Japanese Air Force Underestimated The US – They Was Utterly Stunned by America’s Deadly P-38 Lightning Strikes

The morning air over the Solomon Islands shimmered with heat and salt as Lieutenant Commander Hiroshi Nishawa adjusted the leather strap of his flight goggles and scanned the horizon from his cockpit. It was December 27, 1942, and the sunlight poured through breaks in the cloud deck, gleaming against the ocean below. The emerald coastline of Guadalcanal stretched beneath him like a living scar—its jungle canopy cut through by the long white strip of Henderson Field, the American airbase that had refused to die.

He flexed his gloved hands on the control stick of his Mitsubishi A6M Zero, the fighter aircraft that for more than a year had been the terror of the Pacific. The Zero was light, responsive, elegant in flight—an extension of the pilot’s body and mind. In his 200-plus combat missions, Nishawa had outmaneuvered every American aircraft that dared to face him. He knew their weaknesses intimately. The P-39 Airacobra was heavy and clumsy. The P-40 Warhawk could dive fast, but it couldn’t turn to save its life. Against the Zero, they were prey—predictable, desperate, and always too slow.

But today, something was wrong. The radio crackled to life, the chatter from his fellow pilots laced with unease. Reports had been coming in for weeks now—scattered accounts of a new kind of American aircraft. Pilots from Rabaul and Bougainville swore they’d seen them, strange twin-engine fighters that didn’t belong to any known design. Most Japanese officers dismissed those reports as errors—confusion in the chaos of battle. A twin-engine fighter made no sense. Two engines meant weight. Weight meant lost agility. And agility was everything.

Still, the rumors persisted, whispered late at night in mess tents. Futago no hikōki. The twin airplane.

Nishawa pushed the thought aside as he led his eight-plane formation south over the dense jungle. The sunlight flashed off the waves below, and far beneath them, he could see the telltale glint of American planes beginning to take off from the coral strip at Henderson Field. His lips curled slightly in contempt. P-39s and P-40s again. He knew how to handle those. He had memorized their climb rates, their turning radii, their vulnerabilities.

He glanced at his instrument panel—fuel steady, altitude twelve thousand feet. Everything felt routine. And yet, the back of his neck prickled.

Then he saw them.

At first, they didn’t make sense. Against the bright horizon, they appeared almost alien—long twin booms stretching back from a central cockpit, twin engines with propellers spinning in opposite directions. It looked like someone had taken two aircraft and welded them together. The configuration defied logic, defied every principle of fighter design that Japanese engineers held sacred.

“What in the name of—” Nishawa muttered, his voice muffled by his oxygen mask. “Nan da kore wa? What is this thing?”

The American aircraft—there were at least six—were climbing fast, impossibly fast. Their formation was tight, precise, confident. The glint of sunlight off polished aluminum was so intense it seemed almost to burn. For a moment, Nishawa thought they must be interceptors protecting bombers, but there were no bombers in sight. Just these strange, twin-tailed creatures, rising on twin columns of power.

His wingman’s voice came over the radio, sharp and panicked. “Futago no hikōki! Twin aircraft! What are they?”

The words barely left the radio before one of the silver planes rolled gracefully and began to climb almost vertically. No piston-engine fighter should have been able to climb like that—not at this altitude, not with that speed. The Japanese formation tightened instinctively, Zeros banking into defensive positions.

And then, before he could fully comprehend what he was seeing, the enemy closed the distance.

6,000 miles away, two days earlier, in a canvas operations tent on a sweltering airstrip in New Guinea, Captain Tom Lynch of the U.S. Army Air Forces had been pacing in front of a group of young pilots. A hand-drawn map of Guadalcanal hung behind him, marked with arrows and grease-pencil notes. The smell of sweat, oil, and damp paper filled the air.

“Gentlemen,” Lynch said, tapping the map with his pointer, “we’re about to introduce the Japanese to something they’ve never seen before.”

The eighteen pilots of the 39th Fighter Squadron listened in silence. Their khaki shirts were dark with humidity, their faces drawn and tired from weeks of preparation. Outside, the hum of generators mingled with the distant roar of engines being tested.

For over a year, the Japanese Zero had dominated the skies. Its pilots were veterans, many with hundreds of hours of combat experience. Their planes were lighter, faster at low altitudes, and devastating in a dogfight. American pilots had paid dearly to learn their tactics. The P-39s and P-40s were tough machines, but they couldn’t keep up. The only way to survive against a Zero was to dive, run, and pray.

But now, the U.S. had something new.

Lynch’s voice grew steady and deliberate. “The Zero can out-turn you, but it can’t out-climb you. It can’t out-dive you. And it sure as hell can’t outrun you.” He turned to the diagram of the new aircraft tacked beside the map—a sleek twin-engine fighter with a long central fuselage and twin booms. “Boys, meet your new partner in crime—the Lockheed P-38 Lightning.”

The pilots leaned forward. Some had seen the prototypes, others had only heard rumors. Two engines. Twin turbo-superchargers. Four .50-caliber Browning machine guns and a 20mm cannon—all mounted in the nose, firing straight ahead without convergence issues. It looked like something out of a science fiction comic, but its numbers were no fantasy.

Top speed: 414 miles per hour. Combat range: 1,300 miles. Climb rate: 4,000 feet per minute.

The P-38 was the first American fighter designed to combine long range, heavy firepower, and blistering speed. It wasn’t elegant like the Zero—it was a brute-force solution born from American industry’s relentless practicality. The Japanese built their fighters like samurai swords: light, precise, fragile. The Americans built theirs like sledgehammers.

Second Lieutenant Rex Lamb, just twenty-two, shifted nervously in his chair. He had logged barely seventy flight hours in the Lightning, and the thought of facing Japan’s elite airmen in a plane so unlike anything else made his stomach twist. But there was electricity in the room. Beneath the fear was excitement—the raw, reckless energy of men about to test something unproven.

Staff Sergeant Mike Benson, Lynch’s crew chief, leaned in the tent’s doorway, watching them. Years later, he would describe their expressions with a mix of pride and sorrow. “They looked like kids on Christmas morning,” he said. “Kids who just realized Santa brought them a rocket—and that they might die learning how to fly it.”

The technical talk continued for another hour—engine management, power curves, gunnery tactics, and formation flying. But Lynch’s closing words were the ones they remembered most. “The Japanese think they own the sky,” he said. “They think we can’t touch them. Tomorrow, we prove them wrong.”

Now, two days later, that promise was about to be tested.

Nishawa’s eyes darted across the sky as the enemy formation tightened. The twin-engine fighters were not just climbing—they were climbing toward him. No hesitation, no defensive circling, just straight, deliberate aggression. It was behavior he’d never seen from Americans before.

“They’re coming straight at us!” his wingman shouted.

“Hold formation!” Nishawa snapped. “Let them come!”

He felt his heart hammering as the distance closed. The enemy aircraft glinted like liquid silver in the sun, the blue star-and-bar insignia clear now against their sides. He could see the shape of their propellers—counter-rotating, slicing the air in perfect synchronization.

As they approached head-on, Nishawa’s mind raced through every tactic he knew. Head-on attacks were suicide for single-engine fighters. The Zero’s guns were mounted in the wings; to hit anything, he had to aim perfectly, fire early, and hope the convergence point struck true. But these new aircraft… all their guns were in the nose. Every bullet would go exactly where their pilots aimed.

For the first time in his long combat career, Lieutenant Commander Hiroshi Nishawa felt something unfamiliar tightening in his chest—not anger, not adrenaline.

It was dread.

He gritted his teeth and pushed the throttle forward, the roar of his Sakae engine filling the cockpit as he prepared to meet this new enemy head-on. The radio was alive with frantic voices, each one a mix of disbelief and confusion.

“Kare-ra wa hayai! They’re fast!” someone yelled. “Too fast!”

Nishawa didn’t respond. His eyes locked on the approaching formation.

Six silvery shapes in perfect symmetry. Two engines each. The future of American air power, streaking toward him out of the dawn.

And as the distance closed, as the sunlight flared off their wings, he realized with a shiver that everything he thought he knew about air combat—every law of speed, maneuverability, and range—was about to change forever.

Continue below

The morning sun burns through the humid Solomon Islands air as Lieutenant Commander Hiroshi Nishawa adjusts his goggles and grips the control stick of his Mitsubishi A6M0. December 27th, 1942. Henderson Field lies below like a scar on Guadal Canal’s green jungle. American bombers and fighters scattered across the coral runway like sleeping metal birds.

For 16 months, Nishawa and his fellow pilots have owned these skies. The zero rising to them has been their sword of the heavens, outmaneuvering every American fighter thrown against them. Wildcats, war hawks, era cobras, all have fallen to the zero’s legendary agility and the skill of Japan’s elite naval aviators.

But something feels different today. His radio crackles with the voices of his squadron mates, their usual pre-combat banter tinged with an unusual tension. Intelligence reports have been strange. Fragmentaryary accounts of new American aircraft, twin engineed fighters. The descriptions make no sense.

Why would the Americans put two engines on a fighter? It violates everything they know about aerial combat. Nanisur. What is that? The question has been haunting Japanese pilot ready rooms for weeks, whispered in fragments from pilots who claimed to have seen something impossible over the northern Solomons. Nishawa banks his zero into position, leading his formation of eight aircraft toward Henderson Field.

Below the familiar sight of American P39 Aracobras and P40 Warhawks begins their takeoff role. These aircraft he knows. These aircraft he can defeat. The P40’s bulky frame and poor climb rate. The P39’s dangerous spin characteristics and underwhelming performance above 15,000 ft. But today, something else is climbing from Henderson Field.

At first, it looks wrong, like someone has attached two separate aircraft together. Twin booms stretch back from a central cockpit in a cell, each boom terminating in a vertical tail. Twin engines, twin propellers spinning in opposite directions. The design defies logic, defies everything Nishawa has learned about fighter aircraft in his 200 plus combat missions.

Nandanda Cororewa,” he mutters into his oxygen mask. “What the hell is this?” The formation of strange aircraft climbs with shocking speed, their twin engines hauling them upward at a rate that makes Nishawa’s zero, his nimble, lightweight Zero, look sluggish by comparison. More disturbing still, they’re climbing straight toward his formation’s altitude with an aggressiveness that suggests their pilots aren’t afraid.

They should be afraid. Every American pilot should fear the zero by now. But these twin boomed monsters keep climbing. And Nishawa realizes with growing unease that for the first time in his combat career, he’s looking at something completely unknown, something that might change everything. The radio erupts with excited Japanese voices. Futago nohikoki. Twin aircraft.

Naniuru. What do we do? What indeed? How do you fight something you’ve never seen before? 6,000 m away and 2 days earlier, Captain Tom Lynch of the 39th Fighter Squadron, 347th Fighter Group, had been briefing his P38 pilots in a humid New Guinea tent. Maps of Guadal Canal covered a folding table. Aerial reconnaissance photos scattered like puzzle pieces showing Henderson Field and the surrounding Japanese positions.

“Gentlemen,” Lynch had said, his voice carrying the weight of months of preparation. “Were about to introduce the Japanese to something they’ve never seen before.” “The 18 P38 Lightning pilots gathered around the table represented the culmination of two years of desperate American innovation. While Japanese zeros had been shooting down American fighters with impunity across the Pacific, Lockheed’s engineers had been working frantically to create an answer, a twin engine fighter that could match Japanese performance while

leveraging American industrial advantages. Second Lieutenant Rex Lamb, barely 22 and fresh from flight training, had stared at the intelligence photos with a mixture of excitement and terror. The briefing materials painted a sobering picture. Japanese pilots with hundreds of combat hours flying the most maneuverable fighter aircraft in the world over terrain they knew intimately.

The Zero has advantages, Lynch continued, pointing to comparative performance charts. It can turn inside anything we’ve got. It can climb like a homesick angel at low altitude. And their pilots, don’t underestimate their pilots. They’ve been fighting for four years, some of them since China. But then Lynch had smiled, and the expression carried a predatory satisfaction that sent shivers through the assembled airmen.

However, gentlemen, they’ve never seen a P38. They don’t know about our speed advantage, 83 mph faster in level flight. They don’t know about our climb rate above 20,000 ft. They don’t know about concentrated nose arament. Four 50 caliber machine guns and one 20mm cannon all firing straight ahead instead of converging from the wings.

Staff Sergeant Mike Benson, Lynch’s crew chief, had been listening from the tent entrance. Later, he would describe the pilot’s faces during that briefing. like kids on Christmas morning who just found out what was under the tree, but also scared as hell they might not live to play with their presents. The technical advantages were impressive on paper.

Twin Allison V17, 10 engines producing 1,475 horsepower each. Counterrotating propellers eliminating torque effects. Turbo superchargers maintaining power at altitude. a top speed of 414 miles per hour, faster than any production fighter in the world. But statistics meant nothing until they faced the legendary Japanese pilots who had humiliated American air power from Pearl Harbor to the Philippines to Java.

Now climbing over Guadal Canal on December 27th, those theoretical advantages were about to face their ultimate test. Rex Lamb’s hands were slick with sweat inside his leather gloves as he maintained formation on Lynch’s wing. Through his canopy, he could see the approaching Japanese formation.

Eight zeros in perfect V formation. Their pilots confident enough to maintain textbook positioning even with enemy fighters climbing to meet them. That confidence unnerved him. These weren’t green pilots flying inferior aircraft. These were the men who had destroyed American air power across half the Pacific Ocean. But then Lamb looked at his instrument panel and felt a surge of hope.

His airspeed indicator showed 380 mph in the climb, faster than a Zero’s maximum level flight speed. His altimeter was passing through 22,000 ft where the P38’s turbo superchargers gave him a decisive advantage over the naturally aspirated Zero engines. Captain Lynch’s voice crackled through the radio. Bandits 11:00 high. 8 Z probably from Rabal.

Remember your training. Speed is life. Altitude is life insurance. Don’t dogfight them. Use your advantages. The Japanese formation was close enough now that individual aircraft details were visible. Lamb could see the distinctive greenhouse canopies, the fixed landing gear legs, the rising sun markings on wings and fuselage.

Beautiful aircraft, he had to admit. Elegant in their simplicity, but also suddenly shockingly obsolete. Lieutenant Nishawa’s zero formation was maintaining 25,000 ft when the impossible happened. The twin boomed American fighters, whatever they were, kept climbing past zero service ceiling, kept accelerating past zero maximum speed, and arranged themselves in a perfect attack position with an ease that defied everything Nishawa knew about aerial combat.

His radio erupted with confused Japanese voices. Hayi fast taku no they’re climbing high do tataka how do we fight them for the first time in his combat career Hiroshi Nishiaawa realized he was facing aircraft that were simply better than his zero not better flown not better positioned just better Americans had finally built fighters that could outperform the legendary zero in speed climb and altitude capability.

The twin boomed fighters were positioning for an attack and there was nothing his formation could do to prevent it. The Americans held every tactical advantage, altitude, speed, position, and initiative. Nishawa’s hands tightened on his control stick as he prepared for combat unlike anything he’d experienced in 200 previous missions.

The age of zero supremacy was about to end. The first pass happens in seconds, but those seconds rewrite the rules of Pacific air combat forever. Captain Lynch rolls his P38 into a dive from 27,000 ft. His twin Allison engines screaming as the Lightning accelerates past 450 mph. Behind him, 17 more P38s follow in perfect echelon formation.

Their twin booms cutting through the thin air like metallic lightning bolts. Lieutenant Nishazawa sees them coming and reacts with the instincts of a veteran pilot. He throws his zero into a hard left turn. The classic defensive maneuver that has saved his life dozens of times. The Zero responds instantly. It’s legendary agility, allowing a turn radius that should make any attacking fighter overshoot.

But Lynch doesn’t overshoot. He doesn’t even try to turn. Instead, the P38 dives through the Japanese formation at a speed so tremendous that Nishawa’s eyes can barely track the twin boommed shape as it flashes past. Lynch’s concentrated nose armament, 450 caliber machine guns and one 20 mm cannon erupts in a stream of tracers that converge on zero tail number AI 154.

The difference is immediate and devastating. Instead of wing-mounted guns with complex convergence patterns, the P38’s nosemounted weapons fire straight ahead with precision that seems almost surgical. 0 AI154 simply disintegrates. Its lightweight construction no match for the concentrated firepower. Cuso Nishawa curses as his wingman’s aircraft explodes in a ball of orange flame and aluminum fragments.

But there’s no time to mourn. Another P38 is already diving through their formation. Lieutenant Rex Lamb’s first combat engagement unfolds like a fever dream. His P38 screams down through the Japanese formation. Airspeed indicator needle pushing past 480 mph. He selects a zero and squeezes the trigger. Feeling the aircraft shutter as all five weapons discharge simultaneously.

The Japanese pilot tries to evade, throwing his zero into a violent barrel roll. But at this speed, differential evasion is impossible. Lamb’s tracers rake the zero from propeller to tail, and the beautiful, elegant fighter aircraft crumples like paper in a hurricane. But what shocks Lamb most isn’t the easy kill.

It’s what happens next. Instead of being trapped in a turning fight with the remaining zeros, he simply flies away. His P38 speed advantage is so overwhelming that the Japanese fighters can’t pursue. They can’t catch him. They can only watch helplessly as he climbs back to altitude for another attack. For veteran Japanese pilots accustomed to turning dog fights where superior agility meant victory, this is psychological warfare as much as aerial combat.

Their primary advantage, maneuverability, has been rendered irrelevant by sheer speed. Lieutenant Commander Nishawa attempts to lead his remaining aircraft in a coordinated attack on the climbing P38s, but the laws of physics work against him. His zero service ceiling is 33,000 ft in perfect conditions. The P38s are operating comfortably at 35,000 ft using their turbo superchargers to maintain full power at altitude where zero engines gasp for oxygen.

Our eye can’t catch up. Dash crackles through his radio as his pilots struggle with the realization that they’re fighting aircraft that exist in a different performance envelope entirely. Sergeant Yamamoto flying zero number A I167 attempts a climbing attack on a P38 that seems to be flying straight and level. Surely he thinks these twin engine monsters must be sluggish in a climb.

But as his zero struggles toward 28,000 ft, engine power fading in the thin air, the P38 simply accelerates upward and away. Its twin engines maintaining full power through altitude that leaves the Zero helpless. The psychological impact is immediate and devastating. These are pilots who have never been outclimbed, never been outrun, never been so completely outclassed that their skill and experience become irrelevant.

Captain Lynch coordinates the second attack with cold precision, having watched the Japanese formation’s confused response to the first pass. Fox two flight, take the trailing elements. Fox 3, come in from the north. Don’t get drawn into a turning fight. Hit and run. The P38s dive again, and this time the Japanese formation begins to disintegrate.

Three more zeros fall to the concentrated nose armament. Their pilots never having faced weapons that fire with such accuracy. Wing-mounted guns require convergence calculations, careful positioning, precise range estimation. But the P38’s nose guns fire straight ahead. If the aircraft is pointed at the target, the weapons hit the target.

Lieutenant Nishazawa realizes with growing horror that his tactical experience is useless against these aircraft. Everything he’s learned about aerial combat assumes opponents with similar performance characteristics. But these twin boomed fighters aren’t just better. They’re operating under completely different rules.

He attempts one final coordinated attack, gathering his three remaining zeros for a head-on pass against the reforming P38s. It’s a desperate gambit, but perhaps superior Japanese marksmanship can overcome the performance deficit. The head-on pass lasts 3 seconds. Rex Lamb, flying his first combat mission, finds himself nose tonose with a charging zero at a closing speed of over 700 mph.

His training takes over. Center the target in the gunsite. Squeeze the trigger smoothly. Hold the trigger down. The concentrated firepower of five weapons firing straight ahead meets the distributed firepower of two wing-mounted guns firing at converging angles. The Zero’s pilot, veteran though he is, is trying to hit a target while pulling significant G forces in a high-speed turn.

Lamb is flying straight ahead, his aircraft stable, his weapons fixed to fire along his line of flight. Physics determines the outcome. The Zero explodes in a shower of debris that hammers against Lamb’s P38 canopy like metallic hail. Nishiawa’s remaining two aircraft flee south toward Rabal. Their pilots confidence shattered along with their tactical doctrine.

Behind them, 18 P38 Lightnings reform in perfect formation, having destroyed six zeros without loss. But the true victory isn’t measured in aircraft destroyed. It’s measured in the psychological transformation that has just occurred. Japanese pilots, for the first time since Pearl Harbor, have encountered American fighters that are simply superior.

Not better flown, not better positioned, just better. In the cockpit of his undamaged Zero, racing south over Bugganville at maximum speed, Nishazawa’s mind reels with the implications. The twin boomed fighters, P38s, intelligence would later confirm, represent a fundamental shift in Pacific Air combat. Japanese pilots can no longer assume performance superiority.

They can no longer dictate engagement terms. They can no longer fight the kind of war they’ve been trained to fight. As Henderson Field fades behind him, Nishiawa keys his radio. Honuo Atarashi, America Gene Notoki. To Hayaku, Totomoi report to headquarters. New American fighter. Very fast, very strong.

It’s the understatement of the Pacific War. Behind him, the P38 Lightnings are landing at Henderson Field. Their twin engines winding down after combat that has fundamentally altered the balance of power in the Solomon Islands. The pilots climb out of their cockpits with expressions of stunned satisfaction. Having just participated in one of the most one-sided aerial victories in military history, the age of the P38 Lightning has begun.

The age of Japanese air superiority is over. The intelligence report reaches Rabal that evening, but its implications take weeks to fully sink in throughout the Japanese Navy’s airarm. Lieutenant Commander Nishawa’s account of the December 27th engagement reads like science fiction to pilots who have grown accustomed to Japanese air superiority.

American twin engine fighters speed approximately 650 kmh service ceiling above 10,000 m concentrated forward firing armament. Pilots avoided turning engagements entirely using speed and altitude advantages to attack and withdraw at will. Rear Admiral Yamamoto reads the report three times before summoning his staff. The implications are staggering.

Not just tactically, but strategically. If the Americans have developed fighters that can neutralize the Zero’s advantages, the entire defensive perimeter strategy collapses. Within days, similar reports flood in from across the Solomon Islands. P38 squadrons are appearing everywhere. The 339th Fighter Squadron, the 18th Fighter Group, elite units equipped with aircraft that render Japanese fighter tactics obsolete overnight.

Japanese ace Saburro Sakai, recuperating from injuries sustained in earlier combat, receives detailed accounts from surviving pilots. His later memoir captures the psychological shock. The P38 was the most formidable opponent we faced. It could outrun us, outclimb us, and engage us on its own terms. For the first time, Japanese pilots found themselves in aircraft that were simply inferior.

But the impact extends far beyond individual pilot psychology. The P38’s arrival forces a complete revision of Japanese defensive strategy. Aircraft that once dominated Allied bombers with impunity now face fighter escorts they cannot catch. Airfields that once seemed secure now face attacks by fighters with unprecedented range. The entire tempo of Pacific air warfare shifts in America’s favor.

Captain Tom Lynch’s 347th Fighter Group becomes the template for P38 operations throughout the Pacific. By February 1943, lightning squadrons are operating from bases across New Guinea, the Solomons, and the Northern Territory of Australia. Each deployment follows the same pattern. Initial Japanese confusion followed by desperate tactical adaptations followed by grudging acceptance of American air superiority.

The human cost for Japanese pilots is devastating. Men like Nishawa, veteran aviators with hundreds of combat hours, find their expertise rendered obsolete overnight. Worse, the replacement pilots arriving from Japan lack the experience to adapt to the new reality. P38s begin achieving kill ratios that seem impossible.

10:1 15:1 ratios that reflect not just superior aircraft but the psychological demoralization of an enemy that has lost technological supremacy. Rex Lamb survives the war with 12 confirmed victories, all scored in his P38. Years later, he reflects on that first combat engagement. We knew the Lightning was fast, but we didn’t understand what that speed meant tactically until we used it against the Zero.

It wasn’t just about performance specifications. It was about rewriting the rules of aerial combat entirely. The strategic implications ripple throughout 1943 and beyond. Japanese offensive operations in the Solomons become unsustainable when every bomber formation faces P38 escorts that can match the escort speed and outperform defending fighters.

The famous April 18th, 1943 interception of Admiral Yamamoto’s aircraft becomes possible only because P38s possess the range and performance necessary for such an audacious mission. By war’s end, P38 Lightnings have compiled one of the most impressive combat records in aviation history. Over 10,000 aircraft produced.

More than 1,800 Japanese aircraft destroyed in aerial combat. Two of America’s top five fighter aces, Richard Bong and Thomas Maguire, achieved their victories exclusively in P38s. But perhaps the most significant impact is psychological. The twin boommed fighter that Japanese pilots initially dismissed as ungainainely becomes the symbol of American technological supremacy.

The forktailed devil nickname originally applied by German pilots spreads throughout Japanese aviation with a mixture of fear and grudging respect. The December 27th, 1942 engagement over Guadal Canal lasts less than 20 minutes, but its consequences reshape the Pacific war. In those few minutes, Japanese pilots discover that American industrial might has finally produced fighters superior to their beloved Zero.

The shock of that discovery reverberates through Japanese military psychology for the remainder of the war. Today, aviation historians recognize the P38’s first combat appearance as one of the pivotal moments in Pacific Air Warfare. The moment when technological innovation overcame tactical experience. When American engineering answered Japanese pilot skill, when the twin boommed lightning announced that the age of zero supremacy was over.

The Japanese pilots were right to be shocked. They were witnessing the future of aerial combat. And it belonged to America.

News

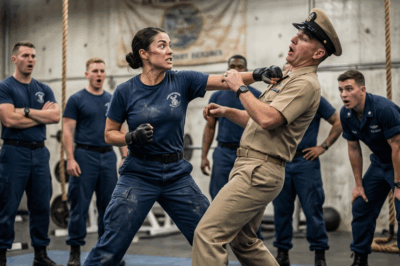

Lieutenant Struck Her In The Jaw Then Learned Too Late What A Navy SEAL Can Really Do

Lieutenant Struck Her In The Jaw Then Learned Too Late What A Navy SEAL Can Really Do The gym…

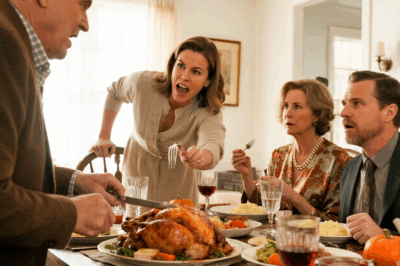

At Thanksgiving Dinner, I Asked My Parents If The Hospital Had Sent The Surgery Appointment. “They Did, But We Used Your Surgery Money For Your Brother’s Birthday. He Only Has One Birthday A Year.”

At Thanksgiving Dinner, I Asked My Parents If The Hospital Had Sent The Surgery Appointment. “They Did, But We Used…

He Looked Me Dead In The Eyes And Said, “We Need A DNA Test.” Not In Private. Not Gently. But Right There—at The Dinner Table, In Front Of Our Teenage Daughter And His Entire Family.

He Looked Me Dead In The Eyes And Said, “We Need A DNA Test.” Not In Private. Not Gently. But…

My Parents Took Me to Court for Buying a House With My Saving in 6 Years – They Said “That House Belongs to Your Sister”…

My Parents Took Me to Court for Buying a House With My Saving in 6 Years – They Said “That…

My Niece Whispered, “People Like You Have No Place At Our Table,” And The Whole Family Laughed, But I…

My Niece Whispered, “People Like You Have No Place At Our Table,” And The Whole Family Laughed, But I… …

They Mocked Me at the Military Gate. Seconds Later, the General Saluted Me.

They Mocked Me at the Military Gate. Seconds Later, the General Saluted Me. My name is Rachel Monroe. On…

End of content

No more pages to load