Japan Built “Impregnable” Fortresses With 110,000 Troops. The US Just Did Something That Made All Of Them Shocked

At 8:37 in the morning on February 17th, 1944, the first wave of Hellcat fighters roared off the deck of the aircraft carrier Enterprise, slicing through the pre-dawn gloom over Truk Lagoon. Vice Admiral Raymond Spruance stood rigid on the bridge of his flagship, eyes scanning the horizon through binoculars, his mind balancing between tactical calculation and the raw tension that accompanied every carrier strike. Nine carrier task groups, their decks bristling with aircraft, steaming in precise formation, were poised to execute Operation Hailstone. The stakes were monumental.

Truk had earned the moniker “the Gibraltar of the Pacific,” and with good reason. The Japanese high command had poured decades of resources, manpower, and ingenuity into transforming a cluster of coral atolls into a fortress. Within the barrier reef, which stretched forty meters across at its widest, lay between ten and twelve thousand soldiers, sailors, and airmen. Five airfields punctuated the islands, each crammed with hundreds of aircraft hidden in hardened revetments. Coastal defense guns dominated every approach, their muzzles capable of sending shells into the surrounding lagoon with lethal precision. Underground bunkers carved from volcanic rock could shelter the entire garrison, designed to withstand bombardments that would have demolished less meticulously fortified positions. Fuel depots, both aviation and bunker oil, were carefully stockpiled, alongside ammunition magazines sufficient to sustain prolonged combat. The Japanese had devoted twenty years of meticulous planning to making Truk invulnerable, a hub from which the combined fleet could project power across the Central Pacific.

American military planners had studied Truk exhaustively. Filing cabinets groaned under the weight of maps, intelligence reports, and tactical analyses. Beach landing zones were mapped in painstaking detail; naval gunfire support coordinates were charted with centimeter-like precision; casualty evacuation plans were drawn in layers of contingency. Every projection came to the same unflinching conclusion: a direct assault would be catastrophic. An amphibious invasion would demand multiple Marine divisions, weeks of preliminary bombardment, and house-to-house fighting through every fortified bunker, pillbox, and slit trench. Casualties would be enormous, dwarfing the losses at Tarawa, which had already seared itself into the collective memory of the American public and military leadership alike.

But the carriers steaming toward Truk were not preparing for an invasion. Spruance’s strategy was daring, almost audacious, and one that the Japanese high command had not anticipated. The Americans had decided to neutralize Truk without capturing it, to render its fortress irrelevant, and to do so in a manner that would preserve American lives while dealing a crippling blow to the Japanese forward base. Traditional military doctrine for island warfare was simple and brutally linear: identify the enemy stronghold, assemble overwhelming force, bombard it relentlessly from sea and air, then send thousands of men to storm the beaches and fight for every meter of ground until victory was secured. The Marine Corps had executed this doctrine repeatedly—Guadalcanal, Tarawa, Makin, and dozens of other Pacific islands. It worked, but at a human cost that was staggering.

The problem had never been American courage or training. It was mathematics. Attacking a heavily fortified position head-on gave the defender overwhelming advantage. The Japanese knew exactly where amphibious landings would occur. They had months or even years to prepare. Bunker systems were interconnected, fields of fire overlapped, artillery emplacements pre-targeted beaches, mines were hidden under surf and sand, and tunnels allowed troops to move unseen and strike without warning. Ammunition and provisions were stockpiled for sieges, giving defenders the ability to outlast any conventional assault. To overcome such fortifications, attacking forces needed numerical superiority of at least three to one, and even that was no guarantee of success. Tarawa had demonstrated this brutal reality.

In November 1943, American forces assaulted Betio Island in the Gilberts as part of Operation Galvanic. The island was tiny, only 290 acres—roughly the size of the National Mall—but its defenders were formidable. Four thousand five hundred Japanese troops, expertly positioned and supplied, faced off against 18,000 Marines supported by naval gunfire, air strikes, and the newest amphibious vehicles. Detailed intelligence, rigorous planning, and exhaustive rehearsal had been intended to tilt the odds in America’s favor.

At dawn on November 20th, naval bombardment commenced. Ships pounded Betio’s bunkers and defensive positions for hours, while carrier aircraft strafed and bombed at low altitude, meant to destroy defensive positions and stun the defenders. Yet, for all the firepower, the effect was limited. When the first wave of Marines landed in amphibious tractors, many were stranded on the coral reef by the low tide, exposed to withering fire. Japanese defenders, well dug in, emerged from bunkers and slit trenches with pre-aimed machine guns, rifles, and artillery, creating a firestorm that tore through the landing forces with surgical precision. The Marines expected resistance; they did not anticipate devastation on such a scale.

Soldiers waded through chest-deep water, bullets slamming into their flak jackets, tearing through unprotected limbs, the screams of the wounded and dying mingling with the roar of guns and explosions. The coral reef, once seen as an obstacle for landing craft, had become a killing field, stranding men helplessly under intense fire. Those who reached the beach found themselves pinned under interlocking fields of fire from concrete bunkers. Every approach had been pre-targeted by Japanese defenders. The Marines advanced meter by meter, using flamethrowers, satchel charges, and bayonets to reduce bunkers one at a time. Fighting stretched into the night, hand-to-hand combat breaking out amidst the smoke, blood, and chaos. By the third day, the Americans held the island only through extraordinary perseverance and staggering sacrifice.

Tarawa’s lessons weighed heavily on the minds of every naval and Marine Corps officer tasked with planning the next operation. Truk was bigger, better defended, and even more daunting. One hundred and ten thousand Japanese personnel occupied the atoll complex. Artillery, aircraft, mines, and fortified positions made a direct assault not just costly but potentially catastrophic. Casualty projections for a frontal assault were chilling. Even with overwhelming naval gunfire and air support, any amphibious landing would still expose troops to precise, lethal fire from positions that had been optimized for defense over decades.

Yet the United States had learned something crucial: sometimes, overwhelming force was not the only way to achieve objectives. Operation Hailstone embodied a strategic evolution. Rather than fighting for every bunker, pier, and revetment, American commanders focused on neutralization—destruction of aircraft on the ground, sinking of shipping, elimination of fuel supplies—followed by bypassing the fortified islands entirely. The goal was not occupation; it was paralysis. If Truk’s fleet, air force, and logistics could be destroyed without a costly beach landing, the island could no longer serve as a strategic hub, rendering all the planning and fortifications irrelevant.

From the deck of the Enterprise, Spruance watched as the first Hellcats disappeared over the horizon, their silhouettes sharp against the rising sun. Bombers, torpedo planes, and dive-bombers followed in carefully timed waves. Naval gunners adjusted for wind, distance, and range. Coordination was flawless, a product of meticulous training and months of preparation. In less than an hour, the sky over Truk would erupt in a ferocious assault the Japanese had not anticipated, a methodical destruction that left their formidable defenses bypassed without ever risking thousands of American lives in a prolonged siege.

Spruance’s mind raced through calculations, predictions, and contingencies. He knew the danger was real. Even neutralization carried risks; Japanese aircraft might rise to intercept, coastal guns could find targets, anti-aircraft fire would pepper the sky. Yet the calculus favored the attackers. The fortress of Truk, once considered impregnable, now faced a form of warfare it had never been designed to withstand: rapid, concentrated aerial assault aimed not at conquest, but at annihilation of its operational capability.

On the islands themselves, Japanese commanders remained unaware of the scale of the impending assault. Years of confidence, drilled into them through doctrine and preparation, left them certain that Truk could withstand anything short of a full-scale invasion. The men in bunkers, tunnels, and revetments went about their routines, unaware that their positions, their intricate preparations, and their very sense of security would be challenged in ways no chart, map, or plan could have foreseen.

As the first bombs fell and tracers cut the morning light, the American attack began to unfold with devastating precision. Spruance watched quietly, noting the coordination of waves, the effectiveness of targeting, the speed with which defenders were overwhelmed by simultaneous threats from multiple directions. The fortress, though still standing in its entirety, was already being rendered irrelevant. In minutes, the carefully honed Japanese defenses would prove inadequate against a strategy that sought to neutralize rather than capture.

Operation Hailstone was about to demonstrate a new form of warfare in the Pacific—one that valued speed, precision, and strategic intelligence over brute force and massed infantry assaults. It would shock the Japanese high command, forcing a reevaluation of doctrines long thought inviolable. For now, however, the carriers steamed steadily, the air was filled with the roar of engines, and the sun climbed higher over Truk Lagoon, illuminating a fortress whose legendary reputation was about to be tested in a manner its designers had never imagined.

The question lingered in every mind aboard the Enterprise and every cockpit in the strike waves: could one of the Pacific’s most fortified positions, armed with decades of preparation and over a hundred thousand troops, truly be neutralized without the kind of human cost that had defined Tarawa? Spruance, focused and calculating, allowed himself only a moment of satisfaction. The answer would reveal itself in the hours to come—but for now, the stage had been set, and history was about to witness a shock that would leave the Japanese defenders stunned.

Continue below

At 8:37 in the morning on February 17th, 1944, the first wave of Hellcat fighters launched from the aircraft carrier Enterprise into the pre-dawn darkness over Troo Lagoon. Vice Admiral Raymond Spruent commanding the United States fifth fleet watched from his flagship as nine carrier task groups prepared to execute Operation Hailstone. The stakes were immense.

Truk was the Gibralar of the Pacific. The most heavily fortified Japanese position outside the home islands. The barrier reef surrounding Trukatoll stretched 40 m across. Inside that reef sat approximately 10,000 to 12,000 Japanese soldiers, sailors, and airmen. Five airfields dotted the islands. Hundreds of aircraft filled the hardened revetments. Coastal defense guns commanded the approaches.

Underground bunkers carved into volcanic rock could shelter the entire garrison. Fuel depots held vast quantities of aviation, gas, and bunker oil. Ammunition magazines were stocked for extended combat. The Japanese had spent two decades fortifying Truck as the combined fleet’s primary forward base. American military planners had studied assault scenarios.

The plans filled filing cabinets, beach landing zones, naval gunfire support coordinates, casualty evacuation procedures. Every analysis reached the same conclusion. A direct assault on troop would be catastrophic. The amphibious invasion would require multiple marine divisions, weeks of preliminary bombardment, and house-to-house fighting through fortified positions.

Casualties would dwarf those suffered at Tarowa. But the carriers steaming toward Trroo were not preparing for an invasion. They were executing a strategy the Japanese high command had not anticipated. A strategy that would make the Gibraltar fortress completely irrelevant. The Americans were not going to capture Tru.

They were going to neutralize it and bypass it entirely. The traditional military doctrine for island warfare was simple and brutal. Identify the enemy stronghold. assemble overwhelming force, bombard it from sea and air, then send thousands of men to storm the beaches and fight for every meter of ground until the enemy is destroyed. The United States Marine Corps had executed this doctrine at Guadal Canal, Tarowa, and across dozens of Pacific islands.

It worked, but it killed Americans in devastating numbers. The problem was not American courage or training. The problem was mathematics. When attacking a heavily fortified position head-on, the defender held every advantage. The Japanese knew where landings would occur. They had months or years to prepare. They built interconnected bunker systems with overlapping fields of fire. They positioned artillery to target the beaches. They planted mines.

They dug tunnels, allowing troops to move unseen. They stockpiled ammunition and food for extended sieges. An attacking force needed numerical superiority of at least 3 to one just to have a chance against well-prepared defenders. Even 10:1 was not guaranteed success. The Battle of Tarawa proved this brutally.

In November 1943, American forces assaulted the tiny island of Betio in the Gilbert Islands as part of Operation Galvanic. The island measured 290 acres, roughly the size of the National Mall in Washington. The Japanese had 4,500 defenders, well supplied and expertly positioned. The Americans attacked with 18,000 Marines supported by overwhelming naval and air power. They had new amphibious vehicles.

They had detailed intelligence. They had the finest assault training the Marine Corps could provide. The assault began before dawn on November 20th. Naval bombardment pounded the island for hours. Carrier aircraft strafed Japanese positions. The bombardment was supposed to destroy the defenses and stun the defenders. It did neither.

When the first wave of Marines approached the beaches in their amphibious tractors, Japanese defenders emerged from underground bunkers and opened fire. The Marines had expected light resistance. They encountered a firestorm. Low tides stranded many landing craft on the coral reef surrounding the island.

Marines had to wade hundreds of yards through chestde water under intense fire. Japanese machine guns swept the water. Artillery fire bracketed the wading men. Marines fell by the dozens, their bodies sinking beneath the waves or floating in the lagoon.

Those who reached the beach found themselves pinned down by interlocking fields of fire from concrete bunkers. Japanese defenders had pre-targeted every approach. They had established kill zones covering the entire shoreline. The fighting devolved into brutal close quarters combat. Marines used flamethrowers and satchel charges to reduce bunkers one at a time.

They crawled forward meter by meter under fire. They fought through the night, exhausted and running low on ammunition. Japanese counterattacks during the hours of darkness drove into American positions. Hand-to-hand fighting occurred in the darkness. The Marines held barely. By the third day, superior American numbers and firepower began to tell. Japanese positions were systematically destroyed.

Remaining defenders launched suicidal banzai charges rather than surrender. When the battle ended on November 23rd, American Marines had lost over 1,000 men killed and over 2,200 wounded in 76 hours of fighting. The Japanese garrison had been almost completely annihilated. Only 17 Japanese soldiers and 129 Korean laborers surrendered out of a garrison of 4700. The casualty ratio shocked military planners.

The Marines had outnumbered the defenders 4 to1. They had complete naval and air superiority. They had the advantage in firepower, logistics, and reinforcements. Yet, they still suffered over 3,000 casualties, taking a tiny coral atole. If that ratio held for larger islands with bigger garrisons, the cost of reaching Japan would be astronomical.

Tarawa demonstrated conclusively that frontal assaults on fortified islands, even with overwhelming force, resulted in casualties that the American public might not accept indefinitely. When news of Tarawa’s casualties reached the American public, outrage erupted. Families could not understand why so many men died for such a small island so far from Japan.

Newspapers questioned the strategy. Members of Congress demanded explanations. Major General Holland Smith, who commanded the assault, compared the losses to Pickicket’s charge at Gettysburg. Admiral Chester Nimttz, commanderin-chief of the Pacific Fleet, received hundreds of angry letters from families who had lost sons at Tarawa. One mother wrote, accusing him of murdering her son.

The public wanted to know if there was a better way. Military planners knew what lay ahead. Between Terawa and Japan stretched thousands more islands. Many were more heavily fortified than Tarawa. Some, like Tru and Rabal, held garrisons 10 times larger. If every island required a Tarawa style assault, American casualties would be catastrophic. The United States would lose hundreds of thousands of men before reaching the Japanese home islands.

That level of sacrifice might break public support for the war entirely. The most daunting example was Rabol, located on the island of New Britain in the Bismar archipelago. Rabal had been the primary Japanese base in the South Pacific since January 23rd, 1942. The Japanese had poured resources into Rabal for 2 years.

They built five major airfields at Lacunai, Vunaano, Rapapo, Tobber, and on nearby New Island. They constructed hundreds of kilometers of tunnels into the volcanic rock. They installed 367 anti-aircraft guns. They positioned 43 coastal defense guns to command the harbor approaches.

They stockpiled weapons, ammunition, and supplies for a garrison that grew to over 110,000 men by mid 1943. 110,000 men. That was more defenders than would later be stationed on Okinawa, more than Iima, more than any other single Japanese position in the Pacific except the home islands themselves. Rabol controlled the sea lanes between the Solomon Islands and New Guinea.

Japanese aircraft flying from Rabal could intercept Allied shipping across thousands of square miles. The base was the lynch pin of Japan’s entire South Pacific defense strategy. Taking Rabbal through direct assault would require the largest amphibious operation in the Pacific War to that point.

Planners estimated it would need at least 10 divisions, months of preliminary bombardment, and sustained close combat that would make Tarowa casualties pale by comparison. The human cost was not theoretical. It was measured in individual lives. Marines who survived Tarowa understood the mathematics intimately. Platoons that landed with 40 men walked off Betto with fewer than 20. The survivors had watched friends die on the reef, on the beaches, in the bunkers.

When veterans of the Second Marine Division learned their unit might be assigned to assault Rabbal next, many wrote letters home telling families not to expect them to survive. They had seen what happened when Marines attacked prepared defenses. Attack enough fortified islands and the odds caught up with you.

Every junior officer who had fought at Tarawa knew the calculus. Every company commander who had lost half his men taking a single Japanese pillbox understood the mathematics. If the strategy did not change, most of them would be dead before the war ended. The question was whether anyone in command had the strategic imagination to change the strategy before it was too late.

In March 1943, General Douglas MacArthur stood in his headquarters in Brisbane, Australia. studying a map of the Pacific. The map showed Japanese positions from the Solomon Islands to the Philippines. Red circles marked major enemy bases. The biggest circle was at Rabal. MacArthur’s staff had been developing plans to assault Rabal directly as part of Operation Cartwheel.

MacArthur read the preliminary casualty estimates and rejected the direct assault approach. Too many casualties, too much time. There had to be another way. MacArthur had spent decades studying military history. He knew that the most successful commanders avoided bloody battles by outmaneuvering opponents. Napoleon had mastered this.

So had Robert E. Lee in his best campaigns. The key was attacking where the enemy was weak, not where they were strong. MacArthur looked at the map again. Rabal was strong, but what if American forces did not attack Rabal? What if they simply went around it? The concept was not entirely new. Commanders had bypassed enemy strong points throughout military history. But in the Pacific, the scale was different.

Islands could not retreat if supply lines were cut. Islands became prisons for their own garrisons. A Japanese soldier trapped on a bypassed island could not fight anywhere else. His weapons, ammunition, and training all became irrelevant if he had no enemy to engage. MacArthur refined the strategy he would call leaprogging.

Admiral William Holsey commanding naval forces in the South Pacific supported the concept immediately. The plan was straightforward. Instead of attacking every Japanese base sequentially, Allied forces would identify which islands were truly necessary for the advance toward Japan, they would seize those islands and build airfields.

Then they would use those airfields to provide air cover for the next leap forward. Japanese bases not on the direct route would be bypassed entirely. Allied aircraft and submarines would cut their supply lines. The garrisons would be isolated, left to what MacArthur called wither on the vine. The advantages were clear.

Fewer American casualties, faster progress toward Japan, more efficient use of limited resources. The psychological impact on the Japanese would be devastating. Instead of fighting defensive battles, their troops would sit in bunkers watching American forces steam past toward the home islands. There would be nothing they could do to stop it. But the strategy had critics among senior American military leaders.

Some officers argued that bypassing Japanese forces was too risky. What if the bypassed garrisons launched counterattacks against thinly held American positions? What if Japanese forces from bypassed bases interdicted American supply lines with submarine or air attacks? What if the strategy failed and left American forces exposed and isolated between powerful enemy strong points? These were not idle concerns.

They were legitimate questions about operational risk. The plan required near total air and naval superiority across vast expanses of ocean. If the Japanese could contest control of the air or sea, bypassed bases could become lethal threats, Japanese aircraft flying from Rabbal or Truk could attack American convoys.

Japanese submarines operating from bypassed bases could sink transports carrying supplies and reinforcements. Japanese naval forces could sorty from fortified harbors and engage weaker American units. The entire strategy depended on the United States maintaining complete dominance in the air and at sea. If that dominance faltered, the bypassed bases would become daggers pointed at American supply lines.

But by mid 1943, American industrial production had shifted the balance of power decisively. New Essexclass aircraft carriers were arriving in the Pacific every month. These fast carriers displaced 27,000 tons and carried up to 90 aircraft each. They were the most powerful warships ever built.

Factory production lines in the United States were delivering them faster than the Navy could train crews to man them. Hundreds of new aircraft rolled off assembly lines every week. The Grumman F6F Hellcat fighter was entering service with capabilities that matched or exceeded the Japanese zero. Thousands of trained pilots graduated from flight schools every month. The Japanese could not match this production.

For every carrier Japan lost, there was no replacement. For every experienced pilot Japan lost, training a replacement took months of fuel the Japanese did not have. The mathematics of attrition favored the United States overwhelmingly. If there was ever a time to try a revolutionary new strategy that depended on air and naval superiority, this was it. The debate at the highest levels of American command was intense.

Admiral Ernest King, chief of naval operations, advocated for a central Pacific drive straight toward Japan through the Marshall, Caroline, and Marana Islands. This approach would rely heavily on carrier task forces and would require taking heavily fortified islands like Tru. General Douglas MacArthur advocated for a southwestern Pacific approach through New Guinea and the Philippines.

This approach would allow more extensive use of land-based air power and would bypass many fortified islands. The compromise reached was to pursue both approaches simultaneously. Admiral Chester Nimitz would command the Central Pacific offensive. General Douglas MacArthur would command the southwestern Pacific offensive.

The two campaigns would support each other, forcing the Japanese to divide their dwindling resources between two threats, but both commanders agreed on one principle. Wherever possible, avoid frontal assaults on heavily fortified positions. Use air power and sea power to neutralize enemy bases, then bypass them. The decision was made at the Quadrant Conference in Quebec from August 17th to 24th, 1943.

Allied leaders reviewed plans for capturing Rabbal. The cost in time, men, and material was deemed unacceptable. The decision was to modify Operation Cartwheel. Instead of the original plan to capture Rabal, Allied forces would encircle it, neutralize it with air power, and leave the garrison isolated.

Military staffs began detailed planning for how to neutralize Rabbal without invading it. The key was establishing allied airfields within range of Rabal, but outside effective range of Japanese aircraft based there. Bugenville Island, 200 m from Rabal was ideal.

If the Allies seized the southern tip of Bugenville and built an airfield, they could launch fighters and bombers that would reach Rabal easily. The Japanese had troops on Buganville, but most were concentrated in the south. An amphibious landing at Empress Augusta Bay on the western coast could succeed with manageable casualties. Once the airfield was operational, Rabbal would be under constant air attack.

The second piece was the Admiral T Islands northwest of Rabal. Seizing those islands would cut Japanese shipping routes from the home islands to their South Pacific bases. Rabbal would be surrounded on three sides by Allied air bases. Japanese ships trying to resupply the base would have to run a gauntlet of American submarines and aircraft. Few would make it. The garrison would slowly starve.

On November 1st, 1943, American Marines landed at Empress Augusta Bay on Bugenville. The landing site had been carefully chosen. Most Japanese forces on Bugganville were concentrated in the southern and northern portions of the island. The western coast at Empress Augusta Bay was lightly defended.

The Third Marine Division established a beach head quickly. Japanese forces counterattacked but were repulsed with heavy losses. The Japanese Imperial Navy attempted to interfere with the landings, but was driven off in a night surface action on November 2nd. Within weeks, American engineers carved an airfield out of the jungle at Cape Tookina.

CBS worked around the clock, bulldozing jungle and laying steel matting for runways. By late November, Allied fighters and bombers based on Bugenville were striking Rabbal daily. The distance from Buganville to Rabal was perfect. American fighters could escort bombers all the way to the target and still have fuel to engage Japanese interceptors.

The Japanese tried to defend with their aircraft, but American fighters shot them down in growing numbers. The United States had achieved a critical advantage in pilot training and aircraft production. For every Japanese pilot lost, there was no replacement. For every American pilot lost, two more arrived from training schools in the United States.

For every Japanese aircraft destroyed, production in Japan struggled to build a replacement. For every American aircraft destroyed, factories in the United States had already built five more. By February 1944, the Japanese had lost air superiority over Rabal entirely. Their aircraft could no longer effectively intercept Allied bombers.

The base was being systematically destroyed from the air, and the 110,000 defenders could do little about it. Japanese anti-aircraft guns fired at every raid, but they could not stop the attacks. Ammunition for the guns was running low. Replacement barrels were not available. Fire control systems were wearing out. The defenders were fighting a losing battle of attrition.

On February 17th, 1944, the same day as the attack on Tru, Allied bombers from Bugenville struck Rabal again. It was becoming routine. Japanese anti-aircraft guns fired. A few allied planes were hit. Most dropped their bombs and returned safely. The Rabal garrison had ammunition to shoot back, but they could not stop the attacks. They were trapped.

Their massive fortress had become their prison. 110,000 Japanese soldiers sat in tunnels and bunkers while the war moved on without them. American forces leapfrogged past Rabal to seize Emirro Island in the Admiral T group on March 20th, 1944. The Admiral T Islands operation was executed with remarkable speed. The first cavalry division landed on Los Negros Island on February 29th.

Initially as a reconnaissance in force, finding the Japanese garrison weaker than expected, they secured the island within days. Manis Island, the largest in the group, fell by March 15th, with Emro secured on March 20th. Rabol was completely encircled. The naval base that had been the heart of Japanese power in the South Pacific, was now isolated and irrelevant.

Simpson Harbor, which had once sheltered major elements of the combined fleet, now held only a few damaged vessels that would never sail again. The five airfields at Rabbal still existed, but they were useless without aircraft.

The underground tunnel systems still protected the garrison from bombing, but they also trapped them in a fortress that had become a tomb. Allied attacks on Rabbal eventually became known as milk runs among air crews. Japanese anti-aircraft fire remained heavy, but grew increasingly inaccurate as gun crews ran short of ammunition and replacement parts.

Japanese fighters rarely challenged the bombers because they had so few aircraft left and no way to replace losses. Young pilots fresh from training flew missions over Rabbal to get their first taste of combat before being sent to more dangerous assignments. Rabbal had become a training ground for Allied aviators. The irony was complete. The base the Japanese had spent years fortifying was now just target practice.

But Rabbal was only the first application of the leaprogging strategy. The real test came at Truck. truck was everything Rabal was, but positioned even more strategically. It was the combined fleet’s primary forward base. It was the only major Japanese airfield within range of the Marshall Islands.

It was the logistical hub supporting every Japanese garrison in the central and south Pacific. American intelligence called it the Gibralar of the Pacific. Japanese officers believed it was the strongest defensive position outside the home islands. American planners studied intelligence reports on troop with growing concern.

The Japanese had approximately 10,000 to 12,000 troops on the atal. They had five complete airfields. They had hundreds of aircraft. The lagoon held dozens of warships and merchant vessels at any given time. Defensive guns could engage ships at extreme range. Underground facilities could shelter much of the garrison from aerial bombardment.

If the Americans tried to take Trrook by storm, casualties would be severe. Multiple divisions would be needed. The preliminary naval bombardment alone would take weeks. The ground fighting would be brutal. American planners had a different idea. What if they did to Trou exactly what they had done to Rabal? What if they did not invade it at all? Tru’s strength was its defenses, but defenses only mattered if someone attacked them.

If American forces simply bypassed truck, all those fortifications became worthless. The question was whether bypassing truck was feasible. The Japanese fleet used truck as a forward operating base. If the combined fleet remained at TR while American forces leaprogged past it, Japanese warships could sorty and attack American supply lines.

But American submarines operating near Tru had been sinking Japanese supply ships with increasing frequency. Long range reconnaissance flights had photographed Tru multiple times. If the Japanese anticipated a major operation against Tru, they would likely withdraw the combined fleet to avoid being trapped. Admiral Chester Nimmitz, commander of Pacific Forces, approved the plan.

The strategy was to attack Troo with overwhelming carrier-based air power. The attack would destroy as many ships and aircraft as possible. Then American forces would seize islands to the east and west of Trou, establishing airfields that could keep Trou continuous air attack.

The combined fleet would be forced to withdraw or be destroyed. Once the fleet was gone, Truck’s garrison would be trapped just like Rabbal. The operation was designated Hailstone. Task Force 58, commanded by Rear Admiral Mark Mitcher, would execute the attack. Mitchell was a pioneer of naval aviation who had commanded the carrier Hornet during the dittle raid on Tokyo. He understood carrier warfare better than almost anyone in the navy.

His task force was the most powerful naval striking force ever assembled to that point in history. The force included five fleet carriers, Enterprise, Yorktown, Essex, Intrepid, and Bunker Hill. four light carriers, Bellowwood, Kat, Mterrey, and Cowpens. Together they carried over 560 aircraft. Six fast battleships provided surface striking power and anti-aircraft protection.

Iowa, New Jersey, Massachusetts, Alabama, South Dakota, and North Carolina. Additionally, 12 submarines were positioned around TR to intercept any Japanese ships attempting to flee. The Japanese had some warning that an attack was imminent. American reconnaissance aircraft had photographed troop multiple times in early February. Japanese radar had detected these flights.

Admiral Minichi Koga commanding the combined fleet made a critical decision. He ordered the withdrawal of major warships from Truk to Palao 500 m to the west. The super battleships Yamato and Mousashi departed. the fleet carriers that remained operational after the Solomon’s campaign departed. Heavy cruisers and destroyers followed.

By the time Task Force 58 struck on February 17th, the most valuable Japanese warships had already escaped, but dozens of transports, cargo ships, tankers, and smaller warships remained. These vessels were critical to Japanese logistics. Without them, supplying the garrisons scattered across the Pacific would become nearly impossible.

When American bombs and torpedoes sent these ships to the bottom, they took with them Japan’s ability to sustain forces across the central Pacific. On February 17th, 1944, the first American aircraft launched from carriers 90 mi from Troo. It was still dark. The Japanese had no air patrols active. Their radar could not detect low-flying aircraft. The Americans achieved complete surprise.

The first wave of Hellcat fighters swept over trucks airfields just before dawn. Japanese pilots were scrambling toward their aircraft when American machine guns tore into them. Planes exploded on the runways. Fuel dumps erupted in flames. Within minutes, Japanese air power at TR was shattered.

The Japanese managed to get some aircraft airborne, but American fighters shot them down as fast as they appeared. By noon on the first day, the United States had established air superiority over Troo. The second day focused on shipping. American torpedo bombers and dive bombers attacked every ship in the lagoon and every vessel trying to escape. Japanese merchant ships loaded with fuel and ammunition erupted in spectacular explosions.

Warships attempting to flee were hunted down by American battleships and cruisers circling the ATL. Over 2 days, Operation Hailstone destroyed 45 Japanese ships totaling approximately 200,000 tons. Between 250 and 275 Japanese aircraft were destroyed. Vast quantities of fuel supplies were set on fire. All five airfields were severely damaged.

The cost to American forces was 25 aircraft lost and 40 men killed, including 29 air crew and 11 sailors aboard the carrier Intrepid. The raid was one of the most lopsided victories in naval history. More importantly, Operation Hailstone accomplished exactly what it was designed to do. The combined fleet withdrew from Trou immediately. Japanese admirals recognized that Tru was no longer a safe forward operating base.

The fleet pulled back to Palao and then to the home islands. Once the fleet was gone, Truk’s garrison was trapped. American forces did not invade Tru. They did not need to. They seized anywhere at all in the Marshall Islands to the east and established a major base there. They moved west to the Marana Islands, building airfields within bomber range of Japan itself.

Troo sat between these advances, surrounded by American air power and submarines. Japanese supply ships trying to reach Tro were sunk. The garrison slowly began to run out of food, medicine, and ammunition. By late 1944, American pilots called raids on truck milk runs. Just like Rabal, the defenders shot back, but they could not change their situation.

They were prisoners on their own island, watching the war pass them by. The Japanese did not understand what had happened at first. For months, Japanese commanders expected American invasion fleets to appear at both Rabbal and Tru. They waited in their bunkers. They maintained their defensive positions. They rationed their supplies carefully, preparing for sieges that never came.

Slowly the realization set in. The Americans were not coming. They were never coming. All the fortifications, all the preparations, all the resources poured into making these bases impregnable were wasted. The bases were impregnable. They were also irrelevant. General Hoshi Imamura commanded the Japanese garrison at Rabbal.

He was an experienced officer who had fought in China and led successful campaigns in Java and Malaya. He understood modern warfare, but he had not anticipated the American leaprogging strategy. In early 1944, Imamura documented his confusion about American actions. The Allies had surrounded Rabbal with airfields. They bombed the base daily, but they made no move to invade.

Imamura had 110,000 troops ready to fight. His defensive positions were expertly prepared. He was confident he could inflict massive casualties on any invasion force. But the invasion never came. Imamura’s troops began farming to supplement their dwindling food supplies.

They tended gardens inside the defensive perimeter, growing sweet potatoes and vegetables. They fished in the harbor when American aircraft were not overhead. They raised chickens and pigs. It was surreal. They were still at war, but they were not fighting. They were just surviving. Imamura kept his troops disciplined and organized despite the circumstances.

He maintained strict command structure and military protocol. Daily inspections continued. Centuries stood watch over empty approaches. Gun crews manned defensive positions that would never fire at an invasion fleet. Imamura refused to acknowledge publicly that his fortress had become a prison, but privately he understood.

The war was moving on without him. His 110,000 men, superbly trained and equipped for the decisive battle that would never come, were strategically irrelevant. The Japanese high command faced a terrible dilemma. They could not reinforce the bypassed garrisons because Allied submarines and aircraft controlled the sea lanes.

Any attempt to resupply Rabal or Troo would result in transports being sunk and more men drowned. They could not withdraw the garrisons for the same reason. The men were trapped, but they also could not admit this publicly. Japanese propaganda continued to portray Rabal and Tru as vital bastions tying down large allied forces.

The truth was that a relative handful of Allied aircraft and submarines had neutralized hundreds of thousands of Japanese troops without firing a shot in ground combat. At Tro, the garrison faced similar demoralization. Japanese commanders tried to maintain morale by telling their men they were tying down American forces, but this was not true. No American ground forces were tied down at Truk because no American ground forces were there.

A relative handful of aircraft made occasional bombing runs. Submarines patrolled the waters around the atal. That was all. The Japanese defenders at Trou had no one to fight. They maintained their positions. They drilled. They waited for orders that never came. As food supplies dwindled, malnutrition became common. Diseases spread. Men died not from battle wounds, but from starvation and sickness.

The impregnable fortress was killing them slowly without the enemy firing a shot. Japanese naval strategy had always relied on the concept of decisive battle. The Imperial Japanese Navy planned to draw the American fleet into a climactic engagement where superior Japanese training and tactics would destroy the enemy.

Fortified bases like Trrook and Rabal were supposed to support that decisive battle by providing staging areas for the fleet and air bases for long-range strikes, but the Americans refused to cooperate. They did not steam toward the fortified bases looking for a decisive battle. They went around them when the combined fleet sorted to force that decisive battle at the Philippine Sea in June 1944.

American carrier aircraft decimated Japanese air power in what became known as the Great Mariana’s Turkey Shoot. The decisive battle the Japanese wanted turned into a catastrophic defeat. The strategy that had guided Japanese military planning for decades collapsed. The psychological impact on Japanese commanders was profound.

Officers who had spent their entire careers preparing for the next great fleet engagement found their plans obsolete. Garrisons that had trained for years to defend against American amphibious assaults sat idle. The war they had prepared to fight was not the war the Americans brought to them. Some Japanese officers, particularly younger ones, recognized the brilliance of the American strategy.

They understood that bypassing fortified positions and letting them wither was more effective than trying to reduce them through frontal assault. But acknowledging this meant acknowledging that Japan’s entire defensive strategy was flawed. Rabal and Troo were not the only bases bypassed.

The Americans leaprogged past Wiiwak in New Guinea, leaving approximately 55,000 to 65,000 Japanese troops of the 18th Army cut off. They bypassed Caviang in New Ireland. They isolated Wake Island. Each time the pattern was the same. Surround the base with Allied airfields. Cut the supply lines. Leave the garrison to starve. Move on to the next objective.

By mid 1944, hundreds of thousands of Japanese soldiers were trapped on bypassed islands. They consumed supplies but contributed nothing to Japan’s war effort. They could not be withdrawn because Allied submarines and aircraft controlled the sea lanes. Attempting to evacuate them would just result in more ships sunk and more men drowned.

So they stayed where they were, slowly dying of malnutrition and disease while American forces advanced toward Japan. The full strategic brilliance of the leaprogging strategy became clear in the final year of the war. When American forces invaded the Philippines in October 1944, they did so with overwhelming superiority in ships, aircraft, and troops.

If the Americans had fought their way through every Japanese strong point between the Solomons and the Philippines, the campaign would have taken years and cost hundreds of thousands of casualties. By bypassing the strong points, they reached the Philippines in less than 2 years with far fewer losses. The time and lives saved were incalculable.

Marines who survived Terawa and feared dying at Rabbal instead participated in other operations across the Pacific. Some fought at Pelu, Ewoima, or Okinawa. Many survived the war and returned home because strategic planning had evolved beyond frontal assaults on every fortress.

The decision to bypass Rabal and other strongholds meant those men never had to storm beaches that would have killed them. General Douglas MacArthur returned to the Philippines in October 1944, fulfilling his promise to the Filipino people. The campaign to liberate the Philippines was difficult and costly, but MacArthur’s forces prevailed. After the war, MacArthur reflected on the Pacific strategy in his memoirs. He emphasized the leapfrogging approach with particular pride.

He wrote that it exemplified the principle of economy of force. Why spend 10,000 lives taking a fortress when you can make it irrelevant by going around it? The principle sounds obvious in retrospect, but at the time it was revolutionary. Military doctrine for centuries had emphasized reducing enemy strong points. MacArthur and Nimttz realized that in the Pacific with American naval and air superiority, strong points did not need to be reduced. They just needed to be isolated.

Admiral Chester Nimmitz continued to command Pacific forces until Japan’s surrender in August 1945. He presided over the largest naval expansion in history and the most successful naval campaign ever conducted. After the war, Nimitz reflected on what he considered the most important strategic decision of the Pacific campaign. The decision to bypass Rabal made at Quebec in August 1943 set the template for everything that followed. It proved that the leaprogging strategy worked.

It saved countless American lives and shortened the war considerably. The Japanese garrisons at Rabbal and Troo remained in place until Japan surrendered in August 1945. When General Imamura received word of the surrender, he assembled his troops and informed them the war was over. Many wept. They had endured years of privation and isolation, maintaining military discipline in the expectation that they would eventually fight the decisive battle that would turn the war in Japan’s favor.

That battle never came. The war ended and they had not fired a shot in anger for over a year. Imamura surrendered his command to Australian forces in September 1945. The repatriation of his garrison took over 2 years. 110,000 men, the largest bypassed garrison in the Pacific, went home defeated without having fought a major battle.

At Trrook, the surrender came as a relief to many Japanese troops. The garrison had been on near starvation rations for months. Diseases had killed many. When American forces finally arrived to accept the surrender and begin repatriation, they found survivors emaciated and weak. The impregnable fortress had become a death trap for its own defenders. The fortifications remained intact.

The tunnels were still there. The coastal guns could still fire, but none of it mattered. The garrison had been defeated not by superior firepower, but by strategic irrelevance. The leaprogging strategy was not officially recognized as a decisive innovation during the war.

There were no medals awarded specifically for developing the strategy. No monuments were built to commemorate the decision to bypass Rabal, but the impact was unmistakable. By the time American forces reached the Japanese home islands in 1945, they had isolated hundreds of thousands of Japanese troops on bypassed islands.

Those troops consumed food and supplies, but contributed nothing to Japan’s defense. If they had been available to defend Ewima, Okinawa, or the home islands, American casualties would have been far higher. The Rabal garrison alone represented more combat power than the Japanese had available to defend Okinawa.

The bypassed garrisons were Japan’s lost army, trapped on islands that had been turned into prisons by American strategic imagination. After the war, military historians studied the Pacific campaign extensively. The leaprogging strategy became a case study in militarymies around the world. It demonstrated the value of strategic mobility, the importance of naval and air superiority, and the principle that the strongest defense can be rendered useless if it can be bypassed.

Modern military doctrine incorporates these lessons. Commanders are taught to avoid enemy strengths and attack weaknesses. Fortifications are understood to be useful only if the enemy cooperates by attacking them. These principles seem obvious now. They were not obvious in 1943 when American planners first proposed bypassing Rabbol. Many senior officers thought the idea was too risky. Some argued it was cowardly to bypass enemy forces rather than destroy them.

Others worried about leaving strong enemy garrisons in the rear. But MacArthur and Nimmitz understood that the Pacific War would be won by reaching Japan quickly, not by eliminating every Japanese garrison along the way. The fastest route to Tokyo ran past Rabal and Trrook, not through them.

Time spent reducing those fortresses was time the Japanese could use to strengthen defenses closer to the home islands. Lives spent capturing those bases were lives that could not be risked in later battles. Resources expended on unnecessary sieges were resources diverted from the main effort. The mathematics were compelling.

If taking Rabal would have cost 30,000 American casualties in 6 months, bypassing it saved 30,000 lives in 6 months. Those lives could not be replaced. That time could not be recovered. The strategic choice was clear once commanders stopped thinking in terms of territory and started thinking in terms of time and casualties.

The objective was not to own every island in the Pacific. The objective was to defeat Japan as quickly and efficiently as possible. Rabbal today is a town in Papua New Guinea. The tunnels and bunkers the Japanese built still exist. They are tourist attractions now.

Visitors can walk through the underground complexes and see the coastal defense guns still pointed out to sea, waiting for an invasion that never came. The concrete imp placements remain intact. The ammunition storage rooms are empty. The command posts are silent. The airfields are overgrown or converted to civilian use. Simpson Harbor, which once sheltered the combined fleet, now hosts commercial shipping and fishing boats.

It is hard to imagine that this quiet tropical harbor was once the most fortified position in the South Pacific, the lynch pin of Japan’s defensive strategy. A base so powerful that taking it seemed impossible. It was impossible. That is why the Americans did not try. Chuk Lagoon, now known as Chuk Lagoon, is one of the world’s premier wreck diving destinations. The 45 ships sunk during Operation Hailstone rest on the bottom of the lagoon.

Divers explore cargo holds filled with trucks, tanks, ammunition, medical supplies, and personal effects. The merchant ship Fujiawa Maru still holds fighter aircraft in her holds. The submarine tender Rio de Janeiro Maru sits upright on the bottom with artillery pieces visible on her deck. Aircraft wrecks lie scattered across the lagoon floor.

Betty bombers, zero fighters, and other aircraft rest where they crashed 70 years ago. The wrecks are time capsules from February 1944 when American carrier aircraft turned the Gibralar of the Pacific into a graveyard. The defensive positions on the islands are still there. Concrete bunkers, artillery imp placements, tunnels carved into the hills, all intact, all useless.

The fortress that was supposed to protect Japan became a museum to the futility of static defense in the age of air power and mobility. The story of how 110,000 Japanese troops sat in fortified positions while the war moved past them is a story about the difference between tactical strength and strategic relevance. Rabal was tactically impregnable.

Any direct assault would have been a bloodbath, but strategic irrelevance rendered those tactical strengths meaningless. The same was true at Truk and every other bypassed base. The Japanese built fortresses designed to win battles. The Americans fought a war designed to make those battles unnecessary. In the end, the strongest fortress is only as valuable as its position on the strategic map. If you can redraw the map, the fortress becomes irrelevant.

If you can change the nature of the campaign, fixed defenses become liabilities rather than assets. If you can achieve your strategic objectives without engaging the enemy’s strength, then the enemy’s strength becomes his weakness. He has poured resources into positions that do not matter.

He has deployed men to places where they cannot influence the outcome. He has prepared for a war that you are not fighting. This is how innovation happens in war. Not always through new weapons or new technology, but through new thinking about old problems. The problem of fortified islands had one traditional solution. Overwhelming force applied directly until the fortress fell.

MacArthur, Nimits, and their staffs asked if there was another solution. They found one. Go around. Cut them off. Let them starve. Move on. It saved tens of thousands of American lives. It shortened the war. It proved that strategic imagination matters more than tactical strength. The planners who developed this strategy were not celebrated with parades or medals. Most of their names are forgotten.

But the young Americans who came home from the Pacific instead of dying in assaults on Rabbal or Tru owed their lives to strategic thinking that realize the hardest fight to win is the one you never have to fight at all. The lesson transcends World War II.

Every fortress, every defensive position, every prepared defense is only valuable if the attacker cooperates by attacking it. The attacker who refuses to cooperate, who finds another route, who changes the nature of the campaign, holds the initiative. The defender who builds impregnable fortresses without securing the approaches to those fortresses has wasted his resources.

The commander who understands this can win campaigns without fighting the battles his enemy has prepared for. Japan prepared for one war. America fought another. Japan prepared for a decisive naval battle that would destroy the American fleet. America island hopped past Japanese strong points and brought overwhelming force to bear where Japan was weak. Japan concentrated forces in fortresses.

America bypassed the fortresses and cut off their supplies. Japan fought the war they wanted to fight. America fought the war they needed to win. The difference decided the outcome.

News

CH2 They Laughed at America’s Copy — Then 55,000 Packard Merlins Buried the Luftwaffe

They Laughed at America’s Copy — Then 55,000 Packard Merlins Buried the Luftwaffe Recklin, Germany. Winter, 1943. The airfield…

CH2 How One Welder’s “Ridiculous” Idea Saved 2,500 Ships From Splitting in Half at Sea

How One Welder’s “Ridiculous” Idea Saved 2,500 Ships From Splitting in Half at Sea January 16th, 1943. The morning…

CH2 German Engineers Tried to Copy the Sherman Tank—Then Learned Its Real Secret Was Not the Armor

German Engineers Tried to Copy the Sherman Tank—Then Learned Its Real Secret Was Not the Armor August 1942. North…

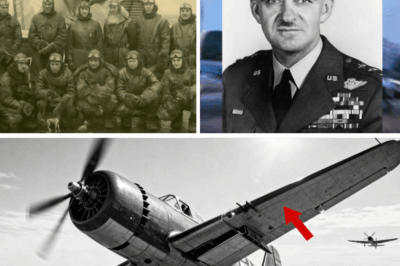

CH2 How One Pilot’s “Forbidden” Flap Setting Made Thunderbolts Climb Faster Than Fw 190s

How One Pilot’s “Forbidden” Flap Setting Made Thunderbolts Climb Faster Than Fw 190s The morning of March 15th, 1944,…

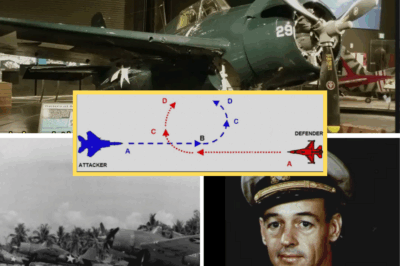

CH2 How One Commander’s “Matchstick” Trick Made 4 Wildcats Destroy Zeros They Couldn’t Outfly

How One Commander’s “Matchstick” Trick Made 4 Wildcats Destroy Zeros They Couldn’t Outfly The morning sky above Wake Island…

CH2 Japanese Pilots Laughed At The F6F Hellcat, Until It Swept Their Zeros From The Sky

Japanese Pilots Laughed At The F6F Hellcat, Until It Swept Their Zeros From The Sky The air above Rapopo…

End of content

No more pages to load