The 96 Hour Nightmare That Destroyed Germany’s Elite Panzer Division

July 25th, 1944. 0850 hours. General Leutnant Fritz Berlin crouched in the rubble of what had been his forward command post, the walls of the farmhouse reduced to splintered beams and scattered bricks. The bombardment had been unrelenting for forty minutes, and even in the shadow of ruined walls, he could feel the tremors in the earth beneath him, each detonation sending shivers up through the soles of his boots. Outside, the fields that had once housed the division’s proud Panthers now burned, twisted hulks of armor lighting the smoke-filled air with flickers of orange and black. Around him, the elite division, the one that had trained nearly every Panzer officer in the Wermacht, seemed to evaporate before his eyes—not by enemy strategy, not by a superior armored force, but by a force he could not anticipate, one that seemed almost supernatural in its persistence and destruction. He could do nothing but watch, immobilized not by fear, but by the cruel reality that every defensive measure, every tactical insight, had been rendered powerless. Within hours, the true scale of the disaster would become unmistakable, a lesson that no staff college had ever prepared him to confront.

The morning had dawned with the deceptive calm that sometimes preceded chaos. At 0650 hours, Fritz Berlin had stood at the threshold of his command post, a reinforced farmhouse near Marini in Normandy, scanning the horizon. The sky, once a protective blanket of low, grey clouds, had begun to lift, exposing the world below to the full glare of the sun. With the clearing skies came a new threat: the relentless dominance of Allied airpower. The Panzer divisions, who had weathered storms of artillery and infantry assaults with tactical finesse, now faced enemies who could strike from above with impunity. Berlin was a man of meticulous precision. At forty-five, he embodied every ideal of the Wermacht’s officer corps. He was a Knight’s Cross holder with oak leaves and swords, a decorated veteran whose service had spanned North Africa under Raml and the brutal campaigns of the Eastern Front. He had survived Poland, France, and Russia by mastering a single principle: anticipate the enemy’s advantage and neutralize it with superior positioning and maneuvering. Yet in Normandy, even that principle faltered against an opponent whose advantage was not just in numbers or firepower, but in resources that seemed almost limitless.

For a month, the division had been committed as an armored reserve in the defense of Normandy, and in that time, the once-mighty unit had been slowly dismembered. Each engagement, each counterattack, had been absorbed and nullified by an enemy with unmatched logistical support, who could replace losses faster than they could be inflicted. The division that had left Chartres on June 7th with 316 operational tanks now fielded only 93. The fuel trucks that had once carried 350,000 liters of gasoline were dwindling to nothing, their drivers increasingly scarce and their convoys prime targets for airstrikes. Ammunition trains had been decimated, leaving artillery and tanks with only the barest stockpiles of shells, incapable of sustaining even a single prolonged engagement. Repair workshops, once the lifeblood of a mechanized division, had shut down under the relentless pressure of damaged vehicles and lack of spare parts. The professional soldiers, the elite crews whose skill had been the envy of the Wermacht, were being ground down, attrited day by day by constant bombardment, air attacks, and the impossibility of reestablishing supply lines.

Berlin had seen war in its many forms—trench assaults in Poland, the fluid mobile warfare across France, the harsh winters on the Eastern Front, and the deserts of North Africa—but nothing in his experience had prepared him for this new type of warfare. The enemy did not merely engage in battle; they erased the foundations of his division’s existence before the first shot could even be fired. Tanks burned before reaching the frontline, trucks were strafed from the sky, and repair crews were destroyed in their garages. The division was not simply being attacked—it was being systematically strangled. Every morning, Berlin awoke with the hope that some strategic advantage, some unanticipated maneuver, could restore order, but by midday, he faced the sobering truth: the enemy’s resources were endless compared to his own.

Yet even amid the chaos, there was a glimmer, however faint, of possibility. The soldiers of Panzer still carried the legacy of the division’s training and discipline, the cohesion of men who had survived campaigns across continents. In theory, a concentrated strike, a perfect coordination of remaining tanks and infantry, might still achieve something. The enemy’s superiority in numbers and supply might be momentarily mitigated by clever positioning or daring execution. Berlin, ever the tactician, understood that such opportunities were fleeting, and he knew that each decision, each command, would have to be made with absolute precision. Every burned tank and every empty fuel drum reminded him that time was a luxury they could no longer afford.

The air around him was thick with smoke, the acrid stench of burning metal and fuel filling his nostrils. The soundscape was dominated by explosions, the whistle of falling shells, and the distant drone of Allied aircraft returning for another pass. For the men around him, the psychological toll was immense. Even the most experienced crews, those who had survived countless battles across Europe, were showing signs of strain. Coordination was faltering. Discipline was being tested to its limits. Yet amidst the fear and exhaustion, there was a shared understanding: they were witnessing the collapse of what had been considered the Wermacht’s finest division, a unit that had trained others in the art of armored warfare, now reduced to fragments under relentless pressure.

In that moment, Berlin realized the scale of the nightmare. This was no longer a battle that could be managed through tactical acumen alone. It was a war of resources, logistics, and industrial capacity—a confrontation where skill mattered less than fuel, ammunition, and the ability to replace losses faster than they were inflicted. He thought back to the division’s proud history, the careful drills, the coordinated maneuvers, the painstakingly maintained vehicles, all brought low not by the courage of the enemy, but by the invisible machinery of a well-supplied adversary that could strike with unceasing efficiency.

And yet, for all the destruction surrounding him, there remained a sliver of hope, fragile and tenuous. Berlin knew that the division still contained men capable of decisive action if the conditions allowed. He understood that the enemy, as overwhelming as they appeared, was not invincible. In those next hours, every decision he made, every movement ordered, would either preserve the remnants of the Panzer division or see it vanish entirely. The morning had begun with a sense of grim determination, and now, as the bombardment continued unabated, Berlin prepared to act with the precision and calculation that had defined his career.

The stage was set for what would become a 96-hour ordeal, a concentrated period of relentless pressure that would strip away the veneer of invincibility from Germany’s elite armored forces. The Panzer division, once the pride of the Wermacht, faced a reality where skill, experience, and courage could only go so far. The enemy’s supremacy in logistics, airpower, and relentless operational tempo had created a situation Berlin could not simply maneuver around. Each hour brought new losses, new obstacles, and the stark understanding that the war they had trained for was now being fought on terms dictated by the opponent, not by strategy or doctrine.

And now, finally, there was a chance.

Continue below

July 25th, 1944. 0850 hours. General Litnant Fritz Berlin crouched in the rubble of what had been his forward command post. The bombing had been continuous for 40 minutes. The ground was still trembling with each new explosion. Panthers burning in fields around him. His division, the elite panzer lair, the demonstration division that had trained all the others, was disappearing.

Not from enemy tanks, not from superior tactics. Something else was destroying them. He couldn’t stop it. He couldn’t fight it. He could only watch. And within hours, he would understand something that no amount of staff college training had prepared him for. The morning had seemed full of possibility. July 25th, 1944, 0650 hours.

General Utnant Fritz Berlin stood at the entrance of his command post, a reinforced farmhouse near Marini in Normandy, studying the morning sky. The weather that had protected Panzer division for the past month was breaking. Cloud cover was lifting and with it would come something Berlin had learned to fear more than enemy tanks. Berlin himself was a man of precision.

At 45 years old, he represented everything the Vermach valued in its officers. Knights cross with oak leaves and swords. Chief of staff to Raml in North Africa. 3 years of Eastern Front experience. He had survived Poland, France, Russia, and North Africa by understanding one principle. Anticipate the enemy’s advantage, then neutralize it through superior positioning and movement.

But in July 1944, that principle had become impossible to execute. Panzer division committed to Normandy as an armored reserve had spent the past month being disintegrated in place. Every attack bogged down, every maneuver interrupted, every position eventually overrun by an enemy with resources that seemed literally infinite.

The division that had left Chartres on June 7th with 316 tanks now had 93 operational. The fuel trucks that had carried 350,000 L of gasoline were running dry. The ammunition trains were depleted. The repair shops had ceased effective operations due to lack of spare parts and the men, the professional soldiers who had made Panzer the showcase division of the Wermacht were being ground away by continuous Allied pressure.

But now, finally, there was a chance. Operation Cobra was launching today. American forces contained and compressed into their Normandy beach head for nearly 8 weeks were breaking out. The plan was to seal the breakthrough with a coordinated Panzer counterattack. Elements of Panzer Lair would strike the American right flank supported by Dasich division and other German reserves.

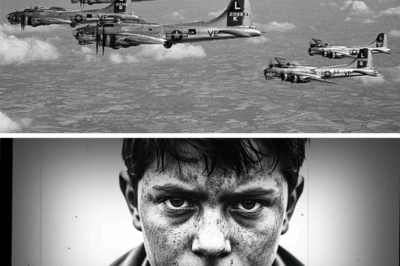

If timed correctly, if executed with precision, the attack might drive deep into the American spearhead and disrupt the entire breakout. It was a possibility that Bolerine, despite everything he had seen, still allowed himself to believe in. At 8:30 hours, the Jabos began arriving. The American fighter bombers, P47 Thunderbolts, rolled in from the west in waves that didn’t diminish or pause.

four aircraft, then eight more, then 20, then formations too large to count. Each P47 carried eight 127 mm rockets, and up to 2,500 lb of bombs under the fuselage. The aircraft descended in attack dives, engines screaming, rockets firing in rippling salvos that created concussion waves visible from kilometers away. The ground beneath the German positions heaved and buckled with each impact.

Trees were uprooted. Hedge that had stood for centuries vaporized in seconds. The dust and smoke rose in a column 3,000 m high. The earth itself seemed to writhe and convulse under the relentless assault from above. Bier lines radio operators were screaming reports into their headsets. The forward battalions were being annihilated.

Panthers were being flipped onto their backs by near miss explosions. Infantry and foxholes were dying from concussion alone. Blast waves rupturing internal organs from explosions landing 50 meters away. Command posts were being obliterated. Supply vehicles disintegrated into wreckage. Hospital tents were buried under cascades of earth and debris.

One radio operator, his voice cracking with static and panic. Sir, first battalion reports all officers down. Approximately 27 Panthers destroyed or disabled. Survivors taking shelter in hedgerros. Ammunition trucks burning. Fuel depot completely destroyed. Ground craters 5 meters deep, blocking all vehicle movement. Request immediate air support.

Another voice. Different operator. Sir, second battalion command post is buried. Casualties estimated at 80%. Approximately 40 Panthers confirmed destroyed in forward positions. Only three tanks can still move under their own power. Berlin listened to these pleasing there would be no air support. There were no German fighters left.

The Luftwaffer had abandoned Normandy weeks ago. He knew this with absolute certainty because he had watched the skies for the past month and seen them empty of German aircraft. Where once the fighters had appeared, now there was only silence and the thunder of enemy engines. Communication lines severed. One Panzer Grenadier Regiment, 200 soldiers before the bombing started, reported only 16 men fit to carry weapons when the first wave ended.

A third of the division’s support vehicles had simply ceased to exist. Medical teams had been buried in their aid stations. Mechanics were dead at their repair benches. Ammunition depots had detonated in catastrophic explosions that created fireballs visible for kilome. The divisional fuel storage was a burning lake of gasoline.

Bioline listened to these reports with terrible clarity. He understood what was happening. His division was being systematically destroyed. Not defeated through superior tactics. Not overwhelmed by trained infantry assault, but annihilated from above by an enemy he could not reach, could not retaliate against, could not even clearly see.

The bombers operated from 30,000 ft. His anti-aircraft guns fired at targets barely visible through the smoke and dust. Occasional aircraft were damaged. None were brought down. The bombing simply continued, wave after wave, relentless and without mercy. Each wave lasted approximately 8 minutes, 30 seconds of bombing silence.

Then the next wave arrived. The cycle repeated itself, mechanical and remorseless. At 1100 hours, a break in the bombing, 20 minutes of silence, which for Biolin meant he could finally assess the damage. He sent runners forward to find out what remained of his division. What they reported was beyond catastrophe. The forward battalion, 900 men with 14 Panthers and 32 halftracks, had ceased to exist as a coherent unit.

70% casualties. The survivors were wandering in a state of shock, unable to form any organized defense. A runner staggered back, covered in ash and blood. Signal corbs equipment obliterated. Supply convoy completely disintegrated. Second battalion reports operational strength of 300 men from 900.

The command post bunker partially collapsed. We have 13 minutes of water and no food. The tanks in the forward positions, all destroyed. At least 40 panthers confirmed destroyed. The divisional repair shops have been completely obliterated. We cannot rebuild. We cannot replace. Every tank in the forward positions had been destroyed or immobilized.

The battalion commander was dead, buried in his command bunker when a bomb collapsed the structure directly on top of him. Signal cores engineers had died trying to restore communication lines that would be severed again within minutes. The division’s workshop areas had been transformed into scrap metal and human remains.

The ammunition magazines were craters filled with twisted steel and ash. As Berlin was trying to process this information, the bombing resumed. This time it was B7 flying fortresses, heavy bombers conducting their own strikes on German rear positions. Each B17 carried 2,500 kg of ordinance. 371 heavy bombers dropped their loads over a 17.5 square km area in 90 minutes.

The tonnage equaled 240 kg of explosives per square meter. The American bombarders weren’t targeting specific units or positions. They were targeting everything. The landscape itself was being transformed into a cratered wasteland. What Berlin could not see from his command post, but what he understood from the relentless waves overhead was that the Luftwafa had abandoned Normandy.

For 90 minutes, not a single German fighter appeared. The sky belonged entirely to the Americans. In that moment, he realized the mathematics of air supremacy made tactical brilliance irrelevant. There was no counter to this. There was only annihilation. No strategy could address what was happening. No positioning, no maneuver, no counteroffensive could stop waves of bombers coming from 30,000 ft where German rifles could not reach and German pride could not defend.

At 1400 hours, the bombing finally stopped, complete silence. For 90 minutes, there had been continuous explosions. Now there was only the sound of dying soldiers, burning vehicles, the wind moving through the rubble, and the distant roar of American engines. As Seventh Corps prepared to attack, Bioline climbed into his command halftrack and tried again to contact his forward units.

This time he received responses, but the responses were almost worse than silence. Estimated total division casualties, 2,500. Estimated operational tanks, seven. Seven Panthers scattered across 8 km of front. The division that had started Operation Cobra with 93 tanks now had seven. The Americans attacked at 1400 hours immediately after the bombing stopped.

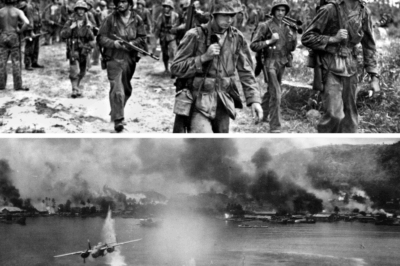

The attack had been planned to begin at 9:30 hours, but the bombing had continued longer than expected. The attack plan was simple. Seventh Corps, three infantry divisions, and two armored divisions pushing south through ground. so cratered that vehicular movement was nearly impossible. But where the German defensive line had been so thoroughly shattered that organized resistance barely existed.

What had been a prepared defensive position was now a lunar landscape. Craters 20 m across and 5 m deep pocked the terrain. Trees were gone. Hedros had vanished. The soil itself had been violently churned. Berlin’s remaining Panthers engaged the American spearhead. The Panthers were tactically superior to the Sherman tanks that comprised the majority of the American armored force.

The Panthers 75mm gun could penetrate a Sherman’s frontal armor at 2,200 m. The Sherman’s 75 mm gun required the range to drop to 500 m to achieve a penetration on the Panther’s frontal slope. But tactical superiority in gun performance meant nothing when your tanks were immobilized, when your ammunition was depleted, when your fuel was running dry, and when waves of American fighter bombers were still arriving to attack any German position they could locate.

Boline watched from his command post as the American infantry advanced through the cratered landscape. They moved with professional discipline, using the bomb craters for cover, advancing in small groups, supporting each other with overlapping fields of fire. They were not always elite American units.

Some of them were green replacements, their uniforms still pristine, faces showing the shock of combat. But they were moving forward because behind them was armor. Behind that armor were more infantry. Behind all of that was more armor. And behind all of that was an industrial system that could produce more men, more tanks, more everything than Germany could destroy in a month of constant combat.

What resistance there was came from fragments of German divisions, men and vehicles scattered across the battlefield by the bombing. Trying to organize some form of coherent defense, Berlin committed his remaining Panthers to counterattack the American spearhead. The Panthers engaged at maximum effective range, 1,700 m, and destroyed several American Shermans.

But there were more Shermans, always more Shermans. For every Sherman that burned, another column advanced behind it. The American supply system was feeding replacements faster than Panzer could destroy them. By nightfall on July 25th, the American breakthrough was complete. The 7th Corps had advanced 5 km through the shattered German defenses.

It wasn’t a spectacular breakthrough by the standards of mobile warfare. But the German line, such as it existed, had been broken, and once broken, it could not be repaired. The mathematics of destruction told the story with brutal clarity. For Berlin, watching his seven remaining Panthers engage waves of American armor through the smoke and dust, the numbers revealed a simple and terrible truth.

Germany had produced approximately 6,000 Panther tanks total throughout the entire war. In July 1944 alone, American factories were producing 4,500 Shermans per month. Every Sherman destroyed was replaced within weeks by a newly produced tank rolling off assembly lines in Detroit, Chrysler, American Locomotive, and Baldwin locomotive works.

Every Panther lost was irreplaceable. The production lines that had created Panzer were being systematically destroyed by Allied bombing. By autumn 1944, some assembly lines were forced to close entirely due to lack of materials and workers drafted for military service. Panzer division lost an average of seven tanks per day during its deployment in Normandy.

At that rate, the total German Panther production would be consumed in less than 9 months of continuous combat. But there would be no continuous combat. By August 1st, Panza leer division was officially withdrawn from frontline combat, rendered incapable of organized offensive action. The division’s vehicles were cannibalized for parts.

The surviving men were scattered to other units as replacements. Of the 5,000 soldiers who had begun the Normandy campaign on June 7th, approximately 2,500 remained operational. Of the 316 tanks that had left Chartra, zero remained combat capable. The division was technically reconstituted, receiving new equipment and fresh conscript replacements, but it was never again an elite formation.

The replacement tanks came without the armorplate upgrades of the original Panthers. The replacement crews had been trained in six-week programs instead of the six-month courses that had created the original division’s expertise. The replacement soldiers were conscripts, not the professional volunteers who had made the division formidable.

Panzer would continue to exist on paper until the end of the war. But the elite demonstration division that had departed Chartra on June 7th, 1944 had ceased to exist on July 25th. Bierline understood this in that moment as the bombing continued and his division disintegrated around him. Not in retrospective interviews or postwar memoirs, but in the raw and immediate experience of watching an entire elite unit annihilated by an enemy he could not see, could not fight, and could not defeat. This was not something he would

understand later. This was something he understood now. In the dust and smoke of his destroyed command post, the knowledge became crystalline and absolute. In the silence that followed the bombing, crouched in the rubble of his command post at 1400 hours on July 25th, 1944, Bioline understood the fundamental truth of modern industrial war.

Tactical excellence, training, courage, and superior positioning mean nothing against a system that can afford to destroy the same ground 100 times if necessary. You cannot defeat that kind of system with tactics. You can only lose to it more slowly. The 4,200 tons of bombs dropped on his division in 90 minutes represented something beyond military calculation.

It represented the productive capacity of a nation that could afford devastating losses and simply produce more. America could build 100 factories for every factory Germany possessed. America could train 1,000 pilots for every pilot Germany could train. America could refine 1 million barrels of oil per day, while Germany refined 100,000.

This was not a military problem. This was not a tactical problem. This was a problem of systems. systems so vast, so coordinated, so overwhelmingly productive that no amount of German skill or bravery could compensate. The war was not lost at Operation Cobra. It was lost in factories in Michigan and Ohio and Pennsylvania.

It was lost in oil refineries in Texas. It was lost in the arithmetic of production before the first bomb fell on Normandy. It was lost months ago, perhaps years ago, when American production capacity began its inexurable climb and German capacity could not keep pace. At that moment, with seven tanks remaining, 2500 men dead or dying, his division in ruins, his command post half destroyed, Bolan knew with absolute certainty, there was no strategy that could overcome this.

There was no tactical brilliance that could compensate. There was no number of elite soldiers or superior tank designs that could counter what was happening. There was only the slow mathematical certainty of defeat by a nation that could afford to rebuild faster than Germany could destroy. The German officer corps could plan, could maneuver, could fight with skill and bravery.

But none of that mattered against industrial arithmetic. Modern war is won not in the moment of battle, but in the factories and trainingmies and oil fields of the victor’s homeland, long before the first shot is fired. This was the lesson of Operation Cobra. This was the moment Berlin truly understood it. Not after the war, not in reflection, not in memory, in that present moment as his division died. He understood it completely and irrevocably.

News

CH2 One Of Many Unsung Heroes – The 13-Year-Old Boy Who Guided Allied Bombers to Target Using Only a Flashlight on a Rooftop

One Of Many Unsung Heroes – The 13-Year-Old Boy Who Guided Allied Bombers to Target Using Only a Flashlight on…

CH2 June 4, 1942 At 10:30 AM: The Five Minutes That Destroyed Japan’s Chance Of Winning WW2

June 4, 1942 At 10:30 AM: The Five Minutes That Destroyed Japan’s Chance Of Winning WW2 June 4th, 1942,…

CH2 The Moment That Almost Changed History: Why Patton Wanted to Attack the Soviets in 1945 Revealed – The Warning Eisenhower Refused to Hear

The Moment That Almost Changed History: Why Patton Wanted to Attack the Soviets in 1945 Revealed – The Warning Eisenhower…

CH2 German Mockery Ended — When Texas Oilmen Fueled The Army Hitler Couldn’t Stop

German Mockery Ended — When Texas Oilmen Fueled The Army Hitler Couldn’t Stop August 12th, 1944, outside the Normandy…

CH2 The Decision That Saved 100,000 Lives On One Of The Most Brutal Campaign in WW2 — The Bypass of Rabaul

The Decision That Saved 100,000 Lives On One Of The Most Brutal Campaign in WW2 — The Miracle Happened in…

CH2 When Hitler Made A Fatal Mistake: The Moment The World Knows Of The Fall Of The Third Reich

When Hitler Made A Fatal Mistake: The Moment The World Knows Of The Fall Of The Third Reich The…

End of content

No more pages to load