The Decision That Saved 100,000 Lives On One Of The Most Brutal Campaign in WW2 — The Miracle Happened in Rabaul

November 1st, 1943. 07:30 hours. A gray dawn rolled over the Solomon Sea as Lieutenant General Alexander Vandegrift stood on the bridge of the command ship Macaulay. The sky was low and heavy with mist, the kind that clung to the horizon like smoke from a dying fire. Through that haze, the coastline of Bougainville slowly revealed itself—dense jungle, dark ridges, and the faint white sliver of sand at Empress Augusta Bay. In less than two hours, fourteen thousand Marines of the Third Marine Division would hit those beaches, their landing craft churning the surf in perfect formation. It was another day in the Pacific War, but to Vandegrift, it felt different. This time, he wasn’t just leading an invasion. He was executing a gamble—one that went against everything the textbooks taught and everything his instincts told him as a combat Marine.

Two hundred and fifty miles to the northwest, the Japanese fortress of Rabaul sat like a coiled dragon at the edge of the Bismarck Sea. One hundred and ten thousand Japanese troops were stationed there—infantry, airmen, gunners, and engineers—an entire army waiting for the invasion they were certain would come. It was the stronghold that guarded the South Pacific, the anchor of Japan’s defensive perimeter, and the one place Allied planners had said must be taken if the war was ever to move north. Yet as Vandegrift gazed through his binoculars toward the coast, he knew those men at Rabaul would remain exactly where they were. He would not give them the battle they had spent two years preparing for.

Vandegrift was no stranger to the cost of direct assaults. He had commanded the First Marine Division during the hellish campaign at Guadalcanal—six months of attrition, disease, and exhaustion for a prize that was little more than a name on a map. He had buried too many men who never made it off that island. The campaign had taught him that in the Pacific, victory didn’t always come from the biggest guns or the boldest charges. It came from knowing when not to fight.

Now, as he watched the swells slap against the Macaulay’s steel hull, that lesson weighed heavily on his mind. The next great offensive—Operation Cartwheel—was already in motion, aimed squarely at isolating and neutralizing Rabaul, the crown jewel of Japan’s southern defenses. Yet even before the Marines hit the beaches at Bougainville, the calculations behind the operation had shifted. The cost of taking Rabaul directly was simply too high.

The bloody logic of island warfare was becoming impossible to ignore. Every victory in the Solomons had come at a staggering price. At Guadalcanal, seven thousand Allied troops had died to seize an airfield barely long enough for a bomber strip. The upcoming assault on Tarawa, only weeks away, would claim over three thousand American casualties for an island barely two miles across. And Rabaul? It was no tiny atoll or forgotten outpost. It was a fortress—massive, fortified, and alive with defenses on a scale no one had ever attempted to assault.

After seizing the town from a small Australian garrison in February 1942, the Japanese had transformed Rabaul into a bastion that dwarfed anything in the Pacific. The harbor, Simpson Harbor, could hold a hundred ships—battleships, carriers, transports, all sheltered beneath a ring of volcanoes. Five airfields surrounded it like a steel halo. The old Australian airstrips at Lakunai and Vunakanau had been expanded with thick concrete runways. Rapopo Airfield opened in December 1942 on the coast fourteen miles southeast of the town, while Tobera—later renamed Tero—was completed the following August. To the northwest lay Keravat, perched just thirteen miles from the coast. Together, they formed a network of air power that could launch or receive more than four hundred aircraft at once.

The defenses were staggering. Three hundred and sixty-seven anti-aircraft guns were positioned to create a near-impenetrable wall of fire around the harbor and airfields. Forty-three heavy coastal guns guarded every potential landing approach. Six thousand machine guns dotted the hills and ridges, each carefully positioned in reinforced bunkers and pillboxes designed to overlap in perfect fields of fire. Beneath the volcanic surface, Japanese engineers had carved a labyrinth of tunnels that stretched for hundreds of miles. These tunnels connected underground barracks capable of housing twenty thousand men, field hospitals for the wounded, armories packed with ammunition, and command centers buried so deep they were immune to all but the heaviest bombs.

By the middle of 1943, Rabaul was more than a military base—it was the nerve center of Japan’s South Pacific war effort. To the Allies, it was a target that had been burned into every map and briefing since Guadalcanal. Control Rabaul, and you controlled the Pacific. That had been the doctrine from the beginning. General Douglas MacArthur had called it the “key to the theater.” Admiral Ernest King had labeled it the “primary objective of 1943.” Operation Cartwheel itself—approved by the Combined Chiefs of Staff—was designed around one purpose: the encirclement and capture of Rabaul by March 1944.

Yet even before the operation began, cracks were forming in the plan. Intelligence analysts, studying aerial photographs and reports from coast watchers, began to realize what a direct assault on Rabaul would entail. The casualty estimates were horrifying. Every mile of coastline was fortified. Every approach was covered by pre-sighted artillery. Any landing force would face interlocking fire from guns concealed in jungle-covered ridges, machine guns firing from hidden embrasures, and mortar positions buried so deep that even days of bombardment couldn’t silence them.

If the Allies tried to take Rabaul head-on, they would be walking into a slaughter. The lessons of Guadalcanal had not been lost on the Japanese. They had watched, learned, and adapted. They knew how the Americans fought—how they used air power to soften defenses, how they relied on naval bombardment to clear the beaches, how their Marines needed space to form a beachhead. So they designed their defenses not to resist the first wave, but to destroy it. They built their tunnels to survive bombing, their artillery to withstand naval shelling, and their gun emplacements to eliminate landing craft the moment they touched sand.

The math was merciless. Intelligence officers predicted a thirty percent casualty rate in the first forty-eight hours of any invasion. That meant eighteen thousand dead and wounded—just to get ashore. And that was if everything went right. A single miscalculation in timing, weather, or coordination could turn Rabaul into a killing ground on a scale unseen since the Civil War.

Naval historian Samuel Eliot Morison would later write that “Tarawa, Iwo Jima, and Okinawa would pale beside the slaughter that would have occurred had the Allies tried to storm Rabaul.” Even those who hadn’t seen the classified projections could sense the truth. The fortress was impregnable, and every commander who studied the terrain came to the same grim conclusion: Rabaul could not be taken without destroying the very army sent to capture it.

The Japanese had turned the island into a trap—a perfect example of their new doctrine of defense through entrenchment. They had learned that they could not outproduce or outgun the Americans, but they could force them into battles of attrition where every yard of ground would cost blood. To take Rabaul, the Allies would have to strip resources from every other campaign—pull divisions from New Guinea, fleets from the Marshalls, bombers from China. It would mean gambling everything for a fortress that might not even fall.

And yet, for months, Rabaul remained the target. The idea of bypassing it seemed unthinkable. Every map, every war plan, every line of supply had been drawn with Rabaul at its center. It was the gateway to the Philippines, the choke point for Japan’s southern lifeline, the symbolic prize that promised victory in the Pacific. But slowly, quietly, a handful of voices began to question the logic of a direct assault.

Men like Admiral William Halsey, who had fought through the Solomon Islands, understood the price of frontal assaults. General George Kenney, commander of Allied Air Forces in the Southwest Pacific, argued that Rabaul could be neutralized, not conquered. They began to see a new kind of warfare emerging—a war not of head-on assaults, but of isolation, starvation, and bypass.

The numbers made it impossible to ignore. To capture Rabaul, it would take sixty thousand men, perhaps more. Of those, eighteen thousand would likely never return. The beaches were narrow, the approaches mined and sighted. The air defenses were so dense that a single bombing run could cost twenty aircraft. Even if the Allies succeeded in landing, they would face months of tunnel fighting, where every bunker was a fortress, and every ridge a deathtrap.

All this for an island that no longer needed to be taken. The Japanese could keep their fortress. The Americans would go around it.

That morning, as Vandegrift watched the mists thin over Empress Augusta Bay, he thought of the reports stacked on his desk below deck—the casualty estimates, the maps of gun emplacements, the intelligence photos showing miles of bunkers and anti-aircraft nests. Rabaul was waiting, but the war had changed. For the first time since Pearl Harbor, the Allies had the strength to choose where to fight—and where not to. There had to be a way.

Continue below

At 07:30 hours on November 1st, 1943, Lieutenant General Alexander Vandergrift stood on the bridge of the command ship Macaulay. Through the dissipating morning mist, he watched the coastline of Buganville emerge. In just 2 hours, 14,000 Marines from the Third Marine Division were scheduled to storm the beaches of Empress Augusta Bay.

The Japanese maintained a substantial force of 110,000 troops at Rabul, located 250 mi to the northwest. These troops were ostensibly positioned to prevent precisely what Vandergrift was about to execute. Yet, they would remain inactive. Vandergrift, a veteran commander of Marines at Guadal Canal, was acutely aware of the devastating consequences of attacking a fortified Japanese position. bloodshed.

The arduous island campaigns in the Solomons had resulted in thousands of casualties for objectives that were often barely discernible on a map. The upcoming battle at Terawa, just 3 weeks away, would tragically reaffirm this reality, costing over 3,000 casualties to seize a mere 2m long island. Rabol, however, was far from being 2 mi long.

It was a formidable fortress that dwarfed Tarawa into a training exercise. The Japanese had meticulously transformed Rabul into the most heavily defended position in the South Pacific. After capturing it from a small Australian garrison in February 1942, they dedicated 20 months to converting it into an unsinkable aircraft carrier.

Simpson Harbor possessed the capacity to anchor a 100 ships while five airfields encircled the harbor like a protective ring. Lacunai and Vuna pre-war Australian airirst strips were expanded with concrete runways. Rapopo opened in December 1942 on the coast 14 mi southeast of the town. Teru was completed in August 1943. Situated midway between Vuna Canau and Rapopo.

Keravat lay on the north coast 13 miles to the southwest. Collectively, these airfields boasted protective revetments for over 400 aircraft and runways capable of accommodating even the split tailed heaviest bombers in the Japanese arsenal. A staggering 367 anti-aircraft guns covered every conceivable approach to Simpson Harbor and its vital airfields.

An additional 43 coastal defense guns stood ready to repel any amphibious assault. Furthermore, 6,000 machine guns were strategically positioned in bunkers and pillboxes. The Japanese army had painstakingly carved hundreds of miles of tunnels into the volcanic rock, creating extensive underground barracks capable of housing 20,000 men, hospitals equipped to treat thousands of wounded ammunition dumps containing tens of thousands of tons of explosives, and command centers buried so deep that they were impervious to aerial bombardment. By mid 1943, over

110,000 Japanese soldiers, sailors, and airmen were stationed at Rabul, effectively transforming it into the Pearl Harbor of the South Pacific. The Allied plan had consistently centered on capturing Rabul. Every strategic document since Guadal Canal pointed toward this singular objective. Take Rabol and you control the South Pacific.

General Douglas MacArthur unequivocally called it the key to the theater. Admiral Ernest King identified it as the primary objective for 1943. The combined chiefs of staff formally approved Operation Cartwheel, specifically designed to encircle and capture Rabul by March 1944. However, military planners scrutinizing intelligence estimates identified a critical problem.

Seizing Rabal would result in more American lives lost than any battle since the Civil War. The Japanese had learned invaluable lessons from Guadal Canal and every subsequent island engagement in 1942. They fully anticipated that the Americans would arrive with naval gunfire and air superiority.

Knowing that Marines would establish beach heads, they constructed defenses specifically designed to transform these advantages into liabilities. The extensive tunnel network rendered strategic bombing largely ineffective. The dense concentration of anti-aircraft guns meant that providing air support would be a deadly undertaking. The sheer size of the garrison meant that achieving numerical superiority would necessitate stripping forces from every other theater.

Rabbal’s challenging geography offered only three potential landing beaches, all of which were narrow and covered by interlocking fields of fire emanating from positions that the Japanese had spent 18 months fortifying. Intelligence analysts predicted that an amphibious assault would result in a staggering 30% casualty rate. Naval historian Samuel Elliot Morrison would later reflect that Tarawa Ewoima and Okinawa would pale in comparison to the bloodbath that would have ensued had the allies attempted a direct assault on Fortress Rabul.

But in mid 1943, planners were already calculating that an assault force of 60,000 troops would suffer 18,000 killed and wounded. And that was assuming everything went according to plan. These grim estimates didn’t even factor in potential Japanese reinforcements from truck weather related delays or failed naval bombardments.

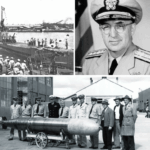

There had to be another way. The first American commander to perish attacking Rabul was Brigadier General Kenneth Walker. Walker commanded the fifth air force bomber command under General George Kenny. At 44 years old, he was a staunch theorist who firmly believed that strategic bombing could win wars without the need for ground invasions.

He had taught at the Airore Tactical School, authored doctrinal publications, and dedicated his entire career to arguing that air power, when properly applied, could obliterate any target. Rabul represented his chance to prove his theories. Walker flew his inaugural mission over Rabul in September 1942.

The raid proved largely inconsequential. Japanese fighters and intense anti-aircraft fire forced the bombers to retreat before they could inflict significant damage. However, Walker remained convinced that persistence would ultimately prevail. He believed in relentless attacks aiming to destroy enemy aircraft on the ground sink ships in the harbor and render runways unusable.

Eventually, he reasoned the base would become untenable. On January 5th, 1943, Walker personally led a daring daylight bombing raid on Simpson Harbor, employing six B17 Flying fortresses and six B-24 Liberators. The plan was to strike Japanese transports before they could depart for New Guinea.

General Kenny had initially ordered a dawn raid to minimize encounters with Japanese fighters, but Walker insisted on delaying the attack until noon, contending that his bombers required ample daylight to properly form up. 12 bombers launched an attack at high noon against the most heavily defended target in the Pacific. The Japanese were ready and waiting.

Fighters scrambled from three airfields to intercept the incoming bombers. Anti-aircraft guns unleashed a ferocious barrage from positions surrounding the entire harbor. Walker’s B17 Flying Fortress tail number 412 24458, nicknamed San Antonio Rose, sustained hits almost immediately.

Undeterred, he pressed the attack, leading the formation directly through the withering anti-aircraft fire. His bombardier successfully scored direct hits on Japanese vessels within the harbor. But then 15 Japanese fighters swarmed the formation. Walker’s bomber already damaged and trailing smoke was unable to maneuver effectively. Four or five zeros focused their attack on the lead aircraft.

Other crews watched in horror as the San Antonio Rose lost altitude heading towards the water with its number three engine smoking. The fighters relentlessly pursued it down into the clouds. Neither Walker, his crew of 10, nor the wreckage of his aircraft was ever recovered. Walker was postumously awarded the Medal of Honor. President Roosevelt presented it to Walker’s son on March 25th, 1943.

The citation lauded his conspicuous leadership and personal valor. However, it omitted the fact that the raid had failed to halt the Japanese convoy or that strategic bombing alone could not neutralize Rabul. Walker remains the highest ranking American officer still listed as missing in action from World War II.

The second major attempt came in October 1943. By this point, Allied forces had captured airfields close enough to mount sustained bombing campaigns. General Kenny meticulously planned a massive raid for October 12th involving an impressive 349 aircraft, the largest strike ever assembled in the Southwest Pacific.

The aerial armada included B-25 Mitchells, B24 Liberators, P38 Lightnings, and Australian Bowfort fighters. Essentially everything the Allies could put in the air. The raid simultaneously targeted all five airfields. Bombarders reported devastating results. Kenny’s afteraction report claimed over 100 Japanese aircraft destroyed on the ground, multiple fuel dumps set ablaze and runways rendered unusable. Theater command sent congratulatory messages.

MacArthur issued press releases declaring Rabul’s air power neutralized. However, the reality was far different. Japanese engineers swiftly repaired the runways within 36 hours. Most of the fuel dumps had been empty, the Japanese having moved the supplies underground weeks earlier. The aircraft count was wildly exaggerated. The Japanese had lost fewer than 20 planes, most of which were already damaged and awaiting parts.

The raid looked impressive in photographs, but Rabbal remained fully operational. Kenny tried again on November 2nd. 72 B-25 medium bombers and 80 P-38 fighters launched a daring low-level attack on Simpson Harbor, strafing and bombing at minimum altitude.

It was arguably the most perilous mission the fifth air force had undertaken. The Japanese had reinforced Rabol just one day earlier with 173 carrier aircraft manned by elite pilots drawn from the fleet carriers Zuikaku, Shokaku, and Zuho. Admiral Koga had stripped his combined fleet of its best aviators and dispatched them to defend Rabul.

These highly skilled pilots were lying in weight. The American Formation flew directly into what survivors would later describe as the toughest fight the Fifth Air Force encountered in the entire war. Japanese fighters met them at the harbor entrance. Anti-aircraft fire from ships and shore batteries created impenetrable walls of steel.

The B-25s pressed their attack, flying so low that their propellers kicked up spray from the harbor water. They scored hits on several ships and strafed aircraft revetments. However, nine B-25s did not return and 10 P-38s were shot down. Among the fallen was Major Raymond Herald Wilkins, commanding officer of the Eighth Bombardment Squadron, Third Bombardment Group.

Wilkins, 33 years old from San Bernardino, California, had flown 86 previous combat missions. On his 87th mission over Rabol, Wilkins courageously led his squadron into Simpson Harbor through intense anti-aircraft fire. His aircraft was hit multiple times, but he continued his bombing run, destroying a Japanese destroyer and a 9,000 ton transport.

His bomber trailing smoke and losing altitude could have turned for home. Instead, Wilkins made a strafing run on a heavy cruiser to draw fire away from his squadron. His aircraft was shot down and crashed into Simpson Harbor. All six crew members perished. Wilkins postuously received the Medal of Honor.

The November 2nd raid cost 19 aircraft and over 60 lives. In exchange, the Japanese lost only 20 aircraft and suffered minor damage to two cruisers. The raid had not neutralized Rabul. It had barely touched it. By mid November 1943, American commanders were faced with the stark reality of a year’s worth of raids that had yielded failureheavy losses and minimal results with a Japanese base that remained operational regardless of the frequency of attacks.

Strategic bombing had proven ineffective not due to a lack of courage on the part of the air crews, but because Rabol was simply too vast, too welldefended, and too easily repaired by the Japanese. The prospect of a ground campaign looked equally bleak.

American and Australian forces had been fighting up the New Guinea coast since January. Every mile gained came at a heavy price in casualties. The jungle terrain was worse than anything encountered in the Solomon’s dense rainforest, steep mountains, disease carrying mosquitoes and treacherous swamps. Malaria decimated entire battalions. Denge fever caused debilitating high temperatures. Dysentery weakened men until they were unable to walk.

Tropical ulcers infected even the smallest cuts and spread rapidly, causing flesh to rot. More soldiers were evacuated due to disease than from combat wounds. At Buuna and Gona on the northern Papuan coast, the campaign lasted from November 1942 through January 1943. Australian and American forces battled for three long months to clear two small coastal villages defended by a mere 6,500 Japanese troops.

The Allies committed 13,000 soldiers resulting in thousands of casualties. Over 7,000 Japanese were killed. The fighting was characterized by close quarters combat, brutal, and desperate engagements. Japanese bunkers constructed from coconut logs proved resistant to 30 caliber bullets, making flamethrowers the only effective weapon.

Men fought hand-to- hand in swamps and jungles. Unburied bodies lay rotting for weeks in the tropical heat, the pervasive smell of death permeating everything. When Buuna finally fell in January, American commanders realized they had stumbled into a new and particularly brutal kind of warfare. The Japanese would not retreat. They would not surrender.

Every position had to be taken through direct assault against defenders who fought to the death. If Buuna cost 3,000 casualties for just two villages, what would Rabul cost? At Nassau Bay on the New Guinea coast in late June 1943, American forces from the 41st Infantry Division landed to support Australian operations against Salamawa.

The landing was intended to be unopposed. Intelligence indicated that the beach was undefended. This intelligence proved to be fatally wrong. Japanese forces contested the landing. The Americans managed to get ashore, but spent weeks battling through dense jungle and swamps to link up with Australian units.

What planners had anticipated would take days ultimately took 6 weeks. Casualties mounted not from major battles, but from constant small unit actions, ambushes, snipers, and disease. At lay in early September 1943, MacArthur launched his most ambitious operation to date. The 503rd Parachute Infantry Regiment jumped onto Nadzub airfield while the Australian 9th Division landed amphibiously at Lei. The operation was flawlessly coordinated.

MacArthur himself flew over Nadzab to witness the paratroopers jump standing defiantly in the open doorway of a B7 bomber despite staff protests about the inherent danger. The landing was successful and the airfield was captured. Australian forces pushed inland but the Japanese 51st division defending Lei did not collapse. They conducted a fighting retreat through the jungle mountains toward Finch Hoffen.

The Australians pursued losing men to ambushes and exhaustion. Two weeks of operations cost the Australians 400 casualties. The Japanese lost over 2,000 killed, but many more escaped to fight elsewhere. Lei was captured, but the enemy army remained intact. This pattern repeated itself across New Guinea.

Finchen fell in October after fierce fighting. The Huan Peninsula was cleared by January 1944, but Japanese forces withdrew in good order. Every objective took longer and cost more than initially estimated. Every Japanese unit fought harder than predicted, and every victory simply moved the front line closer to Rabul, where 110,000 Japanese troops awaited in the strongest defensive position in the Pacific.

Allied planners scrutinizing these campaigns saw a clear mathematical equation that simply did not work. If taking a village cost 3,000 casualties and required 3 months, and if capturing an airfield cost 400 casualties and required 2 weeks, then assaulting Rabul with its five airfields massive garrison and extensive prepared defenses would result in casualties on a scale that the allies could not sustain. The numbers were inescapable.

The idea that ultimately changed everything did not originate from a single brilliant staff officer working late into the night. It evolved from years of strategic thinking that stretched back to 1921 when Major Earl Hancock Ellis of the Marine Corps authored War Plan 712, Advanced Base Operations in Micronia.

Ellis proposed that the United States could defeat Japan by capturing key islands while bypassing others, effectively strangling Japanese garrisons by controlling the sealanes. The concept was further refined by Admiral Raymond Rogers in War Plan Orange of 1911, but these remained theoretical plans for a hypothetical war. In June 1943, as Allied forces fought their way through the Solomon Islands toward Rabul, the Joint Strategic Survey Committee in Washington began to question whether capturing every Japanese base was strategically necessary. Their analysis concluded that

assaulting Rabul offered little promise of reasonable success given the fortress’s formidable strength. Committee members argued that if American forces could effectively control the sea and air around Rabul, the base itself would become strategically irrelevant.

The key advocate for bypassing Rabul was General George Catllet Marshall, the Army Chief of Staff. Marshall, 62 years old in 1943, was a strategic thinker who viewed the Pacific War primarily through the lens of logistics and casualty ratios rather than glory or conquest. He had spent the first two years of the war fighting for resources against British demands for European priority.

Every division sent to the Pacific was a division unavailable for the planned invasion of France. Every ship committed to island fighting was a ship not transporting vital supplies across the Atlantic. Marshall meticulously calculated resources the way an accountant calculates budgets.

He analyzed intelligence estimates for Rabal and ran the numbers. Assaulting the fortress would require a minimum of 60,000 assault troops and likely more like 75,000 when support units were factored in. These troops would have to be drawn from divisions earmarked for Europe or from units already stretched thin in the Pacific.

Casualties were projected to run between 30 and 40% in the first 2 weeks alone, which translated to 20,000 toward 30,000 killed and wounded. Replacing those losses would take months. Training their replacements would take even longer. Furthermore, even if the assault succeeded, Rabol itself offered no intrinsic value that justified the immense cost.

It was simply a base, not a strategic objective. Capturing it would accomplish nothing except denying it to Japan, which could be achieved far more effectively through isolation. Marshall presented this compelling analysis to the Joint Strategic Survey Committee in June 1943. The committee concurred. Their report concluded that assaulting Rabul held little promise of reasonable success and would seriously delay subsequent operations.

They recommended neutralization through air and naval power while focusing on advancing through positions that offered less resistance. However, a recommendation was not policy. The Joint Chiefs would have to approve it. and the joint chiefs included officers who strongly believed that major enemy positions must be captured, not bypassed. In the Pacific, General George Churchill, Kenny reached the same conclusion, albeit through different reasoning.

Kenny commanded the fifth air force under MacArthur. At 53 years old, he was an innovator who had pioneered skip bombing, low-level strafing attacks, and other tactical advancements. After witnessing his bombers batter Rabul for months with minimal impact, Kenny arrived at a fundamental realization.

You could not effectively destroy Rabool from the air because the base was simply too large and too dispersed. The Japanese had spread their facilities across hundreds of square miles. They had buried critical installations deep within tunnels. They repaired runways within hours. No amount of bombing would completely eliminate the base. However, Kenny also understood that you did not necessarily need to destroy Rabul.

You just needed to neutralize it. If Allied forces could establish airfields within fighter range of Rabul, those fighters could sweep over the Japanese base daily. Bombers could crater the runways faster than the Japanese could repair them. Fighters could shoot down any transport attempting to land.

Submarines and patrol bombers could sink any ship trying to enter Simpson Harbor. The garrison would be effectively trapped, unable to receive supplies, unable to launch aircraft, and unable to interfere with Allied operations, defeated without the need for a costly and bloody invasion. Kenny presented this concept to MacArthur in July 1943.

MacArthur’s initial response was negative. He had been planning to capture Rabbal since early 1942. His staff had invested months developing detailed invasion plans. His entire Southwest Pacific strategy hinged on Rabol as the culminating objective. Bypassing it felt like retreat, like leaving the job unfinished.

MacArthur told Kenny that the idea had merit, but expressed concerns about operational security, Japanese reinforcement capabilities, and potential negative press coverage for avoiding a fight. Kenny persisted. He presented MacArthur with projections of what the air campaign could achieve once the Bugganville airfields became operational. He described how submarines could effectively blockade Rabul.

He noted that the combined fleet was already withdrawing heavy ships from the base. He argued that time spent assaulting Rabul was time not spent advancing toward the Philippines and returning to the Philippines was MacArthur’s longheld obsession. That argument resonated deeply. By early August, MacArthur had shifted from outright opposition to reluctant acceptance.

He did not enthusiastically endorse bypassing Rabul. His messages to Washington still emphasized the importance of capturing the base. However, he stopped actively fighting the concept and allowed his staff to develop contingency plans for isolation rather than assault. Admiral William Frederick Hollyy Jr. arrived at the same conclusion through hard one battlefield experience.

Hollyy commanded the South Pacific area. He had been fighting through the Solomon Islands since assuming command in October 1942. He had witnessed Guadal Canal devolve into a six-month bloodbath. He had watched good men die on New Georgia, capturing airfields that could have been bypassed. He had lost ships, lost aircraft, and lost marines to diseases that ravaged jungle camps.

On August 15th, 1943, Holly implemented the first pure bypass operation of the Pacific War. Instead of assaulting the heavily fortified Japanese base on Colombangara in the central Solomons, he landed troops on the lightly defended Vela Lavella to the northwest. The operation was a resounding success.

American forces built an airfield on Vela Lavella while the Japanese garrison on Colombangara sat isolated and strategically irrelevant. 6 weeks later, the Japanese evacuated Colangara without American forces firing a single shot at the base itself. Holly had definitively proven that the bypass concept could work.

In August 1943, the combined chiefs of staff convened in Quebec for the Quadrant Conference. This gathering brought together American and British military leadership to coordinate strategy across all theaters of the war. The question of what to do about Rabbel dominated Pacific discussions.

Prime Minister Winston Churchill attended with his chiefs of staff. President Franklin Roosevelt brought Marshall King and General Henry Hap Arnold of the Army Air Forces. The conference lasted from August 17th through August 24th. Marshall presented the case for bypassing Rabul on August 19th. He had prepared meticulously.

He brought maps illustrating Rabol’s formidable defenses intelligence estimates of the garrison’s strength casualty projections for an amphibious assault and alternative plans for isolating the base. His presentation was methodical, logical, and devastatingly effective. He argued that assaulting Rabul would cost more American casualties than the Allied powers could afford, while achieving no strategic advantage that could not be gained through isolation.

The fortress controlled no essential territory. It threatened no vital installations. It posed a threat only if allowed to operate freely. Deny it that ability and it became strategically irrelevant. Admiral Ernest Joseph King, chief of naval operations, staunchly supported Marshall.

King, 64 years old, was known for being abrasive, difficult, and brilliant. He had been fighting for Pacific resources against European priorities since the attack on Pearl Harbor. He possessed precise knowledge of available ships, aircraft, and personnel. He was intimately familiar with the planned operations for the Central Pacific Drive through the Marshals and Marianas.

He told the combined chiefs bluntly that the Navy could not adequately support both the Rabul invasion and the Central Pacific offensive. One operation had to be sacrificed. The choice was stark spend resources, taking a fortress that offered no strategic gain, or spend those same resources advancing closer to Japan. King unequivocally voted for advancing toward Japan.

MacArthur’s representatives at Quebec continued to argue for capturing Rabul. Brigadier General Steven Chamberlain represented Southwest Pacific Area interests. Chamberlain was MacArthur’s operations officer, intelligent, loyal, and deeply committed to his commander’s vision. He argued that bypassing Rabol would leave a dangerous threat in the Allied rear areas.

He predicted that the Japanese would use Rabol to raid American supply lines. He warned that failing to capture such an important base would be perceived as a sign of weakness damage American credibility and embolden Japanese resistance elsewhere. Marshall countered every argument with casualty figures.

He directly asked Chamberlain, “How many marines is Rabbal worth 20,000 $40,000? At what point does the cost exceed the value?” Chamberlain had no answer. The question was unanswerable because Rabol held no strategic value that justified any casualties at all. It was merely a base and bases could be isolated. Marshall pressed his advantage.

The British chiefs of staff sided with Marshall. They were engaged in fighting in Burma, facing their own resource limitations and watching casualties mount in Italy. They had no interest in seeing American resources consumed in a battle that achieved nothing except denying Japan a base that could be denied through isolation.

Field Marshal Alan Brookke, chief of the Imperial General Staff, noted acidly that the Americans seemed adept at losing men taking islands, but less adept at advancing toward strategic objectives. It was far better to bypass the fortress and keep moving forward. On August 24th, 1943, the combined chiefs issued their directive. Rabul would be neutralized through air and naval action, but not captured.

Allied forces would seize positions on Buganville, the Green Islands, and the Admiral Ty Islands to establish airfields within range. These airfields would maintain constant pressure on Rabul, prevent reinforcement interdict supply lines, and contain the garrison. The fortress would be left to wither on the vine.

MacArthur would redirect forces originally planned for the Rabal invasion toward operations at Hollandia and Atipe in New Guinea. The schedule would be accelerated. They would reach the Philippines months earlier than previously planned. Holly would continue advancing through the Solomons, but avoid costly assaults on heavily defended positions.

The formal directive reached MacArthur’s headquarters in Brisbane on September 17th. MacArthur read it in his office overlooking the Brisbane River. His staff anxiously awaited his reaction. They had spent over a year meticulously planning to capture Rabul. Maps adorned the walls depicting landing beaches, phase lines, and objectives.

Intelligence files detailed Japanese defenses. Logistics plans, calculated shipping requirements, training programs, and prepared assault units were all now obsolete. MacArthur sat silent for several minutes. Then he summoned his chief of staff, Major General Richard Sutherland, and instructed him to begin replanning. The objective was no longer Rabol.

The objective was the Philippines. Rabol would be bypassed. Forces designated for the assault would be redirected to operations at Hollandia and Atape in New Guinea. Years later, MacArthur would claim in his memoirs that bypassing strong points had always been his strategy, that he had pioneered the concept, and that the Joint Chiefs had simply confirmed his tactical genius.

The historical record paints a different picture. MacArthur opposed the bypass until the Joint Chiefs ordered it. But MacArthur was intelligent enough to recognize when he had lost an argument and pragmatic enough to turn defeat into advantage.

MacArthur, despite his initial reluctance, would deliver the bypass operations the Joint Chiefs desired, but on an unprecedented scale. He would leapfrog across New Guinea, strategically bypassing and isolating entire Japanese armies, rendering them strategically insignificant. While Rubble was initially a key objective, the Philippines became his overriding focus. Rabel was relegated to a mere footnote in his grand strategy.

The ensuing 6 months demonstrated the bypass strategy’s effectiveness beyond expectations. The initial test commenced on November 1st, 1943 with 14,000 Marines from the third marine division under Lieutenant General Vandergrift’s command landing at Empress Augusta Bay on Bugenville. The Japanese garrison at Rabal, seeking to disrupt the landing, dispatched a cruiser force from truck to attack.

Admiral Hollyy swiftly countered by ordering carrier strikes directly on Rabal. On November 5th, Rear Admiral Frederick Coleman Sherman, a seasoned naval aviator with experience dating back to 1917, commanded Task Force 38 centered around the carriers Saratoga and Princeton. Sherman at 58 fully understood the inherent risks of deploying carriers against a heavily fortified land base.

Rabbal boasted over 300 anti-aircraft guns and the capability to launch hundreds of fighters. However, Hollyy’s orders were unambiguous. Neutralize the Japanese fleet before it could reach Buganville. At dawn on November 5th, Sherman launched 97 aircraft from his two carriers, 71 from Saratoga, and 26 from Princeton.

The strike force comprised Dauntless dive bombers, Avenger torpedo bombers, and Hellcat fighters. They flew 250 mi to Rabbal, arriving over Simpson Harbor at first light, catching the Japanese cruiser force completely at anchor and unprepared. The attack lasted a mere 18 minutes, but its impact was devastating. American dive bombers plunged through intense anti-aircraft fire, scoring direct hits on six of the seven heavy cruisers in the harbor.

The target go sustained near misses, resulting in 22 crewmen fatalities, including her captain. The Maya took a direct bomb hit in her engine room, causing 70 deaths. The Moami was engulfed in flames with 19 casualties. The Taco suffered two bomb hits and 23 deaths.

The Chuma and the light cruiser ANO sustained significant damage. By the time the American aircraft turned for home, the Japanese cruiser force was effectively crippled. Sherman lost nine aircraft and 14 airmen. Naval historians would later describe the attack as Pearl Harbor in reverse, marking the first successful carrier strike against a heavily defended land base.

Just 1 hour after the carrier strike, 27 B-24 Liberator bombers from General Kenny’s fifth Air Force escorted by 58 P38 Lightning fighters further pounded Simpson Harbor, exacerbating the damage. By the end of November 5th, the Japanese combined fleet had learned a harsh lesson. Simpson Harbor was no longer a safe haven. The damaged cruisers limped back to Trrook and the Japanese Navy never again deployed heavy surface ships to Rabbal.

Deprived of naval support, the Rabbal garrison could not effectively contest the Bugganville landing. The Marines established their beach head virtually unopposed. Within 3 weeks, they had constructed an airfield on Bugenville. On November 9th, Major General Roy Guyger arrived to assume command of the First Marine Amphibious Corps, relieving Vanderrift.

Guyger, a 58-year-old pioneer aviator within the Marine Corps, having flown since 1917, deeply understood the potential of air power to dominate the battlefield. Under his leadership, the Buganville airfield became fully operational in early December. American bombers immediately commenced strikes against Rabbal from 250 mi away, maintaining constant pressure.

The second major test occurred in late December when Marines landed at Cape Gloucester on the western tip of New Britain. This operation secured the straits between Cape Gloucester, New Britain and New Guinea, opening vital sea lanes for Allied shipping. The Japanese garrison at Rabble attempted to reinforce Cape Gloucester, but American submarines intercepted and sank two of the three troop transports before they could arrive. The third transport retreated.

The Cape Gloucester landing succeeded with minimal casualties. By January 1944, Rabbal was effectively surrounded. Allied airfields on Buganville, New Britain, and the Green Islands maintained relentless pressure on the base. Fighters patrolled over Rabal daily, shooting down any Japanese aircraft attempting to take off.

Bombers cratered the runways nightly, rendering them unusable. Despite repair efforts, Simpson Harbor transformed into a graveyard of sunken ships. Supply convoys ceased attempting to reach the base, and the 110,000 troops stationed there were effectively cut off. Other American commanders closely observed the events at Rabbal and grasped the strategic implications.

Admiral Chester Nimttz, commanding the central Pacific area, witnessed the success of the bypass strategy and applied it to the Marshall Islands. Instead of directly attacking heavily fortified bases at WA Maloyap and Millie, he bypassed them entirely, capturing the lightly defended Quadrilene and Enwok. The bypassed garrisons were isolated and unable to interfere with subsequent operations.

MacArthur adopted the same strategy in New Guinea, bypassing Japanese concentrations at Madang and Wiiwok and landing at Hollandia hundreds of miles to the west. The Japanese 18th Army found themselves surrounded by Allied airfields with no means to effectively retaliate. By March 1944, the bypass strategy had permeated the entire Pacific theater.

Planners no longer automatically assumed the necessity of capturing every enemy position. Instead, they began asking different, more strategic questions. Can we go around it? Can we isolate it? Can we achieve our objectives without directly fighting for this ground? Increasingly, the answer was affirmative. The statistics starkly illustrated the impact of the change in strategy.

In the 12 months preceding the Rabal bypass, Allied forces in the Southwest Pacific had suffered over 15,000 casualties while capturing positions of limited strategic value. In the 12 months following the bypass, casualties plummeted below 8,000 tollers, while the rate of advance more than doubled.

forces moved more swiftly, sustained fewer losses, and achieved more significant results. The nature of the Pacific War had fundamentally shifted. For the Japanese, this realization came slowly at first, then all at once. The first indication that something had changed occurred in late November 1943 when the Rabel garrison reported that American forces had landed on Buganville but were not advancing toward Rabal.

Imperial General Headquarters in Tokyo initially dismissed this as a diversion. Assuming the main attack would follow, they ordered the garrison to prepare for a full-scale invasion. However, the invasion never materialized. December passed, then January. The Americans continued to build airfields and relentlessly bomb Rabal, but they never landed troops.

By February 1944, Japanese commanders finally understood that they were being bypassed. 110,000 troops, the largest concentration of Japanese forces in the South Pacific, were marooned in a fortress that the enemy had deliberately chosen not to attack. Vice Admiral Janichi Kusaka, commander of the Southeast Area Fleet at Rabbal, a 52-year-old career naval officer who had overseen the construction of the airfields, tunnels, and defenses, had meticulously prepared for a decisive battle where American marines would storm the beaches and the garrison would fight to the last man. He

had never anticipated being simply ignored. Kusaka’s initial reaction was bewilderment. Why bypass such a strategically vital position? Robble controlled crucial sea lanes and posed a constant threat to any Allied advance. Leaving it intact seemed like a catastrophic error.

He waited for the inevitable invasion he believed was imminent. But as weeks turned into months, and the only Americans he saw were bomber crews at 20,000 ft, bewilderment gradually morphed into understanding. The Americans did not need to capture Rabbal. They had already defeated it. Without ships, Rabbal could not project power. Without aircraft, the airfields were useless. Without supplies, the garrison could not survive indefinitely.

Kusaka ordered his troops to cultivate gardens, grow their own food, and prepare for a siege that might last for years. He knew that the war was lost for Rabbal the moment the last supply convoy turned back in January 1944. Everything that followed was simply waiting. Other Japanese garrisons watched Rabbal’s fate unfold and felt their own strategic positions crumble.

At Trou the main fleet base in the Caroline Islands commanders realized that if the Americans could bypass Rabal, they could bypass Truck as well. They began evacuating the fleet westward. At Weiwok in New Guinea, the 18th Army remained entrenched in fortified positions, anticipating attacks that never came, while the Americans landed 400 m behind them at Hollandia. At Caviang on New Ireland, the garrison dug in and watched American ships sail past toward other targets.

The psychological impact of the bypass strategy was devastating. For two years, Japanese strategy had been predicated on defending key positions, holding islands, controlling sea lanes, and making every American advance so costly that they would be forced to negotiate a peace settlement. The bypass strategy shattered that logic.

It mattered little how well a position was fortified if the enemy simply circumvented it. It was irrelevant how many troops were concentrated in an area if those troops were unable to move. The defensive perimeter that Japan had painstakingly constructed over 2 years was exposed as an illusion. Japanese pilots reported a change in American tactics.

American ships appeared in unexpected locations. Bombers struck targets that should have been beyond their range. Marines landed on islands that should have been isolated. American forces moved at a pace that the Japanese were unable to match because the Japanese fleet was too damaged, aircraft too scarce, and supply lines too vulnerable. By mid 1944, Japan had lost its strategic mobility.

They could defend the positions they held, but they could not counterattack, reinforce threatened areas, or evacuate troops from bypassed garrisons. The Americans controlled both the sea and the air, giving them complete control over the pace and direction of the war. The reversal was complete.

In early 1943, Japanese commanders believed that Rabble was the key to maintaining control of the Southwest Pacific. By late 1944, Rubble had become a prison. $110,000 troops trapped in tunnels, cultivating vegetables in volcanic soil, awaiting relief that would never arrive. The Americans had defeated rubble without firing a single shot at it on the ground. They had achieved this by rendering it strategically irrelevant.

The bypass strategy received no formal recognition during the war. There were no ceremonies celebrating the decision not to invade Rabbal, and no medals were awarded for saving an estimated 20,000 lives by choosing not to engage in a costly assault. The Joint Chiefs issued a directive commanders implemented it and the war moved on.

General George Marshall returned to Washington after the war and served as Secretary of State and then Secretary of Defense. He was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1953 for the Marshall Plan, which played a critical role in rebuilding Europe. When historians inquired about the Pacific War, Marshall would state that the decision to bypass Rabal was one of the most important strategic choices of the conflict.

He estimated that it had saved tens of thousands of American lives and shortened the war by months. He never sought personal credit for the decision, emphasizing that it was a collective one made by military professionals who carefully considered casualty estimates and ultimately chose the path that preserved lives while achieving strategic objectives. General George Kenny remained in the Pacific until Japan surrendered.

He commanded the Far East Air Forces during the occupation retired in 1951 and later penned his memoirs. In his account, Kenny asserted that he had always believed that air power alone could neutralize rubble without the need for an invasion. He dedicated several chapters to describing how the fifth air force had bombed the fortress into strategic insignificance.

He mentioned the bypass decision almost in passing as if it had been the obvious course of action all along. However, historical records reveal that Kenny had vigorously argued for months that air power alone could accomplish the task and ultimately he was proven right.

Admiral William Holsey became a national hero. He returned home in 1945, was promoted to fleet admiral, and retired in 1947. He gave numerous interviews, wrote his memoirs, and made frequent appearances at Navy events. when questioned about Robblehy maintained that bypassing it was simply common sense once the casualty estimates became clear. No rational commander he asserted would throw Marines at a fortress when it could be circumvented.

He praised his staff for their meticulous planning and execution, but claimed full credit for implementing the first true bypass at Veila Lavella in August 1943, which he believed had demonstrated the viability of the concept.

General Douglas MacArthur, who commanded Allied forces until Japan’s surrender and subsequently oversaw the occupation, later commanded United Nations forces in Korea. In his memoirs published in 1964, MacArthur devoted considerable space to explaining how he had pioneered the bypass strategy. He wrote that he had always intended to avoid frontal assaults on fortified positions and that leaving enemy forces to wither on the vine was his own strategic innovation.

He mentioned the joint chief’s directive regarding Rabbal, but framed it as a confirmation of his own strategic thinking. However, historical documents indicate that MacArthur had initially opposed the bypass until the joint chiefs overruled him. By the time he wrote his memoirs, MacArthur had seemingly convinced himself otherwise. Rear Admiral Frederick Sherman, who had led the carrier strikes against Rabble on November 5th, continued to serve throughout the war.

He commanded carrier groups at Ley Gulf and Okinawa, retiring as a full admiral in 1947. In 1950, he published a memoir titled Combat Command, which included detailed descriptions of the rubble raid. Sherman wrote that attacking a land-based fortress with carriers was the riskiest operation he had ever commanded.

The success of that raid, he argued, proved that carrier task forces could strike anywhere at any time and survive. It profoundly changed how the Navy perceived carrier warfare. Sherman died in 1957. His Medal of Honor recommendation for the rubble raid was ultimately downgraded to a Navy cross, but his tactical innovations had a lasting impact on carrier doctrine for decades.

Vice Admiral Janichi Kusaka remained at Rabbal until Japan surrendered in August 1945. His garrison, isolated for 18 months, suffered catastrophic losses. When Australian forces entered Rabbal in September 1945, they found approximately 69,000 Japanese soldiers and 20,000 civilian workers still alive.

Over 20,000 had perished from starvation, disease, and malnutrition. The garrison had managed to sustain itself better than expected by converting to agriculture, growing rice, sweet potatoes, and tapioca in fields carved from the jungle. They also fished raised chickens and implemented strict rationing.

An Australian general at the surrender remarked that Rabel had essentially become like a small independent country. Kusaka was investigated for war crimes, but the evidence suggests that he was never convicted. Unlike General Hoshi Imamura, who commanded the 8th area army at Rabbal and received a 10-year sentence, Kusaka appears to have avoided prosecution.

He returned to Japan and published his memoirs in 1958 under the title Nothing New on the Rebel Front. He died in Kamakura on August 24th, 1972 at the age of 83. In interviews before his death, Kusaka stated that the worst aspect of Rabble was not the bombing or the starvation, but rather the waiting for an enemy that never came, the waiting for reinforcements that never arrived, and the waiting for a decisive battle that would give meaning to their sacrifice.

But the battle never happened. Brigadier General Kenneth Walker’s body was never recovered. He remains listed as missing in action. the highest ranking American officer never accounted for from World War II. His name is inscribed on the tablets of the missing at the Manila American Cemetery.

The Air Force named Walker Air Force Base in New Mexico in his honor. It operated from 1947 until 1967. Walker Hall at Maxwell Air Force Base in Alabama, home of Air University still bears his name. His Medal of Honor citation remains a testament to leadership by example, embodying the belief that commanders should share the dangers they order others to face.

Major Raymond Wilkins is buried at the Manila American Cemetery in the Philippines. His Medal of Honor was postumously presented to his family in 1944. The citation recounts how he led his squadron through the heaviest anti-aircraft fire that the fifth air force had ever encountered, destroyed two enemy vessels, and then made a final strafing run to protect his men at the cost of his own life. Wilkins flew 87 combat missions.

He died on his 87th mission. His squadron mates said that he could have remained on the ground after 80 missions, but he chose to continue flying because he believed that leaders should lead from the front. The physical remains of Rabbal still exist. The tunnels carved into the volcanic rock slowly fill with jungle vegetation.

The airfields are overgrown, the runways cracked and broken. The revetments collapsing. Simpson Harbor is now clear. The wrecks either salvaged or left to rust on the seabed. In 1994, volcanoes near Rabbal erupted, blanketing the town in ash and forcing the evacuation of the population.

The old Japanese base was buried under meters of volcanic debris, simultaneously preserving it and destroying it. There is a memorial at Rabal that commemorates the Australian soldiers who died defending the town in 1942. as well as the Allied airmen who died attacking it in 1943 and 1944. However, there is no memorial to the Japanese garrison that starved there.

Nor is there a plaque honoring General Marshall who advocated for bypassing the fortress or the members of the joint strategic survey committee who first proposed it or the thousands of Marines who did not die because someone had the wisdom to choose not to invade. The strategic lesson was learned and applied throughout the Pacific.

American planners utilized the bypass strategy at Truwak Cavang and dozens of smaller Japanese bases. Historians estimate that the strategy saved over 100,000 American casualties by avoiding unnecessary assaults on fortified positions. It accelerated the Allied advance toward Japan by months. It forced Japan to defend everywhere while being able to effectively attack nowhere, stretching their forces thin and rendering them ineffective.

This is how strategy truly evolves in war, not through the isolated brilliance of a single staff officer having a late night epiphany, but through the collective analysis of military professionals carefully weighing costs against benefits. Major Earl Hancock Ellis developed the theoretical framework in 1921. Admiral Raymond Rogers incorporated it into war plans in 1911.

The joint strategic survey committee applied it to Rabal in June 1943. General Marshall advocated for it against MacArthur’s initial resistance. General Kenny provided the crucial air power component. Admiral Hally implemented it first at Veila Lavella and then at Rabbal where the joint chiefs made it official policy.

And so 110,000 Japanese soldiers remained trapped in a fortress for 18 months defeated not by direct combat but by strategic irrelevance. If you found this story as compelling as we did, please take a moment to like this video. It helps us share more forgotten stories from the Second World War and stay connected with these untold histories.

Each one matters and each one deserves to be remembered and we would love to hear from you. Leave a comment below telling us where you are watching from. Our community spans from Texas to Tasmania. And from veterans to history enthusiasts, you are part of something special here. Thank you for watching and thank you for keeping these stories alive.

News

CH2 When Hitler Made A Fatal Mistake: The Moment The World Knows Of The Fall Of The Third Reich

When Hitler Made A Fatal Mistake: The Moment The World Knows Of The Fall Of The Third Reich The…

CH2 Why American Submarines Strangled Japan, While Japanese Subs Could Not Do Anything – The Man Who Bring Fears

Why American Submarines Strangled Japan, While Japanese Subs Could Not Do Anything – The Man Who Opened The Door …

CH2 German Submariners Were Astonished When Hedgehog Mortars Sank 270 U-Boats in 18 Months – The Key To This Is…

German Submariners Were Astonished When Hedgehog Mortars Sank 270 U-Boats in 18 Months – The Key To This Is… …

I Hid From My Family That I Had Won $120,000,000. But When I Bought A Fancy House, They Came…

I Hid From My Family That I Had Won $120,000,000. But When I Bought A Fancy House, They Came… …

At The Family Dinner, I Overheard The Family’s Plan To Embarrass Me At The New Year’s Party. So I…

At The Family Dinner, I Overheard The Family’s Plan To Embarrass Me At The New Year’s Party. So I… At…

My Parents Tried To Take My $4.7m Inheritance – But The Judge Said: “Wait… You’re…”

My Parents Tried To Take My $4.7m Inheritance – But The Judge Said: “Wait… You’re…” I didn’t expect the…

End of content

No more pages to load