How One Woman’s “Crazy” Coffin Method Saved 2,500 Children From Treblinka in Just 1,000 Days

November 16th, 1940. Ulica Sienna, Warsaw. The autumn air is sharp, carrying the metallic scent of cold brick and the sour smell of fear. On this day, the gates swing shut. A wall, three meters high and topped with barbed wire, has been completed. It runs for eleven miles, a scar of mortar and prejudice carved through the heart of a once-vibrant city.

Inside, in an area of just over one square mile, nearly half a million souls are now trapped. This is the Warsaw Ghetto. And for the world outside the wire, it is a place to be forgotten. But one woman cannot forget. Her name is Irena Sendler, a 30-year-old senior administrator in the Warsaw Social Welfare Department.

She is slight of build, with kind, determined eyes that seem to register everything. For Irena, this moment is not the beginning of the horror, but its confirmation. The logic of evil, made manifest in brick and stone. Her life has been a long preparation for this impossible duty. Born in 1910, she was the daughter of a physician, Stanisław Sendler.

He was one of the few doctors who would treat the poor Jewish families of Otwock, a town near Warsaw. He died of typhus in 1917, contracted from the very patients others refused to see. Before he passed, he had left his young daughter with a simple, unshakeable principle—a rule that would become the compass for her entire existence.

“If you see someone drowning,” he told her, “you must try to save them. Even if you can’t swim.” Now, in 1940, an entire population is drowning. And Irena Sendler, a social worker with a state-issued pass, is about to jump into the water. In the months leading up to the ghetto’s sealing, Irena had already bent the rules to their breaking point.

As the German occupation tightened its grip, she and her colleagues within the department began a shadow operation. They falsified documents, creating thousands of fake case files to funnel money, food, and medicine to Jewish families who had been stripped of their livelihoods and branded with the Star of David. It was a dangerous game of bureaucratic subterfuge, a quiet rebellion waged with ink stamps and forged signatures.

But the wall changes everything. The flow of aid, once a trickle, now faces a dam. The people she was helping are now inmates in the largest, most densely populated prison in modern history. The official line from the occupying forces is clear: the ghetto is a sealed quarantine zone, designed to contain the spread of diseases like typhus. For the Nazis, the disease is both a pretext and a weapon.

Yet this pretext creates an opportunity. The Germans, terrified of an epidemic spilling into the “Aryan” side of Warsaw, need to maintain a semblance of sanitary control within the ghetto. They grant special passes to a handful of non-Jewish Polish workers, including sanitation crews and disease-control specialists.

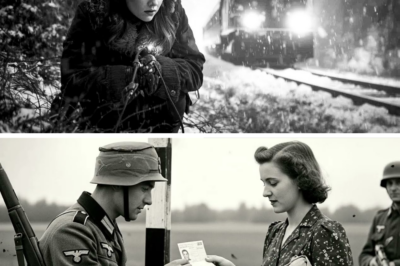

Irena, in her official capacity, petitions her superiors. She argues that as a welfare officer, she must enter the ghetto to inspect sanitary conditions and deliver what meager aid is permitted. She is granted a Kennkarte—an identification pass. It is a small, laminated card, but to her, it is a key. A key to a kingdom of hell.

Her first steps inside are a descent. The Warsaw she knows—a city of parks, cafes, and grand avenues—vanishes the moment she passes the armed guards. Here, the cobblestone streets are choked with a desperate, starving populace. Ten to fifteen people live in apartments built for a single family.

The silence is the most terrifying sound—the hollow, listless quiet of children too weak from hunger to cry. The air is thick with the stench of unwashed bodies, coal smoke, and encroaching death. Every day, she walks these streets, a litany of horror seared into her memory. She sees children with wizened, old faces and swollen bellies.

She sees bodies lying in the street, covered with newspaper until the overburdened corpse collectors can make their rounds. She does what she can, delivering smuggled bread, potatoes, and precious doses of medicine. She wears a Star of David armband in solidarity, a small act of defiance that could get her shot on the spot. But she knows it is not enough. The food runs out.

The medicine is a drop against an ocean of sickness. She is not stopping the drowning; she is merely helping the victims tread water for a few moments longer. One evening, returning to her small apartment outside the walls, the lesson of her father echoes with a new, terrible clarity. The children. They are the most vulnerable. They are the ones with no future in this man-made inferno.

Saving them isn’t about smuggling bread. It is about smuggling the children themselves. It is a thought so audacious, so profoundly dangerous, that it feels like madness. It would mean spiriting them past Nazi guards, finding them new homes, giving them new names, and erasing their identities to keep them alive. It would mean certain death if she were caught.

She looks at her hands, the hands of a social worker, not a soldier. She cannot swim. But the children are drowning. And she knows she has no choice but to try. The decision, once made, crystallizes into a plan. But Irena knows she cannot do this alone. A lone swimmer would be pulled under immediately. She needs a fleet of lifeboats.

Continue below

November 16th, 1940. Ulica Sienna, Warsaw. The autumn air is sharp, carrying the metallic scent of cold brick and the sour smell of fear. On this day, the gates swing shut. A wall, three meters high and topped with barbed wire, has been completed. It runs for eleven miles, a scar of mortar and prejudice carved through the heart of a once-vibrant city.

Inside, in an area of just over one square mile, nearly half a million souls are now trapped. This is the Warsaw Ghetto. And for the world outside the wire, it is a place to be forgotten. But one woman cannot forget. Her name is Irena Sendler, a 30-year-old senior administrator in the Warsaw Social Welfare Department.

She is slight of build, with kind, determined eyes that seem to register everything. For Irena, this moment is not the beginning of the horror, but its confirmation. The logic of evil, made manifest in brick and stone. Her life has been a long preparation for this impossible duty. Born in 1910, she was the daughter of a physician, Stanisław Sendler.

He was one of the few doctors who would treat the poor Jewish families of Otwock, a town near Warsaw. He died of typhus in 1917, contracted from the very patients others refused to see. Before he passed, he had left his young daughter with a simple, unshakeable principle—a rule that would become the compass for her entire existence.

“If you see someone drowning,” he told her, “you must try to save them. Even if you can’t swim.” Now, in 1940, an entire population is drowning. And Irena Sendler, a social worker with a state-issued pass, is about to jump into the water. In the months leading up to the ghetto’s sealing, Irena had already bent the rules to their breaking point.

As the German occupation tightened its grip, she and her colleagues within the department began a shadow operation. They falsified documents, creating thousands of fake case files to funnel money, food, and medicine to Jewish families who had been stripped of their livelihoods and branded with the Star of David. It was a dangerous game of bureaucratic subterfuge, a quiet rebellion waged with ink stamps and forged signatures.

But the wall changes everything. The flow of aid, once a trickle, now faces a dam. The people she was helping are now inmates in the largest, most densely populated prison in modern history. The official line from the occupying forces is clear: the ghetto is a sealed quarantine zone, designed to contain the spread of diseases like typhus. For the Nazis, the disease is both a pretext and a weapon.

Yet this pretext creates an opportunity. The Germans, terrified of an epidemic spilling into the “Aryan” side of Warsaw, need to maintain a semblance of sanitary control within the ghetto. They grant special passes to a handful of non-Jewish Polish workers, including sanitation crews and disease-control specialists.

Irena, in her official capacity, petitions her superiors. She argues that as a welfare officer, she must enter the ghetto to inspect sanitary conditions and deliver what meager aid is permitted. She is granted a Kennkarte—an identification pass. It is a small, laminated card, but to her, it is a key. A key to a kingdom of hell.

Her first steps inside are a descent. The Warsaw she knows—a city of parks, cafes, and grand avenues—vanishes the moment she passes the armed guards. Here, the cobblestone streets are choked with a desperate, starving populace. Ten to fifteen people live in apartments built for a single family.

The silence is the most terrifying sound—the hollow, listless quiet of children too weak from hunger to cry. The air is thick with the stench of unwashed bodies, coal smoke, and encroaching death. Every day, she walks these streets, a litany of horror seared into her memory. She sees children with wizened, old faces and swollen bellies.

She sees bodies lying in the street, covered with newspaper until the overburdened corpse collectors can make their rounds. She does what she can, delivering smuggled bread, potatoes, and precious doses of medicine. She wears a Star of David armband in solidarity, a small act of defiance that could get her shot on the spot. But she knows it is not enough. The food runs out.

The medicine is a drop against an ocean of sickness. She is not stopping the drowning; she is merely helping the victims tread water for a few moments longer. One evening, returning to her small apartment outside the walls, the lesson of her father echoes with a new, terrible clarity. The children. They are the most vulnerable. They are the ones with no future in this man-made inferno.

Saving them isn’t about smuggling bread. It is about smuggling the children themselves. It is a thought so audacious, so profoundly dangerous, that it feels like madness. It would mean spiriting them past Nazi guards, finding them new homes, giving them new names, and erasing their identities to keep them alive. It would mean certain death if she were caught.

She looks at her hands, the hands of a social worker, not a soldier. She cannot swim. But the children are drowning. And she knows she has no choice but to try. The decision, once made, crystallizes into a plan. But Irena knows she cannot do this alone. A lone swimmer would be pulled under immediately. She needs a fleet of lifeboats.

She turns first to the people she trusts most: her small circle of colleagues from the Social Welfare Department. Ten of them, mostly women, who had already risked their careers and lives smuggling aid. They meet in secret, in shadowed apartments, speaking in whispers. When Irena lays out her proposal—not to aid children within the ghetto, but to extract them entirely—the room falls silent. The risk is astronomical.

It is a death sentence for every single one of them if discovered. But in the faces of Jadwiga Piotrowska, Janina Grabowska, and the others, Irena sees the same grim resolve as her own. The conspiracy of compassion is born. Their first challenge is logistics. How does one move a child through a guarded checkpoint? The answer, Irena realizes, lies in exploiting the very systems the Germans have created.

Her ambulance is the first tool. She begins driving it into the ghetto, officially on sanitary missions. But on the return journey, the vehicle carries a secret passenger. A small child, sedated with a mild barbiturate, might be tucked into a large medical bag.

An older child could be hidden under a stretcher, covered by a blanket, pretending to be a typhus victim—a disease so feared by the guards that they often wave the ambulance through with minimal inspection. On one occasion, Irena even trains her dog to bark furiously at any German who approaches the passenger side, creating a diversion to cover the sound of a rustling sack or a stifled whimper from the back.

But the ambulance can only carry one or two at a time. The need is overwhelming. The network must grow. In the late summer of 1942, a pivotal development occurs. The Polish government-in-exile formally establishes the Council to Aid Jews, codenamed “Żegota.

” It is a unique organization in occupied Europe—an underground institution sponsored by the state, dedicated solely to saving Jews. Irena is recruited to direct its newly formed children’s section. Her codename becomes “Jolanta.” With Żegota’s backing, her operation expands exponentially. She now has access to funds smuggled from London, a network of printers for forging documents, and connections to other resistance cells.

“Jolanta” becomes the central hub of a sprawling, clandestine enterprise. Her network of ten women blossoms into more than two dozen dedicated operatives. They are liaisons, couriers, scouts, and guardians. They identify families willing to hide a child, secure new birth certificates, and arrange transportation. The methods become more daring, more varied.

The old Warsaw courthouse, which straddled the ghetto boundary, becomes a key transit point. Children are led through its cellars and secret passages, entering as one identity and emerging on the other side as another. For the smallest infants, the methods are the most desperate. They are carried out in potato sacks, hidden in carpenters’ toolboxes, and even placed inside coffins alongside the bodies of the dead.

Perhaps the most harrowing route is through the city’s sewer system. It is a journey into utter darkness. Guides lead small groups of children through the foul, labyrinthine tunnels beneath the city. They wade through waist-deep, freezing water, the stench overwhelming, the only light coming from a flickering carbide lamp.

The children are instructed not to make a sound, their footsteps muffled by the flowing filth. For them, it is a terrifying odyssey, a literal passage through the underworld, leaving one hell in the hope of finding a heaven they cannot yet imagine. For Irena, the most difficult part is not the logistics, but the conversations. She must go to the parents, the mothers and fathers clinging to their children in squalid rooms, and ask them for the ultimate act of love: to give them away.

She meets them in secret, her heart aching with every word. She explains the plan, the risks, the sliver of hope. She never lies. “I cannot guarantee your child will live,” she tells them, her voice steady despite the tremor in her soul. “But I can guarantee that if they stay here, they will die.” Some refuse, unable to bear the separation.

But most, seeing the slow, inevitable death surrounding them, make the agonizing choice. They dress their child in their best clothes, hand Irena a small memento—a photograph, a silver spoon, a lock of hair—and say a goodbye they know is almost certainly final. Irena watches as a mother kisses her daughter’s forehead one last time, her tears falling on the child’s face, before turning away, her silence a scream of pure anguish.

With each rescued child, Irena feels a dual emotion: a surge of triumph and a crushing weight of responsibility. Because saving them from the ghetto is only the first step. For each child, she creates a new identity. A blond, blue-eyed child might be taught Catholic prayers and placed with a Polish family in a rural village.

A child with darker features might be sent to a convent, where the nuns can shelter them from prying eyes. Every detail must be perfect. The forged baptismal certificate, the fabricated family history, the new name the child must answer to without hesitation. Yet Irena refuses to let their true identities vanish forever. She begins a secret archive. On thin slips of tissue paper, she writes down the child’s original name and their new, adopted one.

She lists their parents, their last known address in the ghetto, and where they have been placed. This is her sacred promise to the parents: that if any of them survive, she will have a way to reunite them. She rolls the small scraps of paper tightly, seals them inside two glass jars, and buries them in her neighbor’s garden, beneath a young apple tree. A secret ledger of lost children, waiting for a spring that seems impossibly far away.

By the spring of 1943, the gears of the Final Solution are grinding at full speed in Warsaw. The Great Deportation action of the previous summer had emptied the ghetto of over a quarter-million people, sent to the gas chambers of Treblinka. The remaining population knows its fate.

A desperate, heroic, and doomed uprising begins on April 19th, as Jewish fighters take up arms against the SS. The ghetto becomes a warzone. Smoke billows across the city, a black funeral shroud visible for miles. The sounds of machine-gun fire and explosions are a constant, brutal drumbeat. For Irena and her network, the uprising is a catastrophe.

It makes their work infinitely more dangerous. The German cordon around the ghetto is now absolute, a ring of steel and fire. Smuggling becomes nearly impossible. The few remaining routes—the sewers, the courthouse cellars—are under intense surveillance. The SS, enraged by the resistance, are merciless. Any Pole caught aiding a Jew is executed on the spot, along with their entire family.

Yet, “Jolanta” does not stop. She and her operatives redouble their efforts, driven by the knowledge that time has run out. They work with a frantic, desperate energy, pulling the last possible children from the inferno. They use the chaos of the fighting as cover, exploiting moments of distraction to spirit people out.

The children who emerge are no longer just starving; they are traumatized by war, covered in the dust of collapsing buildings, their eyes reflecting the flames they have just escaped. The network itself is under immense strain. Close calls become a daily occurrence. Couriers are stopped and searched. Safe houses are raided.

One of Irena’s key lieutenants is arrested, and the entire network holds its breath, fearing she will break under torture. She does not. The conspiracy of compassion holds firm, bound by a loyalty stronger than fear. Irena, as the central coordinator, is the most exposed. She is constantly moving, never sleeping in the same place for more than a few nights.

Her official work at the Welfare Department is her cover, but the Gestapo, the Nazi secret police, are not fools. They are aware of a highly organized Polish underground aiding Jews. They are hunting for its leaders. And the name Irena Sendler has begun to appear in their intelligence chatter. The inevitable happens on the morning of October 20th, 1943.

At dawn, loud, violent knocking echoes through the apartment where she is staying. Before she can even react, the door splinters open. Four Gestapo agents storm in. The raid is brutal and efficient. They tear the apartment apart, searching for incriminating evidence. Irena’s mind races. A fellow operative is waiting for her downstairs with a list of rescued children—a list that would condemn dozens of Polish families to death.

Thinking fast, Irena shoves the list into the hands of a friend in the apartment, who hides it in her underclothing as the agents are distracted. They find nothing concrete, but their suspicions are enough. Irena is arrested. She is taken to the Gestapo headquarters on Szucha Avenue, a building that has become synonymous with torture and death. From there, she is transferred to the infamous Pawiak Prison.

For three months, she endures a living nightmare. She is interrogated relentlessly. They want names. They want the structure of Żegota. They want the location of the hidden children. Irena is beaten. Her feet and legs are broken. Her shoulders are dislocated. She is tortured until she passes out, is revived, and the process begins again. But she does not talk.

The faces of the children she saved, the promises she made to their parents, are a shield around her mind. The code name “Jolanta” is a ghost they cannot catch. She gives them nothing. She tells her captors she knows nothing, that she is just a simple social worker. Her defiance only fuels their rage. Finally, they give up. Irena Sendler is sentenced to death by firing squad.

On the scheduled day of her execution, she is called from her cell. She walks on her broken feet, supported by guards, expecting to be taken to the prison courtyard. But instead of leading her to her death, the guards take her to an administrative office. A German officer looks up from a list, finds her name, and announces curtly that she is being released.

It is a miracle born of bribery. Żegota had not abandoned its leader. The Polish underground had managed to bribe a Gestapo official. A huge sum of money had been paid, and Irena’s name was quietly added to a list of prisoners being transferred. On paper, she was executed. Her name was posted on public bulletins among the dead.

But in reality, a guard led her out a back door and left her, broken and bleeding, on a quiet Warsaw street. She is a ghost. Officially dead, she must now live in the deepest shadows. Her work as “Jolanta” is over; to continue would risk not only her life but the entire network she built.

She goes into hiding, moving from one safe house to another, nursing her wounds, her heart heavy with the work left undone. The war rages on. Warsaw is systematically destroyed by the Germans in the aftermath of the 1944 Uprising. But as she hides, she clings to one singular hope. The hope buried in two small glass jars, under an apple tree in a friend’s garden. A fragile, papery record of 2,500 names.

2,500 stolen childhoods. 2,500 chances for a future. The war had taken her strength, her freedom, and nearly her life. But it had not taken her list. The war in Europe ends in May 1945. Warsaw is a wasteland, a sea of rubble where a city once stood. Irena Sendler, no longer a ghost, emerges from the shadows.

She is physically frail, the damage from her time in Pawiak Prison leaving her with a permanent limp. But her spirit is unbroken, her purpose singular. The war is over, but her mission is not. It is time to dig up the jars. She returns to the garden, to the small apple tree that has become the silent guardian of her secret. The earth is cold and damp as she digs.

Her hands, which once soothed frightened children, now search for the fragile archive of their existence. When her fingers finally touch the cool glass of the first jar, a wave of profound relief washes over her. The second jar is unearthed moments later. The lists are safe. The names are not lost. Now, the most arduous task begins: the work of memory and reunion.

With the jars in hand, Irena and her surviving network members attempt to track down the children they saved. They are scattered across Poland, living under new names, many too young to remember their original families. Irena’s meticulously kept records are their only guide. They begin the painstaking process of cross-referencing the names, contacting the convents, orphanages, and foster families.

The joy of a successful reunion is immense, a flicker of light in the post-war darkness. A child, now a few years older, is brought to a surviving aunt or uncle. A name, long-buried, is spoken aloud, and a flicker of recognition crosses a young face. But these moments are heartbreakingly rare. For the vast majority of the 2,500 children on her list, there is no one to return to.

Their parents, their entire families, have been murdered in the ghetto, in Treblinka, in the machinery of the Holocaust. Irena is forced to deliver the devastating news over and over: “Your parents are gone. You are alone.” She becomes the keeper of their orphaned stories, the last living link to the families they will never know.

Many of the children remain with their adoptive Polish families, their Jewish heritage a secret they carry into their new lives. As Poland falls under the shadow of a new occupier—the Soviet Union—Irena’s story, and the story of Żegota, is deliberately suppressed. The new Communist regime is hostile to narratives of Polish wartime heroism that do not fit its political agenda.

The Home Army and other independent resistance groups are portrayed as reactionary, their achievements erased from official histories. Irena, because of her connection to the Polish government-in-exile, is viewed with suspicion. She is interrogated by the secret police of the new government, her loyalty questioned.

Her heroism, once a capital crime under the Nazis, is now a political liability under the Communists. And so, Irena Sendler fades into obscurity. She marries, has children, and returns to a quiet life, working in social welfare and education. The world she saved moves on, and for decades, her extraordinary courage remains a secret known only to a few.

The children she rescued grow up, build their own lives, and the story of “Jolanta” and the jars buried under the apple tree is consigned to the silence of the Cold War. She lives a modest, unassuming life in a Warsaw apartment, a quiet heroine hidden in plain sight. She rarely speaks of the war, the memories too painful, the political climate too dangerous. The world has forgotten her.

But history has a long memory. In 1999, in the small town of Uniontown, Kansas, a group of high school students—Megan Stewart, Elizabeth Cambers, and Sabrina Coons—are assigned a history project. Their teacher gives them a cryptic clipping from a 1994 issue of U.S. News & World Report that mentions an “Irena Sendler” who “saved 2,500 children.

” The students are skeptical. They have studied the Holocaust. They know the name Oskar Schindler. If a woman had saved more than twice as many people as Schindler, surely they would have heard of her. Their search for information turns up almost nothing. They find no books, no articles. Most Holocaust archives have no record of her.

They begin to believe the number is a misprint. But their curiosity is piqued. They dig deeper, sending emails, writing letters, and scouring the nascent internet. They eventually locate a Jewish organization that confirms the story is true. And to their astonishment, they learn something else: Irena Sendler is still alive. She is 89 years old and living in Warsaw.

The students write a play about her life, titled “Life in a Jar,” in honor of her buried lists. The play becomes a local sensation, then a national one. Their humble history project has unearthed one of the great, untold stories of the Second World War. The world, which had forgotten Irena Sendler for half a century, is about to learn her name.

The silence is finally broken. And for an elderly woman in Warsaw, the past comes rushing back, bringing with it a recognition she never sought, but so profoundly deserved.

News

CH2 How One Jewish Fighter’s “Mad” Homemade Device Stopped 90 German Soldiers in Just 30 Seconds

How One Jewish Fighter’s “Mad” Homemade Device Stopped 90 German Soldiers in Just 30 Seconds September 1942. Outside Vilna,…

CH2 How One Brother and Sister’s “Crazy” Leaflet Drop Exposed 2,000 Nazis in Just 5 Minutes

How One Brother and Sister’s “Crazy” Leaflet Drop Exposed 2,000 Nazis in Just 5 Minutes February 22nd, 1943. Stadelheim…

CH2 The Forgotten Battalion of Black Women Who Conquered WWII’s 2-Year Mail Backlog

The Forgotten Battalion of Black Women Who Conquered WWII’s 2-Year Mail Backlog February 12th, 1945. A frozen ditch near…

CH2 How a Ranch-Hand Turned US Sniper Single-Handedly Crippled Three German MG34 Nests in Under an Hour—Saving 40 Men With Not a Single Casualty

How a Ranch-Hand Turned US Sniper Single-Handedly Crippled Three German MG34 Nests in Under an Hour—Saving 40 Men With Not…

CH2 The Untold Story of Freddy Oversteegen, the 14-Year-Old Who Lured N@zis to Their Deaths on Her Bicycle in Occupied Netherlands – The Untold WW2 Story

The Untold Story of Freddy Oversteegen, the 14-Year-Old Who Lured N@zis to Their Deaths on Her Bicycle in Occupied Netherlands…

CH2 “‘You’ll Never See Them Coming’: How American Marines Turned Jungle Terror Into Lethal Precision—The Untold Story of Countering Japan’s Deadliest Snipers in the Pacific”

‘You’ll Never See Them Coming’: How American Marines Turned Jungle Terror Into Lethal Precision—The Untold Story of Countering Japan’s Deadliest…

End of content

No more pages to load