Japan Rigged Their Own War Games To Win – But Then Lost Exactly Like The Dice Predicted

At precisely 9:30 a.m. on May 1st, 1942, the air inside the battleship Yamato’s converted mess hall felt thick with cigarette smoke and expectation. The most powerful men in the Imperial Japanese Navy had gathered to play what was supposed to be a game—but everyone in that room knew it was much more than that. Rear Admiral Matome Ugaki, a meticulous and soft-spoken man whose reputation for loyalty to Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto bordered on devotion, stood near the great table that dominated the room. Spread across it was a detailed map of the Pacific Ocean, its blue expanse marked by carefully drawn grid lines, tiny model ships, and pins of red and white.

Around the table stood Japan’s naval elite—twenty senior admirals in pressed uniforms, each trailed by aides burdened with folders of operational charts and tactical diagrams. Every man present knew the stakes. Japan’s empire had grown faster than anyone thought possible. The war game they were about to begin would decide whether that expansion would continue—or whether Japan’s luck had already reached its peak.

The exercise was meant to simulate the upcoming operation against a small speck of land called Midway Island, a coral atoll in the middle of the Pacific, some 1,400 miles northwest of Hawaii. Yamamoto’s grand strategy was deceptively simple: lure the remaining American aircraft carriers into battle by threatening Midway, destroy them in one decisive blow, and force the United States to the negotiating table. The plan was to be Japan’s masterpiece, its final stroke of brilliance that would secure domination of the Pacific. But the war game designed to test this strategy would reveal something far more dangerous than any American fleet—it would expose the fatal overconfidence growing within Japan’s own command.

As the officers took their places, Ugaki raised a small clipboard. His voice carried just enough authority to silence the low hum of conversation. He began to explain the rules of the exercise, though everyone knew them already. The table represented the Pacific theater. Each block of painted wood represented a ship—red for Japanese, white for American. Dice rolls determined the results of combat, with modifiers for visibility, range, and tactics. The simulation would unfold in phases, beginning with the diversionary attacks on the Aleutians, progressing to the bombardment and invasion of Midway itself, and concluding with the climactic carrier battle that would decide the war’s future.

In theory, the purpose of this exercise was to expose weaknesses in the plan before the real fleet set sail. In practice, however, it was little more than theater. Japan, by that spring, was riding the crest of a wave that had begun six months earlier at Pearl Harbor. No one in that room truly believed the plan could fail.

Japan in early 1942 was giddy with triumph. In six months, the Imperial Navy and Army had carved an empire across the Pacific, one that stretched from the Aleutian Islands in the north to the jungles of New Guinea in the south, from the shores of Burma to the coral reefs of the Solomons. Each conquest had been faster and bloodier than the last.

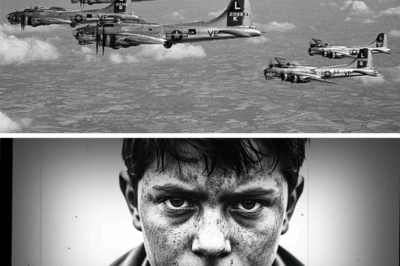

On December 7th, 1941, six Japanese aircraft carriers launched more than 350 planes at Pearl Harbor, crippling America’s Pacific Fleet. In less than two hours, eight U.S. battleships were either sunk or severely damaged. The attack killed over 2,400 Americans and shocked the world. But for Japan, it was only the beginning.

Within days, Japanese bombers had destroyed most of the American air power in the Philippines. Ten hours after Pearl Harbor, the skies over Clark Field were filled with fire and smoke. Two days later, Japanese aircraft hunted down and sank the British battleship Prince of Wales and the battlecruiser Repulse—a blow so devastating that British Prime Minister Winston Churchill later said it made his heart sink “like lead.” The myth of Allied naval invulnerability had been shattered.

Through the winter of 1941 and into early 1942, the Japanese empire seemed unstoppable. Hong Kong fell on Christmas Day. Manila surrendered on January 2nd. The mighty British fortress of Singapore collapsed on February 15th, its defenders—85,000 strong—taken prisoner. By March, the Dutch East Indies had fallen, and Japan gained access to the oil fields it had coveted for decades. In May, Burma was overrun, cutting off China’s last overland supply route.

At sea, Japan’s carrier forces reigned supreme. The Akagi, Kaga, Sōryū, and Hiryū—the same four carriers that had struck Pearl Harbor—had roamed the Pacific at will, launching raids as far west as the Indian Ocean. They had sunk the British carrier Hermes near Ceylon, bombed Colombo and Trincomalee, and forced the British Eastern Fleet to retreat all the way to Africa.

The Japanese Zero fighter, with its long range and unmatched maneuverability, ruled the skies. Allied pilots who survived their first encounter with it described it as flying against a ghost—quicker, sharper, and more agile than anything the Americans or British could put in the air. Japan’s military planners believed they had discovered the formula for invincibility.

They even had a name for this intoxicating belief: shōri-byō—“victory disease.” It was the assumption that success would repeat itself simply because it always had. It infected every level of command, from the Imperial Palace to the engine rooms of destroyers. And now, it hovered invisibly over the mess hall aboard Yamato as the war game began.

Rear Admiral Ugaki was both the referee and one of the chief architects of the plan. He had been Yamamoto’s right hand since before Pearl Harbor, his voice a constant presence in every major decision. He wanted the Midway operation to succeed—not just for Japan, but for his own legacy. The role of umpire required impartial judgment, but impartiality was the one thing Ugaki could not afford.

The first day of the simulation unfolded without issue. Wooden ships advanced across the blue expanse of the map in neat formation. Japanese forces moved swiftly, predictably, as the plan dictated. The Aleutian diversion proceeded smoothly. The invasion force advanced toward Midway right on schedule. The carrier fleet under Vice Admiral Chuichi Nagumo launched strikes against the island, bombarding its airfields into silence—or so the dice decreed.

When the umpires rolled to determine combat results, the outcomes consistently favored Japan. When a roll suggested a Japanese ship might be damaged or sunk, Ugaki intervened. “The result seems exaggerated,” he’d say quietly, moving his hand across the table to reposition a block. “Let’s assume light damage.”

The game became less a test and more a confirmation of what everyone wanted to believe: that Japan was unbeatable.

Among those watching silently from the edge of the room was Vice Admiral Nobutake Kondō, commanding the invasion support group. He studied the map with a frown. Kondō was no fool. He saw the cracks forming beneath the surface of this perfect plan.

He raised concerns about the logistics. Even if Japan captured Midway, how would they hold it? The atoll was 1,400 miles from the nearest Japanese base, and resupplying it would require a constant flow of convoys vulnerable to American submarines. The operation was audacious, yes—but audacity without sustainability was suicide.

Ugaki acknowledged his point with a polite nod. “Resupply will be difficult,” he admitted. “But manageable.” Then he turned to another officer and moved on. Kondō’s objections were recorded in the official minutes but ignored in practice.

Vice Admiral Nagumo, the man who had led the attack on Pearl Harbor, remained quiet through it all. He knew he was under scrutiny. Yamamoto’s staff had never forgiven him for not launching a third strike against Pearl Harbor’s fuel depots, and every hesitation he showed now was taken as weakness. Nagumo kept his doubts to himself.

By the end of the first day, Japanese victory seemed inevitable. The officers relaxed, trading quiet compliments and lighting cigarettes. But on the second day, everything changed.

The scenario had advanced to the point where Nagumo’s carriers were striking Midway Island. Japanese aircraft had bombed the runways, fuel stores, and gun emplacements. The airfield appeared neutralized. Then the “American” side—a group of junior officers playing the role of the U.S. Navy—made an unexpected move.

Their pieces, representing three American carriers, advanced into range faster than Yamamoto’s staff anticipated. It was an aggressive maneuver, one that defied Japanese predictions. The umpires rolled the dice to simulate combat. The result was devastating: two of Japan’s four carriers were hit and burning.

For a moment, the room fell silent. Ugaki frowned, calculating. According to the dice and the rules, those carriers were lost. It was an outcome that would cripple Japan’s striking force before the main battle even began. The game should have stopped there, forcing the planners to confront the possibility that the Americans could, in fact, win.

Instead, Ugaki cleared his throat and made a ruling. “The umpires will reconsider,” he said. He leaned over the table, adjusted the dice, and announced that the American attack had been “overstated.” The hits were downgraded to light damage. The carriers remained in play.

No one challenged him. The officers around the table nodded, relieved. The game continued.

What none of them realized—or chose not to see—was that the dice had been right all along. The numbers had predicted disaster. The rules had spoken truth. But truth was unwelcome aboard Yamato that day.

The men in that smoke-filled room believed they were writing the future. They didn’t yet know they were replaying it. And as the second day of the war game came to an end, the tiny wooden models of the Akagi, Kaga, Sōryū, and Hiryū still stood proudly on the map—exactly as they would not, just one month later, when the real battle came.

The junior officer running the American side glanced at his notes, then back at the admirals across the table. For a fleeting moment, he wondered if anyone else could see it—the faint shadow of defeat, already written in the game’s outcome, waiting for history to catch up.

Continue below

At 9:30 in the morning on May 1st, 1942, Rear Admiral Mat Ugaki stood in the converted mess hall of the battleship Yamato, watching junior officers arranged wooden blocks on a massive game table that represented the Pacific Ocean. Around him, 20 senior admirals in dress uniforms filed into the room, each followed by staff officers carrying folders of operational plans.

They had come to play a war game to test the strategy that would win the Pacific War for Japan. The target was Midway Island, a tiny ATL,400 mi northwest of Hawaii. The plan was Admiral Isuroku Yamamoto’s masterpiece. Lure the American carriers into a trap, destroy them in a single decisive battle, and force the United States to negotiate peace.

It was brilliant, complex, and involved coordinating hundreds of ships across thousands of miles of ocean. The war game would expose any flaws before the real battle began, except the game was rigged from the start. Ugi was the chief umpire, the man who would interpret dice rolls and determine outcomes.

He was also Yamamoto’s chief of staff, the architect of much of the plan being tested. He had a vested interest in proving the operation would succeed. And when the DICE predicted disaster, he simply changed the rules. Japan in May of 1942 was drunk on victory. In 6 months, the Imperial Navy had conquered an empire stretching from the Aleutians to the Dutch East Indies. The string of successes seemed endless.

On December 7th, 1941, six Japanese carriers had struck Pearl Harbor, sinking or damaging eight battleships and killing more than 2400 Americans. 10 hours later, Japanese bombers destroyed most of the American Air Force in the Philippines on the ground. Two days after that, Japanese aircraft sank the British battleship Prince of Wales and battle cruiser Repulse off the coast of Malaya, proving that even the most powerful warships were vulnerable to air attack.

The conquests continued through the winter. Hong Kong fell on Christmas Day. Manila fell on January 2nd. The supposedly impregnable fortress of Singapore surrendered on February 15th with 85,000 British and Commonwealth troops taken prisoner.

The Dutch East Indies collapsed in March, giving Japan access to the oil fields it desperately needed. Burma fell in May, cutting the supply route to China and threatening India. The aircraft carriers Akagi, Kaga, Soryu, and Hiryu had struck across the Pacific without suffering a single loss. They had attacked Pearl Harbor, supported invasions across Southeast Asia, raided into the Indian Ocean, and sunk the British carrier Hermes off Salon.

Japanese pilots flew the Mitsubishi A6M0, the finest carrier fighter in the world. In the first 6 months of war, Zeros had dominated every opponent they faced. Allied pilots reported the Zero could outturn, outclimb, and outrange anything the British or Americans could put in the air. Japanese planners believed they were invincible.

Every operation had succeeded. Every battle had been won. The Americans and British seemed incapable of stopping Japanese forces anywhere. Military leaders in Tokyo spoke confidently of dictating peace terms within months. The idea that Japan might actually lose a major battle seemed absurd. They called it victory disease.

The assumption that success would continue simply because it had succeeded before. The refusal to acknowledge that the enemy might adapt, might learn, might get lucky. The overconfidence that comes from winning so many battles that you stop seriously considering you might lose the next one.

Victory disease infected Japanese planning at every level from junior officers to admirals to the highest levels of government. That disease infected the war games from the moment they began. The games took place over 4 days in early May aboard Yamato anchored at Hashiima in Japan’s inland sea. The ship was the largest battleship ever built.

72,000 tons of steel and firepower, mounting 9 18in guns that could hurl shells weighing more than a ton over 25 m, she was a floating symbol of Japanese naval might, and using her as the venue for the war games, sent a message about the importance of the operation being planned. The mess hall had been cleared of furniture and replaced with a scale model of the Pacific.

The table measured nearly 40 ft across, covered with a grided map showing Midway, Hawaii, and the vast ocean between them. Wooden blocks represented ships, each labeled with the name and type of vessel. Colored pins marked positions and movements. Dice determined combat results, introducing the element of chance that made war unpredictable. Multiple umpires sat around the table, each responsible for different aspects of the simulation.

They would roll dice, consult damage tables, calculate fuel consumption, and determine the outcomes of engagements. The war game was supposed to be comprehensive. It would simulate not just the carrier battle, but the entire operation. the diversionary attack on the Aleutian Islands, the movement of the invasion force toward Midway, the positioning of submarines to intercept American reinforcements, the bombardment of Midway by battleships, the landing of troops, the establishment of air bases on the captured island.

Every phase of the operation would be tested on the game table before a single ship left port. In theory, the purpose was to fight the battle on paper first, to find problems and fix them before real ships and real men faced real combat. Honest wargaming could reveal flaws in timing, expose logistical problems, identify tactical vulnerabilities. A good war game could save lives by preventing bad plans from being executed.

In practice, the games became a formality, a scripted exercise designed to validate a plan that senior officers had already approved. Nobody wanted to find problems. Everyone wanted confirmation that the operation would succeed exactly as designed. The war games had become a ritual, not a test.

Vice Admiral Chuichi Nagumo commanded the carrier strike force. The four carriers that would attack midway and engage the American fleet. Nagumo had led the Pearl Harbor attack. He was experienced, competent, and deeply aware that combined fleet headquarters did not trust him. Yamamoto’s staff had criticized Nagumo for not launching a third strike at Pearl Harbor, for not pursuing and destroying American carriers that had escaped the attack. Nagumo knew he was on thin ice.

So when the war games began, he stayed quiet, asked no hard questions, and raised no objections. Vice Admiral Nouake Condo commanded the invasion force, the transports and support ships that would land troops on Midway after the carriers had neutralized American defenses. Condo was more outspoken. He looked at the plan and saw problems immediately.

How would they resupply midway after capturing it? The island was 1,400 m from the nearest Japanese base. Supplying a garrison that far forward would require constant convoys vulnerable to submarine attack. If they could not keep Midway supplied, they would have to withdraw, making the entire operation pointless. Yamamoto’s staff admitted resupply might be difficult, maybe impossible. But the plan was already approved.

Condo’s concerns were noted and ignored. The first day of gaming proceeded smoothly. Japanese forces advanced according to schedule. American forces reacted exactly as predicted. Umpires rolled dice to determine combat results and consistently ruled in favor of Japanese forces. When DICE suggested Japanese losses, Ugaki intervened to reduce the damage or eliminate it entirely.

The critical moment came on the second day. The game scenario had progressed to the point where Nagumo’s carriers were attacking Midway Island. Japanese aircraft bombed the airfield while the carriers prepared for a follow-up strike. Then the American player, a junior officer whose name was never recorded, made an aggressive move.

He sent land-based bombers from Midway to attack the Japanese carriers while their own aircraft were away. In real combat, this was precisely the kind of opportunistic strike that could devastate a carrier force. Carriers are most vulnerable when their aircraft are in the air, when flight decks are crowded with armed and fueled planes preparing to launch or land.

A well-timed bombing attack on a carrier deck covered in aviation fuel and ordinance could create a catastrophic chain reaction. The umpire for this phase of the game was Lieutenant Commander Masatake Okumia, a carrier division staff officer. Following the rules, Okumia rolled dice to determine how many hits the American bombers scored on the Japanese carriers. The dice showed a nine.

According to the damage tables, nine hits meant two carriers sunk. Akagi and Kaga, the largest carriers in the strike force, were ruled destroyed. Ugi watched this result with visible displeasure. Two carriers sunk by land-based bombers. Impossible. He did not believe the Americans would be that aggressive. Even if they were, Japanese carriers could defend themselves. The Zeros would intercept the bombers.

Anti-aircraft fire would shoot down survivors. Maybe a few bombs would get through, but not enough to sink two carriers. Ugaki overruled the dice. He reduced the hits from nine to three. Kaga was still sunk, but Akagi was only damaged. Still operational. The game continued. Okumia was surprised, but said nothing. He was a left tenant commander.

Ugaki was a rear admiral and Yamamoto’s right hand. Objecting would accomplish nothing and might damage Okumia’s career. The other officers in the room watched this intervention and understood the message. The games were not designed to expose problems.

They were designed to confirm success, but even the reduced damage was too much for Ugaki to accept. Later in the games, when the scenario moved to the next phase of operations, the invasion of New Calonia and Fiji, Kaga mysteriously reappeared. The carrier that had been sunk hours earlier in game time was back on the board, ready to participate in the next operation. No explanation was given.

The umpire had simply decided that sinking Kaga was inconvenient to the overall plan. So Kaga would not stay sunk. This was not the only manipulation. Throughout the four days of gaming, whenever dice rolls suggested Japanese losses or setbacks, Ugaki intervened. Air combat results were adjusted in Japan’s favor. American forces behaved in ways that made them easy to defeat.

Scenarios that might expose flaws in the plan were ruled unrealistic and rerun until they produced acceptable results. The most revealing manipulation involved American carrier movements. In the actual plan, Yamamoto expected American carriers to sorty from Pearl Harbor after the attack on Midway began, racing to defend the island and walking into the trap Japanese forces had prepared.

But in the war games, the American player tried a different strategy. He sorted carriers early, positioning them near midway before the Japanese attack began, allowing them to strike first. This was exactly what would happen in the real battle one month later.

But in the game, Ugaki ruled this scenario impossible. The Americans could not possibly know the attack was coming. They could not position carriers in advance. The American player was forced to keep his carriers at Pearl Harbor until after the Japanese struck midway, exactly as Yamamoto’s plan assumed they would. One officer did speak up.

Commander Minoru Genda, one of the most brilliant carrier tacticians in the Japanese Navy, was troubled by the assumption that Americans would not sort early. Gender had planned the Pearl Harbor attack. He understood that Americans were capable of surprise and aggression.

He warned that if American carriers were already near Midway when the attack began, the entire operation could be in jeopardy. Gender’s concerns were acknowledged and dismissed. The plan assumed Americans would react, not anticipate. Changing that assumption would require redesigning the entire operation. Nobody wanted to do that. The games had already validated the plan. Questions were unwelcome.

By the end of 4 days, the war games had confirmed exactly what senior officers wanted. Confirmed. The Midway operation would succeed. American carriers would be destroyed. Japan would win a decisive victory that would force the United States to negotiate peace. Officers left the Yamato confident the plan was sound. The problem was that confidence was built on lies.

The first lie was that Japanese intelligence was reliable. In reality, American cryp analysts had broken the Japanese naval code designated JN25. Since early 1942, Commander Joseph Rosherfort and his team at station HYPO in Hawaii had been reading fragments of Japanese radio traffic.

By April, they knew Japan was planning a major operation against a target code named AF. Rashfor believed AF was Midway, but Washington disagreed. To prove his case, Rashfor devised a simple trick. He had the base at Midway send an unencrypted radio message reporting that their water distillation plant had broken down and the island was running short of fresh water.

It was a complete fabrication, but Japanese intelligence intercepted the message and fell for it. 2 days later on May 22nd, American codereers intercepted a Japanese intelligence report stating that AF was short of water. Roshapor had his proof. AF was midway. The Americans knew where the attack would come and roughly when it would happen.

Japan had no idea the Americans were reading their mail. The war games on Yamato proceeded on the assumption that strategic surprise was guaranteed, but surprise was already lost. The fundamental premise of Yamamoto’s plan was compromised before the first ship left port. The second lie was about American carrier strength.

At the Battle of Coral Sea in early May, Japanese and American carrier forces had fought the first naval battle in history where the opposing ships never cighted each other. All the fighting was done by aircraft. The battle was part of Japan’s operation to capture Port Moresby in New Guinea, which would threaten Australia and extend Japanese control over the South Pacific.

The battle lasted two days. On May 7th, American aircraft sank the light carrier. On May 8th, both sides launched major strikes. Japanese aircraft damaged the carrier Yorktown and delivered devastating attacks on Lexington. Multiple torpedo and bomb hits set Lexington ablaze.

Despite heroic damage control efforts, fires reached the aviation fuel storage, triggering massive explosions. The crew abandoned ship and Lexington was scuttled by American destroyers. Japan lost the light carrier Sho and suffered damage to the fleet carrier Shokaku severe enough to put her out of action for months. Another fleet carrier, Zuiaku, lost so many aircraft and pilots that she could not participate in the midway operation even though the ship itself was undamaged. Japanese intelligence assessed Yorktown as sunk alongside Lexington. Pilots reported seeing both

American carriers burning and dead in the water. The assessment seemed reasonable, but the reality was different. Yorktown had taken a single bomb hit that penetrated deep into the ship before exploding, but skilled damage control had contained the damage. The ship limped away from the battle, trailing oil, but still under power.

Japanese intelligence concluded that only two American carriers remained operational, Enterprise and Hornet. The Midway plan was built around facing two carriers. A force Japanese planners believed their four carriers could easily defeat. The math seemed simple. Four carriers against two experienced Japanese pilots against inexperienced Americans.

Superior Japanese aircraft against inferior American planes. Victory seemed certain. In reality, Yorktown had not sunk. The ship limped back to Pearl Harbor with a massive hole in the flight deck and structural damage that would normally require 3 months in a shipyard to repair. A 551-lb bomb had penetrated through six decks before exploding above the forward engine room.

The explosion destroyed six watertight compartments, killed 66 men, wrecked the elevator machinery, disabled the radar and refrigeration systems, and opened seams along 30 hull frames. Fuel oil leaked into the ocean, leaving a slick that stretched for miles behind the ship. Rear Admiral Aubry Fitch, who inspected the damage during the voyage back to Hawaii, estimated repairs would take 90 days under normal circumstances, but Admiral Chester Nimttz, commander of the Pacific Fleet, did not have 90 days.

Station HYPO, had broken the Japanese codes. Rashford’s team knew the Japanese were planning a major operation. They knew the target was Midway. They knew the approximate date of the attack. Nimttz needed every carrier he could put to sea.

He could not afford to leave Yorktown in dry dock while the battle was fought. But Admiral Chester Nimitz, commander of the Pacific Fleet, did not have 90 days. He ordered Pearl Harbor’s repair crews to do the impossible. When Yorktown arrived on May 27th, one day ahead of schedule, Nimmits cut orders, voiding safety regulations. Normally, the ship would spend a full day purging aviation fuel from storage tanks before entering dry dock.

Nimttz ordered the ship into dry dock number one immediately with fuel still aboard. More than 1,400 shipyard workers swarmed over Yorktown. They worked around the clock for 72 hours straight, welding steel plates, patching holes, restoring systems, rolling blackouts across Aahu provided electricity for the massive welding effort.

On May 30th, 3 days after entering port, Yorktown put to sea with some repair crews still aboard finishing work as the ship headed for battle. The ship was not fully repaired, but it was operational. Japan would face three carriers, not two. The third lie was about timing. Yamamoto’s plan assumed American carriers would not sort until after the attack on Midway began.

The carriers were supposedly at Pearl Harbor, nearly 1,400 m away. Even if they raced to Midway at maximum speed the moment the attack started, they could not arrive until the second or third day of battle. By then, Japanese forces would have captured the island and would be waiting in prepared positions. But Nimitz knew when the attack was coming.

He sent Enterprise, Hornet, and Yorktown to sea days before the Japanese fleet arrived, positioning them northeast of Midway at a predetermined rendevu point called Point Luck. On the morning of June 4th, when Nagumo’s carriers launched their attack on Midway, American carriers were already in position 200 miles away, waiting to strike.

The real battle began exactly 1 month after the war games ended. At 0430 on June 4th, 1942, Nagumo launched the first strike against Midway. 36 dive bombers, 36 torpedo bombers, and 36 zero fighters headed for the island, while the carriers prepared a second wave armed with torpedoes to attack American ships if they appeared.

At the same time, Nagumo launched seven reconnaissance aircraft to search for American forces, but the search was poorly organized. Too few aircraft covering too much ocean, flying in bad weather, taking off late due to mechanical problems. One scout from the cruiser tone was delayed by 30 minutes. A delay that would prove catastrophic. The attack on Midway caused damage but failed to neutralize the island’s defenses.

The strike leader radioed back that a second attack was necessary. Nagumo made the decision that would doom his fleet. He ordered the second wave of aircraft, which were armed with torpedoes for attacking ships, to be rearmed with bombs for attacking land targets.

Deck crews went to work removing torpedoes, bringing planes down to the hanger deck, swapping weapons, bringing planes back up. It was organized chaos, and it left the carriers vulnerable. At 0728, one of Nagumo’s scouts finally reported cighting American ships. The message was vague, giving no indication of whether carriers were present. Nagumo hesitated. Should he continue rearming for a second strike on midway or should he prepare to attack American ships? He ordered the rearming to stop, then changed his mind again when a follow-up message confirmed American carriers were present. Now he needed to rearm again, putting torpedoes

back on aircraft that had just had bombs loaded. More time lost, more confusion. By midm morning, Nagumo’s flight decks were covered with armed and fueled aircraft, ammunition, and ordinance. Exactly the scenario the war games should have identified as dangerous.

Exactly the situation Okumia’s dice roll had predicted. But because Ugaki had dismissed that scenario as unrealistic, no precautions had been taken. American attacks began at 0930. Torpedo bombers from Hornet Enterprise and Yorktown pressed home their attacks with suicidal courage. The obsolete Douglas TBD Devastator was slow and poorly armed.

The aircraft had a maximum speed of just 115 mph when carrying a torpedo, making it an easy target for the faster, more maneuverable Zeros. Japanese fighters slaughtered them. Torpedo Squadron 8 from Hornet attacked first. 15 Devastators led by Lieutenant Commander John Waldron flew directly toward the Japanese carriers without fighter escort.

Waldron had told his pilots before taking off that if only one aircraft survived to launch its torpedo, the mission would be a success. His prediction was horrifyingly accurate. Zeros swarmed the slowmoving torpedo bombers. One by one, the Devastators were shot down. Some crashed in flames, others broke apart in midair. A few managed to release their torpedoes before being hit.

But the weapons ran too slow and the Japanese carriers easily avoided them. All 15 aircraft were destroyed. Only Ensign George Gay survived, floating in the ocean for 30 hours, watching the battle rage around him, hiding under his seat cushion when Japanese ships passed close by. Torpedo squadron 6 from Enterprise attacked next.

14 Devastators approached from a different angle. The result was the same. Zeros pounced on them. Anti-aircraft fire filled the sky. 10 of the 14 aircraft were shot down. Not one torpedo hit. Then came torpedo squadron. Three from Yorktown. The only squadron that had fighter escort. Even with wildcat fighters trying to protect them, 12 of 13 Devastators were destroyed. The carnage was almost complete.

Of 41 devastators that attacked, only six survived. Not a single torpedo hit. The sacrifice seemed meaningless. The pilots and gunners who flew those missions knew they were likely flying to their deaths, but they pressed their attacks anyway. Some were so low their propellers kicked up spray from the ocean.

Some were so close to the Japanese carriers that they could see sailors on deck running to battle stations. The torpedoes they carried were obsolete. Mark1 13 models that ran too slow, ran too deep, and often failed to explode even when they hit.

But the crews attacked anyway, knowing their chances of survival were almost zero, hoping their sacrifice would create an opening for someone else. But the torpedo attacks drew Japanese fighters down to low altitude and scattered the combat air patrol across miles of ocean. The carriers were exposed and high above, invisible to Japanese lookouts focused on the torpedo bombers below. Dive bombers from Enterprise and Yorktown were beginning their attack runs.

Lieutenant Commander Wade McCcluskey from Enterprise had been searching for the Japanese fleet for over an hour, burning fuel his squadron could not spare. At 10:00, running low on fuel and considering turning back, McCcluskey made a critical decision. He spotted the Japanese destroyer Arashi racing northeast to rejoin the fleet.

After hunting for the American submarine Nautilus, McCcluskey followed the destroyer’s wake. At 10:22, McCcluskey led 37 Douglas SBD Dauntless dive bombers from Enterprise into a nearly vertical dive toward a Kagi and Kaga. 2 minutes later, Lieutenant Commander Maxwell Leslie led 17 more Dauntlesses from Yorktown towards Soryu. The Japanese carriers had no warning.

Their fighters were at sea level chasing torpedo bombers. Their anti-aircraft gunners were focused downward. Nobody saw the dive bombers until bombs were already falling. The attack took 5 minutes. In those five minutes, the course of the Pacific War reversed. Kaga took four bomb hits. The first penetrated the flight deck near the forward elevator.

The next three straddled the midship elevator. All four bombs detonated among aircraft being rearmed on the hanger deck. Aviation fuel ignited. Torpedoes exploded. Ammunition cooked off. Within minutes, the interior of the carrier was an inferno. Firefighting efforts failed. 800 men died. The crew abandoned ship. Kaga sank that evening.

Akagi took only one bomb hit, striking the flight deck near the midship elevator. But the damage was catastrophic. The bomb detonated among armed aircraft waiting to launch. Fuel and ordinance exploded in a chain reaction that gutted the ship. Fires spread faster than damage control teams could fight them. The bridge filled with smoke. Nagumo was forced to transfer his flag to the light cruiser Nagara.

Akagi burned through the night and was scuttled the next morning by Japanese destroyers. Soryu took three hits in as many minutes. The first blasted the flight deck forward of the elevator. The next two struck near the midship elevator. Like Kaga and Akagi, Soru’s hanger deck was packed with armed aircraft and ordinance.

The bombs triggered explosions that tore the ship apart. Soryu sank that evening, taking 700 men with her. Three carriers destroyed in 5 minutes. Exactly what the DICE had predicted in the war games. Exactly what Ugaki had ruled impossible. Hiru, the fourth carrier, was operating separately and escaped the initial attack.

Admiral Tamon Yamaguchi, Hiru’s commander, immediately launched a counterattack against the American carriers. His aircraft found Yorktown and put three bombs into her at noon. Damage control crews worked miracles. Within two hours, Yorktown was steaming at 19 knots and recovering aircraft. Japanese pilots returning from a second strike thought they were attacking a different undamaged carrier.

They put two torpedoes into Yorktown’s port side at 4:20 in the afternoon. This time, the damage was too severe. The ship lost all power and developed a 23° list. Captain Elliot Buckmaster ordered abandoned ship. Later that afternoon, dive bombers from Enterprise found Hiru and hit her with four bombs. Like the other carriers, Hiru was doomed by fires and induced explosions.

She sank the next morning. Admiral Yamaguchi chose to go down with his ship. By the end of June 4th, Japan had lost all four carriers that had participated in the attack on Pearl Harbor. Approximately 3,000 Japanese sailors and pilots were dead, including many of the most experienced and highly trained aviators in the fleet.

The carriers could eventually be replaced. The pilots could not. It took years to train a carrier pilot to the skill level Japan had lost in a single day. The United States lost Yorktown, finally sunk by the Japanese submarine I168 on June 7th, and the destroyer Haman. Total American casualties were 307 men, a devastating exchange ratio.

Japan had gambled everything on a decisive battle and lost catastrophically. The battle turned on timing measured in minutes and decisions made in seconds. If Tone’s scout plane had launched on time instead of 30 minutes late, Nagumo would have known about American carriers earlier and might have prepared differently.

If American dive bombers had arrived 10 minutes earlier or 10 minutes later, Japanese fighters would have been in position to intercept them. If Nagumo had not changed his mind about rearming his aircraft, his flight decks would not have been covered with explosives when the bombs fell.

But the deeper cause of the disaster was the overconfidence built during those four days of war games on Yamato. Because Ugaki had overruled the dice, Japanese planners never seriously considered what would happen if carriers were attacked while rearming aircraft because the games assumed Americans would not sort early. No provisions were made for detecting American carriers before they struck. Because uncomfortable scenarios were dismissed as unrealistic, the Japanese fleet sailed into battle unprepared for exactly the situation they encountered. The man who played the American side in the war games. The unnamed junior

officer who sent land-based bombers against Japanese carriers while they were vulnerable had predicted the battle more accurately than Japan’s senior admirals. But nobody listened to him because the scenario was ruled impossible by an umpire who refused to accept that Japan might lose. Japan tried to conceal the scale of the disaster. Radio Tokyo announced a great victory at Midway.

The Japanese public was told that American forces had been driven back with heavy losses. No mention was made of the four carriers. Casualty lists were not published. For months, Japanese newspapers reported that Akagi, Kaga, Soryu, and Hiryu were still operating with the fleet.

Wounded survivors were quarantined in hospitals and forbidden to speak about what happened. Junior officers who had witnessed the battle were transferred to remote posts with orders never to discuss midway. The ships were kept on the active roster, listed as deployed but unavailable. When families inquired about crew members who had died, they were told only that their loved ones had fallen in action, no details were provided about where or how.

The deception was so complete that many Japanese citizens did not learn the truth until after the war ended. Even within the military, only senior officers knew the full extent of the defeat. Replacement pilots training for carrier operations were told their predecessors had been reassigned, not killed. Strategic planning continued as though four firstline carriers were available for deployment.

The cover up served a short-term political purpose, preventing damage to morale and preserving confidence in military leadership, but it also prevented learning from failure. If junior officers did not know what happened at midway, they could not develop tactics to prevent it from happening again. If planners did not acknowledge the defeat, they could not analyze what went wrong.

The same overconfidence that infected the war games continued to infect Japanese strategy through the remainder of the war. The strategic consequences were immediate and catastrophic for Japan. Japan’s entire war strategy had always depended on winning quickly before American industrial might could fully mobilize. The plan was to seize a defensive perimeter across the Pacific, fortify it, and make any American counteroffensive so costly that Washington would negotiate a peace settlement that left Japan in control of its conquests. Midway was supposed to be

the decisive battle that would destroy American carrier power and force that negotiation. When the knockout blow failed, when the four carriers sank instead of achieving victory, Japan’s strategic position became hopeless. The defensive perimeter was incomplete. American carriers remained a threat.

And now Japan had lost four fleet carriers, over 300 aircraft, and nearly 3,000 trained personnel, including irreplaceable veteran pilots. The losses could not be made good in time to matter. American forces began offensive operations at Guadal Canal in August of 1942, barely 2 months after midway. The landing caught Japan by surprise. For 6 months, both sides poured resources into the struggle for the island and the surrounding waters.

Japan fought desperately to hold Guadal Canal. But without carrier superiority, every battle became harder. The naval battles around Guadal Canal throughout late 1942 and early 1943 cost Japan two more carriers, Ryujo and Hio, along with hundreds more irreplaceable pilots. Cruisers and destroyers fought savage night battles in Iron Bottom Sound, where so many ships were sunk that the seafloor was carpeted with wreckage.

Meanwhile, American shipyards were launching new carriers at an astonishing rate that Japanese planners had not believed possible. The Essexclass fleet carriers were massive ships, displacing 36,000 tons, capable of carrying nearly 100 aircraft, and built to take punishment. The first Essexclass carrier joined the fleet in December of 1942, less than 6 months after midway. More followed at intervals of just a few months.

By mid 1944, the United States had more fleet carriers in the Pacific than Japan had possessed at the start of the war. Escort carriers built on merchant ship hulls using mass production techniques came off production lines even faster. These smaller carriers could not match fleet carriers in aircraft capacity or speed, but they could provide air cover for convoys, support amphibious landings, and hunt submarines.

American shipyards launched escort carriers at a rate of one every few weeks. By 1944, the United States Navy had more than 100 escort carriers in service. The industrial capacity that had seemed irrelevant in May of 1942 became decisive by 1944. American factories produced aircraft by the tens of thousands.

In 1944 alone, American industry built nearly 100,000 aircraft of all types. Training programs graduated new pilots by the hundreds every month. The United States had enough productive capacity that damaged ships were repaired in weeks instead of months. Lost aircraft were replaced faster than they could be shot down.

And pilot losses could be made good from a seemingly inexhaustible pool of trained aviators. Japan could not match this production. The industrial base was smaller. Resources were scarcer. Shipyards struggled to complete new carriers against competing demands for steel, labor, and resources. Aircraft factories operated under constant threat of air attack as American bombers reached deeper into Japanese territory.

The pilot training program, already strained by combat losses, could not replace losses fast enough while maintaining quality standards. By the battle of the Philippine Sea in June of 1944, Japanese carrier air groupoups were staffed with inexperienced pilots who stood no chance against veteran American aviators. The result was a massacre the Americans called the great Mariana’s Turkey Shoot.

Ugi survived midway, though his reputation suffered quietly within circles that knew the truth. He continued serving as Yamamoto’s chief of staff through 1943. In April of 1943, American P38 fighters guided by decoded Japanese radio traffic intercepted and shot down Yamamoto’s aircraft over Bugenville.

Ugaki was on the same flight but survived the crash with severe injuries. After months of recovery, Ugaki commanded battleship divisions and shore bases. He kept a detailed diary throughout the war. The diary reveals a man conflicted between loyalty to the plan he helped create and growing awareness that the war was lost. He acknowledged mistakes but never fully accepted responsibility for the war games that validated a flawed strategy.

On August 15th, 1945, Japan surrendered. Emperor Hirohito announced the decision in a radio broadcast heard across the nation. The next day, Ugaki led a final unauthorized kamicazi mission, flying a bomber toward American ships off Okinawa. He died in the attack, one of the last casualties of the war he helped prolong through overconfidence and wishful thinking.

The story of the rigged war games remained hidden for years. Japanese military records were destroyed or classified. Officers who participated either died in combat or stayed silent. The first public account came from Captain Mitsuo Fuida and Commander Masatake Okumia in their book published in 1955, Midway, the battle that doomed Japan.

Fuida had led the air attack on Pearl Harbor and was aboard Akagi during Midway. Okumia was the umpire whose dice roll Ugaki had overruled. Their book described the war games in detail, including Ugaki’s intervention when the dice predicted disaster. The account shocked readers in both Japan and America. Here was evidence that Japan’s military leadership had known the plan was flawed, but proceeded anyway.

Some historians later questioned specific details, noting that Fukida occasionally exaggerated events. But the core facts remained undisputed. Ugi did intervene to reduce predicted Japanese losses. The games did validate a flawed plan. Japan did sail into disaster despite warnings that went unheeded. Modern wargaming doctrine treats the Midway games as a cautionary example.

Professional military education uses the story to illustrate confirmation bias, the tendency to seek information that validates existing beliefs and ignore information that challenges them. War games are supposed to expose problems, not hide them. Empires must enforce rules impartially, not adjust results to produce desired outcomes. The United States learned opposite lessons from the same battle.

American war games before Midway had been rigorous and honest, exposing multiple ways operations could fail. When Nimitz planned the defense of Midway, he knew from gaming exercises that carrier battles could turn on tiny margins of timing and position. He positioned his forces to maximize surprise while minimizing exposure.

Rashfor’s codereing gave Americans information advantage, but information alone does not win battles. Americans still had to make correct decisions based on that information. They had to position carriers precisely, time attacks perfectly, and execute tactics flawlessly. The 5 minutes that destroyed three Japanese carriers required months of preparation, training, intelligence gathering, and realistic assessment of capabilities.

Japan had advantages of a larger fleet, more experienced pilots, and superior aircraft. But Japan also had overconfidence, rigid planning, and leadership unwilling to question assumptions. When the dice predicted disaster during the war games, Ugaki changed the dice. instead of changing the plan. When reality proved the dice were right, it was too late.

The lesson extends beyond military strategy and speaks to fundamental problems in organizational decision-making. Any organization facing complex challenges must honestly assess risks and welcome bad news. The moment an organization starts believing its own propaganda, starts dismissing uncomfortable data because it contradicts desired outcomes, starts punishing messengers who deliver warnings, that organization is heading for disaster.

Leaders who punish messengers for delivering uncomfortable truths, guarantee those truths will be hidden until disaster strikes. In the Japanese military hierarchy of 1942, junior officers knew that questioning senior officers could end careers. Okuma watched Ugaki overrule the dice and said nothing because speaking up would have accomplished nothing except damaging his own prospects.

How many other officers noticed problems but stayed silent for the same reason? How many valid concerns were never raised because the culture discouraged dissent? Tests and simulations that always validate existing plans are worthless. The entire point of testing is to find failure modes before they matter.

A test that cannot fail is not a test at all. It is theater. The Midway War games were theater, a performance designed to create the appearance of rigorous planning while actually just confirming what senior officers had already decided. The dice were props. The game table was a stage. And when the props produced the wrong result, they were simply adjusted until they produced the right one.

Modern organizations repeat these mistakes constantly. Corporations run marketing tests designed to confirm that new products will succeed. Government agencies conduct studies designed to justify decisions already made. Military commands run exercises designed to validate existing doctrine. In each case, the simulation becomes kabuki theater, not honest assessment.

And when reality intervenes, when the product fails or the policy backfires or the doctrine proves wrong, everyone acts surprised. The warning signs are always the same. When challenging questions are discouraged, when devil’s advocates are seen as disloyal, when best case scenarios are treated as most likely outcomes, when pessimistic forecasts are dismissed as negativity, when tests are designed to pass rather than to reveal problems.

These are symptoms of the same disease that infected Japanese planning in 1942. If Ugaki had accepted the dice roll, if he had allowed two carriers to remain sunk in the war game, Japanese planners might have recognized the vulnerability of carriers rearming aircraft under combat conditions. They might have developed procedures for rapid launch that kept flight decks clear.

They might have positioned carriers with more separation so one attack could not hit multiple ships. They might have improved reconnaissance to detect American carriers earlier. They might have questioned whether the entire operation was worth the risk given the possibility of heavy losses. None of those improvements were made because the war game hid the problem.

The plan sailed forward with a fatal flaw that everyone should have seen, but nobody acknowledged because acknowledging it would have required admitting the plan was flawed, which would have required changing the plan, which would have required senior officers to admit they had been wrong. Pride, institutional inertia, and fear of losing face combined to send the Japanese fleet into disaster.

Instead, Japan sailed to Midway, confident the plan would succeed because a rigged game said it would. The DICE had predicted the truth. The admirals rejected the truth. And in 5 minutes on June 4th, reality proved the dice were right. Four carriers burned. 3,000 men died. Japan’s offensive capability in the Pacific was shattered.

All because an empire looked at an uncomfortable result and decided to change it rather than accept it. Today, the wrecks of Akagi, Kaga, Soryu, and Hiyu rest in more than 17,000 ft of water northwest of Midway. Deep sea surveys have photographed the carriers where they fell. Akagi lies upright with her bow broken off. Kaga rests inverted, her hull shattered by the explosions that destroyed her.

Soryu and Hiru are scattered across miles of ocean floor. They remain war graves, protected by international agreement, visited only by remotely operated vehicles that document their condition for historical research. The battles fought in those 5 minutes are studied in every naval academy in the world. The decisions made by Nagumo, Spruent, and Fletcher are dissected in command courses.

The intelligence work by Roshaphor is taught as the gold standard of signals analysis. The sacrifices of the torpedo bomber crews are honored as examples of courage under impossible odds. But the story of the war games teaches a different lesson. It shows what happens when leaders value certainty over truth.

When uncomfortable predictions are dismissed rather than addressed. When tests are designed to confirm rather than challenge, Ugaki rolled the dice, saw disaster, and decided disaster was impossible. Reality disagreed. The dice were right. The admiral was wrong, and four carriers burned because confidence mattered more than truth.

News

CH2 Wehrmacht Major Fled the Eastern Front — 79 Years Later, His Buried Field Chest Was Found in Poland

Wehrmacht Major Fled the Eastern Front — 79 Years Later, His Buried Field Chest Was Found in Poland It…

CH2 Why German Infantry Feared the 101st Airborne More Than Any Other Division

Why German Infantry Feared the 101st Airborne More Than Any Other Division June 6th, 1944. 02:15 hours. Sainte-Mère-Église, Normandy….

CH2 How One Woman Exposed the Hidden Gun That Shot Down 28 Planes in 72 Hours at Iwo Jima

How One Woman Exposed the Hidden Gun That Shot Down 28 Planes in 72 Hours at Iwo Jima February…

CH2 The 96 Hour Nightmare That Destroyed Germany’s Elite Panzer Division

The 96 Hour Nightmare That Destroyed Germany’s Elite Panzer Division July 25th, 1944. 0850 hours. General Leutnant Fritz Berlin…

CH2 One Of Many Unsung Heroes – The 13-Year-Old Boy Who Guided Allied Bombers to Target Using Only a Flashlight on a Rooftop

One Of Many Unsung Heroes – The 13-Year-Old Boy Who Guided Allied Bombers to Target Using Only a Flashlight on…

CH2 June 4, 1942 At 10:30 AM: The Five Minutes That Destroyed Japan’s Chance Of Winning WW2

June 4, 1942 At 10:30 AM: The Five Minutes That Destroyed Japan’s Chance Of Winning WW2 June 4th, 1942,…

End of content

No more pages to load