Japanese Snipers Were Terrified When They Realized U.S. Marines Can Do This With The 40mm Cannons

At 6:15 on the morning of September 17th, 1944, Captain George Jones pressed his body flat against the rough coral of Peleliu’s shoreline and listened to the eerie silence between rifle shots. The air was heavy with humidity and gunpowder, the acrid tang of both mixing with the salt blowing in from the sea. Overhead, the sun had just begun to burn through the low tropical haze, casting shards of light across a battlefield that felt less like an island and more like the mouth of hell itself. Jones was thirty-one years old, a combat-hardened Marine who had already survived twelve amphibious assaults across the Pacific. He had seen jungles, caves, and firestorms—but nothing like this.

His men were dying, one by one, and he couldn’t even see who was killing them.

For two days, his company had been pinned down just three hundred yards inland from the beachhead. The Japanese snipers—so invisible they seemed more like phantoms than soldiers—had turned the jungle canopy into a killing ground. Shots cracked from above with no warning, no flash, no trace. The bullet would come first, the sound second. The men of Jones’s company had stopped talking, stopped moving except when absolutely necessary. Every rustle of leaves, every flicker of shadow drew their eyes skyward in terror.

He raised his field glasses again and scanned the treetops. Nothing. Only green, endless and blinding under the sun. Somewhere up there, hidden among the branches, men were bound to the trunks of palm trees with rope, their bodies camouflaged with living leaves, their rifles wedged against their shoulders in perfect stillness. The Japanese snipers of Sergeant Major Hiroshi Tanaka’s elite unit had mastered the art of vanishing in plain sight.

In forty-eight hours, Tanaka’s men had killed twenty-three Marines—twenty-three names Jones would have to write in his report later—with not one confirmed enemy casualty in return. The bodies of his riflemen lay in the sand and underbrush where they’d fallen, frozen in grotesque stillness, each death the work of a single unseen shot.

The Japanese strategy was ruthless and brilliantly simple. The snipers didn’t hide behind logs or inside bunkers as they had on earlier islands. They became part of the forest. They lashed themselves into place high above the ground so that, even if mortally wounded, they would not fall from their perch. They fired until death, their bodies held upright by rope, their fingers still near the triggers of their rifles.

Jones gritted his teeth as another crack split the still air. Somewhere to his left, a Marine cursed and dropped. The sound of his helmet hitting coral echoed louder than the shot itself. Jones turned his glasses toward the jungle again, but the sniper was gone—already repositioned, already silent.

His lieutenant, Joseph Walker, crawled up beside him through the sand. Walker’s face was streaked with sweat and grime, his helmet askew. He looked younger than his years, but his eyes carried the same exhaustion that all of them shared. “They’re not fighting the same war we are,” Walker muttered. “We’re looking in the wrong direction, Captain. They’re up there, everywhere.”

Jones didn’t answer. He didn’t need to. The evidence lay scattered all around them—rifles abandoned beside lifeless bodies, helmets punctured clean through, the sand soaked dark beneath them. The Marines had always prided themselves on aggression, on closing with the enemy and overwhelming him with fire and courage. But courage didn’t matter when death came from forty feet above.

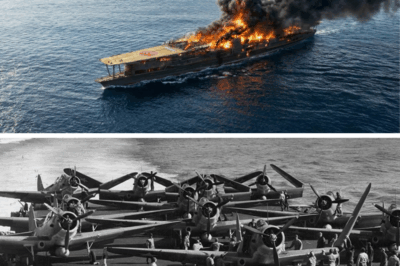

Walker pointed toward the lagoon, where several landing craft still floated just offshore. Mounted on their decks were the squat, double-barreled 40mm Bofors anti-aircraft guns—weapons designed to shoot planes out of the sky, not pick men out of trees. Each gun could fire 120 rounds per minute, each shell containing enough explosive force to turn a palm tree into splinters. “Those guns,” Walker said quietly. “We could use them.”

Jones frowned. The thought was insane—and yet, in that moment, insanity might have been the only thing left that made sense.

Peleliu was supposed to have been another stepping stone in the island-hopping campaign. The planners in Washington had called it “a three-day operation.” They said the island’s capture would secure MacArthur’s flank for the invasion of the Philippines. But those planners had never set foot on its blistering coral ridges or its jungles so dense that light barely touched the ground. They hadn’t seen how the Japanese had transformed every inch of terrain into a fortress.

By the time Jones’s company landed on September 15th, the first wave had already paid in blood for every yard of progress. The beaches were littered with wrecked amphibious tractors and the burned-out hulks of Sherman tanks. The heat rose to 115 degrees in the open sun. The coral cut through boots and flesh alike. Every foot of ground taken cost lives, and yet it wasn’t bunkers or machine guns halting their advance now—it was the trees themselves.

Tanaka’s snipers had studied American tactics since Guadalcanal. They had learned how Marines fought—how they relied on mutual support, overlapping fields of fire, and the momentum of coordinated movement. So Tanaka destroyed those assumptions. His men didn’t defend positions; they defended angles. Every tree became a potential firing point. Every direction became a threat.

The Type 97 sniper rifle they carried was heavy and crude compared to an American Springfield, but in the hands of Tanaka’s men, it was an instrument of terror. Mounted with an 8x scope, it could reach out to four hundred meters—and from the height of a palm tree, that range expanded dramatically. A single sniper could dominate hundreds of yards of terrain, firing down through layers of foliage while remaining invisible.

Jones had watched it happen again and again. A Marine would move, crouched low, hugging the ground. The shot would come from above, from nowhere. The bullet would pass through the canopy, through the man, and into the dirt. Silence would follow.

He had tried every conventional tactic he knew. Rifle volleys, machine gun suppression, mortar fire. None of it worked. The Marines couldn’t see their targets, and firing blindly into the trees wasted ammunition they couldn’t afford to lose. Mortars exploded harmlessly in the canopy, their shrapnel scattering without hitting the snipers bound high in their nests.

By the second day, the men were jumpy, their nerves shredded. Even a bird fluttering from a branch was enough to trigger a flurry of gunfire. Jones could feel the tension coiling tighter with every passing hour. He had to find a solution—and soon—before his company broke completely.

He turned Walker’s suggestion over in his mind. The 40mm Bofors guns had been brought ashore to protect against enemy aircraft. Each shell was designed to explode with devastating force, shredding metal and wings. A single burst could obliterate a palm grove. But using them against snipers? That wasn’t in any field manual.

Jones looked again through his field glasses. He could just make out the outline of the landing craft offshore, the twin barrels of the Bofors glinting faintly in the morning sun. The gunners aboard were idle now; there hadn’t been an air attack since dawn. If those guns could be turned inland…

He set his glasses down and exhaled slowly. The Japanese had forced him into a game he didn’t know how to play. Every instinct drilled into him through years of training told him to respond with precision, with discipline, with control. But the enemy in the trees didn’t care about rules. They had rewritten the battlefield entirely.

The Marines had been trained to outshoot and outmaneuver their opponents. But what if victory now depended not on marksmanship, but on imagination? What if the only way to survive was to turn the tools of another war—the guns meant for skies—against the ghosts in the jungle?

He could still hear the snipers at work, faint cracks echoing through the humid air. Every sound was followed by silence, and in that silence, fear multiplied. The Japanese had learned how to weaponize invisibility.

Walker crouched beside him, waiting for an answer. The lieutenant’s voice was low but urgent. “Sir, we can’t keep trading lives for guesses. We need to hit the whole canopy at once. Burn them out. Shake them down. Those 40mm shells… they’ll do it.”

Jones didn’t reply right away. His mind replayed the past forty-eight hours—the faces of the men he’d lost, the blood in the sand, the eyes of the survivors staring blankly upward. Somewhere beyond that treeline, hidden among the leaves, the enemy was watching too. Watching and waiting, confident that the Marines would continue to fight by the same old rules.

But rules, Jones realized, had their limits.

He wiped the sweat from his brow and looked once more toward the jungle, its green depths rippling under the heat. The morning sun reflected off the rifle barrels of the snipers, just for a moment, like glints of glass. He felt something shift in his gut—a decision taking form before he even spoke it.

The problem, he understood now, wasn’t courage. It wasn’t firepower. It was perspective. The Japanese held the high ground because the Marines were still thinking like infantry. Maybe it was time to start thinking like something else entirely.

Offshore, the 40mm guns waited, silent and ready.

And somewhere deep in the trees, unseen eyes were watching, unaware that for the first time since the landing, the balance of fear was about to change.

Continue below

On the morning of September 17th, 1944, at 06:15, Captain George Jones crouched behind a coral outcrop on the beaches of Pleu, watching his Marines fall one by one to invisible killers hidden in the jungle canopy above. At 31 years old, he was a seasoned company commander with 12 successful island campaigns behind him. But nothing had prepared him for this.

Japanese snipers so well concealed that his men were dying from shots that seemed to come from the trees themselves. In the first 48 hours of the assault, Sergeant Major Hiroshi Tanaka’s elite sniper units had claimed 23 marine lives without a single confirmed enemy casualty.

The Japanese had turned every palm tree into a fortress, every branch into a firing position, binding themselves to their perches with rope so they could shoot until death rather than retreat. Jones watched through his field glasses as another of his riflemen dropped, the crack of the Aasaka Type 99 echoing from somewhere in the green maze ahead. His Marines were pinned down, afraid to move, scanning endlessly upward for muzzle flashes that never came twice from the same spot.

The traditional Marine response, accurate rifle fire and aggressive assault, was useless against enemies who fought from positions 40 ft above the jungle floor. Lieutenant Walker approached with a wild suggestion that morning, pointing to the 40mm Bowfors anti-aircraft guns mounted on their landing craft, still loaded with explosive shells meant for Japanese planes.

The Marine Corps had trained them to shoot snipers with rifles to match precision with precision. But the Japanese had changed the rules. Jones realized his men were dying because they were fighting the wrong war entirely. What the enemy feared most wasn’t another sniper. It was the moment the Marines stopped playing by the old rules altogether.

The morning sun cast long shadows across Paleleu’s coral beaches as Captain George Jones surveyed the killing field his marines had inherited. The first wave had landed at 0800 on September 15th. And now, 2 days later, the advance had ground to a complete halt 300 yd inland. The problem wasn’t the Japanese bunkers.

they had expected or the machine gun nests they had trained to assault. It was the trees themselves that had become weapons. Sergeant Major Hiroshi Tanaka had transformed the jungle canopy into a three-dimensional battlefield that defied every tactical manual the Marines carried. His snipers weren’t simply hidden. They were integrated into the forest ecosystem itself.

Bound to their positions with hemp rope and camouflaged with living branches that made them invisible from below. The Type 97 sniper rifles they carried had an effective range of 400 meters, but Tanaka’s men fired from elevated positions that extended their dominance over the entire Marine Beach head. Jones watched through his field glasses as Lance Corporal Martinez from second squad attempted to move between two palm trees. The shot came from somewhere in the green canopy above.

The distinctive crack of the Arosaka followed by the wet thump of the bullet finding its target. Martinez dropped without a sound. The 23rd Marine to fall to invisible fire since the landing. There had been no muzzle flash, no movement in the trees, no indication of where the shot had originated. The sniper had already shifted position or melted back into his concealment.

The Japanese had learned from earlier island battles that American firepower could overwhelm any fixed position. So they had abandoned the static defense of bunkers and trenches. Instead, Tanaka had created a network of mobile snipers who could strike from any direction and vanish before return fire could be directed against them. Each sniper carried only 20 rounds, but those 20 shots were intended to kill 20 Marines.

The psychological effect was devastating. Jones could see it in his men’s faces as they scanned the canopy above, knowing that death could come from any tree at any moment. Traditional Marine tactics emphasized aggressive assault and overwhelming firepower at the point of contact. But how could they assault an enemy they couldn’t see? How could they concentrate firepower against targets that existed only for the split second it took to pull a trigger? Jones had trained his company to advance under covering fire

from rifle squads and light machine guns, but covering fire was useless when the enemy held the high ground in every direction simultaneously. The Japanese snipers had turned the fundamental assumptions of ground combat upside down.

American infantry doctrine was built on the principle that superior firepower and aggressive movement could overcome any defensive position. The Marines had landed with M1 Garands, Browning automatic rifles, light machine guns, mortars, and the backing of naval artillery. Enough firepower to reduce any Japanese position to rubble. But none of these weapons could effectively engage targets 40 ft above the ground, concealed in dense foliage, firing single shots from unknown positions.

Tanaka’s snipers had studied American tactics during the Guadal Canal and Terawa campaigns. They knew the Marines would advance in squad formations with riflemen providing mutual support while automatic weapons suppressed enemy positions. The Japanese response was to eliminate the assumption of mutual support by making every position a potential firing point.

A Marine rifleman scanning for enemies at ground level would never see the sniper positioned directly above him until it was too late. The elevation advantage gave the Japanese snipers additional benefits beyond concealment. Shooting down at targets eliminated much of the guesswork involved in range estimation.

While the Marines trying to return fire had to shoot nearly straight up through layers of vegetation that absorbed or deflected their bullets. The Arasaka Type 97 could punch through several feet of palm frrons and still retain enough velocity to kill. But the American M1 Garand lost accuracy and stopping power when fired at such steep angles through dense cover.

Lieutenant Joseph Walker had spent the morning studying the problem from a technical perspective. He had positioned himself near the waterline where he could observe the Japanese snipers tactics without exposing his men to additional casualties. What he saw convinced him that conventional infantry weapons were fundamentally inadequate for this type of engagement.

The Marines needed something that could reach the enemy’s elevated positions and deliver enough explosive force to neutralize targets even when they couldn’t be precisely located. The solution was anchored just offshore, mounted on the landing craft that had brought the Marines to Paleu’s beaches.

The 40mm BO4’s anti-aircraft guns had been installed to protect the invasion fleet from Japanese air attacks, but the enemy planes had failed to materialize. Instead, the gun sat idle while Marines died from an enemy that conventional weapons couldn’t reach. Walker approached Jones with his radical proposal just as another Marine fell a sniper fire.

The Bowfor’s guns could fire high explosive shells at a rate of 120 rounds per minute with enough destructive power to shatter entire trees and eliminate any snipers concealed within them. The shells had a blast radius of 10 m, which meant precise target identification was unnecessary. A few rounds into any suspicious tree would either kill the sniper or force him to relocate.

The idea violated everything the Marines had been taught about precision marksmanship and fire discipline. Instead of matching the enemy’s precision with superior accuracy, Walker proposed overwhelming the Japanese with raw destructive power. The 40mm shells would destroy not just the snipers, but the entire environment they used for concealment and protection.

Jones realized that his Marines were losing because they were fighting according to rules that no longer applied. The Japanese had created a new form of warfare that made traditional infantry tactics obsolete, and the only response was to abandon those tactics entirely. The enemy had turned the jungle into a weapon, but the Americans possessed weapons capable of destroying the jungle itself.

The Bowfor’s 40mm autoc cannon represented a complete departure from the precision-based philosophy that had dominated American military thinking since the Revolutionary War. Designed by AB Bowfors in Sweden during the 1930s, the weapon had been intended as an anti-aircraft gun capable of destroying fastmoving targets at ranges up to 4,000 m.

The American version, manufactured under license, could sustain a firing rate of 120 rounds per minute with each shell, weighing nearly 2 lb and carrying enough high explosive to devastate light structures and personnel within a 10- m radius. Lieutenant Walker had studied the technical specifications during his artillery training at Quantico, but he had never considered the weapon’s potential for ground support operations.

The 40mm shell traveled at 850 m/s, making it capable of penetrating light armor or concrete fortifications. More importantly for the current situation, the high explosive rounds were designed to fragment upon impact, creating a lethal spray of metal shards that could clear large areas of vegetation and eliminate multiple targets simultaneously.

The Marines had landed on Paleu with three Bowfors guns mounted on LCM landing craft positioned just offshore. Each gun was operated by a crew of four men, a gunner who aimed and fired the weapon, a loader who fed the clips of ammunition, a trainer who adjusted the weapon’s elevation and traverse, and a commander who coordinated target acquisition and fire control.

The crews had trained extensively in anti-aircraft procedures, learning to track fastmoving targets across the sky and deliver accurate fire at ranges measured in thousands of meters. Walker realized that the same principles could be applied to ground targets, but with significant modifications to the standard operating procedures.

Instead of tracking aircraft across open sky, the gunners would need to concentrate their fire on specific trees or areas of vegetation where snipers were suspected to be hiding. The reduced range would increase accuracy dramatically, while the explosive shells would compensate for the difficulty of precise target identification in dense jungle terrain. The technical challenges were substantial, but not insurmountable.

The Bow Force guns had been designed for high angle fire against aerial targets, which meant they could easily elevate to engage snipers positioned in tall trees. The maximum elevation of 85° would allow the guns to fire almost straight up if necessary, while the traverse capability of 360° meant they could engage targets in any direction from their shipboard positions.

Sergeant John Miller had operated Bowfor’s guns during the earlier campaigns at Terawa and Saipan where they had successfully engaged Japanese aircraft attempting to attack the invasion fleet. He understood the weapons capabilities and limitations better than any other marine in the battalion.

When Walker approached him with the proposal to use the guns against ground targets, Miller immediately grasped both the potential and the risks involved. The ammunition was the critical factor. Each Bowfor’s gun carried 400 rounds of mixed ammunition, armor-piercing shells designed to penetrate aircraft fuselages, high explosive shells intended to destroy lightly armored targets, and tracer rounds for target identification, for ground support, or operations against snipers.

The high explosive shells would be most effective, but the armor-piercing rounds might also prove useful against Japanese positions that included reinforced structures or natural rock formations. Miller calculated that a sustained burst of 10 to 15 rounds could effectively clear any tree of concealed snipers while minimizing ammunition consumption.

At the standard rate of fire, this represented approximately 8 seconds of continuous shooting, long enough to saturate the target area with explosive shells, but short enough to allow rapid shifting between multiple targets. The psychological effect on the Japanese would be as important as the physical destruction.

Since the snipers had relied on their invulnerability to maintain morale and tactical effectiveness, the logistics of coordinating fire support from naval weapons required careful planning and communication procedures. The landing craft carrying the Bowfor’s guns were anchored approximately 300 m offshore, which put them within easy range of the Japanese sniper positions, but also required precise target identification to avoid hitting friendly forces.

Walker worked with Miller to establish a fire control system using radio communication and visual signals that would allow the Marines ashore to direct the guns against specific targets. The standard procedure would involve a forward observer identifying a suspected sniper position and radiating the coordinates to the gun crews offshore.

The Bowfor’s gunner would then traverse and elevate his weapon to engage the target, firing short bursts of high explosive shells until the observer confirmed the position had been neutralized. The entire process from target identification to effective fire could be completed in less than 30 seconds, fast enough to engage snipers before they could relocate to new positions.

Walker recognized that this represented a fundamental shift in the relationship between firepower and precision that had defined infantry combat since the introduction of rifled weapons. Instead of matching the enemy’s accuracy with superior marksmanship, the Marines would overwhelm Japanese positions with explosive force that made precise aim irrelevant.

A single 40mm shell contained enough destructive power to eliminate not just a sniper, but the entire tree that concealed him along with any other enemies positioned nearby. The tactical implications extended beyond the immediate problem of Japanese snipers.

If the Bowfor’s guns proved effective in this role, they could be used to suppress machine gun nests, destroy light fortifications, and clear landing zones for helicopter operations. The weapon’s rapid rate of fire and explosive shells made it ideal for area suppression missions where the exact location of enemy forces was unknown, but their general position could be determined.

Captain Jones approved the experimental use of the Bow Force guns with the understanding that success would depend entirely on the ability of the gun crews to adapt their anti-aircraft training to ground support operations. The technical skills were transferable, but the tactical procedures would have to be developed through trial and error under combat conditions.

The first test would come within hours as Japanese snipers continued to pin down the Marine advance and casualties mounted with each passing hour. The transformation of anti-aircraft weapons into ground support artillery represented more than just tactical innovation. It embodied the American approach to warfare that emphasized technological solutions to tactical problems.

Rather than accepting the constraints imposed by enemy tactics, the Marines would use superior firepower to change the fundamental conditions of the battlefield itself. The first test came at 14:30 on September 18th when Private First Class Rodriguez from third squad was shot while attempting to retrieve ammunition from a supply drop 40 m in land from the beach.

The sniper’s bullet had come from a massive breadfruit tree that rose 60 ft above the jungle floor. Its thick canopy providing perfect concealment for Corporal Masaru Yoshida’s carefully prepared position. Lieutenant Walker immediately radioed the coordinates to Sergeant Miller aboard LCM7, anchoring 320 m offshore with its bow force gun trained toward the suspected target area.

Miller adjusted the gun’s elevation to 45° and traverse left until the bread fruit tree appeared in his optical sight. The range was well within the weapon’s capabilities, but engaging a stationary ground target required different techniques than tracking fast-moving aircraft. He selected high explosive ammunition and prepared to fire a three round burst that would saturate the target area with fragmentation while conserving shells for additional engagements.

The first 40mm round struck the trunk of the breadfruit tree 18 ft above ground level, detonating on impact and sending a shower of wood splinters and metal fragments through the surrounding vegetation. The explosion was far louder than the crack of Japanese rifle fire. A deep thunderous boom that echoed across the entire beach head.

The second shell hit higher in the canopy, shredding branches and leaves in a cascade of debris that rained down on the marines below. The third round exploded among the upper branches where Yosha had positioned himself. The blast wave and fragmentation eliminating the sniper instantly while destroying his concealment. Captain Jones observed the results through his field glasses, watching as the massive tree swayed and partially collapsed under the explosive impacts.

Where Japanese snipers had previously been invisible and invulnerable, the Bowfor’s gun had created a zone of total destruction that extended 15 m in every direction from the target tree. Any enemy positioned within that area would have been killed or severely wounded by the overlapping blast effects of the three shells.

The psychological impact on both sides was immediate and profound. The Marines, who had been pinned down by sniper fire for two days, suddenly realized they possessed a weapon capable of reaching their tormentors. The thunderous explosions and spectacular destruction of the breadfruit tree demonstrated that the Japanese advantage in concealment could be neutralized by overwhelming firepower.

Morale improved visibly as Marines began to advance with renewed confidence, knowing that effective fire support was available at radio call. For the Japanese defenders, the implications were equally clear, but far more ominous. Sergeant Major Tanaka’s carefully constructed sniper network depended on the invulnerability of elevated positions that conventional infantry weapons could not effectively engage.

The Bowfor’s bombardment had shattered that assumption in less than 30 seconds, proving that no tree or natural formation could provide adequate protection against high explosive artillery fire. Word of the successful engagement spread rapidly through both the American and Japanese forces on Paleu. Marine forward observers began identifying additional suspected sniper positions and calling in fire missions from the offshore bowor’s guns.

The weapons proved devastatingly effective against targets that had previously been immune to groundbased fires, systematically destroying the concealed positions that Tanaka had spent months preparing. The tactical procedures evolved rapidly as gun crews gained experience with ground support operations.

Miller developed a technique of firing single rounds at suspected positions, observing the results, then following up with additional shells if movement or return fire indicated the presence of surviving enemies. This method conserved ammunition while ensuring thorough neutralization of each target area. By 1700 hours on September 18th, the three Bowfors guns had engaged 47 suspected sniper positions, expending 230 rounds of mixed high explosive and armor-piercing ammunition.

The results were measured not only in confirmed enemy casualties, but in the complete suppression of Japanese sniper activity along the entire beach head. Marines were able to advance inland for the first time since landing, moving through areas that had been death traps just hours earlier.

The Japanese response revealed the extent to which their defensive plan had depended on sniper harassment of American forces. With their elevated firing position systematically destroyed by artillery fire, the remaining snipers were forced to relocate to ground level positions that offered far less tactical advantage. Many abandoned their missions entirely, falling back to secondary defensive lines deeper inland, where they hoped to find better protection from the devastating 40mm bombardments.

Tanaka himself had witnessed the destruction of six sniper positions from his command post in a reinforced cave on Paleu’s central ridge. The methodical elimination of his most experienced marksmen represented a catastrophic failure of the defensive strategy he had developed over 18 months of preparation.

The Americans had not only neutralized his snipers, but had done so with such overwhelming force that the psychological effect extended far beyond the immediate tactical situation. The effectiveness of the Bowforce guns against ground targets prompted immediate tactical adjustments throughout the Marine Corps forces on Pleu.

Additional landing craft were positioned to provide overlapping fields of fire, while forward observer teams were reorganized to coordinate multiple fire missions simultaneously. The weapons that had been intended as a last resort against Japanese air attacks had become the primary means of suppressing enemy ground forces.

Lieutenant Walker coordinated with artillery specialists from the First Marine Division to develop standardized procedures for naval gunfire support using the 40mm weapons. The techniques pioneered during the first day of operations were refined and documented for use in subsequent island campaigns, transforming an improvised solution into established doctrine.

The success at Paleu demonstrated that technological innovation could overcome even the most sophisticated enemy tactics when applied with proper coordination and tactical flexibility. The Japanese had created a nearly perfect defensive system based on concealment and precision marksmanship, but they had failed to account for the American ability to deploy overwhelming firepower against any target, regardless of its apparent invulnerability.

Miller’s gun crews reported complete suppression of sniper activity in their assigned sectors by nightfall on September 18th. The trees that had sheltered Japanese marksmen throughout the day were reduced to splintered stumps and debris fields, while the snipers themselves had either been eliminated or forced to abandon their positions.

The Marines had achieved in hours what conventional tactics had failed to accomplish in days of costly frontal assaults. The dawn of September 19th revealed the catastrophic scope of the previous day’s artillery bombardment to the surviving Japanese defenders scattered across Pleu’s shattered landscape. Sergeant Major Tanaka emerged from his command bunker to survey what remained of his carefully constructed sniper network, finding nothing but splintered tree stumps and cratermarked earth where his most experienced marksmen had once held impregnable positions. Of the 63 elite snipers he had positioned throughout the

beach head defenses, only 17 had reported to secondary rally points during the night, and most of those carried wounds from shell fragments or falling debris. The psychological impact of the Bowfor’s bombardment extended far beyond the immediate tactical losses. Tanaka’s snipers had been selected and trained over 18 months of intensive preparation, each man chosen for his exceptional marksmanship skills and psychological resilience under combat stress. They had endured the brutal fighting at Guadal Canal and Tarawa,

maintaining their effectiveness even as conventional Japanese forces collapsed around them. The systematic destruction of their positions by American artillery represented not just tactical defeat, but the collapse of their fundamental assumptions about warfare itself.

Private Kenji Nakamura, one of the few survivors from the coastal sniper teams, described the experience to his sergeant as unlike anything he had witnessed during three years of Pacific combat. The Japanese had grown accustomed to American superiority and conventional firepower, accepting that their bunkers and fortified positions would eventually be reduced by naval bombardment or aerial attack.

But the snipers had operated under the assumption that their individual concealment and mobility made them immune to such massive retaliation. The precision with which the Bowfor’s guns had targeted specific trees and eliminated individual marksmen suggested that the Americans possessed both the technical capability and tactical flexibility to neutralize any Japanese defensive innovation.

Tanaka convened his surviving unit commanders at 0400 to assess the situation and develop new defensive procedures. The meeting took place in a natural cave system on Paleu’s central ridge, chosen because its overhead protection made it immune to the flat trajectory fire of the offshore artillery.

The discussion revealed the extent to which Japanese tactics had been built around assumptions that no longer applied to the current battlefield environment. The original defensive plan had called for snipers to operate from elevated positions that maximized their fields of fire while minimizing exposure to return fire from groundbased weapons.

The strategy had proved devastatingly effective against marine infantry armed with rifles and light machine guns, inflicting casualties at ranges that made accurate return fire virtually impossible. The introduction of explosive artillery capable of reaching any elevated position had eliminated the fundamental advantage on which the entire system depended.

Lieutenant Hiroshi Watanabe, commanding the reserve sniper detachment, proposed relocating the remaining marksmen to ground level positions that offered natural protection from artillery fire. Caves, rock formations, and reinforced structures could provide overhead cover that trees and vegetation could not, potentially allowing snipers to continue operations despite the American firepower advantage.

However, such positions would severely limit fields of fire and reduce the snipers ability to engage targets across the broad frontages they had previously dominated. The tactical dilemma facing the Japanese defenders reflected a larger strategic problem that had plagued their Pacific campaigns since 1942. American industrial capacity allowed them to deploy overwhelming quantities of advanced weaponry against any defensive system the Japanese could devise.

When one tactical innovation proved effective, the Americans responded with new technologies and procedures that neutralized the advantage within weeks or months. The Japanese were trapped in a cycle of tactical adaptation that they could not win because their opponents possessed both superior resources and superior flexibility.

Tanaka recognized that his sniper units could no longer function as an independent arm capable of disrupting American operations through precision marksmanship. The survivors would have to be integrated into conventional defensive positions where their specialized skills could support broader tactical objectives rather than operating as autonomous units.

This represented a fundamental shift away from the elite sniper doctrine that had defined Japanese defensive strategy throughout the Pacific theater. The psychological effect of this tactical retreat extended throughout the Japanese garrison on Pleu. The sniper units had represented the most successful aspect of Japanese defensive operations.

The one area where individual skill and tactical innovation had consistently overcome American advantages in firepower and technology. Their systematic elimination by artillery fire demonstrated that no Japanese tactical innovation could survive sustained contact with American problem-solving capabilities.

Colonel Kuno Nakagawa, commanding the Paleo garrison, received Tanaka’s report at 0600 and immediately understood the broader implications. The failure of the sniper network meant that his defensive strategy would have to rely entirely on conventional fortifications and prepared positions that American forces had repeatedly proven capable of reducing through sustained bombardment.

The Japanese no longer possessed any tactical advantages that could compensate for their overwhelming disadvantages in firepower and logistical support. The emotional impact on the surviving snipers was equally devastating. Men who had considered themselves the elite of the Imperial Japanese Army, capable of holding entire enemy units at bay through superior marksmanship and fieldcraft, found themselves reduced to ordinary infantrymen hiding in caves and bunkers.

The pride and confidence that had sustained them through previous campaigns evaporated as they realized that their specialized skills were no longer relevant to the tactical situation they faced. Corporal Yoshida’s death had been witnessed by three other snipers positioned in adjacent trees, all of whom described the same sequence of events, the thunderous explosions, the complete destruction of the target area, and the impossibility of survival for anyone caught within the blast radius. The 40mm shells had not merely killed Yoshida, but had obliterated

every trace of his position, leaving nothing but splinters and cratermarked earth, where an expert marksman had once commanded a 300 meter sector of the beach head. The tactical modifications implemented by the remaining Japanese forces reflected their understanding that the Americans had fundamentally altered the conditions of the battlefield.

Snipers were withdrawn from all elevated positions and reassigned to support roles within heavily fortified bunkers. Individual marksmanship training was deemphasized in favor of collective defense procedures designed to maximize casualties among attacking forces rather than disrupting their operations through precision fire. By midday on September 19th, the transformation of Japanese defensive tactics was complete.

The elite sniper units that had terrorized American forces during the initial landing phases had been eliminated as an effective fighting force. Their specialized skills rendered obsolete by artillery innovations they could not counter or survive. The psychological blow to Japanese morale was compounded by the realization that their most successful tactical innovations were no match for American technological superiority and tactical flexibility.

The success of the Bowfor’s guns at Pleu reached Marine Corps headquarters at Pearl Harbor within 48 hours of the first engagement carried by coded radio transmissions that described the complete suppression of Japanese sniper activity through innovative use of anti-aircraft weapons in ground support roles.

Major General Roy Guyger, commanding the Third Amphibious Corps, immediately recognized the broader implications of Captain Jones’s tactical innovation and ordered detailed afteraction reports from all units involved in the operation. Lieutenant Walker’s comprehensive analysis of the engagement procedures reached Washington by October 1st, 1944, where it was studied by artillery specialists at the Marine Corps schools in Quantico.

The report documented not only the technical specifications and tactical employment of the 40mm guns, but also the psychological effects on both American and Japanese forces. The systematic destruction of elevated sniper positions had fundamentally altered the tactical balance on Paleo, transforming what had been a costly stalemate into a decisive American advance.

The strategic significance of the innovation extended far beyond the immediate tactical success. Marine Corps planners recognized that future Pacific operations would inevitably encounter similar defensive strategies as the Japanese refined their tactics based on lessons learned during earlier campaigns. The ability to neutralize elevated sniper positions with explosive artillery fire represented a permanent solution to a problem that had caused significant casualties during previous amphibious assaults.

Sergeant Miller’s detailed technical recommendations for adapting anti-aircraft weapons to ground support operations were incorporated into revised training curricula at artillery schools throughout the Pacific theater. Gun crews were retrained in target identification procedures that emphasized rapid engagement of suspected sniper positions rather than precise tracking of aerial targets.

The modifications required minimal changes to existing equipment, but demanded entirely new approaches to fire control and ammunition management. The logistical implications of the tactical innovation were equally significant.

Standard ammunition loadouts for Bowour’s guns had been calculated based on anti-aircraft requirements with emphasis on armor-piercing shells designed to penetrate aircraft fuselages and engines. Ground support operations require different ammunition mixes with high explosive shells proving most effective against personnel and light fortifications hidden in vegetation. Supply officers throughout the Pacific Fleet were ordered to adjust their procurement and distribution procedures to support the new tactical requirements.

Captain Jones received promotion to major and assignment to Marine Corps headquarters in Washington where he worked with tactical development specialists to create standardized procedures for naval gunfire support using 40mm weapons. His experiences at Pleu provided the foundation for doctrine that would be applied throughout the remaining Pacific campaigns from Eoima to Okinawa.

The improvised solution that had saved his company became established procedure for the entire Marine Corps. The psychological impact on American forces extended throughout the Pacific theater as word of the Pelleu success spread among combat units preparing for future operations.

Marines who had previously accepted heavy casualties from Japanese snipers as an unavoidable cost of amphibious warfare now understood that effective counter measures existed. Morale improved significantly as units trained in the new procedures and prepared for operations where they would possess decisive advantages over enemy snipers. The Japanese response to the tactical defeat at Pleu revealed the broader strategic challenges facing their Pacific defense strategy.

Intelligence reports captured during subsequent operations showed that Japanese commanders had recognized the fundamental vulnerability of elevated sniper positions to explosive artillery fire. Defensive plans for remaining strongholds were modified to emphasize underground fortifications and cave systems that could provide protection from naval bombardment while still allowing effective defensive fire.

The technical success of the Bowfor’s adaptation prompted development of specialized ground support variants designed specifically for anti-personnel operations in jungle terrain. Engineers at Aberdine proving ground worked with combat veterans to create improved ammunition types, enhanced optical sites, and modified gun mounts that maximized effectiveness against ground targets while retaining anti-aircraft capability.

These improvements were integrated into production lines by early 1945, ensuring that future operations would benefit from weapons designed for dual role missions. Lieutenant Walker’s promotion to captain and assignment to the artillery development board reflected the Marine Corps’s recognition that tactical innovation required systematic institutional support.

His work at Paleo had demonstrated the importance of technical expertise in identifying solutions to battlefield problems, leading to expanded training programs that emphasized creative application of existing weapons to new tactical challenges.

The broader implications of the Paleo innovation extended beyond military applications to influence post-war development of ground support aircraft and helicopter gunships. The principle of using rapid fire explosive weapons to suppress area targets rather than engaging individual enemies with precision fire became a cornerstone of closeair support doctrine during the Korean and Vietnam conflicts.

The tactical flexibility demonstrated by the Marine Corps at Pleu established precedence for military innovation that continued to influence American military doctrine decades later. Sergeant Miller’s technical expertise with the Bowforce system led to his selection for the newly created position of heavy weapons specialist at the Marine Corps schools, where he trained successive generations of artillery officers in the procedures developed during the Pleu operation.

His firstand experience with the tactical employment of anti-aircraft weapons in ground roles provided invaluable insights that could not be replicated through classroom instruction or theoretical study. The strategic success of the innovation was measured not only in reduced American casualties, but in the complete transformation of Japanese defensive tactics throughout the Pacific.

Intelligence analyses conducted after the war revealed that the systematic destruction of sniper networks at Paleu had forced Japanese commanders to abandon their most effective defensive strategy, contributing to the accelerated collapse of resistance during subsequent operations. The legacy of Captain Jones’s tactical innovation extended into the post-war period as military historians and tactical analysts studied the Pleu engagement as an example of battlefield adaptation under combat conditions. The rapid identification of a tactical problem, development of an innovative

solution using available resources and systematic implementation of new procedures became a model for military innovation that influenced training and doctrine development throughout the American armed forces. The transformation of anti-aircraft weapons into ground support artillery represented more than tactical adaptation.

It embodied the fundamental American approach to warfare that emphasized technological solutions to tactical challenges and the systematic application of overwhelming firepower to achieve decisive results with minimal casualties. Peace.

News

CH2 What Churchill Said When Patton Won the Race to Messina Should Be Noted Down In History

What Churchill Said When Patton Won the Race to Messina Should Be Noted Down In History In the spring…

CH2 Japan Rigged Their Own War Games To Win – But Then Lost Exactly Like The Dice Predicted

Japan Rigged Their Own War Games To Win – But Then Lost Exactly Like The Dice Predicted At precisely…

CH2 Wehrmacht Major Fled the Eastern Front — 79 Years Later, His Buried Field Chest Was Found in Poland

Wehrmacht Major Fled the Eastern Front — 79 Years Later, His Buried Field Chest Was Found in Poland It…

CH2 Why German Infantry Feared the 101st Airborne More Than Any Other Division

Why German Infantry Feared the 101st Airborne More Than Any Other Division June 6th, 1944. 02:15 hours. Sainte-Mère-Église, Normandy….

CH2 How One Woman Exposed the Hidden Gun That Shot Down 28 Planes in 72 Hours at Iwo Jima

How One Woman Exposed the Hidden Gun That Shot Down 28 Planes in 72 Hours at Iwo Jima February…

CH2 The 96 Hour Nightmare That Destroyed Germany’s Elite Panzer Division

The 96 Hour Nightmare That Destroyed Germany’s Elite Panzer Division July 25th, 1944. 0850 hours. General Leutnant Fritz Berlin…

End of content

No more pages to load