Japanese Admirals Never Knew Iowa’s 16 Inch Guns Could Hit From 23 Miles- Until They Had To Learn The Lesson Paid With 4 Of Their Ships

February 17th, 1944. The lagoon at Truk burned under a tropical sky thickened by columns of black smoke that blotted out the sun. Beneath that rising wall of fire and ash, the Pacific’s bluest waters had turned a dark, oily sheen, reflecting the twisted wreckage of what only hours before had been the pride of Japan’s Combined Fleet. From the bridge of the battleship USS Iowa, moving at 32 knots through the chaos, Captain John McCrae stared down at his plotting table, the rhythmic hum of machinery and shouted coordinates filling the air around him. The numbers he read told a story more staggering than anything his crew had yet seen in the war.

Carrier strikes had already smashed through Japan’s defenses. Dozens of merchant ships burned in the lagoon. Hundreds of aircraft — more than 250 by some counts — had been destroyed in the air and on the ground. The “Gibraltar of the Pacific,” as Japanese officers once proudly called Truk, had become a floating scrapyard. But as McCrae read the latest intelligence from Task Force 58, something new emerged from the static-filled radio chatter — a small flotilla of Japanese warships, survivors of the carrier raids, fleeing north through the coral passes.

On his flagship USS New Jersey, Admiral Raymond Spruance, commanding the U.S. Fifth Fleet, listened as his staff officers debated what to do. The fleeing Japanese ships — the light cruiser Katori, destroyers Mikatsuki and Nowaki, and the auxiliary cruiser Akagi Maru — were damaged but still moving fast. Carrier aircraft had hit them, but the sea was wide, and there was no guarantee they would sink before reaching open ocean. Most commanders in Spruance’s position would have let them go, leaving the bombers to finish the work. But Spruance wasn’t most commanders.

He wanted a surface action.

Even among his staff, the order drew glances. The era of great gun duels was supposed to be over. Since Pearl Harbor, air power had ruled the Pacific. Yet Spruance, calm and analytical as ever, saw an opportunity. These ships were battered, running for their lives, their escape routes limited by the reefs and the geometry of the lagoon. If the Iowa and her sister ship New Jersey could intercept, it would be more than a mop-up operation — it would be a demonstration. A message, not just to Japan, but to the world, that the new generation of American battleships could strike from distances once thought impossible.

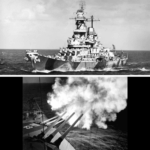

On Iowa’s bridge, McCrae relayed the order. The ship’s great turbines roared to life, and 45,000 tons of steel surged forward, slicing through the Pacific like a blade. Below decks, the gun crews prepared the ship’s main battery — nine 16-inch/50-caliber Mark 7 naval rifles, each capable of firing a 2,700-pound shell more than twenty miles. The sound of the hydraulic turrets turning echoed through the hull, a slow, mechanical groan that every sailor aboard recognized.

What would follow that day would set a record that still stands: the longest-range gunnery engagement between battleships and surface vessels in naval history. Yet beyond the statistics, beyond the record books, it would reveal something the Imperial Japanese Navy had never truly understood — that American battleships were not merely bigger or tougher. They were more precise, more intelligent, and more deadly than anything the Japanese high command had ever imagined.

To grasp why the events at Truk stunned Japan’s naval leadership so completely, you have to understand how both nations thought about naval warfare. For decades, since their victory over the Russians at the Battle of Tsushima in 1905, Japan’s entire naval doctrine had been built on a single concept: Kantai Kessen — the decisive battle. The theory was that one great clash of fleets, fought by battleships manned by superior sailors and driven by unbreakable spirit, would decide the outcome of any war.

The Japanese Navy believed that victory came not from machines but from men — their discipline, their courage, their ability to fight at close range. To them, range was not just a technical factor but a moral one. The decisive battle would be fought where the human eye could still see the enemy — at ten or fifteen miles, within visual distance, where optical rangefinders could guide the guns and commanders could feel the rhythm of combat.

Their entire fleet was built for this vision. Their gunnery officers trained to use massive 15-foot optical rangefinders mounted high on superstructures, scanning the horizon for enemy silhouettes. Their crews drilled relentlessly in coordinated fire at medium ranges, where the color of the sea and sky could still be judged by the naked eye. They believed that closing the distance was a test of honor and skill.

And in fairness, it wasn’t ignorance. Japanese naval intelligence was meticulous. They knew the specifications of American ships — the Iowa’s tonnage, her armor thickness, her shell weight, even her top speed. They knew the theoretical range of her 16-inch guns. But “theoretical” was the key word. On paper, yes, the American guns could reach beyond twenty miles. In practice, Japanese officers dismissed those figures as academic. No gun, they believed, could be fired with accuracy at targets that couldn’t even be seen.

That was their mistake.

What they didn’t realize — what they couldn’t truly grasp until that February morning — was that American battleships no longer relied on the human eye at all.

In the control tower of the Iowa, humming softly behind steel bulkheads, was the heart of a revolution: the Mark 8 radar-directed fire control system. Unlike the Japanese, who depended on optical rangefinders, the U.S. Navy had developed radar systems capable of seeing far beyond the horizon, in fog, smoke, or total darkness. The Mark 8 radar, installed on the Iowa-class ships, could track a moving target more than twenty miles away with astonishing precision.

The radar data fed directly into a device that looked more like a vault than a weapon — an analog fire control computer known as the Ford Mk.1A Rangekeeper. Inside, gears, cams, and rotating drums worked in harmony, performing thousands of calculations every second. The Rangekeeper didn’t just account for the target’s position; it considered its speed, heading, and even the movement of the firing ship itself. It corrected for wind direction, air density, powder temperature, and the Earth’s rotation.

When the Iowa’s gunnery officer received the data, he wasn’t guessing where to shoot. He knew. The ship’s gunners no longer needed to see their enemy to hit them. They needed only a radar echo — a ghost on a screen — and the confidence that mathematics, not eyesight, would deliver steel to its mark.

Meanwhile, Japanese ships still relied on the human eye. Their gunnery officers peered through rangefinders and telescopes, instruments that were elegant and sophisticated for their time but powerless against distance, smoke, or darkness. When visibility dropped, so did accuracy.

That morning, the American fleet’s carrier strikes had already done catastrophic damage. Task Force 58 under Admiral Marc Mitscher launched wave after wave of aircraft from carriers like Enterprise and Yorktown. Dive bombers tore through the sky, their sirens screaming as they plunged onto anchored ships. Torpedo planes struck from sea level, leaving trails of white foam as they released their payloads. Fighters strafed fuel depots, hangars, and airstrips. The lagoon that had once glittered with Japanese pride was now a cauldron of fire and oil.

For nearly two years, Truk had been the beating heart of Japan’s Pacific defense — the forward base for its Combined Fleet, where the massive battleships Yamato and Musashi had anchored, where aircraft carriers had replenished and refueled, and where submarines prowled out to cut American supply lines. Its natural lagoon, protected by coral reefs and surrounded by volcanic islands, had been considered impregnable. American submarines could stalk its exits, but no one had dared to strike directly — until now.

By midmorning, the unthinkable had happened. The lagoon was littered with burning ships, and columns of smoke reached 20,000 feet into the sky. Japanese sailors abandoned their vessels, leaping into the oil-slicked waters as explosions rolled across the harbor.

But outside the lagoon, through the narrow northern channels, a handful of survivors were still running — and on the Iowa’s bridge, Captain McCrae and his men were closing fast.

Every man aboard could feel it — the moment when history tilted from old doctrine to new reality. The Japanese believed their ships were too far away to be hit. They were wrong. And in the next hours, as the Iowa’s radar-guided guns prepared to speak across twenty-three miles of open ocean, they would learn a lesson written not in theory or philosophy, but in fire and steel.

The lesson would cost them four ships.

And for the first time in the Pacific War, the Imperial Japanese Navy would discover what it meant to fight an enemy who could see in the dark — and strike from beyond the horizon.

Continue below

February 17th, 1944. The lagoon at truck burns under a tropical sky turned black with smoke inside the bridge of USS Iowa moving at 32 knots through Azure waters that had been until hours ago Japan’s untouchable fortress. Captain John McCrae stands before the plotting table. The numbers coming through are staggering. Carriers have already sunk dozens of merchant ships.

250 Japanese aircraft destroyed on the ground or in the air. But now something different. A group of warships fleeing north through the passes. Admiral Raymond Spruent, commander of the fifth fleet, has made a decision that surprises even his own staff. He wants a surface action. The light cruiser Couturi, destroyers Mikaz and Noaki, the auxiliary cruiser Akagi Maru.

Already battered by carrier aircraft, they’re running for their lives. And Iowa along with her sister New Jersey is being unleashed to finish them. What happens in the next 2 hours will set attempts of the effort record that stands to this day. The longest range engagement between battleships and surface vessels in naval history.

But more than that, it will demonstrate something the Japanese high command had never fully grasped. American battleships didn’t just have bigger guns or thicker armor. They had something far more dangerous. The ability to hit what they aimed at from distances previously thought impossible.

If you’re enjoying this deep dive into the story, hit the subscribe button and let us know in the comments from where in the world you are watching from today. To understand why the engagement at Truck represented such a shock to Japanese naval thinking, you have to go back to how both navies understood battleship combat.

For decades, perhaps since the battle of Tsushima in 1905, the Imperial Japanese Navy had built its entire strategic doctrine around a concept called Canai Kessan. The decisive battle won enormous fleet action where Japanese battleships manned by superior trained crews imbued with fighting spirit would close to medium range and destroy the American battle line through courage, skill, and the weight of their shells.

Range wasn’t just a technical specification. It was wrapped up in an entire philosophy of warfare. Japanese naval theorists believed that battles would be decided at ranges of perhaps 10 to 15 m. Close enough for optical rangefinders to be effective. Close enough for the human element, crew training, and fighting spirit to matter decisively.

The idea that shells could be accurately placed on target from beyond the horizon, from distances where the enemy ships couldn’t even be seen with the naked eye, seemed more theoretical than practical. This wasn’t ignorance. Japanese naval intelligence was extensive and professional. They knew in general terms what American battleships could do on paper. They knew the specifications, range, shell weight, armor thickness.

What they didn’t fully appreciate, what they couldn’t quite believe until they saw it with their own eyes was the fire control. American radar directed fire control systems, particularly the Mark 8 fire control radar mounted on the Iowa class battleships, represented a revolution in naval gunnery.

While Japanese warships still relied primarily on optical rangefinders, impressive devices in their own right, but fundamentally limited by visibility, weather, and distance. American battleships could calculate firing solutions in conditions where the target was barely visible or not visible at all. The system worked like this. Radar detected the target and provided continuous range and bearing data.

This information fed directly into an analog computer, a mechanical marvel called a rangekeeper. The rangeeper factored in not just the target’s position, but its speed and course. The speed and course of the firing ship. wind direction and velocity, air temperature and density, even the rotation of the Earth.

It calculated where the target would be by the time a shell traveling for perhaps a minute and a half through a parabolic arc reaching heights of over 7 mi finally arrived. This wasn’t guesswork. It wasn’t a salvo fired in hope. It was mathematics made lethal. And the Japanese, for all their intelligence gathering, had never quite internalized what this meant in practice.

They had built the Yamato and Mousashi, the largest battleships ever constructed, mounting 18-in guns that could theoretically outrange anything afloat. But theoretical range and effective range are very different things. Without comparable fire control, those mighty guns were limited to distances where optical sighting might work.

Meanwhile, American battleships with smaller but better controlled 16-in guns could engage effectively at ranges the Japanese had never seriously practiced. The morning of February 17th began with carrier strikes. Task Force 58 under Admiral Mark Mitcher unleashed wave after wave of aircraft against truck. The base had been for 2 years considered Japan’s Gibralar of the Pacific, a vast natural harbor protected by reefs and defended by hundreds of aircraft.

American submarines had lurked outside, sinking ships that ventured out, but no one had dared a direct assault. Until now, by mid morning, the lagoon was a graveyard. Merchant ships burned at anchor. Destroyers and cruisers caught unprepared had been bombed and torpedoed. The air rire of burning oil and cordite. Japanese pilots scrambling desperately to defend their base were being shot down by American fighters in numbers that preaged what would later be called the great Mariana’s turkey shoot.

Light cruiser Couturi, serving as a training vessel, had been morowed inside the lagoon. Her captain, Takao Saii, recognized immediately that staying meant certain death. At 0430 hours, before the American strike even began, Couturi had slipped out through the North Pass, accompanied by the auxiliary cruiser Akagi Maru, destroyers Mikaz and Noaki, and the small mind sweeping twer Shaunan Maru number 15.

They were running, hoping to reach Saipan, hoping the Americans would be too focused on targets inside the lagoon to notice a few ships making for open water. They almost made it, but American reconnaissance planes spotted them. Reports reached Admiral Spruent, commanding from the heavy cruiser Indianapolis. His carriers had wrought devastation inside the lagoon.

Aircraft were returning, some damaged, all low on fuel and ammunition. The standard procedure would be to let them go. Japanese ships fleeing truck could be hunted by submarines, by aircraft from other bases. Spruent, however, wanted something else. He wanted a surface action. He wanted his battleships and cruisers to close with the enemy and engage shipto- ship.

Some of his staff thought it reckless. Carriers could finish the job safely. Why risk capital ships? But Spruuans understood something. They didn’t. This war was proving again and again that carriers had replaced battleships as the decisive arm of naval warfare. But that didn’t mean battleships were useless. Not yet.

And he wanted to demonstrate both to his own navy and to the Japanese that American surface ships could still fight and win decisively. He formed task group 50.9, Battleships Iowa and New Jersey. heavy cruisers Minneapolis and New Orleans, four destroyers, light carrier cowpens providing air cover, and he put himself in tactical command. The chase was on.

The Japanese ships had perhaps a 2-hour head start. They were running at close to their maximum speed, around 26 knots for Couturi, 35 for the destroyers. But Iowa and New Jersey, the newest and fastest battleships in the American fleet, could make 33 knots. and they had radar. They didn’t need to see their quarry to track them.

Shortly after 1300 hours, American scout planes from Cowpens confirmed the Japanese position. Couttori and her escorts were 30 mi northwest of Tru heading roughly north, still running on Iowa’s bridge. Captain McCrae received updates from the fire control center. Range to target 32,000 yd, 18 statute miles.

The Japanese ships were still invisible to the naked eye, hull down beyond the horizon, but on the radar scope they were clear as day. Four distinct contacts moving steadily northeast. Admiral Willis Lee commanding the battleship division gave the order. Prepare for surface action. All ahead flank, increase speed to intercept. Below decks in the massive turrets, gun crews went to work.

Each turret designated one, two, and three contained three 16-in guns, nine guns total. Each barrel 66 ft long from breach to muzzle. Each shell, for the armor-piercing rounds, 2700 lb, nearly a ton and a half of steel and explosive, capable of punching through 2 ft of armor plate at 15 miles. The armor-piercing shells, designated Mark 8, were engineering marvels, a hardened steel cap at the tip to bite into armor, a ballistic cap to maintain velocity through the air.

Inside, a relatively small bursting charge. These weren’t designed to explode on contact like bombs. They were designed to penetrate deep into a ship’s vitals, then detonate, destroying magazines, engineering spaces, command centers, killing the ship from the inside.

For this engagement, though, the highcapacity shells Mark13 would be more suitable. 1,900 lb with a much larger bursting charge designed to create devastating fragmentation against lightly armored ships like destroyers and the thin- skinned couturi. These were the rounds of choice. In the plotting room, the rangekeeper hummed inputs from radar, inputs from the ship’s gyroscopic compass and speed indicators, the targets course and speed estimated and continuously updated. The system calculated the firing solution.

Barrel elevation needed [Laughter] [Music] lead angle to account for the targets. Even the wear on the gun barrels, which slightly reduced muzzle velocity after repeated firings, was factored in. At 14,500 yds, Iowa opened fire. 7 and A4 statute miles. Turret 2 spoke first.

Three guns, three shells, each weighing nearly a ton, launched at a muzzle velocity of 2600 ft pers. The recoil was enormous. The entire ship shuddered. The over pressure wave from the guns could injure unprotected personnel on deck. The blast deflectors, massive armored plates designed to protect the decks from the gun muzzle’s fury, glowed briefly from the heat. 45 seconds later, the first salvo arrived.

Couturi, already crippled by earlier air attacks, was attempting to maneuver. Her captain knew what was coming. Three shells arriving in a tight pattern. One fell short, one fell long. The third struck the water alongside, showering the ship with fragments and spray. A straddle, the next salvo would adjust.

Couturi’s crew fought back. Her 5-in guns designed for anti-aircraft work and defense against destroyers opened fire. She even got off a torpedo salvo, a desperate, defiant gesture. But the range was too great. Her optical rangefinders couldn’t get an accurate fix on ships hull down on the horizon.

The torpedoes ran wild, missing New Jersey by hundreds of yards. Iowa fired again and again. Each salvo was three shells. Each salvo adjusted based on where the previous one had fallen. The rangeeper updated continuously. The radar showed Couture’s course changes, slight alterations as she tried to evade, but there was no evading. At these ranges, the shells took almost a full minute to arrive, but the fire control system predicted where the ship would be, not where it was. The fourth salvo hit.

Multiple shells struck Couturi’s superructure and midship. The 1900 lb shells detonated with immense force. fragmentation sthed through anything not protected by heavy armor. And Couturi, a light cruiser, had very little heavy armor. Her bridge took a direct hit. Her engineering spaces were torn open. Fires erupted. The destroyer Mikazi, her consort, tried to stand by, tried to lay smoke, tried, gallantly and uselessly to draw fire from the dying cruiser.

She launched torpedoes of her own at Iowa and New Jersey. Lookouts on New Jersey spotted the torpedo wakes. The battleship altered course slightly. The torpedoes passed just ahead of the bow. One officer later remarked that it would have been embarrassing to be hit, but Micaz’s sacrifice bought nothing. American heavy cruisers Minneapolis and New Orleans had closed the range.

Their 8-in guns added their weight to the barrage, and carrier aircraft from cowpens circling overhead warned the surface ships of any submarine threat and confirmed hits. Couturi, her guns still firing even as she listed heavily, rolled over at 1343 hours, 11 minutes under fire. Captain Sai went down with his ship.

Large groups of survivors were seen in the water. Destroyer Burns attempted to rescue some of them, but the Japanese sailors trained to fight to the death refused rescue. Some attacked the American sailors. In the end, none were pulled from the water. None survived. Every man aboard Couturi, approximately 300 officers and crew, perished.

My Kaz, still fighting, became the next target. Outgunned 20 to1, she nonetheless closed to launch another torpedo attack. Minneapolis and New Orleans concentrated their fire. Shell after shell slammed into the 2,000 ton destroyer. She absorbed punishment that would have sunk three ships her size. Her crew fought until the magazine exploded and she broke in half.

All hands lost. Destroyer Noaki, seeing what had happened to her sister ships, made a run for it. She was faster than the battleships, capable of over 35 knots, and she had a head start. Iowa and New Jersey turned to pursue. Range opened to 34,000 yd, then 36,000, 19 mi, 20 statute miles, beyond the range where any battleship had ever scored a hit in combat. But the chase wasn’t about hitting.

It was about demonstrating capability. Iowa fired. New Jersey fired. Salvos arked out across the Pacific, shells climbing miles into the sky before plunging back down. At maximum elevation, 45°, the trajectory was almost like an artillery piece firing over a mountain. The shells fell around Noaki. One salvo straddled her, shells landing to port and starboard.

Splinters from near misses caused casualties and minor damage, but she was too fast, too far, and pulling away. At 35,700 yards, 20.3 statute miles, New Jersey fired what would be the final salvo of the engagement. It was a straddle. One shell splashed into the ocean to Noaki’s port side, another to starboard. The destroyer disappeared into rain squalls and opened the range. she would escape. But the point had been made.

23 mi had been listed as the theoretical maximum range of the Iowa class guns. 20.3 mi was the confirmed combat firing. The longest range gunnery engagement between surface vessels ever recorded. A record that stands today and will likely stand forever as no navy builds battleships anymore. The auxiliary cruiser Akagi Maru never even made it to the surface engagement.

carrier aircraft had caught her hours earlier. Three direct bomb hits and massive internal explosions. She was abandoned and sinking by the time Iowa opened fire on Couturi. The small mind sweeping twer Shaan Maru number 15 tried to run then tried to fight. Destroyer Burns dispatched her with 5-in gunfire. Like Couturi and Micaz there were no survivors.

Four ships, one escaped, three destroyed. In the span of 90 minutes, American surface vessels had demonstrated something that Japanese naval planners had never quite believed possible. Accurate, devastating fire from ranges that exceeded anything in their doctrine, their training, or their experience. But here’s where the story deepens. Because this wasn’t just about range.

It wasn’t just about hitting ships from 20 m away. Though that was remarkable enough, what made the engagement at Trrook truly significant, what made it a watershed moment in naval warfare was what it revealed about the fundamental assumptions underlying Japanese naval strategy and how catastrophically wrong those assumptions had been.

The Imperial Japanese Navy had not been complacent. They had not been ignorant. They had studied their potential enemy extensively. Japanese naval attaches in Washington before the war had filed detailed reports. They knew the specifications of American battleships. They knew about radar. They knew in technical terms what the systems could do. What they didn’t grasp.

What they couldn’t quite internalize until it was demonstrated in combat was the magnitude of the advantage these systems conferred. Consider the math. In a traditional gunnery engagement using optical rangefinders, a battleship might need to fire 20, 30, even 40 salvos to score hits on a maneuvering target at extreme range.

The first salvos were for ranging, finding the distance, then corrections for wind, for the target’s speed and course. The process was iterative, slow, and consumed enormous amounts of ammunition, and it only worked if you could see the target clearly. The Mark 8 fire control radar combined with the rangekeeper analog computer collapsed this process.

The first salvo might miss, but the second or third would straddle and the fourth would hit. Iowa had fired 46in shells at Couturi. In a 15-minute engagement, this was an extraordinarily efficient expenditure. Pre-war estimates suggested that scoring decisive hits on a cruiserized target at maximum range might require 200 shells or more. The Japanese had built their battleships differently.

The Yamato class, the pride of the fleet, mounted 18in guns, the largest naval rifles ever put to sea. Each shell weighed 3,200 lb, heavier than anything the Americans could fire, and the theoretical maximum range was slightly greater than even the Iowa class. On paper, the Yamato class ships outgunned anything afloat, but range without accuracy is just wasted ammunition.

And the fire control systems on Yamato and Mousashi, while sophisticated by the standards of optical rangefinding, were a generation behind American radar directed systems. The Japanese had radar, but it wasn’t integrated into fire control the way American systems were. Radar data had to be manually entered into the fire control calculations.

This took time, precious seconds, that at maximum range could mean the difference between a hit and a miss. More critically, Japanese naval doctrine had never emphasized long range gunnery. The decisive battle, the Kai Kessan they had trained for, was expected to occur at closer ranges, 10 mi, 12 mi, distances where optical rangefinders worked well and where crew training and fighting spirit could tip the balance.

Engaging at 20 mi wasn’t just difficult, it was considered wasteful. Better to close the range, they believed, and fight where Japanese superiority in night fighting and torpedo tactics could be brought to bear. Troo shattered this illusion, but by February 1944, illusions were all Japan had left.

The strategic situation in the Pacific had already turned decisively against them. Guadal Canal had been evacuated a year earlier. The Central Pacific Drive was underway. The Marshall Islands had just fallen. Truck itself, once considered impregnable, had been bypassed and neutralized in a single devastating strike. And now, even in surface combat, the one arena where Japanese naval officers still believed their battleships might prevail through superior training and fighting spirit, American technological superiority had proven overwhelming. ships firing from beyond visual range, hitting targets

with a precision that seemed almost supernatural. It was to officers who had spent their careers training for close-range gunnery jewels, a bitter revelation. If you find this story engaging, please take a moment to subscribe and enable notifications. It helps us continue producing in-depth content like this. After the engagement, task group 50.9 returned to the fleet.

The butcher bill was tallied. American losses, zero. Not a single hit sustained. Not even a near miss that caused damage. Japanese losses, three warships sunk, one damaged and barely escaped. Over 800 Japanese sailors dead. The material victory was significant, but the psychological impact would prove even more important.

News of the engagement filtered back to Tokyo through surviving crew members of Noaki and through Japanese coast watchers who had observed parts of the action. The reports were confused, fragmentaryary, but one fact stood out. American battleships had engaged at ranges Japanese doctrine considered impractical, and they had scored hits quickly, efficiently, devastatingly.

For Japanese naval planners, this was deeply troubling. They had known theoretically that American technology was advanced. They had known their industrial capacity dwarfed Japan’s. But the assumption had always been that in actual combat, factors would even out. Japanese crews were more experienced. Japanese fighting spirit was superior.

Japanese tactics developed through years of rigorous training would compensate for any material disadvantage. truck demonstrated that this was wishful thinking. Superior fighting spirit couldn’t compensate for being hit by shells fired from beyond visual range.

Excellent crew training didn’t matter if the enemy could calculate firing solutions faster and more accurately than any human crew could manage with optical sights alone, and superior tactics were meaningless if the enemy could engage at ranges where those tactics couldn’t even be employed. The engagement also highlighted another even more fundamental problem. By February 1944, Japan had already lost the naval war, not in the sense of a single decisive battle, but through attrition, through the steady, grinding destruction of their merchant fleet by American submarines, through the loss of carriers at Midway, the Solomon Islands, and the Philippine Sea. Through the loss of

trained pilots, which couldn’t be replaced at anything approaching the rate the Americans were producing new aviators, the battle of truck, if it can even be called a battle, was a footnote. Three Japanese ships sunk. Strategically insignificant, but symbolically it was devastating because it proved that even in surface combat, even in the arena where battleships were supposed to reign supreme, American technology had rendered Japanese numerical and qualitative advantages meaningless.

Let’s talk about those Iowa class battleships because understanding what they were and more importantly what they represented is crucial to understanding why troo mattered. USS Iowa BB61 was commissioned in February 1943. She was the lead ship of her class. Six ships were planned. Four were completed.

Iowa, New Jersey, Missouri, and Wisconsin. Two were cancelled before construction finished. They were the last battleships the United States Navy would ever build. They were fast, 33 knots, faster than most cruisers. This speed came at a cost. To achieve it, the hull had to be long and relatively narrow, 887 ft long, but only 108 ft at the beam.

This gave them a sleek profile, but it also meant they were less heavily armored than the preceding South Dakota class. The armor was carefully designed, concentrated on vital areas. The main belt was 12 and 1/4 in thick. The turret faces were 17 in, enough to protect against 16in shells at most combat ranges, but not invulnerable. The main battery was 96in 50 caliber Mark 7 guns.

The designation 50 caliber means the barrel was 50 times the diameter of the bore. 50 * 16 in equals 800 in or 66.7 ft. Nearly 70 ft of rifled steel barrel. Each gun weighed 267,900 lb with the breach mechanism over 120 tons. They fired two types of shells. the armor-piercing Mark 8 at 2700 lb and the high-capacity Mark13 at,900, a full broadside, all nine guns firing simultaneously through nearly 12 tons of steel and explosive.

The rate of fire was approximately two rounds per gun per minute, though in practice sustained fire was slightly slower due to the time needed to reload the massive shells and powder charges. The powder charges themselves were remarkable. Six silk bags per gun, each containing 110 lbs of smokeless powder. The bags were handled with extreme care.

Any spark, any static electricity, could cause a catastrophic explosion. The powder was sensitive enough that temperature variations had to be accounted for in the firing calculations. Warmer powder burned slightly faster, altering muzzle velocity and thus range and trajectory. The secondary battery was 25 in 38 caliber dualpurpose guns.

These could engage both surface targets and aircraft. At nearly 9 statute mi range, they could hit destroyers or shore targets, and with proximity fused shells, they could create air bursts deadly to incoming aircraft. Rounding out the armament were dozens of 40mm bofers and 20mm Ericon anti-aircraft guns.

But the real weapon, the system that made everything else possible, was the fire control. Two Mark 38 directors controlled the main battery. Each director contained a Mark 8 fire control radar and a complex optical rangefinder as backup. The directors fed data into the Mark 1A fire control computer, a mechanical analog marvel weighing several tons and containing thousands of precisely machined gears, cams, and linkages.

The computer solved differential equations in real time. It calculated the ballistic trajectory of shells in three dimensions. It accounted for the curvature of the earth, the corololis effect caused by the planet’s rotation, air density variations at different altitudes, the drift of the ship caused by wind and current, and critically it predicted where the target would be by the time the shells arrived. This was revolutionary.

Previous fire control systems required manual calculation and constant adjustment. The Mark 1A did it automatically, continuously, updating the firing solution several times per second. The result was that Iowa could fire accurately at targets she couldn’t even see with optical rangefinders in fog at night beyond the horizon.

As long as radar could detect the target, the guns could engage it. The engagement at Trrook demonstrated this capability in combat for the first time. And it terrified the Japanese because they realized that their most powerful battleships, Yamato and Mousashi, despite their heavier armor and bigger guns, couldn’t match this. The biggest guns in the world were useless if they couldn’t hit what they aimed at.

And the thickest armor was meaningless if the enemy could fire accurately from ranges where return fire was ineffective. But here’s the deepest irony. the one that makes this story not just a tale of technological superiority but a parable about the nature of warfare itself. By the time Iowa demonstrated the supremacy of radar directed gunnery, battleships were already obsolete.

The engagement at Trrook was the only time Iowa or New Jersey ever fired their main guns at enemy surface vessels in anger during World War II. The only time aircraft carriers had already proven themselves the decisive weapon. At the Coral Sea, at Midway, at the Philippine Sea, at Later Gulf, the largest naval battle in history, battleships fired their guns. But the battle was decided by aircraft.

By 1944, the battleship’s role had been reduced to shore bombardment, anti-aircraft escort for carriers, and occasionally, as a truck, hunting down damaged or inferior enemy vessels. The Iowa class ships were in a sense the ultimate expression of a dying weapon system. Faster, more accurate, more sophisticated than any battleships that had come before, but still battleships still tied to a mode of warfare that aircraft had rendered obsolete.

They were magnificent anacronisms built to fight a war that no longer existed. This is what the Japanese admirals never fully understood. It wasn’t just that Iowa’s guns could hit from 23 mi. It was that hitting from 23 mi didn’t matter anymore. Not when carrier aircraft could strike from 200 m. Not when a single carrier could project more destructive power than an entire battleship squadron.

The question wasn’t whether Japanese battleships could match American battleships in a gunnery duel. The question was whether battleships mattered at all. And the answer by mid 1944 was increasingly no. Yamato and Mousashi would both be sunk by aircraft. Yamato in April 1945 on a one-way suicide mission to Okinawa. Mousashi at Lee Gulf in October 1944.

Neither ship ever engaged an enemy battleship. Their massive 18-in guns, the most powerful naval artillery ever mounted on a warship, fired at aircraft, at destroyers, but never at the American battleships they were designed to destroy. The Iowa class ships had longer careers. They were reactivated for Korea where they provided shore bombardment.

New Jersey saw service in Vietnam. All four were brought back into service in the 1980s, modernized with cruise missiles and anti-ship missiles. They fired their guns in combat for the last time during Operation Desert Storm in 1991 when Missouri and Wisconsin bombarded Iraqi positions in Kuwait. But even then, they were relics, impressive relics, floating museums of a bygone era.

The cruise missiles they carried had longer range and greater accuracy than their 16-in guns. The aircraft flying from carriers hundreds of miles away delivered more ordinance more precisely. The battleships were kept in service partly for shore bombardment, partly for intimidation value, and partly because no one quite knew what else to do with them. Now all four are museum ships.

Iowa in Los Angeles, New Jersey in Camden, Missouri in Pearl Harbor, appropriately mored near where the war began. Wisconsin in Norfolk. Visitors can walk their decks, stand in the turrets, marvel at the machinery. But the era they represent is gone. The age of the battleship ended not with a dramatic last stand, but with a quiet acknowledgement that other weapons were simply more effective.

The engagement at Trrook stands as a peculiar moment in this transition, a demonstration of technological superiority in a weapon system that was already being superseded. Japanese admirals were shocked that Iowa could hit from 23 mi, but they should have been more concerned about the carriers that had destroyed 250 aircraft and dozens of ships earlier that same day.

Still, for the men who served on Iowa, for the crew who loaded the shells and fired the guns and maintained the machinery, Troo was proof that their ship, their weapons mattered, that they weren’t just along for the ride while aircraft did the real fighting. For 90 minutes on February 17th, 1944, battleships were relevant again. guns mattered and the skills and systems they had trained on, the massive technological apparatus of radar and computers and precision engineering had proven themselves in combat.

Captain McCree wrote in his action report that the engagement demonstrated the effectiveness of radar directed fire control at extended ranges. He noted that Couturi had been quickly destroyed despite her attempts at evasion and that the Japanese return fire had been ineffective. He recommended that future surface engagements employ maximum range radar directed fire as standard doctrine.

His recommendations were noted and then quietly filed away. Because by the time the report reached Washington, planners were already focusing on the invasion of the Maranas, on carrier operations, on submarine warfare, on everything except battleship versus battleship combat, which seemed increasingly unlikely to ever occur again. for Japanese.

The lessons of TR were learned too late to matter. Reports reached the naval general staff in Tokyo. Engineers studied what little information could be gleaned from survivors. They understood finally just how far behind they had fallen in fire control technology. Plans were drawn up to retrofit Japanese battleships with improved systems.

But by early 1944, Japan lacked the industrial capacity, the resources, and most critically the time to implement such upgrades. The war was already lost. Truck had demonstrated it, not because of the four ships sunk, but because of what those sinkings represented. American technology, American industry, American systems were superior across every dimension of naval warfare, fire control, radar, damage control, logistics, industrial production, pilot training, codereaking.

The Japanese could still fight, their sailors were still brave, their ships still dangerous. But bravery and danger couldn’t compensate for estimatic overwhelming superiority in every measurable category. One Japanese naval officer interviewed after the war described the feeling when news of Troo reached fleet headquarters.

We knew then, he said, that we were fighting a war we had already lost. Not just the battle, but the war. They could do things we couldn’t do, build things we couldn’t build, and they could do it faster and better. We had hoped that fighting spirit would compensate. After TR, we knew it wouldn’t.

This realization spread through the combined fleet, not all at once, not uniformly. Some officers still believed in the possibility of a decisive battle. Some still thought that one great victory, one crushing blow could force the Americans to negotiate. But increasingly the prevailing mood was fatalistic.

The question wasn’t whether Japan would lose, it was when and at what cost. The final tally from Operation Hailstone makes for grim reading. From the Japanese perspective, over 200 aircraft destroyed, three light cruisers sunk, six destroyers sunk, numerous smaller warships and auxiliary vessels destroyed, 32 merchant ships and transports totaling over 200,000 tons sent to the bottom.

All accomplished in two days with American losses of 21 aircraft and approximately 100 casualties. Truck, once considered the Gibraltar of the Pacific, was rendered useless. The garrison remained cut off, starving until the end of the war. But as a functioning base, it ceased to exist on February 18th, 1944. And the surface engagement, the 90-minute gun battle that sank Couturi and Micazi and demonstrated the Iowa class battleship’s capabilities was almost forgotten in the larger destruction.

Almost, but not quite. Because for the men who served on Iowa and New Jersey, for the officers and crews who had loaded those shells and fired those guns and watched through binoculars as enemy ships burned and sank, it mattered. It proved that their ship, their weapons, their training had value.

That even in a war dominated by aircraft carriers and submarines, there was still a place for the big guns. They were wrong. Of course, history would prove them wrong. But in that moment, in the waters northwest of Trrook, with smoke rising from the lagoon behind them, and the record for longest range naval gunfire engagement set, and likely never to be broken, they had every right to believe they mattered. Thank you for watching.

For more detailed historical breakdowns, check out the other videos on your screen now.

News

CH2 What Eisenhower Told Staff When Patton Turned His Army 90 Degrees in 48 Hours Shocked The Entire Meeting

What Eisenhower Told Staff When Patton Turned His Army 90 Degrees in 48 Hours Shocked The Entire Meeting In…

CH2 How One Mechanic’s “Illegal” Engine Trick Made Mosquito Bombers Outrun Every German Fighter

How One Mechanic’s “Illegal” Engine Trick Made Mosquito Bombers Outrun Every German Fighter The De Havilland Mosquito shouldn’t have worked….

CH2 When a 72-Hour Retreat Turned Into a 300-Mile Counterattack That Germany Never Believed Possible

When a 72-Hour Retreat Turned Into a 300-Mile Counterattack That Germany Never Believed Possible At dawn on February 20th, 1943,…

CH2 The Army Tried to Kick Him Out 8 Times — Until He Defeated 700 German Troops with Just 35 Men

The Army Tried to Kick Him Out 8 Times — Until He Defeated 700 German Troops with Just 35 Men…

CH2 How One Farmhand’s “STUPID” Rope Trick Destroyed 35 Zeros in Just 3 Weeks

How One Farmhand’s “STUPID” Rope Trick Destroyed 35 Zeros in Just 3 Weeks May 7th, 1943. Dawn light seeped…

CH2 They Banned His “Fence Post” Carbine — Until He Dropped 9 Japanese Snipers in 48 Hour

They Banned His “Fence Post” Carbine — Until He Dropped 9 Japanese Snipers in 48 Hour At 2:17 a.m….

End of content

No more pages to load