How One Quiet Officer Saw the Trap No One Else Could – And Saved Patton’s Army in the Ardennes When Everyone Was Blind

December 1944. The world was drunk on the illusion of victory. London’s newspapers were splashed with headlines proclaiming the end of the war. Parisian cafés overflowed with champagne and laughter. In Washington, generals were already planning the ticker-tape parades down Pennsylvania Avenue. The Nazi war machine, they thought, was a ghost of its former self—starved of fuel, broken, and retreating.

They were wrong.

Alone in a small, dimly lit office in Northern France, Colonel Oscar Caul stared at a sprawling map of the Ardennes forest. The map wasn’t just ink on paper—it was a warning, a prelude to disaster. While the world celebrated, Caul saw the enemy that no one else could. Quarter of a million German soldiers, hidden among the pines and frozen roads, waiting like predators for the unsuspecting American forces to stumble blindly into their trap.

Caul didn’t need the spotlight. Unlike General George S. Patton, who thrived on attention, who carried ivory-handled pistols with the confidence of a Roman emperor reborn, Caul preferred silence. He spoke softly, almost never raised his voice, and his thick glasses perpetually slipped down his nose as he pored over reconnaissance reports. While Patton sought glory and headlines, Caul sought truth.

The Ardennes was considered a backwater, a “quiet sector” where tired units were sent to rest, to recuperate before moving to the front lines. Freshmen soldiers learned the ropes here, veterans took it easy. Safety, they thought, was assured. But Caul didn’t believe in safety. Safety was an illusion, a trap waiting to snap shut.

Every morning, he traced the positions of German divisions with a grease pencil on the massive map. Every tank battalion, every rail line, every forested ridge—it all mattered. But by late October, the usual markers vanished. The Sixth Panzer Army disappeared. The Fifth Panzer Army disappeared. No radio chatter. No movement in the skies. The SS armored divisions, the Tigers, the Panthers—battle-hardened veterans of the Eastern Front—had vanished as if swallowed by the earth.

At Supreme Headquarters, optimism reigned. The generals toasted the retreat, congratulated themselves on their calculations, and assumed the enemy was licking its wounds. But Caul knew better. Armies don’t just vanish. When the most feared armored divisions in history disappear from the map, it is not weakness—it is cunning.

He dug deeper. He ignored cheerful telegrams from London. He ignored the reports of supply shortages and bombed-out factories that supposedly rendered Germany powerless. Instead, he studied the small, overlooked details. Freight trains moving westward under the cover of night, German civilians evacuated from villages near the Arden, roads cleared of obstacles—all signs that the quiet sector was not safe at all, but alive with preparation.

And the weather… a massive storm front barreling in from the Atlantic. Snow and fog thick enough to blind the Allied air forces. Caul connected the dots: the Arden was a stage, and the Germans were actors ready to strike when the Americans were most vulnerable.

But knowing the danger was only half the battle. Convincing anyone else was another.

December arrived, and arrogance gripped the Allied high command. They were obsessed with racing eastward, pursuing what they thought was a retreating enemy. When Caul warned them, his concerns were met with laughter. “Impossible,” they said. “They don’t have fuel, they don’t have tanks, they can’t attack.”

Caul didn’t argue. He marked the Arden with a thick red question mark: enemy concentration. He whispered warnings into the void. The wolf was real, and it was breathing down their necks.

Continue below

December 1944. The war was supposed to be over. In London, the newspapers were printing victory headlines. In Paris, soldiers were drinking champagne. In Washington, generals were already planning the victory parade. They believed the Nazi war machine was broken, out of fuel, and incapable of fighting back.

They were wrong. While the entire world celebrated, one man sat alone in a dark room in France, staring at a map that whispered a terrifying secret. He saw what the generals ignored. He saw the trap. He saw a quarter of a million German soldiers hiding in the forest, waiting to slaughter the American army. And he knew that if he didn’t convince his commander to turn around, the war wouldn’t end by Christmas.

It would end in a massacre. This is the story of the deadliest silence in World War II. General George S. Patton was the loudest man on the Western Front. He was the god of armored warfare, a man who carried ivory-handled revolvers and believed he was a reincarnated warrior from ancient Rome.

He moved fast, struck hard, and never looked back. To the public, he was the hero who liberated France. But in the winter of 1944, Patton wasn’t the one who saved the Third Army. That honor belonged to a man nobody knew. A man who wore thick glasses, spoke in a whisper, and spent his days buried under stacks of paper. Colonel Oscar Caul.

Caul was Patton’s brain. He was the chief of intelligence. And while Patton was looking for glory, Caul was looking for ghosts. The Allied front line stretched for hundreds of miles. But there was one sector everyone ignored, the Arden. It was a ghost sector, a dense, frozen forest of pine trees and narrow roads. The American commanders called it a nursery. They sent tired units there to rest.

They sent green units there to learn the ropes. It was quiet. It was safe. It was the last place on Earth anyone expected a tank attack. But Oscar Caul didn’t believe in safe places. Every morning he stood in front of his massive situational map in Nazi France. He used grease pencils to mark the location of every known German division.

He tracked them like a hunter tracking a wounded animal. But in late October, the tracks stopped. The sixth Panzer army vanished. The fifth Panzer Army vanished. These weren’t just random units. These were Hitler’s executioners, the SS armored divisions, the Tigers, the Panthers, the veterans of the Eastern Front.

One day they were fighting in the north and the next day they were gone. Radio traffic from the German side went dead. The skies over the German border were empty. At Supreme Headquarters, the top allied generals smiled. They said the Germans were retreating. They said the enemy was licking its wounds, pulling back into the fatherland to survive the winter. They saw the silence as weakness. Ko saw the silence as a weapon.

He knew that armies don’t just evaporate. If the most dangerous tank divisions in the world weren’t on the map, it meant they were hiding. And if they were hiding, they were preparing to kill. Ko started digging. He ignored the optimistic reports coming from London. He focused on the tiny, boring details that everyone else threw in the trash.

He looked at the reconnaissance photos of the German rail lines. They showed heavy freight trains moving west toward the front under the cover of darkness. Why would a retreating army send supplies forward? He looked at the reports from the intricate network of spies. They mentioned that German towns near the Arden were being evacuated. Civilians were being moved out.

Why? To clear the roads for something big. He looked at the weather forecast. A massive storm front was moving in from the Atlantic. It brought heavy snow and thick fog. It was the kind of weather that grounded airplanes. And without air support, the American Sherman tanks were sitting ducks for the German Tigers.

Ko put the puzzle together. It wasn’t a retreat. It was an assembly. The Germans were using the ghost sector against them. They were gathering an armada of steel in the one place the Americans weren’t looking. They were waiting for the fog to blind the Allied Air Force. And they were planning to strike exactly when the Americans were most relaxed.

It was a master stroke of deception and Oscar Ko was the only man in Europe who saw it coming. But seeing the danger is only half the battle. The harder part is getting someone to believe you. In early December, the atmosphere at Allied Headquarters was arrogant. The pursuit mentality had taken over. Everyone was obsessed with racing to the Ryan River.

When Ko tried to raise the alarm, he was met with laughter. Other intelligence officers called him a pessimist. They pointed to the fuel shortages in Germany. They pointed to the destroyed factories. They said, “The Germans can’t attack. It’s mathematically impossible.” Ko didn’t argue. He didn’t shout. He just kept updating his map.

He drew a big red question mark over the Arden. He labeled it enemy concentration. He was the boy who cried wolf. But the wolf was real, and it was breathing down their necks. By December 9th, the signs were undeniable. Ko realized he was running out of time. The storm was coming. If the Third Army kept pushing east, they would expose their flank. They would be cut off.

He had to make a move. He had to confront Patton. Walking into Patton’s office was not for the faint of heart. The general was known to scream at subordinates, to humiliate officers who brought him bad news. He wanted to attack, not defend. Telling Patton to stop his advance was like telling a shark to stop swimming. Ko walked in. He laid his map on the desk. The room was quiet.

He didn’t use dramatic words. He simply pointed to the empty spaces. He showed the rail movements. He showed the radio silence. He explained the weather. General Ko said softly. The capability is there. They are going to hit us here. He pointed to the Arden. Patton stared at the map. The room held its breath. The staff officers waited for the explosion. They waited for Patton to throw Koke out of the room for being a coward.

But Patton didn’t scream. He walked to the window and looked out at the gray sky. He knew Ko. He knew that this quiet man didn’t guess. If Ko said the Germans were there, they were there. Patton turned around. It’s the perfect setup, he muttered. They want to cut us in half. In that moment, Patton did something that separates great commanders from average ones. He killed his ego.

He abandoned his plan to attack East. He looked at Ko and asked, “What do we need to do?” Ko had the answer ready. We need to prepare a counter strike. We need to be ready to turn the army 90° north to hit them in the flank when they come out of the woods. It sounds simple on paper. In reality, it was a logistical nightmare.

Turning an army of 250,000 men, thousands of tanks, and tons of supplies in the middle of winter is impossible. It requires new maps, new fuel depots, new communication lines. It’s like trying to turn a speeding freight train on a dime. Patton didn’t hesitate. Do it, he said. Start the planning. Don’t tell Eisenhower yet.

He won’t believe us. Just get it ready. For the next 7 days, the Third Army lived a double life. To the outside world, they were still preparing to invade Germany. But behind closed doors, Ko and the staff were working 20our days. They were drafting a secret playbook. They were identifying which roads could hold the weight of tanks in the snow. They were stockpiling gasoline.

They were creating a ghost army within the real army, ready to pivot north at a specific code word. Meanwhile, 60 mi to the north, the trap was ready to snap shut. The American soldiers in the Ardens were oblivious. These were the men of the 106th Golden Lions and the 28th Infantry. Many were teenagers, fresh from boot camp.

They sat in their foxholes, freezing, complaining about the lack of winter boots. They wrote letters home about the Christmas presents they hoped to receive. They couldn’t hear the engines revving up just a few miles away. They couldn’t see the white camouflage cloaks of the German stormtroopers moving through the trees.

They didn’t know that 1,600 artillery guns were aimed directly at their heads. The silence in the forest was heavy. It was the deep breath before the scream. On the night of December 15th, Oscar Ko sat in his office. The reports had stopped coming in completely. The map was finished. The math was done.

There was nothing left to analyze. He took off his glasses and rubbed his eyes. He was exhausted. He had done everything he could. He had warned the one man who would listen. Now all he could do was wait. December 16th, 1944, 5:30 a.m. The world ended. The horizon exploded. The sky turned orange.

The roar of the German artillery was so loud it could be heard in Paris. Thousands of shells rained down on the sleeping American boys in their foxholes. The trees shattered. The earth shook. And then came the tanks. Out of the mist, the German panzers rolled forward. They were unstoppable. They crushed the thin American line in minutes. Confusion rained. Phone lines were cut.

Command posts were overrun. Panic spread like a virus up the chain of command. Generals were waking up to reports of massive breakthroughs. Where did they come from? They screamed. Who are they? The German offensive, the Battle of the Bulge, had begun. By midday, the situation was catastrophic. The Germans were punching a massive hole in the Allied line.

They were driving for the coast. If they succeeded, they would split the British and American armies. They would capture the port of Antwerp. they could force a negotiated peace. Eisenhower called an emergency meeting at Verdun. The mood in the room was grim. The generals were pale. They were looking at maps that showed red arrows swarming over their positions.

Eisenhower looked at his commanders. I need someone to attack the southern flank of this bulge, he said. I need someone to stop them. He looked at Patton. George, how long will it take you to turn your army around and attack? The other generals did the math in their heads. To disengage from a battle, turn around, drive a 100 miles through a blizzard, and launch a new attack, it would take at least 4 days, maybe a week. Patton didn’t look at his notes.

He didn’t look at his staff. He looked Eisenhower in the eye. I can attack with three divisions in 48 hours, Patton said. The room went silent. Some of the British officers laughed. They thought he was boasting. They thought he was insane. You cannot move an army that fast. It breaks the laws of physics.

Don’t be a fool, George, someone said. But Patton wasn’t being a fool. He wasn’t guessing. He lit a cigar and smiled. I have the plans already written, Patton said. My staff has been working on them for a week. The code name is Gabriel. I just need to make a phone call. The other generals were stunned. They didn’t know about the secret meetings. They didn’t know about the ghost maps.

They didn’t know about Oscar Caul. While the rest of the Allied command was paralyzed by shock, Patton walked to the telephone. He called his headquarters. He spoke three words. Play ball, Gabriel. And just like that, the miracle began. In the middle of the worst winter in Europe’s history, the Third Army performed the impossible.

133,000 tanks and trucks pulled out of the line. They turned 90°. They drove north into the teeth of the blizzard. The roads were sheets of ice. The wind was cutting through the soldiers coats like knives. But they moved. They moved day and night.

The Germans, who were celebrating their breakthrough, looked at their flanks and saw nothing but empty snow. They thought they were safe. They thought Patton was stuck in the south. They had no idea that a freight train of steel was barreling towards them. By December 22nd, Patton’s tanks smashed into the German flank. The element of surprise was total. The hunters became the hunted. The German advance stalled. The pressure on the trapped American units began to lift.

And at the center of the storm was the town of Baston. Inside the town, the 101st Airborne paratroopers were surrounded. They were out of food. They were running out of ammunition. They were freezing. The German commander had demanded their surrender. The American commander had replied with one word, nuts.

They were holding on by their fingernails. They were praying for a miracle. And on the morning of December 26th, they saw it. Through the trees, a Sherman tank broke through the German lines. Then another, then another. It was Patton’s fourth armored division. The siege was broken. The bulge was deflated. The German gamble had failed. It was one of the greatest military feats in history.

A maneuver that is still studied in war colleges today. The speed, the precision, the audacity. But when the history books were written, the cameras focused on Patton. They focused on his speeches. They focused on the tanks. Nobody took a picture of the quiet man in the back of the room. Nobody interviewed Colonel Oscar Caul. He simply went back to his desk.

He took down the map with the red question mark. He filed away the reports on the sixth panzer army. He cleaned his glasses and he started working on the next day’s intelligence. He didn’t need the glory. He knew what he had done.

He knew that thousands of men were going home to their wives and children because he had refused to look away from the darkness. But the story doesn’t end with the victory. Because sometimes being right is dangerous and sometimes the man who saves the army is the one the army wants to forget. After the war, a strange thing happened. You would think Oscar Caul would be celebrated. You would think he would be promoted to the highest levels of the Pentagon.

Instead, he was pushed aside. Why? Because institutions hate being told they were wrong. Cox’s existence was a reminder of the massive failure of the Allied high command. Every time they looked at him, they were reminded that they had walked into a trap. They were reminded that they had been arrogant.

So while Patton became a legend, [ __ ] became a footnote. But in the years that followed, the soldiers who fought in the Bulge began to learn the truth. They learned that their survival wasn’t just luck. It wasn’t just Patton’s guts. It was Cox’s brain. And this brings us to the most important question of all. Not about war, but about life.

We all have a patent in our lives. The loud voice, the confident leader, the one who wants to charge ahead. And we love them for it. But who is your [ __ ] Who is the person in your life who sits in the corner and tells you the truth you don’t want to hear? The person who points out the red flags.

The person who whispers a warning when everyone else is cheering. It’s easy to listen to the people who tell us we are winning. It’s easy to listen to the people who say everything is going to be fine. It takes courage to listen to the ghost. Oscar Caul died in 1970. He never sought fame, but his legacy is written in the blood of the men he saved.

He proved that in a world of noise, the most powerful weapon is silence, and that sometimes the only thing standing between victory and disaster is one man looking at a map and refusing to lie. So the next time you see a statue of a general or a CEO or a leader standing tall, look at the shadows behind them. That’s where the real work is done. That’s where the ghosts live.

And if you listen closely, you might just hear them whispering the truth. The calendar on the wall said December 16th, 1944. It was 5:30 in the morning. The forest of the Arden was pitch black and silent. The American soldiers in their foxholes were sleeping. They were dreaming of home, of Christmas turkeys and warm fires. And then the world ended. It didn’t start with a single shot.

It started with the apocalypse. 1600 German artillery guns opened fire at the exact same second. The horizon turned into a solid wall of orange fire. The ground shook with such violence that men were thrown out of their sleeping bags. Trees that had stood for a hundred years were snapped like matchsticks.

The air turned into a blender of jagged steel and splintered wood. This was not a probe. This was the hammer of God coming down on the 106th Infantry Division. For the young Americans on the front line, there was no time to be brave. There was only time to scream. The telephone lines were cut in the first minute. Command bunkers were buried under tons of earth.

And then out of the smoke and the mist came the monsters. Tiger tanks, king tigers, 60tonon beasts of steel that were immune to American bazookas. They rolled out of the fog like prehistoric creatures, crushing jeeps and men beneath their tracks. Behind them came the whiteclad SS stormtroopers moving like ghosts in the snow, firing their machine guns from the hip. Chaos. Absolute total chaos.

The American line didn’t just bend, it evaporated. Units were surrounded before they even knew they were under attack. Men were fighting with shovels and empty rifles. By midday, thousands of American soldiers were surrendering. It was the largest mass surrender of US troops in the war against Germany.

Reports started flooding into the Allied headquarters in Paris, but they made no sense. Panic spread like a virus up the chain of command. A radio operator screamed into his microphone that heavy tanks were in the Arden. The commanders in the rear shouted back that it was impossible. They yelled that there were no tanks in the Arden.

The operator cried back that they were there and they were killing everyone. In the span of 6 hours, the Germans punched a hole 45 mi wide in the Allied front. They were pouring through the gap like water through a burst dam heading straight for the Muse River. If they crossed that river, they would split the British and American armies in two. They would capture the giant supply port of Antwerp.

They would starve the Allies of fuel. The war would be lost. At Supreme Headquarters, General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Supreme Commander, stared at the map. His face was pale. The red arrows were growing longer by the hour. His intelligence officers were stunned. They stuttered and made excuses about the weather and the radio silence.

But hundreds of miles away in the headquarters of the Third Army, there was no panic. There was no screaming. There was only the quiet scratching of a match lighting a cigar. Colonel Oscar Ko walked into General Patton’s office. He didn’t run. He didn’t look terrified. He looked vindicated.

He handed Patton the latest report and said calmly that it was happening exactly where they said it would. Patton didn’t look surprised. He looked at the map at the ghost army that was finally revealing itself. He growled that the bastards had stuck their head in the meat grinder and he had the handle. But having the handle and turning it were two different things.

Eisenhower called an emergency summit of all the top commanders at Verdun on December 19th. The atmosphere in the room was thick with cigarette smoke and fear. Everyone was there. General Bradley, Field Marshall Montgomery, the air was freezing because the heating had failed.

The generals stood around a pot-bellied stove, rubbing their hands, looking at the disaster unfolding on the map. Eisenhower looked at his commanders. He needed a miracle. He needed someone to stop the German tidal wave. But everyone in the room knew the physics of war. You cannot stop a blitzkrieg in motion. You cannot turn an army around in the snow. Eisenhower turned to Patton.

He asked him heavily how long it would take to turn his army around and attack the southern flank of the bulge. The other generals did the math in their heads. Patton’s army was currently fighting in the Sar region a 100 miles south. To attack the bulge, he would have to disengage from a fight, turn 130,000 vehicles around on icy roads, drive through a blizzard, and launch a coordinated attack against fresh panzer divisions. It would take a week, maybe 10 days.

By then, the Germans would be in Antworp. Patton stood up. He looked at Eisenhower. He didn’t blink. He shouted loudly that he could attack on the morning of December 22nd. The room went dead silent. A British officer let out a short, dry laugh. He muttered that Patton shouldn’t be a fool.

He said that was 48 hours away and it was a logistical impossibility to move a core that fast. Patton snapped back arrogantly that he wasn’t being a fool. He told them his staff had been working on this for days. He said he had three divisions ready to roll and the code name was Gabriel. He just needed to make the call. The other generals stared at him. They looked at him like he was a magician pulling a rabbit out of a hat.

They didn’t understand. They thought Patton was guessing. They didn’t know that Oscar Ko had already mapped every road. They didn’t know the fuel trucks were already idling. They didn’t know the orders were already typed, sitting in a safe, waiting for this exact moment. Eisenhower looked at Patton.

He saw the fire in his eyes. He said quietly to start the ball rolling. Patton walked out of the room. He found a telephone. He dialed his headquarters. He shouted the code words, “Playball, Gabriel.” And then the impossible happened. The Third Army didn’t just turn. It spun. Imagine a snake coiling back to strike.

In the middle of the worst winter Europe had seen in 30 years, the roads of France became a river of steel. It was a nightmare of logistics. Tanks slid on the ice and crashed into ravines. Trucks broke down and were pushed into ditches to keep the column moving. Men froze in the back of open carriers, their uniforms stiff with ice. But they didn’t stop. Patton was everywhere.

He stood at the crossroads in his open jeep, freezing wind whipping his face. He screamed at the drivers to move. He yelled that there were men dying up there and they didn’t dare stop. He knew that speed was the only thing that mattered. Every hour they wasted was another hour the Germans had to fortify their positions.

But while Patton was racing north, the Germans were closing the trap on the town of Baston. Baston was a small market town where seven roads met. It was the heart of the Ardens. Whoever controlled Baston controlled the entire battle and right now it was surrounded. Inside the town were the men of the 101st Airborne, the screaming eagles, paratroopers.

They were tough, but they were in a desperate situation. They were completely cut off from the outside world. They had no winter clothes. They were fighting in summer uniforms in subzero temperatures. They were digging foxholes in frozen ground that was as hard as granite. They had no medical supplies because their field hospital had been captured on the first day.

Inside the dark cellers of the town, the wounded men were screaming. The only thing the doctors could give them was a sip of cognac to dull the pain. They used torn bed sheets to wrap shattered legs. They ran out of bandages. They ran out of morphine. Surrounding them were four German divisions, four against one. The German commander, General Von Lutvitz, sent a message under a white flag.

It was a long formal letter demanding an immediate surrender to save the Americans from total annihilation. The American commander was General Anthony McAuliffe. He read the letter. He looked at his dirty, freezing staff officers. He laughed and said they had to be kidding. He typed out his official reply to the German army.

It wasn’t diplomatic. It wasn’t polite. It was one word typed in the center of the page. Nuts. The German officers were confused. They asked the American messenger what the word meant. The soldiers smiled and told them it meant they could go to hell. The Germans were furious. They unleashed everything they had on Baston. They bombed it from the air. They shelled it with heavy artillery.

They sent wave after wave of tanks against the perimeter. But the paratroopers didn’t break. They held the line. They fought with frozen fingers. They fought with stolen weapons. When they ran out of ammo, they fought with knives and shovels. They held on because they knew one thing. Patton was coming.

But Patton had a problem. Even he couldn’t scream at the weather. The fog was so thick you couldn’t see the hood of your jeep. The snow was knee deep. And the German Luftvafa, the air force everyone said was dead, was back. German planes swooped down on the columns, strafing the trucks and bombing the American positions. Patton needed clear skies.

He needed his air support. But the forecast was terrible. Snow, snow, and more snow. So Patton did something that became legend. He called his chaplain, Father O’Neal. He told the chaplain he wanted a prayer for good weather. The chaplain looked confused and asked if he wanted a prayer to kill Germans.

Patton barked that he wanted a prayer for sunshine because he was on good terms with the Lord and he needed help. They printed the prayer on small cards and gave one to every soldier in the Third Army. 250,000 men shivering in the snow reciting a prayer for sunlight. It sounded crazy. It sounded desperate.

But the next morning on December 23rd, the miracle happened. The snow stopped. The clouds broke. The sun came out. It was a cold, hard, brilliant sun. The American pilots scrambled to their planes, yelling that the old man had done it. Thunderbolts and Mustangs roared into the air, raining hell on the German tanks.

The sky turned black with smoke as the German armor burned. The Third Army surged forward. They were now crashing into the southern flank of the German bulge. The fighting was brutal. It was close quarters combat in the snow. Bayonets and grenades, but the Americans had the momentum. They could see the smoke rising from Bone in the distance.

They knew their brothers were dying inside that town. On Christmas Day, the fighting reached its peak. The Germans launched one final desperate attack to crush Baston. They sent flamethrower tanks to burn the paratroopers out of their holes. The snow turned red with blood, but the line held.

And on the afternoon of December 26th, Lieutenant Charles Bogus, commanding a Sherman tank named Cobra King, crested a hill south of the town. He had been fighting for 3 days straight without sleep. His eyes were red, his hands were shaking. He looked through his periscope. In the distance, about a thousand yards away, he saw a line of foxholes in the snow.

And inside those foxholes, he saw green helmets. He didn’t know if they were Germans or Americans. He ordered his gunner to aim the cannon. He moved the tank forward slowly. He shouted to his crew to keep their eyes open and blast them if they fired. The tank rolled closer. 50 yards, 40 yards. Suddenly, a figure stood up in one of the foxholes.

It was an American soldier. He didn’t raise a rifle. He didn’t run. He just stood there, staring at the white star painted on the side of the tank. Lieutenant Bogus opened the hatch. He climbed out. He walked through the snow toward the paratrooper. The paratrooper was shaking. He had tears freezing on his cheeks.

He reached out a dirty hand. Boggas took it. He smiled and said he bet the lieutenant was glad to see them. The siege was broken. The road was open. Ambulances raced into the town to save the wounded. Ammo trucks raced in to reload the guns. When the news reached headquarters, Patton didn’t cheer. He didn’t celebrate.

He just nodded. He knew that the impossible had been done. He had turned an army in the middle of a blizzard and defeated the best soldiers Germany had left. The Battle of the Bulge would continue for weeks. But the German gamble had failed. They had lost their tanks. They had lost their fuel.

And they had lost their last chance to win the war. It was one of the greatest military feats in history. A maneuver that is still studied in war colleges today. The speed, the precision, the audacity. But as the smoke cleared and the cameras arrived to film the victory, they focused on Patton. They focused on his speeches. They focused on the tanks.

Nobody took a picture of the quiet man in the back of the room. Nobody interviewed Colonel Oscar Caul. He simply went back to his desk in Nansi. The room was quiet again. The maps were still on the wall. Most men would have been out drinking champagne. Most men would have been bragging to the newspapers that they predicted the attack and saved the army.

But Oscar Caul wasn’t most men. He picked up his grease pencil. He looked at the map and he started marking the next threat. He knew that the war wasn’t over. He knew that thousands more would die before they reached Berlin. And he knew that his job wasn’t to be a hero. His job was to see the things that nobody else wanted to see.

Because the lesson of the Battle of the Bulge isn’t just about firepower. It isn’t just about tanks or air support. It is about the courage to listen. Patton was a great general, but he would have been a dead general if he had ignored the quiet voice in the corner. He would have been the general who lost the war. Instead, he became the general who saved it, not because he was the smartest man in the room, but because he was smart enough to trust the man who was.

Thousands of men came home from the Arden because of that trust. They grew old. They had families. They lived their lives. All because one man looked at a stack of boring reports and refused to look away from the truth. This brings us to the end of the battle, but not the end of the story. Because the tragedy of Oscar Caul wasn’t the war.

The tragedy was what happened after. When the peace treaties were signed and the parades were held, the world wanted heroes who looked like movie stars, they wanted loud men with ivory pistols. They didn’t want a quiet man with thick glasses who solved problems with math. So history did what history always does.

It remembered the noise and it forgot the signal. By January 1945, the guns in the Ardens finally fell silent. The snow began to melt, and as the white blanket washed away, it revealed the terrible cost of the arrogance that had ignored Oscar Cox’s warnings. 19,000 Americans lay dead. 47,000 were wounded. 23,000 were missing or captured. It was the costliest battle in the history of the United States Army.

The Germans fared even worse. They left 100,000 men and almost all of their tanks rusting in the mud. The gamble had failed. The road to Berlin was open. But as the Allied armies raced into Germany to end the Third Reich, the partnership that had saved the war began to dissolve. General Patton continued his drive across the Rine.

He was unstoppable. He captured thousands of towns. He liberated concentration camps. He rode on the back of his tank like a conquering king. The press couldn’t get enough of him. He was the face of victory. Oscar Caul, as always, remained in the shadows. He stayed in the briefing rooms. He kept counting the enemy units. He kept predicting the German moves. But the danger had passed.

The desperate need for a man who could see the future was gone. And then the war ended. May 1945. Germany surrendered. The guns stopped firing across Europe. The soldiers went home. Parades were thrown in New York and London. Confetti rained down on the heads of the generals. But fate has a cruel sense of humor.

George Patton, the man who had survived gunshot wounds in World War I, the man who had walked through artillery fire without flinching, the man who believed he was immortal, did not die on the battlefield. In December 1945, just months after the victory, Patton was involved in a minor car accident in Germany. His staff car collided with a truck at low speed. Everyone else in the car was fine, but Patton broke his neck.

He lay in a hospital bed for 12 days, paralyzed. The man of action was trapped in a broken body. He whispered to his wife, “This is a hell of a way to die.” And then he was gone. The lion was dead. The legend was cemented forever. He was buried in Luxembourg at the head of his troops who died in the Battle of the Bulge.

Even in death, he was leading his men. But what about the ghost? Oscar Ko survived the war. He returned to the United States. But there were no parades for him. There were no movies made about his life. There were no statues erected in his hometown. He was a quiet professional in a world that loved loud heroes. He retired from the army and moved to a small house.

He lived a simple life. He watched as the history books were written and he watched as his name was left out of them. Historians wrote about the intelligence failure of the Battle of the Bulge. They wrote that the Allies were completely surprised. They wrote that nobody saw it coming. Ko read these books.

He knew they were wrong. He knew that he had seen it coming. He knew that the files existed. He knew that the warnings had been given. But he didn’t scream. He didn’t go to the newspapers and demand a correction. He didn’t fight for his legacy. He simply sat down, pulled out his typewriter, and wrote his own account.

He called it G2, Intelligence for Patent. It wasn’t a bestseller. It was a dry, technical book. It was filled with maps and reports. It was a textbook for intelligence officers, not a thriller for the public. In the book, he didn’t brag. He simply laid out the facts. He showed how the clues were there.

He showed how the patterns were clear, and he showed how one general had the courage to listen. Ko died in 1970. He passed away quietly just as he had lived. And for a long time that seemed to be the end of the story. Patton was the hero. Ko was the footnote. But truth has a way of surviving. Decades later, military historians began to dig deeper into the archives. They opened the old files from the Third Army.

They looked at the daily briefing notes from November 1944, and they were shocked. They found Ko’s warnings. They found the maps with the big red question marks over the Arden. They found the predictions that were accurate down to the day and the mile. They realized that the Battle of the Bulge wasn’t an intelligence failure. It was a listening failure.

The intelligence was perfect. The system worked. The only thing that broke was the human element at the top. the arrogance of the commanders who refused to believe the data because it didn’t fit their happy narrative. Today, inside the US Army Intelligence Hall of Fame, there is a place for Oscar Ko.

He is studied by young officers as the gold standard of what an intelligence officer should be. He is the patron saint of the truth tellers. But his story is about more than just military tactics. It is a mirror for all of us. We live in a noisy world. We are surrounded by people who are shouting. Politicians, influencers, bosses.

Everyone is trying to be the loudest person in the room. Everyone wants to be Patton. We reward confidence. We reward charisma. We follow the people who say, “I know the way.” without hesitation. But often the people who really know the way are the ones whispering. Think about your own life. Think about your business, your family, your relationships.

Who is the Oscar in your circle? Maybe it is the quiet employee who sends you an email saying, “I think there is a problem with these numbers and you ignore it because business is good. Maybe it is your wife or your husband sitting you down and saying, “I think we are drifting apart.” and you brush it off because you are busy.

Maybe it is a friend who pulls you aside and says, “I think you are drinking too much.” And you laugh it off because you are having fun. We all have a ghost in our lives. Someone who sees the train wreck coming before we do. Someone who loves us enough to tell us the uncomfortable truth. The tragedy of the Battle of the Bulge wasn’t that the Germans attacked.

That is what enemies do. The tragedy was that thousands of men died because the leaders were deaf to the warning. Don’t let that be your tragedy. When the quiet voice speaks, stop. Turn down the noise. Put away your ego and listen. Because the loud people will tell you what you want to hear. They will tell you that you are winning.

They will tell you that the war is over and you will be home by Christmas. But the quiet people, the ghosts, they will tell you what you need to hear. They will tell you where the tigers are hiding. And they might just save your life. This channel is dedicated to finding those ghosts. We are dedicated to digging up the stories that history tried to bury.

We believe that the missing pages are the most important ones. If you believe that the truth matters, no matter how quiet it is, then join us. Click that subscribe button, turn on the notifications, help us tell the stories of the men and women who stood in the shadows and changed the world. There are thousands of files left to open. There are thousands of voices waiting to be heard.

My name is James and this has been WW War Missing Pages. I’ll see you in the next briefing.

News

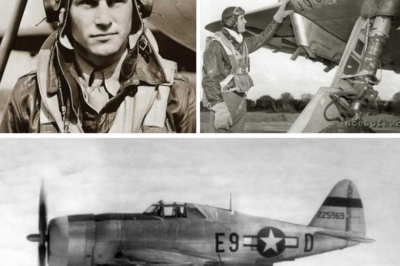

CH2 The Unbelievable Survival of Lieutenant Robert S. Johnson – How One P-47 Thunderbolt Defied 200 Bullets and Forced a German Ace to Kneel

The Unbelievable Survival of Lieutenant Robert S. Johnson – How One P-47 Thunderbolt Defied 200 Bullets and Forced a German Ace…

CH2 THE FARMER’S TRAP THAT SHOCKED THE THIRD REICH: How One ‘Stupid Idea’ Annihilated Two Panzers in Eleven Seconds and Changed Anti-Tank Warfare

THE FARMER’S TRAP THAT SHOCKED THE THIRD REICH: How One ‘Stupid Idea’ Annihilated Two Panzers in Eleven Seconds and Changed…

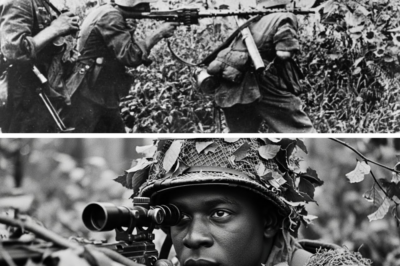

CH2 THE SIX AGAINST EIGHT HUNDRED: The Guadalcanal Miracle That Even Japan Called ‘Witchcraft’ — How a Handful of Black Marines Turned a Jungle Death Trap into the Most Mysterious Stand of the Pacific War

THE SIX AGAINST EIGHT HUNDRED: The Guadalcanal Miracle That Even Japan Called ‘Witchcraft’ — How a Handful of Black Marines…

CH2 THE INVISIBLE GHOST OF NORMANDY: How One Black Sharpshooter’s Ancient Camouflage Turned Him Into the Wehrmacht’s Worst Nightmare – Germans Never Imagined One Black Sniper’s Camouflage Method Would K.i.l.l 500 of Their Soldiers

THE INVISIBLE GHOST OF NORMANDY: How One Black Sharpshooter’s Ancient Camouflage Turned Him Into the Wehrmacht’s Worst Nightmare – Germans…

CH2 THE PLANE THEY CALLED USELESS — The ‘Flying Coffin’ That HUMILIATED Japan’s Zero and TURNED the Pacific War UPSIDE DOWN

The Forgotten Fighter That Outclassed the Zero — The Slow Plane That Won the Pacific” January 1942. The Pacific…

CH2 ‘JUST A PIECE OF WIRE’ — The ILLEGAL Field Hack That Turned America’s P-38 LIGHTNING Into the Zero’s WORST NIGHTMARE and Changed the Pacific War Forever

‘JUST A PIECE OF WIRE’ — The ILLEGAL Field Hack That Turned America’s P-38 LIGHTNING Into the Zero’s WORST NIGHTMARE…

End of content

No more pages to load