THE FORK-TAILED THUNDER: The Untold Rise, Fall, and Redemption of the P-38 Lightning — America’s Most Misunderstood Fighter of World War II

The morning sun of July 26, 1943, burned through the mist that clung to the jungles of New Guinea, turning the Maram Valley into a furnace of light and shadow. The air was thick with the hum of insects and the far-off rumble of engines—a low, steady growl that rolled across the mountains like distant thunder. Then, cutting through the haze, came flashes of silver. Twin booms, twin tails, and the gleam of sunlight off polished metal—America’s fork-tailed fighters, the Lockheed P-38 Lightnings, slicing through the sky with lethal grace.

Below, the jungle floor remained a world of tangled green and unseen danger, where every rustle might conceal an enemy patrol. But above the clouds, the fight was different—a realm ruled by speed, nerve, and steel. At the controls of one of those shining warbirds was Lieutenant Richard Ira Bong, a twenty-three-year-old farm boy from Poplar, Wisconsin, with a reputation for calm precision and a heart that beat for both country and a girl named Marjorie back home. His P-38, “Marge,” carried her name and her photograph painted lovingly beneath the cockpit—his good-luck charm in a sky where luck was often the only thing that separated life from oblivion.

Bong had been in the air since dawn. His squadron, part of the 49th Fighter Group, had been dispatched to intercept enemy aircraft reported over the valley. Through the headset, his radio crackled with static and clipped voices—men he trusted, men who had already seen too many not return. The warning came fast and sharp: “Bandits, twelve o’clock high.” Bong’s gloved hands tightened around the controls as his eyes scanned the horizon. Then he saw them—dark specks glinting against the sun. Japanese fighters, climbing fast.

Far ahead, sunlight flared on the wings of Nakajima Ki-43 Oscars and Kawasaki Ki-61 Tonys, the pride of Japan’s 68th Sentai. They were beautiful machines, light, agile, and deadly in the right hands. The men flying them were no amateurs—they were veterans of China and Burma, some with more kills than Bong himself. But the young American ace knew something they did not: the game had changed. The era of single-engine dogfights fought at close range was ending. The future belonged to planes that could climb faster, dive harder, and strike from beyond reach.

And that future had a name—the P-38 Lightning.

The sky erupted into chaos as the two formations met. Tracers carved glowing arcs through the air, and engines roared like furious beasts. Bong’s twin engines howled as he dove through the enemy formation, his six .50-caliber guns spitting fire. He squeezed the trigger, and one Oscar burst into flame, spinning down toward the jungle below. He pulled up hard, banking into the sunlight, and dove again. Another target crossed his sights—one burst, one kill. Then another. And another.

When it was over, the smoke trails told the story. Four enemy planes fell that morning, their black plumes twisting into the green below. Bong’s tally that day brought his total to fifteen. He was already halfway to becoming America’s top ace, though he didn’t think about records. He thought about Marge. He thought about the men who hadn’t made it back. And he thought about the strange, miraculous machine that had carried him through—his P-38, the fighter that was rewriting the rules of air combat.

Yet for all its glory, the P-38’s story was not one of easy triumph. Behind every victory lay years of struggle, skepticism, and misunderstanding. The Lightning would come to symbolize American ingenuity at its boldest—but its road to redemption began in the shadow of doubt.

The Lightning’s birth traced back to a time when America’s military was still flying relics of another age. In 1938, while Europe braced for war, the United States Army Air Corps issued a bold challenge to the nation’s aircraft manufacturers. The call came under the name Circular Proposal X-608, and its demands were audacious: design a high-speed, high-altitude interceptor capable of reaching at least 360 miles per hour, climbing to 20,000 feet in six minutes, and carrying over 1,000 pounds of armament. It was a request that bordered on the impossible.

Two men within the Air Corps believed the impossible was worth pursuing. Lieutenant Benjamin S. Kelsey and Lieutenant Gordon P. Saville, both visionary young officers, were convinced that the future of warfare would be decided in the skies—and that America needed fighters faster, stronger, and deadlier than anything the world had ever seen. They imagined a machine that could hunt bombers at 30,000 feet, outrun anything it couldn’t outfight, and outgun anything it couldn’t outrun. But they also knew the roadblocks ahead. The Army’s bureaucratic restrictions limited pursuit aircraft to no more than 500 pounds of armament—barely enough to make a dent in an enemy bomber.

Kelsey and Saville decided to outsmart their own system. They rewrote the specifications, classifying the new aircraft not as a “pursuit” plane but as an “interceptor.” With one stroke of the pen, the limits vanished. The Air Corps would now accept a fighter that carried twice the firepower and pushed the limits of engineering to their breaking point.

When the proposal reached Lockheed Aircraft Company in Burbank, California, it landed in the hands of a young aeronautical genius named Clarence “Kelly” Johnson. At just twenty-eight, Johnson was already known as the company’s maverick—brilliant, stubborn, and unafraid of risk. He gathered a small team and began sketching ideas that looked like they belonged to another century. Where other companies designed single-engine planes with sleek noses and traditional tails, Johnson’s concept was something no one had ever seen: two engines mounted on twin booms, joined by a central pod that housed the pilot and all the guns.

The design looked strange, even alien. Critics called it impractical. Some engineers laughed outright. But Johnson and his team believed the configuration could solve multiple problems at once—redundancy, power, and speed. Two engines meant safety if one failed. The central nacelle eliminated the need for synchronized guns firing through a propeller, allowing all weapons to be concentrated in a single devastating burst. And with turbo-superchargers feeding its twin Allison V-1710 engines, it could climb higher and faster than anything else in the sky.

In early 1939, Lockheed rolled out the first prototype—the XP-38. It gleamed like a blade under the California sun, its twin tails giving it a predator’s stance even while standing still. On January 27, Lieutenant Kelsey himself climbed into the cockpit for the maiden flight. The takeoff was smooth, the engines steady, and as the plane climbed, it shattered expectations. The P-38 reached 420 miles per hour in testing—faster than any American aircraft ever built.

To prove its potential, Kelsey decided to push the machine even further. He set out to break the transcontinental speed record, flying from California to New York. For seven hours, the Lightning roared across the country, averaging speeds unheard of for a piston-engine plane. Reporters waited at Mitchel Field to witness aviation history. But as the plane descended, disaster struck. Ice formed on the carburetors, choking the engines. The XP-38 lost power and crashed short of the runway, breaking apart in a tangle of metal and smoke.

Miraculously, Kelsey survived. He crawled from the wreckage bruised but alive, his uniform streaked with oil. The prototype was gone, but its legend was just beginning. In that brief flight, the Lightning had done enough to prove itself. It had shown that American engineering could produce something that matched, even surpassed, the best designs of Europe. That’s just the start of the saga…

Continue below

The morning sun of July 26, 1943, blazed hot over the jungles of New Guinea, cutting through the heavy mist that lingered above the Maram Valley. The air shimmered with the heat, and above that vast emerald wilderness, silver flashes darted through the sky—twin-engine warbirds streaking low over the jungle canopy. They were P-38 Lightnings of the United States Army Air Forces, roaring eastward in search of their prey.

Below them, the jungle floor was alive with unseen danger. But above the clouds, these men had found their own kind of battleground—a place of speed, precision, and death. At the controls of one of those twin-boom fighters was Lieutenant Richard Ira Bong, a twenty-three-year-old from Poplar, Wisconsin. In the cockpit of his beloved aircraft “Marge,” named after his sweetheart back home, Bong’s eyes scanned the skies. Moments later, his radio crackled—the enemy had been sighted.

Far ahead, sunlight glinted off the wings of incoming Japanese fighters—Nakajima Ki-43 Oscars and Kawasaki Ki-61 Tonys—the pride of Japan’s 68th Sentai. They were nimble, lethal, and flown by some of Japan’s most battle-hardened aces. But today, they would meet the machine that would change the course of the Pacific air war—the Lockheed P-38 Lightning.

As the two forces clashed over the valley, the air became chaos. Engines screamed, tracers arced across the sky, and explosions echoed through the clouds. Bong’s guns roared as his Lightning sliced through the formation. One enemy aircraft burst into flames. Then another. By the time the dogfight ended, four Japanese fighters were falling in smoke and ruin toward the jungle below. Bong’s score that day—four confirmed kills—brought his tally to fifteen. He was already halfway to becoming America’s greatest ace.

But Bong’s triumph was only the surface of a far more complicated story—a story of ambition, innovation, tragedy, and redemption. The P-38 Lightning, now remembered as one of the most iconic fighters of World War II, was once regarded as a failure—a misunderstood machine whose brilliance was nearly buried by confusion and controversy.

The Lightning’s story began not in the Pacific skies but in the corridors of power in Washington, D.C., and the design rooms of California’s Lockheed Aircraft Company. The year was 1938, and the United States Army Air Corps was seeking something revolutionary. The Air Corps issued a bold request under the designation Circular Proposal X-608—a call for a high-altitude, high-speed interceptor capable of reaching 360 miles per hour at altitude, climbing to 20,000 feet in six minutes, and carrying more than 1,000 pounds of armament.

The proposal came from two forward-thinking officers: Lieutenant Benjamin S. Kelsey and Lieutenant Gordon P. Saville. Both men were visionaries—pilots who saw that the future of aerial combat would belong not to the slow, maneuverable biplanes of the past, but to powerful, fast, and heavily armed machines that could strike with precision and vanish before the enemy could respond.

But there was a problem. The Army’s regulations limited fighter—or “pursuit”—aircraft to 500 pounds of armament. Kelsey and Saville refused to accept that constraint. They sidestepped the rule by designating their new concept as an “interceptor,” not a pursuit plane, allowing them to double the firepower requirement.

Lockheed engineers, led by the brilliant Clarence “Kelly” Johnson, responded with a design that looked like nothing else in the sky—a twin-boom fuselage with the pilot and guns mounted in a central nacelle. It would be powered by two liquid-cooled Allison V-1710 engines with turbo-superchargers, giving it unmatched speed and range. To the military’s amazement, the prototype exceeded every expectation.

On January 27, 1939, the first prototype, designated XP-38, took to the air with Lieutenant Kelsey himself at the controls. It reached 420 miles per hour in testing—faster than any American aircraft ever built. Kelsey even set a transcontinental speed record, flying from California to New York in just seven hours and two minutes. But as he approached Mitchel Field, his engines began to ice over. The XP-38 crash-landed short of the runway, shattering into pieces. Kelsey survived, bruised but alive—and so did the reputation of his plane. The demonstration had been enough. The Army ordered the design into production.

Lockheed’s sleek, radical machine was christened the P-38 “Atlanta”—a name later changed by the British Royal Air Force to something more fitting: the “Lightning.”

By late 1941, the first operational P-38s rolled off the assembly line at Lockheed’s Burbank plant. The aircraft’s futuristic design drew attention wherever it appeared. With its long, narrow wings and twin tails, it looked unlike anything in the world’s skies. The press speculated endlessly about its performance. “A secret American interceptor,” wrote The New York Times in November 1941, “so powerful that observers cannot even locate its guns.”

But the Lightning’s early days were far from glorious. When Britain’s Royal Air Force received its first shipment of P-38s in 1942, they quickly encountered problems. The RAF had requested a version with both propellers turning in the same direction, rather than counter-rotating—a fatal decision. The modification made the aircraft dangerously unstable. Worse still, a phenomenon known as compressibility emerged during high-speed dives.

At extreme velocities, the Lightning’s controls would lock up, trapping pilots in dives they could not pull out of. Several test pilots were killed before Lockheed engineers—working day and night under Johnson’s direction—devised a solution: quick-acting dive flaps that restored control during steep descents. It worked, but the RAF had already lost faith. They canceled their orders, calling the P-38 “too dangerous to fly.”

Then came Pearl Harbor, and everything changed. The United States was at war, and every available aircraft—flawed or not—was pressed into service. The Army Air Forces ordered hundreds of Lightnings, and soon the first squadrons were deployed to the Aleutian Islands in Alaska, where the long-range fighter proved its worth.

On August 9, 1942, pilots of the 343rd Fighter Group intercepted two massive Japanese H6K “Mavis” flying boats. Both were shot down. The P-38 Lightning had scored its first combat kills.

Days later, in the Atlantic, another Lightning downed a German Fw 200 Condor—the first Luftwaffe aircraft destroyed by the U.S. Army Air Forces. The twin-boom fighter had now drawn blood in both theaters of war.

From the frozen coasts of Alaska to the deserts of North Africa, P-38 squadrons began to appear wherever American forces fought. Its heavy armament—four .50-caliber Browning machine guns and a 20mm cannon—all mounted in the nose—gave it unparalleled accuracy. Unlike other fighters that relied on wing-mounted guns, which required complex convergence angles, the Lightning’s weapons fired straight ahead. A skilled pilot could shred an enemy aircraft from hundreds of yards away.

But the Lightning’s climb to glory would not be smooth. When deployed to North Africa in late 1942, it faced the Luftwaffe head-on. German pilots flying Messerschmitt Bf-109s and Focke-Wulf 190s quickly learned the Lightning’s weaknesses. They dove away into high-speed escapes, knowing that the P-38’s compressibility issues prevented it from following. Losses mounted, and soon the P-38’s reputation plummeted.

American newspapers began referring to it as “the jinxed fighter.” Life Magazine published an article calling it “the most hoodooed aircraft in American service.” To repair its image, the Army Air Forces circulated a morale-boosting story: a captured German pilot, trembling in fear, had supposedly called it “Der Gabelschwanz Teufel”—the Fork-Tailed Devil. The tale became legend, though no such German phrase was ever verified.

Behind the propaganda, the reality was grim. Pilots struggled with freezing cockpits in the cold European climate, their breath crystallizing on the glass as their unheated cabins turned to iceboxes. Rumors spread that the P-38 was impossible to bail out of due to its twin booms. Lockheed was forced to produce training films assuring pilots that escape was possible—if done correctly.

And yet, through the adversity, the Lightning’s defenders refused to give up. Among them was the ever-brilliant Benjamin Kelsey, who had secretly ensured that Lockheed’s design could carry drop tanks, doubling its range. He had done this against official policy—at a time when Air Corps leadership, dominated by “bomber generals,” refused to prioritize fighters at all. His foresight saved the P-38. When American bombers began their daylight offensive against Germany, the Lightning was the only Allied fighter with the range to escort them deep into enemy territory.

By 1943, the P-38 Lightning stood at a crossroads—its reputation battered, its capabilities doubted, yet its potential undeniable. In the Pacific, however, a new chapter was beginning—one that would transform this misunderstood machine into a legend.

Thousands of miles from the European front, in the vast reaches of the South Pacific, the Lightning was about to find its true home—and in the hands of daring young pilots like Richard Bong, it would become not just a weapon of war, but a symbol of American ingenuity, audacity, and redemption.

By the winter of 1942, the Mediterranean skies had turned into a proving ground for the P-38 Lightning. The U.S. Army Air Forces had thrown the aircraft into its first large-scale air campaign over North Africa. Dust swirled around makeshift runways in Tunisia as mechanics toiled in the heat, tightening bolts and checking engines that often overheated under the desert sun. The pilots—some barely out of flight school—looked at the sleek, twin-tailed machines and wondered if this strange new design could truly survive in combat.

The enemy waiting for them was the Luftwaffe, experienced and ruthless. German pilots like Adolf Galland, Hans Bär, and Franz Stigler had been fighting since 1939. They knew every trick in the book. Against such veterans, the Americans were rookies—green, confident, but untested.

The P-38 entered the fight with the 12th Air Force in late 1942. On paper, it was formidable: a top speed of 400 mph, a climb rate unmatched by any other American fighter, and a devastating nose-mounted armament that could tear through enemy bombers and fighters alike. But reality quickly proved harsher than anyone had expected.

In the skies over Tunisia and Sicily, the P-38’s first large engagements with German aircraft revealed both its strengths and its fatal weaknesses. The Lightning could dive faster than almost any Allied fighter, but if pushed too far, it entered compressibility—the aerodynamic demon that froze the controls solid. Pilots who tried to pull out at high speed often couldn’t. Some blacked out; others never woke again.

The Luftwaffe learned quickly. Whenever a Lightning gained an advantage, German pilots would simply roll inverted and dive away. The Americans couldn’t follow. To the Germans, it became almost a sport.

Losses mounted. The men in the 82nd and 1st Fighter Groups—both early P-38 units—watched friends disappear into the clouds, never to return. Many of those who survived blamed themselves; others blamed the aircraft. “She’s fast,” one pilot wrote in his diary, “but she’ll kill you quicker than the enemy if you don’t respect her.”

Despite the setbacks, moments of brilliance began to emerge. In April 1943, the 82nd Fighter Group achieved a stunning victory over Tunisia, claiming thirty-one German aircraft destroyed in a single day. Life Magazine picked up the story, running an article that declared, “The Fork-Tailed Fighter Lives Down Its Hoodoo to Sweep Enemy Skies.”

The story included a dramatic, likely fabricated quote from a captured German pilot, who supposedly called the Lightning “Der Gabelschwanz Teufel”—the Fork-Tailed Devil. The phrase stuck, and from then on, the P-38’s image began to shift. For the first time, it wasn’t seen as cursed—it was feared.

But propaganda couldn’t hide the real difficulties. Pilots in the Mediterranean faced the same challenges their comrades in England later would. The twin-boom design placed the cockpit far from the engines, leaving pilots freezing at altitude in winter and baking in summer. With no engine in front to warm the cockpit, the canopy often frosted over, turning visibility into a nightmare. Some pilots resorted to carrying hot-water bottles or wrapping their boots in rags.

There were other problems, too. In combat, the Lightning’s engines sometimes failed at high altitudes due to supercharger malfunctions. The aircraft’s size made it an easy target; its distinctive silhouette—two tails, one central pod—stood out against the blue sky, even from miles away. And while the P-38 could outclimb and outshoot most Axis aircraft, it couldn’t outturn them. Against agile Messerschmitt Bf 109s or Focke-Wulf 190s, it was often outmaneuvered.

Still, American engineers and pilots refused to give up. Lockheed’s test division worked tirelessly on improvements. Dive-recovery flaps were fitted beneath the wings, allowing the aircraft to safely pull out of compressibility dives. New engines with improved turbo-superchargers reduced failures. And a young Lockheed test pilot, Tony LeVier, became the Lightning’s most passionate advocate.

LeVier flew demonstration tours across Allied bases in 1944, performing wild maneuvers that most combat pilots had been warned never to attempt. Rolls, dives, vertical climbs—he showed that, in the right hands, the Lightning was not just safe, but extraordinary. His demonstrations convinced many skeptics that the P-38’s potential had not yet been fully realized.

But the tide of air warfare was changing. In the European theater, two new American fighters—the P-47 Thunderbolt and the P-51 Mustang—were entering service. Both were faster, simpler, and easier to maintain. The Mustang, in particular, with its Rolls-Royce Merlin engine, could outfly almost anything in the air. Gradually, the P-38 was relegated to secondary roles: long-range escort, reconnaissance, and ground attack.

Yet even as Europe began to turn its back on the Lightning, another theater embraced it completely.

In the Pacific, where the distances were vast, the jungles endless, and the ocean merciless, the P-38 was not a liability—it was a savior. Its twin engines gave it the range and reliability no single-engine aircraft could match. Its heavy armament made it perfect for destroying lightly built Japanese planes. And its long legs allowed it to escort bombers on missions no other fighter could reach.

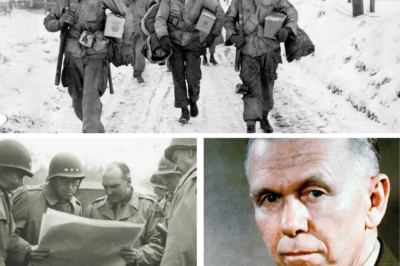

General George C. Kenney, commander of the Fifth Air Force in the Southwest Pacific, recognized this immediately. While his peers in Europe debated the Lightning’s flaws, Kenney saw only its potential. “I’ll take all the P-38s you can give me,” he told Washington bluntly.

He got them.

By early 1943, the skies over New Guinea had become the proving ground for America’s twin-tailed beast. The Lightning’s arrival transformed the air war. Where once Japanese Zeros and Oscars had ruled the skies, they now faced an enemy that could climb higher, strike harder, and fly twice as far.

The difference was almost unfair. The Japanese fighters were nimble but fragile, their airframes built for lightness, not endurance. A few bursts from the P-38’s concentrated guns tore them apart. “The Lightning’s punch was like being hit with a sledgehammer,” one Japanese pilot later admitted.

In the Pacific, the Lightning’s flaws became virtues. Its large frame, once a liability, now meant survivability. Pilots often returned to base with one engine destroyed or half the tail shot off. Its cool-running twin Allisons were perfect for the tropical heat. And its unheated cockpit, miserable in Europe, was a blessing in the sweltering jungles of New Guinea.

Above all, the P-38 offered something no other fighter could—range.

That range would soon make history.

In early 1943, American intelligence cracked a message that would change the course of the war. It revealed that Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, the mastermind of Pearl Harbor, was planning an inspection tour of Japanese bases in the Solomon Islands. His route, time, and aircraft were all listed.

The mission to intercept him fell to Major John W. Mitchell and a squadron of P-38 Lightnings from the 339th Fighter Squadron, 347th Fighter Group. The problem? Yamamoto’s flight would take place more than 400 miles from the nearest Allied base—well beyond the reach of any other Allied fighter. The P-38 was the only aircraft in the Pacific that could make the trip.

On the morning of April 18, 1943, eighteen P-38s lifted off from Guadalcanal. Flying at wave-top height to avoid radar detection, they raced across the ocean in perfect formation. After nearly two hours, their navigation—calculated to the minute—brought them directly to their target.

There, in the morning sunlight, two Japanese bombers escorted by six Zeros appeared over the island of Bougainville. The Americans climbed silently, unseen. Then they struck.

In the span of minutes, chaos erupted in the sky. Lieutenant Rex T. Barber and Captain Thomas G. Lanphier dove on the lead bomber. Cannon shells ripped through its fuselage, and the aircraft burst into flames. It crashed into the jungle below. Inside that shattered bomber was Admiral Yamamoto himself.

The mission, conducted entirely by P-38s, was a masterpiece of precision and audacity. It became one of the most celebrated air operations of the war—a strike that stunned Japan and electrified America.

Back home, headlines screamed: “YAMAMOTO DOWNED BY LIGHTNING STRIKE!”

The P-38 Lightning was no longer the “hoodooed” fighter of the Mediterranean. It was now the avenger of Pearl Harbor—the aircraft that had slain Japan’s greatest strategist.

In the months that followed, the Lightning’s legend grew. Pilots like Richard Bong, Thomas McGuire, Charles MacDonald, and Jay Robbins used it to carve their names into history. In the Pacific, where the distances were immense and the battles relentless, the P-38 was king.

It was fast. It was deadly. And at last—it was respected.

But the saga of the Lightning was far from over. For even as it triumphed in the Pacific, engineers and commanders still fought to refine it, to make it the perfect weapon it had always promised to be. The aircraft’s reputation had been saved—but its story, full of danger, rivalry, and sacrifice, was still unfolding in skies from New Guinea to the Philippines.

The air above the Pacific had its own kind of silence. Not the stillness of peace, but the heavy, endless hum of engines echoing across open water. By 1944, those sounds belonged to the P-38 Lightning—a machine that had transformed from a misunderstood prototype into the very spearhead of America’s air war in the Pacific.

General George C. Kenney, commanding the Fifth Air Force from his headquarters in New Guinea, had made the Lightning his weapon of choice. While the jungles below hid Japanese supply lines, Kenney’s twin-tailed fighters ranged hundreds of miles in every direction, hitting enemy airfields, bombers, and ships with surgical precision. In an era when distance and endurance could decide a battle, the P-38 was unmatched.

The pilots who flew them were young—many barely out of high school—but their courage and skill turned the Lightning into a legend. Among them was Major Richard Ira Bong, a quiet, smiling Wisconsin farm boy whose lethal precision would make him America’s deadliest ace.

By the summer of 1943, Bong had become a symbol of everything the P-38 represented—speed, daring, and resilience. His aircraft, marked with a hand-painted portrait of his sweetheart Marge Vattendahl, became as famous as he was. “Marge” wasn’t just a plane; she was a good-luck charm, a companion, and a piece of home carried through the war-torn skies of the Pacific.

Bong’s squadron—the 9th Fighter Squadron, 49th Fighter Group—operated from rough, muddy airstrips carved out of the jungle. The air was thick with humidity and the smell of aviation fuel. Pilots flew missions that stretched the limits of endurance—sometimes six or seven hours in the cockpit, fighting both the enemy and exhaustion.

The Lightning’s dual engines were both a blessing and a curse. They gave the aircraft range and redundancy, allowing pilots to limp home even with one propeller dead. But they also required constant maintenance. Ground crews became magicians—working through the night under dim lanterns, covered in oil and sweat, to keep the birds flying.

The P-38’s cockpit was hot, stifling, and often smelled of gunpowder and ozone after every burst of fire. The control yoke trembled under power, and the twin Allison V-1710s behind the pilot’s shoulders drummed like thunder. When the guns spoke, their vibration shook the entire frame. Pilots later said they could feel their bullets rip through the sky before they even saw the tracers hit.

The Japanese, who had once ruled the air with the agile Mitsubishi A6M Zero, now faced a machine they couldn’t outclimb or outgun. The Lightning could attack from above, dive fast, and unleash five streams of death from its nose-mounted guns without the convergence problems that plagued most fighters. “The P-38 hits hard,” said one Japanese pilot captured after the war. “When it fires, it is like a giant hammer breaking glass.”

By late 1943, Bong’s legend was already spreading. On December 27, 1942, he had scored his first confirmed kill. By mid-1943, his tally reached fifteen. In January 1944, it climbed past twenty-five. Newspapers back home began printing his photo on the front page, calling him “America’s Ace of Aces.”

But Bong was not alone. Alongside him flew men who would carve out their own immortality in the P-38—Thomas McGuire, Charles H. MacDonald, Jay T. Robbins, and Gerald Johnson, to name a few. Each became a hero in his own right, and each shared the same fierce devotion to the twin-engine fighter that had carried them through countless battles.

It was during this time that the P-38 achieved one of its most legendary missions: Operation Vengeance—the interception and killing of Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, architect of the Pearl Harbor attack.

In April 1943, American intelligence intercepted a coded Japanese transmission revealing Yamamoto’s travel itinerary. His inspection flight would take him from Rabaul to the island of Bougainville—a 1,000-mile round trip through enemy-held territory. No Allied fighter except the P-38 could make the journey.

Major John W. Mitchell and his squadron of P-38s took off from Guadalcanal before dawn on April 18, flying low—barely fifty feet above the waves—to avoid radar detection. After flying for over two hours, guided by a single, precise navigation calculation, they arrived exactly where they expected: over Bougainville at 9:34 a.m.

Two Japanese bombers and six Zero escorts appeared ahead. Mitchell’s formation climbed silently, then pounced. The first bomber—Yamamoto’s—was shredded by cannon fire from Lieutenant Rex T. Barber’s Lightning. It plunged into the jungle, exploding in a ball of fire. The second bomber was destroyed moments later.

The entire mission had lasted less than ten minutes. But its impact was enormous. Yamamoto’s death shocked Japan and electrified America. For the first time, the P-38 was celebrated not just as a weapon but as an instrument of justice.

Back in the United States, Time magazine ran a full-page photo of the Lightning with the caption: “The Plane That Avenge Pearl Harbor.” It was the kind of victory the aircraft desperately needed.

As the Pacific campaign expanded, the P-38 became the backbone of long-range fighter operations. It escorted bombers to Rabaul, Wewak, Biak, and later to the Philippines. Its dual engines gave pilots confidence over open ocean—where a single-engine failure could mean a slow death in shark-infested waters.

In 1944, General Douglas MacArthur’s island-hopping strategy depended heavily on the P-38. Each time the Army established a new airfield on captured territory, Lightnings were among the first to land. They cleared the skies, strafed airfields, and escorted bombers deeper into Japanese territory.

The Lightning’s versatility was unmatched. It could dive-bomb ships, strafe convoys, or act as a photo-reconnaissance platform. The F-4 and F-5 recon variants, stripped of guns and equipped with cameras, provided invaluable intelligence before major invasions. Their pilots, often flying alone over enemy territory, risked everything to bring back images that would guide Allied strategy.

Back at Lockheed’s plant in Burbank, production surged. Factory workers—many of them women—assembled Lightnings around the clock. They painted names, hearts, and messages onto their creations before the planes were shipped to the front. To them, each Lightning was personal. “We build them,” one factory worker said, “and they come back as heroes.”

By mid-1944, the Lightning was reaching its peak. The improved P-38J model, with enhanced cooling, dive flaps, and a redesigned canopy, eliminated many of the early flaws. It could now outclimb almost anything in the Pacific theater and withstand the brutal conditions of tropical warfare.

And in those skies, Richard Bong was rewriting history.

Mission after mission, Bong’s kills mounted. He flew with quiet determination, often returning from sorties with calm understatement—“Got a few,” he would tell his crew chief. But his records told the truth. By mid-1944, he had surpassed Eddie Rickenbacker’s World War I record. By the end of the year, his total reached forty.

The Army Air Forces pulled him from combat shortly after, fearing that America’s most celebrated pilot would not survive another mission. Instead, Bong was sent home—a living legend. He married his sweetheart, Marge, and was celebrated in parades and war bond tours. His aircraft, “Marge,” became one of the most photographed planes of the war.

Meanwhile, in the Pacific, the Lightning’s dominance continued. Pilots like Major Thomas McGuire, a friend and rival of Bong, pushed the aircraft to its limits. McGuire, aggressive and fearless, became the second-highest-scoring American ace with thirty-eight kills—all in the P-38. Tragically, he would not live to see the war’s end, dying in combat over the Philippines in January 1945.

Despite such losses, the Lightning’s record was unmatched. By the end of World War II, P-38s had destroyed over 1,800 Japanese aircraft—more than any other Allied fighter in the Pacific. It was the only American fighter in production for the entire duration of the war, from Pearl Harbor to V-J Day.

The very design that had once been called “too strange to succeed” had become the weapon that won the skies.

In the closing months of the war, Lightnings were among the first aircraft to fly over Tokyo Bay as Japan prepared to surrender. Their long, slender wings glistened in the sunlight as they escorted American bombers on the final missions of the conflict. To the men who had flown them through fire and storm, the sight was bittersweet.

The P-38 Lightning had proven itself beyond all doubt. It had started as an experiment—dismissed by the British, doubted by the Americans, mocked by its enemies. Yet it had outlived them all.

It had crossed oceans no fighter had ever crossed. It had killed the man who planned Pearl Harbor. It had carried America’s greatest ace to glory.

But the world was changing. The jet age was dawning, and the roar of propellers would soon give way to the scream of turbines. The P-38, once the fastest thing in the sky, was about to be left behind.

Still, in those final days of 1945, as P-38s lined the airfields of the Pacific under the golden sunset of victory, they stood as symbols of what American ingenuity could achieve.

The summer of 1945 brought with it a strange mixture of triumph and exhaustion. Across the Pacific, the war’s end could be felt in the air—a slowing rhythm beneath the roar of engines, a sense that the storm which had consumed the world was finally breaking. Yet for the pilots of the P-38 Lightning, the missions continued. The Japanese still fought ferociously in the Philippines, on Okinawa, and across the vast waters that separated the dying empire from its final stand. The Lightning, that sleek twin-boomed predator once dismissed as a curiosity, was now the battle-worn veteran of every front.

In those last months, the aircraft had evolved into something nearly perfect. The P-38L, the final combat model, carried everything its creators had ever dreamed of: dive flaps to tame its plunges, turbo-superchargers that gave it breath at altitude, and drop tanks that could stretch its range beyond two thousand miles. It was the ultimate incarnation of Clarence “Kelly” Johnson’s radical vision from seven years earlier—a machine that had been mocked, misunderstood, and feared, yet had survived every trial of war.

At forward bases on Leyte, Clark Field, and Ie Shima, P-38s sat lined up in the tropical heat, their polished skins dulled by salt and dust. Mechanics with bare arms and oil-blackened hands worked beneath their bellies, coaxing every last hour of flight from engines long past their prime. Pilots leaned against the booms, smoking in silence, staring out toward the horizon that had defined their youth.

They had seen the Lightning through everything—its humiliations in North Africa, its redemption in the Pacific, and its transformation from experiment to legend. But now, they were watching the twilight of an era.

When the B-29s began to fly from the Marianas, the nature of air war changed forever. The massive bombers could reach Japan itself, far beyond the Lightning’s range. Yet before the long-range escorting Mustangs could arrive, it was the P-38 that guarded them, slicing through the skies at the edge of endurance.

From Saipan and Tinian, Lightnings escorted the Superfortresses as far as the home islands. Their pilots reported seeing Mount Fuji glowing red in the dawn light, a sight both beautiful and haunting. Japanese anti-aircraft fire reached for them from below, but the P-38s flew on, steady and proud. For many, these were the last missions they would ever fly in combat.

Back in the United States, Major Richard Bong, now a national hero, had been taken off the front lines for his own safety. He toured war bond rallies, smiled for cameras, and shook hands with generals and movie stars. Yet the quiet farm boy never seemed entirely at ease in the spotlight. He missed the cockpit—the vibration of the engines, the hiss of the headset, the endless sky that had become his second home.

Then came a cruel twist of fate. In August 1945, on the very day the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, Richard Bong climbed into a new aircraft—the Lockheed P-80 Shooting Star, America’s first operational jet fighter. He was testing it for the Army Air Forces at Burbank, California. Moments after takeoff, the jet’s fuel system malfunctioned. The aircraft caught fire. Bong tried to bail out, but his parachute failed to open in time. He was killed instantly, just thirty-four days before the end of the war he had helped to win.

The news hit the nation like a thunderclap. The “Ace of Aces,” America’s greatest fighter pilot, had died not in battle, but in the birth of the jet age. His death marked, in a tragic and poetic way, the end of the Lightning’s era.

That same week, thousands of miles away, other P-38s flew their last missions over Japan. They strafed airfields, attacked supply convoys, and photographed burning cities from the thin blue edge of the sky. Then, as the Emperor’s voice echoed across the radio waves announcing Japan’s surrender, the Lightnings turned homeward one final time.

The men who flew them would never forget what it felt like. The twin hum of the Allison engines behind the cockpit. The nose heavy with guns. The sensation of weightless power when the throttles were pushed forward. The Lightning had given them something no other aircraft could—a strange kind of immortality in the skies.

After the war, most P-38s were scrapped almost immediately. They were too complex, too expensive, and—suddenly—too slow. The world wanted jets, not propellers. Rows of gleaming Lightnings were parked in dusty airfields in the Philippines, Guam, and Hawaii, their engines silent, their aluminum bodies baking in the sun. Many were bulldozed into the ground, others stripped for parts. Some were simply left to rot beneath the tropical rain.

For the engineers who had built them, it was heartbreaking. Clarence “Kelly” Johnson, the genius behind the design, later wrote, “The P-38 was more than an airplane. It was a leap of faith. We built something that had never been seen before, and the world caught up to it.”

But in that leap, America had learned to dream bigger. Lockheed’s experience building the Lightning paved the way for everything that came after—the P-80 jet, the U-2 spy plane, even the SR-71 Blackbird. Every radical concept that Kelly Johnson’s team dared to try in the following decades began with lessons learned from the P-38.

And though the Lightning disappeared from the skies, it never vanished from the hearts of those who had flown her. Veterans spoke of the aircraft in reverent tones, as if remembering an old friend who had saved their life more than once. They remembered the way she sounded, the way she glided when one engine failed, the way she could rise like an arrow through the clouds.

Many said the P-38 was not just an airplane, but a companion—a faithful partner that had carried them through the worst of the war and brought them home again.

In the years that followed, the surviving Lightnings found new homes in unexpected places. Some were sold to foreign air forces—Portugal, Honduras, and Italy among them. Others became civilian photo-reconnaissance planes, flying long survey missions over the Arctic and the American West. One even made its way to Hollywood, where it appeared in newsreels and movies as the “star” of its own story.

In 1946, a few of the most famous P-38s—those flown by Bong, McGuire, and MacDonald—were preserved and displayed at airfields across the country. The rest faded into memory.

But for those who remembered the war, the image of the twin-tailed fighter streaking across the Pacific sky remained eternal. To them, it was the sound of victory—the gleaming shape that had cut through storm clouds and enemy fire alike.

Decades later, in airshows across America, the Lightning would return once more. Restored by private collectors and warbird enthusiasts, surviving P-38s took to the sky again, their engines singing the same deep note they had in 1943. Veterans would stand on the tarmac, their hands trembling, tears in their eyes as the familiar shape banked overhead.

It wasn’t just nostalgia—it was remembrance. Each gleaming P-38 that flew above the crowds was a monument not of metal, but of memory.

The Lightning’s legacy also lived on in the minds of engineers and pilots who came after. Its radical twin-boom design inspired generations of aircraft designers. Its lessons in high-speed aerodynamics shaped future jet fighters. Its victories in the Pacific became part of the mythology of the U.S. Air Force—the belief that technology, courage, and imagination could overcome even the most impossible odds.

And then there was the human legacy—the men who had built, flown, and fought with it. For them, the Lightning was a teacher. It punished carelessness and rewarded precision. It demanded respect, and those who gave it that respect were rewarded with survival—and, often, victory.

In time, historians would come to see the P-38 for what it truly was: the bridge between eras, the missing link between the fragile fabric-covered biplanes of the 1930s and the roaring jets of the modern age. It was the aircraft that proved America could innovate, mass-produce, and dominate in the air all at once.

It had been mocked by allies, doubted by commanders, and misunderstood by the public. But in the hands of brave pilots like Richard Bong, Thomas McGuire, Charles MacDonald, and countless others, it had become the lightning bolt that struck across the world’s darkest skies.

When Bong’s widow, Marge, visited his old P-38 after the war—a weathered, bullet-pocked relic stored at a museum hangar—she placed her hand gently on its metal skin. “This is the sound I remember,” she whispered as her fingers brushed against the cool aluminum. “The hum of the engines. The sound of him coming home.”

In that moment, the story of the Lightning came full circle.

Born from imagination, tested by fire, misunderstood, and redeemed by war, the P-38 Lightning became more than a machine. It was a symbol—of risk, of perseverance, of the belief that even the strangest ideas could soar.

And though the jet age would soon roar to life, the echo of those twin engines—the hum of lightning in the sky—would never fade.

The legend had begun in the imagination of a few daring engineers in 1938. It had grown through struggle, sacrifice, and brilliance. And when it ended, it left behind not wreckage, but a trail of light that still burns across history’s horizon.

Because in the end, the P-38 Lightning was never just about war—it was about what happens when courage meets innovation, and when a nation dares to dream faster than fear can catch it.

News

CH2 The Atlantic Wall: Why Did Hitler’s “Greatest Fortification” Fail? – Newly Unearthed WWII Secrets Revealed

The Atlantic Wall: Why Did Hitler’s “Greatest Fortification” Fail? – Newly Unearthed WWII Secrets Revealed By 1944, Europe had…

CH2 The Secret That Changed WAR FOREVER: How America’s “Counterattack Instinct” Rewrote the Rules of Battle and Crushed Hitler’s Armies While Other Allies Took Cover First

The Secret That Changed WAR FOREVER: How America’s “Counterattack Instinct” Rewrote the Rules of Battle and Crushed Hitler’s Armies While…

CH2 ‘You’ll Never Find Us!’ Japanese Captain Laughs in the Fog—But American Radar Sees All, Turning the Solomon Sea Into a Death Trap

‘You’ll Never Find Us!’ Japanese Captain Laughs in the Fog—But American Radar Sees All, Turning the Solomon Sea Into a…

CH2 How a Young Mathematician from Buffalo Cracked the Code That Changed the Course of World War II And Shorten It By 2 Years – The Effort Hinged on Her Discovery

How a Young Mathematician from Buffalo Cracked the Code That Changed the Course of World War II And Shorten It…

CH2 How a Petite 24-Year-Old Belgian Woman Defied Nazis, Braved the Pyrenees 24 Times, and Personally Saved 776 Allied Lives—The Shocking True Story They Tried to Erase

How a Petite 24-Year-Old Belgian Woman Defied Nazis, Braved the Pyrenees 24 Times, and Personally Saved 776 Allied Lives—The Shocking…

CH2 How One B17 Ball Turret Gunner’s Brutal Patience Annihilated a Luftwaffe Squadron in Minutes and Rewrote Aerial Combat Doctrine Forever

How One B17 Ball Turret Gunner’s Brutal Patience Annihilated a Luftwaffe Squadron in Minutes and Rewrote Aerial Combat Doctrine Forever…

End of content

No more pages to load