June 4, 1942 At 10:30 AM: The Five Minutes That Destroyed Japan’s Chance Of Winning WW2

June 4th, 1942, 10:24 a.m., some 240 nautical miles northwest of Midway Atoll, Lieutenant Commander Wade McClusky peered down through the canopy of his SBD Dauntless, heart pounding, as the ocean below revealed a scene that should have been impossible. Four Japanese aircraft carriers—Akagi, Kaga, Sōryū, and Hiryū—glided across the waves in a tight diamond formation, their decks swarming with aircraft being prepared for launch. Bombs were being armed, fuel lines snaked across the wood planking, ordinance carts clattered beside waiting bombers. From the air, it was a perfect target, a trap set by circumstance and fortune that the Japanese could neither see nor anticipate. Every plane, every crew, every carefully rehearsed procedure made these carriers extraordinarily vulnerable, and yet McClusky had spent the past two hours scanning empty ocean, his fuel gauges ticking downward, watching as thirty-two dive bombers from Enterprise and Hornet followed him toward what seemed certain failure.

Earlier that morning, McClusky had made a decision that would define his career and alter the course of the Pacific War. His torpedo squadrons had already suffered catastrophic losses. Torpedo Squadron Eight had been annihilated, fifteen planes reduced to flaming wreckage on the ocean surface, leaving only one survivor to drift among the waves. American attacks had seemed hopeless. The dive bombers pressing their assaults from the decks of Enterprise and Hornet had struggled with coordination, lacking fighter escort, often arriving piecemeal at the Japanese fleet. Yet McClusky had refused to turn back when the ocean appeared empty. Instead, he noticed a lone Japanese destroyer, Arashi, racing northeast at full speed. The ship had been depth-charging the American submarine Nautilus moments earlier and was now returning to the main fleet. McClusky made the intuitive leap to follow the destroyer’s wake, trusting instinct over expectation, and now, as he pushed his plane into a 70-degree dive, the potential for five minutes of devastating violence stretched out beneath him.

Below, the Japanese had no radar, no awareness of the approaching American dive bombers. Their combat air patrol, deployed to sea level, had just finished annihilating the torpedo squadrons, leaving the sky above the carriers unguarded. It was a gap that McClusky and his squadron would exploit with deadly precision. Thirty-one more dive bombers followed his lead, rolling into the dive, engines screaming, bombs clutched beneath the fuselage. Seconds became eternity as they hurtled toward the decks below, the concentrated potential for destruction focused on four floating fortresses. At 10:24 a.m., those five minutes began—the moment Admiral Chester Nimitz would later describe as decisive for the fate of the Pacific Fleet.

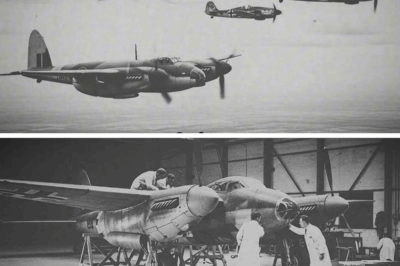

To fully grasp the weight of those five minutes, it’s necessary to understand the mindset of the Japanese Empire in early 1942. Since December 7th, 1941, the Japanese military had expanded across a region larger than Europe, conquering Hong Kong in eighteen days, Manila in twenty-six, and Singapore in seventy. They had driven the British from Malaya, the Dutch from Indonesia, and forced the Americans from the Philippines. The Kido Butai, Japan’s carrier striking force, had yet to suffer a defeat, having destroyed five battleships at Pearl Harbor, raided Darwin, Australia, and chased the British Eastern Fleet from the Indian Ocean. Japanese pilots were veterans of combat in China since 1937, their Mitsubishi Zero fighters outperforming every Allied fighter in the Pacific. Torpedo bombers and dive bombers had proven devastating against every target they had encountered. The Japanese military doctrine emphasized offense, aggression, and the invincibility of spirit, encapsulated in the concept of Yamato Damashi—the spirit of Japan—meant to overcome material disadvantages through courage, skill, and sacrifice.

Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, commander of the Combined Fleet, had orchestrated the Midway operation with meticulous attention to detail. He designed the plan to lure the American carriers into a decisive battle while simultaneously capturing Midway Atoll, completing what Pearl Harbor had begun. Over two hundred ships—including four fleet carriers, two light carriers, eleven battleships, sixteen cruisers, forty-six destroyers, and fifteen submarines—had been assembled for the operation. The carriers alone carried 248 of the most experienced naval aviators in the world. The battleship Yamato, flagship of the Combined Fleet, displaced 72,000 tons and mounted nine 18-inch guns, the largest naval rifles ever built. Against this formidable armada, the Americans could muster only three carriers, eight cruisers, and fifteen destroyers. Yorktown, recently patched together in a remarkable three-day effort after being damaged at the Battle of the Coral Sea, represented the thin thread upon which American hopes hung. Yet they had an advantage Japan did not suspect: intelligence.

Commander Joseph Rochefort and his team at Station Hypo in Pearl Harbor had cracked the Japanese naval code, revealing not just the date and location of the impending Midway strike, but the composition of the fleet and the approach route. Nimitz, acting on this intelligence, positioned his carriers northeast of Midway, concealed from view, ready to strike at the perfect moment. Yet knowledge of the enemy’s location did not make victory assured. The morning attacks had been brutal and nearly catastrophic. Marine fighters from Midway had been shot down by Zeros; Army B-17s bombing from high altitude had scored no hits; Marine dive bombers had been decimated in piecemeal attacks. The torpedo squadrons, especially the ill-fated Torpedo Eight, had been destroyed entirely. Only Ensign George Gay survived the assault, adrift in the Pacific, witnessing the unfolding disaster. Out of forty-one torpedo bombers sent against the Japanese carriers, only six returned to their ships. Not one had landed a torpedo.

But these near-suicidal attacks, though ineffective in immediate terms, set the stage for what was about to unfold. Japanese pilots, intent on annihilating American attackers, had committed their fighters to low-altitude defense, leaving the skies above their carriers entirely unguarded. At 10:20 a.m., Admiral Chuichi Nagumo aboard Akagi issued the order to launch a counterstrike against the American carriers, unaware that the threat from above was imminent, unseen, and about to strike with devastating precision. The American dive bombers, led by McClusky, were poised to exploit a flaw that the Japanese command had overlooked: in focusing on immediate threats, they had left themselves open to a decisive strike.

The carriers, symbols of Japanese naval might and technological superiority, were now at their most vulnerable state. The meticulous planning of Yamamoto, the disciplined drills of the carrier air groups, the experience and skill of the pilots—all had converged to create a perfect target. McClusky’s dive bombers, arriving from the sky with near-perfect timing, would descend upon these floating fortresses with gravity and inevitability. It was a convergence of human decision, intelligence, luck, and timing that would crystallize in the next five minutes.

At the heart of it, what was about to occur underscores a fundamental truth of naval warfare: preparation, intelligence, and bold, decisive action can overcome numerical and technological inferiority. The Japanese carriers, though formidable, were caught in a moment of exposure, and the Americans, though battered, outnumbered in every conventional metric, were positioned to strike. McClusky, with thirty-one dive bombers following him, rolled into his dive, engines screaming, bombs primed, and eyes fixed on the decks below. The fate of the Pacific, of the Japanese navy, and indeed the trajectory of World War II, hinged on the precise alignment of strategy and opportunity.

The Pacific remained an immense expanse of unpredictable weather, shifting tides, and mortal danger. Each dive bomber carried not just ordnance but the concentrated hopes of a beleaguered American fleet, and every second in the air was a confrontation with chance. The Japanese carriers had ruled the waves since December, their pilots skilled, their machines superior in many respects, their doctrine emphasizing decisive, aggressive action. Yet, in this fleeting moment, chance and intelligence had aligned with audacity. The next five minutes, starting at 10:24 a.m., would determine the limits of Japanese power, test the courage of American aviators, and set in motion a chain of events that no commander could have fully anticipated.

Above, McClusky maintained control, navigating the dive, coordinating his squadron, and keeping his eye on the precise release points, all while aware that every second lost increased risk. Below, the Japanese fleet remained oblivious to the threat, their eyes focused on torpedo bombers that had already been dealt with, their aircraft on deck immobile, their pilots unprepared. For the first time in months, the balance of initiative had swung precariously toward the Americans. The moment of vulnerability had arrived, and with it, the possibility of a strike that would reverberate through history.

The carriers were positioned in such a way that a single, coordinated strike could decimate their aircraft, ignite fires across fuel-laden decks, and fundamentally alter the Pacific theater’s balance. McClusky’s calculations, honed by experience, training, and intuition, had placed him and his squadron in precisely the right position to deliver that strike. The dive was not just a maneuver—it was a culmination of strategy, persistence, and courage. The Pacific Ocean, wide and indifferent, now framed a confrontation that could reshape the war. Every man in the dive bombers, from the pilots to the bombardiers, was acutely aware that the next five minutes would determine more than just their immediate survival; it would decide the fate of nations, fleets, and thousands of lives.

And so, at 10:24 a.m., Lieutenant Commander McClusky and his dive bombers pressed over the edge of the horizon, plummeting toward destiny. The Japanese carriers, symbols of invincibility, were about to learn that vulnerability could arrive even to the most meticulously prepared. The scene was set, the actors in place, and the stage was the vast Pacific. The consequences of the coming minutes would be enormous, but in the sky above Midway, the dive had begun, and the story of those five minutes—the turning point of the Pacific War—was about to unfold.

Continue below

June 4th, 1942, 10:24 a.m. Pacific Ocean, 240 nautical miles northwest of Midway Atoll. Lieutenant Commander Wade McClusky looked down from 14,000 ft and saw what should have been impossible. Four Japanese aircraft carriers steamed below him in perfect diamond formation. Their flight decks were packed with armed aircraft, fuel lines snaking across wood planking, ordinance carts positioned beside waiting bombers. Every plane was being prepared for launch.

The carriers were at their most vulnerable state possible. This was not supposed to happen. McCluskey had spent the past 2 hours searching empty ocean, his fuel gauges dropping toward zero, 32 dive bombers following him toward what seemed like certain failure. The Japanese fleet was not where intelligence had predicted. His squadrons from Enterprise and Hornet had become separated.

Torpedo squadron eight had already been annihilated. Every plane shot down. Only one man surviving. The American attack was falling apart. But McClusky had made a decision 30 minutes earlier that would change the course of the Pacific War. When he reached the expected intercept point and found nothing but empty water, he did not turn back.

Instead, he spotted a lone Japanese destroyer racing northeast at full speed. The destroyer Arashi had been depth charging the submarine Nautilus and was now rejoining the main fleet. McCluskey made an intuitive leap. He followed the destroyer’s wake. Now, as he pushed over into his dive, McClusky was about to deliver a blow that would destroy Japanese naval supremacy in 5 minutes of devastating violence.

The Japanese had no idea American dive bombers were overhead. They had no radar. Their combat air patrol of zero fighters was down at sea level, having just finished slaughtering American torpedo bombers. The sky above the carriers was completely undefended.

What happened in the next 5 minutes would later be described by Admiral Chester Nimttz as the moment that decided the fate of the Pacific Fleet and the forces at Midway. It was 10:24 a.m. when Lieutenant Commander McClusky rolled his SBD Dauntless into a 70° dive. 31 more dive bombers followed him down. The Japanese lookout screamed their warning seconds too late.

To understand why these five minutes mattered so profoundly, you must understand what Japan believed about itself and what it had accomplished in the 6 months since Pearl Harbor. The Japanese Empire in early 1942 considered itself invincible. The statistics seemed to prove it. Since December 7th, 1941, Japanese forces had conquered an area larger than Europe. They had taken Hong Kong in 18 days, Manila in 26 days, Singapore in 70 days.

They had driven the British from Malaya, the Dutch from Indonesia, the Americans from the Philippines, the Kido Bhutai, the Japanese carrier striking force, had never been defeated. It had sunk five battleships at Pearl Harbor. It had raided Darwin, Australia.

It had driven the British eastern fleet from the Indian Ocean, sinking the carrier Hermes and two cruisers. Everywhere the Japanese carriers went, they brought destruction. Their pilots were the most experienced in the world. Veterans of combat in China since 1937. Their Mitsubishi Zero fighters outperformed every Allied fighter in the Pacific.

Their torpedo bombers and dive bombers had proven devastating against every target. Japanese naval doctrine emphasized the offensive spirit, the supremacy of attack, the inevitability of victory through superior training and fighting spirit. The concept of Yamato Damashi, the spirit of Japan, was supposed to overcome any material disadvantage.

Japanese officers believed their forces were simply better than the Americans, better trained, more experienced, more dedicated, willing to die for the emperor. Admiral Izuroku Yamamoto, commander of the combined fleet, had designed the midway operation to finish what Pearl Harbor had started.

The plan was elegant in its ambition. A diversionary attack on the Illusian Islands would draw American attention north. Then the main force, the most powerful fleet Japan had ever assembled, would strike midway and lure the American carriers into a decisive battle. The Japanese would crush them with overwhelming force. The numbers seemed overwhelming.

Yamamoto had assembled over 200 ships for the midway operation. Four fleet carriers, two light carriers, 11 battleships, 16 cruisers, 46 destroyers, 15 submarines. The carriers are Kagi, Kaga, Soru, and Hiu carried 248 aircraft. The most experienced naval aviators in the world.

The battleship Yamato, flagship of the combined fleet, displaced 72,000 tons and carried nine 18in guns, the largest naval rifles ever built. Against this armada, the Americans could muster three carriers, eight cruisers, 15 destroyers. The carrier Yorktown had been damaged at Coral Sea and should have required 3 months of repair.

Pearl Harbor Navy Yard mechanics had patched her in just three days, good enough for one more battle. The American force was outnumbered in every category except one. They knew the Japanese were coming. Commander Joseph Roshapor and his team of codebreakers at station Hypo in Pearl Harbor had cracked the Japanese naval code. They knew the target was Midway. They knew the date was June 4th.

They knew the composition of the Japanese force and their approach route. Admiral Nimitz had positioned his carriers northeast of Midway, hidden and waiting. But knowing the enemy was coming did not guarantee victory. The American attacks on the morning of June 4th had been disastrous. Marine fighters from Midway had been slaughtered by Zeros.

Army B17 bombers attacking from high altitude scored no hits. Marine dive bombers pressing home their attacks were the five Dam shot down in flames. Torpedo bombers from all three American carriers attacked separately without fighter escort without coordination. Torpedo squadron eight from Hornet. All 15 planes were destroyed.

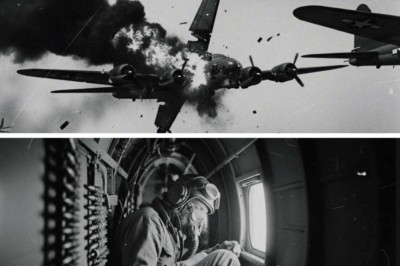

Only Enen George Gay survived floating in the Pacific watching the battle rage around him. Of 41 American torpedo bombers that attacked the Japanese carriers, only six returned to their ships. Not one scored a torpedo hit. The attacks seemed suicidal and futile. Japanese Zero fighters dove from above, their 20 mm cannon ripping apart the slow, obsolete TBD Devastators. Anti-aircraft fire filled the sky with black bursts.

American torpedoes plagued by defects, ran under their targets, or failed to explode. On the bridge of the carrier Akagi, Commander Mitsuo Fuida watched the American attacks with contempt mixed with respect. Fuida had led the Pearl Harbor attack. He had commanded the air group that destroyed battleship Row. He understood combat aviation as well as any man alive.

The courage of the American torpedo bomber crews impressed him. But their attacks had been futile. Not one carrier was damaged. The Americans were throwing away their planes and crews for nothing. What Fuida did not realize was that those suicidal torpedo attacks had accomplished something crucial. They had pulled the Japanese combat air patrol down to sea level.

Dozens of Zero fighters swarmed low over the water, finishing off the last American torpedo bombers. Every Japanese fighter was down low, their pilots focused on the immediate threat. No one was watching the sky above. At 10:20 a.m. on Akagi, Admiral Chuichi Nagumo gave the order to launch the counter strike against the American carriers.

Japanese scouts had finally located the American fleet. Nagumo would destroy them. On Akagi’s flight deck, 36 aircraft sat in launch position, engines warming, dive bombers and torpedo bombers, all armed and fueled, ready to devastate the American carriers. On Kaga, 30 planes waited. On Soryu, another 21.

The Japanese counter strike force totaled 87 aircraft, enough to sink every American carrier. Admiral Nagumo was confident. His carriers had just repelled massive attacks. His pilots had shot down dozens of American planes. Now it was time to strike back. The big carriers began turning into the wind.

Within 5 minutes, all planes would be launched. The destruction of the American carrier force would begin. Then the dive bombers arrived. Lieutenant Commander McClusky’s radio call was simple. Attack. He rolled into his dive at 10:24 a.m. Behind him, 31 more Dauntless dive bombers pushed over.

They fell from 14,000 ft at 260 mph, howling down at 70° angles. The Japanese had no time to react. The anti-aircraft guns that had devastated the low-flying torpedo bombers could not elevate fast enough to track the dive bombers. The Zero fighters were miles away and thousands of feet too low. The Japanese carriers, having just turned into the wind for launch operations, could not maneuver. They were perfect targets.

At 2,500 ft, the pilots released their bombs. 500lb armor-piercing bombs with delayed fuses designed to penetrate a ship’s deck before exploding. The bombs fell for 4 seconds before impact. Those 4 seconds decided the war. The first bomb hit Kaga at 10:25 a.m. It struck just after of the island superstructure.

The explosion detonated aviation fuel and armed bombs on the flight deck. A second bomb hit near the forward elevator. A third hit the port side. A fourth struck the bridge, killing Captain Jaku Okada and most of the senior officers. Within 60 seconds, Kaga was transformed from a powerful warship into a funeral p.

Simultaneously, three planes from Lieutenant Richard Best’s section dove on a Kagi. The formation had been confused. Almost all the dive bombers had attacked Kager. Best pulled his two wingmen out of their dives and headed for the second carrier. His bomb hit Akagi precisely amid ships, penetrating the flight deck and exploding in the hanger deck.

The shockwave detonated torpedoes and bombs stored there. Secondary explosions ripped through the ship. Commander Fuida, standing on a kagi’s bridge, heard the scream of the dive bombers seconds before impact. He looked up to see three black aircraft plummeting toward his ship. A terrible silence hung over the ship for an instant. Then the first bomb hit.

The explosion lifted him off his feet. Smoke and flame erupted from the hanger deck. He watched in horror as Kaga and Soru also erupted in flames. Three carriers burning simultaneously. The scene was, in his words, horrible to behold. The third carrier, Soru, was attacked by dive bombers from Yorktown. Lieutenant Commander Max Leslie led 17 planes in a perfectly executed attack.

Three bombs hit Soryu in quick succession. The first hit near the forward elevator, the second amid ships, the third aft. Aviation fuel ignited. Bombs and torpedoes exploded. Within minutes, Soryu was a blazing wreck. Her crew abandoning ship. The attack lasted 5 minutes. When it was over, three Japanese fleet carriers were mortally wounded.

Akagi, flagship of the carrier striking force, was burning out of control. Kaga, veteran of Pearl Harbor and every major Japanese operation, was consumed by explosions. Soryu, the smallest of the fleet carriers, was engulfed in flames. More than 240 aircraft were destroyed, either burned on the flight decks or trapped in the hangar decks below.

Over 700 highly trained pilots and air crew were dead or would die in the fires. The statistics of what had just been destroyed were staggering. These three carriers represented 2/3 of Japan’s fleet carrier force. They had participated in every major Japanese naval operation since Pearl Harbor. Akagi displaced 36,000 tons and could carry 91 aircraft.

Kaga displaced 38,000 tons and carried 90 aircraft. Soryu displaced 18,000 tons and carried 71 aircraft. Together, they had been the core of Japanese naval air power. The pilots and air crew lost in those 5 minutes could not be replaced. Japan had trained these men for years. They had combat experience stretching back to the China War in 1937.

The torpedo bomber pilots could put their weapons within feet of their target. The dive bomber pilots could hit moving ships from 12,000 ft. The fighter pilots had destroyed Allied aircraft over China, Pearl Harbor, the Philippines, the Dutch East Indies, son. This was not just equipment burning.

This was institutional knowledge, accumulated skill, irreplaceable experience going up in flames. What made the disaster even worse was the timing. If the American attack had come 10 minutes earlier, many Japanese aircraft would still have been in the hanger decks where they were somewhat protected. If the attack had come 10 minutes later, most aircraft would have been launched and the carrier’s decks would have been relatively clear.

But the American dive bombers arrived at the worst possible moment. Every carrier had its deck packed with fully fueled, fully armed aircraft. The flight decks had become bomb magazines. Admiral Nagumo, shaken by the explosion, attempted to maintain command from Akagi’s bridge, but fires were spreading. Smoke filled the bridge. At 10:46 a.m., he abandoned ship, climbing down a rope to escape the flames. His staff followed. They transferred to the light cruiser Nagara. From there, Nagumo could only watch as his striking force burned. On Akagi, damage control parties fought desperately. Captain Tairo Aayoki remained on the bridge trying to regain control of his ship, but the fires could not be contained.

Explosions rocked the carrier as aviation fuel and ordinance detonated. The hanger deck became an inferno. Men trapped below decks died in the flames or jumped into the sea. The air officer looked back at Fuida and said they would not be able to stay on the bridge much longer.

Fuida, already injured from an appendectomy before the battle, could only watch as the carrier that had carried the attack to Pearl Harbor died. 267 men perished aboard a Kagi. Kaga’s fate was similar. The multiple bomb hits had created fires that raged out of control. The carrier’s damage control systems had been designed for single hits, not multiple simultaneous explosions. Water manes ruptured. Power failed.

Communications between decks were cut. Men fought fires with no water, no power, no coordination. The ship’s list increased as water flooded lower compartments. By afternoon, the order was given to abandoned ship. 81 men died aboard Kaga. Soryu suffered the fastest death.

Captain Ryusaku Yanagimoto refused to leave his ship. His executive officer and others begged him to abandon the burning carrier. He refused. He would go down with his ship. Soru’s hull was relatively thin compared to the larger carriers. The fires burned through bulkheads more quickly. The ship developed a severe list. At 7:13 p.m. on June 4th, Soryu rolled over and sank, taking Captain Yanjimoto and 71 crewmen with her, but one Japanese carrier remained.

Hiu had been several miles north of the other three carriers during the American attack. She escaped the devastation. Rear Admiral Tamon Yamaguchi commanding Hiyu immediately prepared a counter strike. At 10:50 a.m. while the other three carriers burned, Hiru launched 18 dive bombers escorted by six zeros. At 1:30 p.m., these aircraft found and attacked Yorktown, scoring three bomb hits that set her a fire and knocked out her boilers.

Hiu launched a second strike at 2:30 p.m. 18 torpedo bombers escorted by six zeros found Yorktown at 2:45 p.m. and scored two torpedo hits. The damage was catastrophic. Yorktown took on a severe list. At 300 p.m., Captain Elliot Buckmaster ordered abandoned ship.

The carrier that had been patched up in 72 hours that had contributed dive bombers to the strike that destroyed three Japanese carriers was now dead in the water. But American revenge was swift. Scout planes from Yorktown located Hiru. At 5:00 p.m., dive bombers from Enterprise attacked. 24 Dauntless bombers dove on the last Japanese carrier.

Four bombs hit Hiyu, two near the forward elevator, two amid ships. The bombs started fires that quickly spread. Aviation fuel ignited. The hanger deck became a mass of flames. By 6:30 p.m., Hiyu was burning out of control. Her flight deck a twisted mess of burning metal. Admiral Yamaguchi refused to leave his flagship.

He and Captain Tomoko Kaku stayed aboard the burning carrier, preferring death to the dishonor of survival after defeat. At 2:30 a.m. on June 5th, Hiyu was scuttled by torpedoes from Japanese destroyers. Yamaguchi and Kaku went down with their ship along with 392 officers and men. The scope of the Japanese defeat was almost incomprehensible. In one day of battle, Japan had lost four fleet carriers.

All four veterans of Pearl Harbor, Akagi, Kaga, Soryu, and Hiyu were gone. With them went 248 aircraft and approximately 3,000 men, including many of the Imperial Navy’s most experienced pilots and air crew. The striking force that had dominated the Pacific for 6 months, had been annihilated. The psychological impact was shattering.

Japanese naval officers had believed their training, their experience, their fighting spirit made them invincible. They had conquered half the Pacific in six months. They had never been defeated in a major fleet engagement. And now, in one morning, the core of their carrier force had been destroyed by a numerically inferior American fleet. Commander Fuida, recovering from his broken ankles aboard the destroyer that rescued him from a Kagi, understood immediately what had happened.

Japan had lost the war. Not the battle, but the war. The margin of naval air superiority that had enabled Japan’s conquests was gone. The experienced pilots who could not be replaced were dead. The carriers that required years to build were at the bottom of the Pacific. Japan would never recover from this single day of losses. The contrast with American losses was stark.

The United States lost one carrier, Yorktown, which was already damaged and should not have been in the battle. The destroyer Hammond was sunk by a Japanese submarine while conducting salvage operations on Yorktown. Total American aircraft losses were 147 planes. Total personnel losses were 307 men. The exchange ratio was catastrophic for Japan.

Four carriers for one, 248 aircraft for 147, approximately 3,000 men for 307. The real difference was industrial capacity. The United States could replace its losses. Japan could not. Yorktown was one of seven American carriers in commission. Two more, Essex and Independence, would be commissioned before the end of 1942.

By the end of 1943, the United States would commission 13 fleet carriers and nine light carriers. By the end of the war, the United States Navy operated over 100 carriers of all types, including fleet carriers, light carriers, and escort carriers. Japan could not match this production.

Japanese shipyards could build perhaps one carrier per year under ideal conditions. The industrial base was too small. The resources were limited. The skilled labor was insufficient. Japan had begun the war with six fleet carriers and four light carriers. After Midway, four of the fleet carriers were gone. The two fleet carriers damaged at Coral Sea. Shukaku and Zuikaku would not return to service for months.

Japan’s carrier force was crippled. The pilot losses were even more devastating. Japanese naval aviation training took years to produce combat ready pilots. The standards were extremely high. The washout rate was severe. Japan had perhaps 1,500 highly trained carrier pilots at the start of the war.

After midway, perhaps 1,000 remained, and the training pipeline could not produce replacements fast enough. By 1944, Japanese carrier air groups would be filled with minimally trained pilots flying obsolete aircraft against American pilots with hundreds of hours of training in the most advanced aircraft in the world. Admiral Yamamoto, commanding from the battleship Yamato, hundreds of miles away, received the news of the disaster in disbelief.

He had assembled over 100 ships for the Midway Operation, the most powerful fleet Japan had ever sent to battle. He had planned to annihilate the American carriers. Instead, his own carrier force had been destroyed. At 2:55 a.m. on June 5th, Yamamoto issued the order to abandon the Midway operation and withdraw.

The invasion fleet turned for home. The withdrawal was humiliating. The landing force that was supposed to occupy Midway never got close. The battleships that were supposed to bombard the island into submission never fired a shot. The submarines that were supposed to intercept the American carriers were out of position.

The diversionary attack on the illutions accomplished nothing except the occupation of two baron islands that Japan would abandon a year later. American forces pursued the retreating Japanese fleet. On June 6th, dive bombers from Enterprise and Hornet found the heavy cruisers Moami and Mikuma. Both ships had collided during the chaotic night withdrawal. Mikuma was slowed to 12 knots.

The American dive bombers attacked repeatedly. Mikuma was hit by five bombs and sank that afternoon. Mogami was heavily damaged but survived. The cruiser would spend a year under repair. The Battle of Midway was over. The strategic consequences were immediate and permanent. Japan had lost the strategic initiative. The conquests were finished.

From June 4th, 1942 onward, Japan would be on the defensive. The Americans would choose where and when to attack. The Japanese would react, always with insufficient forces, always struggling to concentrate their remaining carrier air power. 2 months after midway, American forces landed on Guadal Canal. This began a campaign that would last 6 months and drain Japanese air power even further.

The carriers Shukaku and Zuikaku participated in the battles around Guadal Canal. Both survived, but their air groups were decimated. By the end of the Guadal Canal campaign, Japan had lost hundreds more pilots and aircraft. The training pipeline could not keep up. By mid 1943, Japanese carrier air groups were shadows of their former selves. The decline was relentless.

At the Battle of the Philippine Sea in June 1944, Japanese carrier aircraft attacked the American fleet in what American pilots called the Great Mariana’s Turkey Shoot. Over 300 Japanese aircraft were shot down in a single day. The pilots flying these missions had minimal training, minimal experience. They flew into concentrated anti-aircraft fire and were intercepted by American fighters directed by radar.

The slaughter was comprehensive. By October 1944, when the Japanese carrier force made its final appearance at the Battle of Lady Gulf, the carriers were empty shells. They carried few aircraft and had no experienced pilots to fly them. The carriers were used as decoys, sailing north to draw American attention while Japanese battleships attempted to attack the invasion beaches. The decoy worked.

Admiral William Holsey took the bait and chased the Japanese carriers north, but American escort carriers and destroyers stopped the Japanese battleships. The carriers that had been decoys were sunk by American air strikes. It made no difference. They had no aircraft to launch.

The path from Midway to Japanese defeat was clear and inevitable. Without carrier air superiority, Japan could not defend its conquered territories. Without the territories, Japan could not access the resources, especially oil, that sustained its war machine. Without resources, industrial production declined.

Without industrial production, the military could not replace losses. The spiral was irreversible. Lieutenant Commander McClusky’s decision to continue the search when his fuel was running low to follow the destroyer Arashi’s wake to attack at precisely the moment when the Japanese carriers were most vulnerable had set this spiral in motion.

Admiral Nimttz later stated that McClusky’s judgment decided the fate of the carrier task force and the forces at Midway. Without that decision, without the 5 minutes of devastation at 10:24 a.m. on June 4th, the Pacific War might have lasted years longer. The Japanese officers who survived midway, understood what had been lost. Captain Fuida would later write that the battle doomed Japan.

Vice Admiral Chuichi Nagumo, who commanded the carrier striking force, would later be relieved of command and sent to a backwater post. He committed suicide in July 1944 during the battle for Saipan rather than face capture. Rear Admiral Tamon Yamaguchi who went down with Hiyu was considered one of the most brilliant officers in the Imperial Navy.

His death deprived Japan of a leader who might have salvaged something from the disasters that followed. For the American pilots who participated in the battle, the victory was bittersweet. Torpedo Squadron 8 had been annihilated. Only Enen George Gay survived from 15 crews. Torpedo Squadron 6 from Enterprise lost 10 of 14 aircraft.

Torpedo Squadron 3 from Yorktown lost 10 of 12. The dive bomber squadron suffered losses, too. Of the 115 American aircraft that attacked the Japanese carriers on June 4th, 54 were lost. The cost of victory had been high. But the pilots who survived knew they had accomplished something extraordinary. Lieutenant Commander McCluskey, wounded in the shoulder by Japanese fighters during his escape, made it back to Enterprise with less than 5 gallons of fuel remaining. Some pilots ran out of fuel and ditched in the ocean.

10 pilots from McClusky’s group were never found. But the survivors knew what they had achieved. They had destroyed the Japanese carrier striking force. They had turned the tide of the Pacific War. The timing of the attack, that 5-minute window when all the factors aligned, was both lucky and earned.

Lucky that McClusky spotted the destroyer Arashi. Lucky that the Japanese carriers were turning into the wind for launch operations at exactly the wrong moment. Lucky that the Japanese combat air patrol was down at sea level chasing torpedo bombers. But the luck was earned through McCclusk’s decision to continue the search.

Through the torpedo bomber crews who sacrificed themselves to draw Japanese fighters low, through the cryptographers who broke the Japanese code, through Admiral Nimttz who positioned his carriers northeast of Midway based on that intelligence. War correspondent Robert Sherod would later write that Midway was the most crucial battle of the Pacific War, more important than Guadal Canal, more important than Ewoima or Okinawa.

Midway decided who would control the Pacific. After June 4th, 1942, that question was settled. The United States would control the Pacific. Japan would fight a defensive war, losing battle after battle, island after island, until the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki forced surrender in August 1945.

The reverberations of those 5 minutes continued for years. In July 1945, as Japan prepared for the expected American invasion of the home islands, military planners calculated they could possibly repel one landing attempt. But without carrier air power, without naval superiority, without the resources to sustain a prolonged defense, defeat was certain.

The kamikazes of 1945, the suicide attacks that threw away pilots and aircraft in desperate attempts to sink American ships, were symptoms of Japan’s complete loss of naval aviation capability. The trained pilots were dead, killed at midway and in the battles that followed.

The desperate, barely trained pilots who replaced them, could do nothing but crash their planes into American ships. Admiral Yamamoto, who had planned the Midway operation, never recovered from the defeat. He continued to command the combined fleet, but his health declined. He became increasingly fatalistic. In April 1943, American cryptographers intercepted a message detailing Yamamoto’s inspection tour of forward bases.

Admiral Nimmitz authorized an assassination mission on April 18th, 1943. American P38 fighters intercepted Yamamoto’s transport aircraft over Bugenville and shot it down. The architect of Pearl Harbor and Midway was dead. His death was a direct consequence of American code breaking, the same

advantage that had enabled victory at Midway. The 5 minutes that began at 10:24 a.m. on June 4th, 1942 demonstrated a fundamental truth of modern warfare. Industrial capacity matters more than fighting spirit. Intelligence matters more than operational planning. The side that can replace losses faster will win. The side that can read the enemy’s plans will win. The side that can coordinate multiple forces even when things go wrong will win.

Japan entered World War II believing that superior training, superior fighting spirit, and operational excellence would overcome American industrial advantages. Midway proved this belief wrong. American pilots, many of them fresh from training, flying obsolete TBD torpedo bombers, had died attacking Japanese carriers.

Their sacrifice had achieved nothing directly, but they had pulled the Japanese combat air patrol down to sea level. They had set the conditions for the dive bombers to succeed. The system worked even when individual components failed. The Japanese system, for all its excellence in training and fighting spirit, could not adapt.

When the carriers were hit, when the fires started, when the admiral had to abandon his flagship, the entire command structure collapsed. There was no redundancy. There was no depth. The carriers were lost not just to American bombs, but to vulnerabilities in their design. Aviation fuel lines ran exposed across the hanger decks. Bombs and torpedoes were stored without adequate protection.

Damage control systems were inadequate. The carriers could deliver devastating attacks, but they could not take a punch. The contrast extended to strategic planning. Admiral Yamamoto’s plan for Midway was complex, involving multiple forces attacking in sequence with diversions and faints designed to confuse the Americans. But complexity creates vulnerability.

When the Americans knew the Japanese plans through codereing, the complexity worked against Japan. Forces were divided. The battleships were too far away to support the carriers. The invasion force could not support the carriers. The Illusian diversion drew away forces that might have made a difference at Midway. American planning was simpler. Admiral Nimttz positioned his carriers northeast of Midway. He waited for the Japanese to attack.

Then he struck with everything available. The attacks were poorly coordinated. The squadrons arrived separately, but enough attacks succeeded to destroy the Japanese carriers. Simple planning executed imperfectly was more effective than complex planning that required everything to work perfectly. The lessons of Midway would shape naval warfare for the rest of the 20th century.

Aircraft carriers would be the dominant capital ships. Battleships, for all their armor and firepower, were obsolete. The carrier that could launch air strikes from hundreds of miles away would control the seas. The nation that could build carriers faster than they could be sunk would win naval wars.

The United States built 115 carriers during World War II. Japan built 25. That ratio decided the Pacific War. The dive bomber pilots who attacked the Japanese carriers on June 4th, 1942 could not have known they were participating in a hinge moment of history. They were focused on hitting their targets, on surviving the anti-aircraft fire, on making it back to their carriers.

Lieutenant Commander McCluskey, wounded and flying a plane full of bullet holes, worried about whether he had enough fuel to reach Enterprise. Lieutenant Richard Best, who had pulled out of his dive on Kaga to attack a Kagi instead, worried about Japanese fighters pursuing him. Lieutenant Commander Max Leslie, who led the Yorktown dive bombers against Soryu, worried about the planes he had lost.

But historians would later recognize that these men, in 5 minutes of combat, had accomplished what armies fighting for years could not. They had broken the back of Japanese naval power. They had shifted the momentum of the Pacific War. They had created the conditions for Allied victory. Admiral Nimmitz would later write that the war might have lasted three more years without the victory at Midway.

Three more years of combat, three more years of losses, three more years of suffering. The Japanese pilots who died in the flames aboard Akagi, Kaga, Soru, and Hiyu were as skilled and dedicated as any aviators in history. They had trained for years. They had combat experience few could match. They had executed flawless attacks on Pearl Harbor, Darwin, son.

But on June 4th, 1940 2, they were caught on the decks of their carriers. Unable to launch, unable to defend, unable to survive. Their skill and dedication could not save them from American bombs hitting their carriers at precisely the wrong moment. Commander Fuida, who survived midway despite his broken ankles, would spend the rest of the war as a staff officer.

He would write the definitive Japanese account of the battle published in 1955 as Midway, the battle that doomed Japan. In his book, Fuida acknowledged that the Americans had achieved complete surprise, that the Japanese carriers had been caught at their most vulnerable, that the battle had decided Japan’s fate.

He gave credit to American intelligence for breaking the Japanese code, to American pilots for pressing home their attacks despite devastating losses, to American leadership for positioning forces correctly. The 5 minutes that destroyed Japan’s chance of winning began at 10:24 a.m. and ended at 10:29 a.m. In those 5 minutes, three aircraft carriers were fatally damaged.

In the hours that followed, all three would sink. By the end of the day, all four Japanese carriers that had attacked Pearl Harbor would be gone. The striking force that had dominated the Pacific for 6 months was annihilated. Lieutenant Commander McClusky returned to Enterprise with 52 bullet holes in his plane, a wound in his shoulder, and almost no fuel.

He had made the most important tactical decision of the Pacific War. His choice to continue the search, to follow the destroyer’s wake, to attack when the opportunity presented itself had changed history. He would receive the Navy Cross for his actions. But he never claimed to be a hero. He said he simply did his job.

That modesty characterized the American response to Midway. The pilots who survived did not boast of their achievement. They mourned the comrades who did not return. They prepared for the next battle. They understood that Midway was one victory in a long war, but it was the victory that ma

de all subsequent victories possible. The 5 minutes that began at 10:24 a.m. on June 4th, 1942 demonstrated that wars are decided not by single battles, but by the accumulation of advantages. Intelligence advantage, industrial advantage, training advantage, technological advantage. The side with more advantages compounded over time will win. Japan had training advantage and tactical excellence.

America had everything else. Those 5 minutes made that difference brutally clear. From that day forward, Japan fought a defensive war it could not win. The empire that had conquered half of Asia and the Pacific in 6 months would spend the next three years losing everything it had gained. The industrial might that America brought to bear, the seemingly infinite resources, the replacement carriers and aircraft and pilots would grind down Japanese resistance until nothing remained but atomic bombs and surrender. The 5 minutes that destroyed

Japan’s chance of winning were the most consequential 5 minutes of the Pacific War. They were the hinge on which the entire conflict turned. Before 10:24 a.m. on June 4th, 1942, Japan had a chance, however slim, to negotiate a favorable peace. After 10:29 a.m., Japan had already lost. Everything that followed was simply the working out of that inevitable conclusion.

The bombs that fell on Akagi, Kaga, and Soryu in those 5 minutes decided not just the battle of Midway, but the outcome of the Pacific War. This was not the result of American superiority in courage or fighting spirit. The Japanese pilots who died in the flames were as brave as any warriors in history.

This was the result of intelligence, preparation, industrial capacity, and the accumulation of small advantages. The codereers who read Japanese messages. The shipyard workers who repaired Yorktown in 72 hours. the torpedo bomber crews who died drawing Japanese fighters low. The destroyer that happened to be steaming northeast at exactly the right time to lead McClusky to his target.

All these factors combined to create 5 minutes that changed the world. Lieutenant Commander McClusky asked later about his decision to continue the search he had no choice. His orders were to find and destroy the Japanese carriers. He found them. He destroyed them. That was his job.

The fact that his judgment in those critical moments when fuel was running low and the ocean seemed empty decided the fate of nations was simply part of war. Sometimes individual decisions matter more than anyone could predict. Sometimes 5 minutes matter more than 5 years. Sometimes a single pilot’s choice to turn north instead of south changes the course of history.

The Japanese carriers Akagi, Kaga, and Soru burned for hours before sinking. The fires that started at 10:24 a.m. could not be contained. The aviation fuel, the bombs, the torpedoes stored throughout the ships kept exploding. Bulkheads collapsed. Decks buckled. Men trapped below decks died in the flames or drowned when compartments flooded.

The ships that had seemed invincible in December 1941 were gone by dawn on June 5th, 1942. 5 minutes 300 seconds. The time it takes to make a cup of coffee. The time it takes to walk a city block. The time it takes to change the world. At 10:24 a.m. on June 4th, 1942, Japan still had a chance. At 10:29 a.m., that chance was gone – consumed by the flames burning aboard three aircraft carriers in the middle of the Pacific Ocean.

News

CH2 The P-51’s Secret: How Packard Engineers Americanized Britain’s Merlin Engine

The P-51’s Secret: How Packard Engineers Americanized Britain’s Merlin Engine August 2nd, 1941, Detroit, Michigan. Inside the Packard Motor Car…

CH2 What Eisenhower Whispered When Patton Forced a Breakthrough No One Expected

What Eisenhower Whispered When Patton Forced a Breakthrough No One Expected December 22nd, 1944. One word kept echoing through…

CH2 Why Churchill Refused To Enter Eisenhower’s Allied HQ – The D-Day Command Insult

Why Churchill Refused To Enter Eisenhower’s Allied HQ – The D-Day Command Insult The rain that morning in late May…

CH2 When German Engineers Tore Apart a Mosquito and Found the Glue Stronger Than Steel

When German Engineers Tore Apart a Mosquito and Found the Glue Stronger Than Steel The smell of wood and resin…

CH2 How An “Untrained Cook” Took Down 4 Japanese Planes In One Afternoon

How An “Untrained Cook” Took Down 4 Japanese Planes In One Afternoon December 7th, 1941. 7:15 a.m. The mess deck…

CH2 How One Gunner’s ‘ILLEGAL’ Sight Turned the B-17 Into a Killer Machine

How One Gunner’s ‘ILLEGAL’ Sight Turned the B-17 Into a Killer Machine October 14th, 1943. The sky above Germany…

End of content

No more pages to load