learned to hunt out of necessity rather than sport.

As they made their way toward the rendevous point, the sounds of battle echoed across the Norman countryside. The liberation of Europe had begun, and James Monroe Davis would play a role that military historians would study for generations, not just for its tactical significance, but for how it demonstrated that innovation often comes from unexpected sources, and that sometimes the most effective weapons are not technological marvels, but ancient knowledge applied in new ways. By midafternoon on D-Day, chaos reigned

across the Normandy countryside. The initial landings had secured a tenuous foothold, but German resistance remained fierce as Allied forces pushed in land. Private First Class James Monroe Davis and Sergeant William Cooper arrived at the designated rendevous point, a partially destroyed farmhouse serving as a temporary command post for elements of the First Infantry Division.

Captain Lawrence Sullivan, a battleh hardardened officer with a fresh bandage across his left cheek, greeted them with barely concealed surprise when Davis identified himself. “You’re the one they call the ghost?” Sullivan asked, studying Davis’s remarkable camouflage suit. “Intelligence said you’ve eliminated 14 observation posts single-handedly.” “Yes, sir,” Davis replied simply. Sullivan nodded, a hint of respect crossing his features.

General Roosevelt specifically requested your assistance. We’re having trouble with German snipers harassing our advance from the ridge line east of San Lauron. Our conventional counter sniper teams can’t get a fix on their positions. How many enemy snipers are we dealing with? Davis asked. Intelligence suggests at least a dozen, possibly more.

They’ve already taken out three of our officers and several radio men. They’re targeting anyone who looks like they might be in command. Davis considered this information. I’ll need a spotter, someone with patience and good eyes. Cooper here will continue with you, Sullivan replied. He’s already familiar with your unusual methods. Cooper nodded in agreement.

We’ve worked well together so far. Sullivan spread a map across a bullet riddled table. Here’s the situation. We need to advance along this road to link up with units landing at Utah Beach. The German snipers have established positions somewhere along these ridge lines. They have interlocking fields of fire covering our entire approach.

Davis studied the map. The terrain was challenging. Open fields offering little cover, bordered by hedge that could conceal dozens of snipers. I’ll need 6 hours, sir. Sullivan looked up sharply. 6 hours? We’re on a tight timet, private. 6 hours to locate and neutralize the sniper positions, Davis clarified. If you send men up that road before then, you’ll lose a lot of them.

Sullivan considered this, then nodded reluctantly. You have until 1900 hours. After that, we move regardless. Davis and Cooper departed immediately, making their way toward the contested ridge line through a series of drainage ditches and sunken farm tracks. Davis moved with a fluidity that continued to impress Kooper, not so much hiding as becoming part of the landscape itself.

“How do you move like that?” Cooper asked during a brief rest in the cover of a hedge. Davis adjusted elements of his camouflage suit, incorporating local vegetation. The Creek taught that animals don’t see like humans. They see movement first, shapes second, and details last. Germans with scopes are looking for shape and shadow, sudden movements, reflections.

The trick isn’t to hide. It’s to be seen without being recognized. You make it sound simple, Cooper remarked. The principle is simple. The execution takes practice. Davis surveyed the ridge line ahead through his binoculars. Most people try to hide completely.

That creates an absence, a void that trained observers notice. Better to be visible, but misunderstood. Cooper pondered this. Like seeing a bush, but not realizing it’s actually a man. Exactly. The human brain fills in what it expects to see. Germans expect American snipers to behave in certain ways, moving quickly between positions, using standard concealment techniques.

They don’t expect someone who can stand motionless for hours, becoming part of the landscape itself. As they approached the ridge line, Davis’s demeanor changed subtly. He became even more deliberate in his movements, studying every detail of the terrain ahead. 300 yards from the base of the ridge, he stopped abruptly, signaling Cooper to freeze. “There,” Davis whispered, nodding almost imperceptibly toward what appeared to be an ordinary section of Hedro.

“German sniper, top tier, Eastern front experienced.” Cooper strained to see what Davis had spotted. “How can you tell the birds?” Davis explained. Starings landed everywhere along that hedge row except that 10-ft section. Something disturbed them there, but nowhere else. Now Cooper could see it.

A subtle disruption in the natural pattern, almost invisible unless you knew precisely what to look for. “So what’s the play?” “We wait,” Davis replied, settling into an absolutely motionless position. “The best hunter isn’t the one who chases, but the one who anticipates.

” For the next 2 hours, they remained perfectly still, observing the German position. Occasionally they caught glimpses of movement as the sniper made minor adjustments to maintain his field of fire. Davis studied these movements intently, building a mental picture of his adversaries patterns and habits. “He’s good,” Davis commented quietly. “Chang his position every 18 to 20 minutes, minimal movement. Probably has a spotter we can’t see yet.

” As the afternoon wore on, Davis identified four more sniper positions along the ridge line. Each was masterfully concealed using conventional military techniques, positions that would have been nearly impossible to spot without his specialized knowledge of how to see what others missed. They’ve established a classic crossfire setup, Davis observed.

Any unit moving along that road will be caught from multiple angles. No wonder your counter sniper teams couldn’t get a fix on them. At approximately 1,700 hours, Davis made his move. Rather than targeting the snipers directly, he began a painstaking approach toward a position he had identified as likely to contain a German forward observer. The eyes that directed the snipers to their targets.

The approach took nearly an hour with Davis moving so gradually that his progress was imperceptible even to Cooper, who was specifically watching for it. Eventually, Davis reached a position less than 70 yard from where the German observer was concealed in a small depression overlooking the road. The shot, when it came, was so unexpected that Kooper himself was startled.

The German observer crumpled without a sound. Almost immediately, Davis shifted his aim and fired twice more in rapid succession, eliminating two previously unidentified radio men positioned nearby. The response was immediate and revealing. Two of the German snipers broke cover slightly, adjusting their positions to locate the new threat.

This momentary exposure was all Davis needed. Two more precisely placed shots, and the German sniper team was reduced by half. The remaining snipers were now in a difficult position. Their coordinated network had been disrupted, and they were facing an adversary who seemed to materialize and strike from nowhere. One attempted to withdraw to a secondary position, a fatal error that exposed him to Davis’s waiting crosshairs.

By 1830 hours, Davis had neutralized all five identified German sniper positions, plus three additional support personnel. The road to Utah Beach was now clear of the immediate sniper threat, allowing the first infantry division to proceed with their planned advance. When they returned to the command post, Captain Sullivan was visibly impressed.

Eight confirmed eliminations in less than 6 hours. That’s remarkable work, private. The technique is effective against conventional concealment methods, Davis explained modestly. German snipers are trained to hide from people looking for them. I’m not looking for them. I’m looking for the subtle ways they change the environment around them. Sullivan studied Davis thoughtfully.

General Roosevelt wants to see you. He’s establishing a specialized reconnaissance unit and believes your methods could be valuable across multiple sectors. The meeting with Brigadier General Theodore Roosevelt Jr. took place the following morning in a commandeered French farmhouse serving as a temporary division headquarters.

Despite being the son of a former president, Roosevelt was known for his unpretentious manner and willingness to lead from the front lines. He had landed with the first wave at Utah Beach despite being the oldest man in the invasion at 56 and walking with a cane due to arthritis and heart problems.

“Private Davis,” Roosevelt greeted him warmly. “Your reputation precedes you. 22 confirmed neutralizations in less than 72 hours using nothing but a standardisssue Springfield and what appears to be a suit made of grass and mud.” Davis stood at attention. “Yes, sir.” At ease, private. I’m interested in your technique. Captain Parsons tells me it’s derived from indigenous American hunting methods. Yes, sir.

I learned from a Creek Indian who lived near our farm in Mississippi. He called it ghost walking, a way of hunting that involves becoming part of what the prey expects to see rather than hiding from them. Roosevelt nodded thoughtfully.

And you believe you could teach this technique to others? The basics, sir? The fundamentals can be taught in days, though mastery takes years of practice. Here’s what I’m proposing, Davis. I want to establish a specialized unit under your guidance, a team dedicated to counter sniper operations using your methods. You would serve as lead instructor and field coordinator. Davis hesitated.

Sir, with respect, I’m not sure some of the men would accept instruction from from a negro soldier, Roosevelt finished bluntly. Perhaps not under normal circumstances, but these are not normal circumstances, and you’ve proven your value beyond any reasonable doubt. 22 confirmed eliminations speak louder than any prejudice. The newly formed unit, unofficially dubbed Davis’s ghosts, began operations 3 days later with eight carefully selected members drawn from various infantry regiments.

The selection criteria wasn’t previous sniper experience, but rather hunting background, patience, and most importantly, willingness to learn from Davis, regardless of racial differences. Their first mission together targeted a sector near Cararand, where German snipers had been particularly effective at impeding the American advance.

Davis spent a full day training his team in the basics of his technique, emphasizing the importance of understanding how their targets perceived the world. “Germans have been fighting on the Eastern front, where Soviet snipers operate differently than we do,” Davis explained to his assembled team. “They’re looking for quick movements between cover, standard military camouflage patterns, and the telltale signs of conventional sniper tactics. What we’re doing is fundamentally different.

” He demonstrated the construction of his specialized camouflage suit, showing how to incorporate local vegetation and soil to create something that became part of the landscape rather than merely blending with it. The key is movement, or rather the lack of it, Davis continued. A human can detect motion from incredible distances.

Deer can spot a hunter shifting position from 200 yd away. Germans with scopes can do even better. So, we move only when natural movement occurs around us, when the wind blows the grass, when shadows shift with the sun. The team’s first operation was a remarkable success.

Over the course of 48 hours, they eliminated 11 German snipers and observation teams with zero casualties of their own. Word of their effectiveness spread quickly through the American lines with units specifically requesting their support before difficult advances. General Omar Bradley, commanding the First Army, received reports of this unusual unit success and requested a demonstration.

In an audacious display of confidence, Davis volunteered to infiltrate the general’s own headquarters security perimeter using his technique, a challenge Bradley accepted with interest. The following morning, Bradley and his staff gathered for their regular briefing in a fortified command post.

Halfway through the meeting, Davis suddenly spoke from a corner of the room where he had been standing, completely unnoticed for over 30 minutes. General, I believe this demonstrates the effectiveness of the technique. Bradley, not easily surprised after decades of military service, was momentarily speechless.

Davis had penetrated multiple layers of security and positioned himself within feet of the highest ranking officers in the American Expeditionary Force without anyone detecting his presence. Extraordinary, Bradley finally remarked, and you can teach this to others. Yes, sir. Not to this level of proficiency quickly, but the basic technique can be taught in days. Bradley turned to his staff.

I want this method documented and implemented across all reconnaissance units. This could significantly reduce our casualties from enemy snipers. By mid July, Davis’s specialized unit had expanded to 24 members operating across the Normandy front. They had collectively accounted for over 100 confirmed neutralizations of German snipers, observers, and forward controllers.

German communications intercepted by Allied intelligence revealed growing concern about the phantom snipers who seemed able to strike without warning and disappear without trace. Obstilhelm Richa, a decorated German sniper instructor transferred from the Eastern Front specifically to counter this new threat, wrote in his field journal, “The Americans have deployed a new type of sniper using techniques we have not encountered before. Conventional counter sniper tactics prove ineffective.

They do not move between firing positions as expected, but seem to materialize from the landscape itself. Several of our best men have been lost without ever identifying their attacker. The German high command responded by deploying specialized hunter killer teams drawn from mountain divisions and forest rangers, men with extensive pre-war hunting experience similar to Davis’s background.

This escalation led to increasingly sophisticated duels between opposing sniper teams across the Norman hedge. On August 1st, Davis found himself hunting the hunter, tracking Oburst Richter himself through the densely vegetated terrain near files. Intelligence had identified Richtor as the mastermind behind the German counter sniper efforts, and eliminating him would significantly degrade their effectiveness.

The pursuit lasted 3 days with both men employing every trick in their considerable arsenals. RTOR, her former Bavarian gamekeeper with extensive experience hunting shamoir in alpine terrain, proved a worthy adversary. Twice he nearly turned the tables on Davis, setting cunning traps that would have caught a less experienced hunter.

The final confrontation occurred in a small valley south of Filets. Davis had been tracking subtle signs of RTOR’s passage, broken stems of grass bent in consistent patterns, slight disturbances in morning dew, the unnatural silence of birds in specific areas. These signs led him to a vantage point, overlooking a natural choke point between two hedros.

Davis prepared his position meticulously, incorporating elements of the surrounding vegetation into his camouflage suit, and settling into a shallow depression that offered both concealment and a clear field of fire. Then he did something counterintuitive, he deliberately created a subtle disturbance in the natural pattern of the area, the kind of disturbance that only a master hunter like Rtor would notice.

The bait was set, and Davis became as motionless as the earth itself, his breathing so shallow it wouldn’t disturb a butterfly perched on his chest. Hours passed. The sun climbed toward Zenith, then began its descent toward the western horizon. Near dusk, Davis detected the almost imperceptible signs of RTOR’s approach, not through sight, but through the behavior of a pair of finches that briefly altered their feeding pattern. The German was good, moving with a level of skill that Davis had rarely encountered.

But he was still thinking like a conventional hunter, stalking conventional prey. Richtor’s focus was on the subtle disturbance Davis had created, his experienced mind recognizing it as a potential sniper position. As he maneuvered to approach from an unexpected angle, he committed the one error Davis had been waiting for.

He momentarily silhouetted himself against the evening sky while crossing between two hedge. The single shot echoed across the valley. Obus Wilhelm Richter, decorated veteran of Stalingrad and the Caucasus, holder of the Knights Cross with oak leaves, fell without ever seeing his adversary.

In his journal, later recovered by American forces, his final entry read, “I hunt a ghost who has learned to hunt as the shadow hunts, not by chasing, but by being present when the prey arrives.” By late August, as Allied forces prepared for the liberation of Paris, Davis’s unit had expanded its operations to include training other reconnaissance teams in his specialized techniques.

Their confirmed elimination count had risen to over 300 German snipers, observers, and high-value targets. An extraordinary accomplishment that drew attention from the highest levels of Allied command. General Dwight D. Eisenhower, Supreme Commander of Allied forces in Europe, requested a personal briefing on the unit’s methods. The meeting took place at his forward headquarters in a French chateau near the front lines.

Davis, now promoted to staff sergeant based on his exceptional service, presented a detailed analysis of his technique and its effectiveness against German countermeasures. The fundamental principle, Davis explained to the assembled officers, is psychological rather than technological.

Germans expect American snipers to behave according to established military doctrine. When we operate outside those parameters using techniques derived from indigenous hunting traditions, they struggle to adapt. Eisenhower, known for his pragmatic approach to warfare, was immediately supportive. This is precisely the kind of innovative thinking we need. The Germans pride themselves on technical superiority and rigid tactical doctrine.

Your approach undermines both advantages. As the Allied advance continued through France and into Belgium, Davis’s unit faced new challenges. The terrain changed from the hedro country of Normandy to more open farmland and eventually to the dense forests of the Aransens.

Each environment required adaptations to the basic technique with Davis continually refining his methods to maintain their effectiveness. By December 1944, when the Germans launched their desperate Arden’s offensive, later known as the Battle of the Bulge, Davis’s specialized camouflage techniques had been adopted by sniper and reconnaissance units throughout the American forces.

The original unit, still led by Davis and now officially designated as the Special Reconnaissance Detachment, continued to perform critical operations targeting high-v value German assets. During the chaotic early days of the German offensive when American units were surrounded and communication lines severed, Davis led a daring operation to infiltrate German lines and gather intelligence on camp group Gripper Piper, the most effective German mechanized battle group.

Over the course of 4 days in temperatures well below freezing, Davis and three team members moved through German controlled territory, gathering critical information on unit dispositions, strength, and movement patterns. The extreme winter conditions required significant modifications to their camouflage techniques.

Davis developed a new variant incorporating snow, ice, and bare branches that proved equally effective in the winter landscape. German centuries, even those specifically watching for infiltrators, repeatedly failed to detect Davis and his team as they moved within yards of major German assembly areas. The intelligence they gathered proved crucial for American counterattacks in the northern shoulder of the bulge.

Major General Matthew Rididgeway, commanding the Istini Airborne Corps, specifically credited their information with saving hundreds of American lives by identifying previously unknown German artillery positions and supply routes. As winter gave way to Spring and Allied forces pushed into Germany itself, Davis faced perhaps his most difficult assignment yet.

Intelligence had identified a specialized German sniper school operating in the Hards Mountains, training a new generation of snipers in techniques specifically designed to counter Davis’s methods. The school was commanded by General Reinhardt Wolf, Germany’s most decorated sniper from World War I and a leading authority on counterinsurgency operations.

The mission to neutralize this threat was designated Operation Phantom and placed under Davis’s direct command. He selected seven of his most experienced operators, including Sergeant William Cooper, who had been with him since the pre-Day operations in Normandy. “This won’t be like anything we’ve faced before,” Davis warned his team during the mission briefing. “Wolf has been studying our techniques for months.

He’s training his students specifically to counter our methods. They’ll be looking for exactly the signs we try to eliminate. The operation began on April 12th, 1945 with the team infiltrating German lines near Thal at the northern edge of the Harts Range. The mountainous terrain was challenging with dense forests covering steep slopes and numerous caves offering perfect concealment for German observers.

Davis modified their approach accordingly, developing a new variant of his technique that incorporated vertical movement patterns designed for the three-dimensional environment of the mountain forests. The team advanced slowly, spending 3 days carefully approaching the suspected location of the sniper school.

On the fourth day, they encountered the first evidence of Wolf’s countermeasures, a sophisticated observation network using both human observers and trained dogs to detect infiltrators. This presented a new challenge, as Davis’s technique had been developed primarily to fool human vision rather than canine senses.

Drawing on his extensive hunting experience, Davis improvised a solution. The team collected specific herbs and fungi from the forest floor that masked human scent, incorporating these into their camouflage and rubbing them on their equipment and clothing.

Additionally, they began moving exclusively during rainfall when the precipitation would help disperse their scent, and the noise would mask any sounds they couldn’t avoid making. Despite these precautions, the approach to the sniper school was the most challenging operation of Davis’s career. Twice they narrowly avoided detection by German patrols accompanied by shepherds specifically trained to alert to human presence.

Once Davis remained motionless for over 14 hours after a German observer established a position less than 20 yard from his location. Finally, on April 17th they located the sniper school, a former hunting lodge nestled in a valley surrounded by excellent vantage points. Through careful observation, they identified General Wolf and mapped the facility’s daily routines.

Approximately 40 student snipers were in training along with 10 instructors, all experienced veterans of the Eastern Front. What made this target particularly challenging was that every person at the facility was a trained observer, specifically alert to the very techniques Davis and his team were using.

Additionally, Wolf had implemented a complex security system with overlapping fields of observation, specifically designed to detect even the most subtle disturbances in the natural environment. After 2 days of observation, Davis formulated his plan. Rather than attempting to eliminate the entire facility, which would have been beyond their capabilities, they would focus on neutralizing Wolf and destroying the facility’s training materials, particularly the documentation of Davis’s techniques that Wolf had compiled. The operation was set for the pre-dawn hours of April 20th.

Using the cover of a thunderstorm that rolled through the mountains that night, the team moved into position around the facility. Davis himself approached the lodge from what appeared to be the most heavily guarded direction. A counterintuitive choice that bypassed Wol’s expectations.

At precisely 0400 hours, Davis eliminated the two guards at the main entrance with suppressed shots that were masked by thunderclaps. The team then infiltrated the building while Cooper and two others maintained overwatch positions covering potential escape routes.

Inside, Davis located Wolf’s office and the adjacent room containing training materials. While the rest of his team planted explosives at key structural points, Davis discovered something unexpected. A comprehensive analysis of his own techniques, including detailed observations and methodologies for countering them.

Wolf had studied him as intently as a naturalist might study a new species, documenting patterns and behaviors with scientific precision. As Davis gathered these materials, a noise from the doorway alerted him to Wolf’s presence. The elderly general stood watching him. A Luga pistol held casually at his side. “So, you are the ghost,” Wolf remarked in accented English. “I have been studying you for months.

Your techniques are remarkable, a perfect synthesis of indigenous knowledge and modern application.” Davis maintained his position, rifle at the ready, but not yet raised. “You’ve killed a lot of good men with that knowledge. Wolf inclined his head slightly. As you have killed many of mine, it is the nature of our profession.

But I must admit, your methods represent something truly innovative. In another time, we might have had much to discuss. The war is almost over, General. Germany has lost. There’s no need for more death. Perhaps, Wolf acknowledged, but I have my duty as you have yours. The moment hung suspended between them, two master hunters recognizing each other’s skill across the divide of conflict.

Then, with a speed belying his age, Wolf raised his pistol. Davis fired once. The general collapsed, a look of professional appreciation rather than surprise on his face as he fell. The team completed their mission, destroying the training facility and all documentation of Davis’s techniques before withdrawing into the mountains. The explosion was attributed to partisan activity and the true nature of the operation remained classified for decades afterward.

By the time Germany surrendered on May 8th, 1945, Davis’s special reconnaissance detachment had accounted for over 500 confirmed eliminations of German snipers, observers, and high value targets. An extraordinary record that would influence military doctrine for generations to come. In the immediate aftermath of the war, Davis received the Distinguished Service Cross for his actions, the second highest military decoration for extraordinary heroism in combat.

The citation carefully avoided specific details of his methods, referring only to exceptional skill in counter sniper operations and innovative techniques that significantly reduced Allied casualties. The true nature and extent of Davis’s contributions remained classified for decades, partly due to ongoing Cold War applications of his techniques, and partly due to the reluctance of military historians to fully acknowledge the contributions of African-American soldiers during World War II.

Upon returning to civilian life, Davis faced the painful irony common to many black veterans, having fought for freedom abroad, only to return to segregation and discrimination at home. Nevertheless, he established a small but successful hunting guide service in Northern Michigan, where his extraordinary skills continued to impress clients who never knew the full extent of his wartime accomplishments.

In 1948, when President Truman signed Executive Order 9981, officially desegregating the armed forces, Davis was invited to Fort Benning to consult on the development of new sniper training protocols. Many of the techniques he had pioneered during the war were incorporated into the curriculum, though often without proper attribution.

It wasn’t until 1977, more than three decades after the war, that Davis received full recognition for his contributions when previously classified documents were released. Military historians were astonished to discover the extent of his influence on modern camouflage and counter sniper techniques.

Professor Robert Hamilton of the Army War College wrote, “Davis’s methods represented a paradigm shift in concealment philosophy. Rather than focusing on hiding from the enemy, he developed techniques to be seen without being recognized, a psychological approach that proved devastatingly effective against conventional military doctrine. Davis’s legacy lives on in modern special operations training, where his indigenous derived techniques continue to influence how elite units approach concealment and counter sniper operations.

The fundamental principle he articulated, understanding how your adversary perceives the world and using that understanding to become something they expect to see, remains as relevant in contemporary warfare as it was on the hedge of Normandy. James Monroe Davis passed away in 1992 at the age of 71. His obituary in the New York Times noted that his specialized unit was credited with saving thousands of American lives through their elimination of German observation posts and sniper positions. General Colin Powell, then chairman of

the Joint Chiefs of Staff, issued a statement acknowledging Davis as one of the unsung heroes whose innovative thinking helped shape modern special operations capabilities. Perhaps the most fitting tribute came from William Cooper, who had served alongside Davis from those first pre-Day operations through the end of the war.

In an interview for a military history documentary in 1985, Kooper reflected, “What made Davis special wasn’t just his skill with a rifle or even his remarkable camouflage technique. It was his way of thinking, his ability to see the battlefield from the enemy’s perspective, and use that understanding to become invisible in plain sight.

The Germans never imagined a black soldier from Mississippi using Creek Indian hunting methods would become their most formidable adversary. That’s the greatest camouflage of all. Not hiding from what others might see, but challenging what they can imagine. Today, specialized units around the world study Davis’s techniques, often unaware of their true origin. The ghost who walked the hedgeros of Normandy continues to influence modern warfare.

A testament to how ancient wisdom applied with innovative thinking can prove more effective than the most sophisticated technology. The story of James Monroe Davis reminds us that innovation often comes from unexpected sources and that sometimes the most valuable knowledge is not created in research laboratories or militarymies but passed down through generations of people whose survival depended on understanding the fundamental principles of nature and perception.

In the complex theater of modern warfare, this lesson remains as relevant as ever. that sometimes the most effective way to avoid being seen is not to hide, but to transform how others see.

News

CH2 90 Minutes That Ended the Luftwaffe – German Ace vs 800 P-51 Mustangs Over Berlin – March 1944

90 Minutes That Ended the Luftwaffe – German Ace vs 800 P-51 Mustangs Over Berlin – March 1944 March…

CH2 The “Soup Can Trap” That Destroyed a Japanese Battalion in 5 Days

The “Soup Can Trap” That Destroyed a Japanese Battalion in 5 Days Most people have no idea that one…

CH2 German Command Laughed at this Greek Destroyer — Then Their Convoys Got Annihilated

German Command Laughed at this Greek Destroyer — Then Their Convoys Got Annihilated You do not send obsolete…

CH2 Why Bradley Refused To Enter Patton’s Field Tent — The Respect Insult

Why Bradley Refused To Enter Patton’s Field Tent — The Respect Insult The autumn rain hammered against the canvas…

CH2 Germans Couldn’t Stop This Tiny Destroyer — Until He Smashed Into a Cruiser 10 Times His Size

Germans Couldn’t Stop This Tiny Destroyer — Until He Smashed Into a Cruiser 10 Times His Size At…

CH2 When a Canadian Crew Heard Crying in the Snow – And Saved 18 German Children From Freezing to Death

When a Canadian Crew Heard Crying in the Snow – And Saved 18 German Children From Freezing to Death …

End of content

No more pages to load