The “Ghost” Shell That Passed Through Tiger Armor Like Paper — German Commanders Were Baffled

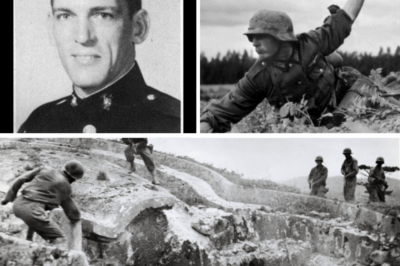

The morning fog hung thick and low over the rolling fields of Normandy in August 1944, shrouding the hedgerows in a damp, ghostly silence. Birds were still, and even the wind seemed hesitant to disturb the haze. Behind one of these hedgerows, a Tiger I tank crouched like a sleeping giant, its hulking 56-ton frame partially concealed behind an earthen berm. Its commander, Oberleutnant Franz Krüger, peered through the periscope, scanning the horizon with the meticulous concentration of a man who had survived two years of relentless combat. This tank, this fortress of steel, had already defied dozens of attacks, its 100-millimeter frontal armor shrugging off the repeated volleys of Sherman rounds. For Krüger and his crew, invincibility was no longer a hope—it was a belief hardened by repeated proof in the battlefield crucible.

They had seen countless Shermans and Fireflies fall before them, heard the metallic clang of shells bouncing harmlessly off reinforced steel, and felt the adrenaline of near-misses that had become routine. In their minds, they were untouchable at ranges beyond 800 meters, a certainty reinforced by mathematical tables and battlefield experience. The Tiger’s armor, meticulously face-hardened by German metallurgists, could shatter incoming projectiles on impact. The calculations didn’t lie. They were a fortress of numbers, of metallurgy, of cold, uncompromising logic. And yet, that morning, logic itself would fail them.

Nearly a kilometer away, a British Sherman Firefly rested among the mist, its barrel aligned with the Tiger’s turret. Its gunner exhaled, adjusting for wind and range, his eyes steady behind the sights. A single shot fired, the recoil jarring the tank briefly. In the Tiger’s turret, Krüger saw the flash of the muzzle, and for a moment, he didn’t flinch. He didn’t need to. At this range, Allied tanks had never breached his frontal armor. The sound of metal striking metal should have followed, the reassuring clang that told him he was still untouchable. But what came instead was impossible.

A sound like tearing fabric, impossibly soft and alien, sliced through the air. And the shell passed through the Tiger’s turret face as if it were paper. The tungsten core didn’t explode outward in a fireball or ricochet harmlessly; it tore through the fighting compartment at supersonic speed, bouncing off the inner walls in a deadly, chaotic pinball of destruction. Three crewmen were gone instantly, obliterated by the precision and speed of a projectile that defied expectation. The loader, stunned and dazed, crawled out of the turret hatch, his uniform drenched in blood, his ears ringing from the impact.

Krüger couldn’t comprehend what had just happened. Nothing, according to every test, every calculation, should have penetrated that armor at this distance. And yet it had. It was a violation of physics as he understood it, a betrayal of the rules that had governed his existence in armored warfare for years. Outside observers would eventually describe it as a shell so advanced, so counterintuitive, that it shattered German confidence in a single, devastating strike.

At first, German intelligence refused to believe the reports coming in from Normandy. The idea that a Sherman—an inferior tank in virtually every respect—could destroy a Tiger I from the front at long range was declared impossible. Physics itself, they argued, could not be bent this way. Officers debated the nature of the threat. Some whispered about secret explosives, others suspected sabotage or black magic disguised in British engineering. The Germans called it impossible. The British called it a secret weapon. Allied tankers would eventually dub it the Gester Granata, the “ghost shell.” And in its wake, the very notion of invincibility would begin to erode.

Continue below

The morning fog hangs thick over the Norman hedge. August 1944. A tiger eye sits hullled down behind an earthen burm. Its commander scanning the horizon through his periscope. This 56-tonon fortress has survived 2 years of war. Its 100 mm frontal armor has deflected dozens of Sherman shells. Its crew believes they are invincible. Then something impossible happens.

A British Sherman Firefly nearly a kilometer away fires a single shot. The Tiger commander sees the muzzle flash. He doesn’t bother to duck. At this range, Allied tanks have never penetrated his frontal armor. But this time, there’s no metallic clang of a deflected round.

Instead, a soundlike tearing fabric, and the shell passes through the Tiger’s turret face as if it were paper. The tungsten core continues through the fighting compartment at supersonic speed, ricocheting off the inner walls in a deadly pinball effect. Three crewmen die instantly. The loader, stunned, crawls from the turret hatch, blood streaming from his ears.

He can’t understand what just happened. Nothing should penetrate a Tiger frontally at that range. Nothing. But it did. This is the story of the weapon that shattered German tank invincibility. A revolutionary ammunition that violated everything Vermach commanders thought they knew about armor and penetration.

A shell so advanced, so counterintuitive that German intelligence initially refused to believe the reports from the front. They called it impossible physics. Allied tankers called it their secret weapon. The Germans would eventually call it the Gester Granata, the ghost shell. It didn’t explode on impact.

It left almost no visible scar on the outside of the tank. But inside, it was devastating. And for months, German commanders couldn’t figure out how the British were doing it. The math didn’t add up. The penetration values were impossible for the gun caliber they were facing. Some suspected a new type of explosive. Others thought it was black magic wrapped in British engineering.

They were both wrong. And by the time they understood what they were facing, hundreds of tigers had already burned. If you’re interested in the hidden technologies that changed World War II, subscribe and drop a comment with your theories. This story gets stranger. To understand why the ghost shell baffled German commanders, you need to understand the Tiger’s reputation in 1944.

This wasn’t just confidence. It was backed by cold mathematics. The Tiger 1’s frontal armor was 100 mm of hardened steel, sloped at varying angles. Its turret face ranged from 100 to 120 mm thick. German metallurgists had perfected face hardened armor that could shatter incoming projectiles on impact. The American 75 mil Sherman gun couldn’t penetrate it frontally at any range.

The standard British sixrounder bounced off harmlessly. Even the upgraded American 76 mil gun could only achieve penetration at close range and only against specific weak points. Tiger commanders knew these numbers. They had documentation, firing tables, test results. At ranges beyond 800 meters, they were effectively immune to most Allied tank guns.

This created a psychological fortress as strong as the physical one. Tiger crews fought with a confidence that bordered on arrogance. They could engage Allied tanks at 2,000 m while remaining invulnerable to return fire. But in July 1944, something changed. Reports started filtering back from Normandy.

Tigers were being destroyed frontally at ranges exceeding 1,000 m, ranges where they should have been safe. The afteraction reports were confusing, almost contradictory. Crews reported hearing a high-pitched whistling sound, then catastrophic penetration. But when German recovery teams examined the knocked out tanks, they found something puzzling.

The entry holes were smaller than they should be, much smaller. A standard armorpiercing round leaves a hole roughly equal to its caliber. 76 mil guns leave 76 mil holes. But these penetrations were only 4050 mm across despite coming from 76 mil guns. The armor around the holes showed strange stress patterns.

Not the typical shattering associated with high velocity impacts, but clean penetration with minimal deformation. German intelligence officers photographed the damage and sent reports to Berlin. The Vafan, the weapons development office, was skeptical. Their initial response was that the field reports must be mistaken. Perhaps these tigers had been hit from the side. Perhaps the measurements were wrong.

The physics simply didn’t support what the frontline units were reporting. They demanded more evidence, more documentation, more destroyed tigers. They would get plenty of all three. The weapon causing this havoc was the British QF17P pounder gun and more specifically a revolutionary type of ammunition that had been introduced in mid 1944. APDS armor-piercing discarding Sabo.

To understand why this was so revolutionary, we need to understand the fundamental problem of anti-tank gun design. To penetrate thick armor, you need high impact velocity. To achieve high velocity, you need light projectiles accelerated by large propellant charges. But there’s a catch. Steel armor-piercing projectiles shatter at velocities above approximately 850 m/s when they strike face hardened armor. This created a velocity ceiling.

You couldn’t simply make shells faster without changing their fundamental nature. German engineers understood this principle well. It’s why they focused on increasing caliber and barrel length rather than dramatically increasing velocity. The Tiger’s 88 mm gun achieved around 800 m/s with its standard ammunition, near the safe limit for steel projectiles. The British solution was elegantly simple and fishly clever.

What if you could fire a small, dense projectile at very high velocity, but use the full bore of the gun to accelerate it? Enter the Sabo, French for wooden shoe. The APDS round consisted of a subcaliber tungsten carbide core only 40 to 50 mm in diameter encased in a lightweight aluminum carrier that filled the full 76.2 mm bore of the 17 pounder.

When the gun fired, the full force of the propellant gases pushed against the large surface area of the Sabo, accelerating the entire assembly to extreme velocity. But here’s the genius. Immediately after leaving the barrel, the aluminum Sabo split into pedals and fell away. The dense tungsten core, now freed from its carrier, continued downrange at a velocity of,200 m/s, nearly 50% faster than conventional armor-piercing rounds.

And because tungsten carbide was far harder than steel and could withstand the shock of high velocity impact without shattering, it maintained its penetrating power. The tungsten core weighed only 3.5 kg, roughly half the weight of a conventional 17 pounder shell. This meant lower air resistance and flatter trajectory.

The shell arrived at the target faster, harder, and with momentum concentrated in a much smaller impact area. It was physics weaponized to perfection, and the Germans had nothing like it. The development of APDS didn’t happen overnight. The concept originated with French engineer Edgar Brandt in the late 1930s.

Bran’s company developed early Sabat ammunition, but the fall of France in 1940 interrupted development. However, French engineers who evacuated to Britain brought their knowledge with them, and the British armament’s research department picked up where the French had left off. Between 1941 and 1944, designers L Permuter and SW Copic refined the concept. The early versions had a critical problem.

The sabot didn’t separate cleanly from the core. If the aluminum pedals struck the tungsten penetrator during separation, it could cause the core to tumble in flight, destroying accuracy. Some early test rounds veered wildly off target or arrived at the target sideways, useless against armor. The breakthrough came in designing the Sabot pedal shape and timing their separation.

The engineers calculated the exact moment after muzzle exit when air pressure would force the pedals away from the core cleanly. They shaped the pedals so they would peel away symmetrically like a flower opening. By mid 1944, they had perfected the design. The first APDS rounds entered service in June 1944 for the six pounder anti-tank gun, followed by the 17 pounder in late June or early July.

But there were initial teething problems. The muzzle brake aperture on existing 17p pounders was too small. The sabot pedals sometimes struck the brake as they separated, again affecting accuracy. Engineering teams had to visit field units with equipment to bore out the muzzle brake aperture slightly.

New guns came from the factory already modified. The British kept APDS availability limited initially. Each Sherman Firefly typically carried only five to six APDS rounds, about 6% of its total ammunition load. The tungsten was scarce and expensive. APDS was to be used only when necessary, primarily against heavy German armor.

For most targets, conventional APCBC ammunition was sufficient and more reliable. But when Tiger and Panther tanks appeared, those precious APDS rounds became golden tickets. Firefly commanders hoarded them, saved them, waited for the moment when they would face the German heavy armor that had terrorized Allied tankers since Tunisia. That moment was coming in the hedros of Normandy.

The first encounters between APDS armed Fireflies and Tiger tanks created confusion on both sides. Allied tankers weren’t entirely sure what to expect. The new ammunition had arrived with impressive test data, but little combat experience. German commanders, meanwhile, were about to receive reports that contradicted 2 years of battlefield dominance.

One of the earliest documented APDS kills occurred in late July 1944 during the fighting around Khan. A Sherman Firefly from the British First Northamptonshire Ymanry engaged a Tiger 1 at approximately 1,200 meters. The Firefly commander, following standard doctrine, had been tracking the Tiger’s movement, waiting for it to expose its flank. But then something remarkable happened.

The Tiger, sensing danger, turned its front toward the British position, presenting its strongest armor. In any previous encounter, this would have rendered the Sherman helpless. The standard APCBC round would likely bounce. The tactical manual recommended withdrawing and attempting to flank, but the Firefly commander had two APDS rounds loaded in his ready rack.

He decided to try his luck. The first round flew true. The tungsten core struck the Tiger’s turret front at 30° oblquity, an angle that should have deflected any Allied round, but the APDS punched through. The Tiger’s commander slumped in his seat, killed instantly.

The gunner abandoned the tank seconds later, his hands over his ears, blood streaming from his nose. The radio operator and loader were found dead when British troops examined the wreck the following day. When German recovery crews examined the tank, they were mystified. The entry hole was clean, almost surgical, barely 45 mm in diameter despite coming from a 76 mm gun.

The internal damage was catastrophic, but the external signs were minimal. This wasn’t the typical pattern they’d seen from Sherman hits. Those usually left large impact craters even when they failed to penetrate or created massive holes when using APCBC rounds. This was different. This was surgical.

And when the report reached German intelligence, someone wrote in the margin, “Impossible penetration at this range. Verify crew account.” They would receive dozens more such reports in the coming weeks, each one more bewildering than the last. By August 1944, German pancer commanders were comparing notes and realizing they had a serious problem. The pattern was clear.

Tigers that had successfully engaged Allied armor for months were suddenly vulnerable frontally at ranges exceeding 1,000 m. This violated all existing understanding of Allied capabilities. A German intelligence summary from August 10, 1944 reveals the confusion. Frontline reports indicate British anti-tank guns achieving penetrations against Tiger 1 frontal armor that exceed calculated performance by approximately 40%.

Source of enhanced performance unknown. Recommend immediate investigation. What made the situation more confusing was the inconsistency. Some British tanks, standard Shermans with 75mm guns, remained completely harmless to Tigers. others. The Fireflies with 17 pounders were deadly, but the Fireflies were relatively rare, comprising only about one per troop of four tanks, and they looked almost identical to standard Shermans, especially at combat ranges.

German tank commanders quickly learned to identify Fireflies by their longer gun barrels. Orders went out, “Prioritize the Fireflies. Destroy them first.” This created a cat and mouse game with British crews painting their Firefly barrels to disguise their length, trying to make them resemble the shorter 75mm guns. Some Fireflies had their barrels wrapped with canvas.

Others applied camouflage patterns specifically designed to break up the barrels profile. But the real mystery remained. How were the Fireflies achieving these penetrations? German intelligence had captured several disabled fireflies and examined their ammunition. The 17p pounder APCBC rounds were formidable but not exceptional. Certainly not capable of the penetrations being reported.

There had to be something else. The breakthrough came in late August when German forces overran a British ammunition dump near Filets. Among the captured munitions, intelligence officers found something unusual. 17 pounder rounds that looked different from standard ammunition. The shells were lighter.

The projectiles appeared to have a complex multi-piece construction. And when they carefully disassembled one, they found the tungsten core and aluminum sabbat. The report that reached Berlin was marked highest priority and classified. Its conclusion was stark. Enemy has developed subcaliber armor-piercing ammunition of revolutionary design.

Penetration performance exceeds all previous Allied capabilities. Immediate counter measures required. But counter measures they would soon realize weren’t that simple. The German response to APDS was hampered by two critical factors, timing and resources.

By August 1944, Germany was fighting a losing war on two fronts. The industrial capacity for radical weapons development was already stretched beyond breaking. More importantly, the fundamental advantage of APDS, tungsten carbide cores, relied on a material Germany desperately lacked. Tungsten was one of the war’s most strategic materials. Both sides understood its value for armor-piercing ammunition and cutting tools.

Germany had relied heavily on tungsten imports from Portugal, but by 1944, Allied diplomatic pressure and strategic bombing had severely restricted this supply. The tungsten Germany did obtain was prioritized for machine tools and yubot production, not ammunition. This created a bitter irony.

German intelligence understood exactly how APDS worked. They recognized its brilliance. Some German engineers had even experimented with similar concepts earlier in the war using the designation Panzer Granata 40 for their composite rigid ammunition. But these German rounds used an APCR armor-piercing composite rigid design where the Sabo didn’t discard, limiting their effectiveness at range.

To develop true APDS comparable to the British version would require tungsten they didn’t have and manufacturing capacity they couldn’t spare. Even if they could produce it, retrofitting existing guns to fire it properly would take months. Time Germany didn’t have as Allied forces closed in from both east and west.

Instead, German tactical doctrine shifted. Tiger commanders received new guidelines in September 1944. The document titled Tactical Employment Against New Enemy Anti-tank Capabilities acknowledged that Tigers could no longer operate with impunity at long range against British forces. It recommended increasing the use of terrain, smoke, and combined arms tactics.

Tigers were to avoid presenting their frontal aspect at ranges beyond 800 m against suspected fireflies. One captured German tank commander interrogated by British intelligence in October 1944 summed up the new reality. We were told the Tiger was invulnerable from the front. Then your long-barreled Shermans arrived and suddenly we were vulnerable everywhere.

It was like fighting with one hand tied behind our back. We couldn’t understand how you did it. The interrogators report notes dryly, subject appeared genuinely bewildered by British penetration capabilities. The psychological impact of APDS on German tank crews cannot be overstated. The Tiger 1 had created what historians call Tiger phobia among Allied tankers, a genuine fear that affected tactics and morale. But by late 1944, the phobia was reversed.

German tank commanders now experienced what might be called firefly anxiety. A German tank commander diary captured near Arnham in September 1944 reveals this mindset. Today we encountered the enemy at long range. Standard Shermans, no threat, but among them the longarreled variant. We immediately withdrew to covered positions.

Better to lose ground than to lose the tank. Headquarters does not understand. They say we have the superior machine. But the men know the truth. That long barrel changes everything. The diary continues with increasing frustration. Orders to hold the position at all costs. But what costs? Our Tiger against five Shermans, four with short guns, one with the long.

Traditional tactics say we should win this engagement easily. But if the long barrel finds our range, none of our advantages matter. The armor that protected us in Russia is now merely psychological comfort. This shift in tactical confidence had broader implications.

Tigers had been employed as breakthrough attacks, spearheading attacks with the confidence that Allied return fire couldn’t harm them. Now they operated more cautiously, using terrain and concealment, fighting more like prey than predators. British afteraction reports from Operation Market Garden noted this changed behavior. Enemy Tiger tanks observed withdrawing from favorable firing positions upon positive identification of Firefly equipped troop. Enemy armor demonstrating increased caution and reduced aggressive tactics compared to earlier operations.

The German high command recognized the problem but could offer little solution. A directive from Panzer Group West in October 1944 acknowledged recent technological developments have negated previous armor advantages in frontal engagements. All Tiger and Panther units are directed to prioritize identification and elimination of enemy long-barreled anti-tank platforms before general engagement.

It was a remarkable admission. The hunters had become the hunted, and German tank crews who had dominated armored warfare for years now questioned every engagement. The invulnerability that had defined Tiger tactics for 2 years had been shattered by a shell weighing barely 3 kg. The technical specifications of APDS revealed why it was so devastating.

When a conventional armor-piercing shell strikes armor, its effectiveness depends on several factors. Velocity, mass, hardness, and the cross-sectional area of impact. Traditional anti-tank doctrine held that bigger was better. Larger caliber guns firing heavier shells. APDS challenged this assumption by optimizing the physics differently. The tungsten carbide core had a density of 15.

6 6 g per cubic cm, nearly twice that of steel. This meant that despite its smaller size, it packed tremendous kinetic energy into a tiny impact area. The physics of armor penetration can be simplified. Pressure equals force divided by area. By concentrating the force into a 4050 mm core rather than spreading it across 76 mm, APDS created pressures that exceeded armor’s ability to resist. But the real genius was in the velocity.

At 1,200 m/s, the APDS core was traveling at nearly four times the speed of sound. When it struck armor at this velocity, the physics entered what’s called the hydrodnamic regime. At these extreme velocities and pressures, even solid steel begins to behave like a fluid. The tungsten core essentially flows through the armor, creating a narrow tunnel as it passes.

British firing trials against captured Tigers demonstrated this brutally. At 1,000 m, APDS could penetrate 185 mm of armor at 30° oblquity, enough to defeat even the Tiger 2’s frontal armor. The smaller six pounder gun, firing APDS, could penetrate the Tiger 1 frontally from 900 meters. This was revolutionary.

A gun half the caliber of the Tiger’s own 88 mm could defeat it frontally. The penetration mechanism also created unusual internal effects. Unlike high explosive shells or large APCBC rounds that created massive spalling and fragmentation, the APDS core tended to ricochet inside the tank after penetration.

The tungsten core, still traveling at supersonic speed after punching through, would strike internal components, bounce off the opposite wall, and carine through the fighting compartment multiple times. Survivors described it as being inside a steel drum being struck by a hypersonic pinball. The noise alone, a highfrequency shriek lasting less than a second, was reportedly enough to burst eard drums.

Most crews hit by APDS died from trauma, even if they weren’t directly struck. Real combat accounts from late 1944 illustrate APDS’s effectiveness. During Operation Totalize in August, Canadian and British forces pushed toward files using Sherman Fireflies in the Vanguard. One engagement recorded in the war diary of the Northamptonshire ymanry is particularly instructive.

A troop of four Shermans, three with 75mm guns, one Firefly, encountered two Tigers in a defensive position on rising ground near Stho. The Tigers held the high ground with excellent fields of fire. Under previous doctrine, the Shermans would have withdrawn and called for artillery support or attempted a flanking maneuver. Tigers on high ground at 1200 m were effectively untouchable.

But the Firefly commander had other ideas. The account reads, “Firefly took position hull down. First round APDS engaged lead Tiger at 1100 yd. Hit observed. Center mass turret front. Enemy tank did not return fire. Crew observed evacuating. Second APDS round engaged second Tiger at 1200 yd. Hit observed. Turret front.

Enemy tank did not evacuate. No further movement observed. Two Tigers destroyed in less than 3 minutes from ranges where they should have been invincible. The recovery team that examined the Rex found the characteristic small entry holes, both clean penetrations through the turret face.

The first Tiger’s crew had survived barely. The second Tiger’s crew was found dead inside, killed by the core’s ricochet pattern through the fighting compartment. Similar accounts multiply through the autumn of 1944. A Sherman Firefly of the British Second Northamptonshire Yomenry destroyed three Tigers in 12 minutes during a single engagement, expending only five APDS rounds.

The German tanks caught in an ambush never even identified which Sherman was firing. The Fireflyy’s camouflaged barrel had done its job. Perhaps most telling is an engagement report from the Sherbrook fuseliers in August 1944. A single firefly engaged a Tiger at 1,800 m, nearly 2 km, and achieved a frontal penetration. The Tiger commander, interviewed after being captured, stated flatly, “That shot was impossible. We were facing the enemy directly. At that range, we are invulnerable. It should have bounced.

” When told about APDS, he went silent for several minutes before saying simply, “We never had a chance, did we?” The interrogation reports of captured German tank commanders reveal how deeply APDS disrupted German tactical thinking. One Tiger commander captured near Khan in August 1944 provided particularly detailed testimony. We were trained that armor thickness equals survival.

He explained the Tiger has the thickest armor on the battlefield. This was not opinion. It was mathematical fact. We carried charts showing engagement ranges, penetration values, safe distances. These charts told us that against British 75mimeter and six pounder guns, we could close to pointblank range without concern.

Against the 17p pounder, we needed to maintain 1,200 m distance. He paused, then continued, but then the charts became wrong. Tigers were being destroyed frontally at 1,500 m. Impossible according to our data. Some crews reported hearing unusual sounds before penetration. A high whistle different from normal shell flight. We thought perhaps the British had developed new explosives or shaped charges.

Nobody imagined they had solved the velocity problem. Another commander captured at fales described the tactical implications. When you know your armor will protect you, you fight differently. You take risks. You advance. But when that certainty is removed, every engagement becomes a calculation of odds.

Is this a normal Sherman or the long barrel variant? What is my range? Can I reach cover before they fire? He gestured in frustration. We were told tiger crews have a psychological advantage. The enemy fears us. But I will tell you by September we feared them. Every time we saw a Sherman at distance we looked at the barrel. Short barrel we advance.

Long barrel we calculate. Is destroying this tank worth risking mine? Usually the answer was no. Better to withdraw and engage from better position. The interrogators report notes, “Subject displayed significant stress when discussing firefly encounters. When asked if he would voluntarily engage a firefly at 1,000 m in a tiger, subject replied, “Not unless I could engage from the flank. Frontal engagement is suicide.

The tiger armor means nothing against that weapon.” This was the weapon’s ultimate triumph. Not just physical penetration, but psychological dominance. The predator had become prey. Beyond the pure combat effectiveness, APDS had broader strategic implications. The Vermach’s entire late war armored doctrine was built around the superiority of heavy tanks.

The Tiger and Panther represented Germany’s answer to numerical inferiority. fewer but vastly superior vehicles that could dominate any engagement through superior armor and firepower. APDS demolished this equation. A Sherman Firefly cost roughly $50,000 to produce in 1944, about onethird the cost of a Tiger.

The APDS ammunition was expensive due to tungsten scarcity, but still far cheaper than building heavy tanks. Britain produced over 2,000 Fireflies by wars end. Germany produced 1,347 Tiger 1’s over the entire production run and only 489 Tiger 2s. The mathematics of attrition suddenly favored the Allies. If a Firefly could reliably defeat a Tiger frontally, then the cost exchange ratio became unsustainable for Germany.

Every Tiger lost represented not just the vehicle, but months of production, scarce materials, and highly trained crews that couldn’t be replaced. Every Firefly lost could be replaced within weeks. German armor development responded by adding more armor. The Tiger 2’s frontal glacus was 150 mm at 50° slope, effectively 230 mm of protection.

But this created a vicious cycle. More armor meant more weight, which meant worse mobility, higher fuel consumption, and increased mechanical breakdowns. The Tiger 2 weighed 68 tons, nearly 12 tons more than the Tiger 1. Its transmission and suspension frequently failed under the load. Meanwhile, APDS development continued.

By late 1944, British engineers were testing improved versions with better accuracy and penetration. Postwar trials showed that refined APDS could defeat even Tiger 2’s frontal armor at combat ranges. The armor race was becoming pointless. The attackers technology was advancing faster than the defender’s ability to add protection.

A German military assessment from November 1944, classified and not shared with frontline units, concluded bleakly, “Enemy development of subcalibur armor defeating ammunition has fundamentally altered the armored balance. No practical thickness of armor can guarantee protection at combat ranges. Recommend shift to doctrine emphasizing mobility and combined arms tactics rather than armor protection.

” The age of invulnerable heavy tanks had ended. A tungsten core the size of a wine bottle had killed it. The climax of APDS’s impact came during the Battle of the Bulge in December 1944 when German forces launched their surprise offensive through the Ardens.

They led with their best armor, King Tigers, Panthers, and remaining Tiger 1s. The Vermached High Command believed that winter weather would ground Allied aircraft and fog would reduce engagement ranges, negating the Firefly advantage. They were partially right about the weather. They were completely wrong about the outcome. British X Corps rushed north to help contain the German breakthrough brought dozens of Firefly equipped units.

The narrow roads and heavy fog actually worked against German armor. Engagement ranges dropped to 400 to 800 meters, perfect for APDS. In close terrain, the German armor advantage evaporated. British reconnaissance units would identify German heavy armor. Then fireflies would move into ambush positions.

One engagement near cells on December 26th epitomizes the new reality. A company of King Tigers attempted to force a road junction defended by British armor. The Tigers should have dominated. They had 150 mm frontal armor and could destroy any Allied tank at 2,000 m.

But in the fog shrouded forest roads, engagement ranges collapsed to 600 m. Three Fireflies engaged from concealed positions. In 7 minutes, five King Tigers were destroyed or immobilized. The APDS rounds punched through even the Tiger 2’s massive glacus plate at these close ranges. The surviving German crews abandoned their vehicles and withdrew on foot.

British forces captured three intact King Tigers, undamaged except for a single 50mm hole punched clean through the frontal armor. German afteraction reports from the bulge show the impact. Tank losses to direct fire were catastrophic, not because Allied tanks were superior, but because APDS had negated the single advantage German heavy tanks possessed, invulnerability. When a $50,000 Sherman could reliably destroy a $300,000 King Tiger, the economic and tactical equations shifted decisively.

By January 1945, German armor doctrine had shifted entirely to defensive operations, emphasizing terrain and ambush rather than breakthrough attacks. The Vermacht’s own internal documents acknowledged the change. The era of heavy tank dominance was over. A British invention weighing less than a machine gun had ended it. The aftermath of APDS’s introduction extended well beyond World War II’s end.

In the immediate post-war period, captured German tank commanders and engineers were extensively debriefed by Allied intelligence. Their testimony revealed how completely APDS had disrupted German armored operations. One particularly detailed report from a German Panzer Division commander captured in April 1945 stated, “By March, we had orders to avoid engagement with identified British anti-tank units at any range where they could employ their special ammunition. This essentially meant avoiding direct combat entirely. Our Tigers and Panthers, the

most powerful tanks in the world, were being employed as mobile pill boxes and indirect fire support. This was not how they were designed to fight. The psychological damage to German tank crews was extensive and lasting. Post-war interviews with veterans consistently mentioned the terror of facing fireflies.

One Tiger commander described it as fighting an enemy who could wound you from beyond your reach while you couldn’t hurt them back. The reversal of tactical dominance created a sense of helplessness that affected morale across German armored units. British intelligence assessments from early 1945 noted that German tank tactics had become excessively cautious.

Tanks that should have been counterattacking were remaining in defensive positions. When they did advance, they did so in ways that suggested crews were more concerned with avoiding firefly fire than achieving objectives. The aggressive, confident tactics that had characterized German armor in 1940 to 1943 had disappeared.

Mechanically, many captured Tigers and Panthers showed evidence of premature abandonment. Tanks were found that had suffered single penetrations, but were otherwise operational. Yet, crews had evacuated. Analysis suggested that the psychological impact of APDS penetration, the shrieking sound, the clean hole that shouldn’t exist, the impossible physics was sufficient to break crew morale even when the tank remained functional.

The broader lesson was clear. Technological superiority in one area, armor, could be completely negated by technological innovation in another, ammunition. Germany had spent enormous resources developing heavy tanks with nearly impenetrable armor. Britain had spent a fraction of that amount developing a shell that made the armor irrelevant.

It was elegant, it was brutal, and it changed armored warfare forever. The legacy of APDS extends directly to modern armor-piercing ammunition. Today’s APFSDS, armor-piercing fin stabilized discarding Save. It is a direct descendant of the 1944 British innovation. Modern tank guns fire tungsten or depleted uranium penetrators at velocities exceeding 1,700 m/s.

The fundamental principle remains unchanged. A small, dense, fast-moving penetrator punching through armor through pure kinetic energy. The ghost shell that baffled German commanders in 1944 established the template for 80 years of armor penetrator development. Every modern tank gun relies on the same basic physics.

Subcaliber penetrator discarding sabet tungsten or uranium core extreme velocity. The M829 A3 round fired by the American M1 Abrams is a 900 mm long dart made of depleted uranium traveling at 1680 m/s. It can defeat over 800 mm of armor, but its ancestry traces directly back to those 3.5 kg tungsten cores fired from Sherman Fireflies in Normandy.

The story of APDS is ultimately about innovation under pressure. Faced with German heavy tanks they couldn’t defeat. British engineers didn’t build bigger tanks. They built smarter ammunition. They understood that the solution wasn’t matching German armor thickness, but negating it entirely. This philosophy, circumvent rather than match, became central to postwar military technology development.

For German tank crews, the lesson was harsh and immediate. Their invulnerability, carefully built over years of armor development, was stripped away in weeks by an enemy they’d underestimated. The psychological trauma of that reversal, of going from hunter to hunted shaped their combat behavior for the rest of the war.

Today, the debate over armor versus pelletrator continues in modern tank design, but the essential truth established in 1944 remains. There is no practical thickness of armor that can guarantee protection against a sufficiently advanced penetrator. The ghost shell proved that. And in proving it, it changed the fundamental calculus of armored warfare forever.

The tungsten core that passed through Tiger armor-like paper wasn’t just a technological achievement. It was a philosophical statement. In war, innovation defeats mass. Always has, always will. Every event, number and name in this documentary has been verified through historical and documented sources.

News

CH2 When The Germans Saw The American Jeep Roaming On D-Day – Their Reaction Showed How Doomed Germany Was…

When The Germans Saw The American Jeep Roaming On D-Day – Their Reaction Showed How Doomed Germany Was… June 7th,…

CH2 What Eisenhower Told His Staff When Patton Reached Bastogne First Gave Everyone A Chill

What Eisenhower Told His Staff When Patton Reached Bastogne First Gave Everyone A Chill In the bitter heart of…

CH2 When 64 Japanese Planes Attacked One P-40 — This Pilot’s Solution Left Everyone Speechless

When 64 Japanese Planes Attacked One P-40 — This Pilot’s Solution Left Everyone Speechless At 9:27 a.m. on December…

CH2 Why One Private Started Using “Wrong” Grenades — And Cleared 20 Japanese Bunkers in One Day

Why One Private Started Using “Wrong” Grenades — And Cleared 20 Japanese Bunkers in One Day May 18th, 1944,…

CH2 How One Metallurgist’s “FORBIDDEN” Alloy Made Iowa Battleship Armor Stop 2,700-Pound AP Shells

How One Metallurgist’s “FORBIDDEN” Alloy Made Iowa Battleship Armor Stop 2,700-Pound AP Shells November 14th, 1942, Philadelphia Navy Yard,…

My Parents Chose My Sister Over Me, Like Always – Until the Letter I Left Made Her Scream In Anger And Disbelief…

My Parents Chose My Sister Over Me, Like Always – Until the Letter I Left Made Her Scream In Anger…

End of content

No more pages to load