The Atlantic Wall: Why Did Hitler’s “Greatest Fortification” Fail? – Newly Unearthed WWII Secrets Revealed

By 1944, Europe had transformed into a fortress built on fear, desperation, and illusion. To the German people, Adolf Hitler’s Atlantikwall—his so-called “Atlantic Wall”—was the crowning symbol of invincibility. Propaganda films showed endless lines of concrete bunkers, massive artillery batteries, and barbed wire snaking across the coast like an iron serpent guarding the continent. Posters boasted that no army on Earth could breach it, that this wall would hold the tide of invasion for a thousand years. The imagery was powerful, intoxicating even. But beyond the speeches and photographs, the truth was much darker, far more fragile. Beneath the concrete and steel, cracks had already begun to spread. Long before the first Allied soldier set foot on French soil, the wall was doomed—not from bombardment, but from arrogance, confusion, and the quiet erosion of reality within Hitler’s war machine.

The project began in earnest in 1942, the year Germany first felt the sting of vulnerability. The defeat in North Africa was still a whisper, and the Atlantic coast remained mostly untouched. But that summer, the Allies launched a raid on the French port of Dieppe—a small operation that would shape every military decision to come. Dieppe was supposed to be a test run, a quick strike to gauge German defenses. Instead, it became a massacre. As dawn broke, hundreds of landing craft pushed through the Channel fog, carrying mostly Canadian troops eager to prove themselves in their first major engagement. Within minutes, the beaches turned red. Machine guns hidden in concrete bunkers swept the shorelines. Tanks bogged down in wet sand, their treads spinning uselessly. Those who made it off the boats found themselves trapped against cliffs of steel and fire. By midday, the sea was littered with burning vessels and bodies. The raid collapsed in chaos. Out of the nearly 6,000 men who landed, more than half were dead, wounded, or captured.

The world saw the disaster as proof of German strength. Newsreels in Berlin showed columns of prisoners being marched through the smoking ruins of Dieppe, their uniforms darkened with blood, their faces a mix of exhaustion and disbelief. To the Allies, the lesson was brutal but clear: never attack a fortified port head-on again. But to Hitler, it was vindication. He saw Dieppe not as a warning, but as confirmation that his vision of an impenetrable fortress could work. In one of his rare moments of open pride, he declared before his staff, “No power on Earth will break the Atlantic Wall. It will stand for a thousand years.” That boast set into motion one of the largest construction projects in history.

Across occupied Europe, concrete poured day and night. Entire French villages were emptied to make way for bunkers and artillery emplacements. Millions of mines were buried beneath dunes and meadows, stretching from the icy fjords of Norway to the sun-bleached shores near Spain. Slave laborers from across the continent—Frenchmen, Poles, Russians, prisoners of war—worked under the lash of German overseers. They mixed cement until their hands blistered, carried rebar until their shoulders split, and died in shallow graves along the same beaches they were forced to fortify. The propaganda reels showed proud engineers and disciplined soldiers, but the true architects of the Atlantic Wall were these nameless, broken men.

Even as the project grew in scale, its foundation was weak. The sheer scope of it was absurd. Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt, the senior German commander in the West, studied the maps and realized the impossibility of what Berlin demanded. The wall stretched nearly 2,000 miles—an unbroken defense line that would have required millions of soldiers and unlimited resources to maintain. “We cannot defend every inch,” he warned. The Channel alone was 200 miles wide, and no army could guard every bay, every inlet, every strip of sand. Yet Hitler demanded just that. To the Führer, doubt was treason. Rundstedt’s warnings were ignored. The orders from Berlin were absolute: build, fortify, and prepare to fight to the last man.

Then came Erwin Rommel—the man soldiers called the Desert Fox. After his campaigns in North Africa, Rommel had earned a near-mythical reputation. His name alone struck both fear and admiration, even among his enemies. But when he arrived in France in late 1943 to inspect the Atlantic Wall, he found not a fortress but a façade. The reports he sent back to Berlin were blistering. He saw bunkers half-finished, trenches that filled with water at high tide, and defensive lines manned by old men and boys instead of seasoned troops. Machine guns were rusting. Artillery pieces were missing their ammunition. In many sectors, soldiers had never even fired their weapons. “This is not a wall,” Rommel muttered to his aides. “It is a delusion.”

What disturbed him even more was the pace of Allied preparations across the Channel. He knew from bitter experience what Allied air power could do. In North Africa, his armored divisions had been shredded by squadrons of British and American aircraft before they could even reach the front. He had seen entire columns of tanks turned into smoking wrecks within minutes. If the Allies ever landed in France, they would bring that same overwhelming air power with them. Any counterattack launched after the invasion would be annihilated before it reached the beaches. The only solution, Rommel insisted, was to stop the invasion at the water’s edge.

He threw himself into the work with manic urgency. Within weeks, construction intensified. He ordered six million mines to be laid, demanding that every beach be transformed into a death trap. Concrete tetrahedrons and steel spikes were driven into the sand to rip apart landing craft. Underwater obstacles were wired with explosives. He directed his engineers to plant “Rommel’s asparagus”—fields of tall wooden poles meant to destroy low-flying gliders before they could land. “The enemy must drown in blood before they reach the dunes,” he said grimly. His energy was unmatched, but even he could not outpace the war’s contradictions.

Rommel’s determination quickly clashed with the conflicting visions of his superiors. Field Marshal von Rundstedt, ever the traditionalist, believed that the Atlantic Wall should serve only as a buffer. He argued that the armored divisions should be held in reserve, stationed inland, where they could launch a massive counterattack once the true invasion site was revealed. Rommel disagreed violently. He insisted that keeping tanks inland was suicide. “By the time we move, the battle will already be lost,” he warned. “We must crush them before they get ashore.”

Hitler, as always, refused to choose. He listened to both men, nodding, then did what he so often did—nothing. The armored divisions were split between both strategies. Some were kept near the coast, others far inland, where they could neither support the beaches effectively nor respond quickly to an invasion. It was a decision born not of strategy, but of indecision, and it would haunt them in ways no one yet imagined.

As winter turned to spring in 1944, Germany’s attention was stretched thin. The Eastern Front consumed men and machines at a terrifying rate, while Allied bombers turned German cities into infernos. In the west, Rommel’s men worked feverishly, but they could not finish what Hitler demanded. Thousands of miles of coastline remained exposed. Ammunition was short. Concrete supplies dwindled. And the Luftwaffe—the once-mighty German Air Force—was now a shadow of its former self, unable to patrol the skies above France.

Across the Channel, meanwhile, the Allies were weaving a deception of breathtaking scale. In the fields of southern England, the ghosts of armies began to take shape. Inflatable tanks, wooden aircraft, and dummy landing craft filled the countryside. Entire airfields appeared overnight, their “planes” painted canvas stretched over wooden frames. The deception extended even to radio waves. Teams of British operators broadcast constant streams of false transmissions, simulating the chatter of an entire army group. It was all part of Operation Fortitude—a deception plan designed to make the Germans believe that the invasion would come not in Normandy, but at the Pas-de-Calais, the narrowest point between England and France.

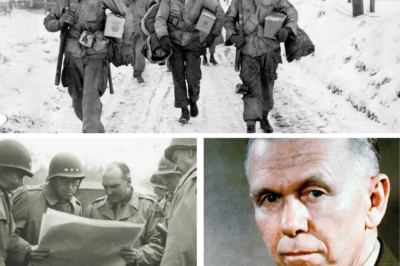

And to make the illusion perfect, they needed a face for this phantom army—a commander whose reputation would make the lie believable. They chose General George S. Patton. The Germans respected Patton more than any other Allied officer. They saw him as the embodiment of aggression, a man who would lead from the front and strike without hesitation. To them, it was inconceivable that such a commander would be anywhere but at the head of the main invasion force. And so Patton, kept out of the real operation for disciplinary reasons after slapping a soldier in Sicily, became the centerpiece of the greatest deception of the war. His name alone carried enough weight to convince German intelligence that the massive buildup in southeast England—complete with fake aircraft, vehicles, and supply depots—was real.

From Berlin to Calais, the reports confirmed it. The Allies, the Germans believed, would come across the narrow strait, strike the heavily defended coast of Calais, and drive straight toward Belgium and Germany. Normandy, with its rough seas, strong tides, and hedgerow country, was dismissed as unlikely, even absurd. To the high command, the Atlantic Wall stood ready, unbreakable, impregnable.

But deep down, even among the German officers who parroted the propaganda, unease was spreading. Those who had walked the beaches saw the gaps, the unfinished bunkers, the rusting guns. They saw young conscripts in ill-fitting uniforms manning positions meant for veterans. They saw the strain in Rommel’s face as he pushed for more resources that never came. And somewhere, beneath the surface of all the concrete and confidence, there lingered a silent question none dared to voice aloud: what if the wall was nothing more than an illusion?

The illusion that could crumble the moment the first wave hit the shore.

Continue below

By 1944, Europe had become a fortress of fear. On paper, Adolf Hitler’s Atlantikwall—his “Atlantic Wall”—was the greatest coastal defense project in history, stretching nearly 2,000 miles from Norway’s frozen fjords to the warm dunes of the French-Spanish border. Thousands of bunkers, millions of mines, and endless barbed wire turned the western edge of the continent into what Nazi propaganda called “the Shield of the Reich.” But beneath the grand claims and concrete, the wall was already crumbling before a single Allied soldier stepped onto French soil.

The seeds of its failure were sown long before D-Day.

In 1942, the humiliation at Dieppe shattered the Allied illusion that Germany’s coastal defenses could be taken by brute force. The raid—led mostly by Canadian troops—had turned the beaches into slaughterhouses. Hundreds were gunned down before they could even leave their landing craft. German cameras rolled as captured Canadians marched through the smoking ruins of Dieppe, their faces streaked with blood and disbelief. For the Allies, the lesson was brutal and unforgettable: never attack a port head-on again.

Hitler, however, drew the opposite conclusion. To him, Dieppe was proof that his walls worked. In a rare moment of personal pride, he told his architects, “No power on Earth will break the Atlantic Wall. It will stand for a thousand years.” And so the concrete poured. Entire French villages were emptied to make way for gun emplacements. Slave labor from occupied Europe dug trenches and laid mines until their hands bled.

But even as the wall grew, the cracks were already there—hidden beneath the Führer’s delusion. Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt, Germany’s Commander-in-Chief West, looked at the endless coastline and knew it was a fantasy. “We can’t defend every inch,” he warned Berlin. The Channel alone was 200 miles wide; there were not enough men, not enough tanks, and not enough ammunition to hold it all.

And then came Erwin Rommel—the “Desert Fox.”

Fresh from North Africa, Rommel arrived in late 1943 with scars of experience. He had seen what Allied air power could do. In the desert, he had watched squadrons of British and American planes tear his armored divisions apart before they could even engage. He knew the Allies ruled the skies, and that any counterattack by tanks after a beach landing would be slaughtered from above. To Rommel, the only solution was to crush the invasion at the water’s edge.

His inspections of the Atlantic Wall filled him with horror. Much of it was unfinished, outdated, and undermanned. He found empty pillboxes, flooded bunkers, and gaps wide enough for tanks to drive through. “The wall is nothing but propaganda,” he told his staff. Furious, he ordered 6 million mines to be laid and demanded every stretch of sand be turned into a killing field. Steel spikes, underwater traps, explosive obstacles—all were designed to tear apart the first wave of landing craft. “The enemy must drown in blood before they reach the dunes,” he declared grimly.

But Rommel’s urgency collided with Hitler’s arrogance and von Rundstedt’s caution. Rundstedt argued that tanks must be kept inland, ready to strike once the Allies revealed their true landing site. Rommel disagreed: “If we wait for the tanks to move, we will find only corpses at the coast.” Hitler, ever indecisive, split the difference—a decision that would doom them all.

In the spring of 1944, while the German high command quarreled, the Allies perfected their masterpiece of deception.

In Kent, England, fields were filled with dummy tanks made of rubber and wood. Inflatable trucks and fake landing craft dotted the countryside, visible to every German reconnaissance plane. Radio operators broadcast endless streams of fake chatter from a phantom force called the First U.S. Army Group—“FUSAG”—allegedly preparing to strike the Pas-de-Calais, the most obvious invasion point. And in charge of this imaginary army was none other than General George S. Patton—the man the Germans feared most.

Operation Bodyguard had begun, and it worked flawlessly.

Intercepted German intelligence confirmed it: Hitler and his generals were convinced the real invasion would come at Calais. Normandy, with its marshy terrain and long approach, seemed far less likely. The deception would cost Germany its western empire.

Meanwhile, across Britain, the greatest amphibious invasion in history was assembling in secrecy. Two million men—British, American, Canadian, and Free French—trained day and night on the coast. Shipyards thundered with the sound of welding as an armada of 5,000 vessels took shape. In the Scottish highlands, engineers tested bizarre inventions under the eye of General Percy Hobart—flamethrower tanks, mine-clearing flails, amphibious “swimming” Shermans, and bridge-laying behemoths. The troops called them “Hobart’s Funnies.” Churchill called them “our edge against Hell.”

And Hell was waiting for them in Normandy.

The German coastal units manning the Atlantic Wall were a mix of veterans, conscripts, and foreign soldiers pressed into service—Poles, Czechs, even Soviet POWs wearing German uniforms. Their morale was brittle. Many bunkers lacked radios; ammunition supplies were short. Rommel’s 7th Army stretched from Brittany to the Netherlands, and he knew it was a threadbare line against a tidal wave.

Still, he worked tirelessly, traveling from beach to beach, inspecting defenses, berating engineers, and planting explosives with his own hands. In letters to his wife, Lucie, he sounded almost desperate. “If they come now,” he wrote in May 1944, “we might still throw them back. If they come later—God help us.”

He was right about the timing.

By early June, the skies over the Channel were choked with storm clouds. Rain lashed the coast, and the tides turned savage. Meteorologists on both sides agreed: no invasion was possible. German commanders relaxed. Rommel took the chance to visit his family in Ulm, believing the weather would hold for days. His subordinates, General Friedrich Dollmann and Field Marshal Rundstedt, went about routine exercises, convinced the Allies would wait for better conditions.

But across the Channel, a quiet debate was raging in the nerve centers of Allied command.

Inside a cramped room in Portsmouth, General Dwight D. Eisenhower studied the latest weather reports. The invasion fleet—5,000 ships loaded with men, tanks, and supplies—was ready, waiting only for his word. Around the table, his commanders argued. The air chiefs warned that visibility was too poor for air support. The naval officers hesitated, fearing heavy losses in the storm.

For nearly an hour, no one spoke.

Then Eisenhower looked up and said four words that would change the course of history:

“Let’s go.”

The date was set: June 6, 1944.

Across southern England, soldiers were roused in the darkness. Chaplains walked through rows of tents, blessing young men barely old enough to shave. Letters were written and sealed. Engines rumbled to life as convoys of landing craft rolled toward the coast. At every port, men climbed aboard ships knowing that by this time tomorrow, many would be dead.

As night fell, the greatest armada ever assembled began to move. The sea boiled with the wake of thousands of vessels. The wind howled through the rigging, carrying with it the low murmur of prayers and the scent of salt and diesel.

On the beaches of Normandy, the German sentries heard only the storm and the crash of waves—never realizing that behind that curtain of wind and rain, history itself was coming for them.

The Atlantic Wall, Hitler’s pride and illusion, was about to meet its reckoning.

The Channel was alive with ghosts. In the early hours of June 6, 1944, as rain lashed the decks and waves rose like walls of steel, the Allied invasion fleet pressed on through the storm. Five thousand ships—destroyers, transports, landing craft, and gunboats—moved in a vast gray armada that stretched as far as the horizon. Every man aboard knew they were part of something that would either end the war or end them.

Above the clouds, unseen in the darkness, hundreds of aircraft roared east toward France. The first phase of Operation Overlord was underway. British and American paratroopers—men of the 82nd, 101st, and 6th Airborne Divisions—sat in silence, their faces painted black, their hands gripping weapons that felt suddenly too heavy. The wind rattled the fuselage of their planes, and each man stared at the red light above the door, waiting for it to turn green.

When it did, the sky exploded into chaos.

Parachutes blossomed like white flowers over the fields of Normandy, whipped by violent crosswinds. Many troopers missed their drop zones entirely, landing miles from their objectives. Some landed in flooded marshes, their heavy packs dragging them under. Others came down in the middle of German outposts and were gunned down before their boots touched the ground. But enough made it—scattered, disoriented, yet determined—to seize bridges, destroy communication lines, and sow confusion behind German lines.

In the small hours, near the village of Sainte-Mère-Église, Private John Steele of the 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment became tangled on the church steeple as his comrades fought below. Wounded and dangling, he watched the town burn beneath him while tracer fire streaked the sky. For two hours he hung there, playing dead as German soldiers passed beneath him. By dawn, American paratroopers had taken the village, and Steele—cut free at last—became one of the invasion’s first legends.

The same chaos repeated across the Normandy countryside. In fields, orchards, and hedgerows, isolated groups of paratroopers fought like wolves, ambushing convoys and cutting telephone lines. The Germans were thrown into confusion. Messages from command posts contradicted each other. Reports spoke of hundreds of parachutes scattered over dozens of miles, some real, some decoys dropped to further disorient the defenders. The deception worked: German officers had no idea where the main blow would land.

By 4:30 a.m., the rumble of engines at sea grew louder. The horizon to the north shimmered with faint light. In bunkers overlooking the beaches, German sentries rubbed their eyes and stared into the mist. The sea seemed alive—then the realization hit. Through the fog, the outlines of ships appeared. Dozens, then hundreds, then thousands.

The Atlantic Wall had awoken.

At 5:30 a.m., the bombardment began. Allied warships unleashed their guns in a deafening symphony that shook the coast to its foundations. The battleship USS Texas fired 14-inch shells that screamed across the water, smashing into concrete bunkers along Omaha Beach. British cruisers and destroyers pounded gun positions at Gold, Juno, and Sword. The entire Norman shoreline erupted in fire.

One German artillery officer at Pointe du Hoc later wrote, “The air turned to stone. We could not hear ourselves shout. We were buried alive, dug out, buried again. Men staggered through smoke like ghosts.”

When the guns fell silent, a new sound replaced them—the low growl of engines and the rhythmic slap of waves. The landing craft were coming.

The first wave of American soldiers approached Utah Beach just after 6:00 a.m. Strong currents had pushed them nearly a mile off course, but by accident, it saved them. They landed in a lightly defended sector. Brigadier General Theodore Roosevelt Jr., son of the former president, waded ashore with a cane in one hand and a pistol in the other. Seeing his men land in the wrong place, he famously shouted, “We’ll start the war right here!” Within two hours, the Americans had pushed inland and linked up with paratroopers from Sainte-Mère-Église. Utah was secure.

But twenty miles east, at Omaha Beach, disaster unfolded.

The Americans of the 1st and 29th Infantry Divisions were met by a wall of fire the moment their ramps dropped. Machine guns raked the surf. Mortar shells fell like rain. Many soldiers drowned under the weight of their packs before even reaching shore. Those who made it found no shelter—only open sand and the deadly crossfire of MG-42s mounted in concrete bunkers high above.

Private Charles Shay, a medic from Maine, remembered pulling men out of the surf, their faces pale and eyes lifeless. “The sea was red,” he said. “It was as if the ocean itself was bleeding.” Tanks meant to support the landing had been launched too far out. One by one, they sank beneath the waves, leaving the infantry alone.

For hours, chaos ruled Omaha. Officers were dead, radios destroyed, units scattered. The beach was a slaughterhouse. But amid the carnage, pockets of men began to move. Engineers blew gaps in the wire. Rangers scaled the cliffs with grappling hooks and bayonets, silencing German guns that had turned the beach into hell. Slowly, painfully, the tide turned. By afternoon, Omaha was a graveyard—but it was also in Allied hands.

At Gold, Juno, and Sword Beaches, the British and Canadians faced their own nightmares. At Gold, men of the 50th Division met fierce resistance from the German 352nd Infantry. Tanks floundered in deep water, and the first landing craft were shattered by mines. But Hobart’s “Funnies”—the flail tanks, bridge layers, and flame throwers—did their work. By noon, the British were moving inland, capturing the village of Arromanches, where within days they would build the first of the artificial “Mulberry” harbors.

At Juno, the Canadians were cut down as they stepped from their craft, but those who survived stormed forward with ferocity born of vengeance. Many had fathers or brothers killed at Dieppe. They would not be stopped again. By nightfall, they had taken their objectives and pushed deeper into France than any other Allied force that day.

Sword Beach, on the eastern flank, saw the British 3rd Division storm ashore under cover of naval gunfire. They moved swiftly, linking up by afternoon with paratroopers of the 6th Airborne who had seized the bridges over the Orne River and the Caen Canal. Among them was Major John Howard, whose men had landed in wooden gliders in total darkness, capturing their objectives in just fifteen minutes. It was one of the most flawless operations of D-Day.

By midday, the impossible had happened: the Atlantic Wall had been breached.

From his headquarters near Paris, Field Marshal Rundstedt received frantic reports from Normandy. Confused signals, contradictory accounts, and pleas for reinforcements poured in. But the one man who could authorize the release of the Panzer divisions—the only units capable of driving the Allies back—was asleep. Hitler’s aides refused to wake him.

When the Führer finally awoke near noon, the battle was already lost. Convinced the Normandy landings were a diversion, he refused to commit his armored reserves. He was certain the main attack would come at Calais. “Hold the line,” he barked into the phone. “The real invasion is yet to come.”

At the front, Rommel’s absence was felt like an open wound. His subordinate, General Dollmann, hesitated, awaiting orders that never came. When Hitler finally gave permission to move the Panzers, it was too late. Allied bombers had already destroyed bridges and rail lines. The tanks crawled toward the coast, strafed at every turn by Typhoons and Mustangs screaming down from the clouds.

By nightfall on June 6, over 150,000 Allied soldiers stood on French soil. Behind them stretched an ocean of ships, bringing more men, more tanks, and more guns. Ahead of them lay the bocage—the hedgerow labyrinth of Normandy—and the long road to Paris. But for the men who had lived through the beaches, one truth had already taken shape: the Atlantic Wall had not failed because it was weak. It had failed because it had been built on lies.

In a damp bunker near Caen, a wounded German lieutenant wrote in his diary that night:

“They told us the Wall was invincible. They told us no enemy could land. But today I saw the sea burning, and the Wall swallowed by the tide. We are alone now.”

That night, Eisenhower stood on the bridge of his command ship, looking out across the dark water. Fires still burned along the coast, the air thick with smoke and salt. Behind him, a messenger handed him the first confirmed report: the beaches were secure.

He read it silently, then turned to his officers. “Well, gentlemen,” he said quietly, “we’re in France.”

And somewhere in the blackness beyond the horizon, Hitler—still clinging to his delusions—had no idea that his thousand-year fortress had crumbled in a single day.

The Atlantic Wall had fallen, and the road to Europe had opened.

The morning after D-Day smelled of smoke, salt, and death. The beaches of Normandy were no longer places of sand and surf—they were graveyards of machines and men. Burned-out landing craft lay half-buried in the tide. Tanks, still smoldering, leaned like toppled monuments to the price of victory. The sea had carried everything—corpses, helmets, rifles, shattered timber—back onto the shore, as if the Channel itself refused to keep the evidence of what had happened.

But behind the devastation, the impossible had been achieved. The Allies had landed on the continent. The Atlantic Wall, Hitler’s “unbreakable” defense, was nothing more than a broken line of bunkers half-swallowed by smoke. Yet even as the first waves of victory rippled through the Allied ranks, those on the ground knew the real battle was only beginning.

Inland from the beaches stretched the bocage—Normandy’s countryside of hedgerows, narrow lanes, and tiny fields enclosed by earthen embankments. To an untrained eye, it was beautiful—green and peaceful, dotted with orchards and stone farmhouses. But to the soldiers now pushing forward, it was a death trap. German snipers, machine-gunners, and mortars turned every hedge into a fortress. Tanks could barely maneuver. Infantry advanced only yards at a time. It was, as one American sergeant put it, “a thousand small wars fought in the mud.”

In the British sector, General Bernard Montgomery’s troops faced the worst of it. Their target was Caen, a key crossroads city that Rommel had declared vital to the defense of France. “If Caen falls,” he told his staff, “so does Normandy.” The British 7th Armoured Division—the famous Desert Rats—rolled toward the city with confidence. But within hours, they ran headlong into German Tiger tanks of the 21st Panzer Division. The Tigers were monsters—70 tons of steel and arrogance, their 88mm guns capable of ripping through any Allied tank from over a mile away.

The Sherman tanks that Montgomery’s men relied on were no match. The Germans nicknamed them Tommy cookers, because when hit, they erupted into flames like matchsticks. In one five-minute exchange outside the village of Villers-Bocage, ten British tanks were destroyed before they could fire a single effective shot. Survivors crawled through hedgerows under machine-gun fire, their radios filled with the screams of burning crews.

Montgomery called for air support, but the weather had turned again. Thick clouds rolled in from the Channel, grounding aircraft and turning the battlefield into a quagmire. Rain turned the fields into lakes of mud. “We were fighting ghosts in fog,” one British corporal recalled. “You never saw the enemy until he shot you.”

By nightfall, the attack on Caen had stalled. The city remained firmly in German hands.

Meanwhile, to the west, American forces were making slow progress toward the port of Cherbourg. They needed it desperately; without a major harbor, reinforcements and supplies could not sustain the growing army. The artificial “Mulberry” harbors—massive concrete caissons towed from England and sunk off the beaches—were miracles of engineering. But nature had its own agenda. On June 19, a violent storm swept across the Channel, smashing ships and tearing the American Mulberry at Omaha to pieces. Within hours, the makeshift harbor was destroyed.

Supplies piled up on the beaches. Crates of ammunition, fuel, and food sat exposed to the rain, useless until the port could be opened. The only functional Mulberry left was at Arromanches in the British sector, and it strained under the weight of the entire invasion’s logistics. Eisenhower’s staff called the storm “our second Dieppe.”

In Cherbourg, German defenders fought with suicidal determination. Their orders from Hitler were clear: Hold at all costs. They turned the city into a maze of rubble and traps. American soldiers fought house to house, sometimes room to room. “Every corner had a gun behind it,” one GI wrote in his letter home. “Every basement was a bunker.” When the Germans finally surrendered on June 29, the city was a ruin. The docks were deliberately destroyed, cranes blown apart, the harbor filled with sunken ships. It would take another month to clear the wreckage.

The campaign was dragging into its fourth brutal week, and the men were exhausted. The joy of D-Day had faded into fatigue and frustration. The hedgerows, the rain, and the endless counterattacks made each mile of advance feel like a mile of hell. “We took a field one day,” a Canadian officer remembered, “and gave it back the next morning with twice as many dead.”

Still, the Allies pressed on.

Montgomery launched Operation Epsom at the end of June—an attempt to encircle Caen from the west. Thousands of British and Scottish infantrymen advanced behind a rolling artillery barrage, their boots sinking into knee-deep mud. They captured several villages but soon ran into the full fury of the II SS Panzer Corps, newly arrived from the Eastern Front. The fighting was merciless. In one 48-hour period, 5,000 British soldiers were killed or wounded. “The ground was a slaughterhouse,” a German panzer officer later admitted. “We fought until the barrels of our guns glowed red.”

Even Rommel, returning from his brief trip to Germany, was stunned by what he found. The coast he had prepared so meticulously was gone—obliterated. The Atlantic Wall he had built was nothing but scattered ruins. Now the war had moved inland, into terrain where his once-feared Panzers could barely maneuver. The Allies, with their overwhelming air power, ruled the skies. Convoys of German trucks and tanks were reduced to burning husks on the roads. Each day, the Luftwaffe grew weaker, its pilots outnumbered and outgunned.

But Rommel’s greatest battle wasn’t just with the Allies—it was with his own Führer. He begged Hitler to allow a withdrawal from Normandy to regroup along the Seine River, arguing that the front could not hold. Hitler refused. “Not one step back,” he ordered. “The Atlantic Wall will be defended where it stands—or it will bury you all.”

Rommel knew then the war was lost.

On July 17, while returning from the front, his staff car was strafed by Allied fighters near Vimoutiers. A burst of machine-gun fire shattered the windshield and sent the car careening into a ditch. Rommel was thrown out, his skull fractured, his face cut to ribbons by glass. He was unconscious for hours. When he awoke in a field hospital, he could barely speak. The Desert Fox—the only German commander the Allies truly respected—had fought his last battle.

While Rommel lay recovering, another battle was raging far from Normandy—one that would shake Hitler’s confidence to its core.

On July 20, 1944, inside the Wolf’s Lair in East Prussia, Colonel Claus von Stauffenberg placed a bomb beneath the conference table during a meeting with Hitler. Minutes later, it exploded. The blast killed four men and ripped through the bunker like thunder. But fate intervened: the heavy oak table leg shielded Hitler from the full force. He escaped with minor burns and a broken eardrum.

The failed assassination attempt—Operation Valkyrie—sent shockwaves through Germany. Hundreds of officers were arrested. Stauffenberg was executed by firing squad the same night. Others were hanged with piano wire, their deaths filmed for Hitler’s amusement. The Führer emerged from the ordeal more paranoid and vengeful than ever. He purged the army’s upper ranks, replacing cautious professionals with fanatics. From that point on, every German order in Normandy came directly from Hitler’s bunker—delayed, confused, and disconnected from reality.

By late July, the Allies finally had the momentum they needed. The German army, battered and undersupplied, was running out of men and machines. The Americans prepared a massive offensive—Operation Cobra—to break through the last German lines south of Saint-Lô.

At 9:30 a.m. on July 25, more than 1,800 Allied bombers darkened the sky. The roar of engines was deafening. They dropped thousands of tons of explosives on a four-mile stretch of front line. The bombardment was so intense that it stunned even the hardened infantrymen waiting to advance. When the smoke cleared, the ground looked like the surface of the moon—blackened, cratered, lifeless.

But not all the bombs fell where they were supposed to. Some veered short, landing on American positions. Over a hundred U.S. soldiers were killed by their own air force in a storm of friendly fire. Still, when the order came to advance, they moved forward. Through smoke and ash, they marched straight into history.

At first, the Germans held. Then, suddenly, their defense collapsed.

American Sherman tanks surged through the gaps. Infantry poured in behind them. The German front, weakened by constant bombardment and confusion in command, simply disintegrated. Within 48 hours, the Americans had achieved what the Allies had fought six bloody weeks for: a breakout.

The hill town of Coutances fell, then Avranches, opening the road south. For the first time since D-Day, the Allies were no longer trapped behind the hedgerows. Ahead of them stretched open country—fields, highways, and towns leading straight to the heart of France.

But in Berlin, Hitler refused to see the truth.

He issued frantic orders for counterattacks, demanding the remnants of his Panzer divisions strike west to cut off the Americans. “Drive them into the sea!” he screamed during one of his nightly rants. But his generals no longer believed him. Rundstedt, weary and defeated, told Berlin simply: “Make peace, you fools.” For his honesty, Hitler dismissed him on the spot.

The same day, Rommel, recovering at home, learned his name had been linked to the July 20 plot. The Gestapo would come for him soon.

The Atlantic Wall was gone. The German army in Normandy was breaking apart. And as the Allies raced through the gap, a city waited to be liberated—a city that had endured four years under the swastika.

The next phase of the battle would not be fought for beaches or hedgerows, but for Paris itself.

By August 1944, the once-mighty German Army in the West was collapsing like a dying beast. The thunder of Allied armor rolled through the Norman countryside, leaving shattered Panzers smoldering in hedgerows and the twisted remains of Hitler’s Atlantic Wall far behind. The wall that was supposed to stop an invasion had done nothing but delay the inevitable. And now, what remained of Hitler’s western army was running out of time, out of roads, and out of places to run.

For the men of the Wehrmacht trapped in Normandy, the sky itself had turned against them. Allied aircraft dominated the air day and night. Thunderbolts and Typhoons swooped down in endless waves, ripping convoys to shreds with rockets and machine guns. German drivers abandoned their vehicles and fled into the fields, where bombs and napalm followed them. “It was not a battle,” one German survivor recalled. “It was an extermination.”

The Allies had achieved what every commander since Caesar had dreamed of—complete control of northern France. But they weren’t finished. Their next move would destroy what was left of Hitler’s army in the West.

The plan was simple, and merciless.

While the British and Canadians under General Montgomery pressed south from Caen, American forces under General Omar Bradley and George S. Patton swung wide through the west, turning eastward in a great sweeping arc. Between them lay tens of thousands of German soldiers retreating through a narrowing corridor near the towns of Falaise, Argentan, and Chambois. The Allies called it the Falaise Pocket. The Germans would call it the “Valley of Death.”

By mid-August, the jaws of the trap began to close. The 7th Army and the 5th Panzer Army—Hitler’s last strong forces in France—were packed into a shrinking pocket of farmland and villages. For three days, Allied artillery poured shell after shell into the cauldron. American aircraft bombed every road, bridge, and column that tried to escape. Civilians fled in terror as whole villages disappeared under fire.

Inside the pocket, chaos reigned. German convoys clogged every road, horses and men tangled in burning wreckage. Officers screamed orders no one could follow. “We were like rats in a box,” wrote one German lieutenant. “The ground burned beneath our boots.” The smell of diesel and death filled the air. By August 19, Allied forces had completely sealed the pocket.

For the next 48 hours, it was slaughter.

American artillery from the west and Canadian guns from the north turned the valley into a sea of flame. Columns of German armor—what remained of once-proud divisions—were obliterated where they stood. When the shelling stopped, the survivors tried to flee on foot, abandoning their vehicles and crawling through the fields under strafing fire from Allied planes.

When the smoke finally cleared, the Allies counted over 10,000 German dead. More than 50,000 surrendered. Thousands more vanished—burned, buried, or simply erased. The roads from Falaise to Chambois were lined for miles with the wreckage of an army: blackened tanks, overturned trucks, bloated horses, and the shattered bodies of men who had once believed the Atlantic Wall would protect them.

A British war correspondent described the scene in his notebook:

“I have seen battlefields before, but never like this. The valley stinks of fuel and death. You walk on corpses. Tanks lie on their sides like dead whales. The air hums with flies. It is as if the earth itself is rejecting what man has done to it.”

For Hitler, the defeat at Falaise was beyond comprehension. He refused to believe the reports. “The Western Front is stable,” he told his generals in Berlin. “It is a temporary setback.” But even his most loyal officers could no longer hide the truth. The armies that had once defended France were gone. The survivors were scattered, exhausted, and broken.

The path to Paris was open.

In early August, while the fighting still raged in Normandy, the French Resistance in Paris began to rise. News of the Allied advance had spread through the city like wildfire. By the 19th, the streets were in open rebellion. Barricades went up overnight. Police stations were seized. Trains were derailed, bridges sabotaged, German patrols ambushed. The tricolor flag—banned for four years—flew once more over the city’s rooftops.

In the Hôtel de Ville, the city hall, the underground leaders of the Resistance gathered under General Henri Rol-Tanguy. They sent frantic messages to the Allies: “Paris is fighting. Paris needs help.”

General Eisenhower faced a terrible choice. Paris was a trap waiting to happen. The city’s narrow streets favored defenders, and Hitler had already issued his infamous order: “If Paris is to fall, it must not fall intact. It must be reduced to rubble.” Bridges, rail yards, and monuments had been rigged with explosives. The Allies feared that if they entered the city too soon, it would become another Stalingrad—a bloody siege in the heart of civilization.

But Charles de Gaulle, the proud leader of the Free French, would not allow it. “Paris,” he said, “is not just a place. It is the soul of France. It cannot wait.” He demanded that French troops lead the liberation. Eisenhower, after long hesitation, agreed. The French 2nd Armoured Division under General Philippe Leclerc was given the honor.

On August 24, Leclerc’s columns—Sherman tanks draped in the French flag—rolled through the southern suburbs. Crowds poured into the streets, weeping, shouting, throwing flowers onto the tanks. The next day, they entered the city itself.

Gunfire echoed down the boulevards as Resistance fighters battled the last pockets of German troops. Smoke rose from the Prefecture of Police, where the tricolor waved defiantly from the roof. By afternoon, the German commander of Paris, General Dietrich von Choltitz, realized the end had come. Disobeying Hitler’s orders to destroy the city, he surrendered.

At 3:30 p.m. on August 25, 1944, the bells of Notre-Dame rang out across Paris. For the first time in four years, they rang not for the Reich, but for freedom.

De Gaulle entered the city the next day, marching down the Champs-Élysées through a blizzard of cheers and tears. “Paris!” he declared from the Hôtel de Ville balcony, his voice thundering through the crowd. “Paris! Outraged, broken, martyred—but Paris, liberated by her own people, with the help of the armies of France, with the support and help of all of France!”

The crowd roared. The sound rolled down the streets and out across the Seine, where the ruins of the German occupation still smoldered. The city that Hitler had sworn to destroy still stood. His “Thousand-Year Reich” had lasted barely twelve years.

In Berlin, the news of Paris’s liberation hit Hitler like a physical blow. Witnesses said he flew into a rage so violent that his staff feared for their lives. He screamed at his generals, blamed the Luftwaffe, cursed Rommel—whom he now suspected of treachery—and even accused the Almighty of betrayal. “The war is lost because no one believes in me anymore!” he shouted. “But I will never surrender.”

He was right about one thing. He would never surrender.

As the Allies swept across France, German resistance crumbled. Town after town greeted the advancing armies with flowers and tears. In Brittany, in Alsace, in Lorraine—Frenchmen poured into the streets waving flags that had been hidden for years in attics and cellars. In the cafés of newly liberated towns, soldiers toasted with stolen wine and sang songs of victory, though they knew the road to Berlin would be long and bloody.

By September, the remnants of the German army had retreated beyond the Seine, trying to regroup. The Allied advance slowed as supply lines stretched to the breaking point. But the impossible had already been done. In less than three months, the Allies had crossed the Channel, breached the Atlantic Wall, liberated Normandy, destroyed the German army in the West, and freed Paris.

The wall that Hitler had once called “impregnable” had fallen like wet paper.

Later, when Allied engineers surveyed the ruins of the Atlantic Wall, they found bunkers half-finished, concrete so poor it crumbled under a shovel. Many of the coastal guns were rusted, their barrels pointed uselessly at the sea. “It was never a wall,” one British officer said quietly. “It was a lie made of stone.”

For the Germans who built it—hundreds of thousands of forced laborers from across occupied Europe—it had been a monument to slavery. For Hitler, it had been a monument to his delusion. For the men who stormed through it on June 6, 1944, it became a symbol of something greater: proof that even the mightiest empire built on fear could fall in a single dawn.

As autumn fell over France, the Allies prepared for the next phase—the crossing of the Rhine and the push into Germany itself. Eisenhower, exhausted but resolute, stood before a map marked with the red arrows of his armies and said simply, “We’ve broken his wall. Now we’ll break his will.”

In Berlin, Hitler retreated deeper into his bunker, surrounded by lies, loyalists, and the sound of a world collapsing above him. His Atlantic Wall was gone. His empire was dying. And the war he had unleashed on humanity was closing in on him from every direction.

The greatest fortification ever built had failed not because the enemy was stronger, but because truth was stronger than tyranny.

And as the last echoes of battle faded across the fields of Normandy, one message—written in the blood and courage of thousands—remained carved forever in history:

No wall, however high, can stop those who fight for freedom.

News

CH2 When Japan Fortified the Wrong Islands… And Paid With 40,000 Men – How 40,000 Japanese Soldiers Fell Without a Fight When America Outsmarted the Fortress Islands of the Pacific

When Japan Fortified the Wrong Islands… And Paid With 40,000 Men – How 40,000 Japanese Soldiers Fell Without a Fight When…

CH2 Myth-busting WW2: How an American Ace Defied the Odds and Became a Legend of the Skies, Stealing A German Fighter And Flew Home And Shocked the World – Is It True Or Just A Myth

Myth-busting WW2: How an American Ace Defied the Odds and Became a Legend of the Skies, Stealing A German Fighter…

CH2 3,000 Casualties vs 3 – The Deadliest Trap of WW2 Laid By One 19-Year-Old’s Codebreaking and a Midnight Naval Ambush

3,000 Casualties vs 3 – The Deadliest Trap of WW2 Laid By One 19-Year-Old’s Codebreaking and a Midnight Naval Ambush…

CH2 The Secret That Changed WAR FOREVER: How America’s “Counterattack Instinct” Rewrote the Rules of Battle and Crushed Hitler’s Armies While Other Allies Took Cover First

The Secret That Changed WAR FOREVER: How America’s “Counterattack Instinct” Rewrote the Rules of Battle and Crushed Hitler’s Armies While…

CH2 ‘You’ll Never Find Us!’ Japanese Captain Laughs in the Fog—But American Radar Sees All, Turning the Solomon Sea Into a Death Trap

‘You’ll Never Find Us!’ Japanese Captain Laughs in the Fog—But American Radar Sees All, Turning the Solomon Sea Into a…

CH2 THE FORK-TAILED THUNDER: The Untold Rise, Fall, and Redemption of the P-38 Lightning — America’s Most Misunderstood Fighter of World War II

THE FORK-TAILED THUNDER: The Untold Rise, Fall, and Redemption of the P-38 Lightning — America’s Most Misunderstood Fighter of World…

End of content

No more pages to load