Japanese Troops Thought They Were A “Light” Force — Until They Wiped Out 779 of Them in One Night

At 8:17 a.m. on February 29th, 1944, Brigadier General William Chase crouched behind a coconut log on the eastern edge of Morotai Air Strip, watching through binoculars as his 1,04 men dug rifle pits in the rain soaked coral. At 51 years old, he was leading what looked like military suicide, a cavalry regiment without horses, dropped onto a Japanese-held island with orders that fit on a note card. Hold what you take.

His force was so small that Colonel Yoshio Isaki, commanding the Japanese garrison, dismissed it as a probe. Isaki kept his main battalions pointed towards Sidler Harbor, waiting for the real American landing that would never come. The Japanese had held Los Negros for 2 years, fortifying every approach with interlocking machine gun nests and pre-registered mortars.

They had turned the jungle into a killing field, and conventional military wisdom said you needed 3:1 odds to take fortified positions. Chase had brought barely enough men to hold a perimeter around one air strip. His artillery consisted of pack howitzers that could be carried by hand. His cavalry troopers had never fought dismounted. His engineers were Navy CBS who were supposed to build runways, not fight battles.

That first night, Japanese infiltrators tested the American line with grenades and swimmers. By dawn, 66 enemy dead lay inside the wire. Chase’s men had learned something the Japanese didn’t expect. A light force could be a deadly force if it knew how to weave a web instead of building a wall. For 3 days, Isaki watched and waited, convinced the Americans were too few to hold.

Then at 9:00 p.m. on March 3rd, he sent 800 of his best troops in a mass night assault across the narrow skidway, expecting to sweep the thin American line into the sea. By dawn on March 4th, 779 Japanese soldiers were dead, and the light American force was still digging in.

The rain had been falling since 0500, turning the coral dust of Morotai air strip into a slick pace that clung to everything. Chase watched his men through field glasses, noting how quickly they adapted to ground they had never seen before. The two troops of the fifth cavalry, just over 400 dismounted troopers, were digging their rifle pits on the reverse slopes of the low ridges east of the runway, exactly as he had ordered.

Not because it looked safer, but because it created killing lanes where Japanese attackers would be silhouetted against the sky while American muzzle flashes stayed hidden below the crest. The perimeter took shape like a horseshoe bent around the eastern third of the air strip.

Troop E held the northern ark where a 50-yard skidway cut through the coconut groves, the most likely avenue of approach for any serious attack. Troop G anchored the southern flank, their positions dug into the coral ridges that gave clear fields of fire across the Icel flat ground. Between them, the weapons platoon cited their 60 mm mortars and 30 caliber machine guns to create interlocking fires that would turn the open ground into a furnace.

Battery B of the 99th Field Artillery had landed with the assault waves, their pack 75 mm howitzers broken down into loads that six men could carry. The guns were already imp placed 500 yd behind the rifle line, close enough to provide direct fire support, but far enough back to avoid being overrun in the first rush.

Each howitzer could throw a 14lb shell 8,000 m. But tonight, they would be shooting at ranges measured in hundreds of yards, turning high explosive rounds into oversized grenades that could clear Japanese soldiers from coconut logs and coral outcroppings with surgical precision.

Chase had learned his trade in the peacetime army, where cavalry officers studied Napoleon and Grant, but spent their days managing horses and teaching recruits to ride. The irony was not lost on him that his greatest battle would be fought by cavalry men who had left their mounts in Australia.

What mattered now was not horsemanship, but the ability to think in terms of mobility and firepower, to see ground not as terrain to be held, but as a web to be woven. The CBS of the 40th Naval Construction Battalion were supposed to rebuild the Air Strip, but Chase had other plans. Commander Rasmuson’s men were excellent shots and better diggers than most infantry.

They would extend the perimeter to include the entire runway, creating a defensive box that could accommodate landing craft and supply dumps while maintaining all-around security. The CBS understood the mission without lengthy explanations. dig fast, shoot straight, and turn a captured air strip into an operational base before the Japanese could mount a serious counterattack.

Continue below

The portable surgical hospital had been landed in the second wave, its doctors and medics setting up in a coral pit behind the artillery positions. Chase had insisted on bringing the medical team because he knew what was coming. The Japanese would not accept the loss of Morotai without a fight, and when they came, they would come in overwhelming numbers designed to crush his small force in a single blow.

Men would die and others would be wounded badly enough to need immediate surgery. The portable hospital was not a luxury. It was a necessity that might determine whether his force could hold long enough for reinforcements to arrive. As the afternoon wore on, Chase walked the perimeter, checking positions and talking to squad leaders.

The men were tired but alert, their weapons clean and ammunition distributed according to the load plans worked out during the voyage from Oro Bay. Each rifleman carried eight clips for his M1 Garand, plus two fragmentation grenades and a bayonet. The machine gunners had 30 belts of 30 caliber ammunition per gun with more being distributed from the beach as fast as the supply parties could carry it forward.

The mortar crews had registered their weapons on key terrain features, the skidway, the main trail from the west, the beach approaches from the north. Each gun had 50 rounds of high explosive immediately available with another 100 rounds stacked in the ammunition pits being dug by the CBS. The mortars were the perimeter’s insurance policy capable of dropping plunging fire behind cover that rifles and machine guns could not reach.

By 1700 hours, the perimeter was as ready as time and manpower allowed. The tripwire alarms were in place. sea ration cans filled with coral pebbles that would rattle when disturbed. The password for the night was thunder and lightning, chosen because Japanese soldiers had difficulty pronouncing the thesis and L sounds.

Centuries knew to challenge anyone moving after dark and to shoot first if the response was not immediate and correct. Chase established his command post in a coral pit 50 yard behind the center of the line with telephone wires running to each troop and battery.

The radio was tuned to the frequency used by the destroyers offshore, ready to call for naval gunfire if the perimeter was threatened with being overrun. The USS Mullan was standing by just outside the harbor mouth. Her 5-in guns loaded and trained on pre-plotted targets along the expected approaches. As darkness fell, the rain intensified, reducing visibility to a few yards and muffling sounds that might have given warning of approaching infiltrators.

Chase knew this was both blessing and curse. The weather would make it harder for Japanese observers to count his positions and estimate his strength, but it would also make it easier for small groups of enemy soldiers to penetrate the perimeter and cause havoc in the rear areas.

The first probes came at 2100 hours just as the last light faded from the western sky. Single shots cracked from the northern sector, followed by the distinctive sound of grenades exploding in the rifle pits. Chase grabbed the telephone to troop E and heard Sergeant Miller’s voice, calm and professional. Three or four infiltrators, sir. We got two of them. The others pulled back.

This was the beginning, not the main event. The Japanese were testing his lines, looking for weak points, and measuring the response times of his reserve. Throughout the night, small groups of enemy soldiers probed different sections of the perimeter. They came silently through the coconut groves, crawling close enough to throw grenades into foxholes before disappearing back into the darkness.

The Americans responded with disciplined fire, short bursts from rifles and machine guns that conserved ammunition while eliminating threats. By dawn, 66 Japanese bodies lay inside the wire, proof that the perimeter was not the hollow shell it appeared to be from a distance. The first gray light of March first revealed the true cost of the night’s work.

Chase counted the bodies as he walked the perimeter with his company commanders, noting how the Japanese infiltrators had died. Most had been caught in the killing lanes between positions, cut down by interlocking machine gun fire before they could reach the American foxholes. Others lay twisted among the trip wires.

Victims of the coral-filled cans that had given away their approach routes in time for defenders to react. Sergeant McGill from G Troop pointed to a cluster of eight bodies near his forward revetment. They came straight up the draw. Sir must have thought they could rush us in the dark.

The dead men wore the uniforms of the first independent mixed regiment elite troops who had been fighting in the Pacific since 1942. Their weapons were well-maintained Arisaka rifles and type 999 light machine guns. Proof that Isaki was not sending his expendable garrison troops on these probes. He was testing the American defenses with his best men. The ammunition count told a clearer story than the body count.

Battery B had fired 37 rounds of 75mm high explosive, mostly at muzzle flashes in the treeline. The machine gun crews had expended over 2,000 rounds of 30 caliber ammunition, fired in disciplined bursts that kept the barrels from overheating while maintaining continuous fields of fire.

Each mortar crew had dropped an average of 15 rounds, walking their fire along the approaches to break up concentrations before they could form. Chase ordered the bulldozers forward to clear additional fields of fire. The D4 Caterpillars had come ashore with the second wave. Their operators volunteering to work under direct fire to improve the defensive positions.

By noon, they had knocked down 50 yards of coconut trees along the northern approach, creating an open killing field that extended the effective range of the rifle pits from 200 to 400 yd. The fallen logs were dragged into position as additional obstacles, their twisted trunks creating barriers that would channel any attack into predetermined lanes.

The portable surgical hospital had worked through the night by lamplight, treating 15 wounded Americans and documenting their injuries for the medical reports that would follow the battle. Seven men had been hit by grenade fragments, their wounds cleaned and dressed before they returned to their positions.

Three had taken rifle bullets in non-vital areas and were marked for evacuation on the next supply run. Two had been killed outright, their bodies wrapped in shelter halves and placed in a temporary grave registration point behind the command post. By mid-afternoon, the perimeter had evolved from a hastily dug line of rifle pits into a sophisticated defensive system that maximized the killing power of every weapon.

The 60 mm mortars were positioned to provide overlapping coverage of the entire front, their crews. Having memorized the range and deflection settings for every piece of key terrain within 1500 yardds, the 81 mm mortars were cited near the center of the position, close enough to the command post for Chase to personally direct their fires against targets beyond the range of the lighter tubes.

The machine gun positions had been improved with overhead cover and additional ammunition storage. Each gun now had 40 belts immediately available, enough to sustain continuous fire for 20 minutes without resupply. The gunners had cut alternate positions for their weapons connected by shallow trenches that would allow them to shift their fires or relocate if their primary positions were compromised by enemy mortars or direct fire weapons.

Commander Raasmuson’s CBS had transformed the supply situation by building a coral road from the beach to the perimeter, allowing supply trucks to bring forward ammunition, rations, and medical supplies without exposing the carriers to observed fire from Japanese positions in the hills.

The road also provided a covered route for evacuating wounded men to the aid station and eventually to the landing craft that would carry them to hospital ships offshore. The artillery positions reflected Chase’s understanding of how the battle would develop. Battery B’s four pack howitzers were imp placed in a rough diamond pattern, each gun capable of supporting the others if the position was attacked from any direction.

The guns were dug into coral pits with overhead protection against mortar fragments. their crews having prepared ammunition for both direct and indirect fire missions. Each howitzer had 60 rounds of high explosive immediately available with another 100 rounds stacked in covered ammunition points 50 yards to the rear.

The fire direction center occupied a reinforced coral pit adjacent to the command post. Its plotting boards and communication equipment protected against everything except a direct hit by artillery or aerial bombs. The forward observers with each rifle company maintained continuous telephone contact with the guns, ready to call for fire against any target that presented itself.

The fire plans included concentrations on every likely approach route with range and deflection data computed and verified by actual registration fires on selected reference points. Naval gunfire coordination had been established with the destroyers offshore. Their 5-in guns providing extended range and hitting power that the pack howitzers could not match.

The USS Melany maintained a continuous patrol station just outside Hyenne Harbor. Her gunnery officer having plotted target areas along the coast and in the interior where Japanese reinforcements might concentrate before launching an attack. The ship could deliver fire missions on 30 seconds notice. her radar controlled guns accurate enough to drop shells within 50 yards of friendly positions.

Chase spent the evening hours walking the perimeter again, checking the night defensive fires and ensuring that each position understood its role in the overall plan. The trip wires had been reset after the morning’s clearing operations, their locations marked on sketches that would prevent friendly casualties from defenders who forgot where the obstacles had been placed. The password for the night was Boston and Tea Party.

Again, chosen for sounds that Japanese infiltrators would find difficult to pronounce correctly under stress. The intelligence picture remained incomplete but suggestive. Prisoners taken during the night attacks had revealed that Isaki still believed the American landing was a reconnaissance in force designed to gather information rather than establish a permanent foothold.

Japanese radio intercepts indicated that significant enemy forces remained concentrated around Seedler Harbor, waiting for what their commanders expected would be the main American assault. This misreading of American intentions was buying Chase precious time to strengthen his positions and prepare for the inevitable counterattack. As full darkness settled over the perimeter, the sounds of the night began.

Japanese mortars opened fire from positions in the hills, their rounds falling randomly among the American positions without observed adjustment. The fire was harassing rather than destructive, designed to prevent sleep and wear down the defender’s nerves rather than destroy specific targets.

Chase ordered his own mortars to respond with counter fire, more to maintain morale than from any expectation of hitting the mobile enemy weapons. The real test would come when Isaki finally committed his reserve forces to a coordinated attack designed to overrun the American positions before reinforcements could arrive.

Until then, Chase’s men would hold their carefully prepared web and wait for the Japanese commander to make his fatal mistake. The sound of landing craft engines cutting through the morning surf on March 2nd announced the arrival of reinforcements that would transform Chase’s knife edge perimeter into something resembling a proper defensive position.

The rest of the fifth cavalry regiment came ashore in waves, their boots splashing through the shallows as they carried ashore the heavy weapons and additional ammunition that would be needed for the fight everyone knew was coming. Behind them came the full 99th field artillery battalion.

their remaining pack howitzers and fire direction equipment, adding depth and precision to the supporting fires that had kept the perimeter alive through two nights of probing attacks. Major General Swift’s decision to commit the remainder of Task Force Brewer reflected his understanding that Chase’s initial landing had created an opportunity that could not be wasted.

The Japanese had revealed their defensive plans by their pattern of responses, keeping their main forces concentrated around Seedler Harbor while allowing what they still believed was a reconnaissance force to dig in unmolested on the opposite side of the island. Each hour that Isaki delayed his counterattack gave the Americans additional time to strengthen their positions and bring ashore the combat power needed to hold against a determined assault.

The 40th Naval Construction Battalion came ashore with their heavy equipment, including additional bulldozers and compressors that would allow rapid improvement of the defensive positions. Commander Rasmuson immediately put his men to work expanding the Coral Road network, creating supply routes that would support the larger force now occupying the beach head.

The CBS also began construction of a more substantial aid station using pre-fabricated sections and coral fill to create a medical facility that could handle the casualties expected from a major enemy attack. The perimeter expanded to accommodate the additional troops and equipment.

Its boundaries pushed outward to include the entire airrip and the high ground that commanded the approaches from the west. The first squadron took responsibility for the northern sector, including the critical skidway that remained the most likely avenue for a major Japanese attack. The second squadron occupied the southern positions, their fields of fire covering the beach approaches, and the coral ridges that provided observation over the entire defensive area.

Artillery coordination became more sophisticated with the arrival of the complete battalion fire direction center and its complement of trained observers. The 99th Field Artillery now had 12 pack howitzers in position, arranged in three batteries that could mass their fires on any threatened sector or engage separate targets simultaneously. Each battery maintained telephone communication with forward observers positioned with the rifle companies, ensuring that supporting fires could be delivered within minutes of any request. The guns were registered on reference

points throughout the area, their crews having fired adjustment rounds to verify range and deflection data for every significant terrain feature within their 8,000 m range. The arrival of company C, 168th Anti-aircraft artillery, brought the first heavy weapons capable of engaging targets beyond small arms range.

The 90mm guns were positioned to provide air defense for the beach head, but their crews were trained to engage ground targets when necessary. Each gun could fire a 20 lb projectile at nearly 3,000 ft pers, giving the defenders a capability to engage Japanese positions at ranges where the pack howitzers might not be effective. Anti-aircraft defense was further strengthened by the landing of company A 211th anti-aircraft artillery equipped with quad 50 caliber machine gun mounts that could engage both air and ground targets.

The multiple 50 caliber weapons were particularly effective against personnel targets. Their combined rate of fire capable of putting 2,000 rounds per minute into any area within their 3m range. The gun crews position their weapons to cover the gaps between infantry positions, creating additional killing zones that would channel any attack into predetermined areas.

Mine warfare became a critical component of the defensive plan as additional engineer personnel came ashore with their specialized equipment. The engineers laid anti-personnel mines along the most likely approach routes, focusing their efforts on the areas where terrain features would naturally channel attacking forces.

The mines were supplemented by improvised obstacles created from coral rocks and fallen trees, barriers that would slow an attack and expose the attackers to concentrated defensive fires. Communication systems were expanded to handle the increased complexity of coordinating fires from multiple supporting weapons.

Additional telephone lines connected all major units to the central fire direction center, while radio networks provided backup communications and allowed coordination with naval vessels offshore. The communication improvements ensured that supporting fires could be masked quickly against any threat regardless of which sector of the perimeter was under attack.

Naval gunfire support was enhanced by the arrival of additional destroyers that could provide continuous coverage of the area around Los Negros. The ships maintained patrol stations that allowed their 5-in guns to engage targets throughout the island. Their radar controlled weapons providing all-weather capability that complemented the land-based artillery.

Fire support coordination centers aboard the destroyers worked directly with the shore-based fire direction centers, ensuring that naval gunfire could be integrated with artillery fires without danger to friendly forces. Intelligence collection improved significantly with the arrival of additional personnel trained in interrogation and document translation.

Japanese prisoners taken during the nightly probing attacks provided information about enemy unit locations and intentions, while captured documents revealed details of the defensive plans that Isaki had prepared for different sectors of the island.

The intelligence picture that emerged confirmed that the Japanese commander continued to expect the main American attack at Seedler Harbor, leaving his forces poorly positioned to respond to the actual threat developing at Mote Airstrip. Medical facilities were expanded to handle the casualties expected from a major battle.

The portable surgical hospital was supplemented by additional medical personnel and equipment brought ashore with the reinforcements, creating a facility capable of performing life-saving surgery under field conditions. Evacuation procedures were established to move wounded personnel from the forward positions to the aid station and eventually to hospital ships offshore, ensuring that injured men would receive appropriate treatment as quickly as possible.

Supply operations were systematized to ensure continuous flow of ammunition, rations, and other essential materials to the forward positions. The CBS constructed additional storage areas and improved the road network connecting the beach to the perimeter, creating a logistics system capable of supporting sustained combat operations. Ammunition supply points were established behind each major unit position with sufficient stocks to support several days of intensive fighting without resupply from the beach. By evening, the transformed perimeter bore little resemblance to the hastily prepared positions that had

survived the first two nights of fighting. What had begun as a thin line of rifle pits had evolved into a comprehensive defensive system that integrated multiple weapon systems and supporting elements into a coherent plan. designed to destroy any attacking force through coordinated fires and obstacles.

The question now was whether Isaki would continue to underestimate American strength and intentions or whether Japanese intelligence would finally recognize that the landing at Hyain Harbor represented a permanent lodgement rather than a temporary reconnaissance. The first mortar rounds began falling at 2100 hours on March 3rd.

their explosions walking methodically across the American perimeter as Japanese forward observers adjusted fires from concealed positions in the hills. Chase recognized the pattern immediately. This was not the random harassment fire of the previous nights, but deliberate preparation fires designed to suppress defensive positions before an assault.

He grabbed the telephone to the fire direction center and ordered immediate counterbatter fire on all suspected enemy mortar positions. Then called for the destroyers offshore to begin their pre-planned fires on the assembly areas where Japanese infantry would be forming up for the attack. Isaki had finally committed to his assault, massing elements of the second battalion, first independent mixed regiment, and supporting units from the 229th Infantry for what Japanese doctrine called a night penetration attack. The plan was tactically sound.

Multiple columns would advance simultaneously along different routes with the main effort directed against the skidway where the terrain offered the best approach to the American positions. Supporting attacks would pin down defenders on other sectors while infiltration teams penetrated the perimeter to attack command posts and artillery positions from the rear.

The Japanese preparation fires intensified at 2130 with mortars and small field pieces pounding the forward positions while machine guns ra the areas behind the front lines to prevent reinforcement or resupply.

The bombardment was heavier than anything the Americans had experienced during the previous nights with incoming rounds falling at the rate of one every few seconds across the entire perimeter. Chase ordered his men to take cover in their fighting positions and wait for the fires to lift, knowing that the infantry assault would begin the moment the artillery stopped.

Sergeant McGill’s forward revetman in G troops sector drew particular attention from the Japanese gunners. its position 35 yards in front of the main line, making it a natural target for elimination before the assault began. McGill had prepared for this moment, his position reinforced with additional sandbags and equipped with extra ammunition that would allow sustained fire against attacking infantry. His mission was simple but critical.

Hold the outpost long enough to break up the enemy assault formations and give the main line time to prepare for the survivors who made it through the initial killing zone. The artillery preparation ended abruptly at 2215. The sudden silence more unnerving than the bombardment had been. Chase knew that Japanese infantry were already moving forward through the darkness.

Their approach concealed by the noise of the bombardment and the smoke that hung over the battlefield. He ordered illumination rounds from the mortars, their magnesium flares casting harsh white light over the approaches and revealing the first wave of attackers already within 200 yards of the perimeter. The Japanese came forward in dense formations that reflected their confidence in overwhelming the thin American line through sheer numbers and shock action.

The assault battalions had been told they were attacking a reconnaissance force that could be swept aside by determined attack, and their tactics reflected this assessment. Companies advanced in column formation along the most direct routes to their objectives, expecting to penetrate the American positions before defensive fires could be organized effectively.

McGill’s revetment opened fire first, his Browning automatic rifle cutting down the lead elements of the company attacking up the skidway. The muzzle flashes from his position immediately drew return fire from Japanese light machine guns and rifle grenades, their impacts throwing coral fragments and smoke around his fighting position.

He continued firing in short bursts, conserving ammunition while maintaining effective fire on the attackers, who were now clearly visible in the light of the flares drifting overhead. The main perimeter erupted in defensive fire as the full scope of the Japanese attack became apparent.

Multiple companies were advancing simultaneously against different sectors, their movements coordinated to prevent the Americans from shifting forces to meet the main threats. The machine gun crews in each position opened fire at maximum rate. Their interlocking fires creating lanes of destruction that the attacking infantry could not avoid.

Tracer ammunition drew bright lines across the battlefield showing exactly where the Y defensive fires were concentrated and revealing gaps that subsequent waves of attackers tried to exploit. Artillery support from the 99th field artillery was immediate and devastating. The pack howitzers had been pre-registered on all the likely approach routes and their crews began firing within seconds of receiving fire missions from the forward observers.

High explosive shells burst among the advancing Japanese formations, their fragments cutting down men who had survived the small arms fire from the perimeter. The guns fired at maximum rate, their crews working with practiced efficiency to maintain continuous fire on targets that were often less than 300 yd from friendly positions.

Naval gunfire from the destroyers offshore added another dimension to the defensive fires. The USS Mullan closed to within 2,000 yards of the beach. Her 5-in guns firing over open sights at Japanese positions in the treeline. The ship’s radar could track individual groups of attackers, allowing precise engagement of targets that were invisible to observers on shore.

Each 5-in round carried a 54-lb warhead that could destroy an entire squad of infantry with a single hit. The Japanese assault reached its climax around midnight when infiltration teams succeeded in penetrating the perimeter at several points, creating confusion and forcing American units to fight in multiple directions simultaneously.

Some of the infiltrators had been equipped with American uniforms and equipment, allowing them to approach close to command posts and supply areas before being detected. Others used captured American radio frequencies to transmit false orders, adding to the confusion as units tried to determine which communications were legitimate.

McGill’s position came under direct assault by an entire Japanese platoon that had worked its way to within grenade range before being detected. When his bar jammed during the firefight, he grabbed an M1 rifle from a wounded man and continued firing until that weapon also malfunctioned.

Left with only his pistol and bayonet, he ordered his remaining unwounded soldier to fall back to the main line while he held the position alone. The Japanese platoon launched three separate attacks against the Revetment, each one stopped by McGill’s determined resistance and accurate fire from supporting positions. The intensity of the fighting reached levels that exceeded anything in the previous combat experience of most participants.

Individual positions were firing ammunition at rates that would normally be sustained only for a few minutes, but the attacks continued for hours without letup. Machine gun crews fired 8,770 rounds during the night, changing barrels repeatedly to prevent weapons from overheating. Mortar crews dropped over 400 rounds of high explosive, their tubes becoming so hot that water had to be poured on them between fire missions.

By 03, 100 hours, the Japanese attack was clearly failing. The multiple assault columns had been broken up by defensive fires before they could reach their objectives, while the infiltration teams had been hunted down and eliminated by reserve forces and support personnel fighting as infantry. The carefully planned night penetration had turned into a series of isolated firefights where superior American firepower and defensive preparation overcame Japanese numerical advantage and fighting spirit.

Dawn revealed the full extent of Isaki’s miscalculation with Japanese bodies scattered across the entire front of the American perimeter in numbers that exceeded even the most optimistic estimates of enemy casualties. The first light of March 4th revealed a battlefield that told the story of Isaki’s catastrophic miscalculation more clearly than any intelligence report could have done.

Japanese bodies lay in windows across the killing fields, their positions marking exactly where the American defensive fires had been most effective. Chase walked the perimeter with his company commanders, counting the dead and assessing the condition of his own forces. After seven hours of continuous combat, the numbers were stark and decisive. 779 enemy dead counted and buried by noon against 61 Americans killed and 244 wounded.

McGill’s forward revetment had become the focal point of the night’s fighting with 105 Japanese bodies counted in the immediate vicinity of his position. The sergeant himself had been found at dawn with his bayonet still fixed, surrounded by the evidence of a final hand-to-hand struggle that had cost the attacking platoon its entire strength.

His Medal of Honor citation would later record the simple fact that his solitary stand had broken the main Japanese assault before it could reach the perimeter’s main line of resistance. The ammunition expenditure figures provided additional evidence of the battle’s intensity.

Battery B of the 99th Field Artillery had fired over 600 rounds of 75 mm high explosive, nearly exhausting their basic load before supply parties could bring forward additional shells from the beach dumps. The machine gun crews had collectively fired over 40,000 rounds of 30 caliber ammunition. Their weapons maintained in action throughout the night by armorer teams who replaced overheated barrels and cleared stoppages under direct fire.

Chase ordered immediate resupply operations to replace the ammunition expended during the night fighting, knowing that Isaki might attempt another assault before the American position could be further strengthened. Landing craft shuttled between the beach and the offshore transports, bringing ashore not only ammunition but also additional medical supplies for treating the wounded and materials for improving the defensive positions. The portable surgical hospital had operated at maximum capacity throughout the night.

its surgeons performing life-saving operations by lamplight while mortar rounds fell nearby. The arrival of the second battalion, Seventh Cavalry Regiment, on the morning of March 4th provided Chase with the additional manpower needed to expand his defensive perimeter and begin offensive operations against remaining Japanese positions.

The Fresh Battalion came ashore with full equipment and ammunition loads. Their men eager to join a battle that had already proven the effectiveness of American defensive tactics against Japanese night assault doctrine. Major General Swift followed them ashore, bringing with him the authority to expand the operation beyond its original reconnaissance mission.

Relief operations began immediately with the battle tested second squadron, fifth cavalry, rotating out of the front lines to rest and refit while fresh units took over their positions. The relief was conducted according to standard procedures designed to maintain continuous defensive coverage while allowing exhausted troops to recover from their ordeal.

Each departing unit briefed its replacements on the tactical situation in their sector, passing along hard one knowledge about Japanese tactics and the most effective defensive techniques. The 82nd Field Artillery Battalion came ashore with the reinforcements, bringing 12 additional pack howitzers that would provide the fire support needed for offensive operations beyond the original perimeter.

The new artillery pieces were imp placed in positions that allowed them to engage targets throughout Los Negros Island. Their longer range and greater ammunition capacity complementing the guns that had proven so effective in the defensive battle. Fire direction centers were expanded to coordinate the fires of both artillery battalions, creating a comprehensive fire support system capable of supporting multiple simultaneous operations.

Intelligence reports from prisoners and captured documents revealed that Isaki’s assault had consumed the majority of his combat effective forces, leaving him with insufficient strength to mount another major attack against the American positions.

The Japanese commander had committed his reserves to the night assault in the belief that overwhelming the American reconnaissance force would end the threat to his garrison. Instead, he had destroyed his own capacity for further offensive action while leaving the Americans in possession of an airfield that could support major operations throughout the Admiral T Islands. Construction activities resumed with renewed urgency as the CBS worked to make Mamode Air Strip operational for fighter aircraft that would provide air cover for future operations. The runway required extensive grading and the installation of steel matting to

support the weight of loaded aircraft. work that proceeded around the clock despite the continuing threat from Japanese snipers and mortar fire. Fuel storage facilities were established near the strip along with maintenance shops and ammunition storage areas that would support sustained air operations.

The 12th Cavalry Regimental Combat Team landed on March 6th, bringing Chase’s total strength to over 4,000 men supported by tanks, additional artillery, and engineer units capable of major construction projects. The arrival of the full regimental combat team marked the transformation of the reconnaissance in force into a full-scale amphibious assault designed to secure the entire Admiral T Islands chain.

Chase retained command of the expanded force. His successful defense having demonstrated the tactical principles that would guide the remainder of the campaign. Tank support arrived in the form of company A, 6003rd tank battalion, equipped with M5 Stewart light tanks that could provide direct fire support for infantry attacks against fortified positions.

The tanks were landed using specially modified landing craft, their crews having practiced amphibious operations during training in Australia. Each tank carried a 37mm gun and three machine guns, giving the infantry commanders mobile firepower that could engage targets beyond the range of their organic weapons. Offensive operations began on March 5th with advances across the Skidway towards Salami Plantation using the same terrain that the Japanese had attempted to exploit during their failed night attack. The advancing infantry found extensive evidence of the previous night’s carnage with abandoned weapons

and equipment marking the routes along which Isaki’s assault forces had approached the American perimeter. Resistance was light and disorganized, consisting mainly of small groups of survivors who had escaped the destruction of their parent units.

The Royal Australian Air Force arrived at Morotai on March 9th when number 77 squadron landed their P40 Kittyhawks on the newly completed runway. The Australian pilots brought with them extensive experience in Pacific combat operations. Their aircraft providing close air support and reconnaissance capabilities that had been missing during the initial phase of the operation.

Their presence also demonstrated the strategic value of the airfield that Chase’s men had defended at such cost. Zeadler Harbor fell to American forces on March 15th, completing the conquest of Los Negros and opening the anchorage that MacArthur had designated as essential for future operations in the Western Pacific.

The harbor’s capture validated the strategic concept behind the original landing, proving that a small force properly positioned and supported could achieve results far beyond what its size might suggest. The Japanese garrison that Isaki had concentrated around Seedler surrendered without significant resistance. Their combat effectiveness having been destroyed in the failed assault on Mamodi airirststrip.

The campaign’s conclusion confirmed the effectiveness of defensive tactics based on interlocking fires, pre-registered supporting weapons, and the integration of all available combat elements into a coherent defensive system. Chase’s success had demonstrated that American forces could overcome Japanese advantages in numbers and terrain knowledge through superior firepower, better coordination, and defensive positions designed to maximize killing power rather than simply occupy ground.

News

CH2 Why One Squadron Started Painting “Fake Damage” — And Achieved Overwhelming Result In Just in One Month Against 40 Enemy Fighters

Why One Squadron Started Painting “Fake Damage” — And Achieved Overwhelming Result In Just in One Month Against 40 Enemy…

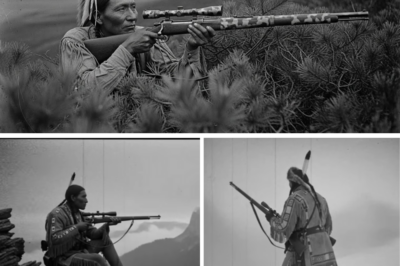

CH2 THE SHADOW WOLF: The Greatest Native Sniper to Ever Live in World War II – Yet His Name Almost Disappeared From History

THE SHADOW WOLF: The Greatest Native Sniper to Ever Live in World War II – Yet His Name Almost Disappeared…

CH2 Inside the Ford’s Willow Run Revelation — How Luftwaffe Officers POWs Stood Frozen as B-24s Rolled Out Every 63 Minutes, And Their Face Went Pale When They…

Inside the Ford’s Willow Run Revelation — How Luftwaffe Officers POWs Stood Frozen as B-24s Rolled Out Every 63 Minutes,…

CH2 The U.S. Sniper Who Defied Orders with a FORBIDDEN Night-Vision Hack—And Made Entire German Patrols Vanish in the Frozen Ardennes

The U.S. Sniper Who Defied Orders with a FORBIDDEN Night-Vision Hack—And Made Entire German Patrols Vanish in the Frozen Ardennes…

CH2 How America’s Mark 18 Torpedo Made Japanese Convoys Completely N.a.k.e.d And Defenseless

How America’s Mark 18 Torpedo Made Japanese Convoys Completely N.a.k.e.d And Defenseless September 3, 1943. The sea was a sheet…

CH2 They Mocked His “Caveman” Dive Trick — Until He Shredded 9 Fighters in One Sky Duel

They Mocked His “Caveman” Dive Trick — Until He Shredded 9 Fighters in One Sky Duel Nine German fighters…

End of content

No more pages to load