Japanese Zeros Were Said To Be Unstoppable – Until One American Pilot Accidentally Discovered This

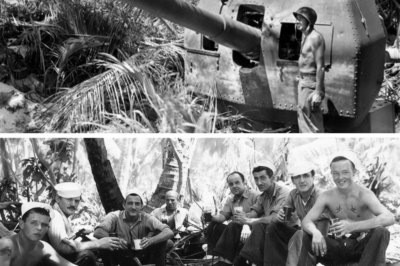

Lieutenant Richard Bong’s P38. Lightning shuddered violently as 20 millimeter cannon rounds tore through the left engine cowling. At 18,000 ft above the Solomon Islands, he was alone, his wingman already spiraling into the Pacific Ocean below, trailing black smoke. The August 1943 sun blazed through his canopy as he threw the twin boomed fighter into another desperate banking turn.

But the Japanese zero behind him matched the maneuver effortlessly, closing the distance with predatory precision. Bong had been trained at the best fighter schools in America. He knew every defensive tactic in the manual. Barrel rolls, split S’s, Chandel, scissors maneuvers. He had tried them all in the last 90 seconds, and the Zero pilot had countered each one with casual efficiency.

Now the enemy fighter was less than 200 yd behind him, positioned perfectly in his vulnerable 6:00. Guns lined up for the killing shot that would send Bong to join his wingman in the ocean. His instrument panel was a chaos of warning lights. Oil pressure dropping on the damaged engine. Air speed bleeding off as he fought to keep the nose up. altitude winding down as gravity and battle damage conspired against him.

In perhaps 10 more seconds, the Zero’s guns would finish what they’d started, and Richard Bong would become another statistic in the brutal arithmetic of Pacific Air Combat. Then, with death staring him in the face and no options remaining in the fighter pilot’s playbook, Bong did something that every instructor had warned him would kill him instantly.

He rolled the P38 completely inverted, wheels pointing at the sky, and shoved the control stick violently forward. The Lightning’s nose dropped toward the ocean in a screaming vertical dive. But Bong wasn’t diving normally. He was plunging toward the Pacific upside down with blood rushing into his skull so fast that his vision turned crimson and the instrument panel disappeared into a red blur.

For two seconds that felt like an eternity, Richard Bong flew blind through negative G forces that no training manual said his aircraft could survive. The P38’s twin Allison engines screamed in protest. Loose equipment and spent shell casings floated up from the cockpit floor and slammed into the canopy above his head.

His oxygen mask felt like it was trying to tear itself off his face. Every blood vessel in his eyes felt ready to burst. When he finally rolled the aircraft right side up at 12,000 ft, having dropped 6,000 ft in those two terrifying seconds, the zero was gone. Not just behind him, gone completely, vanished from the sky as if it had never existed.

Bong circled cautiously, scanning every quadrant of the sky, but found nothing. The Japanese fighter that had been seconds away from killing him had simply disappeared. What Richard Bong didn’t know in that moment, gasping for breath and wiping blood from his eyes, was that he had just accidentally discovered a maneuver that would change the entire Pacific Air War.

A desperate, impossible, suicidal looking trick that would break the Japanese Zero’s reign of terror over Allied pilots and ultimately help turn the tide of the war tide of the war in the Pacific. And within months, what began as one terrified pilots’ instinctive panic move would become whispered fighter pilot wisdom that would spread across every airfield from Guadalcanal to the Philippines.

This is the story of how American pilots learned to fly upside down to survive and how that discovery transformed the deadliest aircraft in the Pacific theater from an unstoppable killing machine into a target that American fighters could finally beat. It’s the story of innovation born from desperation and of how the laws of physics ultimately proved more powerful than the most maneuverable fighter plane ever built.

To understand why Bong’s accidental discovery was so revolutionary, you need to understand just how completely the Japanese Zero dominated the Pacific skies in 1942 and early 1943. When American pilots first encountered the Mitsubishi A6M0 in combat, they couldn’t believe what they were seeing.

Continue below

This Japanese fighter violated every assumption American military intelligence had made about enemy capabilities. The Zero could turn inside any Allied fighter with contemptuous ease. It could climb faster, fly farther, and operate at higher altitudes than anything the Americans had. In the early battles over the Philippines, Wake Island, and the Dutch East Indies, Japanese pilots flying zeros were achieving kill ratios that seemed impossible. For every three Japanese aircraft shot down, the Allies were losing nine.

In some engagements, the ratio was even worse. The aircraft itself was a masterpiece of lightweight engineering. A designer, Jiro Horikoshi, had created a fighter that weighed just 3,700 lb empty compared to over 5,000 lb for American fighters like the P40 Warhawk. This weight savings came from radical design choices.

The Zero had no armor plating to protect the pilot. The fuel tanks were unprotected, lacking the self-sealing technology that American aircraft employed. The airframe itself was built to minimum stress tolerances, sacrificing durability for maneuverability. But in dog fighting performance, these sacrifices created a fighter that seemed supernatural.

The Zero could complete a 360° turn in just under 16 seconds at combat speeds. An American P40 required 23 seconds for the same maneuver. When two fighters merge in combat, 7 seconds might as well be an eternity. It meant that every time an American pilot tried to turn with a zero, the Japanese fighter would complete its circle and end up on the American’s tail with guns lined up for an easy kill.

Before we continue, I’d love to know where you’re watching from and what you know about the Pacific Air War. Drop a comment below and let me know if you’d heard this story before. And if you’re enjoying these deep dives into World War II history, hit that subscribe button so you don’t miss the next one.

These stories take serious research to get the details right, and knowing you’re out there makes it all worthwhile. American pilots were dying by the dozens because they were trying to fight the zero on its own terms. Fighter tactics in 1942 were still heavily influenced by World War I dog fighting doctrine. Pilots were taught to turn, to get inside the enemy’s circle, to maneuver until they could bring their guns to bear.

This worked beautifully against German fighters in Europe, which were heavier and less maneuverable than their Allied counterparts. But in the Pacific, this doctrine was a death sentence. Lieutenant Commander John Thatch, one of the Navy’s most innovative tacticians, watched his pilots die in training exercises against captured Zeros and became obsessed with finding a solution.

He spent weeks analyzing the Zero’s capabilities and realized something crucial. Yes, the Zero could turn better than anything America had. Yes, it could climb faster, but the Zero’s lightweight construction created vulnerabilities that could be exploited if American pilots stopped trying to turn with it.

American fighters had advantages the Zero couldn’t match. The P38 Lightning, P47 Thunderbolt, and F4 U Corsair all had more powerful engines that gave them superior speed in level flight and especially in dives. They had rugged construction that could survive battle damage that would tear a zero apart.

Their fuel systems were designed to tolerate violent maneuvering without starving the engines of fuel. And crucially, their pilots were protected by armorplating and reinforced cockpits. Thatch developed what became known as the weave, a defensive maneuver where two American fighters would fly in coordination, protecting each other from Japanese attacks.

It worked and it saved lives, but it required perfect coordination between wingmen and it was fundamentally defensive. It could help American pilots survive, but it didn’t give them a way to actually beat the zero in combat. For that, they needed something else, something that would come from desperation rather than tactical planning.

The combat encounter that changed everything happened on April 7th, 1943 over the Russell Islands in the Solomon’s chain. Major Thomas Lynch of the 39th Fighter Squadron flying a P38 Lightning found himself in exactly the situation that had killed so many of his fellow pilots. Eight Japanese zeros had bounced his flight from above.

And in the chaos of the initial merge, Lynch became separated from his wingmen. Now he was alone at 20,000 feet with multiple enemy fighters trying to maneuver onto his tail. Lynch was an experienced pilot, a pre-war veteran who had flown almost daily since Pearl Harbor. He knew the odds he was facing. He also knew that trying to turn with the zeros would be suicide.

His P38 was faster than the enemy fighters, but they had altitude advantage, and if he tried to simply run away in level flight, they would catch him before he could build up enough speed. He needed to break contact immediately, but every standard escape maneuver he knew required him to turn, which would let the zeros close the distance even further. In that moment, Lynch made a decision that seemed insane.

He rolled his P38 completely inverted and pushed the stick forward, initiating a vertical dive while upside down. The world inverted around him. The ocean that had been below was now above. The sky that had been above was now below, and the P38, built like a tank compared to the fragile Zero, plunged toward the ocean at increasing speed, while Lynch’s vision turned red from negative G forces.

What happened next stunned Lynch as much as it would later stun the Japanese pilots. The Zeros couldn’t follow. When they tried to roll inverted and push into the dive to maintain pursuit, their lightweight airframes began to shutter and warp under the negative G forces. Worse, their fuel systems designed for positive G forces during climbing and turning couldn’t handle the inverted pressure.

Fuel stopped flowing to the engines. carburetors starved. Some of the zero engines simply quit entirely, leaving their pilots to glide helplessly while Lynch’s P38 screamed away at everinccreasing speed. Lynch didn’t just escape. At 12,000 ft, he rolled right side up, pulled back on the stick, and used his massive speed advantage to zoom back up to altitude.

The zeros, scattered and confused by his impossible maneuver, were now below him and slower. The hunter had become the hunted. Lynch dove on two of them from above, using his superior speed and the element of surprise. His 650 caliber machine guns converged on a zero that never saw him coming. The Japanese fighter disintegrated under the hail of bullets.

When Lynch returned to base and climbed out of his cockpit, his face was covered in small red dots. Burst blood vessels from the negative G forces had created hundreds of tiny hemorrhages across his skin. His eyes were bloodshot, the whites almost completely red. He had a splitting headache that would last for 3 days.

But he was alive and he had just discovered something that would change everything. Lynch didn’t keep his discovery to himself. That evening, over drinks in the pilot’s tent, he described exactly what he had done and what had happened. The younger pilots listened with a mixture of disbelief and fascination. Flying inverted was dangerous.

Pushing into a dive while inverted was suicidal, or so they had been taught. But Lynch was standing there alive with two confirmed kills to show for it. and he insisted that the zeros physically couldn’t follow him through the maneuver. The physics of what Lynch had discovered were actually straightforward once you understood them.

In normal flight, gravity pulls down on a pilot with one g of force. During a normal dive, pulling the stick back to curve downward creates positive G forces, pressing the pilot down into his seat. Fighter pilots trained constantly to handle high positive G’s, learning to tense their muscles and control their breathing to maintain consciousness under forces that could reach seven or eight G’s in violent maneuvers.

But an inverted dive created negative G forces, pushing the pilot up out of his seat and forcing blood into his head instead of his legs. Human beings are poorly adapted to negative G’s. Even two or three negative G’s can cause unconsciousness in untrained pilots. The blood vessels in the eyes and face burst easily under the reversed pressure. Vision degrades rapidly as blood floods the retinas.

It’s an unpleasant, painful, disorienting experience. But the critical discovery was that while human pilots could train themselves to tolerate brief periods of negative geforce, aircraft fuel systems couldn’t adapt. The Zero’s carburetor was designed to work with fuel flowing down from tanks mounted above the engine.

When the aircraft went inverted and then pushed into a dive, gravity suddenly pulled the fuel away from the carburetor intake. The engine would sputter, cough, and often quit entirely. The zero pilot would find himself flying a glider while his American opponent accelerated away. American aircraft had a crucial technological advantage the Zero lacked.

Many US fighters, particularly the P38 and later models of the P47 and Corsair, used fuel injection systems rather than carburetors. Fuel injection could maintain consistent fuel delivery regardless of the aircraft’s orientation. A P38 could fly inverted for extended periods without the engines missing a beat.

This seemingly minor technical difference suddenly became a life ordeath advantage in combat. The tactics spread through the American fighter squadrons, not through official channels, but through the informal network that fighter pilots have always relied on. When you were about to fly into combat where the slightest edge might keep you alive, you listened to veterans who had survived. And the veterans were increasingly all telling the same story.

If a zero gets on your tail, don’t turn. Roll, inverted, and dive. The zero can’t follow. Then use your speed to zoom back up and attack from advantage. Pilots started calling it different names. the split S when done from altitude, the inverted escape when used defensively, the negative G dive in formal debriefings.

But informally among themselves, pilots called it going upside down on them, and it became the first thing experienced pilots told rookies arriving fresh from statesside training. The official training manual still warned against inverted flight as dangerous and disorienting. But in the Pacific, it was becoming standard procedure. Captain Robert D.

Haven of the Seventh Fighter Squadron scored his first kill using the inverted dive in July 1943. A Zero had gotten behind him during a bomber escort mission near New Georgia. DeHaven rolled inverted, pushed into the dive, and watched in his mirror as the Zero’s engine quit trying to follow him. He recovered at 8,000 ft, climbed back up, and caught the Zero still trying to restart its engine.

It was the easiest kill of his career, and he would use the same tactic to score 13 more victories before the war ended. The physiological effects of the maneuver were brutal, but survivable. Flight surgeons on Guadal Canal began keeping records of pilots who regularly performed inverted dives, and the data was both fascinating and disturbing.

Nearly every pilot who used the tactic reported burst blood vessels in the eyes and face. Headaches lasting hours or even days were universal. Some pilots experienced temporary vision problems. A few lost consciousness briefly during the most violent negative G encounters. But none of that mattered because the alternative was death. Pilots would joke darkly that they’d rather have a headache and red eyes than aostumous metal.

The flight surgeons documented the effects, but made no attempt to discourage the tactic. They understood what the pilots understood. In air combat against the zero, you needed every advantage you could find, and a few burst blood vessels were a cheap price to pay for survival.

What made the inverted dive particularly devastating was that it completely reversed the tactical situation. Before this discovery, when a zero got on an American fighter’s tail, the American pilot was in serious trouble. His options were limited. His life expectancy measured in seconds. But once pilots mastered the inverted dive, suddenly it was the zero pilot who was in trouble. The American would roll inverted and dive.

The Zero couldn’t follow and within seconds the American was below with massive speed advantage. Then he would pull up in a zoom climb using his momentum to rocket back above the Zero and now he was in the perfect attack position with the sun behind him. Japanese pilots were completely unprepared for this tactical revolution.

Their training emphasized turning combat, exploiting the Zero’s magnificent maneuverability to get inside an opponent’s circle. They had been taught that American fighters were heavy and clumsy, that they couldn’t turn or climb, that they were easy prey if you could just get into a turning fight with them.

None of their training addressed what to do when an American fighter suddenly rolled inverted and disappeared in a screaming dive that their zeros couldn’t follow. Japanese pilot Lieutenant Saburo Sakai, one of Japan’s highest scoring aces, wrote about his confusion and frustration when he first encountered American pilots using the inverted dive.

He described carefully maneuvering into position behind a P38, lining up for what should have been an easy kill, only to watch in disbelief as the American rolled completely upside down and dove away. When Sakai tried to follow, his Zero’s engine sputtered and quit, forcing him to break off the attack while his opponent escaped.

What frustrated Sakai even more was that the Americans would then immediately climb back up and attack from above using their superior speed and the altitude advantage they had gained in the dive. The tactical situation had been completely reversed in just a few seconds. The hunter had become the hunted and there was nothing Sakai or his fellow zero pilots could do about it except avoid getting into tail chase situations in the first place.

By late 1943, the inverted dive had evolved from desperate survival tactic to deliberate combat strategy. American squadron commanders were teaching it openly now, despite the fact that official doctrine still frowned on inverted flight. Colonel Neil Kirby, commanding the 475th Fighter Group, told his pilots bluntly in their mission briefings, “If you try to turn with a zero, you die. If you try to climb with a zero, you die.

Roll inverted, dive, use your speed, and attack from above. That’s how you survive. That’s how you win. The P38 Lightning proved particularly effective at exploiting the inverted dive because of its unique twin boom design. The aircraft’s distinctive shape made it instantly recognizable, and Japanese pilots learned to be wary when they saw the twin boomed silhouette. P38 pilots developed a reputation for aggressiveness and unpredictability.

They would deliberately bait zeros into tail chases, then use the inverted dive to escape and reverse the situation. It became a cat-and- mouse game, but now the Americans were increasingly the cats. Captain Thomas Maguire, who would eventually become the second highest scoring American ace of the war with 38 victories, used the inverted dive to devastating effect over the Philippines in 1944.

In one engagement over Lady Gulf, he deliberately slowed his P38 to entice a Zero into attacking position. When the Japanese pilot took the bait and closed to firing range, Maguire rolled, inverted, and dove. The Zero pilot attempted to follow and his aircraft literally came apart in midair under the negative G stress.

The wings folded upward, the lightweight airframe collapsed, and the Zero tumbled into the ocean in pieces. Maguire hadn’t even needed to fire his guns. The tactic worked with other American fighters too, though the technique required modifications for different aircraft. The F4 U Corsair with its massive Pratt and Whitney R28000 engine could perform inverted dives that were even more violent than the P38s.

Corsair pilots learned to roll inverted and simply let the aircraft’s weight and power carry them down in screaming vertical dives that no zero could hope to follow. Marine Corps pilots flying Corsaires from Henderson Field on Guadal Canal used the inverted dive to rack up impressive kill ratios against Japanese fighters that had previously seemed unbeatable.

The P47 Thunderbolt, nicknamed the Jug because of its barrel-shaped fuselage, was the heaviest of the American single engine fighters. That weight was a disadvantage in turning combat, but it became a massive advantage in diving. P47 pilots could roll inverted and dive so fast that they approached the speed of sound, reaching velocities where the aircraft’s controls became sluggish and dangerous.

But Japanese fighters couldn’t come close to matching these speeds, and P47 pilots exploited their weight advantage ruthlessly. By 1944, the tactical situation in the Pacific had completely reversed. Kill ratios that had once favored the Japanese were now running heavily in favor of the Americans. For every American fighter shot down, the US was destroying three, four, sometimes five Japanese aircraft.

The Zero, which had once ruled the Pacific skies with impunity, was now increasingly a liability rather than an asset. Its lightweight and lack of protection, which had made it so maneuverable, also made it fragile and vulnerable to American tactics that exploited its weaknesses. Japan desperately tried to counter the American tactical evolution.

Engineers developed new fighters like the J2M Ryden and the Kai 84 Hayate with more powerful engines and better high-speed handling. But these aircraft arrived too late and in too few numbers to make a difference. And even these improved fighters couldn’t match the diving performance of American aircraft or maintain engine power during negative G maneuvers.

The fundamental physics that made the inverted dive effective couldn’t be engineered away quickly enough to matter. More critically, Japan was losing its experienced pilots at a catastrophic rate. The men who had dominated the early years of the Pacific War were dead, shot down in the Solomons over New Guinea above the Philippines.

The replacement pilots being thrown into combat had minimal training, sometimes fewer than a hundred flight hours before they faced American veterans who had survived dozens or even hundreds of combat missions. These inexperienced Japanese pilots stood no chance against Americans who knew how to exploit every advantage their aircraft offered.

Richard Bong, the pilot whose desperate accident in August 1943 had started it all, went on to become America’s highest scoring ace with 40 confirmed victories. He refined the inverted dive into an art form, often deliberately baiting Japanese fighters into attacking positions just so he could demonstrate the maneuver. Other pilots would watch his gun camera footage in amazement as he calmly rolled inverted, dove away from pursuing zeros, then climbed back up, and destroyed his confused opponents from above.

The tactic’s effectiveness wasn’t limited to fighter versus fighter combat. American bomber pilots adopted modified versions of the inverted dive to escape Japanese fighters that attacked their formations. While a fully loaded bomber couldn’t perform the violent negative G maneuvers that fighters could, bomber pilots learned that rolling partially inverted and diving could still break lock from pursuing zeros long enough for defensive gunners to get clear shots.

Dozens of bomber crews credited this tactic with saving their lives when Japanese fighters tried to press home attacks. The psychological impact of the inverted dive on Japanese pilots was perhaps as important as its tactical effectiveness. Fighter combat is as much about confidence and morale as it is about technology and tactics.

In early 1943, Japanese pilots had been supremely confident, secure in the knowledge that their zeros could outturn and outclimb anything the Americans had. By late 1943, that confidence was shattered. Japanese pilots knew that if they committed to attacking an American fighter, there was a good chance their opponent would simply roll inverted and escape, then return from above with all the advantages. The psychological edge had shifted entirely to the Americans.

The inverted dives influence extended far beyond World War II. After the war, fighter tactics instructors analyzed what had worked in the Pacific and incorporated those lessons into training doctrine. The split S maneuver, essentially a formalized version of the inverted dive, became a standard part of fighter pilot training.

Pilots flying jets in Korea used variations of the tactic against MiG 15. In Vietnam, American pilots facing agile Sovietbuilt fighters rediscovered that diving away from turning combat and using speed and altitude to dictate engagement terms was still the key to survival and victory. The Navy’s fighter weapons school, better known as Top Gun, was established in 1969 specifically to teach American pilots how to fight outnumbered against agile opponents.

The curriculum emphasized many of the same principles that pilots had discovered fighting zeros in the Pacific. Use your aircraft’s strengths. Avoid fighting on your opponent’s terms. Exploit speed and energy rather than trying to outturn more maneuverable fighters.

The lessons learned over the Solomon Islands in 1943 were still being taught to F14 and F-18 pilots decades later. Thomas Lynch, the pilot who had turned Bong’s accident into a deliberate tactic, didn’t survive the war. He was shot down and killed over the Philippines in March 1944, not in air-to-air combat, but by anti-aircraft fire while strafing Japanese positions at low altitude. He was 27 years old.

The inverted dive couldn’t protect against ground fire, and Lynch died doing exactly what he had taught his squadron to do. Press the attack, take risks, and never give the enemy a chance to recover. His Medal of Honor citation credited him with 12 confirmed victories, and praised his innovative tactical leadership. The inverted dive represented something profound about how wars are actually won.

It wasn’t a product of careful planning by generals or innovative designs by engineers. It was discovered accidentally by a desperate pilot doing something everyone had told him was impossible. It was refined through trial and error by men who had to learn fast or die. And it spread not through official channels, but through the informal networks that connect people facing the same deadly challenges.

And it worked because it exploited fundamental physics that no amount of Japanese engineering could overcome. The story also reveals how narrow the line between victory and defeat can be in aerial combat. The Zero was genuinely an outstanding aircraft and in the hands of experienced pilots, it was absolutely lethal, but it had vulnerabilities that could be exploited if opposing pilots could just figure out how.

For more than a year, American pilots died by the hundreds because they couldn’t crack the puzzle. Then, Richard Bong rolled inverted in a moment of desperation, survived by accident, and suddenly the puzzle was solved. The zero hadn’t changed. American aircraft hadn’t changed, but the tactics had changed, and that made all the difference.

Today, a restored P38 Lightning sits in the National Museum of World War II aviation in Colorado Springs. The aircraft, painted in the colors of Richard Bong’s plane, still bears the name Marge after Bong’s fiance. Next to it, museum curators have placed an information placard that describes the inverted dive and its role in turning the tide of the Pacific Air War.

Visitors can look at that graceful twin boommed fighter and imagine what it must have taken to roll that aircraft inverted 18,000 ft above the ocean and push into a dive that seemed certain to end in death. The Japanese Zero fighters that once dominated the Pacific are now museum pieces, too. Restored examples displayed in aviation museums around the world. They’re beautiful aircraft, elegant and purposeful in their design.

Standing next to one, you can see exactly what made them so deadly and why American pilots feared them. But you can also see the lightweight construction, the thin aluminum skin, the minimal structure. Looking at a zero with the knowledge of history, you can understand why this magnificent fighter couldn’t follow American planes through the inverted dive that broke its dominance.

The lesson of the inverted dive extends beyond aviation history into every field where innovation matters. Sometimes the solution to an impossible problem comes not from better equipment or more resources, but from someone desperate enough to try something everyone says won’t work.

Richard Bong wasn’t supposed to survive that August day in 1943. He did something that violated every rule and every procedure, but he survived. And in surviving, he handed American pilots the key to defeating an enemy that had seemed unbeatable. The story is a reminder that in warfare, in technology, in any competitive endeavor, the advantage doesn’t always go to whoever has the best equipment.

It goes to whoever figures out how to use their equipment most effectively. The Zero was probably the better dog fighter right up until the end of the war. But American pilots learned not to dog fight. They learned to roll inverted, dive away, and use physics as their ally. They learn to fight on their terms rather than the enemy’s terms.

That lesson, born in desperation over the Solomon Islands, remains relevant in any conflict where opponents are evenly matched. Richard Bong survived the Pacific War with more aerial victories than any other American pilot. But he didn’t survive the peace. On August 6th, 1945, the same day the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, Bong was killed testing a new P80 jet fighter in California. He was 24 years old.

The irony of the timing wasn’t lost on those who knew him. The man who had pioneered the tactic that helped win the Pacific Air War died on the day that ensured the war would end. He never got to see the full impact of what his desperate improvisation in August 1943 had accomplished.

But his legacy lived on in the hundreds of pilots who survived the war because they had learned to fly upside down when they needed to. In the restored P38s that fly at air shows today, occasionally performing the split S maneuver that Bong pioneered. in the fighter pilot training programs that still teach the same fundamental principle. Use your strengths, avoid your opponent’s strengths, and never be afraid to do something that seems crazy if it might keep you alive.

The inverted dive, born from one pilot’s terror and desperation, became a piece of tactical wisdom that would outlive everyone who fought in the war that created it. The Japanese Zero was unstoppable until one American pilot accidentally discovered something that changed everything. That discovery wasn’t a new weapon or a better aircraft.

It was simply the willingness to fly upside down when every instinct and every training manual said it would kill you. Sometimes that’s all it takes to turn the tide of history. One person desperate enough to try the impossible and lucky enough to survive it.

News

CH2 THE DOCTOR WHO DEFIED H.I.T.L.E.R: The German Surgeon-Sniper Who TURNED His Rifle on the SS – And Became The Shadow On the Battle of the Bulge

THE DOCTOR WHO DEFIED H.I.T.L.E.R: The German Surgeon-Sniper Who TURNED His Rifle on the SS – And Became The Shadow…

CH2 Why One Squadron Started Painting “Fake Damage” — And Achieved Overwhelming Result In Just in One Month Against 40 Enemy Fighters

Why One Squadron Started Painting “Fake Damage” — And Achieved Overwhelming Result In Just in One Month Against 40 Enemy…

CH2 Japanese Troops Thought They Were A “Light” Force — Until They Wiped Out 779 of Them in One Night

Japanese Troops Thought They Were A “Light” Force — Until They Wiped Out 779 of Them in One Night At…

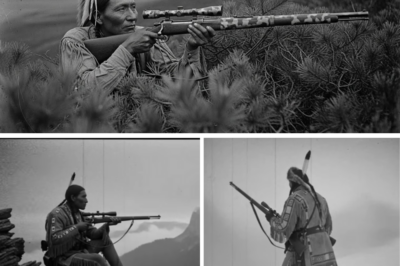

CH2 THE SHADOW WOLF: The Greatest Native Sniper to Ever Live in World War II – Yet His Name Almost Disappeared From History

THE SHADOW WOLF: The Greatest Native Sniper to Ever Live in World War II – Yet His Name Almost Disappeared…

CH2 Inside the Ford’s Willow Run Revelation — How Luftwaffe Officers POWs Stood Frozen as B-24s Rolled Out Every 63 Minutes, And Their Face Went Pale When They…

Inside the Ford’s Willow Run Revelation — How Luftwaffe Officers POWs Stood Frozen as B-24s Rolled Out Every 63 Minutes,…

CH2 The U.S. Sniper Who Defied Orders with a FORBIDDEN Night-Vision Hack—And Made Entire German Patrols Vanish in the Frozen Ardennes

The U.S. Sniper Who Defied Orders with a FORBIDDEN Night-Vision Hack—And Made Entire German Patrols Vanish in the Frozen Ardennes…

End of content

No more pages to load