Japanese Soldiers Were Terrified When U.S. Marines Used Quad-50s to Destroy Their Banzai Charges

The morning of February 8th, 1945, dawned with a kind of heavy stillness that only came before violence. The air hung thick with moisture, and the jungle of northern Luzon steamed under a dim gray light. Sergeant Joe Mason crouched behind the steel hull of his M16 halftrack, his hands resting on the grips of the Quad-50 turret, the cold metal vibrating faintly from the idling engine beneath him. Through the drifting smoke of artillery fire, he could just make out the faint shapes of movement 400 yards away—Japanese soldiers advancing through the haze, their silhouettes merging and separating in the rising mist. The night had been long, but dawn brought no peace. Mason was twenty-four years old, a squad leader with the Fifth Marine Regiment, and until this moment, he had never once fired his new weapon system in combat.

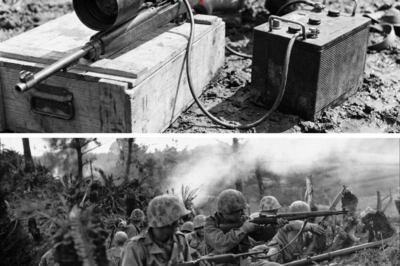

The weapon beside him was something few Marines had ever seen in use on the ground—a Frankenstein of American ingenuity and necessity. Officially, it was designated the M16 Multiple Gun Motor Carriage, a halftrack mounting four .50 caliber Browning M2 machine guns in a powered, rotating turret. It had been designed for one purpose: to fill the skies with lead and tear apart enemy aircraft before they could dive on convoys or infantry. But Luzon was not Europe. There were no Messerschmitts here, no dive-bombers or strafing runs. There were only jungles, ravines, and fanatical soldiers who charged screaming from the shadows with rifles, grenades, and bayonets.

When Mason had first seen the M16 back at Camp Pendleton, he had assumed it was for air defense and nothing else. Its bulk alone—over sixteen tons of steel and machinery—looked too cumbersome for anything else. But now, as he wiped the sweat from his brow and stared into the distant tree line, he was beginning to understand why command had decided to bring it here. The last forty-eight hours had been a nightmare. His battalion had faced seventeen banzai charges—wave after wave of Japanese infantry emerging from the jungle at night, screaming as they charged straight into machine-gun fire. Every time the Marines thought they had repelled one attack, another wave came through the gaps. The air had been thick with the smell of cordite and blood.

His commanding officer had told him the M16 wasn’t built for infantry, but there was no choice now. “It’s meant for shooting down planes,” the captain had said. “You’ll be swatting flies with a sledgehammer.” Mason hadn’t disagreed. But he also hadn’t forgotten what he’d seen. The halftrack had been equipped with four Browning M2s, each capable of firing up to six hundred rounds per minute. Together, that meant a total rate of fire of 2,400 rounds per minute, each bullet the size of a man’s thumb and capable of punching through half an inch of steel at over a thousand yards.

The first time he’d climbed into the turret, it had felt like sitting inside a machine built for destruction. The guns overlapped perfectly, their fields of fire converging into a single cone of devastation. The armor plating on the halftrack was thin—barely enough to stop small arms fire—but the power of its weapons made it feel invincible. A .50 caliber round could penetrate a light vehicle at 1,500 yards, tear a tree apart in seconds, and rip through a man’s body with ease. Mason didn’t need a manual to know what four of them firing in unison could do.

Back at camp, one of the mechanics had laughed when he first saw the Quad-50 mounted and ready. “That’s not a gun,” he’d said, shaking his head. “That’s a statement.” Another Marine had nicknamed it “the buzzsaw,” a name that stuck the moment they fired it for the first time during training. The recoil rattled bones and deafened ears, but the effect was mesmerizing—a wall of fire and lead, like watching a storm being unleashed through a set of barrels.

Now, in the jungles of Luzon, the humor was gone. There was no laughter in the mud, only fear and exhaustion. The Japanese defenders had turned every ridge into a fortress. They fought from caves, tunnels, and concealed bunkers that had been carved into the limestone months before the Americans even landed. Every night, they came at the Marines again—sometimes crawling, sometimes sprinting, always screaming. The sound of a banzai charge in the dark wasn’t something Mason could describe easily. It was a sound that reached into a man’s bones, that made even veterans grip their rifles tighter and pray that the line would hold.

In just the past three days, Fox Company’s perimeter had been overrun twice. Easy Company had nearly been wiped out the night before when a charge came through the left flank during a torrential downpour. The Marines had fought back with rifles, grenades, and machine guns, but the cost was heavy. Fourteen men dead, two more so badly wounded they’d been evacuated under fire. The faces of those men were still burned into Mason’s mind as he crouched behind the halftrack, scanning the jungle ahead.

It had been after that massacre that the battalion commander called Mason to his tent. The officer’s eyes were bloodshot, his voice raw from shouting. He pointed at the anti-aircraft halftrack parked under a camo net and asked one question. “Can that thing stop them?” Mason had hesitated, then nodded slowly. “It’ll stop anything it hits, sir,” he said. “The only question is whether we can aim fast enough.” The commander had stared at him for a long moment, then finally said, “You’ve got until dawn to find out.”

And so now, as dawn broke over the Luzon hills, Mason and his crew sat behind the Quad-50, waiting. The vehicle had arrived only twelve hours earlier, part of a Red Ball Express convoy that had fought its way through two ambushes to reach the front. The Marines had spent the night learning the controls from a Navy gunner’s mate, a young man who admitted he’d never used the weapon on ground targets before. The technical manual was useless—it talked about engaging aircraft at altitudes between five and twenty thousand feet, calculating lead times, and predicting flight paths. It said nothing about what would happen when the targets were men—hundreds of them—charging headlong across open ground.

The jungle ahead was quiet now, deceptively so. The thick canopy filtered the rising sun into long, uneven shafts of light that painted the mud and smoke in gold and shadow. Somewhere out there, Mason knew, Japanese soldiers were watching, waiting. The Marines had learned to fear that kind of silence—it always came before the storm.

He checked his ammunition belts again. Each of the four guns was loaded with armor-piercing incendiary rounds—over a thousand rounds per gun. The captain had told him to save the specialized ammo for enemy planes, but Mason hadn’t listened. There weren’t any planes left to shoot at, only men, and the enemy’s determination made them more dangerous than any aircraft.

Behind him, his crew shifted uneasily. Corporal Ramirez was hunched over the loader’s seat, wiping the sweat from his neck. Private Keegan checked the elevation controls for the tenth time. Nobody spoke. The smell of oil, sweat, and metal filled the air. Every man knew what was coming—they had seen it too many times not to recognize the signs.

At 05:58, Mason heard the sound first—a faint, rhythmic rustling in the distance, followed by the unmistakable clatter of rifles being raised. He froze, straining his ears. Then, faint but rising, came the sound they all dreaded: voices shouting in unison, harsh and defiant, the cry of men throwing their lives away for their emperor. The jungle erupted in sound.

Mason felt the vibration of the engine through his boots. He gripped the handles of the turret, staring into the gloom where the tree line began to shift and sway. Through the smoke, through the low mist of dawn, he could see them now—dark shapes moving fast, dozens, then hundreds, coming out of the trees, charging across the clearing. Bayonets glinted in the first light of morning. The sound of the banzai charge rolled across the clearing like thunder.

He didn’t think. He didn’t pray. His training took over. Mason placed his boot on the pedal that powered the turret rotation and swung the Quad-50 toward the oncoming wave. The barrels tracked smoothly, their metallic whine barely audible over the chaos. He felt the weight of every man’s eyes on him, waiting for the moment when the first trigger would be pulled, when the experiment would become reality.

The M16 halftrack had never been meant for this. It was a weapon built for the skies, designed to strike planes hundreds of feet above the ground. But now, in the mud and smoke of Luzon, it was about to be turned against something far closer, something far more personal. The jungle ahead seethed with movement, the cries growing louder. Mason’s finger hovered over the trigger, the barrels lined up perfectly with the advancing shadows.

And then, as the first figures broke into the open, he took a breath, steady and controlled, his pulse matching the rhythm of the engine beneath him. The Quad-50s were ready. The jungle was alive. The charge was coming.

And in that suspended moment—just before the first burst of fire, just before the world erupted again—Sergeant Joe Mason realized that nothing in any manual could have prepared him for what came next.

Continue below

On the morning of February 8th, 1945, at 0600 hours, Sergeant Joe Mason crouched behind the steel hole of his M16 halftrack in the dense jungle of Luzon, watching Japanese soldiers charge across a muddy clearing 400 yardds away through the smoke of artillery fire. At 24 years old, he was a Marine squad leader with zero confirmed kills using the Quad 50 mount, facing an enemy that had launched 17 banzai charges against the second battalion in just the past 48 hours.

His commanding officer had told him the M16 was designed for shooting down aircraft, and the other Marines joked that using anti-aircraft guns on infantry was like swatting flies with a sledgehammer. When Mason had first seen the M16 back at Camp Pendleton in California with its 450 caliber machine guns mounted in a powered turret, the armor even asked whether it was meant for planes or tanks.

Mason told him it was for whatever the brass ordered, but nobody had explained how to use 1,800 rounds per minute against charging soldiers. The vehicle weighed 16 tons with each of the four M2 Browning machine guns capable of firing 2,400 rounds per minute compared to a standard bars 350 rounds per minute with no turret. His mount was quad-barreled with overlapping fields of fire. The BAR was single barrel with limited range.

Captain Morris ordered him to save ammunition for enemy aircraft, but Mason loaded armor-piercing incendiary rounds anyway. By that time, the fifth marine regiment had been fighting on Luzon since January 9th, pushing inland from Lingai and Gulf, but struggling against entrenched Japanese positions in the mountains.

The terrain was brutal, dense jungle canopy, steep ridges, and cave systems that had been fortified for months. Japanese soldiers were launching coordinated attacks every night, appearing from hidden bunkers, and charging with bayonets fixed, screaming battle cries that echoed through the trees. On February 5th, a bonsai charge overran Fox Company’s perimeter. On the 6th, another broke through Easy Company’s lines.

On the 7th, three more attacks left 14 Marines dead, including two machine gunners cut down at pointblank range. That night, the battalion commander summoned Mason. The Japanese were killing his men faster than malaria, and he needed something that could stop a human wave attack. He asked whether that anti-aircraft gun could actually hit anything on the ground.

Mason explained the specifications. Each 50 caliber round traveled at 2,800 ft per second with a muzzle energy of 13,000 ft-lb, capable of penetrating armor at 1500 yd and designed to destroy aircraft engines. The commander gave him until dawn to find out what it could do to charging infantry.

The pre-dawn darkness of February 9th hung over the Luzon mountains like a burial shroud broken only by the distant rumble of artillery and the mechanical clanking of tracked vehicles moving through jungle mud. Sergeant Joe Mason pressed his back against the cold steel of the M16 halftrack, feeling the vibration of its idling engine through his spine as he watched the tree line 300 yd ahead.

The Quad50 mount loomed above him like a mechanical spider, its four barrels pointing into the gloom where Japanese soldiers had been probing their perimeter since midnight. Mason had been awake for 36 hours straight, his hands trembling, not from fear, but from exhaustion and the weight of what his commanding officer had ordered him to discover.

The MI16 had arrived at their forward position 12 hours earlier, delivered by a Red Ball Express convoy that had fought through two ambushes to reach the second battalion’s lines. Mason’s crew had spent the evening learning the weapon’s controls from a Navy gunner’s mate, who admitted he had never fired it at ground targets.

The technical manual specified engagement procedures for aircraft flying at altitudes between 5,000 and 20,000 ft with detailed charts for calculating lead times and burst patterns against bombers maintaining steady courses. Nothing in the manual mentioned what happened when you aimed four synchronized 50 caliber machine guns at human beings charging across open ground.

Corporal Frank Thomas crouched beside the turret controls, his fingers dancing over switches and dials as he ran through the firing sequence for the dozenth time that night. Each of the four M2 Browning machine guns held a belt of 160 rounds, feeding from ammunition boxes that could be reloaded in under 30 seconds by a trained crew. The gunner’s seat was cushioned and adjustable, designed for long duration flights where comfort mattered more than protection. On the ground surrounded by jungle that could conceal snipers at 50 yards, the open turret felt exposed and vulnerable.

Thomas had wrapped extra ammunition belts around the gun mounts and stacked sandbags along the vehicle’s flanks, transforming an anti-aircraft platform into something resembling a fortress. At 0545, the Japanese artillery began its preparatory barrage. Mason counted the incoming shells by their whistle and impact.

six rounds of 75 millimeter, probably from a type 94 mountain gun positioned somewhere in the ridges above their position. The shells burst in the trees behind them, sending shrapnel ringing off the halftracks armor and filling the air with the smell of cordite and splintered wood. Japanese doctrine called for a brief but intense bombardment, followed immediately by an infantry assault designed to suppress defending fire during the critical moments when attacking soldiers crossed open ground.

The first Japanese soldiers appeared at the edge of the clearing at 0552, moving in a skirmish line that stretched for 200 yards along the jungle’s edge. Mason counted at least 40 men, possibly more concealed in the undergrowth, armed with Arisaka rifles and light machine guns. Their uniforms were torn and mud stained, evidence of weeks spent living in caves and fighting a losing battle against superior American firepower.

These were not the fresh troops who had defended Luzon’s beaches in January, but veterans who had survived two months of continuous combat and knew exactly what they faced. Lieutenant Haruto Yamamoto led the charge from the center of the line, his sword raised above his head as he screamed orders in Japanese.

His men responded with the traditional battle cry that had terrified Allied soldiers across the Pacific, a sound that combined fury and desperation in equal measure. They advanced at a steady trot, not the wild sprint of a bonsai charge, but the disciplined movement of soldiers who understood terrain and timing.

Their objective was clearly the American machine gun positions that had been cutting down their night probes, and they moved with the confidence of men who had broken through marine lines before. Mason’s radio crackled with reports from observation posts scattered through the jungle. Charlie 6, this is Lima 1. Count four zero enemy infantry advancing from the north. They’re moving in extended order, spacing about 10 yards. Wait, I see more movement in the trees. Make that 6 enemy, possibly more. The transmission dissolved into static as Japanese mortar rounds began falling on the forward positions, cutting telephone lines and forcing spotters to take cover. Thomas rotated the turret to face the advancing Japanese soldiers.

The electric motors whining as four heavy machine guns swung toward their target. The M16’s fire control system had been designed for tracking aircraft that moved in predictable patterns at known altitudes, but infantry attacking across broken ground presented challenges the engineers had never considered. The gun site was calibrated for targets moving at hundreds of miles hour, not the walking pace of soldiers picking their way through jungle debris.

The Japanese advance reached the halfway point across the clearing when Mason gave the order to open fire. Thomas pressed both trigger buttons simultaneously, sending two streams of 50 caliber rounds toward the enemy line at a combined rate of 4,800 rounds per minute.

The sound was unlike anything Mason had experienced in two years of combat. Not the sharp crack of rifle fire or the steady chatter of machine guns, but a continuous roar that seemed to tear the air itself. Muzzle flashes lit the clearing like strobes, casting dancing shadows among the trees and filling the night with the acrid smoke of burning powder.

The effect on the advancing Japanese soldiers was immediate and devastating. 50 caliber rounds designed to punch through aircraft engines tore through human bodies with horrifying efficiency. Each impact sending sprays of blood and tissue across the muddy ground.

Men simply disappeared in clouds of red mist while others spun and fell as the massive bullet severed limbs and shattered bones. The careful spacing of the Japanese formation, intended to minimize casualties from artillery fire, became a liability as the Quad50’s overlapping fire swept across their entire front like a sythe. Lieutenant Yamamoto lasted perhaps 10 seconds before a burst caught him center mass, lifting him off his feet and hurling his body 20 yards backward into the jungle.

His sword spun end over end through the air, its blade catching the muzzle flashes before disappearing into the darkness. The soldiers who had followed him into the clearing began to break and run, but the Quad50’s traverse was faster than fleeing men, and Thomas methodically swept the entire area until nothing moved except the settling smoke.

The silence that followed was more terrifying than the gunfire had been. Mason’s ears rang with a high-pitched wine that would persist for days, and his nostrils burned with the smell of spent brass and blood. In 90 seconds of continuous fire, they had expended over 7,000 rounds and transformed a disciplined Japanese assault into a charal house that would haunt the dreams of every Marine who witnessed it. The psychological impact was immediate.

Word of the Quad50’s devastating effectiveness spread through both armies before dawn, carried by survivors who would never again charge across open ground with the same confidence. Word of the massacre spread through the Japanese lines like wildfire, carried by the few survivors who had crawled back through the jungle with tales that their officers initially dismissed as combat hysteria.

Sergeant Major Akira Suzuki received the first report at 0730 from a private whose left arm hung useless at his side, shredded by 50 caliber fragments. The man babbled about American guns that fired like thunder and turned soldiers into mist. his eyes wide with a terror that Suzuki had never seen in 20 years of military service.

By noon, similar accounts were filtering in from observation posts scattered throughout the mountains, each describing the same devastating weapon that could sweep entire squads from existence in seconds. The tactical implications became clear during the afternoon briefing at regimenal headquarters held in a cave system that had been carved from solid rock and reinforced with timber stolen from abandoned Filipino villages.

Colonel Teeshi Yamada studied intelligence reports that painted a picture of American firepower unlike anything encountered in previous Pacific campaigns. His staff officers, veterans of Guadal Canal and Saipan, struggled to comprehend weapons that could deliver the concentrated fire of an entire company from a single vehicle. The Americans had always possessed superior artillery and air support.

But this represented something fundamentally different. Portable devastation that could be positioned wherever the enemy chose to advance. Japanese tactical doctrine had evolved through three years of island warfare, adapting to American advantages in firepower and logistics through careful use of terrain and surprise attacks.

Their defensive positions were designed to channel enemy advances into killing zones where concentrated fire from concealed positions could inflict maximum casualties before inevitable withdrawal to secondary positions. The system had worked against conventional weapons, forcing American forces to pay heavily for each yard of ground.

But the Quad 50 changed every calculation that underpinned their strategy. Suzuki gathered his platoon leaders at 1700 hours to discuss new defensive measures, meeting in a bunker that had taken 3 weeks to construct using hand tools and explosives scavenged from unexloded American bombs.

The men who faced him represented the cream of Japanese infantry, survivors of campaigns stretching from Manuria to the Philippines. Soldiers who had adapted to every weapon the Allies could deploy against them. Their faces showed the strain of continuous combat, but also the grim determination that had made them formidable opponents throughout the Pacific War.

Lieutenant Kenji Tanaka, commanding second platoon, had witnessed the morning’s engagement from an observation post 500 yardd from the killing ground. His report was precise and methodical, delivered in the flat tone of a professional soldier describing tactical realities.

The American weapon appeared to be a modified halftrack, mounting four heavy machine guns in a powered turret capable of sustained fire that exceeded anything in the Japanese arsenal. Its effective range was at least 600 yd, possibly more, and its traverse was fast enough to engage multiple targets simultaneously across a wide front. The psychological impact was equally devastating.

Tanaka’s men had fought against flamethrowers in Napal, weapons that killed slowly and painfully, but the Quad 50 offered death so swift and complete that soldiers simply ceased to exist. Traditional Japanese infantry tactics relied heavily on the willingness of individual soldiers to accept death in service to the emperor.

But courage became meaningless when entire squads could be obliterated before they could close with the enemy. The weapon struck at the heart of Bushidto philosophy by making personal valor irrelevant in the face of overwhelming mechanical superiority. Intelligence reports suggested the Americans possessed at least three of these weapons within the second battalion’s area of operations, with more arriving daily as supply convoys fought through to forward positions.

Japanese observers had identified the distinctive silhouette of M16 halftracks moving through jungle trails that had been considered impassible for wheeled vehicles, suggesting American engineers were rapidly improving road networks to support heavy weapons deployment. The logistical implications were staggering.

Each Quad 50 required thousands of rounds of 50 caliber ammunition, tons of fuel, and specialized maintenance that could only be performed by trained technicians. Suzuki’s counterattack plans reflected the desperate improvisation that characterized Japanese tactics in the war’s final phase. Traditional frontal assaults were clearly suicidal, but infiltration tactics offered possibilities, if properly executed under cover of darkness or adverse weather.

Small teams of sappers armed with magnetic mines and satchel charges might penetrate American perimeters and destroy the weapons before they could be brought into action, though such missions would essentially be suicide operations with minimal chance of success. The evening reconnaissance patrol returned with photographs taken through captured American binoculars, showing M16 positions that had been hastily fortified with sandbags and camouflage netting.

The vehicles were protected by infantry squads armed with automatic weapons and positioned to provide interlocking fields of fire that would make close approach extremely difficult. American engineers had cleared vegetation for hundreds of yards in all directions, eliminating cover that infiltrators might use to approach undetected during night operations.

Captain Hiroshi Nakamura, the regimental intelligence officer, presented an analysis that confirmed their worst fears about American tactical evolution. Radio intercepts suggested Marine commanders were rapidly integrating quad 50 weapons into standard infantry operations, using them as mobile fire bases that could be repositioned quickly to respond to Japanese defensive measures.

The Americans were learning to coordinate these weapons with artillery and air strikes, creating layered defensive systems that could destroy attacking forces at multiple ranges simultaneously. The capture documents included technical specifications that revealed the full scope of the threat they faced. Each M2 Browning machine gun fired rounds weighing 750 grains at muzzle velocities exceeding 2,800 ft per second, delivering kinetic energy sufficient to penetrate light armor at extended ranges.

The weapons were fed from disintegrating link belts that allowed sustained fire without the lengthy reloading periods that characterized Japanese machine guns, eliminating the brief windows of vulnerability that infantry had traditionally exploited during assault operations.

Morale among the Japanese soldiers began to deteriorate as news of the Quad50’s effectiveness spread throughout their defensive network. Veterans who had survived Guadal Canal in Bugganville spoke quietly of weapons that made resistance feudal, while newer replacements asked questions about surrender procedures that would have been unthinkable weeks earlier.

Officers struggled to maintain discipline as desertions increased and sick reports multiplied. clear indicators that their force was beginning to disintegrate under psychological pressure that exceeded anything experienced in previous campaigns. The final radio transmission of the day came from an outpost positioned on a ridge overlooking the main American supply route reporting the movement of another convoy carrying what appeared to be additional M16 halftracks toward forward positions. The observer counted at least six vehicles, suggesting the Americans were massing quad 50 weapons

for a major offensive operation that would render Japanese defensive positions untenable. Suzuki acknowledged the report and began planning withdrawal operations that would preserve what remained of his command, knowing that conventional resistance had become impossible against weapons that transformed warfare itself into an exercise in mechanical slaughter.

The nightmares began on February 11th, spreading through the Japanese positions like a contagion that no medical officer could treat. Private Ichiro Watanabe woke screaming at 0200 hours, his cries echoing through the cave system until Sergeant Major Suzuki personally silenced him with a blow to the head. The young soldier had not even witnessed the Quad50 massacre, but stories told by survivors had infected his dreams with visions of comrades dissolving in sprays of blood and bone fragments.

Similar incidents occurred throughout the night as exhausted men jolted awake from sleep that offered no escape from the mechanical thunder that haunted their waking hours. The psychological contamination spread beyond individual nightmares into collective behavior that undermined military discipline at every level.

Centuries abandoned their posts rather than risk exposure to weapons that killed without warning, while patrol leaders falsified reports rather than venture into areas where American halftracks might be positioned. The traditional Japanese acceptance of death in battle depended on the possibility of honorable sacrifice, but the Quad 50 offered only meaningless obliteration that served no tactical purpose and honored no military tradition.

Lieutenant Harudo Yamamoto’s younger brother, Second Lieutenant Tero Yamamoto, arrived at the regimenal command post on February 12th, carrying orders from divisional headquarters and a personal letter from their father in Kyoto. The letter written before news of Harudo’s death had reached Japan spoke of family honor and the sacred duty to resist American invasion regardless of personal cost.

Taro read the words aloud to assembled officers who had witnessed the devastating effectiveness of weapons that made such sacrifices irrelevant, creating a cognitive dissonance that shattered traditional military values more effectively than any enemy propaganda campaign. The sound of the Quad 50 became a Pavlovian trigger that induced panic.

Responses throughout the Japanese defensive network. Soldiers who heard the distinctive roar of four synchronized machine guns would freeze in terror or flee their positions without orders, abandoning weapons and equipment in their desperate attempts to escape destruction they knew was inevitable.

Officers attempting to maintain discipline found themselves facing men whose nervous systems had been fundamentally rewired by exposure to firepower that exceeded human capacity to resist or comprehend. Radio intercepts revealed the extent to which fear had penetrated Japanese communications networks. Operators used coded references to avoid speaking directly about the American weapons, calling them thunder gods or iron demons in transmissions that became increasingly incoherent as stress accumulated.

Messages that should have contained tactical information instead carried warnings about supernatural forces that no conventional military response could counter, reflecting the breakdown of rational analysis in the face of technological superiority that seemed almost magical in its devastating efficiency.

The Americans monitoring these transmissions through captured radio equipment and interrogation of prisoners began to understand the psychological weapon they had accidentally created. Captain James Morris, commanding the Marine Company equipped with three M16 halftracks, received intelligence briefings that described Japanese morale collapse on a scale unprecedented in Pacific warfare.

Enemy soldiers were surrendering rather than face the Quad 50 weapons, abandoning defensive positions that had cost weeks of labor to construct and fortify. Corporal James Harris, monitoring Japanese radio frequencies from his position in the battalion command post, recorded conversations that provided insight into the enemy’s deteriorating mental state.

Officers spoke openly of withdrawal options that violated explicit orders to hold their positions at any cost, while enlisted men discussed surrender procedures in direct contradiction of military regulations that demanded death before dishonor. The intercepted communications painted a picture of an army losing its fundamental cohesion as traditional values crumbled under the weight of technological reality.

The first organized Japanese surrender occurred on February 14th when an entire platoon approached Marine lines under a white flag improvised from a torn undershirt. The 37 soldiers who emerged from a cave complex had endured 72 hours of indirect fire from quad 50 weapons positioned almost a mile away.

Their positions systematically destroyed by armor-piercing rounds that penetrated rock and timber with equal ease. The platoon leader, a veteran sergeant with ribbons indicating service in China and the Dutch East Indies, explained through an interpreter that resistance had become a form of suicide that served no military purpose.

Similar incidents multiplied throughout the following week as news of successful surrenders spread through the Japanese defensive network despite efforts by officers to suppress such information. Small groups of soldiers began appearing at marine outposts with improvised white flags, their weapons abandoned and their uniforms indicating units that had previously fought with fanatical determination.

Intelligence officers conducting preliminary interrogations discovered that these men had not been defeated in conventional military terms, but psychologically broken by exposure to weapons that challenged their fundamental understanding of warfare. The Quad 50 weapons had evolved beyond their original anti-aircraft role into instruments of psychological warfare that operated on levels their designers had never intended.

Marine crews reported that Japanese positions would often be abandoned before the weapons were even brought into action, with enemy soldiers fleeing at the first sound of tracked vehicles approaching through the jungle. The mere possibility of encountering the devastating firepower was sufficient to trigger panic responses that rendered defensive positions untenable.

Sergeant Major Suzuki gathered his remaining officers for what he privately knew would be their final tactical conference, held in a bunker that trembled with the distant impact of artillery rounds. The men who faced him represented the fragments of units that had been shattered not by direct combat, but by the psychological pressure of facing weapons that made traditional military values obsolete.

Their uniforms were torn and stained, their eyes hollow with exhaustion and something deeper that resembled the shell shock he had witnessed among American prisoners in earlier campaigns. The decision to withdraw came not from higher command, but from the collective recognition that continued resistance served no tactical purpose and would result only in the meaningless destruction of soldiers whose sacrifice could achieve no strategic objective.

Suzuki drafted the withdrawal order using military language that preserved the fiction of tactical repositioning, though every man present understood they were abandoning positions they had been ordered to hold until death rather than face weapons that killed without honor or meaning.

The evacuation began that night under cover of darkness that provided psychological comfort, even though the Americans possessed nightfighting capabilities that made concealment largely irrelevant. Soldiers moved in small groups through jungle trails that had been carefully prepared over weeks of defensive construction, carrying only personal weapons and abandoning heavy equipment that had become useless against enemies who fought with mechanical precision rather than human courage.

The retreat marked the effective end of organized Japanese resistance in this sector, accomplished not through conventional military defeat, but through the systematic destruction of morale that had sustained their forces throughout 3 years of hopeless warfare against overwhelming American industrial superiority. The cave complex at Hill 212 represented the last organized Japanese resistance in the second battalion sector.

A labyrinthine fortress carved from volcanic rock and reinforced with steel beams salvaged from destroyed bridges. Intelligence estimates placed 300 enemy soldiers inside the tunnels commanded by Colonel Yamada himself and supplied through underground passages that connected to artillery positions on the reverse slope.

The natural formation provided protection against conventional weapons while offering multiple firing positions that could sweep the approaches with interlocking fields of fire from concealed machine gun nests. Captain Morris received the attack order at 0500 hours on February 18th, accompanied by detailed reconnaissance photographs that revealed the tactical challenge his Marines would face.

The cave entrances were positioned halfway up a steep slope covered with fallen logs and volcanic boulders, providing natural obstacles that would channel any assault into predetermined killing zones. Japanese engineers had spent weeks improving these defenses with barbed wire, mines, and camouflaged fighting positions that could accommodate individual riflemen armed with telescopic sighted Aerosaka rifles capable of accurate fire at ranges exceeding 600 yardds. The preliminary bombardment began at 0630 with a

concentration of 105mm howitzer shells that lasted 20 minutes and achieved minimal tactical effect against targets protected by solid rock. Artillery observers reported secondary explosions indicating ammunition storage areas, but the main defensive positions remained intact and capable of resistance.

Smoke rounds fired during the final phase of the barrage provided concealment for advancing infantry while simultaneously marking the beginning of the assault phase that would test the Quad50 weapons against prepared defenses for the first time.

Sergeant Mason’s M16 advanced up the slope in company with two other halftracks, their tracks grinding against loose rock as they climbed toward positions that allowed direct fire into the cave entrances. The vehicles moved in single file along a trail that engineers had blasted from the hillside using demolition charges, creating a route barely wide enough for tracked vehicles and offering no space for tactical maneuvering if the lead element encountered obstacles or enemy fire.

Japanese mortar rounds began falling around the advancing halftracks at 0715. their explosion sending rock fragments ringing off armor plating without causing significant damage to the heavily protected vehicles. Corporal Thomas rotated his turret toward the largest cave entrance, a opening approximately 12 ft wide and 8 ft high that intelligence photographs had identified as the main access point to the underground complex.

The Quad50 weapons had been loaded with a mixture of armor-piercing incendiary rounds and standard ball ammunition, creating a combination designed to penetrate rock barriers while producing incendiary effects that would create secondary fires inside the confined spaces where Japanese soldiers had taken shelter.

The technical challenge lay in maintaining accuracy while firing upward at targets partially concealed by natural rock formations that deflected rounds and created unpredictable ricochet patterns. The first burst of quad 50 fire struck the cave entrance at 0722, sending four streams of 50 caliber rounds into the opening at a combined rate of fire approaching 5,000 rounds per minute.

The armor-piercing rounds chewed through rock barriers that had been constructed to stop rifle bullets and artillery fragments, while incendiary elements ignited ammunition and equipment stored inside the tunnels. Secondary explosions indicated that the concentrated fire had reached Japanese supply areas, creating fires that would consume oxygen and produce toxic gases throughout the underground complex.

Japanese soldiers attempting to return fire from concealed positions found themselves facing weapons that could suppress entire sections of the defensive line simultaneously. The Quad50’s overlapping fields of fire meant that any position revealing itself by shooting became the target of devastating return fire that could reduce fighting positions to rubble in seconds.

Traditional Japanese defensive tactics relied on carefully coordinated fire from multiple positions, but the American weapons made such coordination impossible by destroying any position that disclosed its location through muzzle flash or movement. Colonel Yamada’s command bunker, located deep inside the cave system and connected to forward positions through communication tunnels, became a trap as smoke and toxic gases from burning equipment filled the confined spaces with vapors that made breathing difficult and reduced visibility to mere feet. Radio

communications with forward elements failed as antennas were destroyed by concentrated fire, while telephone lines were severed by rounds that penetrated deep into the rock formation and cut cables that had been considered completely protected from surface bombardment.

The psychological effect on Japanese soldiers trapped inside the burning caves exceeded anything experienced in previous engagements with American forces. Men who had endured artillery bombardments and flamethrower attacks found themselves facing weapons that seemed capable of reaching them regardless of the protection offered by solid rock barriers.

The continuous roar of Quad 50 fire created acoustic effects inside the tunnels that amplified the sound to levels that damaged hearing and induced disorientation among defenders who could not determine the source or direction of incoming rounds. Second, Lieutenant Taro Yamamoto led a desperate counterattack at 0845, emerging from a concealed tunnel entrance with 30 soldiers armed with rifles, light machine guns, and magnetic anti-tank mines that might disable the American halftracks if applied at close range. The assault achieved complete surprise and advanced to within 50 yards of Mason’s position before being

detected by Marine infantry positioned to protect the Quad 50 weapons from exactly such infiltration attempts. The resulting firefight lasted less than 3 minutes and ended with the complete destruction of the Japanese force, including Yamamoto himself, who died attempting to place a magnetic mine on the M16’s track assembly.

The systematic destruction of the cave complex continued for 2 hours as marine crews methodically targeted every opening large enough to conceal a fighting position. Armor-piercing rounds penetrated deep into the tunnels while incendiary elements created fires that spread throughout the underground network, consuming equipment and forcing surviving Japanese soldiers toward exits that were covered by American weapons.

The Quad50 fire was so intense that rock faces began to disintegrate under the continuous impact of heavy machine gun rounds, creating landslides that sealed some tunnel entrances while exposing others to direct fire. At 10:30 hours, a white flag appeared at the main cave entrance, followed by Colonel Yamada himself leading 43 surviving members of his command.

The Japanese commander’s uniform was torn and blackened by smoke, his face bearing the hollow expression of a man who had witnessed the complete failure of defensive tactics that had served the Imperial Army throughout decades of warfare. His formal surrender was conducted according to military protocol.

Though both sides understood that the Quad50 weapons had achieved victory through technological superiority rather than traditional military virtues that had previously determined battlefield outcomes. The Hill 212 engagement demonstrated the complete tactical dominance the Quad 50 weapons could achieve against even the strongest defensive positions when properly supported by conventional infantry and artillery.

Japanese resistance in the sector collapsed within hours as news of the fortress’s fall spread through remaining enemy units, many of which began withdrawal operations without attempting further resistance against weapons that had proven capable of destroying any position regardless of natural or artificial protection. The silence that settled over the Luzon Mountains after February 20th was more profound than any ceasefire agreement could have achieved, broken only by the distant rumble of American supply convoys carrying ammunition and equipment that would no longer be needed for combat operations.

Sergeant Joe Mason sat on the hull of his M16 halftrack, cleaning 50 caliber machine gun barrels that had fired over 30,000 rounds in 12 days of continuous operations. Each barrel worn smooth by the friction of bullets that had redefined warfare in ways no military theorist had anticipated.

The Quad 50 weapons had achieved tactical objectives that conventional forces would have required weeks to accomplish, transforming what should have been a prolonged siege into a route that scattered Japanese defenders across hundreds of square miles of jungle terrain. The psychological aftermath proved more complex than the tactical victory.

Corporal Frank Thomas developed a tremor in his right hand that made fine motor control difficult, a physical manifestation of stress that military physicians attributed to prolonged exposure to the concussive effects of sustained heavy weapons fire. His medical records would later show hearing loss consistent with acoustic trauma, though the psychological components of his condition resisted clinical diagnosis and treatment.

Similar symptoms appeared throughout the Marine units that had operated quad 50 weapons, suggesting that the devastating effectiveness of these weapons extracted costs from their crews that were not immediately apparent during combat operations. Intelligence officers conducting post-battle analysis discovered that Japanese resistance had collapsed across a front, extending far beyond the second battalion’s operational area, with enemy units withdrawing from positions they had occupied for months rather than risk encounters with weapons that had demonstrated the ability to destroy any defensive position. Radio intercepts

revealed communications between Japanese commanders discussing withdrawal routes that avoided areas where American halftracks might be deployed, indicating that the psychological impact of the Quad 50 weapons had altered enemy tactical planning throughout the entire Luzon campaign.

The captured Japanese soldiers provided insights into the mental state of an army that had been psychologically defeated by weapons that challenged fundamental assumptions about warfare and military honor. Colonel Yamada, interviewed three days after his surrender, described the experience of commanding troops who had lost faith in their ability to resist American technological superiority through traditional military virtues.

His officers spoke of soldiers who had served with distinction in China and throughout the Pacific, but became ineffective when faced with weapons that seemed to violate natural laws governing the relationship between courage and survival. American military observers studying the tactical implications of Quad 50 employment began developing new doctrines that incorporated lessons learned from the Luzon operations.

The weapons had proven capable of achieving fire superiority that exceeded anything in the existing arsenal, but their logistical requirements and limited mobility restricted their tactical employment to specific types of terrain and operational situations. Technical reports noted that each M16 consumed ammunition at rates that required dedicated supply operations while maintenance demands exceeded the capabilities of standard field repair facilities.

The broader strategic implications became apparent as intelligence reports from other Pacific theaters described similar psychological effects wherever quad 50 weapons had been employed against Japanese forces. Enemy commanders were adapting their tactics to avoid direct confrontation with American heavy weapons, preferring withdrawal to defensive positions that had previously been considered impregnable.

This tactical evolution suggested that the psychological impact of the weapons was achieving strategic objectives that exceeded their immediate battlefield effectiveness. Corporal James Harris documented the transformation of American tactical procedures in reports that would influence heavy weapons employment for decades following the war’s conclusion.

Marine units equipped with quad 50 weapons developed new coordination procedures that integrated these platforms with conventional infantry and artillery in ways that maximize their psychological impact while minimizing logistical burdens. The weapons had evolved from anti-aircraft platforms into instruments of psychological warfare that achieved victory through the systematic destruction of enemy morale rather than traditional military objectives.

The medical personnel treating Japanese prisoners observed trauma responses that differed qualitatively from wounds inflicted by conventional weapons, suggesting that exposure to quad 50 fire produced psychological damage that persisted long after physical injuries had healed.

Military psychiatrists noted symptoms resembling shell shock, but with characteristics that indicated exposure to sensory experiences that exceeded normal human capacity to process and integrate. These clinical observations contributed to early understanding of what would later be classified as post-traumatic stress disorder.

Though the specific effects of extreme firepower exposure remained poorly understood for decades, Mason’s crew received commendations that recognized their tactical achievements. while carefully avoiding direct acknowledgement of the psychological warfare they had inadvertently conducted. Official reports described the destruction of enemy positions and the capture of strategic objectives, but made no mention of the terror campaigns that had shattered Japanese military morale throughout the operational area. The distinction reflected institutional discomfort with weapons that achieve

victory through means that challenged traditional concepts of honorable warfare and military professionalism. The final Japanese surrender in the sector occurred on February 28th when Sergeant Major Suzuki approached Marine lines leading the remaining members of his command.

87 soldiers who had endured two weeks of psychological pressure that had proven more effective than months of conventional combat operations. Suzuki’s formal statement translated by intelligence officers and preserved in military archives described the experience of commanding troops who had lost the will to resist weapons that made personal courage irrelevant and rendered traditional military training obsolete.

Post-war analysis revealed that the Quad 50 weapons had achieved casualty ratios unprecedented in Pacific warfare, destroying Japanese resistance while sustaining minimal American losses. The second battalion’s operations resulted in over 1500 enemy casualties while suffering fewer than 30 killed and wounded. A tactical exchange that reflected the overwhelming superiority of weapons that could deliver concentrated firepower with precision that exceeded human capacity to resist or evade.

These statistics influenced post-war military planning and contributed to doctrinal developments that emphasized technological superiority over traditional infantry tactics. The legacy of the Luzon campaign extended beyond immediate tactical lessons to fundamental questions about the nature of warfare and the relationship between technology and military effectiveness.

Weapons that had been designed for specific technical purposes had evolved into instruments of psychological dominance that achieve strategic objectives through the systematic destruction of enemy morale rather than conventional military methods. The experience suggested that future conflicts would be determined by technological capabilities rather than traditional military virtues.

A prediction that would prove accurate in subsequent decades as warfare continued to evolve toward increasingly mechanized and impersonal methods of achieving political objectives through the application of overwhelming force that made human courage and determination irrelevant factors in determining battlefield outcomes.

News

CH2 What Japanese Admirals Said When American Carriers Crushed Them at Midway

What Japanese Admirals Said When American Carriers Crushed Them at Midway At 10:25 a.m. on June 4th, 1942, Admiral…

CH2 How a U.S. Sniper’s ‘Car Battery Trick’ Killed 150 Japanese in 7 Days and Saved His Brothers in Arms

How a U.S. Sniper’s ‘Car Battery Trick’ Killed 150 Japanese in 7 Days and Saved His Brothers in Arms …

CH2 German Pilots Were Shocked When P-38 Lightning’s Twin Engines Outran Their Bf 109s

German Pilots Were Shocked When P-38 Lightning’s Twin Engines Outran Their Bf 109s The sky over Tunisia was pale…

CH2 When The Germans Saw The American Jeep Roaming On D-Day – Their Reaction Showed How Doomed Germany Was…

When The Germans Saw The American Jeep Roaming On D-Day – Their Reaction Showed How Doomed Germany Was… June 7th,…

CH2 What Eisenhower Told His Staff When Patton Reached Bastogne First Gave Everyone A Chill

What Eisenhower Told His Staff When Patton Reached Bastogne First Gave Everyone A Chill In the bitter heart of…

CH2 The “Ghost” Shell That Passed Through Tiger Armor Like Paper — German Commanders Were Baffled

The “Ghost” Shell That Passed Through Tiger Armor Like Paper — German Commanders Were Baffled The morning fog hung…

End of content

No more pages to load