Japan Never Expected B-25 Eight-Gun Noses To Saw Ships Apart

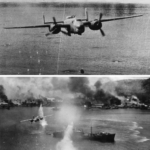

Bismarck Sea, March 3rd, 1943. At precisely 0600 hours, the sea stretched calm and deceptively serene under a wash of golden morning light. From the bridge of his flagship, Rear Admiral Masatomi Kimura squinted through his binoculars, scanning the horizon where the convoy’s formation carved a gray trail of exhaust against the blue. The rhythmic thrum of diesel engines echoed through the steel hull, steady and confident. Eight destroyers shepherded eight fully loaded transport ships toward the coast of New Guinea, carrying the 51st Division’s reinforcements — 6,900 soldiers and everything they needed to sustain Japan’s fight in the region. To Kimura, it felt routine. He had commanded similar convoys before, and the Imperial Japanese Navy had sailed these waters for over a year without serious interference from the Americans.

The war, as Kimura saw it, still belonged to Japan. Their ships ruled the western Pacific, their air power reached far from Rabaul, and their enemies — even after Guadalcanal — were still learning how to fight in these waters. American bombers had harassed convoys before, but they were high-altitude nuisances. The lumbering B-17 Flying Fortresses came from so far away that their bombs, dropped from five miles up, landed everywhere but on target. Japanese destroyers had learned to zigzag through the explosions, riding the concussions like waves. The American airmen, Kimura believed, lacked the skill to challenge Japan’s navy at sea.

He had reason to feel confident. The convoy he now commanded carried more than men and supplies — it carried proof that Japan could still reinforce its island strongholds. The eight transports were laden with ammunition, food, field equipment, and radio supplies bound for Lae. Their escorts — destroyers Shirayuki, Arashio, Asashio, Tokitsukaze, Yukikaze, Shikinami, Asagumo, and Uranami — formed a disciplined shield around them, weaving through the sea in tight formation. Each destroyer’s crew knew its role, and every officer aboard trusted in Japan’s well-tested naval doctrine.

What Kimura could not possibly know, what not even his intelligence officers at Rabaul could imagine, was that over the past few months, American mechanics working out of dusty hangars in Australia had reimagined how air warfare against ships was fought. They had taken a conventional medium bomber — the North American B-25 Mitchell — and, through a series of improvised modifications, turned it into something the Japanese navy had no defense against. Within four hours, that innovation would transform this tranquil patch of ocean into a killing ground.

The transformation had not come from high command or Washington planners. It had come from frustration — and from a handful of pilots and engineers unwilling to accept failure. For over a year, American crews had tried every known method of bombing Japanese shipping in the Southwest Pacific, and almost all of them failed. High-altitude bombing was useless against moving ships; torpedo runs required long, suicidal approaches that made the aircraft easy targets; and medium-altitude bombing gave ships too much time to evade. Something had to change.

The Japanese had grown complacent precisely because of that failure. Convoy commanders like Captain Tameichi Hara, who commanded the destroyer Shigure, knew every tactic the Americans used. He had seen B-17s lumber overhead, dropping their bombs in neat, predictable strings that fell harmlessly into the sea. He had watched torpedo planes make their approach, only to be cut down by the tight web of anti-aircraft fire from destroyers. Japan’s anti-aircraft doctrine had become refined through these experiences — the combination of disciplined fire, coordinated evasive maneuvers, and fighter support from Rabaul had been enough to repel nearly every Allied attack so far.

Every destroyer in Kimura’s convoy bristled with guns. The layered defense was formidable: 12.7-centimeter dual-purpose guns for heavy fire, rapid-firing 25-millimeter autocannons for close defense, and scores of 13-millimeter machine guns to sweep the skies. Commanders like Lieutenant Commander Yasumi Doi on the Tokitsukaze had drilled their gunners relentlessly to maintain steady, precise fire even under attack. Japanese manuals described this defensive curtain as a “steel umbrella.” It had saved convoys time and again, and everyone on board believed it would hold again today.

The transports themselves carried far more than troops. Each vessel’s hold was packed tight with crates of ammunition, fuel drums, field radios, and medical supplies — everything needed to sustain Japan’s garrisons along the northern coast of New Guinea. The largest, the Kyokusei Maru, displaced over 6,000 tons and carried a full regiment. Below decks, soldiers sat shoulder to shoulder, playing cards, smoking, or sleeping against their rifles. Many had waited at Rabaul for weeks, delayed by weather and the ever-present risk of submarine attack. When the order to sail finally came, they boarded with relief.

The Japanese formation was precise — destroyers at the periphery, transports clustered tightly at the center. They moved through the calm sea in neat columns, the morning light glinting off the wakes trailing behind them. Every man aboard knew that American aircraft were active in the area, but that knowledge had long ceased to cause panic. The convoy commanders had weathered American attacks before. They expected another futile attempt by high-flying bombers — a show of strength that would, once again, fail to stop them.

But the Americans watching from afar that morning had something entirely different in mind.

At a dusty Australian airfield near Brisbane, months earlier, a maverick officer named Major Paul “Pappy” Gunn had been quietly rewriting the rules of air combat. Gunn, a former Navy pilot turned Army Air Forces officer, had grown tired of watching his men die in missions that achieved nothing. He had seen too many B-25s return riddled with holes after missing their targets entirely. The problem, as he saw it, wasn’t the pilots — it was the airplanes. The B-25 Mitchell had potential: fast, sturdy, and versatile. But in its standard configuration, it simply wasn’t built to kill ships.

So Gunn decided to rebuild it.

Working alongside North American Aviation’s field representative Jack Fox at Eagle Farm Airfield, Gunn began stripping B-25s down to their frames and reengineering their noses. He removed the bombardier’s compartment and replaced it with raw firepower — first four, then six, and eventually eight .50-caliber Browning machine guns, all fixed forward. To balance the added weight, he reinforced the fuselage, redistributed ammunition storage, and recalibrated the aircraft’s center of gravity. The results were crude, improvised, and devastatingly effective.

Each of those eight guns fired armor-piercing incendiary rounds — the M8 API — at nearly 3,000 feet per second. One gun could fire 850 rounds a minute. Eight together unleashed nearly 7,000 rounds every sixty seconds — a hurricane of lead that could shred the superstructure of a destroyer, obliterate anti-aircraft positions, and turn open decks into slaughterhouses. For the Japanese crews who would face them, it was like staring down a mechanized dragon breathing fire. Survivors of later encounters would recall the horror of watching a B-25’s nose erupt in blinding flashes as hundreds of tracer rounds stitched their ships from bow to stern.

Gunn’s innovation didn’t stop there. Working with Major William Benn of the 43rd Bombardment Group, the Americans perfected a new tactic to go with their modified aircraft: skip bombing. Benn discovered that bombs dropped at just the right speed and altitude could skip across the surface of the water — like a stone skimming across a pond — and slam into the side of a ship before exploding. It demanded precision and nerves of steel. Pilots had to fly at treetop level — or, over the ocean, wave-top height — directly into a wall of anti-aircraft fire. One mistake meant disintegration. But if executed correctly, a single bomb could cripple or sink a transport outright.

General George Kenney, commander of the Fifth Air Force, immediately saw the potential. The combination of heavy nose-mounted guns and skip bombing created a new kind of weapon: the “commerce destroyer.” It was fast, deadly, and, most importantly, it didn’t rely on altitude or luck. By early 1943, the 3rd Attack Group had been fully converted into this new role, its squadrons of modified B-25s — nicknamed “strafers” — training daily against shipwrecks near Port Moresby, learning to judge distance and timing to perfection.

Now, those same aircraft were on their way to meet Admiral Kimura’s convoy.

Back aboard the Japanese ships, the morning passed uneventfully until just after sunrise, when a lookout aboard the destroyer Asashio spotted dark shapes approaching from the south. Through his binoculars, Lieutenant Commander Aikawa saw what appeared to be a familiar sight — American bombers at medium altitude, perhaps 7,000 feet, flying in the predictable formation of B-17s and B-25s. He ordered his men to action stations. The anti-aircraft guns swiveled upward, their barrels tracking the approaching specks.

The Japanese officers felt calm — even confident. This was the kind of attack they had practiced for. The enemy would drop bombs from too high to be accurate, the destroyers would zigzag, the gunners would fill the sky with tracers, and, once again, the convoy would survive.

But what they couldn’t see — not yet — were the other aircraft flying below the horizon, hugging the waves.

Coming in fast, barely twenty feet above the water, were the modified B-25 Mitchells of the 90th Bombardment Squadron. Their pilots could already see the faint silhouettes of Japanese destroyers against the sunlight. Each aircraft’s nose was bristling with eight machine guns, gleaming like a predator’s teeth.

The Japanese lookouts still thought the real attack was coming from above. They didn’t realize that the threat below — the glint of wings against the sea — was something entirely new, something designed specifically to break every rule they had trusted until now.

And as the first American aircraft dropped to wave-top height and opened its throttles, roaring toward the convoy, the men aboard Kimura’s ships were about to learn that the Bismarck Sea had become a trap — and that Japan’s age of naval certainty was ending, one burning ship at a time.

Continue below

Bismarck Sea, March 3, 1943, zero six hundred hours, and Rear Admiral Masatomi Kimura commanding the Lae Resupply Convoy stands on the bridge of his flagship, watching eight destroyers shepherd eight fully loaded transport ships through waters that Japanese naval doctrine says belong to the Empire.

The convoy carries the 51st Division’s desperately needed reinforcements, 6,900 soldiers who’ve been promised to Lieutenant General Hatazō Adachi at Lae, and Kimura has every reason to believe they’ll arrive safely because Japanese warships have sailed these waters for more than a year without serious challenge from American surface forces. What Admiral Kimura cannot possibly know, what no Japanese naval officer could imagine in their darkest nightmares, is that American mechanics in Australian workshops have transformed medium bombers into something that will make these waters a killing field, and within four hours, modified B-25 Mitchell bombers with eight fifty-caliber machine guns protruding from their noses like the fangs of some mechanical demon will turn his convoy into burning wreckage scattered across the Bismarck Sea.

The Japanese Navy’s confidence comes from experience, from victories at Pearl Harbor and the Java Sea, from the seeming inability of high-altitude American bombers to hit moving ships, and from the belief that their destroyers’ anti-aircraft guns can handle any low-flying aircraft foolish enough to approach within range. Captain Tameichi Hara, commanding the destroyer Shigure, has sailed these waters between Rabaul and Lae multiple times, and he knows the Americans have tried everything to stop Japanese convoys, including high-level bombing from B-17 Flying Fortresses that rarely hit anything, torpedo attacks that require long straight approaches that make the attacking aircraft perfect targets, and medium-altitude bombing that gives ships plenty of time to maneuver away from falling bombs.

The Imperial Japanese Navy has developed specific tactics for dealing with aerial threats, including rapid evasive maneuvers, concentrated anti-aircraft fire from multiple ships, and fighter cover from the 11th Air Fleet based at Rabaul, and these tactics have worked well enough that Admiral Gunichi Mikawa approved this convoy despite knowing the Americans would detect it.

Japanese naval officers understand aerial warfare differently than their American counterparts, viewing it primarily as a battle between ships and horizontal bombers or torpedo planes. Encounters where disciplined anti-aircraft fire and sharp maneuvering can defeat most attacks.

Commander Yasumi Doy aboard the destroyer Tokitic has drilled his gun crews relentlessly, teaching them to concentrate their 25mm cannons on approaching aircraft to lead their targets properly and to maintain steady fire even when under attack. The convoy’s anti-aircraft defenses include more than 125mm guns, dozens of 13mm machine guns, and the 5-in dualpurpose guns of the destroyers, creating what Japanese doctrine calls an umbrella of steel over the ships.

These defenses have proven effective against conventional attacks, shooting down or driving off American bombers on numerous occasions, giving the Japanese confidence that they can handle whatever the allies throw at them. The transport ships themselves carry vital cargo beyond just the soldiers, including ammunition, medical supplies, food, and equipment that the Japanese forces at Lad desperately need to maintain their position in New Guinea.

The largest transport, Kembaru, displaces over 6,000 tons and carries an entire regiment of the 51st Division. Men who’ve been waiting at Rabbal for weeks for weather conditions that would allow the convoy to sail. Each transport has been carefully loaded to maximize the number of troops while still carrying essential supplies, and the soldiers have been briefed that they’re sailing into a combat zone where American aircraft are active, but where Japanese naval superiority should protect them during the relatively short voyage to LA. The convoy maintains a precise formation with destroyers screening the

transports, ready to respond to submarine attacks or aerial threats, following procedures that have been refined through two years of war in the Pacific. What makes March 3rd, 1943 different from every previous convoy operation is not immediately apparent to the Japanese lookouts who spot the first American aircraft approaching from the south.

Lieutenant Commander Aicada aboard the destroyer Asashia reports multiple contacts at medium altitude. What appears to be a standard American bombing formation of B7s and B25s approaching at around 7,000 ft. Exactly the kind of attack the convoy has prepared for. The Japanese gun crews swing their weapons toward the approaching aircraft, calculating deflection and altitude, preparing to throw up the curtain of anti-aircraft fire that has protected so many convoys before.

But they don’t yet see the other aircraft approaching at wavetop height. B25 Mitchells that have been modified in ways the Japanese cannot imagine. The modification of B25 Mitchell bombers into strafer gunships represents one of the most significant tactical innovations of the Pacific War.

Born from frustration with the ineffectiveness of conventional bombing against ships, Major Paul Irvin Gun, known as Papy, a former Navy pilot turned Army Air Force’s officer, understood that hitting moving ships from high altitude was nearly impossible and that torpedo attacks required specialized training and equipment the Army Air Forces didn’t have in the Southwest Pacific.

Working with North American Aviation Field Representative Jack Fox at Eagle Farm Airfield near Brisbane, Australia, Gun began installing additional 50 caliber machine guns in the nose of B25 bombers, removing the bombader position and creating space for four guns initially, then expanding to eight guns in later modifications.

The work required extensive reinforcement of the aircraft’s no structure, additional ammunition storage, and careful weight distribution to keep the aircraft balanced. challenges that Gunn and his mechanics solved through trial and error.

The 50 caliber machine guns chosen for these modifications fired the M8 armor-piercing incendiary round, a 619 grain projectile that traveled at 2,910 ft per second, capable of penetrating the deck armor of destroyers and setting fires with its incendiary component. Each gun could fire 850 rounds per minute. Meaning eight guns firing together unleash 6,800 rounds per minute, a stream of destruction that could literally saw through a ship superstructure, destroy anti-aircraft positions, and kill exposed crew members before they could react. The psychological effect of facing this weapon would prove as devastating as its

physical destruction. As Japanese sailors who survived these attacks would describe the terror of seeing a B-25’s nose light up with muzzle flashes, knowing that hundreds of armor-piercing rounds were about to tear through their ship.

The development of skip bombing tactics complemented the strafer modifications perfectly, allowing B-25s to attack ships at mass height while delivering bombs with deadly accuracy. Major William Ben of the 43rd Bombardment Group had pioneered the technique using B7s, discovering that bombs dropped from 200 to 250 ft above the water would skip like stones, bouncing into the sides of ships or exploding close enough to cause fatal damage.

The technique required precise timing and incredible courage as pilots had to fly straight and level toward their targets at low altitude, making themselves perfect targets for anti-aircraft fire. But the accuracy achieved was revolutionary compared to high altitude bombing, pilots practiced endlessly against the wreck of SS Pruth on a reef near Port Moresby. Learning to judge distances, speeds, and release points until they could consistently skip bombs into targets.

General George Kenny, commanding the fifth air force, recognized the potential of combining guns strafer modifications with skip bombing tactics, creating what he called commerce destroyers that could devastate Japanese shipping. By March 1943, the third attack group had fully converted to strafer configuration with the 90th bombardment squadron commanded by Major Edward Lner leading the way in developing attack tactics that maximized the effectiveness of the eight gun nose.

The standard attack profile called for B-25s to approach at 1,00 to 1,500 ft, then drop to wave top height about 2 mi from the target, accelerating to maximum speed while the pilot aligned his aircraft with the target ship. At 1,500 yards, the pilot would open fire with all eight nose guns, hosing the target with armor-piercing incendiary rounds while maintaining his approach for skip bombing. The first indication Admiral Kimura has that something unprecedented is about to happen comes when the B7s at 7,000 ft begin their bombing runs, drawing the attention of every Japanese anti-aircraft gun in the convoy. The destroyer crews perform exactly as trained, putting up an impressive barrage of 25mm and 5-in fire. Their tracers creating a deadly pattern in the sky around the American bombers.

But this is exactly what the American planners intended. While every Japanese eye watches the high altitude bombers, while every gun barrel points skyward, 13 Royal Australian Air Force bow fighters and 12 B25 Mitchell Strafers of the third attack group come in at wavetop height from the southwest, approaching so low that their propeller wash creates spray patterns on the ocean surface. Major Edward Lner leads the B-25 attack in his Mitchell, nicknamed Ruthless.

And as he approaches the destroyer Shiryuki at 280 mph, he can see Japanese sailors on deck pointing at his aircraft in shock and confusion. The Japanese have seen B25s before, but never configured like this. Never with eight black holes in the nose where machine guns protrude like accusatory fingers. Never approaching at an altitude where the pilot can see individual faces on the ship’s deck.

Lner waits until he’s 1,200 yd from Shiryuki before squeezing his trigger. and instantly eight streams of 50 caliber death reach out toward the Japanese destroyer. The tracer rounds creating solid lines of light between aircraft and ship. The effect on Shiryuki is instantaneous and catastrophic as hundreds of armor-piercing incendiary rounds slam into her bridge and superructure at 2,910 ft per second.

The bridge windows explode in showers of glass that shred anyone standing nearby. The thin armor of the gun shields provides no protection against 50 caliber rounds that punch through steel like paper. And within seconds, the destroyer’s anti-aircraft guns fall silent as their crews are literally torn apart by the concentrated fire.

A Japanese Nsign named Takashi Mietta, one of the few survivors from Shiryuki’s bridge, would later describe the attack as like being caught in a giant metal cutting saw. Watching his captain and most of the bridge crew cut down in seconds by rounds that sparked and flashed as they tore through steel bulkheads.

Lner maintains his firing run for eight seconds, pouring over 900 rounds into Shiryuki before releasing two 500lb bombs that skip across the water like stones, slamming into the destroyer’s hull just below the waterline. The bombs fitted with 5-second delay fuses penetrate Shiryuki’s hull before detonating. The explosions breaking the destroyer’s back and opening massive holes that flood her engine rooms within minutes.

As Lner pulls up and away, his gunner spraying the destroyer’s deck with his turret-mounted 50 calibers. Shiryuki is already listing heavily to port. Her crew abandoning their guns to fight flooding that cannot be controlled. Behind Lner, 11 more B25s are selecting targets among the convoy.

Their pilots amazed at how the Japanese ships seem paralyzed by this unprecedented form of attack. Lieutenant John Henibri in the hag targets the transport Kaakusi Maru, walking his eight gun burst from bow to stern, watching his tracers punch through the ship’s bridge, demolish her forward cargo handling equipment, and silence her anti-aircraft positions before his skip bombs tear into her hull.

The transports captain trying to maneuver away from the attack finds his helm not responding because the helmsman and most of the bridge crew are dead. Cut down by 50 caliber rounds that turned the bridge into a charal house of shattered bodies and twisted metal.

The bow fighters add to the carnage their four 20mm cannons and six 303 caliber machine guns focusing on anti-aircraft positions and bridge crews suppressing any attempt at organized defense. Flight Sergeant Fred Cassidy, flying a bow fighter of number 30 squadron, makes his approach toward the transport Tio Maru at 500 ft, diving to mast height in the final seconds while his cannons tear into the ship’s superructure.

Cassidy would later describe watching the ship’s bridge kind of disintegrate under the impact of 20 mm explosive rounds, seeing Japanese sailors thrown into the air by explosions, watching lifeboats shatter into kindling as his rounds found them. The skip bombing proves devastatingly effective as bomb after bomb bounces across the water to slam into Japanese hulls at the water line. The delayed action fuses ensuring the bombs penetrate before exploding.

The transport Noima takes three skip bomb hits in rapid succession. The explosions opening her hull like it can opener, flooding her holds where hundreds of soldiers are packed into spaces meant for cargo. The soldiers wearing full combat gear have no chance of escaping the rapidly flooding compartments.

And witnesses describe hearing their screams even over the roar of aircraft engines and exploding ammunition. Commander Yasumi Doy aboard Tokitake’s watches in horror as his carefully trained gun crews are swept away by streams of 50 caliber fire. Their bodies literally torn apart by the large caliber rounds. He tries to organize a defense, shouting orders to redirect fire toward the low-flying attackers, but his gunners are being killed faster than they can respond, and those who survive are too terrified to stand at their posts as B25s approach with their noses flickering with muzzle flashes. The Japanese Navy has never trained for

this, never imagined that medium bombers could be turned into flying battleships bristling with forward firing guns, never developed tactics to counter an attack that combines strafing and bombing at wavetop height. The destroyer Arashio attempts to maneuver between the attacking aircraft and the transports.

Her captain trying to shield the vulnerable cargo ships with his warship, but this heroic gesture only makes her a priority target. Three B25s concentrate their fire on Aratio. Their combined 24 guns pouring over 2,000 rounds per minute into the destroyer, turning her superructure into twisted metal, killing everyone on her bridge, destroying her fire control systems, and leaving her rudder jammed hard to starboard. Out of control, Arashio collides with the transport Nojima.

Both ships lock together as fires spread between them. Their crews unable to separate the vessels or fight the flames effectively. Admiral Kimura, watching from his flagship as his convoy disintegrates around him, tries to comprehend what is happening. But the attack is unlike anything in Japanese naval experience or doctrine.

The Americans are not following any recognized attack pattern, not making torpedo runs that can be avoided, not dropping bombs from altitude that can be dodged, but instead boring in at point blank range with automatic weapons that turn his ships into slaughterhouses.

He orders evasive maneuvers, but the B-25s are too fast and too numerous, seeming to come from every direction at once. Their eight gun noses spitting death at any ship that tries to maintain formation. The transport oya Maru becomes a particular focus of attack when her captain makes the fatal mistake of turning to present her broadside to approaching B-25s, giving them a perfect target.

Lieutenant Donald McCuller in Sleepy Time Gal approaches from the beam, opening fire at 1,500 yd. His eight guns, sending a stream of armor-piercing incendiary rounds into Ogoa Maru’s hull at the waterline. The rounds penetrate the ship side, starting fires in her cargo holds where ammunition and fuel are stored, creating secondary explosions that blow out entire sections of her hull.

McCuller skip bombs finish what his gun started, breaking Oigga Maru in half. The ship sinking so quickly that most of her 1,500 embarked soldiers have no chance to escape. The attack continues for only 15 minutes. But in that brief time, the carefully organized convoy becomes a scattered collection of burning, sinking wrecks.

The destroyer, Asagumo, trying to rescue survivors from the water, is herself attacked by two B25s whose guns sweep her decks clear of personnel before skip bombs blow holes in her hull below the water line. Japanese sailors in the water, thinking themselves safe from further attack, watch in terror as B25s make strafing runs on lifeboats and swimmers. The American pilots following orders to prevent any Japanese reinforcements from reaching New Guinea.

By 10:15 a.m., as the last B25 disappears toward the south, Admiral Kimura surveys the devastation around him and realizes that the Imperial Japanese Navy has just experienced something that will fundamentally change naval warfare in the Pacific. Of his eight transports, all are sinking or sunk.

Burning funeral pers marking their positions as they slip beneath the waves, taking with them the supplies and equipment desperately needed at La. Four of his eight destroyers are gone, including his flagship Shuryuki, and the surviving destroyers are damaged to varying degrees, their decks covered with dead and wounded, their superructures riddled with 50 caliber holes.

The human cost becomes apparent as the surviving destroyers attempt rescue operations. finding the water filled with bodies and debris, but relatively few living soldiers. Of the 6,900 troops who sailed from Rebel, fewer than 1,200 will eventually reach Lee. Most of these rescued by Japanese submarines that arrive after dark. The majority of the 51st division has been destroyed not in ground combat where they could fight back, not by naval gunfire where they might have had warning, but by modified bombers that turned their transports into death traps in minutes. Captain Tamichihara, one of

the few senior officers to survive, would later write that the attack was like nothing we had ever experienced or imagined possible, describing how the B-25s seemed to saw our ships in half with their concentrated firepower.

The psychological impact on the Imperial Japanese Navy proves even greater than the physical losses. As news of the convoy’s destruction spreads through the fleet, naval officers who had dismissed American bombing as ineffective are forced to confront the reality that the Americans have developed a weapon against which traditional naval defenses are useless.

The 850 caliber guns in each B25’s nose represent more forward-firing automatic weapons than most destroyers carry. And unlike shipmounted guns, these weapons can be brought to bear with the speed and flexibility of aircraft. Japanese naval doctrine based on surface engagements and traditional aerial attacks has no answer for flying gunships that can destroy a convoy in minutes.

Admiral Isuroku Yamamoto, commander and chief of the combined fleet, receives the report of the Bismar sea disaster with visible shock. Understanding immediately that Japan can no longer risk surface vessels in waters within range of American aircraft, the Navy’s inability to protect even a heavily escorted convoy means that reinforcement and resupply of forward positions will become almost impossible, effectively dooming Japanese garrisons throughout the Solomon Islands and New Guinea. Yamamoto orders an immediate review of convoy procedures and anti-aircraft defenses, but

privately admits to his staff that there may be no effective counter to the American Strafer bombers. The transformation of the B25 Mitchell from a conventional medium bomber into a strafer gunship represents American mechanical ingenuity at its finest.

born from the practical needs of warfare rather than pre-war doctrine or planning. Happy gun working with limited resources in primitive conditions created a weapon that would prove more effective against shipping than purpose-built attack aircraft, demonstrating the American talent for innovation and adaptation.

The 8 gun nose modification would become standard on late production B25J models with North American aviation incorporating guns field modifications into factory production creating aircraft that could carry up to 18 forward-firing 50 caliber machine guns. Following the Bismar Sea victory, B25 Strafers spread throughout the Southwest Pacific, appearing wherever Japanese shipping tried to operate.

The 345th Bombardment Group known as the Arapaches received B25 Strafers in August 1943 and immediately began hunting Japanese coastal traffic around New Guinea. Their aircraft decorated with distinctive shark mouths that became synonymous with death to Japanese sailors. The 38th Bombardment Group converted to strafers and developed new tactics for attacking harbors and anchorages, including night attacks using radar to locate targets in complete darkness.

By late 1943, Japanese naval officers reported that daylight movement of anything larger than a fishing boat had become suicidal in waters within B-25 range. The impact on Japanese logistics proves catastrophic as the Navy is forced to rely increasingly on submarines and fast destroyers running at night to supply forward garrisons.

These methods can only deliver a fraction of what surface convoys could carry, meaning Japanese forces throughout the Pacific begin to suffer from shortages of food, ammunition, and medical supplies. The garrison at LA, which the March 3rd convoy was meant to reinforce, never receives adequate supplies and is eventually evacuated in September 1943.

The soldiers forced to march through jungle and mountains with massive casualties from starvation and disease. Japanese attempts to counter the B-25 Strafers prove largely ineffective as the aircraft’s speed and firepower make them difficult targets for fighters.

While their lowaltitude attacks negate the effectiveness of heavy anti-aircraft guns, the Japanese develop new tactics, including suicide attacks by fighters attempting to ram B25s. But these desperate measures cannot stop the steady attrition of Japanese shipping. By mid 1944, the Japanese merchant marine has lost over 60% of its tonnage, much of it to be 25 strafers and skip bombing attacks that turned cargo ships and transports into burning wrecks in minutes.

The B-25 Strafers continue their deadly work throughout 1944, expanding their targets to include Japanese airfields, where their eight gun noses prove equally effective at destroying aircraft on the ground. The August 17th, 21, 1943 raids on Wiiwac demonstrate this versatility as B25 strafers destroy over 170 Japanese aircraft in a series of low-level attacks that leave the Japanese Fourth Air Army virtually helpless.

Japanese pilots describe the horror of watching B25s approach at treetop level. Their nose guns destroying everything in their path, turning carefully dispersed aircraft into burning wreckage before bombs complete the destruction. During the battle of Bayak in May June 1944, B-25 Strafers again proved their worth against Japanese naval forces attempting to reinforce the island.

On June 8th, 1944, 10 B25s of the 17th Reconnaissance Squadron attack a Japanese destroyer flotilla. Their eight gun noses riddling the destroyer Harrison with armor-piercing incendiary rounds before skip bombs send her to the bottom. The attack forces the Japanese to abandon their reinforcement effort, leaving the Bayak garrison to fight without support.

Another example of how B25 strafers could influence entire campaigns by denying the enemy freedom of movement at sea. The crews flying these modified B-25s develop their own culture and traditions, painting elaborate nose art on their aircraft, giving them names like Dirty Dora, Pluto, and Hell’s Angel that reflect their aggressive role.

These men understand they’re flying something unique in warfare. An aircraft that combines the range and payload of a bomber with firepower exceeding that of most fighter aircraft. They take pride in their ability to destroy shipping that conventional bombers cannot hit.

Knowing that every Japanese vessel they sink means fewer supplies and reinforcements reaching enemy garrisons. The Japanese soldiers and sailors who survive encounters with B25 strafers carry psychological scars that affect their performance in subsequent operations. Lieutenant Hiroshi Yamamoto, a survivor from the transport Kaikusi Maru, describes recurring nightmares about the American planes with eight eyes of death.

Unable to forget the sight of his shipmates being torn apart by 50 caliber fire, commander Toshio Abe, who witnessed the Bismar Sea massacre from a rescue destroyer, reports that his crew becomes paralyzed with fear whenever they hear aircraft engines, knowing that B25 strafers could appear at any moment. The effectiveness of the B-25 Strafer forc’s fundamental changes in Japanese strategic planning as commanders must now assume that any daylight movement will be detected and attacked.

Operations that would have been routine in 1942 become impossible by late 1943, forcing the Japanese to adopt increasingly desperate measures to maintain their scattered garrisons. The famous Tokyo Express destroyer runs to Guadal Canal represent one adaptation, using speed and darkness to avoid air attack.

But even these high-speed runs suffer losses when B25 Strafers equipped with radar begin hunting at night. By early 1944, Japanese naval officers are writing reports describing the B-25 Strafer as the most feared weapon in the Pacific. More devastating than submarines, more accurate than dive bombers, more flexible than torpedo planes.

Vice Admiral Shagaru Fucadome, chief of staff of the combined fleet, admits in a classified report that the Imperial Navy has no effective defense against mass strafer attacks, recommending that surface vessels avoid operating within 500 m of American air bases.

This essentially concedes vast areas of the Pacific to American control as B-25s operating from forward bases can cover enormous areas of ocean. The Australian contribution to the B-25 Strafer Force deserves special recognition as Royal Australian Air Force crews fly alongside Americans throughout the campaign. Number 18 squadron RAAF operates B25 Strafers from 1944 onward.

Their aircraft distinguished by RAF roundles but carrying the same devastating eight gun nose configuration. Australian pilots prove particularly aggressive in attacking Japanese coastal shipping around the Netherlands East Indies. Their intimate knowledge of regional waters allowing them to find targets that American crews might miss. The technical evolution of the B-25 Strafer continues throughout the war with later modifications including rocket launchers, improved gun sights, and even experiments with 75mm cannons for attacking larger vessels.

The B-25J22, the ultimate strafer variant, carries eight nose guns for package guns on the fuselage sides, two in the top turret, two in waist positions, and two in the tail. A total of 1850 caliber machine guns that can deliver devastating firepower from multiple angles.

These late war variants are flying arsenals capable of destroying entire convoys single-handedly. German and Italian military observers when they learn about American strafer tactics through intelligence reports express amazement at the concept of converting medium bombers into gunships. The Luftwaffer attempts similar modifications with Junker’s J88 aircraft, installing forward firing cannons for anti-shipping attacks, but never achieves the concentrated firepower of the B-25’s eight gun nose.

Italian forces in the Mediterranean use similar skip bombing techniques with their SM79 torpedo bombers, but lack the forward firepower to suppress anti-aircraft defenses the way B-25 Strafers can. The impact of the B-25 Strafer extends beyond its immediate tactical success, influencing postwar aircraft design and military doctrine.

The concept of a heavily armed gunship proves so successful that it leads directly to the development of aircraft like the AC-47 Spooky and AC-130 Spectre gunships used in Vietnam and subsequent conflicts. The integration of massive forward firepower in an aircraft designed for other purposes becomes a standard American military practice traced directly back to papy guns modifications in Australia. Japanese military historians writing after the war acknowledged that the B-25 strafer represents one of the most significant tactical innovations of the Pacific War comparable to radar or codereing in its impact. Professor

Masanori of the Japanese Defense University writes that the Strafer bomber destroyed not just our ships but our entire concept of naval warfare forcing Japan to abandon offensive operations earlier than would otherwise have been necessary.

The inability to protect shipping from strafer attack accelerated Japan’s defeat by preventing the concentration of forces for counteroffensives. The stories of individual B25 strafer attacks become legendary within the units that fly them passed down from veteran crews to replacements as examples of what the aircraft can accomplish. The attack on Simpson Harbor at Rebal on November 2nd, 1943.

C7B25 strafers sweep across the anchorage at mast height. their guns destroying or damaging dozens of vessels while skip bombs sink larger ships at their moorings. Japanese witnesses described the harbor being turned into a cauldron of burning oil and exploding ammunition in less than 10 minutes with rescue efforts impossible due to continued strafing of anyone who ventures onto the docks.

The modification process itself becomes increasingly sophisticated as mechanics gain experience with the B-25 structure and capabilities. By late 1943, field modification centers can convert a standard B25 to strafer configuration in less than a week, installing the eight-nose guns, additional ammunition storage, and reinforced mounting points with practiced efficiency. The ammunition feed systems are refined to prevent jamming during violent maneuvers.

Gun harmonization is perfected to concentrate fire at optimal range and trigger mechanisms are modified to allow the pilot to fire selective guns or all eight simultaneously. The skip bombing technique also evolves as pilots gain experience attacking different types of vessels under varying conditions.

Pilots learn that approaching at a slight angle rather than directly beam on makes it harder for anti-aircraft gunners to track them while still allowing accurate bomb delivery. They discover that releasing bombs at exactly 60 ft altitude and 340 yard from the target produces optimal skip patterns with the bombs bouncing once or twice before striking at the water line.

The delay fuses are adjusted based on target type with 4-second delays for thin skin transports and 6-second delays for armored warships. The Japanese Navy’s attempts to adapt to the strafer threat include desperate measures such as mounting additional light anti-aircraft guns on every available space.

But these additions prove inadequate against the volume of fire from eight synchronized 50 caliber machine guns. Some Japanese captains try radical evasive maneuvers, including stopping dead in the water or reversing course suddenly. But the B-25 speed and maneuverability allow pilots to adjust their aim quickly.

The installation of radar-directed anti-aircraft guns on some Japanese vessels provides marginal improvement. But by the time these systems are deployed, American superiority in the air is so complete that most attacks involve overwhelming numbers. The maintenance crews supporting B-25 Strafer operations deserve recognition for keeping these heavily modified aircraft operational under primitive conditions.

The 8-nose guns require constant maintenance to prevent corrosion in the humid Pacific environment. Ammunition feeds must be cleaned and adjusted after every mission, and the stress of low-level operations causes increased wear on engines and airframes. Crew chiefs work through tropical nights to prepare aircraft for dawn missions.

Knowing that mechanical failure during a low-level attack almost certainly means death for the air crew. The intelligence network supporting strafer operations proves equally important with coast watchers, submarine patrols, and code breaking providing information about Japanese ship movements. B-25 squadrons often receive targeting information just hours before a mission, allowing them to catch Japanese vessels at their most vulnerable moments.

The ability to strike targets of opportunity, made possible by the B-25’s range and firepower, means that no Japanese vessel can consider itself safe anywhere within 500 m of an American airfield. The human cost of strafer operations on American crews cannot be ignored as low-level attacks against defended targets result in significant casualties.

The third attack group alone loses over 40 B-25s during the war. Most shot down during strafing attacks when they’re most vulnerable to ground fire. The psychological stress of flying directly at enemy guns. Maintaining steady flight while under fire and pulling up at the last second to avoid collision takes its toll on pilots and crews.

Many veteran pilots develop nervous conditions that force them to be relieved from combat duty. Their limits reached after too many missions watching tracer rounds reaching for their aircraft. The B-25 Strafer success influences American tactical doctrine throughout the military, demonstrating that innovative field modifications can sometimes prove more effective than purpose-built weapons.

The willingness of commanders like General Kenny to support unconventional solutions, even when they violate established doctrine, proves crucial to American success in the Pacific. The Strafer program shows that giving creative individuals like Papy Gun the resources and freedom to experiment can produce revolutionary results that change the entire nature of warfare.

Japanese survivors of Strafer attacks often express a particular horror at the impersonal nature of the weapon, describing how the eight gun nose turns killing into an industrial process. Unlike dive bombing or torpedo attacks where individual skill matters greatly, the B-25 Strafer simply points its nose at a target and unleashes a stream of destruction that eliminates everything in its path.

One Japanese officer compares it to being attacked by a flying machine gun nest. Impossible to suppress, impossible to escape, arriving without warning to turn ships into charalous houses in seconds. The final evolution of B-25 strafer tactics comes in 1945 as crews prepare for the invasion of Japan, developing techniques for attacking suicide boats, coastal defenses, and industrial targets.

The eight gun nose proves equally effective against land targets, turning railroad locomotives into scrap metal, destroying radar installations, and suppressing anti-aircraft positions during larger raids. Plans exist for massive strafer sweeps across Japanese harbors and anchorages intended to destroy the remnants of the Imperial Navy before invasion forces arrive.

Though Japan’s surrender makes these operations unnecessary, the legacy of the B25 Strafer lives on in modern military aviation where the concept of heavily armed ground attack aircraft remains central to tactical doctrine. The A10 Thunderbolt 2 Warthog with its massive 30mm cannon represents a direct descendant of the B-25 Strafer designed to destroy ground targets with overwhelming firepower delivered at close range.

The success of gunship aircraft in conflicts from Vietnam to Afghanistan can be traced directly back to the workshops in Australia where Papy Gun first installed eight machine guns in a bombers’s nose. Veterans of B25 Strafer units hold reunions decades after the war. sharing memories of missions that seemed suicidal at the time but proved devastatingly effective.

They remember the smell of cordite filling the cockpit as eight guns fired simultaneously. The vibration that shook the entire aircraft, the sight of Japanese ships coming apart under their fire. These men know they flew something unique in the history of aerial warfare.

An improvised weapon that proved more effective than anything designers had planned. A testament to American ingenuity and adaptability. The Japanese military in postwar analyses identifies the B-25 Strafer as one of three innovations that doomed their empire alongside radar and codereing. The inability to protect shipping from strafer attack meant that Japan’s island empire could not be sustained as garrisons withered from lack of supplies while reinforcements never arrived.

Admiral Somu Toyota, the last commander and chief of the combined fleet, states simply that the 8 gun B25 destroyed our ability to move by sea. a capability that Japan as an island nation could not afford to lose. The technical specifications of the B-25 Strafer become legendary among aviation enthusiasts who marvel at the audacity of installing 850 caliber machine guns in an aircraft never designed for such arament.

Each gun weighs 64 lb, fires 850 rounds per minute, and requires elaborate ammunition feed systems to maintain continuous fire. The eight guns together weigh over 500 lb, not counting ammunition, requiring careful weight distribution to maintain the aircraft’s center of gravity.

The ammunition load of 400 rounds per gun means 3,200 rounds total, enough for approximately 30 seconds of continuous fire, though pilots rarely fire for more than 8 seconds at a time. The B-25 Strafer represents more than just a successful weapon system. It embodies the American approach to warfare in World War II, combining technological innovation, tactical flexibility, and aggressive execution.

Where other nations might have spent years developing a purpose-built Strafer aircraft, Americans modified existing bombers in field workshops, tested them in combat, and refined them based on experience. The willingness to experiment, to accept risk, and to trust the judgment of combat personnel over distant planners proved crucial to victory in the Pacific.

As the war ends, B-25 Strafer crews are among the most decorated in the Army Air Forces. Their missions having directly contributed to the isolation and defeat of Japanese forces throughout the Pacific. The presidential unit citations, distinguished flying crosses, and silver stars earned by Strafer crews reflect the extreme danger and exceptional effectiveness of their operations.

These decorations, however, cannot fully capture the impact of their service. The sight of eight streams of tracer fire reaching out to destroy enemy ships, turning the tide of battle in 15 minutes over the Bismar Sea. The last B-25 Strafer mission of World War II occurs on August 14th, 1945, the day Japan announces its surrender. As aircraft of the 345th Bombardment Group attack Japanese shipping in the inland sea, even at the wars end, with Japan’s defeat certain, the eight gun noses prove their worth, destroying several small vessels attempting to flee to Korea. The crews returned to find the war over. Their unique weapon no longer needed, though the concept they proved

would influence military aviation for generations to come. In the final analysis, the B-25 Strafer stands as perhaps the most successful field modification in military aviation history, transforming a conventional medium bomber into a shipkilling monster that terrorized Japanese naval forces.

From Papy Gun’s first experiments at Eagle Farm to the mass-produced B25J22 with 18 guns, the Strafer program demonstrates how innovation born from necessity can exceed anything planned by conventional wisdom. The 850 caliber guns protruding from the B-25’s nose became a symbol of American determination and ingenuity, proving that in modern warfare, the side that adapts fastest often wins.

The story of Japan’s encounter with the B-25 Strafer is ultimately one of technological surprise and tactical revolution where assumptions about aerial warfare were shattered in minutes over the Bismar Sea. The Imperial Japanese Navy, proud inheritor of samurai tradition and victor at Tsushima found itself helpless against mechanics from Texas and pilots from Kansas who turned bombers into flying buss.

The eight gun nose that Admiral Kimura saw approaching his convoy on March 3rd, 1943 represented not just a new weapon, but a new kind of warfare. One where innovation trumped tradition and where a few modified aircraft could destroy an empire’s ability to sustain itself.

News

CH2 Japanese Admirals Never Knew Iowa’s 16 Inch Guns Could Hit From 23 Miles- Until They Had To Learn The Lesson Paid With 4 Of Their Ships

Japanese Admirals Never Knew Iowa’s 16 Inch Guns Could Hit From 23 Miles- Until They Had To Learn The Lesson…

CH2 What Eisenhower Told Staff When Patton Turned His Army 90 Degrees in 48 Hours Shocked The Entire Meeting

What Eisenhower Told Staff When Patton Turned His Army 90 Degrees in 48 Hours Shocked The Entire Meeting In…

CH2 How One Mechanic’s “Illegal” Engine Trick Made Mosquito Bombers Outrun Every German Fighter

How One Mechanic’s “Illegal” Engine Trick Made Mosquito Bombers Outrun Every German Fighter The De Havilland Mosquito shouldn’t have worked….

CH2 When a 72-Hour Retreat Turned Into a 300-Mile Counterattack That Germany Never Believed Possible

When a 72-Hour Retreat Turned Into a 300-Mile Counterattack That Germany Never Believed Possible At dawn on February 20th, 1943,…

CH2 The Army Tried to Kick Him Out 8 Times — Until He Defeated 700 German Troops with Just 35 Men

The Army Tried to Kick Him Out 8 Times — Until He Defeated 700 German Troops with Just 35 Men…

CH2 How One Farmhand’s “STUPID” Rope Trick Destroyed 35 Zeros in Just 3 Weeks

How One Farmhand’s “STUPID” Rope Trick Destroyed 35 Zeros in Just 3 Weeks May 7th, 1943. Dawn light seeped…

End of content

No more pages to load